Abstract

Renal ammonia excretion is the predominant component of renal net acid excretion. The majority of ammonia excretion is produced in the kidney and then undergoes regulated transport in a number of renal epithelial segments. Recent findings have substantially altered our understanding of renal ammonia transport. In particular, the classic model of passive, diffusive NH3 movement coupled with NH4+ “trapping” is being replaced by a model in which specific proteins mediate regulated transport of NH3 and NH4+ across plasma membranes. In the proximal tubule, the apical Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE-3, is a major mechanism of preferential NH4+ secretion. In the thick ascending limb of Henle's loop, the apical Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter, NKCC2, is a major contributor to ammonia reabsorption and the basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE-4, appears to be important for basolateral NH4+ exit. The collecting duct is a major site for renal ammonia secretion, involving parallel H+ secretion and NH3 secretion. The Rhesus glycoproteins, Rh B Glycoprotein (Rhbg) and Rh C Glycoprotein (Rhcg), are recently recognized ammonia transporters in the distal tubule and collecting duct. Rhcg is present in both the apical and basolateral plasma membrane, is expressed in parallel with renal ammonia excretion, and mediates a critical role in renal ammonia excretion and collecting duct ammonia transport. Rhbg is expressed specifically in the basolateral plasma membrane, and its role in renal acid-base homeostasis is controversial. In the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD), basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase enables active basolateral NH4+ uptake. In addition to these proteins, several other proteins also contribute to renal NH3/NH4+ transport. The role and mechanisms of these proteins are discussed in depth in this review.

Keywords: acidosis, alkalosis, ammonia

ammonia1 metabolism and transport are critical components of biological processes in almost all organs. In the kidney, ammonia is a central component of the renal regulation of acid-base homeostasis. Under basal conditions, renal ammonia excretion comprises 50–70% of net acid excretion. During metabolic acidosis, increases in renal ammonia excretion comprise 80–90% of the increase in net acid excretion both in humans (89) and close to 100% of the increase in rodent models (61, 62). Decreased renal ammonia excretion independent of defects in urine acidification is present in the most common form of renal tubular acidosis in humans, type IV RTA (50).

Renal ammonia metabolism involves both intrarenal ammoniagenesis and epithelial cell-specific transport of either NH3 or NH4+. In this review, we discuss pertinent aspects of ammonia chemistry, renal ammoniagenesis, and renal epithelial segment ammonia transport, and then conclude with updated information regarding the specific proteins involved in renal epithelial cell NH3 and NH4+ transport.

Ammonia Chemistry

Ammonia exists in two molecular forms, NH3 and NH4+. The relative amounts of each are governed by the buffer reaction: NH3 + H+ ↔ NH4+. This reaction occurs essentially instantaneously and has a pKa′ under biologically relevant conditions of ∼9.15. Accordingly, at pH 7.4 ∼98.3% of total ammonia is present as NH4+ and only ∼1.7% is present as NH3. Because most biological fluids exist at a pH substantially below the pKa′ of this buffer reaction, small changes in pH cause exponential changes in NH3 concentration, but do not substantially change the NH4+ concentration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Influence of pH on NH3 and NH4+ concentration

| NH3 |

NH4+ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Concentration, μmol/l | % Change | Concentration, μmol/l | % Change |

| 5.00 | 0.071 | −99.6% | 999.9 | 1.8% |

| 6.00 | 0.71 | −96% | 999.3 | 1.7% |

| 6.50 | 2.22 | −87% | 997.8 | 1.6% |

| 7.00 | 7.03 | −60% | 993.0 | 1.1% |

| 7.20 | 11.1 | −36% | 988.9 | 0.6% |

| 7.40 | 17.5 | 0% | 982.5 | 0.0% |

| 7.60 | 27.4 | 57% | 972.6 | −1.0% |

Calculations were based upon solution with 1 mmol/l total ammonia and pKa′ for NH3 + H+↔NH4+ buffer reaction of 9.15. The % Change columns reflect change from pH 7.40.

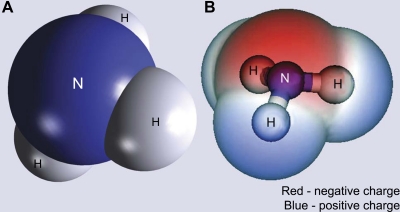

NH3, although uncharged, has an asymmetric arrangement of positively charged hydrogen nuclei surrounding a central nitrogen; this results in NH3 being a relatively polar molecule (Fig. 1). Quantitatively, NH3 has a molecular dipole moment, a measure of polarity, of 1.46 D. This compares with measurements of 1.85 for H2O, 1.08 for HCl, and 1.69 for ethanol, other small, uncharged, but polar, compounds. As a consequence of this molecular polarity, NH3 has both high water solubility and limited lipid permeability (11, 85). Indeed, several mammalian plasma membranes have been shown to have very low NH3 permeability, such as the stomach, colon, and thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) (52, 95, 99). Like other small, uncharged renal solutes, such as H2O and urea, recent evidence indicates that protein-mediated NH3 transport contributes to the rapid rates of NH3 transport observed in the kidney.

