Abstract

Elevated level of homocysteine (Hcy) induces chronic inflammation in vascular bed, including glomerulus, and promotes glomerulosclerosis. In this study we investigated in vitro mechanism of Hcy-mediated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) induction and determined the regulatory role of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) to ameliorate inflammation. Mouse glomerular mesangial cells (MCs) were incubated with Hcy (75 μM) and supplemented with vehicle or with H2S (30 μM, in the form of NaHS). Inflammatory molecules MCP-1 and MIP-2 were measured by ELISA. Cellular capability to generate H2S was measured by colorimetric chemical method. To enhance endogenous production of H2S and better clearance of Hcy, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) genes were delivered to the cells. Oxidative NAD(P)H p47phox was measured by Western blot analysis and immunostaining. Phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK1/2) were measured by Western blot analysis. Our results demonstrated that Hcy upregulated inflammatory molecules MCP-1 and MIP-2, whereas endogenous production of H2S was attenuated. H2S treatment as well as CBS and CSE doubly cDNA overexpression markedly reduced Hcy-induced upregulation of MCP-1 and MIP-2. Hcy-induced upregulation of oxidative p47phox was attenuated by H2S supplementation and CBS/CSE overexpression as well. In addition to that we also detected Hcy-induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction was through phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2. Either H2S supplementation or CBS and CSE doubly cDNA overexpression attenuated Hcy-induced phosphorylation of these two signaling molecules and diminished MCP-1 and MIP-2 expressions. Similar results were obtained by inhibition of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 using pharmacological and small interferring RNA (siRNA) blockers. We conclude that H2S plays a regulatory role in Hcy-induced mesangial inflammation and that ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 are two signaling pathways involved this process.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinase 1/2

cardiovascular disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. A number of prospective observational studies have shown that hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), an elevated homocysteine (Hcy) level, is associated with vascular morbidity and mortality (6, 54). However, randomized clinical trials designed to lower Hcy levels in patients with cardiovascular disease have failed to show any clinical benefit despite a demonstrable reduction in serum Hcy levels (15, 27, 46). While the reasons for the failure of the trials are not known, one major limitation in these trials was the failure to demonstrate reduced tissue levels of Hcy. Folic acid, the treatment used to reduce Hcy in most trials, may in fact promote tissue uptake of Hcy. This seemingly paradoxical effect has been demonstrated with other hormones and growth factors, such as insulin (11), which decreases plasma levels of amino acids by increasing tissue uptake. Previously, we demonstrated elevated tissue levels of Hcy in the kidney (37) and heart tissue (33) of hyperhomocysteinemic mice with alloxan-induced diabetes mellitus. We also demonstrated that the level of cystathione γ-lyase (CSE), an enzyme responsible for conversion of Hcy to H2S, a potent antioxidant, vasorelaxant, and antihypertensive agent, was decreased in the kidney of another model of HHcy, the uninephrectomized cystathionine β-synthase heterozygous (CBS+/−) mice (36). In these animals, decreased endogenous H2S production associated with decreased CSE activity. Supplementation with H2S resulted in increased CSE activity.

Several laboratories, including our own, have shown that Hcy induces glomerular injury (34, 56), in part mediated through the induction of inflammatory molecules (36). In glomerular injury, similar to other injuries, circulating monocytes through upregulated inflammatory molecules adhere to the glomerular vessel wall, roll and migrate to the site of injury. This is a physiological defense mechanism and migrated monocytes through a sequence of events modulate extracellular matrix, resulting in matrix deposition and glomerulosclerosis in the glomerulus. This ultimately causes chronic kidney disease (CKD) and leads to declined renal function (4). Cytokine- and chemokine-mediated inflammation is a major contributory factor in the development and progression of CKD. Clinical evidence show that elevated Hcy levels in CKD patients have been linked to the inflammatory state associated with CKD (31, 53). Specifically, Hcy induces the expression of cytokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and chemokines, such as macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), in cultured mesangial cells (4, 40). The mechanism of such induction, however, is not well understood.

Multiple other factors are also involved in the inflammation associated with CKD, such as oxidative stress (32), hyperleptinemia (28), C-reactive protein (CRP) (44), nitric oxide (NO) (23), and carbon monoxide (CO) (13) among others. Recently, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), an endogenous gaseous molecule, has been identified as major regulator of inflammatory responses (22, 26). We have previously shown that H2S prevents HHcy-associated renal damage (34) and regulates glomerular matrix remodeling and inflammation during HHcy (36). Others have reported protective effects of H2S on renal function and inflammation (2). Under normal physiological conditions Hcy is metabolized by two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) (1, 17), and one pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-independent enzyme 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) (41–42) to produce H2S. Although Hcy is one of the precursors of H2S and high levels of Hcy seem to promote H2S generation, Chang et al. (3) have reported that HHcy inhibited CSE in myocardial tissue resulting in decreased H2S production. In accordance with their finding, our recent report (36) suggests that CSE expression was also attenuated in the renal cortical tissue of HHcy mice. These previous findings led us to hypothesize that CBS and CSE gene therapy may protect renal tissue from Hcy-mediated injury and inflammation through promoting H2S generation during HHcy. Also, signaling mechanism of this pathway may provide further insight to modulate HHcy-associated renal inflammatory disease processes. Our in vitro data suggest that HHcy causes upregulation of inflammatory molecules MCP-1 and MIP-2 in kidney mesangial cells (MCs) through attenuated H2S generation. Overexpression of CBS/CSE gene mitigates these inflammatory molecules in MCs by increasing H2S generation through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)- and and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK1/2)-dependent pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Mouse kidney glomerular MCs of 7- to 10-wk-old mice were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). We used mouse cells, instead of human cells, to maintain consistency of our experimental model (34, 36). These cells were cultured and maintained in DMEM/F-12 (50/50) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). T-25 flasks were kept in a humid chamber at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air and allowed to grow at ∼80% confluent. Flasks were then trypsinized (0.25% trypsin, 0.1% EDTA in HBSS without Ca2+, Mg2+, and sodium bicarbonate; Mediatech), and cells were washed with DMEM and plated onto 12-well TPP (Techno Plastic Products, Trasadingen, Switzerland) cell culture plate. Cells were allowed to grow about 80% confluence before experiments. Termination of our experiments was based on our previous reports (36, 38).

