Abstract

Through their ion-pumping and non-ion-pumping functions, Na+-K+-ATPase protein complexes at the plasma membrane are critical to intracellular homeostasis and to the physiological and pharmacological actions of cardiotonic steroids. Alteration of the abundance of Na+-K+-ATPase units at the cell surface is one of the mechanisms for Na+-K+-ATPase regulation in health and diseases that has been closely examined over the past few decades. We here summarize these findings, with emphasis on studies that explicitly tested the involvement of defined regions or residues on the Na+-K+-ATPase α1 polypeptide. We also report new findings on the effect of manipulating Na+-K+-ATPase membrane abundance by targeting one of these defined regions: a dileucine motif of the form [D/E]XXXL[L/I]. In this study, opossum kidney cells stably expressing rat α1 Na+-K+-ATPase or a mutant where the motif was disrupted (α1-L499V) were exposed to 30 min of substrate/coverslip-induced-ischemia followed by reperfusion (I-R). Biotinylation studies suggested that I-R itself acted as an inducer of Na+-K+-ATPase internalization and that surface expression of the mutant was higher than the native Na+-K+-ATPase before and after ischemia. Annexin V/propidium iodide staining and lactate dehydrogenase release suggested that I-R injury was reduced in α1-L499V-expressing cells compared with α1-expressing cells. Hence, modulation of Na+-K+-ATPase cell surface abundance through structural determinants on the α-subunit is an important mechanism of regulation of cellular Na+-K+-ATPase in various physiological and pathophysiological conditions, with a significant impact on cell survival in face of an ischemic stress.

Keywords: dileucine motif, ischemia-reperfusion injury, oppossum kidney cells, cardiotonic steroids

the na+-k+-atpase is the membrane-spanning enzyme that both establishes and maintains the electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane of animal cells by coupling the hydrolysis of ATP to the transport of Na+ and K+ (23, 43). The Na+-K+-ATPase complex consists of two dissimilar α- and β-subunits, which exist as multiple isoforms. The α-subunit is the primary contributor to overall catalysis and contains the binding sites for the substrates required by the enzyme. Expression of the α1-isoform is apparently ubiquitous, while the three others (α2–4) have increasingly restricted expression patterns (5, 6). Three distinct isoforms of the β-subunit, which is critical to the structural and functional maturation of Na+-K+-ATPase and regulates its transport properties, have been identified (21). In addition, several members of the FXYD family of accessory proteins have been shown to bind to and regulate Na+-K+-ATPase function in a tissue-specific manner (19, 20).

The Na+-K+-ATPase is also the pharmacological target of endogenous and exogenous cardiotonic steroids (CTS). CTS have long been known as potent inhibitors of Na+-K+-ATPase ion-pumping function, which is critical to their effect on Na+-coupled influx of ions, amino acids, or glucose. This inhibitory action on Na+-K+-ATPase ion-pumping function and subsequent modulation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchange has been extensively studied in the cardiac positive inotropic action of CTS. In addition, CTS such as ouabain, digoxin, or marinobufogenin, initiate intracellular signaling cascades via stimulation of the Na+-K+-ATPase receptor function (30, 36, 47, 48). The role of this more recently discovered property in the hormone-like function of endogenous CTS and in the therapeutic effect of exogenous CTS in health and diseases is being increasingly recognized. Progress in the understanding of CTS action in the cardiovascular and nervous systems, metabolism, or cell growth and differentiation has been emphasized in recent reviews (1, 2, 40, 42).

Regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase Cell Surface Abundance and Known Structural Determinants on the Na+-K+-ATPase α1 Polypeptide

Localization of Na+-K+-ATPase at the cell surface is important to both ion-pumping and receptor functions, and modulation of cellular Na+-K+-ATPase activity through changes in cell surface expression has been reported in response to major physiological or pathophysiological stimuli. Such stimuli include CTS themselves (32, 45), the parathyroid hormone (24), dopamine (4), insulin (3, 12, 18), hypoxia (14), and hypercapnia (46). Over the past 15 years, investigations using heterologous expression systems have focused on the identification of key structural determinants along the Na+-K+-ATPase α1 polypeptide that influence its expression at the cell surface under basal conditions or in response to specific stimuli. Data from such studies are compiled in Table 1. We have recently examined one of these molecular determinants, a dileucine-based motif for recognition by clathrin-coated vesicle (CCV) adaptor proteins of the structure n(p)2–4LL, where n is a negatively charged residue and p is a polar residue (26). The sequence is well conserved among all the known mammalian α1 sequences (Table 2), and our studies revealed that mutations targeting this motif such as L499V or E495S resulted in an increased abundance of Na+-K+-ATPase α1-units at the cell surface (44).

