Abstract

Background: Tobacco companies target young adults through marketing strategies that use bars and nightclubs to promote smoking. As restrictions increasingly limit promotions, music marketing has become an important vehicle for tobacco companies to shape brand image, generate brand recognition and promote tobacco. Methods: Analysis of previously secret tobacco industry documents from British American Tobacco, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Results: In 1995, British American Tobacco (BAT) initiated a partnership with London’s Ministry of Sound (MOS) nightclub to promote Lucky Strike cigarettes to establish relevance and credibility among young adults in the UK. In 1997, BAT extended their MOS partnership to China and Taiwan to promote State Express 555. BAT sought to transfer values associated with the MOS lifestyle brand to its cigarettes. The BAT/MOS partnership illustrates the broad appeal of international brands across different regions of the world. Conclusion: Transnational tobacco companies like BAT are not only striving to stay contemporary with young adults through culturally relevant activities such as those provided by MOS but they are also looking to export their strategies to regions across the world. Partnerships like this BAT/MOS one skirt marketing restrictions recommended by the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. The global scope and success of the MOS program emphasizes the challenge for national regulations to restrict such promotions.

Keywords: China, club promotion, dance music, London, Lucky Strike, marketing, Ministry of Sound, State Express 555, Taiwan, tobacco, young adults

Introduction

Tobacco companies target young adults (aged 18–24 years) through marketing strategies that use the social environment to promote and solidify smoking.1–3 Bars and nightclubs are ideal venues for promotions that seek to integrate smoking with ‘normal adult life’ since they are frequented by young adults where tobacco and alcohol are consumed legally and socially reinforced.1,4–6 Most young people start experimenting with smoking before they are 18 years old and tobacco companies are interested in the first brand they try. Targeting 18- to 24-year-olds is the best way to target teens because 18- to 24-year olds are their role models. Promotions in adult-only venues (i.e. bars and nightclubs) have become even more important in the context of increased regulation, such as the prohibition on youth targeting in the USA following the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) that settled litigation brought by state Attorney General against the tobacco industry.7 Moreover, companies can access influential social leaders in the bar/club environment.2,8

Bar and nightclub promotions began in the mid-1980s when Reynolds used ‘field marketing’ strategies that employed social interaction and consumer involvement.4 Their Camel ‘Smooth Moves’ campaign involved live music, contests, games and free cigarette samples.4 In the 1990s, bars, clubs, discos and karaoke bars increasingly became fertile ground for cigarette promotions and events aimed at young adults as reflected in increased event advertisements in the young-adult-focused alternative press.2,4–6 Such activities continued into the 21st century, such as RJ Reynolds’ Camel Speakeasy Tour in 2004, which invited trendsetting young adults to events with music DJs.9

Music marketing has been a powerful vehicle for tobacco companies to shape brand image, generate brand recognition and promote cigarettes to young adults.6 Brown and Williamson’s (B&W) sponsorship of the Kool Jazz Festival in 1975 in New York leveraged the company’s belief that ‘music is the framework or building block for a deep, emotionally resonating theme … [with dimensions of] nostalgia, reflection of mood, [and] group identification to attract young African American males to menthol cigarettes’.10 This music marketing plan was integrated with club events, touring music vans, and free samples—all with the aim of ‘delivering a consistent message across promotional platforms’ while skirting advertising restrictions.6 In 1991, British American Tobacco (BAT) research recognized that music had a ‘universal appeal’ and ‘youthful imagery’ that could ‘readily be tailored to suit specific markets and musical tastes’.11 BAT and Philip Morris (PM) also sponsored the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festivals in the 1980s and 1990s for Barclay and Marlboro.12–14 BAT commissioned news agency Reuters to prepare a TV news report on the festival and distribute it to broadcasters across Europe. This report resulted in ‘15 separate items of Barclay branding’ shown on MTV, a TV channel with an almost exclusive young audience.15

Just as B&W used jazz music to launch an integrated US marketing campaign in the 1980s, BAT exploited the popularity of dance music among young adults in Britain in the mid-1990s. Dance music significantly impacted 1990s British youth culture since its 1980s emergence underground as an ‘ideal accompaniment’ to recreational drugs like Ecstasy that were part of ‘play, enjoyment, and entertainment’ integral to youth activities.16 Dance music promoted club-going, especially among those aged 15–24 of whom 38% went clubbing at least once a week in 1996.17 Among the club scene in the 1990s, the Ministry of Sound (MOS), a London dance club, rose to ‘superclub’ status and its prominent ‘pop star brand name’ caught BAT’s attention in BAT’s campaign to promote its Lucky Strike brand.17

MOS began in 1991 as an underground London nightclub that ultimately became a major European brand centered on dance music that is a ‘major lifestyle factor’ for young adults around the world.18 Through their music/dance club independent record label and branded merchandise, MOS was considered by major transnational companies in several industries to be well versed in young adult culture and the market young adults presented.18 By establishing an association with MOS, BAT forged a relationship between young adults and its Lucky Strikes brand in London and, later, its 555 brand in Asian cities. In making such partnerships, BAT sought to capitalize on the willingness of young adults to follow and adopt trends.

