Abstract

Dietary supplements have been suggested in the prevention of the common cold, but previous investigations have been inconsistent. The present study was designed to determine the preventive effect of a dietary supplement from fruits and vegetables on common cold symptoms. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, healthcare professionals (mainly nursing staff aged 18–65 years) from a university hospital in Berlin, Germany, were randomised to four capsules of dietary supplement (Juice Plus+®) or matching placebo daily for 8 months, including a 2-month run-in period. The number of days with moderate or severe common cold symptoms within 6 months (primary outcome) was assessed by diary self-reports. We determined means and 95 % CI, and differences between the two groups were analysed by ANOVA. A total of 529 subjects were included into the primary analysis (Juice Plus+®: 263, placebo: 266). The mean age of the participants was 39·9 (sd 10·3) years, and 80 % of the participants were female. The mean number of days with moderate or severe common cold symptoms was 7·6 (95 % CI 6·5, 8·8) in the Juice Plus+® group and 9·5 (8·4, 10·6) in the placebo group (P = 0·023). The mean number of total days with any common cold symptoms was similar in the Juice Plus+® and in the placebo groups (29·4 (25·8, 33·0) v. 30·7 (27·1, 34·3), P = 0·616). Intake of a dietary supplement from fruits and vegetables was associated with a 20 % reduction of moderate or severe common cold symptom days in healthcare professionals particularly exposed to patient contact.

Keywords: Common cold, Dietary supplement, Encapsulated juice powder concentrate

The common cold is the most frequent acute illness in industrialised societies. It is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract, caused by a variety of viruses, with rhinoviruses and corona viruses as the most common. The leading symptoms include sneezing, runny or congested nose, sore throat, headache and coughing, typically lasting for about 5–10 d. On average, adults experience two to four colds per year( 1 ). Prevalence of the common cold is clearly associated with the seasons. In the Northern hemisphere, the frequency of common cold infections increases in autumn and winter and decreases in spring( 1 ).

The course of the common cold is usually benign; however, it is a leading cause of absence from work and doctor visits, responsible for a marked economic burden including lost productivity and treatment costs. In the USA, the common cold is estimated to cause twenty-three million days of absence from work and cost $2 billion for over-the-counter medication( 2 ).

Since there is no causal treatment for the common cold, therapy focuses on symptom relief. In addition, preventive strategies for the common cold include lifestyle measures such as avoiding infected people and regular hand washing during the winter( 3 ). Dietary supplements including herbs and vitamins have been suggested in the prevention of the common cold, but previous investigations including studies with Echinacea, an herbal supplement, found supplements to be not effective for the prevention of the common cold( 4 ), or yielded inconsistent results (several studies on the effect of vitamin C). A randomised controlled trial from Japan found a significant reduction of common cold episodes over a period of 5 years in participants with high-dose v. low-dose vitamin C intake, but no reduction in the duration or severity of the common cold( 5 ). A recently published Cochrane review has found no effect of vitamin C intake compared to placebo for the incidence of the common cold (with the exception of participants exposed to severe physical stress or very cold environments), while an overall reduction of 8 % in common cold duration was reported( 6 ).

Juice Plus+® (NSA, Collierville, TN, USA) is a dietary supplement composed primarily of juice powder concentrate from fruits and vegetables. It contains several antioxidants including vitamin C, vitamin E, β-carotene and folate, and it has been shown to increase plasma levels of antioxidants and folate and of γδ T cells, which are believed to strengthen immune function( 7 ). One randomised study reported reduction in work days lost due to illness in the Juice Plus+® group compared to the placebo group( 8 ); however, the clinical benefit for preventing or reducing common cold symptoms over the winter season has not yet been tested in a large adult population. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the effect of Juice Plus+® on the severity and frequency of common cold symptoms in a population considered at particular exposure.