Table 1.

Summary of domains and sites of posttranslational modifications involved in the regulation of rat Na+-K+-ATPase α1 surface expression

| Structural Determinant | Trigger/Signal Cascade | α1 Surface Expression | Ref. No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine-based domain for AP-binding | ANG II/AT1/AP1 | Up | 17 |

| IVVY-255 | |||

| Tyrosine-based domain for AP-binding | Dopamine/DR1/AP2 | Down | 9, 13 |

| 537-YLEL | Hypoxia | ||

| Dileucine-based motif for AP-binding | None | Up | 44 |

| EPKHL-499L | |||

| Phosphorylation /S-18 | Dopamine | Down | 10 |

| Phosphorylation /S-18 | Hypoxia/PKC | Down | 14 |

| Phosphorylation /S-11 | PTH/PKC/ERK/CCV | Down | 24 |

| Ubiquitination/K-16/K-17/K-19/K-20 | Hypoxia/ubiquitination | Down | 15 |

| Proline-rich domain TPPPTTP-87 | Dopamine | Down | 49 |

ANG II, angiotensin II; AT1, Type 1 angiotensin II receptor; AP1 and AP2, clathrin adaptor protein 1 and 2; DR1, dopamine receptor 1; PKC, protein kinase C; PTH, parathyroid hormone; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; CCV, clathrin-coated vesicle.

Table 2.

Conserved dileucine motif of the form [D/E]XXXL[L/I] motif in Na+-K+-ATPase α1 sequences in various species

| Species | NCBI Access No. | [D/E]XXXL[L/I] Motif |

|---|---|---|

| Rattus norvegicus (rat) | NM_012504 | SIHK489NPNASEPKHL499LVMK |

| Homo sapiens (human) | NM_000701 | SIHK489NPNASEPKHL499LVMK |

| Dario rerio (zebrafish) | NM_131686 | SIHQ492NPNSNNTESKHL504LVMK |

| Ovis aries (sheep) | NM_001009360 | SIHK487NANAGEPRHL497LVMK |

| Mus musculus (mouse) | NM_144900 | SIHK489NPNASEPKHL499LVMK |

| Sus scrofa (pig) | NM_214249 | SIHK487NPNTAEPRHL497LVMK |

| Bos taurus (cattle) | BC123864 | SIHK487NANAGEPRHL497LVMK |

| Canis familiaris (dog) | NM_001003306 | SIHK487NPNTSEPRHL497LVMK |

| Gallus gallus (chicken) | NM_205521 | SIHK487NANAGESRHL497LVMK |

The conserved sequence of amino acid residues that form the dileucine motif appears in boldface.

Using a Na+-K+-ATPase α1 Structural Determinant of Surface Abundance as a Target for Protection Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

We reckoned that an increased abundance of Na+-K+-ATPase pump units at the cell surface could be salutary to cells with critically high levels of intracellular Na+ such as those reported during ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury and may result in protection against I-R-induced cell death (34, 35). This hypothesis was tested in opossum kidney (OK) cells stably expressing native or L499V-mutated forms of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 polypeptide exposed to substrate/coverslip-induced I-R.

METHODS

Cell Lines

OK cells stably expressing native and L499V-mutated forms of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 were used. Details on the experimental procedures related to expression vectors and site-directed mutagenesis, heterologous expression, and initial characterization of Na+-K+-ATPase enzyme properties in these cells can be found in Sottejeau et al. (44).