Antibodies and reagents.

Mouse monoclonal CBS and CSE antibodies were from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Phospho-SAPK/JNK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2, and p47phox antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Inhibitors of MEK1 (PD98059) and SAPK/JNK1/2 (SP600125) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). l-Hcy was from Chem-Impex International, Wood Dale, IL. Anti-β-actin antibody, DL-methionine, l-cysteine, and other analytical reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Detection of MCP-1 and MIP-2.

MCP-1 in the cell lysate and MIP-2 in the cell culture supernatant were detected by ELISA (Biotech, Norcross, GA) following manufacturer's instructions.

Expression vectors and CBS gene transfections.

CBS cDNA and green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA was provided by Jeffrey Taub (50). Cystathionine γ-lyase (pME18S-CSE-HA) was kindly provided by Dr. Hideo Kimura (National Institute of Neuroscience, 4-1-1 Ogawahigashi, Kodaira, Tokyo, 187-8502, Japan). The cDNAs were subcloned and purified using QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit (Chatsworth, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and MCs were transfected as described previously (38).

Measurement of H2S.

The capability of MCs to generate H2S was determined according to the previously adopted method (39).

Immunostaining to detect p47phox.

MCs were grown in eight-well chamber slide and transfected with CBS, CSE, or both the cDNAs with appropriate controls. Cells were then incubated with l-Hcy (75 μM) in a cell culture incubator for 48 h. At the end of incubation, cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked with 1% BSA for 15 min followed by two washes with PBS 5 min each. Cells in the chamber slides were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde containing 0.25% l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS (3×, 5 min each) and blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h. After two washes of 5 min each, primary antibody (p47phox, 1:100 dilutions in 1% BSA) was added and incubated for overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation. Excess antibody washed by PBS (3×, 5 min each) wash and secondary fluorescence conjugated (Texas red) antibody (1:500 dilutions in 1% BSA) was added and incubated for 2 h at RT. Unbound secondary antibody removed by PBS wash (3×, 5 min each) and fluorescence was visualized in a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview 1000) with appropriate filter.

Western blot analyses.

The cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Boston BioProducts, Worcester, MA), protein content was measured using BCA method, and equal amount of protein was separated onto 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with appropriate antibodies following our earlier adopted method (38).

HPLC analysis.

Hcy and Cys were extracted from cell culture supernatant and analyzed as described previously (38). The method was adopted from Malinow et al. (29).

Statistical analysis.

Values are given as means ± SE from “n” numbers of experiments in each group as mentioned in each of the figure legends. The difference between mean values of multiple experiments was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffés post hoc analysis. Comparisons between groups were made with the use of Student's independent t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was accepted significance.

RESULTS

Hcy induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 by attenuating H2S production.

To determine whether Hcy stimulates the production of inflammatory molecules in mouse mesangial cells (MCs), we treated MCs with increasing concentrations of Hcy as demonstrated in Fig. 1A. At a concentration of 50 μM, Hcy significantly stimulated MCP-1, but not MIP-2, when compared with control. Both of these molecules, however, robustly increased at the 75 μM dose of Hcy, with little increase thereafter (Fig. 1A). Two amino acids in the Hcy synthesis and metabolism pathways, methionine and cysteine, respectively, had no effect in the expressions of these two molecules at the 75 μM dose (Fig. 1A, inset).

Fig. 1.

A: homocysteine (Hcy) dose dependently induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) in mouse glomerular mesangial cells (MCs). MCs were plated onto 12-well cell culture plate as described in the materials and methods. Cells were treated with l-Hcy (0–100 μM) for 48 h as shown in the figure. Supernatant was collected, and cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer. MCP-1 was measured in cell lysates, and MIP-2 was measured in supernatant by ELISA kit as described in materials and methods. Detected levels of MCP-1 and MIP-2 in the l-Hcy-treated groups were expressed as percentage of control. In a separate set of experiment, MCs were also treated with methionine (Met, 75 μM) and l-cysteine (Cys, 75 μM) for 48 h, and MCP-1 and MIP-2 were measured and expressed as percent control (inset). Data represents means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments, *P < 0.01 vs. control. B: Hcy-mediated attenuation of H2S was improved by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathione γ-lyase (CSE) gene delivery. MCs were treated with Met (75 μM), l-Cys (75 μM), and l-Hcy (75 μM, with or without CBS/CSE/double gene transfection) for 48 h, and the cell capabilities to generate H2S were measured by previously adopted method (39). Data represent means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.025 vs. control, #P < 0.05 vs. control. C: expression of CBS/CSE genes in MCs. MCs were transfected with pcDNA3.1/GFP, pcDNA3.1/CBS, pME18S-CSE-HA, or both CBS and CSE DNA as described (38). After 48 h, the transfection efficacy was determined by examining pcDNA/GFP-transfected cells for green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence using fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX51). Approximately 50% cells were found positive (original magnification, ×40). The CBS- and CSE-transfected cells had no fluorescence activity. Expression of CBS (D) and CSE (E) protein were determined by Western blot analysis.