Methods and materials

Study design and patients

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, volunteer participants were eligible for enrolment if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: 18–65 years of age; able and willing to take the active or placebo capsules over the entire study period; healthcare professionals with direct patient contact (physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, etc.); written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were acute influenza or common cold present at the time of enrolment; known or suspected hypersensitivity or allergy to one of the ingredients of Juice Plus+®; any alarming symptoms such as significant unintentional weight loss, fever, or any other sign indicating serious or chronic disease including suspected or confirmed malignancy, or other significant cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, pancreatic or liver disease; alcohol addiction or drug abuse; pregnancy or lactation; language limitations regarding interviews and questionnaires.

The subjects were recruited by advertisements on bulletin boards and the intranet in the Charité University Medical Center in Berlin, Germany, and screened by study staff. The period of enrolment was from 12 September 2008 to 2 October 2008.

The subjects were allocated to the Juice Plus+® group or the placebo group by computerised simple randomisation. The dietary supplement and the matching placebo were provided by the study sponsor and packaged in identical white bottles. Subjects were required to take four study capsules daily including two capsules in the morning with breakfast and two capsules in the evening with dinner over a period of 8 months.

Baseline characteristics of subjects were assessed after screening and inclusion in the study by questionnaire. Common cold symptoms were documented by participants with a validated common cold diary during the entire study period( 9 ). The diary includes the following four symptom categories: cough, nasal symptoms, throat symptoms and general symptoms (fever, headache and aches), each with a possible severity of none, light, moderate or severe.

The primary outcome was the number of days with at least moderate (i.e. moderate or severe) common cold symptoms within 6 months after an 8-week run-in phase calculated from the common cold diary. Secondary outcomes of the present study were days with any common cold symptoms, common cold-related days unable to work, days with common cold-related medication use and health-related quality of life (SF-12). Compliance was assessed by pill count from returned bottles by study staff and calculated as proportion of capsules taken.

The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance to International Conference on Harmonisation-Good Clinical Practice, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board (Charité Ethics Committee). The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00778648). Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 235 in each group (470 in total) was estimated to yield 90 % power to detect a difference in means of 3 d of at least moderate common cold symptoms (assumption in placebo group: mean of 20 d; assumption in Juice Plus+® group: mean of 17 d) assuming a common standard deviation of 10 d and using a two-sided t test with a significance level of 0·05. Based on this calculation and an assumed lost-to-follow-up rate of 10 %, a total of 524 subjects were required for the study.

Descriptive analyses were done for all baseline variables, and are given as means and standard deviations or frequency with percentage according to the scale of the variable. For the primary outcome, means and 95 % CI are reported, and the difference between study groups was analysed using ANOVA with a significance level of 0·05. Secondary outcomes were analysed likewise with P values considered exploratory. All the analyses (including randomisation) were done in SPSS 17.0 or Statistical Analysis Systems 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

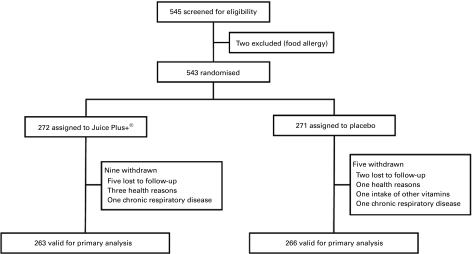

Of a total of 545 screened subjects, two subjects were excluded because of food allergies. Thus, 543 subjects were randomised, of those 271 subjects belong to the placebo group and 272 subjects belong to the Juice Plus+® group. Twelve subjects (2·2 %, four in placebo group and eight in Juice Plus+® group) were withdrawn because of dropout including lost to follow up or health reasons during the run-in period without any data on common cold symptoms, and two participants were withdrawn due to chronic respiratory disease, one in the Juice Plus+® group and one in the placebo group. Therefore, the primary analysis groups included 263 subjects randomised to Juice Plus+® group and 266 randomised to placebo group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial participant flow.