Substrate and Coverslip-Induced Ischemia-Reperfusion

Ischemia was induced by removal of the substrate and placement of a glass coverslip over a portion of the OK cell monolayers, as described previously (38). Briefly, 70% confluent OK cells grown in 100-mm dishes were rinsed once with PBS and incubated in Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer containing (in mmol/l) 118.0 NaCl, 4.0 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.3 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 0.3 EGTA, 25 NaHCO3, and 37 d-glucose for 20 min at 37°C. Ischemia was then simulated by replacing the KH buffer by PBS and placing two 22 × 44 mm LifterSlips and one 22 × 63 mm LifterSlip (Thermo scientific) over the cell monolayers for 30 min at 37°C. Reperfusion was initiated by gentle removal of the LifterSlips and returned to KH buffer at 37°C. For confocal imaging studies, OK cells were grown on square coverslip 22 × 22 mm (Fisher) in six-well plates, and I-R was induced as described above using 18-mm diameter round glass coverslips (Fisher).

Annexin V/Propidium Iodide Staining

At the end of the experimental protocol, OK cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature after a wash in PBS 1×. Cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V and red fluorescent propidium iodide (PI) (Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kit no. 2, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The coverslips were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen). Confocal images were captured by sequential scanning with no overlap using a Leica TCS SP5 broadband confocal microscope system coupled to a DMI 6000CS inverted microscope equipped with multiple continuous wave lasers and a ×63/1.3 oil objective.

Measurement of Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity

At the end of a 60-min long reperfusion period, the cell incubation buffer was collected and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was determined colorimetrically using a standard assay (Cytotoxicity Detection Kit, Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer recommendations.

Assessment of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 Total Protein Abundance and Surface Expression

Total abundance of the introduced rat α1 constructs was determined by electrophoresis and immunoblotting of proteins from cell lysates using anti-NASE antibody as described (44). For total expression, equal loading of the samples among the lanes of the gel was confirmed by probing with a commercial antibody against actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Introduced α1 expressed at the cell surface was detected by biotinylation following the recommended procedures of Gottardi et al. (22), as we have recently reported in detail (44). I-R-induced endocytosis of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 units was tested with a pulse–chase strategy as slightly modified from previous studies (27, 44). Briefly, proteins expressed at the cell surface were first biotinylated as described above, quenched with PBS–glycine buffer, and rinsed twice with saline solution. The cells were then incubated in DMEM medium for 20 min at 37°C in 10% CO2 followed by 30 min of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion. The remaining surface-bound biotin was then cleaved by treatment with 50 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) reducing agent for 15 min at 4°C.

Immunocytochemistry and Fluorescence Imaging

At the end of the experimental protocol, cells were fixed by 20 min incubation with ice-cold methanol, washed with PBS, and blocked with Signal Enhancer (Invitrogen). The cells were then incubated with a mouse anti-Na+-K+-ATPase α1 monoclonal antibody (clone C464.6, Upstate) in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, cells were exposed to AlexaFluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature, washed, and mounted onto slides. Image visualization was performed using a Leica TCS SP5 broadband confocal microscope system coupled to a DMI 6000CS inverted microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Decreased Post-I-R Cell Death in Cells Expressing the Na+-K+-ATPase α1-L499V Mutant