Fig. 1.

Model of NH3. A: space-filling model of the atomic structure of NH3 that demonstrates the asymmetric distribution of hydrogen nuclei (H) surrounding the central nitrogen (N). B: electrostatic charge distribution of NH3. A positive charge (blue) is concentrated near the hydrogen nuclei, and a negative charge (red) is concentrated adjacent to the nitrogen.

NH4+ also has limited permeability across lipid bilayers in the absence of specific transport proteins. However, in aqueous solutions NH4+ and K+ have nearly identical biophysical characteristics (Table 2), which enables NH4+ transport at the K+-transport site of essentially all K+ transporters, including many in the kidney (106). In addition, specific Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms can function in Na+/NH4+ exchange mode and contribute to renal epithelial ammonia transport.

Table 2.

| Cation | Ionic Radius, Å | Stokes Radius, Å | Mobility in H2O, 10−4 cm2•s−1•V−1 | Transference No. in H2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH4+ | 0.133 | 1.14 | 7.60 | 0.49 |

| K+ | 0.143 | 1.14 | 7.62 | 0.49 |

Renal Ammoniagenesis

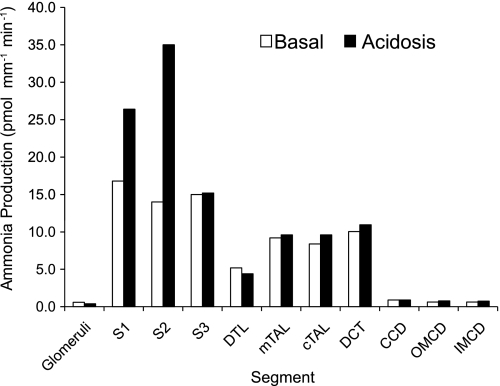

Ammonia, in contrast to most other urinary solutes, is produced in the kidney, and the sum of urinary ammonia and renal vein ammonia substantially exceeds renal arterial ammonia delivery. Thus renal ammoniagenesis is central to ammonia homeostasis. Multiple excellent reviews of ammoniagenesis have been published (24, 97), so this will not be discussed in detail here. Importantly, although almost all renal epithelial cells can produce ammonia, the proximal tubule is the primary site for physiologically relevant ammoniagenesis. Studies using microdissected renal structures have shown that the glomeruli, S1, S2, and S3 portions of the proximal tubule, the descending thin limb of the loop of Henle (DTL), medullary (mTAL) and cortical TAL, distal convoluted tubule (DCT), cortical collecting duct (CCD), outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), and inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) can synthesize ammonia, with glutamine being the primary metabolic substrate (25, 37). Ammoniagenesis increases in response to metabolic acidosis (Fig. 2), but predominantly in the S1 and S2 proximal tubule segments (37, 114). Metabolic acidosis may also increase ammoniagenesis in the S3 proximal tubule segment (80).

Fig. 2.

Ammonia production in various renal segments: basal and acidosis-stimulated rates. Ammonia production rates in different renal components were measured in microdissected epithelial cell segments from rats on control diets and after induction of metabolic acidosis. All segments tested produced ammonia. Metabolic acidosis increased total renal ammoniagenesis, but only through increased production in proximal tubule segments (S1, S2, and S3). Rates were calculated from measured ammonia production rates and mean length per segment as described (37). DTL, descending thin limb of Henle's loop; mTAL, medullary thick ascending limb of Henle's loop; cTAL, cortical thick ascending limb of Henle's lop; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; CCD, cortical collecting duct; OMCD, outer medullary collecting duct; IMCD, inner medullary collecting duct.

