Abstract

Recurrences of Hodgkin's Lymphoma (HL) 5 years after the initial therapy are rare. The aim of this study is to report a single centre experience of the clinical characteristics, outcome, and toxicity of pts who experienced very late relapses, defined as relapses that occurred 5 or more years after the achievement of first complete remission. Of 532 consecutive pts with classical HL treated at our Institute from 1985 to 1999, 452 pts (85%) achieved a complete remission. Relapse occurred in 151 pts: 135 (29.8%) within 5 years and 16 over 5 years (3.5%, very late relapses). Very late relapses occurred after a median disease-free interval of 7 years (range: 5–18). Salvage treatment induced complete remission in 14 pts (87.5%). At a median of 4 years after therapy for very late relapse, 10 pts (63%) are still alive and free of disease and 6 (37%) died (1 from progressive HL, 1 from cardiac disease, 1 from thromboembolic disease, 1 from HCV reactivation, and 2 from bacterial infection). The probability of failure-free survival at 5 years was 75%. The majority of deaths are due to treatment-related complications. Therapy regimens for very late relapse HL are warranted to minimize complications.

1. Introduction

With MOPP/ABVD or ABVD regimens more than 70% of patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) can effectively be cured. Fewer than 30% of patients, particularly in advanced stage, may relapse after first-line treatment [1–3].

Several clinical and laboratory features have been used to predict progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), in order to adjust therapy according to the risk of relapse. These features include age, sex, bulky disease, Ann Arbor stage IV, bone marrow involvement, anaemia, high serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or beta2-microglobulin [4–8], serum interleukin 10, and soluble CD30 [9–12].

Relapses usually occur within the first 3 years and a second complete remission can be achieved using treatment tailored according to disease extent at relapse [7] and previous treatment [13–16]. Few patients with documented very late relapses have been closely analyzed in the literature [17–31].

The aim of this study was to describe the incidence, clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome of very late relapse patients (defined as relapse occurring more than 5 years after complete remission) in a series of 532 consecutive patients with classical HL treated in our institution.

2. Patients and Methods

From 1985 to 1999, 532 consecutive previously untreated patients with classical HL were evaluated and treated at the Hematology Department of the University of Bari, Italy.

All patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor staging system. Initial evaluation included a complete medical history and physical examination, blood cell count and serum biochemistry profile, thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT), and bone marrow biopsy at diagnosis and at relapse.

Response to treatment was defined according to the International Working Group recommendations [32].

Patients in complete remission after first-line chemotherapy were included in this study; a followup was carried out with clinical examination, blood counts, biochemical tests, chest X-ray or thoracic CT, and abdominal CT or ultrasound, performed every 3 months during the first 2 years after treatment completion, every 6 months during the following 3 years, and annually thereafter, with a median followup of 12 years.

In all patients who relapsed, a second biopsy was performed to prove the HL histology of relapse.

3. Statistical Analysis

STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies were followed [33].

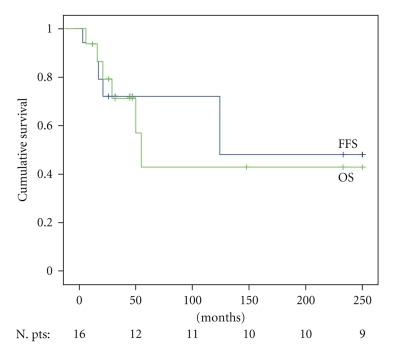

OS and FFS were estimated according to the Kaplan Meier product limit method.

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of the very late relapse to the last visit or death. Failure-free survival (FFS) was calculated from the date of very late relapse until documented relapse from CR after salvage therapy, disease progression following incomplete response to salvage therapy, or death, whatever came first. Deaths from unrelated causes were censored.

4. Results

After first-line therapy, 452 patients (85%) achieved complete remission (CR). 135 (29.8%) relapsed within 5 years (102 patients relapsed <3 years and 33 between 3 and 5 years) and 16 (3.5%) had very late relapse (>5 years).