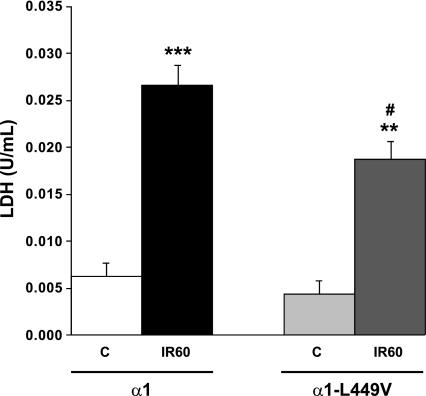

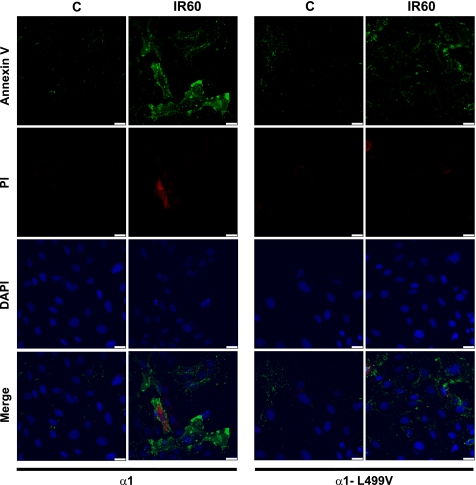

In vitro I-R was induced in OK cells by removing the metabolic substrates from the culture medium and by placing coverslips over the monolayer, according to the protocol of Pitts and Tombs (38). Whereas all cells were exposed to substrate depletion for 30 min, it is important to note that the three LifterSlips represented about 57% of the surface of the 100-mm diameter dishes and hence did not cover the entire monolayer. As shown in Fig. 1, this resulted in a significant increase in LDH release in the media over the course of 60 min of reperfusion (IR60), indicative of cell injury. The LDH release by α1-expressing cells was comparable to that observed in nontransfected OK cells (not shown) but was significantly higher than the release measured in α1-L499V-expressing cells exposed to the same I-R protocol. To further assess the I-R-induced decreased cell viability and the comparatively lower injury observed in the α1-L499V-expressing group, cells grown on coverslips were exposed to control and I-R conditions as detailed in methods and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V to label apoptotic cells and red-fluorescent PI to label late apoptotic/necrotic cells. The representative pictures shown in Fig. 2 present qualitative evidence that 30 min of substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia followed by 60 min of reperfusion resulted in an increase in the annexin V+ population in α1-expressing cells that was more pronounced than the increase produced in α1-L499V-expressing cells. A few PI+ cells defined as cells with nuclear PI signal [i.e., overlapping with DAPI fluorescence, which excludes potential “false-positive” with cytoplasmic PI signal only (41)] were detected after I-R. Specifically, 4 PI+ cells per 100 cells were detected in the α1-group after I-R, and 1 PI+ cell per 100 cells was detected in the α1-L499V-expressing group.

Fig. 1.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released by α1- and α1-L499V-expressing opossum kidney (OK) cells exposed to ischemia followed by reperfusion. LDH release was measured as an index of cell injury in the media of α1- and α1-L499V-expressing cells after 110 min Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer (C, control, n = 6) or after 20 min KH/30 min substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia/60 min KH (IR60: ischemia-reperfusion 60, n = 6). Values are expressed as means ± SE. ***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01 vs. respective controls; and #P < 0.05 vs. IR60 α1.

Fig. 2.

Annexin V/propidium iodide (IP) staining in Na+-K+-ATPase α1- and α1-L499V-expressing OK cells exposed to ischemia followed by reperfusion. After treatment, fluorescent staining of Annexin V (green), PI (red), and DAPI (blue) was performed as described in methods, and cells were examined by fluorescence confocal microscopy. C, control (110 min KH); IR60, 20 min KH/30 min substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia/60 min KH. Pictures are representative of at least 10 fields observed in 3 different preparations for each condition in Na+-K+-ATPase α1- and α1-L499V-expressing OK cells. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Increased Post-I-R Surface Abundance in Cells Expressing the Na+-K+-ATPase α1L499V Mutant

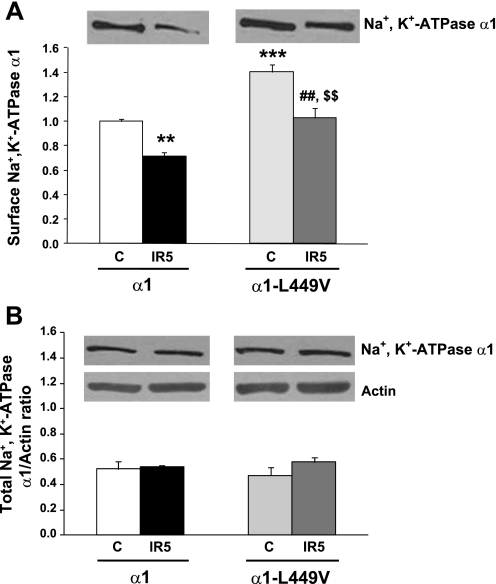

With the use of biotinylation techniques, Na+-K+-ATPase surface expression was compared in OK cells stably expressing native and L499V Na+-K+-ATPase α1 with or without exposure to 30 min ischemia and 5 min reperfusion (IR5). The data presented in Fig. 3 confirmed our previously reported finding that basal surface expression of Na+-K+-ATPase α1-units is significantly higher in the mutant group without change in total expression (44). After 5 min of reperfusion, total expression of Na+-K+-ATPase α1-was unchanged (3B), but its surface expression was significantly decreased in both α1- and α1-L499V Na+-K+-ATPase-expressing cells compared with their respective controls. The I-R-induced decrease was about 25–30% for both groups. As a result, the post-I-R surface expression in the α1-L499V-expressing cells was comparable to the pre-I-R level in the α1-expressing group.