Ammonia Transport Summary

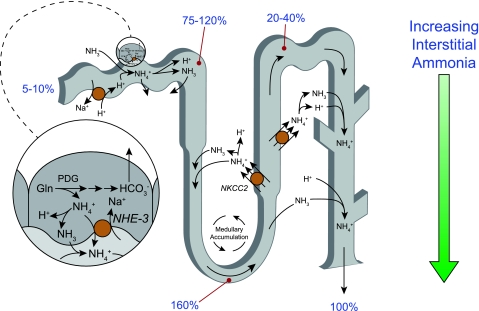

Ammonia produced in the proximal tubule is secreted preferentially into the luminal fluid, although there is some transport across the basolateral membrane. In distal proximal tubule segments, such as the S3 segment, there may also be ammonia reabsorption. The TAL reabsorbs the majority of luminal ammonia, resulting in total ammonia delivery to distal nephron segments being only ∼20–40% of total excreted ammonia. Some of the ammonia that the TAL reabsorbs undergoes recycling involving the DTL, which contributes to generation of an axial interstitial ammonia concentration gradient. Distal segments then secrete ammonia; the collecting duct is the site of the majority of ammonia secretion and involves parallel H+ and NH3 secretion. Figure 3 summarizes ammonia transport along the various renal epithelial cell segments. Below, we will discuss the currently available information regarding the specific ammonia transport mechanisms present in the apical and basolateral plasma membranes of renal epithelial cells in each of these segments.

Fig. 3.

Ammonia transport along the various renal epithelial segments. Ammonia is primarily produced in the proximal tubule. It is preferentially secreted into the luminal fluid through mechanisms which involve NHE-3-mediated Na+/NH4+ exchange, NH4+ transport through Ba2+-inhibitable K+ channels, and an uncharacterized NH3 transport pathway. Ammonia is reabsorbed by the TAL through a process primarily involving Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC2)-mediated NH4+ reabsorption. Recycling of ammonia through secretion in the DTL results in ammonia delivery to the turn of the loop of Henle that exceeds total excreted ammonia. NH4+ reabsorption in the TAL, however, results in total ammonia delivery to distal nephron segments that accounts for only a minority of total excreted ammonia. Ammonia secretion in the collecting duct involves parallel H+ and NH3 secretion. Numbers in blue reflect proportion of total urinary ammonia delivered to indicated sites. Specific details of ammonia secretion in each of these nephron segments are provided in the text.

Proximal Tubule

NHE-3.

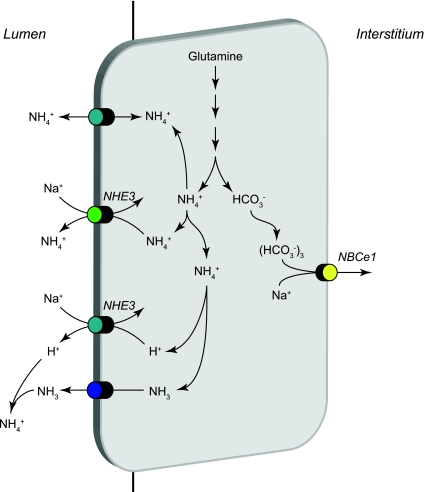

The apical Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-3 is likely to be a major mechanism of apical plasma membrane NH4+ secretion in the proximal tubule (Fig. 4). NHE-3 is a member of an extended family of Na+/H+ exchangers. NHE-3-mediated ammonia secretion likely involves substitution of NH4+ for H+ at the cytosolic H+ binding site, resulting in Na+/NH4+ exchange activity. Studies in proximal tubule brush-border membrane vesicles show that cytosolic NH4+ competes with cytosolic H+ for exchange with luminal Na+, enabling Na+/NH4+ exchange (4, 56). Although these studies showed that extracellular NH4+ can compete with luminal Na+ for reabsorption by NHE-3, the higher intracellular NH4+ concentration due to intracellular ammoniagenesis combined with lower intracellular Na+ concentration favors preferential Na+/NH4+ exchange, resulting in Na+ uptake and secretion of NH4+ secretion. Studies examining in vitro microperfused proximal tubule segments showed that combining a low luminal Na+ concentration with the Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor amiloride decreased ammonia secretion and that ammonia secretion was not due to luminal acidification (78). Similarly, studies examining in situ microperfused proximal tubule segments showed that the addition of the Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor EIPA to the nonselective K+ channel blocker Ba2+ decreased ammonia secretion by ∼50% compared with rates when only Ba2+ was present (94). Thus multiple lines of evidence support NHE-3 mediating an important role in proximal tubule NH4+ secretion.

Fig. 4.

Ammonia transport in the proximal tubule. Ammonia is produced in the proximal tubule primarily from metabolism of glutamine and occurs primarily in the mitochondria. The enzymatic details of ammoniagenesis are not shown. Three transport mechanisms appear to mediate preferential apical ammonia secretion. These include Na+/NH4+ exchange via NHE-3, parallel NH3 secretion and NHE-3-mediated Na+/H+ exchange, and a Ba2+-sensitive NH4+ conductance likely mediated by apical K+ channels. HCO3− is produced in equimolar amounts as NH4+ in the process of ammoniagenesis and is primarily transported across the basolateral plasma membrane by NBCe1. Minor components of basolateral NH4+ uptake via Na+-K+-ATPase and by basolateral K+ channels are not shown.