The distribution of patients and relapse characteristics as a whole, and divided according to type of relapse, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics of HL in complete remission after first-line chemotherapy.

| All | Early relapse | Late relapse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 452 | 135 | 16 |

| Median age (range) | 31 (14–86) | 36 (16–79) | 37 (16–70) |

| Male/Female | 244/208 | 81/54 | 6/10 |

| Stage I-II | 271 (60%) | 52 (39%) | 10 (62%) |

| Stage III-IV | 181 (40%) | 83 (61%) | 7 (44%) |

| B symptoms | 158 (35%) | 58 (43%) | 12 (75%) |

|

| |||

| Histology: | |||

| NS | 275 (61%) | 73 (54%) | 9 (56%) |

| MC | 168 (37%) | 58 (43%) | 7 (44%) |

| LD | 9 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

NS: nodular sclerosis; MC: mixed cellularity; LD: Lymphocyte depletion.

The incidence rate of very late relapse after 5-year disease-free interval was 3.5%.

The characteristics and the treatments of the patients in very late relapse are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients characteristics of HL with very late relapse.

| Time to relapse | AGE at DG | Sex | Histol. | First-Line regimen | Lymphoma localization | Therapy | Responce | Second relapse | Cause of death | OS | FFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at diagnosis | at relapse | at relapse | mths | mths | |||||||||

| 1 | 5 | 46 | F | NS | MOPP/ABVD | INFRA | SUPRA | MOPP/ABVD | CR | YES | GRAM- sepsis | 55 | 17 |

| 2 | 5 | 23 | F | MC | MOPP/ABVD | INFRA | SUPRA | MOPP/ABVD | CR | NO | 250 | 250 | |

| 3 | 5 | 70 | M | NS | MOPP + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | SUPRA | MOPP/ABVD | PR | Disease progr. | 16 | 16 | |

| 4 | 8 | 20 | F | NS | HDS-ASCT + I.F.Radioth. | INFRA + SUPRA | INFRA | BEACOPP | CR | NO | 32 | 32 | |

| 5 | 18 | 37 | F | NS | MOPP + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | INFRA | ABVD | CR | NO | 32 | 32 | |

| 6 | 8 | 20 | F | MC | MOPP/ABVD + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | INFRA + SUPRA | ABVD | CR | NO | 233 | 233 | |

| 7 | 5 | 16 | F | NS | MOPP | INFRA + SUPRA | INFRA | ABVD | CR | YES | 148 | 124 | |

| 8 | 5 | 66 | F | MC | MOPP + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | INFRA | ABVD | CR | NO | 47 | 47 | |

| 9 | 5 | 56 | F | MC | MOPP/ABVD | SUPRA | INFRA | MOPP/ABVD | CR | NO | Tromboembolic D. | 8 | 8 |

| 10 | 11 | 32 | F | NS | MOPP + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | SUPRA | ABVD | CR | YES | GRAM- sepsis | 21 | 21 |

| 11 | 10 | 22 | F | MC | HDS-ASCT + I.F.Radioth. | INFRA + SUPRA | INFRA | BEACOPP | CR | NO | 8 | 8 | |

| 12 | 9 | 68 | M | MC | I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | INFRA | VEPEM-B | CR | NO | 45 | 45 | |

| 13 | 6 | 52 | M | MC | MOPP | INFRA + SUPRA | SUPRA | ABVD | CR | NO | HCV reactivation | 29 | 29 |

| 14 | 7 | 35 | M | NS | MOPP/ABVD + I.F.Radioth. | INFRA + SUPRA | INFRA | MOPP/ABVD | CR | YES | cardiac failure | 50 | 30 |

| 15 | 7 | 18 | M | NS | MOPP/ABVD + I.F.Radioth. | INFRA + SUPRA | INFRA + SUPRA | ABVD | PR | 26 | 26 | ||

| 16 | 5 | 18 | M | NS | ABVD + I.F.Radioth. | SUPRA | SUPRA | IGEV-ASCT | CR | NO | 12 | 12 | |

4.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Very Late Relapses

The histologies of the 16 patients in very late relapses were mixed cellularity in 7 (44%) and nodular sclerosis in 9 (56%). The median age was 37 yrs (16–70); 10 patients were female and 6 were male.