Methods

We searched the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://www.legacy.library.ucsf.edu) between June 2007 and January 2010 beginning with ‘Ministry of Sound’, ‘MOS’, ‘Dance Music’ and ‘Music Sponsorship’. Names of people and specific venues from relevant documents were subsequently searched using the snowball technique.19 The searches resulted in approximately 100 documents that were relevant to this paper.

Results

Pairing tobacco advertising with music events: basis for the partnership

In 1995, BAT re-launched Lucky Strike King Size Filter Tipped and launched Lucky Strike Lights to compete with PM’s Marlboro and Marlboro Lights in the UK.20 Lucky Strike was to be an ‘international brand with a distinctive American personality’ targeting men and women aged 18–24 who are trend-conscious and have ‘aspirational’ lifestyles.20 Specific target groups consisted of male ‘Young Affluent Urban Smokers (YAUS)’, ‘current Marlboro and Marlboro Lights smokers and other [US International Brand] Smokers’ and ‘College/University students’.21 BAT introduced Lucky Strike in London and noted that American culture was perceived as ‘fashionable and aspirational’ there.20 Ultimately, BAT’s strategy was to ‘make Lucky Strike fashionable/credible and cutting edge/the cigarette to be seen with’.20

BAT faced a few challenges launching Lucky Strike. With limited time to plan,20 UK tobacco marketing restrictions22 and a limited budget,22 BAT and its marketing firms chose to advertise Lucky Strike through mostly non-traditional media with only tactical traditional mass media support of events.22 Ultimately, Lucky Strike launched in August 1995 in central London with Lucky Strike ‘ “crew”23 or “posse” ’21 sampling at venues ‘snug[ly] integrat[ed]’20 with the magazine content featuring these venues in Time Out magazine, the London entertainment weekly24 events listing magazine.25,26 The sampling teams were at listed events ‘prearranged’ by BAT.25 The Lucky Strike ‘ “hit-squad” posse’21 was to ‘take Lucky Strike into the heart of the trend setters territory (particularly in pubs and clubs) placing the brand where it will gain credibility by association with the venue and clientele’.21

BAT sponsored venue events not only due to budget constraints but also because events positioned Lucky Strike as a ‘ “good time” brand with American heritage’ particularly ‘appropriate to UK YAUS’ and gave the marketing team ‘greater creative flexibility within strict UK voluntary Agreement codes of practise’.22 BAT was aware that other tobacco companies were focusing advertising strategies on retail stores and hotels, restaurants and catering (HORECA) venues in response to increasing marketing restrictions.24 Moreover, BAT knew that young adult trends were created in HORECA venues, considerable amount of time is spent in HORECA, smoking is accepted in HORECA and marketers can specifically target promotions in HORECA.27 In 1996, BAT HORECA global channel development manager Ron Reinders proposed, ‘If we liaise closely with [discos and bars] and develop a partnership for the promotion of the outlet and our brands, then we should be able to gain control of the music, light show and DJ for the purposes of BAT promotions’.27 BAT’s advertising firm One Four One suggested using MOS in BAT’s HORECA branding plans following MOS’s existing ‘brand support’ for brands like Absolut Vodka and Sony Playstation.28 As Reinders said, ‘The [MOS] is recognised around the globe as the most trendsetting dance music phenomenon. Our objective is to reach adult consumers in the “hottest” venues everywhere and dance music is now captivating ASU30 [adult smokers under 30] audiences around the world’.29

Lucky strike/MOS partnership: UK implementation

According to BAT internal reports in the mid-late 1990s, MOS was recognized for ‘putting dance music on the map’29 as a ‘youth phenomenon’30 and as the world’s largest merchandizing company for dance music,30 winning ‘Best Club’ at the International Dance Awards in 1995 and 1996.30 MOS’s high profile global status attracted, among others, young, urban, trendy clientele; a partnership seen as offering BAT ‘direct access to a crucial target audience, the ASU30 segment’.29