Changes in NHE-3 activity may alter renal ammonia metabolism in response to metabolic acidosis. Metabolic acidosis increases both NHE-3 expression (1) and, in studies examining in vitro microperfused S2 segments, proximal tubule ammonia secretion (81). The increase in both NHE-3 expression and ammonia secretion appears to require AT1 receptor activation (81). The list of pathways and physiological conditions that alter NHE-3 activity is extensive, but with the exception of metabolic acidosis they have not been correlated with changes in proximal tubule ammonia secretion.

Apical K+ channels.

K+ channels are a second mechanism of proximal tubule ammonia transport. Because of intracellular electronegativity, K+ channel-mediated NH4+ transport most likely results in net ammonia reabsorption under basal conditions. Increased luminal K+ concentration increased net ammonia secretion through mechanisms not involving Na+/H+ exchange activity (79), suggesting that luminal K+ may inhibit NH4+ reabsorption through a common transport mechanism, most likely apical K+ channels. Furthermore, luminal Ba2+, a nonspecific K+ channel inhibitor, inhibited proximal tubule ammonia secretion when combined with EIPA, whereas EIPA alone did not (94). Multiple K+ channels are present in the apical membrane of the proximal tubule, including KCNA10, TWIK-1, and KCNQ1/KCNE1; which of these mediate ammonia transport is not currently known.

Uncharacterized apical NH3 transport.

In addition to Na+/NH4+ exchange mediated by NHE-3 and NH4+ transport mediated by Ba2+-sensitive K+ channels, there may also be NH3 transport across the apical plasma membrane. Studies examining in situ microperfused PCT segments showed that ∼50% of ammonia secretion persisted even after inhibition of NHE-3 and Ba2+-sensitive K+ channels (94). In other studies, luminal acidification stimulated ammonia secretion despite the presence of high concentrations of EIPA, which were sufficient to inhibit NHE-3-mediated bicarbonate reabsorption, suggesting a significant role for NHE-3-independent NH3 secretion (93). This apparent NH3 permeability could either reflect passive, lipid-phase NH3 diffusion or transport by a currently unidentified apical NH3 transport process.

Basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase.

Basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase can enable cellular uptake of interstitial ammonia, most likely through a mechanism involving substitution of NH4+ for K+ at the K+ binding site. Mathematical modeling suggests that basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated NH4+ uptake may mediate as much as 20–30% of net ammonia secretion, but these assumptions are highly dependent on interstitial ammonia concentration (109).

Basolateral K+ channels.

Basolateral K+ channel-mediated NH4+ transport is also likely, but probably has a very limited role in proximal tubule ammonia transport (109). Because of intracellular electronegativity, K+ channel-mediated NH4+ transport is likely to facilitate cellular NH4+ uptake. The specific basolateral K+ channels that mediate this process have not been determined.

TAL

Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport.

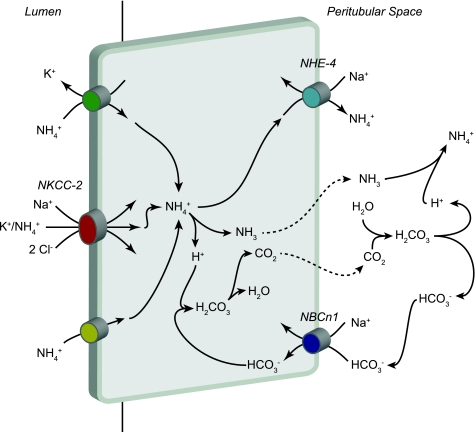

The TAL is an important site for luminal bicarbonate reabsorption (Fig. 5). The Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC2) is the major mechanism for ammonia reabsorption in the TAL (36). Luminal NH4+ competes with K+ for binding to the K+-transport site, enabling alterations in luminal K+ in hypokalemia and hyperkalemia to alter net NH4+ transport (32, 33). The ability of NH4+ to be transported at the K+ binding site of NKCC2 may also contribute to TAL NaCl transport (110). NH4+-coupled Na+ uptake by NKCC2 may be particularly important in Bartter's syndrome, type II, where defects in the ROMK channel inhibit K+ recycling and thereby preclude normal rates of K+-coupled Na+ uptake (110). Metabolic acidosis increases TAL ammonia reabsorption (35); this appears to involve increased NKCC2 protein and mRNA expression (8) and to depend on the glucocorticoid increase that occurs with chronic metabolic acidosis (9).