Fig. 3.

Surface and total expression of Na+-K+-ATPase units in α1- and α1-L499V-expressing OK cells exposed to 30 min of substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia followed by 5 min of reperfusion. A: surface expression. Top, typical immunoblot of biotinylated membrane proteins recovered by affinity purification with streptavidin. Bottom, pooled data relative to basal expression of wild-type α1 represented as means ± SE (n = 8–10). *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control α1; ##P < 0.01 vs. C α1-L499V, and $$P < 0.01 vs. IR5 α1. B: total expression. Top, typical immunoblots of cell lysates probed with antibodies specific for rat α1 and actin. Bottom, pooled data relative to basal expression of wild-type α1, represented as means ± SE (n = 8–10). No significant difference was found. IR5, exposed to 30 min coverslip-induced ischemia followed by 5 min of reperfusion.

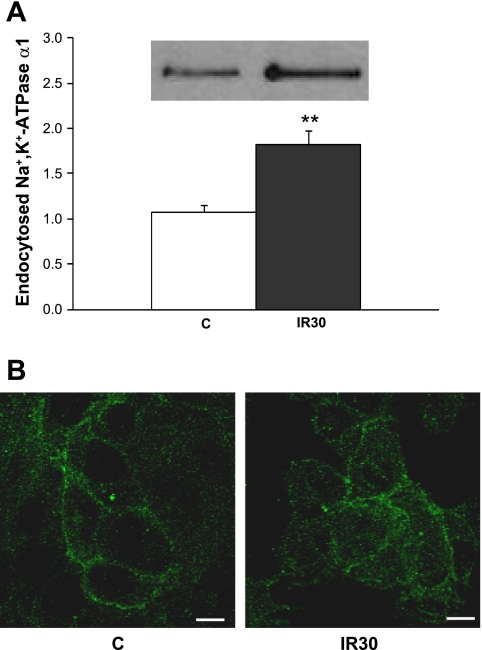

I-R Induces Internalization of Na+-K+-ATPase Units

The data collected from the biotinylation studies presented in Fig. 3 suggested that I-R results in decreased abundance of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 units at the cell surface. To test whether this was due to an increased internalization of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 units during I-R, we compared Na+-K+-ATPase removal from the cell surface using a cell surface biotinylation and TCEP treatment (see methods) in α1-expressing cells in control conditions (80 min pulse-chase aerobic buffer) or exposed to the IR30 protocol (20 min aerobic buffer, 30 min substrate/coverslip ischemia, 30 min aerobic buffer). As shown in Fig. 4A, the amount of Na+-K+-ATPase internalized in 80 min was significantly increased in the IR30 group compared with the control (P < 0.01). Immunofluorescent labeling of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 units before and after I-R was consistent with increased intracellular signal after 30 min of reperfusion (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Internalization of Na+-K+-ATPase units in cells exposed to 30 min of substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion. After treatment, assessment of the amount of endocytosed Na+-K+-ATPase α1 units and immunofluorescent staining of Na+-K+-ATPase α1 were performed as described in methods. A: endocytosed Na+-K+-ATPase. Inset, typical immunoblot of biotinylated endocytosed Na+-K+-ATPase α1 recovered by affinity purification with streptavidin. Graph depicts the pooled data relative to control represented as means ± SE (n = 4). **P < 0.01 vs. control. B: pictures are representative of 6 independent experiments for each condition. C, control (60 min without ischemia); IR30, 30 min substrate/coverslip-induced ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion. Scale bar = 10 μM.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we review the growing list of physiological and pathological regulators of Na+-K+-ATPase surface abundance with emphasis on studies that explicitly tested the involvement of defined regions or residues on the Na+-K+-ATPase α1 polypeptide. We also report new findings on the potential protective effect of manipulating Na+-K+-ATPase surface abundance during I-R injury by targeting one of these defined regions.

Regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase Cell Surface Abundance and Structural Determinants on the α1-Subunit

The concept that membrane trafficking is an important regulator of Na+-K+-ATPase is not a new one. In fact, early studies like those of Lamb and Ogden in HeLa cells pointed to CTS-induced changes in surface expression more than 30 years ago (28). Over the past two decades, this phenomenon has been observed in many other models, and a considerable amount of knowledge has been accumulated on the multiple physiological and pathological regulators of Na+-K+-ATPase surface abundance. Based on the results of our in vitro study in OK cells presented in Figs. 3 and 4, we propose that I-R be added to the growing list of those regulators. Studies that identified regulators also provided insights into the cellular pathways and compartments involved, but we are just beginning to understand the role of structural determinants on Na+-K+-ATPase enzyme complex in the integrated response to a given stimulus. As shown in Table 1, most of the determinants identified on the α1 polypeptide are located within the amino terminal part or the large cytoplasmic loop of the molecule. Additional determinants and mechanisms of regulation of surface abundance remain to be identified, and studies like those by Kimura et al. on the regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase trafficking by arrestins and spinophilin (25) point to additional roles for the large intracellular loop in particular.

I-R-Induced Decrease of Na+-K+-ATPase Cell Surface Abundance

The results from this study are consistent with an I-R-induced internalization of Na+-K+-ATPase units in OK cells. As shown in Fig. 3, the extent of I-R-induced internalization is comparable in α1- and α1-L499V-expressing cells, suggesting that the particular dileucine motif that we chose to mutate to increase surface expression is not involved in I-R-induced internalization itself, at least in this model. Although beyond the scope of this study, an investigation of the role of intracellular mediators such as ROS and PKCs, as well as the clathrin-coated pits network and the ubiquitin system in I-R-induced internalization of Na+-K+-ATPases may reveal a great deal about the underlying mechanism. Indeed, several of these machineries and mediators have been shown to regulate hypoxia-induced Na+-K+-ATPase internalization as part of a “phosphorylation-ubiquitination-recognition-endocytosis-degradation” (PURED) pathway (14, 15, 29) and are also important components of the cellular response during exposure to I-R, especially in the heart (11, 16, 33, 39). In addition, studies in cells expressing Na+-K+-ATPase α1 mutated on Ser-18 or one of the surrounding Lys (involved in hypoxia-induced internalization as shown in Table 1) may prove useful in future attempts to characterize the mechanism of I-R-induced internalization. Structural determinants may hence be instrumental to future studies on the mechanism underlying I-R-induced Na+-K+-ATPase internalization and its importance in I-R-induced cell death.

Mechanism of Protection Against I-R-Induced Injury

According to the data presented in Figs. 1 and 2, an increased number of Na+-K+-ATPase units at the cell surface correlates with an increased tolerance to I-R in α1-L499V-expressing cells. However, these studies do not reveal the underlying mechanism of protection. Additional Na+-K+-ATPase ion-pumping capacity at the cell surface may help preserve intracellular ion homeostasis during I-R, but studies like our initial characterization of the α1-L499V mutant itself (44) or the graded knockdown of α1 subunit (31) have shown that surface expression does not necessarily correlate with increased ion-pumping function. In fact, other non-ion-pumping functions of Na+-K+-ATPase may be involved, such as survival signaling or preservation of the integrity of intracellular structures (7, 8, 45). Clearly, further investigation in cells exposed to I-R is needed to clarify the relative contribution of Na+-K+-ATPase ion-pumping and non-ion-pumping functions in the protection afforded by increased cell surface expression.