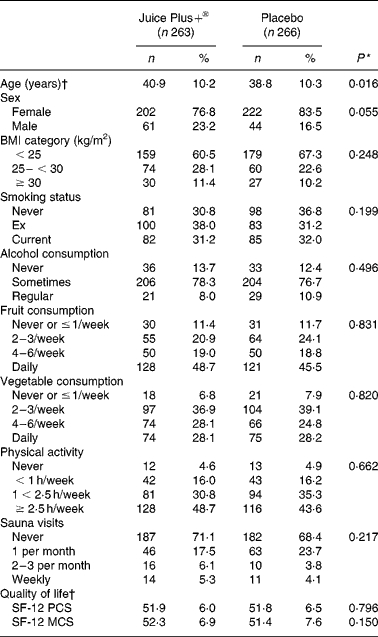

Most baseline characteristics of study participants were similar between the two groups (Table 1). The majority of the participants were females (77 % in Juice Plus+® group and 84 % in placebo group). The mean age of the study participants was 40·9 (sd 10·2) years in the Juice Plus+® group and 38·8 (sd 10·3) years in the placebo group. About one-third of the population were current smokers. About 20 % reported physical activity of less than 1 h/week, and 47 and 28 % reported daily intake of fruits and vegetables, respectively (Table 1). Influenza vaccination was obtained during the study period by 16 % in the Juice Plus+® group and 19 % in the placebo group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

(Number of participants and percentages)

PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary.

P value from two-sample t test or χ2 test.

Age and quality of life are given in terms of means and standard deviations.

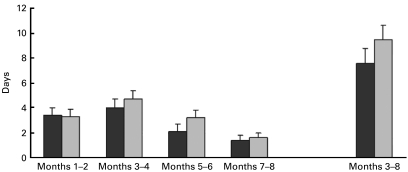

The mean number of days with at least moderate common cold symptoms within 6 months after the run-in period (primary outcome) was 7·6 (95 % CI 6·5, 8·8) in the Juice Plus+® group and 9·5 (95 % CI 8·4, 10·6) in the placebo group (P = 0·023). The mean number of days with at least moderate common cold symptoms for the entire study period (including run-in phase) in the control and intervention group is given in Fig. 2, categorised with respect to time period of occurrence. A disaggregation of the primary outcome yielded 5·2 (95 % CI 4·5, 6·0) d with moderate symptoms in the Juice Plus+® group and 6·0 (95 % CI 5·3, 6·8) d in the placebo group (P = 0·139), and 2·4 (95 % CI 1·8, 3·0) d with severe symptoms in the Juice Plus+® group and 3·5 (95 % CI 2·9, 4·1) d in the placebo group (P = 0·010). Adjusting the analysis of the primary outcome for baseline characteristics (e.g. age and sex) yielded results similar to the unadjusted results.

Fig. 2.

Number of days with at least moderate common cold symptoms for the entire study

period including run-in period (months 1–2) and within 6 months after the

run-in period (months 3–8, primary outcome). Values we means, with

95 % CI represented by vertical bars. ■, Juice

Plus+®;  , placebo.

, placebo.

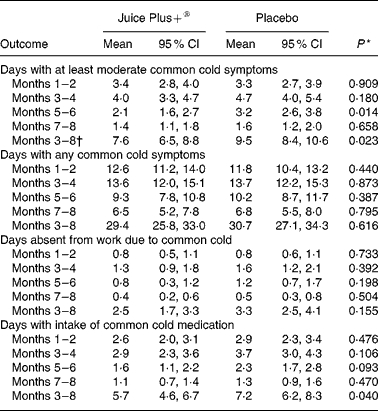

Both the groups were similar with regard to mean days with any common cold symptoms within 6 months after the run-in period (29·4 in Juice Plus+® group v. 30·7 in placebo group, P = 0·616; Table 2). Participants in the Juice Plus+® group reported fewer days absent from work during this period (2·5 v. 3·3 d), but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0·155). Participants in the Juice Plus+® group reported fewer days with intake of medication for common cold than participants in the placebo group (5·7 v. 7·2 d, P = 0·040; Table 2).

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes with respect to time period of occurrence and within 6 months after 8-week run-in phase (months 3–8).

(Mean values and 95 % confidence interval)

P values from ANOVA.

Primary outcome.