Fig. 5.

Ammonia reabsorption in the TAL. The primary mechanism of ammonia reabsorption in the TAL is via substitution of NH4+ for K+ and transport by NKCC2. Electroneutral K+/NH4+ exchange and conductive K+ transport are also present, but are quantitatively less significant components of apical K+ transport. Diffusive NH3 transport across the apical plasma membrane is present, but is not quantitatively significant. Cytosolic NH4+ can exit via basolateral NHE-4. A second mechanism of basolateral NH4+ exit may involve dissociation to NH3 and H+, with NH3 exit via an uncharacterized, presumably diffusive, mechanism and buffering of intracellular H+ released via sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter NBCn1-mediated HCO3− entry.

K+ channels.

In the TAL, K+ channels can contribute to luminal NH4+ uptake when apical NKCC2 cotransport is inhibited (6). However, NKCC2 inhibitors completely inhibit TAL ammonia transport, suggesting that apical K+ channels are unlikely to mediate a quantitatively important role in TAL ammonia transport (36).

K+/NH4+ exchange activity.

An electroneutral, Ba2+- and verapamil-inhibitable apical K+/NH4+ (H+) activity has been shown to be present in the apical membrane of the TAL (7). The gene product and the protein that correlate with this transport activity have not yet been identified. However, the observation that NKCC2 inhibitors nearly completely inhibit the transcellular component of TAL ammonia transport suggests that K+/NH4+ (H+) exchange activity may not have a major role in TAL ammonia reabsorption.

Apical NHE-3.

Apical NHE-3 is also present in the TAL (2). However, since this transporter likely secretes NH4+, and the TAL reabsorbs NH4+, NHE-3 appears unlikely to mediate an important role in loop of Henle ammonia transport.

Basolateral NHE-4.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that basolateral ammonia exit in the TAL likely involves Na+/NH4+ exchange mediated by NHE-4. Purified mTAL basolateral membrane vesicles exhibit Na+/H+ exchange activity, which can also function in a Na+/NH4+ exchange mode (15). Two Na+/H+ exchange isoforms are expressed in the mTAL basolateral plasma membrane, NHE-1 and NHE-4 (20). Recent studies have shown a critical role for NHE-4 in mTAL ammonia absorption, presumably by mediating basolateral Na+/NH4+ exchange. Metabolic acidosis increased mTAL NHE-4 mRNA expression and transport activity (16), and NHE-4 gene deletion inhibited mTAL ammonia absorption, decreased generation of the medullary interstitial ammonia concentration gradient, and decreased renal ammonia excretion in response to metabolic acidosis (16). Inhibiting NHE-1 with low concentrations of peritubular EIPA did not alter ammonia reabsorption, suggesting that NHE-1 does not contribute significantly to TAL ammonia reabsorption. Higher concentrations of peritubular EIPA, sufficient to inhibit NHE-4, decreased ammonia reabsorption by ∼30%, consistent with a role of basolateral NHE-4 in TAL ammonia reabsorption. NHE-4 deletion did not alter basal ammonia excretion, but did decrease basal urine pH, which may have enabled normal rates of ammonia excretion in the absence of NHE-4 (16). Thus NHE-4 appears to mediate an important role in the mTAL basolateral ammonia exit, which is necessary for normal response to metabolic acidosis.

NBCn1.

A second mechanism of basolateral ammonia transport in the TAL may involve dissociation of cytosolic NH4+ to NH3 and H+, with basolateral NH3 exit and buffering of the intracellular H+ load by bicarbonate. In this model, the method of basolateral NH3 exit has not been experimentally defined. Basolateral bicarbonate uptake appears to buffer the associated H+ load, and current data suggest that the electroneutral, sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter NBCn1 is critical to this process. In animals, metabolic acidosis increased mTAL ammonia reabsorption (34) and increased mTAL NBCn1 expression and activity (60, 86). Since the electrochemical gradient for bicarbonate transport by NBCn1 favors cellular bicarbonate uptake, not exit, increased NBCn1 expression likely does not contribute to the increased bicarbonate reabsorption seen with metabolic acidosis. Instead, increased bicarbonate uptake enables a “bicarbonate shuttle” mechanism which enables parallel H+ and NH3 transport (Fig. 5). Further support for this model comes from in vitro studies. In the mTAL cell line, ST-1, inhibition of NBCn1 blunted uptake of the ammonia analog [14C]methylammonia (14C-MA) (63). Finally, NBCn1 expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes increased 14C-MA uptake (63). Thus multiple lines of evidence suggest NBCn1 facilitates basolateral TAL ammonia transport through a “bicarbonate-shuttle” mechanism.