BAT-sponsored two31 ‘Lucky Strike/Ministry of Sound Tours’25 in 1996, followed an exclusive worldwide deal.29 The first Lucky Strike/MOS event launched in October 1995 was followed by fours of Lucky Strike/MOS events in >50 London pubs, clubs and student unions (figure 1).23 These events were supported with cigarette sampling, merchandise giveaways and advertisements in Time Out.23 BAT continued Lucky Strike’s partnership with MOS in 1996,22,25 hosting a student union tour, including 10 additional nights of events in universities and college campuses in London and South East England22,25,32 (figure 2). BAT saw the MOS tour as the answer to anticipated consumers’ questions, ‘ “What’s in it for me?”…“Why should I switch brands?” ’25 BAT thought the ‘chance [for young adults] to go to the biggest, trendiest night club in England for free with Lucky Strikes’ should be a reason enough to buy Lucky Strikes.25 Lucky Strikes’ ‘sampling posse’ brought Lucky Strike cigarettes to the London student union events33 while MOS brought their DJs and equipment to the party. BAT also required venues to sell Lucky Strikes exclusively during BAT-sponsored events34 and stock their vending machines with Lucky Strikes as a means of ‘securing distribution after the event’.25

Figure 1.

Promotional image used by BAT and MOS to promote their Lucky Strike Tour.30,31,76 These images with the Lucky Strike bulls-eye and the M\cephastorage2OS logo on juxtaposed turn-tables with ‘Lucky Strike Presents the Ministry of Sound Tour’ were used to promote co-branding. This image was likely used on a London ‘cardguide “interactive” postcard promotion [that] hit over 200 London bars and clubs’ where these postcards were free giveaways.31 (The London cardguide was a ‘network of high quality postcard display units in café/bars in central London used by advertisers’.25) Lucky Strike’s cards ‘were taken before those of any other advertiser. 228 000 cards [were] taken from [venues]—all of which cater for the 18–30 age group’.25 In 1995, BAT and MOS established their Club Tour, which included a 4-week foray into London pubs and university student unions, with promotional materials and merchandise, product sampling. The tour started with two nights at the MOS on 28 and 29 October 199523, followed by events at over 50 clubs and pubs, including student unions at London universities.25 Free samples of Lucky Strike and branded materials were distributed25

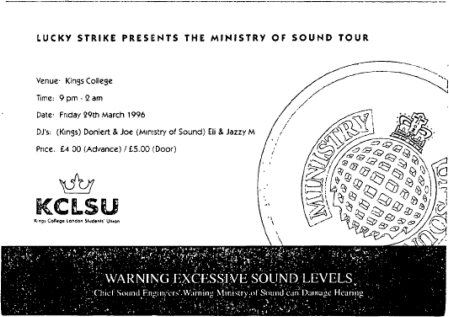

Figure 2.

Flyer used to promote a BAT/MOS Tour held on 29 March 1996 at Kings College in London.77 After the initial Lucky Strike/MOS event in 1995,23 a follow-up tour was planned at various universities around London in conjunction with student unions,32 including Kings College. Each of the 10 additional Student Union tour dates was complete with sampling and games with branded gifts25

The popularity of the Lucky Strike/MOS Tour evidenced by the ticket sales and requests for repeat visits surpassed BAT’s expectations.25 By the end of the 10-date tour in June 1996, the tour had attracted over 7000 attendees at university campuses.32

MOS Lucky Strike partnership: going global with State Express 555 in Asia

In 1997, BAT expanded its MOS association to Asia with an international program and tour which recreated its successful London Lucky Strike/MOS partnership to promote State Express 555 (555) to trendsetting young adults.18,35 BAT launched Project Enterprise in 1997, a 555 market research plan and analysis of cultural/social insights into consumer (notably ASU30) motivations, especially in the HORECA channel.36,37 Project Enterprise revealed a gap between the ‘current brand world’, the product and consumers. BAT’s vision for 555 was to be ‘Asia’s number one premium IB [international brand] with a core franchise of young professionals’,36 and their aspirants36 whom BAT would win through a HORECA strategy including nightclubs.