To determine whether Hcy decreases generation of H2S in MCs, we incubated MCs with 75 μM of Hcy for 48 h and measured H2S generation in the cell homogenate. Hcy diminished H2S generation, whereas methionine and cysteine had no effect (Fig. 1B). To confirm that the decrease in H2S generation was attributable to Hcy, we repeated the experiment using MCs transfected with the genes encoding for the enzymes responsible for Hcy metabolism. As shown in Fig. 1B, MCs transfected with CBS, CSE, or both genes significantly enhanced MCs ability to produce H2S.

CBS and CSE genes transfected governed cysteine production during HHcy.

Hcy is an intermediate product in the pathway whereby methionine is metabolized to cysteine. This pathway is regulated by the activities of CBS and CSE. To determine whether CBS and CSE increase Cys production from Hcy in MCs, we measured Hcy and Cys in the cell culture medium before and after addition of Hcy. As shown in Table 1, Hcy was not detectable in the medium at baseline or at 48 h in either control or doubly transfected MCs. When exogenous Hcy was added to the medium of nontransfected cells, the concentration of Hcy in the medium remained the same at 48 h as at baseline; however, when Hcy was added to the medium of doubly transfected MCs, the concentration of Hcy significantly decreased in the medium after 48 h. The concentration of cysteine in the medium of nontransfected cells decreased by a similar amount over 48 h in the presence or absence of exogenous Hcy. In doubly transfected MCs, in contrast, the concentration of cysteine decreased by 89% in the absence of exogenous Hcy but only by 65% in the presence of Hcy. These findings suggest that the overexpression of CBS and CSE increase Hcy metabolism, resulting in increased cysteine production.

Table 1.

Overexpression of CBS and CSE metabolized Hcy and increased Cys concentration in Hcy-treated MCs

| Hcy Concentration, μM |

Cysteine Concentration, μM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | At 0 h | After 48 h | At 0 h | After 48 h |

| Control | ND | ND | 100.0 | 55.2 ± 4.32† |

| Control + l-Hcy (75 μM) | 75.0 | 77.4 ± 3.62 | 100.0 | 61.1 ± 5.10† |

| CBS+CSE | ND | ND | 100.0 | 11.2 ± 1.30* |

| CBS+CSE + l-Hcy (75 μM) | 75.0 | 13.7 ± 1.14† | 100.0 | 34.4 ± 3.12* |

Mesangial cells (MCs) were transfected with crystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and crystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) double genes as stated in materials and methods. Cells were treated without or with homocysteine (Hcy, 75 μM) for 48 h, and culture medium was processed for Hcy and cysteine (Cys) measurement by HPLC as described materials and methods. Appropriate controls were taken as shown in the table. Data are presented as means ± SE, n = 5 independent experiments,

Significant difference (P < 0.05);

P < 0.05 vs. 0 h. ND, not detectable.

Hcy-induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 were attenuated by CBS and CSE overexpression.

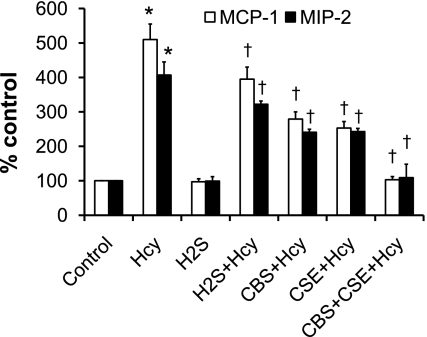

Multiple reports demonstrate that endogenous H2S is protective against inflammatory induction (18, 57). To determine whether overexpression of CBS and CSE prevent the appearance of markers of inflammation in MCs, we treated MCs doubly transfected with CBS and CSE with Hcy for 48 h and measured MCP-1 and MIP-2. Control cells received either vehicle, Hcy, H2S, or H2S + Hcy (Fig. 2). Hcy induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 in MCs, whereas simultaneous exogenous supplementation with H2S significantly reduced the expression of these inflammatory molecules (Fig. 2). Interestingly, overexpression of either CBS or CSE also significantly diminished MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression induced by Hcy (Fig. 2). MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression was even further reduced in the cells overexpressing both genes (Fig. 2). Vehicle or H2S alone had no effect on these two molecules expression.

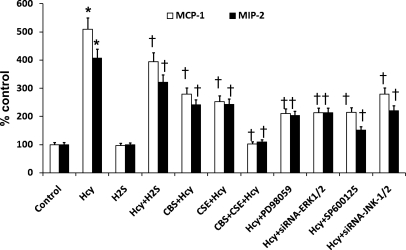

Fig. 2.

Increased ability of endogenous H2S production or exogenous supplementation attenuated Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction in MCs. MCs were transfected with CBS, CSE, or both cDNAs as described (38) or cultured without any transfection. Cells were treated with l-Hcy (75 μM) and supplemented with or without H2S (in the form of NaHS solution) in appropriate groups as shown in the figure. MCP-1 and MIP-2 were measured as described in the Fig. 1. Data represent means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.01 vs. control and †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy.

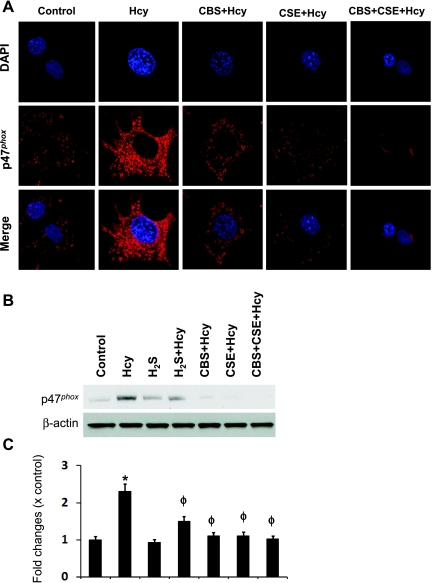

CBS and CSE gene therapy regulated p47phox expression in HHcy through H2S generation.