Ten patients (62%%) had stage I-II. B symptoms were present in 12 patients (75%), and 7 (44%) had bulky disease. First-line treatment was either standard or according to investigational protocols active during the time the patient was diagnosed. The chemotherapy schedules used at diagnosis were: ABVD in 1 (6%), MOPP/ABVD in 8 (50%), and MOPP in 6 (38%). Two patients in partial remission after MOPP/ABVD underwent high-dose chemotherapy (BEAM) and autologous stem cell transplantation. Involved-field radiotherapy was performed in 11 (69%) patients. The median radiation dose was 30 Gy (range: 20–36). One patient was treated with radiotherapy alone at diagnosis.

4.2. Patients Characteristics at Relapse

Median time to late relapse was 7 years; very late relapses occurred 5 to 18 years after treatment start (Table 2).

The histologies of very late relapses were in all cases the same as at diagnosis.

Clinical presentation at relapse demonstrated a supradiaphragmatic localization in 6 cases (37%), infradiaphragmatic in 8 (50%) and located on both sides in 2 cases (13%).

Bulky nodal disease was observed in 4 patients (25%). Extranodal disease occurred in 1 patient (6%). B symptoms were present in 6 patients (37%).

One patient (6%) relapsed on the irradiated field (mediastinal); 5 (31%) relapsed in sites of bulky disease; in 6 patients (37%), the disease localization was different from the site at diagnosis.

4.3. Treatments of Very Late Relapse and Followup

Treatment of relapse consisted of chemotherapy alone in 13 pts (81%) and chemotherapy and radiotherapy in 3 (19%). Among 6 patients initially treated with MOPP/ABVD, 4 were retreated with MOPP/ABVD and 2 received ABVD. All 6 patients initially treated with MOPP received noncross-resistant chemotherapy, 5 with ABVD and 1 with MOPP/ABVD. Both patients who relapsed following MOPP/ABVD plus BEAM + ASCT received escalated BEACOPP. The only patient who relapsed after RT alone received VEPEM-B. Only 1 patient received HDT/ASCT as second-line treatment for very late relapse.

In 4 patients, the chemotherapy regimen was the same one used as front-line therapy, and all patients achieved a second complete remission.

6/16 patients failed salvage therapy (2 PR and 4 relapses), and 2 additional patients died in second CR due to thromboembolic disease and HCV infection, 2 and 29 months after the confirmation of second CR, respectively.

Of the 16 patients, 14 achieved a second complete remission (87%) and 9 patients are still alive and free of disease. Two patients achieved a partial remission.

The median followup was at 32 months (range: 8–250), 6 patients died (Table 2).

Four patients experienced a second relapse within 1 year from the second complete remission, and they relapsed in the same sites as at the first relapse. One of them was reinduced to CR with the IEV regimen and is still in CR with a followup of 24 months, the other three patients died from toxicity during chemotherapy salvage treatment (2 from Gram-negative septic shock, 1 of cardiotoxicity). The patient who died of cardiac failure had a cumulative dose of anthracycline of 300 mg/sqm (the median cumulative dose of anthracycline for all patients was 300 mg/sqm).

In addition, one patient died from thromboembolic disease, and one died from HCV reactivation without evidence of HL (Table 2).

Of the two patients in PR, one achieved a CR with the IEV regimen and is still in CR after 14 months of followup while the other one died of HL progression.

The estimated OS after late recurrence was 44% at 5 years. The estimated FFS was 75% at 5 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival and failure-free survival in 16 PTS with VLR HL. PTS: patients; VLR: very late relapses; FFS: failure-free survival; OS: overall survival.