BAT strategy documents from 1998 reveal that ‘all [555] markets agreed that dance music in its broadest sense is right for 555 … as it represents the international language of ASU30’.37 Given the consensus to use dance music, BAT identified MOS as an ‘expert partner’37 for its Asian HORECA strategy to ‘make the 555 Brand World more relevant to ASU30’.36 Bringing the MOS campaign to Asia mutually reinforced regional and global strategies.38

In 1997, BAT sponsored a well-developed, highly targeted 555/MOS pilot program36 with an integral MOS tour exclusively in China and Taiwan, marketing support materials and public relations35 ‘aimed at trend setters/early adopters’.36,39 As in the UK, the tour comprised a set of live nightclub performances by MOS DJs in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Shanghai (which appears to have been replaced by Shenzhen35,40) and Taipei in October 1997.35,40 MOS contracted with BAT to build tour sets35 which BAT hoped would create a customized ‘brand world’ for each event ‘to provide a distinctive clubbing environment’29 along with placing logos in video screens and cigarette sampling.39

The 555/MOS tour encompassed metropolitan areas in China and Taiwan and planned smaller-scale launches in Cambodia,41 Vietnam18 and Bangladesh18 as well as non-tour promotions in Mauritius, Indonesia and Laos.35 MOS agreed to produce 555/MOS-branded giveaways for target consumers in all these regions, including Club Culture Guides (brochures), 3-track CDs (figure 3) and branded merchandise (jackets, T-shirts, baseball caps and record bags) while executing public relations activities and distributing flyers and posters.35 All support material featured the key 555/MOS logo (figure 4).35 To sustain brand awareness, BAT enlisted MOS to record and produce ‘CD Sessions’, MOS promotional CDs for local DJs to play in venues and a ‘DJ Session’ for radio.35 Ultimately, BAT paid MOS more than £337 000 for the 1997 555/MOS program in Asia.35

Figure 3.

An example of the 3-track CD giveaway to consumers at venues as part of the 555 MOS program in 1997.35 Dance music was an integral part of the 555/MOS Tour. Tour promotions were supplemented by these CD samplers as well as ‘CD Sessions’, three 1-h MOS CDs playing in HORECA outlets by local DJs to promote 555 and ‘Radio Sessions’, which were recorded radio DJ sessions for local stations.35 BAT paid MOS to make this CD sampler as giveaway as well as Club Culture Guides (brochures) and branded jackets, T-shirts, baseball caps and record bags, all of which featured the 555/MOS key logo and intended as giveaways (see figure 4 for logo)35

Figure 4.

The key logo for BAT’s State Express 555 1997 MOS World Tour in Asia.35 The creation of support materials involved exchange of royalty-free licenses between MOS and BAT’s 555 for use of respective trademarks in China and Taiwan.35 In logos and creative material like this one, BAT aimed for an ‘integrated 555/MOS look’, which was subtle and purposefully not ‘in your face’18

Evidence of effectiveness

In June 1996, BAT’s managers received reports of increased sales of both Lucky Regulars and Lights after each Lucky Strike/MOS Tour event.32 An internal draft of a Lucky Strike UK press release announced, ‘With sales up over 100% (June 1996—year on year), Lucky Strike has successfully completed a link up with top London night-club [sic], The Ministry of Sound’.32 Lucky Strike’s doubling of sales in the context of a declining UK cigarette market in the early 1990s42 was encouraging news, supporting continuing music/club tours to grow Lucky Strike and other BAT brands.32 Managers also reported that the MOS tour43 successfully achieved ‘incremental traffic flow to [retail] outlets from [the] target ASU30 group’ after the MOS tour in Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Taiwan.40

BAT reported in 1998 that their ‘niche marketing approach’ using MOS was particularly appropriate for reaching ASU30 and was cost-effective.18 The original Lucky Strike/MOS partnership was driven by BAT’s awareness that ‘if people are enjoying what a brand “brings” them they will usually accept that brand’.22 Thus, whereas earlier BAT campaigns relied on the cigarette brand itself as the major vehicle for promotion,6 the partnership with MOS took advantage of ‘brand stretching’ and name association with another brand name, relying on the MOS name to attract ASU30 to its brands. As with its Lucky Strike/MOS plan, BAT aimed to create ‘positive associations’ for 555 by linking it to dance music/club culture that MOS represented; BAT thought this MOS partnership could be ‘an effective way of initiating a relevant dialogue with this highly influential group of smokers’ whereby ‘555 has benefited from [MOS’s] strong brand equity which has reinforced [555’s] own brand values.18