Hcy induces NAD(P)H oxidase, which is a predominant source of O2− generation and plays a vital role in Hcy-mediated oxidative damage (36, 51). To determine whether endogenous H2S has a regulatory role in NAD(P)H oxidase p47phox expression in HHcy, we incubated MCs transfected with CBS and CSE alone or in combination (double transfection), and with Hcy for 48 h followed by immunostaining with p47phox antibody. As shown in Fig. 3A, p47phox was upregulated in the MCs treated with Hcy. This induction was attenuated in both CBS and CSE transfected MCs. Interestingly, the expression of p47phox was completely abolished in the MCs transfected with these genes together (double transfection) (Fig. 3A). This result was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

CBS and CSE double gene therapy attenuated Hcy-induced p47phox upregulation in MCs. A: MCs were cultured in 8-well chamber slide and transiently transfected with CBS, CSE, or both the cDNAs and treated with Hcy (75 μM) for 48 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked with BSA in PBS, and immunostained with anti-p47phox antibody secondarily conjugated with Texas Red. Cells were also counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescence images were taken under laser scanning confocal microscope (Fluoview 1000, Olympus) and merged. Red fluorescence indicates p47phox expression. Representative images from four independent experiments were shown here. B: similar experiment was performed in 12-well plastic plates and expression of p47phox protein was determined by Western blot analysis. Blots reprobed with β-actin for loading control. C: bar diagram showing relative expression of p47phox normalized with β-actin loading control. Data represent means ± SE; n = 4. *P < 0.01 vs. control; ϕP < 0.05 vs. Hcy.

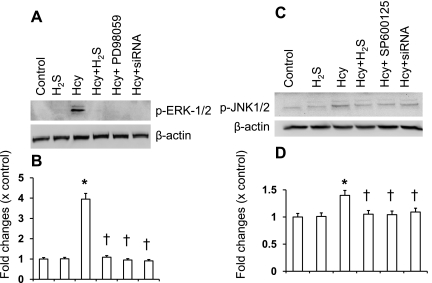

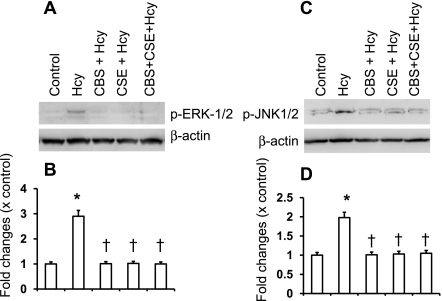

Hcy-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 was diminished by CBS and CSE.

Several laboratories have reported that Hcy exerts its effects through activation of ERK1/2 (30, 47) and JNK1/2 (25, 47) pathways. To determine whether H2S has any regulatory role in Hcy-mediated ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 induction, we compared the effect of H2S on Hcy-stimulated ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 in MCs, in the presence or absence of a pharmacological inhibitor of MEK1 (PD98059), a pharmacological inhibitor of JNK1/2 (SP600125), or in cells where expression of ERK1/2 or JNK1/2 was reduced by small interfering RNA (siRNA). As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, Hcy stimulated ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 activation in MCs as evidenced by increased expression of the phosphorylated forms. Hcy-stimulated ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 activation were blocked by H2S treatment (Fig. 4, A and B). Similar results were seen with pharmacological and siRNA blockers of these two signaling molecules (Fig. 4, A and B). Interestingly, CBS and CSE genes alone or double gene transfer inhibited phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 molecules induced by Hcy (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

H2S inhibited extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK1/2) phosphorylation induced by Hcy. A: ERK1/2 was either inhibited by small interferring RNA (siRNA) or blocked with pharmacological inhibitor (PD98059, 50 μM) or supplemented with H2S (30 μM, in the form of NaHS) and treated with Hcy (75 μM) for 30 min. Appropriate controls were taken. Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was detected by Western blot analysis. The blot reprobed with β-actin as loading control. B: bar diagram showed relative changes of phosphorylation over control (p-ERK1/2/β-actin). Data represent means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy treatment. C: in a similar set of experiments, JNK1/2 was either inhibited by siRNA or blocked with pharmacological inhibitor (SP600125, 10 μM) or supplemented with H2S (30 μM) and treated with Hcy (75 μM) for 30 min with appropriate controls. Phosphorylation of JNK1/2 was detected by Western blot analysis. Blot reprobed with β-actin as loading control. D: bar diagram showed the relative changes of phosphorylation over control (p-JNK1/2/β-actin). Data represents means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy treatment.

Fig. 5.

CBS and CSE double gene transfection attenuated Hcy-induced ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 phosphorylation in MCs. A: MCs were transfected with CBS, CSE, or both the genes, and after 48 h of transfection, cells were treated with Hcy (75 μM) for 30 min. Appropriate controls were taken. Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer, and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was detected by Western blot analysis. The blot reprobed with β-actin as loading control. B: bar diagram showed relative changes of ERK1/2 phosphorylation over control (p-ERK1/2/β-actin). Data represents means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy treatment. C: in a similar set of experiment, JNK1/2 phosphorylation was detected by Western blot analysis. Blots were reprobed with β-actin as loading control. D: bar diagram showed the relative changes of phosphorylation over control (p-JNK1/2/β-actin). Data represent means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy treatment.

Hcy-induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction were through ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 pathways.