TDL

Some of the ammonia absorbed by the mTAL undergoes recycling into the DTL, resulting in countercurrent amplification of medullary interstitial ammonia concentration. Ammonia recycling predominantly involves NH3 transport, with a smaller component of NH4+ transport (30). The molecular mechanisms of DTL NH3, and NH4+ transport have not been determined.

Summary of Loop of Henle Ammonia Transport

Ammonia absorption by the TAL and ammonia secretion into the DTL produces two important elements of renal ammonia transport. The first is development of an axial ammonia concentration gradient in the medullary interstitium that parallels the hypertonicity gradient. Second, ammonia absorption by the mTAL exceeds recycling in the DTL and thereby results in net ammonia reabsorption in the loop of Henle. Thus, even though total delivered luminal ammonia at the end of the micropuncturable proximal tubule is similar to net urinary ammonia excretion, ammonia reabsorption in the loop of Henle reduces ammonia delivery to the distal tubule to only 20–40% of final urinary ammonia content (26, 40). Ammonia secretion in more distal segments is necessary for normal renal ammonia excretion.

Distal Tubule Ammonia Transport

Ammonia transport in the regions of the distal tubule before the collecting duct, i.e., the DCT, CNT, and initial collecting tubule (ICT), is difficult to quantify due to the difficulty in obtaining micropuncture or isolated, perfused tubule data on deep cortical nephrons or portions distal to points where nephrons merge in these segments. Net ammonia secretion occurs between the early and late portions of the distal tubule accessible to micropuncture and accounts for ∼10–15% of total urinary ammonia excretion under basal conditions (92, 113). This figure likely represents an underestimate of the contribution of the CNT and ICT, because a significant portion of these segments is distal to branch points.

Collecting Duct Ammonia Transport

It has been recognized for years that ammonia secretion by the collecting duct accounts for the majority of urinary ammonia content. Several studies have examined the CCD, OMCD, and IMCD and have uniformly shown that collecting duct ammonia secretion involves parallel NH3 and H+ transport, with little-to-no pH-independent NH4+ permeability (26, 57). H+ secretion likely involves both H+-ATPase and H+-K+-ATPase. These proteins have been the subject of several excellent recent reviews (14, 18, 23, 39) and are not reviewed here. Intact carbonic anhydrase activity, most likely mediated by carbonic anhydrase II (CA II), is necessary for collecting duct ammonia secretion, probably by supplying cytosolic H+ for secretion (101). Although collecting duct NH3 transport was initially thought to involve diffusive NH3 movement across plasma membranes, recent studies have shown that a variety of specific proteins are essential for collecting duct ammonia secretion.

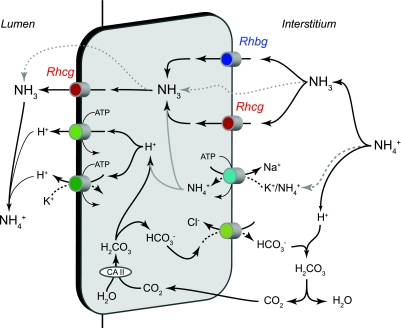

Several transporters present in the collecting duct have been examined for their potential role in collecting duct ammonia secretion, including the NKCC2, NKCC1, Na+-K+-ATPase, H+-K+-ATPase, aquaporins, and the Rh glycoproteins, Rhcg and Rhbg. Of these, the only transporters that clearly have important roles in collecting duct ammonia secretion are Na+-K+-ATPase in the IMCD, and most recently the Rh glycoproteins, Rhbg and Rhcg. Figure 6 shows our current model of collecting duct ammonia secretion.

Fig. 6.