The success of the MOS program and tour in London, China and Taiwan stood as a model for BAT’s international managers who extended the MOS tour’s reach to the Czech Republic,44 Venezuela,45 Brazil,46 Hungary,47 Mauritius48 and South Africa49 in the late 1990s for marketing Lucky Strike, 555 or Benson and Hedges cigarettes. The global marketing deal between BAT and MOS in 1998 involved Lucky Strike promotion in Russia and Western Europe as well.50 In 1998 in Prague, Lucky Strike club parties connected to MOS London clubs through live audio and video transmissions.44 Also in 1998, managers from BAT UK recommended that BAT Hungary consider a MOS deal within its HORECA strategy since UK managers felt MOS ‘joint ventures’ and similar partnerships added much value to BAT’s market position.47 In 1999, Venezuela considered staging the ‘successful and often repeated LS [Lucky Strike/MOS] club event’ as a ‘Back to School’ party45 and Brazil’s Lucky Strike team considered including MOS in its ASU30 campaign.46 (We do not know if these plans were implemented.) BAT also launched Benson and Hedges in Mauritius in 1998 through a big musical event and its management team set aside 1.5 million MUR in 1999 for a MOS tour and radio sponsorship of MOS to target ASU30 ROCAS (Responsible, Optimistic, Confident and Ambitious Smokers).48 BAT wanted to bring the MOS to South Africa to promote Benson and Hedges because BAT believed MOS was ‘relevant’ to its market—particularly because MOS presented a ‘synergy of the Dance [sic] culture with SA [South African] trend-setters and developed market’ and presented ‘HORECA exploitation opportunities’.49 The MOS global partnership was so successful that in 1999 BAT UK contacted B&W about a possible MOS tour in the United States.51 B&W felt MOS did not have enough relevance in the US market and noted, incorrectly, that the US MSA restricted tobacco exploitation of ‘Adult-Only-Facility activities’.51

Other tobacco companies have worked with MOS and sponsored club parties around the world. Rothmans supported MOS events in Nigeria.39 RJ Reynolds sponsored a 1994 Camel/Kingston University School of Three Dimensional Design’s Degree Show held at the MOS, hosted a touring 1997 Camel party in Miami featuring the MOS and executed a Camel/MOS event in Argentina in 1999.52–54 PM also sponsored an elaborate travelling disco in Russia where at one event in Novosibirsk, Siberia, partygoers could only gain entry to the club by bringing five empty Marlboro packs.55 In 2008 PM International/Sampoerna sponsored US singer Alicia Keys’ concert in Jakarta, Indonesia, until Keys demanded PM’s withdrawal.56 Additionally in 2008, PM International associated itself with a reunion concert by Filipino band, Eraserheads.56 In 2009, Japan Tobacco International’s (JTI) Tanzania Cigarette Company has sponsored an event in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, called ‘STR8 Muzic Festival’ and BAT was still hosting DJs in its Lucky Strike LCrew Club Fumadores (Smokers’ Club) in Barcelona and other LCrew clubs throughout Spain.57–60

Discussion

Sponsorship and associations with music events and nightclubs is an industry-wide strategy to leverage music and clubs for cigarette branding. BAT’s partnership with MOS was part of a global effort to promote its cigarettes to trendy young affluent urban smokers by leveraging popular cultural trends in dance music and bar/club venues. BAT relied on the connection between young adults and popular music to facilitate a focused marketing campaign with the potential for international appeal.6,61 Even though local cultures were different, the BAT country teams all wanted to co-opt MOS to target the same ASU30 group.41,44–46,48 Like PM, BAT understood that young adults have similar psychographics across the world61 and thus could and should use similar marketing messages across regional markets.

In 1996, BAT planned a ‘YAUS Project’ with the aim of developing consumer insight into global youth trends, whose steering group included James Palumbo, MOS’s founder.62 This project had the same objectives as BAT’s 1997 Project Common Ground (PCG) study to develop a ‘consistent strategic platform for a redefinition of the Lucky Strike Strategic Platform including the positioning and the copy strategy’ and insight into ‘trendsetting consumers in [local markets and] the role of HORECA in their lives’.63 In 1998, PCG identified ‘global impact themes’64 for ASU30 that were integral to a ‘common understanding globally’ of the copy strategy and brand positioning for Lucky Strike, which ultimately transformed marketing campaigns across global regions to converge around this positioning based on issues faced by young adults around the world.65

The global partnership with MOS is an example of BAT’s ‘below-the-line’ 45,46,66,67 marketing strategies that serve as ‘an important driver for brand awareness’68 and skirt tobacco advertising restrictions that limit ‘above-the-line’ advertising in traditional media like TV, movies, radio and print. In 1996, BAT advised that ‘HORECA programs should concentrate specifically on attacking the YAUS segment’ for Lucky Strike.68 In the same year, BAT instigated Project Ozone, which resulted in a database of BTL [below-the-line] activities (including HORECA activities) for Lucky Strike as a ‘means of sharing information [across markets] on a regular basis’ to maintain consistency in marketing messages and build a ‘truly global brand’.69