To determine whether Hcy stimulates production of inflammatory molecules through ERK1/2- and JNK1/2-dependent pathways, we measured expression of MCP-1 and MIP-2 in MCs treated with or without Hcy and H2S (Fig. 6). To compare the effect of H2S supplementation and CBS and/or CSE overexpression on MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression, we overexpressed CBS, CSE, and doubly in MCs and treated with Hcy. To determine the involvement of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 in Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction, we used pharmacological and siRNA blockers of ERK and JNK as indicated in Fig. 6. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, Hcy-treated cells exhibited significantly decreased expression of MCP-1 and MIP-2 in the presence of H2S compared with MCs treated with Hcy alone (Fig. 6). The expression of these two molecules were further diminished in cells overexpressing either CBS or CSE. Interestingly, double-gene transfer completely inhibited and normalized expressions of MCP-1 and MIP-2 treated with Hcy (Fig. 6). Inhibition of ERK1/2 by siRNA or pharmacological MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 also significantly diminished expressions of these two molecules (Fig. 6). Similar effects were obtained by blocking JNK1/2 by siRNA or pharmacological blocker SP600125 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

CBS and CSE through H2S generation inhibited Hcy-induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction via ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 pathways. MCs were transfected with CBS, CSE, or double genes. In appropriate wells, as shown in the figure, ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 were inhibited by pharmacological blockers and treated with Hcy (75 μM) for 48 h. As showed in the figure, some wells also treated with Hcy (75 μM for 48 h) with or without H2S. At the end of experiments, supernatant was collected, and cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer. MCP-1 and MIP-2 were measured as described in materials and methods. Data represent means ± SE; n = 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.01 vs. control and †P < 0.05 vs. Hcy.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that HHcy decreases endogenous generation of H2S, which is a potent anti-inflammatory molecule, resulting in induction of MCP-1 and MIP-2 in MCs. Our study also demonstrates that overexpression of CBS and CSE accelerates Hcy metabolism, normalizes H2S generation, and attenuates MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression in MCs mediated by Hcy. This study thus highlights the importance of CBS and CSE in the regulation of HHcy and Hcy-mediated inflammatory induction.

There are multiple ways by which HHcy develops. These include: 1) methionine-rich diet; 2) vitamin B12/folate deficiency; 3) mutation or impairment of transsulfuration enzymes; and 4) renal impairment (35). None of these pathways are related to protein malnutrition and/or of cytokine-induced stressful disorders. A fifth mechanism of HHcy development has been reported in patients suffering from protein malnutrition and/or intestinal malabsorption characterized by insufficient N intake or assimilation, which also reduces body S accretion rates (19). This is an adaptive mechanism depressing the activity of CBS and allows accumulation of Hcy in biological fluids. Accumulated Hcy during this process in turn through remethylation maintain methionine homeostasis. HHcy in this regard considered as a consequence of cystathionase impairment and not as a causal factor (19, 49). However, if HHcy is due to pathways involving 1–4 reasons, as stated above, it could be both as a consequence and/or causal factor depending on the source. Our in vitro experiments were performed in a condition that does not mimic protein malnutrition or malabsorption, rather HHcy was created with excess Hcy supplementation. Therefore, we believe that HHcy in our model was a causal factor of cystathionase (CBS and/or CSE) impairment, as reported earlier (3, 36), resulting in H2S deficiency in the culture milieu.

HHcy has been reported in a number of CKD (10, 16) and implicated in the high frequency of vascular events in patients with CKD (52). This finding is somewhat paradoxical as Hcy undergoes metabolism to produce H2S, a well-known anti-inflammatory agent that would be expected to ameliorate vascular damage. The three enzymes responsible for the metabolism of Hcy to H2S are CBS, CSE, and 3-MST (12, 41–42, 48). Under pathological conditions, elevated levels of Hcy alter the transsulfuration pathway by inhibiting the CSE enzyme activity (3), which may further elevate Hcy in the body. This results in protein homocysteinylation and damage (21) manifested as loss of function. For example, Jakubowski (21) reported that homocysteinylation of methionyl-tRNA synthetase and trypsin causes inactivation of these protein molecules. We speculate that high Hcy may inactivate H2S-generating enzymes in the body, including CBS, CSE, and/or 3-MST, which metabolize Hcy. Together these may reduce endogenous production of H2S. In the present study, we have demonstrated reduced production of endogenous H2S in MCs exposed to high ambient concentrations of Hcy (Fig. 1B), which can be overcome by overexpression of CBS and CSE (Fig. 1B).

Our observation that CBS/CSE overexpression results in higher production of H2S, faster clearance of Hcy, and improvement or even restoration of HHcy-mediated molecular lesions suggest new avenues for therapy of HHcy and associated vascular complications. Although it is reported that at elevated level, Hcy competes with cysteine (Cys) in binding to cystathionase (35, 43), and thus, HHcy decreases H2S production through substrate inhibition (3); however, in this study we did not measure binding capacity of Hcy and Cys to cystathionase. Rather CBS and CSE genes were overexpressed in MCs and these MCs were incubated with high levels of Hcy in the culture milieu. It is worthy to mention that CBS and CSE enzymes belong to the transsulfuration cascade and govern the production of Cys and glutathione along the desulfuration pathway (45). The likely hypothesis of our study was that addition of CBS/CSE genes to the incubation milieu will stimulate the production of Cys from Hcy (as we treated cells with Hcy) and that the supply of Cys could in turn operate as a reductant molecule that able to convert elemental sulfur (S8) into H2S. Interestingly, the above hypothesis is tested and validated by the simultaneous measurement of Hcy and Cys in the culture media just before and after the overexpression of CBS/CSE (Table 1), where CBS/CSE enzyme promotes Cys production from Hcy. This result implies that the beneficial effects of CBS/CSE are not directly induced but are rather mediated by overproduction of Cys.