5. Discussion

The majority of patients with HL can be cured with conventional chemotherapy (ABVD), radiotherapy, or both. Even though HL is curable, approximately 30% of all patients relapse and eventually die of disease progression or complications of therapy. [1–3]. Most studies focused on early relapses should lead to improved first-line treatment approaches and high survival rates. Much less is known about very late relapse in terms of incidence and outcome [17–31].

There is no consensus on the definition of very late relapse: three or five years have been proposed in various reports [17–27]. An interval of 5 years was chosen because the actuarial rate of relapse appeared to reach a plateau at 5 years [17–27].

The incidence of late relapse reported in previous studies was variable, from 3.5 to 8%. This difference is probably due to a different definition of the time of relapse (three, five years, or more) [17–31].

As the incidence of very late relapse in HL is higher than the incidence of HL in the general population, it suggests that this event represents a reactivation of the disease (in the same sites and with the same histology), rather than the development of a new HL [22]. The finding of persistent HL in autopsies of long survivors who died of apparently unrelated causes suggests that, for at least some patients with HL, clinical cure does not always mean the eradication of all the malignant cells [34]. Some authors have suggested that the circumstances that impaired the immune system may cause the recurrence [35]. At least part of the late recurrences of HL might be de novo emerging malignancies in patients at elevated genetic risk for developing HL [36]. The persistence of the same viral strain in early and very late relapse of Epstein-Barr virus is evidence that in HL such relapses are related to a single residual tumor cell clone [37, 38].

Herman et al. [25] reported that the actuarial risk of relapse after a 3-year disease-free interval was 13%. These investigators found that the occurrence of late relapse was significantly related to stage I disease and the nodular sclerosis histologic subtype. Another report, by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [22], showed a 3.5% incidence of very late relapse after a 5-year disease-free interval. That study showed that the incidence of late relapses was significantly correlated with male sex, B symptoms, mediastinal involvement, and treatment modality. The authors found that HL patients who experience a very late relapse have a similar survival to patients who are continuously disease-free. The actuarial incidence of very late relapse at 10 and 15 years in early stage patients was 4.8% and 8.3%, respectively. Similarly, the actuarial incidence of very late relapse at 10 and 15 years in patients of all stages was 4.4% and 8.0%, respectively, as reported by Vassilakopoulos et al. [27].

The investigators observed that patients with LH more often developed very late relapse when they were treated with less intensive therapy. In our series, two patients had very late relapse after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Another report [20] of patients in early stage HL revealed 4.6% of very late relapse (more than 4 years). These investigators found that these patients had better survival than did patients with early relapse.

Bodis et al. [22] reported that very late relapses in early stage patients were more frequent in males with B symptoms at diagnosis and mediastinal involvement, who had been treated with radiotherapy only (versus combined modality). Vassilakopoulos et al. [27], in an analysis of all stages, reported that very late relapses were more frequent in patients with more extensive disease at diagnosis, nonnodular sclerosing histology, who had been treated with chemotherapy only (versus combined modality). Also Brierly et al. [20] found age and B symptoms as predictors for late relapse in early stage patients.

The fact that in our study, 14 patients (87%) had stage I or II disease at the time of very late relapse could be due to the continuous followup of patients in complete remission.

No histological characteristics have been found to correlate with very late relapse risk, but more cases are necessary to draw definitive conclusions. There is no accurate means to identify patients at risk of very late relapse, and there is no absolutely safe point at which an individual patient may be considered cured of HL and at no risk of very late relapse [17–31].

In our study 11/16 patient had radiotherapy as part of their initial therapy, but only one patient relapsed in the radiotherapy field. Radiotherapy seems to be an important issue in preventing late relapse.

Patients who relapse within the first 3 years have more aggressive disease, and patients who relapse late have a more indolent disease that responds to further therapy [21, 22]. Very late relapse is adequately reinduced to complete remission by a second course of the primary treatment regimen, and so are still curable with conventional treatment, as documented by our 5 patients treated with the same therapy, who achieved a second complete remission. In fact, 5/6 patients treated with the same regimen (4 MOPP/ABVD to MOPP/ABVD, 2 MOPP/ABVD to ABVD) achieved a second CR, but 2/5 relapsed, and one is not evaluable for relapse due to early death. Thus the data presented in this study support that the administration of the same drugs is effective in inducing a second CR, but its potential in inducing long-term remissions (cure?) is questionable.