By hiring MOS to carry out the tour and related marketing, BAT was able to co-opt MOS’s non-traditional marketing techniques, including MOS’s guerilla street marketing techniques aimed at trendsetting adult smokers, such as pre-tour bulletins on satellite television, features in young adult publications, blocking street traffic for public relations and filming ‘club style’ dance videos.18,43 Such promotions generate word-of-mouth and ‘produce a constant flow of commercial “propaganda” ’.70,71 While BAT was proud of the fruits of its MOS partnership,18,25,43,70 it noted that sponsoring dance music events ‘doesn’t fully associate [555] with Dance Music which is a much bigger and powerful idea than a couple of events’.70 In MOS plans for 1998, BAT noted, ‘activities aimed at establishing link with Dance music [sic] [are] under development … This covers more than just MOS & Music (e.g. Fashion)’.70 This statement situates the MOS partnership as one element within BAT’s understanding of the range of marketing mechanisms available to achieve ‘positive associations’ and ultimately more cigarette sales among young adults.

The partnership between BAT and MOS is significant not only because it is another example of the tobacco industry’s effort to influence behaviour but also because of the potential effect this marketing has on those younger than age 18. BAT knew they could reach youth through nightclubs; BAT had an extensive 1996 youth market research study revealing that teens aged 15–17 over-index in a consumer group that ‘just[s] wanna have fun’ known to frequent the MOS.72 Youth often choose brands they see as representative of their identity and use brands as means to portray that identity to peers.73 Partnerships involving cultural icons perpetuate the connection between cigarettes and relevant modern identities for youth.73 While the nominal target demographic of the BAT/MOS partnership was young adults, the desire of youth to emulate trendy young adults allowed the partnership to transcend young adults and influence future buying patterns across the UK, Asia and other global markets.

By using music as the language to shape brand image, BAT, PM and JTI, the industry’s three largest companies, continued their persistent marketing to vulnerable groups,39,52–55 with a likelihood that the social network between young adults and youth will transmit the brand images to youth. The WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control74 (FCTC) requires ratifying nations to end tobacco advertising, promotions and sponsorships. FCTC Article 13 prohibits brand stretching and brand sharing, such as the association between BAT and MOS.75 Limited experience with the MSA in the USA indicates that with vigilant enforcement, cross-promotions with young adult cultural institutions can be blunted.9 Those charged with drafting legislation in countries seeking to implement FCTC guidelines must recognize that bans on innovative non-traditional marketing are necessary to stop the association between culturally relevant behaviour and tobacco use. Such comprehensiveness is necessary to ensure that the FCTC’s advertising restrictions protect young adults as well as youth. The challenge in the future will be for countries to enact specific legislation to prohibit such cross-promotions and ultimately vigorously enforce these laws to prevent co-sponsorship and promotion of events.

Funding

National Cancer Institute Grant CA-87472. The funder played no role in conduct of research or preparation of the paper.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points.

British American Tobacco linked the Ministry of Sound nightclub with its Lucky Strike and State Express 555 brands in London, Guangdong, Shenzhen and Taipei during the 1990s, relying on the ‘universal language of dance music’ to establish brand relevancy among young adults and influence smoking behaviours in the face of increased marketing restrictions.

BAT’s relationship with London’s Ministry of Sound exemplifies the tobacco industry’s continued success in leveraging popular culture and trendy affiliated brands to influence young adults and manipulate patterns in smoking behaviour.

The exportation of this marketing strategy from London to Guangdong, Shenzhen and Taipei is an example of a transnational tobacco company building its global brands by applying standardized marketing principles.

The partnership between BAT and club and music culture highlights the importance of restricting future tobacco marketing campaigns and preventing the exploitation of music to promote tobacco products, as stated in the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Elena O. Lingas and Daniel K. Cortese for their comments on the drafts, Javier Toledo for providing information on tobacco activities in Spain and Reviewer 2 for his or her exceptionally careful and detailed review.

References

- 1.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:908–16. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biener L, Albers A. Young adults: vulnerable new targets of tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:326–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird S, Tapp A. Social marketing and the meaning of cool. Social Market Q. 2008;14:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:414–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sepe E, Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: targeting young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:75–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tob Control. 2006;15:359–66. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Givel M, Glantz SA. The ‘Global Settlement’ with the tobacco industry: 6 years later. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:218–24. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz SK, Lavack AM. Tobacco related bar promotions: insights from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11:i92–i101. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendlin Y, Anderson S, Glantz S. ‘Acceptable Rebellion’: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell camel cigarettes. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032599. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anon. Brown & Williamson; 1981. Kool Music Property. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tyu63f00. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ARD. British American Tobacco; 1991. May, International UK Brands: IBM Sponsorship Review—Benson & Hedges and 555. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yme08a99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banas T. Brown & Williamson; [16 August 1984]. Letter from T.P. Banas to R. McCabe regarding B&W cigarette sampling at Montreux Detroit Jazz Festival. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/don81d00. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barclay: 1994 Brand Plan, BAT (Suisse) SA. 10 October 1993. British American Tobacco. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gxh40a99.