It is reported that high circulating concentrations of the inflammatory markers IL-1ra and IL-6 were significantly correlated with HHcy and associated with atherosclerosis in older populations (14). Recent studies have demonstrated that Hcy induces MCP-1 (4) and MIP-2 (40) in MCs and that the induction of these inflammatory markers is linked to adverse outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and CKD. The current study confirms Hcy induction of MCP-1 and MIP-2 in mouse MCs (Fig. 1A) and shows that this induction is due, in part, to downregulation of endogenous H2S production (Fig. 1B). Although H2S supplementation alone reduced Hcy-mediated induction of inflammatory molecules, further reduction occurred when CBS or CSE were overexpressed (Fig. 2) due to increased cellular ability to generate H2S (Fig. 1B). These results suggest an alternative approach to combat Hcy-associated inflammation in CKD.

Multiple laboratories including our own have reported that Hcy stimulates O2− generation through a NAD(P)H-mediated mechanism (8, 9, 34, 55). We have previously reported that mice with HHcy expressed higher level of p47phox subunit of NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney cortical tissue compared with mouse with normal Hcy level, and H2S supplementation normalized p47phox expression (36). Similarly, upregulated p47phox expression in Hcy-treated mouse MCs was diminished by H2S treatment (36). Others have reported that inhibition of p22phox by siRNA transfection normalized Hcy-induced O2− production in human endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells (9). The present study supports our previous findings and suggests the possibility of gene-based therapy as a mechanism to enhance endogenous H2S production and reduce O2− production (through reduced oxidative p47phox, Fig. 3, A and B) induced by HHcy.

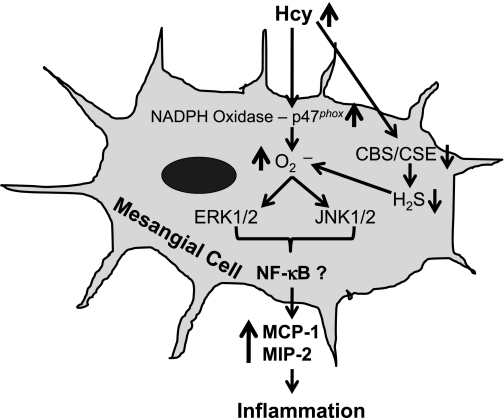

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are reported to regulate several biological responses, including mesangial proliferation (5, 20), migration (7), and inflammation (24). Of particular interests, the involvement of two important MAPKs ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 pathways in mediating inflammation was reported by several laboratories. Recent reports also suggest that Hcy stimulated MCP-1 expression in rat MCs via nuclear factor-κB (4), and MIP-2 production via phosphoinositol trisphosphate kinase- and p38MAPK-dependent pathways (40); however, none of these studies were focused to investigate whether ERK-1/2 and JNK-1/2 are involved in Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression in MCs. Therefore, we determined whether these two signaling pathways are involved in Hcy-induced MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction and possible regulatory role of H2S in these pathways. Our results suggested that Hcy induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2, and H2S supplementation attenuated these activations (Fig. 4). Interestingly, CBS or CSE overexpression also inhibited ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 phosphorylation in MCs induced by Hcy (Fig. 5), which confirms the regulatory role of H2S in these signaling cascades. Furthermore, the expressions of MCP-1 and MIP-2 were, at least in part, mediated by ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 pathways (Fig. 6). In a report, although Ingram et al. (20) demonstrated that Hcy-induced ERK1/2 signaling mechanism was involved in MCs proliferation and endoplasmic reticulum stress, to our knowledge, our study is the first to report the involvement of these two cascades in Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression in MCs. The novelty of the present study is that CBS and CSE overexpression blocks these two pathways through generation of H2S in HHcy and ameliorate inflammation. An overall hypothesis and possible mechanism of Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 induction is depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Schematic of homocysteine-mediated signaling pathways leading to MCP-1 and MIP-2 expressions in mouse MCs. Hcy activates NADPH oxidase p47phox subunit resulting in increased generation of O2·− (superoxide), which phosphorylates ERK1/2 and JNK1/2. Activation of these signaling cascades induces MCP-1 and MIP-2 expressions. Hcy also competitively inhibit CBS/CSE enzymes leading to decrease endogenous generation of H2S. H2S is an antioxidant, and its reduction results further increase of oxidative stress that amplify Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression. CBS/CSE gene delivery enhances cellular ability to produce H2S from Hcy and attenuates Hcy-mediated MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression resulting in amelioration of inflammatory response in MCs.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Hcy induced inflammatory molecules MCP-1 and MIP-2, in part, through upregulation of NAD(P)H p47phox subunit and downregulation of MCs' capability to generate H2S through ERK1/2- and JNK1/2-dependent pathways. Supplementation of H2S or either CBS or CSE gene delivery normalized p47phox expression and enhanced cellular capability to generate endogenous H2S, which partially inhibited MCP-1 and MIP-2 expression induced by Hcy. CBS and CSE double gene delivery was, however, more effective than H2S supplementation or single gene transfer. Together, these results may partially explain inflammatory mechanisms associated with HHcy in CKD, and reveals that CBS/CSE-dependent H2S generation play major role in this process.

GRANTS

This study was supported, in part, by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-71010, NS-51568, and HL-88012. E. D. Lederer was supported by the VA Merit Review Board.