Model of collecting duct ammonia secretion. In the interstitium, NH4+ is in equilibrium with NH3 and H+. NH3 is transported across the basolateral membrane through both Rhesus glycoproteins Rhbg and Rhcg. In the IMCD, basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase is a major mechanism of basolateral NH4+ uptake, followed by dissociation of NH4+ to NH3 and H+ (grey lines). Intracellular NH3 is secreted across the apical membrane by apical Rhcg. H+ secreted by H+-ATPase and H+-K+-ATPase combine with luminal NH3 to form NH4+, which is “trapped” in the lumen. In addition, there may also be minor components of diffusive NH3 movement across both the basolateral and apical plasma membranes (dotted lines). The intracellular H+ that is secreted by H+-ATPase and H+-K+-ATPase is generated by carbonic anhydrase (CA) II-accelerated CO2 hydration that forms carbonic acid, which dissociates to H+ and HCO3−. Basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchange transports HCO3− across the basolateral membrane; HCO3− combines with H+ released from NH4+, to form carbonic acid, which dissociates to CO2 and water. This CO2 can recycle into the cell, supplying the CO2 used for cytosolic H+ production. The net result is NH4+ transport from the peritubular space into the luminal fluid. In the non-A, non-B cell, which lacks substantial basolateral Rhcg expression, Rhbg is likely the primary basolateral NH3 transport mechanism. The B-type intercalated cell, which lacks detectable Rhbg and Rhcg expression, likely mediates transcellular ammonia secretion through mechanisms only involving lipid-phase NH3 diffusion and thus transports ammonia at significantly slower rates.

Na+-K+-ATPase.

Na+-K+-ATPase is present in the basolateral plasma membrane of renal epithelial cells, and its expression is greatest in the mTAL, with lesser expression in the cortical thick ascending limb, DCT, CCD, MCD, and the proximal tubule (48). NH4+ competes with K+ at the K+-binding site of Na+-K+-ATPase, enabling Na+-NH4+ exchange (59, 103). However, the relative affinities of Na+-K+-ATPase for NH4+, ∼11 mM, and K+, ∼1.9 mM, have important effects on Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated NH4+ transport. In the cortex, interstitial ammonia concentrations are ∼1 mM, suggesting NH4+ is unlikely to be transported to a significant extent by basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase (59). Moreover, even in the presence of high concentrations of peritubular ammonia, basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase does not appear to contribute to CCD ammonia secretion (58). In contrast, interstitial ammonia concentrations in the inner medulla are high, and Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated basolateral NH4+ uptake is critical for IMCD ammonia and acid secretion (59, 103). In hypokalemia, studies examining the IMCD show that decreased interstitial K+ concentration enables increased NH4+ uptake by Na+-K+-ATPase and increased rates of NH4+ secretion which do not involve changes in Na+-K+-ATPase expression (102). In the outer medulla, particularly in the outer stripe, interstitial ammonia concentrations are sufficiently high to postulate a role for Na+-K+-ATPase in ammonia secretion, but this prediction has not been experimentally tested.

Rh glycoproteins.

In the last decade, several laboratories have contributed to the discovery of Rh glycoproteins in the kidney and the demonstration of their important contribution to renal ammonia transport. Rh glycoproteins are mammalian orthologs of Mep/AMT proteins, ammonia transporter family proteins present in yeast, plants, bacteria, and many other organisms. Three mammalian Rh glycoproteins have been identified to date, Rh A glycoprotein (RhAG/Rhag), Rh B glycoprotein (RhBG/Rhbg), and Rh C glycoprotein (RhCG/Rhcg). By convention, Rh A glycoprotein is termed RhAG in human tissues and is termed Rhag in nonhumans; a similar terminology is used for RhBG/Rhbg and RhCG/Rhcg.

RhAG/Rhag.

Rh A glycoprotein (RhAG/Rhag) is a component of the Rh complex in erythrocytes, which consists of the nonglycosylated Rh proteins, RhD and RhCE in humans and Rh30 in nonhuman mammals, in association with RhAG/Rhag. RhAG mediates electroneutral NH3 transport (74, 88, 111, 112). However, RhAG/Rhag is an erythrocyte and erythroid-precursor specific protein (66), and studies in the human kidney found no evidence of renal RhAG expression (105). At present, RhAG/Rhag is thought unlikely to contribute to renal ammonia transport.

RhBG/Rhbg.

RhBG/Rhbg is expressed in a wide variety of organs involved in ammonia metabolism, including kidneys, liver, skin, lung, stomach, and gastrointestinal tract (42, 44, 68, 87, 98, 107). In kidneys, the DCT, CNT, ICT, CCD, OMCD, and the IMCD express basolateral Rhbg (87, 98). In general, both intercalated and principal cells express Rhbg, and intercalated cell Rhbg expression exceeds principal cell expression. The exceptions are the CCD B-type intercalated cell, which does not express Rhbg detectable with immunohistochemistry, and the IMCD, where only intercalated cells express Rhbg (98). Rhbg's basolateral expression appears due to basolateral stabilization through specific interactions of its cytoplasmic carboxy-terminus with ankyrin-G (69). The human kidney expresses high amounts of RhBG mRNA (68), but a recent study using a variety of antibodies did not detect RhBG protein expression (17).