- 14.Anon. Philip Morris; 1988. Switzerland—1987 Objectives Marketing. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kmv39e00 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuters Television. British American Tobacco; Reuters Television Distribution Report: Montreux Jazz Festival—7 to 22 July 1995. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fok90a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellars A. The influence of dance music on the UK youth tourism market. Tourism Manage. 1998;19:611–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCann P. British American Tobacco; [2 August 1996]. Dance Clubs Wake up to Power of Branding. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jom04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holroyd K, Ivatts S. British American Tobacco; 1998. Jan, ‘555 Ministry of Sound’ in Marketing Excellence. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yjl55a99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:267–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye B. British American Tobacco; [16 August 1995]. Letter from Beverley Kaye to Harriet Bryan regarding opportunity for Lucky Strike. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/okr14a99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delany JG. British American Tobacco; [3 August 1995]. UK Domestic Market, Lucky Strike. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pkr14a99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.One Four One Limited. British American Tobacco; 1996. Lucky Strike Autumn 1996 Proposals. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xgz63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barclay S. British American Tobacco; [16 October 1995]. Lucky Strike UK. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ijr14a99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.One Four One Limited. British American Tobacco; [25 July 1996]. Lucky Strike London Launch. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bky63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.BAT Marketing Department (Editor Kate Holroyd) British American Tobacco; 1996. Jul, ‘Getting Lucky in London’ in Marketing Excellence. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fzh73a99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.TimeOut Group. RJ Reynolds; TimeOut Group 2000–2001. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yto20d00. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinders R. British American Tobacco; [19 August 1996]. Proposed ‘Number One in Horeca’ Strategy. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qjh81a99. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gouldstone B. British American Tobacco; [29 July 1996]. Horeca Branding. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vne70a99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.British American Tobacco. British American Tobacco; 1998. Link: Merger Communications for the Employees of British American Tobacco and Rothmans International. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rao93a99. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lucky Strike Presents the Ministry of Sound Tour. No Date. British American Tobacco. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sey63a99.

- 31.Goddard L. British American Tobacco; [3 June 1997]. Lucky Strike Press Releases. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lxz44a99. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barclay S . British American Tobacco; [28 June 1996]. Lucky Strike—UK Domestic. Revised Press Release for David Bacon. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qaa54a99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anon. British American Tobacco; [2 August 1996]. Lucky Strike Party. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/grq72a99. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tobacco Merchants Association Inc. RJ Reynolds; [17 February 2000]. World Alert. WA 00-07. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hki65a00. [Google Scholar]

- 35.British American Tobacco Co. Ltd. and Ministry of Sound Tours Limited. British American Tobacco; [22 August 1997]. Agreement for the ‘555 Ministry of Sound Programme 1997’. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/twk82a99. [Google Scholar]

- 36.British American Tobacco Co. Ltd. British American Tobacco; 1997. Jun, State Express 555: 1998 Brand Guidelines. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eyp04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anon. British American Tobacco; [30 March 1998]. 1998—555 Strategic Review Meeting: Minutes/Agreed Actions. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/byp04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bain United Kingdom Inc. British American Tobacco; [19 Dec 1995]. BAT Industries: Consumer Classification Matrix. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tvm04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tobacco Control. China: rave paves way to grave. Tob Control 1998;7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.British American Tobacco. British American Tobacco; Monthly Report for October 1997. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rlg34a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1997. 1997 Brand Plan 555: Cambodia. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gbr34a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anon. British American Tobacco; Europe Export Markets Company Plan 1997–1999. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xfv14a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anon. British American Tobacco; 555 Business Review 1997. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kko93a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1998. Lucky Strike—1998 Business Review Market: Czech Republic. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/psm63a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1999. May–Oct. Venezuela—‘Music Experience’. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/isn71a99. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anon. British American Tobacco; [23 February 1999]. Communication Brief. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nkx23a99. [Google Scholar]