DISCLOSURES

The views articulated in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Abe K, Watanabe Y, Saito H. Differential role of nitric oxide in long-term potentiation in the medial and lateral amygdala. Eur J Pharmacol 297: 43–46, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bos EM, Leuvenink HG, Snijder PM, Kloosterhuis NJ, Hillebrands JL, Leemans JC, Florquin S, van Goor H. Hydrogen sulfide-induced hypometabolism prevents renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1901–1905, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chang L, Geng B, Yu F, Zhao J, Jiang H, Du J, Tang C. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits myocardial injury induced by homocysteine in rats. Amino Acids 34: 573–585, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheung GT, Siow YL, OK Homocysteine stimulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in mesangial cells via NF-kappaB activation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 86: 88–96, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choudhury GG, Karamitsos C, Hernandez J, Gentilini A, Bardgette J, Abboud HE. PI-3-kinase and MAPK regulate mesangial cell proliferation and migration in response to PDGF. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F931–F938, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clarke R, Collins R, Lewington S, Phil D, Donald A, Alfthan G, Tuomilehto J, Arnesen E, Bonaa K, Blacher J, Boers GHJ, Bostom A, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Brattström L, Breteler MMB, Hofman A, Chambers JC, Kooner JS, Coull BM, Evans RW, Kuller LH, Evers S, Folsom AR, Freyburger G, Parrot F, Genest J, Jr, Dalery K, Graham IM, Daly L, Hoogeveen EK, Kostense PJ, Stehouwer CDA, Hopkins PN, Jacques P, Selhub J, Luft FC, Jungers P, Lindgren A, Lolin YI, Loehrer F, Fowler B, Mansoor MA, Malinow MR, Ducimetiere P, Nygard O, Refsum H, Vollset SE, Ueland PM, Omenn GS, Beresford SAA, Roseman JM, Parving HH, Gall MA, Perry IJ, Ebrahim SB, Shaper AG, Robinson K, Jacobsen DW, Schwartz SM, Siscovick DS, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH, Feskens EJM, Kromhout D, Ubbink J, Elwood P, Pickering J, Verhoef P, von Eckardstein A, Schulte H, Assmann G, Wald N, Law MR, Whincup PH, Wilcken DEL, Sherliker P, Linksted P, Smith GD. Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA 288: 2015–2022, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crean JK, Finlay D, Murphy M, Moss C, Godson C, Martin F, Brady HR. The role of p42/44 MAPK and protein kinase B in connective tissue growth factor induced extracellular matrix protein production, cell migration, and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement in human mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 277: 44187–44194, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dong F, Zhang X, Li SY, Zhang Z, Ren Q, Culver B, Ren J. Possible involvement of NADPH oxidase and JNK in homocysteine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Toxicol 5: 9–20, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edirimanne VE, Woo CW, Siow YL, Pierce GN, Xie JY, OK Homocysteine stimulates NADPH oxidase-mediated superoxide production leading to endothelial dysfunction in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 85: 1236–1247, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Francis ME, Eggers PW, Hostetter TH, Briggs JP. Association between serum homocysteine and markers of impaired kidney function in adults in the United States. Kidney Int 66: 303–312, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukagawa NK, Minaker KL, Young VR, Rowe JW. Insulin dose-dependent reductions in plasma amino acids in man. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 250: E13–E17, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geng B, Yang J, Qi Y, Zhao J, Pang Y, Du J, Tang C. H2S generated by heart in rat and its effects on cardiac function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313: 362–368, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goebel U, Siepe M, Schwer CI, Schibilsky D, Foerster K, Neumann J, Wiech T, Priebe HJ, Schlensak C, Loop T. Inhaled carbon monoxide prevents acute kidney injury in pigs after cardiopulmonary bypass by inducing a heat shock response. Anesth Analg 111: 29–37, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gori AM, Corsi AM, Fedi S, Gazzini A, Sofi F, Bartali B, Bandinelli S, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Ferrucci L. A proinflammatory state is associated with hyperhomocysteinemia in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr 82: 335–341, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heinz J, Kropf S, Domrose U, Westphal S, Borucki K, Luley C, Neumann KH, Dierkes J. B vitamins and the risk of total mortality and cardiovascular disease in end-stage renal disease: results of a randomized controlled trial. Circulation 121: 1432–1438, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herrmann W, Schorr H, Obeid R, Makowski J, Fowler B, Kuhlmann MK. Disturbed homocysteine and methionine cycle intermediates S-adenosylhomocysteine and S-adenosylmethionine are related to degree of renal insufficiency in type 2 diabetes. Clin Chem 51: 891–897, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237: 527–531, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu LF, Wong PT, Moore PK, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in microglia. J Neurochem 100: 1121–1128, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ingenbleek Y. Hyperhomocysteinemia is a biomarker of sulfur-deficiency in human morbidities. Open Clin Chem J 2: 49–60, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ingram AJ, Krepinsky JC, James L, Austin RC, Tang D, Salapatek AM, Thai K, Scholey JW. Activation of mesangial cell MAPK in response to homocysteine. Kidney Int 66: 733–745, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jakubowski H. Protein homocysteinylation: possible mechanism underlying pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. FASEB J 13: 2277–2283, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide: its production, release and functions. Amino Acids 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Labarrere CA, Zaloga GP. C-reactive protein: from innocent bystander to pivotal mediator of atherosclerosis. Am J Med 117: 499–507, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leung JC, Tang SC, Chan LY, Chan WL, Lai KN. Synthesis of TNF-alpha by mesangial cells cultured with polymeric anionic IgA–role of MAPK and NF-kappaB. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 72–81, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levrand S, Pacher P, Pesse B, Rolli J, Feihl F, Waeber B, Liaudet L. Homocysteine induces cell death in H9C2 cardiomyocytes through the generation of peroxynitrite. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359: 445–450, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li L, Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Lee LC, Del Soldato P, Moore PK. Anti-inflammatory and gastrointestinal effects of a novel diclofenac derivative. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 706–719, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loscalzo J. Homocysteine trials–clear outcomes for complex reasons. N Engl J Med 354: 1629–1632, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mak RH, Cheung W, Cone RD, Marks DL. Leptin and inflammation-associated cachexia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 69: 794–797, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malinow MR, Kang SS, Taylor LM, Wong PW, Coull B, Inahara T, Mukerjee D, Sexton G, Upson B. Prevalence of hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Circulation 79: 1180–1188, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moshal KS, Sen U, Tyagi N, Henderson B, Steed M, Ovechkin AV, Tyagi SC. Regulation of homocysteine-induced MMP-9 by ERK1/2 pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C883–C891, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muntner P, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Chen J, Whelton PK, He J. The prevalence of nontraditional risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 140: 9–17, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oberg BP, McMenamin E, Lucas FL, McMonagle E, Morrow J, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J. Increased prevalence of oxidant stress and inflammation in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 65: 1009–1016, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodriguez WE, Sen U, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Carneal G, Aggrawal D, Newsome J, Tyagi SC. PPAR gamma agonist normalizes glomerular filtration rate, tissue levels of homocysteine, and attenuates endothelial-myocyte uncoupling in alloxan induced diabetic mice. Int J Biol Sci 4: 236–244, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sen U, Basu P, Abe OA, Givvimani S, Tyagi N, Metreveli N, Shah KS, Passmore JC, Tyagi SC. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates hyperhomocysteinemia-associated chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F410–F419, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sen U, Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine to hydrogen sulfide or hypertension. Cell Biochem Biophys 57: 49–58, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sen U, Munjal C, Qipshidze N, Abe O, Gargoum R, Tyagi SC. Hydrogen sulfide regulates homocysteine-mediated glomerulosclerosis. Am J Nephrol 31: 442–455, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sen U, Rodriguez WE, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Kundu S, Tyagi SC. Ciglitazone, a PPARgamma agonist, ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in part through homocysteine clearance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1205–E1212, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sen U, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Moshal KS, Rodriguez WE, Tyagi SC. Cystathionine-βsynthase gene transfer and 3-deazaadenosine ameliorate inflammatory response in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1779–C1787, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sen U, Vacek TP, Hughes WM, Kumar M, Moshal KS, Tyagi N, Metreveli N, Hayden MR, Tyagi SC. Cardioprotective role of sodium thiosulfate on chronic heart failure by modulating endogenous H2S generation. Pharmacology 82: 201–213, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shastry S, James LR. Homocysteine-induced macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production by glomerular mesangial cells is mediated by PI3 Kinase and p38 MAPK. J Inflamm 6: 27, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem (Tokyo) 146: 623–626, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 703–714, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh S, Padovani D, Leslie RA, Chiku T, Banerjee R. Relative contributions of cystathionine beta-synthase and gamma-cystathionase to H2S biogenesis via alternative trans-sulfuration reactions. J Biol Chem 284: 22457–22466, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stenvinkel P. New insights on inflammation in chronic kidney disease-genetic and non-genetic factors. Nephrol Ther 2: 111–119, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stipanuk MH, Ueki I. Dealing with methionine/homocysteine sulfur: cysteine metabolism to taurine and inorganic sulfur. J Inherit Metab Dis 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stott DJ, MacIntosh G, Lowe GD, Rumley A, McMahon AD, Langhorne P, Tait RC, O'Reilly DS, Spilg EG, MacDonald JB, MacFarlane PW, Westendorp RG. Randomized controlled trial of homocysteine-lowering vitamin treatment in elderly patients with vascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 82: 1320–1326, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sung ML, Wu CC, Chang HI, Yen CK, Chen HJ, Cheng JC, Chien S, Chen CN. Shear stress inhibits homocysteine-induced stromal cell-derived factor-1 expression in endothelial cells. Circ Res 105: 755–763, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Swaroop M, Bradley K, Ohura T, Tahara T, Roper MD, Rosenberg LE, Kraus JP. Rat cystathionine beta-synthase. Gene organization and alternative splicing. J Biol Chem 267: 11455–11461, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tang B, Mustafa A, Gupta S, Melnyk S, James SJ, Kruger WD. Methionine-deficient diet induces post-transcriptional downregulation of cystathionine beta-synthase. Nutrition 26: 1170–1175, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Taub JW, Huang X, Ge Y, Dutcher JA, Stout ML, Mohammad RM, Ravindranath Y, Matherly LH. Cystathionine-beta-synthase cDNA transfection alters the sensitivity and metabolism of 1-beta-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine in CCRF-CEM leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo: a model of leukemia in Down syndrome. Cancer Res 60: 6421–6426, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Edwards JG, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Kaley G, Koller A. Increased superoxide production in coronary arteries in hyperhomocysteinemia: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, NAD(P)H oxidase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 418–424, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Guldener C. Homocysteine and the kidney. Curr Drug Metab 6: 23–26, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Guldener C. Why is homocysteine elevated in renal failure and what can be expected from homocysteine-lowering? Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1161–1166, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vollset SE, Refsum H, Tverdal A, Nygard O, Nordrehaug JE, Tell GS, Ueland PM. Plasma total homocysteine and cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Clin Nutr 74: 130–136, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yi F, Jin S, Zhang F, Xia M, Bao JX, Hu J, Poklis JL, Li PL. Formation of lipid raft redox signalling platforms in glomerular endothelial cells: an early event of homocysteine-induced glomerular injury. J Cell Mol Med 13: 3303–3314, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yi F, Zhang AY, Li N, Muh RW, Fillet M, Renert AF, Li PL. Inhibition of ceramide-redox signaling pathway blocks glomerular injury in hyperhomocysteinemic rats. Kidney Int 70: 88–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zanardo RC, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J 20: 2118–2120, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]