Health-related quality of life was similar in both the groups at baseline (Table 1) and remained so during the study period (data not shown) with no significant differences for all but one time point. At month 8, the mean SF-12 physical component summary was 51·9 (95 % CI 51·1, 52·6) in the Juice Plus+® group and 51·5 (95 % CI 50·7, 52·4) in the placebo group (P = 0·566), while the mental component summary was 53·7 (95 % CI 52·8, 54·5) and 53·1 (95 % CI 52·2, 53·9), respectively (P = 0·313). Overall compliance was high in both the groups with 96·0 % in the Juice Plus+® group and 96·5 % in the placebo group.

Discussion

Intake of a dietary supplement from fruits and vegetables was associated with a 20 % reduction in days of moderate or severe common cold symptoms during the 6-month study period. The number of days with any common cold symptoms was not significantly reduced. Thus, the intervention appeared effective in the attenuation of symptom level. This finding is corroborated by fewer days with intake of common cold medication and a trend towards fewer days absent from work due to the common cold in the verum v. the placebo group.

The present study included an 8-week run-in phase, because it was assumed that the intervention would not be effective immediately. Indeed, no differences between the two groups were observed within the first 2 months of the study, while later in the trial (months 3–6), a reduction in the days with moderate or severe common cold symptoms was found. It appears possible that an earlier and longer run-in phase would have resulted in a larger difference between the Juice Plus+® group and the placebo group.

Because the present study included only health professionals and primarily nurses, a predominantly female professional in Germany, the majority of participants were female, limiting the generalisability of the results. In addition, healthcare professionals may differ from the general population regarding socio-economic variables or health-related lifestyle. However, the reduction of days with common cold symptoms was observed quite consistently among several subgroups (e.g. participants with higher or lower fruit or vegetable consumption).

The primary outcome was assessed by a common cold diary, yielding a subjective measure of days with the common cold. However, it would be difficult to objectively assess the number of days with the common cold in a population consistently over several months. From a patient's perspective, the subjectively judged days with a cold might be the outcome of choice, and due to the double-blind design, the effect of the intervention should not be biased.

Given the widespread utilisation of concentrated dietary products, the present study has potentially important public health relevance. To our knowledge, it is the first randomised investigation focusing on the benefits of juice powder concentrate in subjects particularly exposed to patient contact. The confirmation of the present findings in other populations could contribute to the growing scientific basis of assessing the clinical importance of dietary supplements from fruits and vegetables.

In conclusion, intake of Juice Plus+® was associated with fewer number of days with at least moderate common cold symptoms. Whether long-term intake of Juice Plus+® could further reduce severity or even the frequency of common cold symptoms and the possible underlying mechanisms should be assessed in future studies.

Acknowledgements

S. R. was involved in designing the trial and writing the trial protocol, calculated the sample size, analysed data, and drafted and finalised the manuscript. M. N. was involved in designing the trial and writing the trial protocol, supervised patients' recruitment and data collection, analysed data, and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. S. N. W. initiated, designed and supervised the trial as principal investigator, and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and approved the final version of the manuscript. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest. The source of funding of this trial was NSA. The sponsor participated in the discussion regarding the design of the study and provided the Juice Plus+® and placebo capsules. The sponsor obtained no data and was not involved in the interpretation of the results.

References

- 1.Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet . 2003;361:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner RB. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of the common cold. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 1997;78:531–539. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63213-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Common Cold . Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 2007. [accessed 7 August 2007]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melchart D, Walther E, Linde K. et al. Echinacea root extracts for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections: a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Arch Fam Med . 1998;7:541–545. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsubono Y. et al. Effect of vitamin C on common cold: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr . 2006;60:9–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas R, Hemila H, Chalker E, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007 . 2007. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. issue 3, CD000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nantz MP, Rowe CA, Nieves C Jr. et al. Immunity and antioxidant capacity in humans is enhanced by consumption of a dried, encapsulated fruit and vegetable juice concentrate. J Nutr . 2006;136:2606–2610. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamprecht M, Oettl K, Schwaberger G. et al. Several indicators of oxidative stress, immunity, and illness improved in trained men consuming an encapsulated juice powder concentrate for 28 weeks. J Nutr . 2007;137:2737–2741. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemila H, Douglas RM. Vitamin C and acute respiratory infections. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis . 1999;3:756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]