- 47.François G, Mahmood A. British American Tobacco; [23–24 February 1998]. Hungary Trip Notes. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yzb71a99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1999. Brand Plan 1999 (Mauritius): Benson & Hedges. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vtz82a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anon. British American Tobacco; Benson & Hedges: Ministry of Sound Gold Tour SA—Tour Presentation and Evaluation. No Date. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uwz04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Today’s News. British American Tobacco; [19 November 1998]. Today’s News—19 November 1998—email sent by O’Connell, Brian. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jip73a99. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kremer B. Brown & Williamson; [19 March 1999]. Ministry of Sound Fax to Ron Reinders. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wkr91d00. [Google Scholar]

- 52.British Heart Foundation Action on Smoking and Health. British American Tobacco; [15 August 1994]. ASH Information Service. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yyd54a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 53.KBA Marketing. RJ Reynolds; [5 March 1997]. 1997 Training Budget. Estimated Expenditures—KBA Marketing Fax to Camel. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dxg61d00. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prado SC. British American Tobacco; [10 February 1999]. Reuniao de 9/2/99. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cfm04a99. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hammond R. World Health Organization; Tobacco Advertising & Promotion: The Need for a Coordinated Global Response. http://www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/ROSS2000X.pdf 2000 Jan 7-9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Myers M. Alicia Keys sets example for entertainment industry by withdrawing tobacco sponsorship of Indonesia concert. 2008. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/Script/DisplayPressRelease.php3?Display=1093.

- 57.Limao DJ. Lucky Strike Club Fumadores—Clube fumadores/ Lucky Strike - 01/23/09. [Online Blog] 2009 [cited 18 December 2009]; Website featuring news about a a London DJ visiting Barcelona club that is apparently owned by BAT’s Lucky Strike and allows indoor smoking during its music events.]. Available from: http://djlimao.com/2009/01/23/lucky-strike-club-fumadores-clube-fumadores-lucky-strike-012309/

- 58.Marco Pardo Design Studio. CLUB LHAÜS / MADRID / 2006. 2009 [cited 23 December 2009; Lucky Strike Club interior design]. Available from: http://www.marcopardo.com/lucky_m.html.

- 59.Marco Pardo Design Studio. CLUB LHAÜS/VALENCIA/2008. 2009 [cited 23 December 2009; Lucky Strike Club interior design]. Available from: http://www.marcopardo.com/lucky_v.html.

- 60.Marco Pardo Design Studio. CLUB LHAÜS/SEVILLA/2007. 2009 [cited 23 December 2009; Lucky Strike Club interior design]. Available from: http://www.marcopardo.com/lucky_s.html.

- 61.Hafez N, Ling PM. How Philip Morris built Marlboro into a global brand for young adults: implications for international tobacco control. Tob Control. 2005;14:262–71. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Winebrenner J. British American Tobacco; YAUS Project. 04 November 1996. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pru53a99. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anon. British American Tobacco; Project Common Ground. No Date. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nru53a99. [Google Scholar]

- 64. headlightvision. Common Ground: Towards a Positioning for Lucky Strike. Presentation by Headlightvision Miami November 1997. November 1997. Brown & Williamson. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mtt91d00.

- 65.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1998. Global Business Review 1998. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vxj55a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anon. British American Tobacco; [20 May 1997]. International Brand: Business Reviews. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cda92a99. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1997. Dec, Monthly Report for December 1997. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mln34a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anon. British American Tobacco; 1996. 1996 Lucky Strike Business Review. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rku53a99 (estimated date) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wessel P, Castano C, von Brockhusen C. Lucky Strike USIB Group. British American Tobacco; [7 June 1996]. Project Ozone—Lucky Strike BTL Best Practice. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nfy63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anon. British American Tobacco; What do the London Underground, an MOS Pass and a Norwegian Dancer have in Common? No Date. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ykk82a99. [Google Scholar]

- 71.British American Tobacco. British American Tobacco; 1999. Jul, Clubber: Magazine of British American Tobacco No. 1 July 1999. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cyb71a99. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reinders R. British American Tobacco; ROAR. 1 November 1996. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tjy63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anderson S, Hastings G, MacFadyen L. Strategic marketing in the UK tobacco industry. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:481–6. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00817-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization. 2003. The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: A Primer. [Google Scholar]

- 75.World Health Organization. [2 September 2008]. Elaboration of guidelines for implementation of Article 13 of the Convention: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anon. British American Tobacco; Get Lucky Regulars and New Lights. No Date. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ygz63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anon. British American Tobacco; [29 March 1996]. Lucky Strike Presents the Ministry of Sound Tour: Kings College. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rey63a99. [Google Scholar]