In conclusion, a substantial number of studies have underscored the importance of surface abundance modulation in the regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase function. In addition, a number of structural determinants have been identified on the α-polypeptide, with variable degree of divergence among various α-isoforms and between different species. The exact role of these variations in tissue- and species-specific response to various stimuli and diseases remains to be established. The data presented here suggest that modulation of Na+-K+-ATPase cell surface abundance by targeting structural determinants on the α-subunit has a significant impact on I-R-induced cell injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart Lung Blood Institute Grant HL-36573. Y. Sottejeau is a Conventions Industrielles de Formation par la REcherche (CIFRE) fellow of the French National Agency for Technological Research (ANRT).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NASE antibody and plasmids used in this study are a gift from Dr. Pressley (Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX). We thank Drs. T. A. Pressley and Z. J. Xie (University of Toledo College of Medicine, Toledo, OH) for helpful discussion and input on the content of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aperia A. New roles for an old enzyme: Na,K-ATPase emerges as an interesting drug target. J Intern Med 261: 44–52, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev 61: 9–38, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benziane B, Chibalin AV. Frontiers: skeletal muscle sodium pump regulation: a translocation paradigm. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E553–E558, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bertorello AM, Sznajder JI. The dopamine paradox in lung and kidney epithelia: sharing the same target but operating different signaling networks. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 33: 432–437, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blanco G. Na,K-ATPase subunit heterogeneity as a mechanism for tissue-specific ion regulation. Semin Nephrol 25: 292–303, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blanco G, Mercer RW. Isozymes of the Na-K-ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F633–F650, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai T, Wang H, Chen Y, Liu L, Gunning WT, Quintas LE, Xie ZJ. Regulation of caveolin-1 membrane trafficking by the Na/K-ATPase. J Cell Biol 182: 1153–1169, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Y, Cai T, Wang H, Li Z, Loreaux E, Lingrel JB, Xie Z. Regulation of intracellular cholesterol distribution by Na/K-ATPase. J Biol Chem 284: 14881–14890, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Z, Krmar RT, Dada L, Efendiev R, Leibiger IB, Pedemonte CH, Katz AI, Sznajder JI, Bertorello AM. Phosphorylation of adaptor protein-2 mu2 is essential for Na+,K+-ATPase endocytosis in response to either G protein-coupled receptor or reactive oxygen species. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 35: 127–132, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chibalin AV, Ogimoto G, Pedemonte CH, Pressley TA, Katz AI, Feraille E, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Dopamine-induced endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase is initiated by phosphorylation of Ser-18 in the rat alpha subunit and Is responsible for the decreased activity in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 274: 1920–1927, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Churchill EN, Mochly-Rosen D. The roles of PKCdelta and epsilon isoenzymes in the regulation of myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 1040–1042, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Comellas AP, Kelly AM, Trejo HE, Briva A, Lee J, Sznajder JI, Dada LA. Insulin regulates alveolar epithelial function by inducing Na+/K+-ATPase translocation to the plasma membrane in a process mediated by the action of Akt. J Cell Sci 123: 1343–1351, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cotta-Done S, Leibiger IB, Efendiev R, Katz AI, Leibiger B, Berggren PO, Pedemonte CH, Bertorello AM. Tyrosine 537 within the Na+,K+-ATPase alpha-subunit is essential for AP-2 binding and clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J Biol Chem 277: 17108–17111, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dada LA, Chandel NS, Ridge KM, Pedemonte C, Bertorello AM, Sznajder JI. Hypoxia-induced endocytosis of Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells is mediated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and PKC-zeta. J Clin Invest 111: 1057–1064, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dada LA, Welch LC, Zhou G, Ben-Saadon R, Ciechanover A, Sznajder JI. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination are necessary for Na,K-ATPase endocytosis during hypoxia. Cell Signal 19: 1893–1898, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Downey JM. Free radicals and their involvement during long-term myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Annu Rev Physiol 52: 487–504, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Efendiev R, Budu CE, Bertorello AM, Pedemonte CH. G-protein-coupled receptor-mediated traffic of Na,K-ATPase to the plasma membrane requires the binding of adaptor protein 1 to a Tyr-255-based sequence in the alpha-subunit. J Biol Chem 283: 17561–17567, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ewart HS, Klip A. Hormonal regulation of the Na+-K+-ATPase: mechanisms underlying rapid and sustained changes in pump activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C295–C311, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garty H, Karlish SJ. Role of FXYD proteins in ion transport. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 431–459, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geering K. Function of FXYD proteins, regulators of Na, K-ATPase. J Bioenerg Biomembr 37: 387–392, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Geering K. Functional roles of Na,K-ATPase subunits. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 526–532, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottardi CJ, Dunbar LA, Caplan MJ. Biotinylation and assessment of membrane polarity: caveats and methodological concerns. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 268: F285–F295, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaplan JH. Biochemistry of Na,K-ATPase. Annu Rev Biochem 71: 511–535, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khundmiri SJ, Bertorello AM, Delamere NA, Lederer ED. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase in response to parathyroid hormone requires ERK-dependent phosphorylation of Ser-11 within the alpha1-subunit. J Biol Chem 279: 17418–17427, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimura T, Allen PB, Nairn AC, Caplan MJ. Arrestins and spinophilin competitively regulate Na+,K+-ATPase trafficking through association with a large cytoplasmic loop of the Na+,K+-ATPase. Mol Biol Cell 18: 4508–4518, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirchhausen T. Adaptors for clathrin-mediated traffic. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 15: 705–732, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klisic J, Zhang J, Nief V, Reyes L, Moe OW, Ambuhl PM. Albumin regulates the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in OKP cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3008–3016, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lamb JF, Ogden P. Internalization of ouabain and replacement of sodium pumps in the plasma membranes of HeLa cells following block with cardiac glycosides. Q J Exp Physiol 67: 105–119, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lecuona E, Trejo HE, Sznajder JI. Regulation of Na,K-ATPase during acute lung injury. J Bioenerg Biomembr 39: 391–395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Z, Xie Z. The Na/K-ATPase/Src complex and cardiotonic steroid-activated protein kinase cascades. Pflügers Arch 457: 635–644, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liang M, Tian J, Liu L, Pierre S, Liu J, Shapiro J, Xie ZJ. Identification of a pool of non-pumping Na/K-ATPase. J Biol Chem 282: 10585–10593, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu J, Shapiro JI. Regulation of sodium pump endocytosis by cardiotonic steroids: molecular mechanisms and physiological implications. Pathophysiology 14: 171–181, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Misra MK, Sarwat M, Bhakuni P, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Oxidative stress and ischemic myocardial syndromes. Med Sci Monit 15: RA209–RA219, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murphy E, Eisner DA. Regulation of intracellular and mitochondrial sodium in health and disease. Circ Res 104: 292–303, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Ion transport and energetics during cell death and protection. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 115–123, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pierre SV, Xie Z. The Na,K-ATPase receptor complex: its organization and membership. Cell Biochem Biophys 46: 303–316, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pierre SV, Yang C, Yuan Z, Seminerio J, Mouas C, Garlid KD, Dos-Santos P, Xie Z. Ouabain triggers preconditioning through activation of the Na+,K+-ATPase signaling cascade in rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res 73: 488–496, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pitts KR, Toombs CF. Coverslip hypoxia: a novel method for studying cardiac myocyte hypoxia and ischemia in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1801–H1812, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Powell SR, Divald A. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in myocardial ischaemia and preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res 85: 303–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prassas I, Diamandis EP. Novel therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 926–935, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rieger AM, Hall BE, Luong le T, Schang LM, Barreda DR. Conventional apoptosis assays using propidium iodide generate a significant number of false positives that prevent accurate assessment of cell death. J Immunol Methods 358: 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C509–C536, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Skou JC. The influence of some cations on an adenosine triphosphatase from peripheral nerves. Biochim Biophys Acta 23: 394–401, 1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sottejeau Y, Belliard A, Duran MJ, Pressley TA, Pierre SV. Critical role of the isoform-specific region in alpha1-Na,K-ATPase trafficking and protein Kinase C-dependent regulation. Biochemistry 49: 3602–3610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tian J, Li X, Liang M, Liu L, Xie JX, Ye Q, Kometiani P, Tillekeratne M, Jin R, Xie Z. Changes in sodium pump expression dictate the effects of ouabain on cell growth. J Biol Chem 284: 14921–14929, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Welch LC, Lecuona E, Briva A, Trejo HE, Dada LA, Sznajder JI. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) participates in the hypercapnia-induced Na,K-ATPase downregulation. FEBS Lett. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xie Z, Cai T. Na+-K+–ATPase-mediated signal transduction: from protein interaction to cellular function. Mol Interv 3: 157–168, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xie Z, Xie J. The Na/K-ATPase-mediated signal transduction as a target for new drug development. Front Biosci 10: 3100–3109, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yudowski GA, Efendiev R, Pedemonte CH, Katz AI, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Phosphoinositide-3 kinase binds to a proline-rich motif in the Na+,K+-ATPase alpha subunit and regulates its trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6556–6561, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]