However, despite the high percentage of complete remissions (87%), 4 patients relapsed (second relapse) early (<1 years) while 4 patients died of toxicity (1 from cardiac disease, 1 from HCV reactivation, and 2 from gram negative sepsis). Another TRM due to pulmonary thromboembolism was observed in second complete remission, 2 months after the completion of chemotherapy.

In conclusion, very late relapse occurs in a small number of patients with HL, which emphasizes the need for continuous followup. Very late relapse is associated with a better survival than relapse occurring within the first 5 years from the time of diagnosis [20, 22]. Unfortunately, the majority of deaths of patients in very late relapse are related to treatment complications while deaths due to HL are unusual. Future treatment regimens for HL, including very late relapse, need to be designed to minimize complications.

References

- 1.Duggan DB, Petroni GR, Johnson JL, et al. Randomized comparison of ABVD and MOPP/ABV hybrid for the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease: report of an Intergroup trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(4):607–614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domínguez AR, Márquez A, Gumá J, et al. Treatment of stage I and II Hodgkin’s lymphoma with ABVD chemotherapy: results after 7 years of a prospective study. Annals of Oncology. 2004;15(12):1798–1804. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straus DJ, Portlock CS, Qin J, et al. Results of a prospective randomized clinical trial of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) followed by radiation therapy (RT) versus ABVD alone for stages I, II, and IIIA nonbulky Hodgkin disease. Blood. 2004;104(12):3483–3489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josting A, Wolf J, Diehl V. Hodgkin disease: prognostic factors and treatment strategies. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2000;12(5):403–411. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josting A, Rueffer U, Franklin J, Sieber M, Diehl V, Engert A. Prognostic factors and treatment outcome in primary progressive Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2000;96(4):1280–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fermé C, Bastion Y, Brice P, et al. Prognosis of patients with advanced Hodgkin’s disease: evaluation of four prognostic models using 344 patients included in the group d’etudes des lymphomes de l’adulte study. Cancer. 1997;80(6):1124–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(21):1506–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glimelius I, Molin D, Amini RM, Gustavsson A, Glimelius B, Enblad G. Bulky disease is the most important prognostic factor in Hodgkin lymphoma stage IIB. European Journal of Haematology. 2003;71(5):327–333. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viviani S, Notti P, Bonfante V, Verderio P, Valagussa P, Bonadonna G. Elevated pretreatment serum levels of IL-10 are associated with a poor prognosis in Hodgkin’s disease, the milan cancer institute experience. Medical Oncology. 2000;17(1):59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02826218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlen H, Kessler M, Sextro M, Diehl V, Tesch H. Poor clinical outcome of patients with Hodgkin’s disease and elevated interleukin-18 serum levels. Clinical significance of interleukin-10 serum levels for Hodgkin’s disease. Annals of Hematology. 2000;79(3):110–113. doi: 10.1007/s002770050564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassilakopoulos TP, Nadali G, Angelopoulou MK, et al. Serum interleukin-10 levels are an independent prognostic factor for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2001;86(3):274–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadali G, Tavecchia L, Zanolin E, et al. Serum level of the soluble form of the CD30 molecule identifies patients with Hodgkin’s disease at high risk of unfavorable outcome. Blood. 1998;91(8):3011–3016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro A, Bonfante V, Bonadonna G. Salvage chemotherapy with ABVD in MOPP-resistant Hodgkin’s disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1982;96(2):139–143. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-2-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tannir N, Hagemeister F, Velasquez W, Cabanillas F. Long-term follow-up with ABDIC salvage chemotherapy of MOPP-resistant Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1983;1(7):432–439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.7.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bierman PJ, Bagin RG, Jagannath S, et al. High dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic rescue in Hodgkin’s disease: long term follow-up in 128 patients. Annals of Oncology. 1993;4(9):767–773. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuen AR, Rosenberg SA, Hoppe RT, Halpern JD, Horning SJ. Comparison between conventional salvage therapy and high-dose therapy with autografting for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Blood. 1997;89(3):814–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamir D, Leibovitz I, Polyschuck I, Reitblat T, Lugassy G. Very late relapse of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2004;6(2):112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shihabi S, Deutsch M, Jacobs SA. Very late relapse of hodgkin’s disease: a report of five patients. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;24(6):576–578. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Carbonero R, Paz-Ares L, Arcediano A, Lahuerta J, Bartolome A, Cortes-Funes H. Favorable prognosis after late relapse of Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1998;83(3):560–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brierley JD, Rathmell AJ, Gospodarowicz MK, Sutcliffe SB, Pintillie M. Late relapse after treatment for clinical Stage I and II Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1997;79(7):1422–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Wit M, Hossfeld DK. Late relapse following Hodgkin’s diseaseSpätrezidive nach Morbus Hodgkin. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1994;119(14, article 536) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodis S, Henry-Amar M, Bosq J, et al. Late relapse in early-stage Hodgkin’s disease patients enrolled on European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer protocols. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(2):225–232. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinzani PL, Mazza P, Gherlinzoni F, et al. ’Very late’ relapses in Hodgkin’s disease patients: a rare but real phenomenon. Haematologica. 1992;77(5):435–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anselmo AP, Cartoni C, Panzini E, Enrici RM, Biagini C, Mandelli F. Recurrence of Hodgkin’s disease after 10 years: observation of 5 cases. Acta Haematologica. 1992;87(3):122–125. doi: 10.1159/000204737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman TS, Hoppe RT, Donaldson SS, Cox RS, Rosenberg SA, Kaplan HS. Late relapse among patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1985;102(3):292–297. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-3-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanofsky JR, Golomb HM, Vardiman JE, Sweet DL, Ultmann JE. Late relapses in Hodgkin disease. American Journal of Hematology. 1981;10(1):31–36. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassilakopoulos TP, Angelopoulou MK, Siakantaris MP, et al. Very late relapses in patients with Hodgkins lymphoma. Haematologica. 2005;90(supplement 2):p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimopoulos MA, Kostis E, Anagnostopoulos A, Dalezios M, Papadimitris C, Papadimitriou C. Very late relapse of Hodgkin’s disease after 24 years of complete remission. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 1997;28(1-2):215–217. doi: 10.3109/10428199709058350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Illes A, Banyai A, Vadasz G, Szegedi G. Relapse of Hodgkin’s disease after ten years. Oncology. 1995;52(4):284–286. doi: 10.1159/000227474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KM, Spittle MF. Hodgkin’s disease: a case of late relapse. Clinical Oncology. 1993;5(6):p. 399. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim EM. Late relapse of Hodgkin’s disease after 25 years. Indian Journal of Cancer. 1990;27(1):17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(4):1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(4):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strum SB, Rappaport H. The persistence of Hodgkin’s disease in long-term survivors. American Journal of Medicine. 1971;51(2):222–240. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jouet JP, Buchet-Bouverne B, Fenaux P, et al. Influence of pregnancy on the activity of Hodgkin’s disease? Presse Medicale. 1988;17(9):423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siebert R, Fosså A, Kaiser W, Ferencik AWS, Seeber S, Nowrousian MR. Recurrence of Hodgkin’s disease after 10 or more years: late relapse or de-novo malignancy due to HLA-DPB1*0301-linked susceptibility? Leukemia and Lymphoma. 1997;26(1-2):121–125. doi: 10.3109/10428199709109166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brousset P, Schlaifer D, Meggetto F, et al. Persistence of the same viral strain in early and late relapses of Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin’s disease. Blood. 1994;84(8):2447–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coates PJ, Slavin G, D’Ardenne AJ. Persistence of Epstein-Barr virus in Reed-Sternberg cells throughout the course of Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Pathology. 1991;164(4):291–297. doi: 10.1002/path.1711640404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]