RhBG/Rhbg transports both ammonia and the ammonia analog methylammonia. Most studies show that Rhbg mediates electroneutral, Na+- and K+-independent, NH3 transport (71, 73, 119), while another identified electrogenic NH4+ transport (84). The explanation for this discrepancy is not known. In all of these studies, the affinity for ammonia was ∼2–4 mM. Importantly, both electroneutral NH3 transport and electrogenic NH4+ transport facilitate basolateral ammonia uptake.

Rhbg's specific role in renal ammonia metabolism is controversial at present. Several studies suggest it can contribute to ammonia secretion in specific conditions. In the mouse, metabolic acidosis increased renal ammonia excretion and induced a progressive, time-dependent increase in Rhbg protein in the CNT, ICT, CCD, OMCD, and the IMCD in one study (12). In another study, which examined only the OMCD, metabolic acidosis increased Rhbg mRNA expression (protein expression was not examined) (22). These studies contrast with findings in the rat, where metabolic acidosis did not detectably alter Rhbg expression (90). In mice, genetic deletion of pendrin, an apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger present in type B and non-A, non-B intercalated cells, decreased Rhbg expression (55). Since pendrin deletion increased urine acidification, which otherwise would increase ammonia excretion, decreased Rhbg expression may have normalized ammonia excretion rates. Finally, Rhcg deletion, either from the entire collecting duct or only from intercalated cells, increased Rhbg expression in acid-loaded mice, suggesting increased Rhbg protein expression contributed to ammonia excretion in the absence of Rhcg (61, 62). The consistent observation in the mouse that changes in Rhbg expression either parallel changes in ammonia excretion or compensate for genetic deletion of other proteins involved in renal acid-base homeostasis suggest Rhbg contributes to renal ammonia excretion.

However, studies examining genetic Rhbg deletion have reached differing conclusions as to Rhbg's physiological role. In one study, mice with global Rhbg deletion were examined. These mice had normal basal acid-base parameters and basal ammonia excretion, normal increases in urinary ammonia excretion in response to acid loading, and normal basolateral NH3 and NH4+ permeability in microperfused CCD segments (19). These findings suggested Rhbg did not contribute to renal ammonia metabolism. Our laboratory examined mice with intercalated cell-specific Rhbg deletion (12). Basal ammonia excretion was not altered, but there was a substantial adaptive change in proximal tubule glutamine synthetase expression, which may have enabled normal rates of unstimulated ammonia excretion. With acid loading, intercalated cell-specific Rhbg deletion significantly impaired the expected increase in urinary ammonia excretion. These findings suggested Rhbg expression contributes to renal ammonia excretion and that adaptive responses to Rhbg deletion may mask Rhbg's role under specific circumstances.

RhCG/Rhcg.

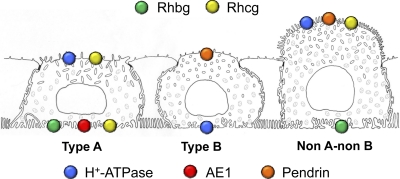

There is now substantial evidence that Rh C glycoprotein (RhCG/Rhcg) is critical for renal ammonia excretion. RhCG/Rhcg is widely expressed, including in kidneys, the central nervous system, testes, lung, liver, and throughout the gastrointestinal tract (42, 44, 67, 107). In the kidney, Rhcg is expressed in the same epithelial cell distribution as Rhbg, in the DCT, CNT, ICT, CCD, OMCD, and IMCD (27, 98). With the exception of the IMCD, in which only intercalated cells express Rhcg, both intercalated cells and nonintercalated cells (i.e., DCT cells, CNT cells, and principal cells) express Rhcg, and intercalated cell expression exceeds principal cell expression (27, 98). Detectable Rhcg expression is not observed in the B-type intercalated cell (43). The presence of Rhbg and Rhcg in both intercalated cells and principal cells is consistent with functional measurements of NH3 permeability in intercalated cells and principal cells (117). Figure 7 summarizes the expression of Rhbg and Rhcg in the different intercalated cell types.

Fig. 7.

Expression of Rhbg and Rhcg in different intercalated cell populations. The expression and localization of Rhbg and Rhcg differ in the type A, type B, and non-A, non-B intercalated cells. The type A intercalated cell, characterized by apical H+-ATPase and basolateral AE1, expresses apical and basolateral Rhcg and basolateral Rhbg. The type B intercalated cell, characterized by apical pendrin and basolateral H+-ATPase, does not express either Rhbg or Rhcg detectable by immunohistochemistry. The non-A, non-B intercalated cell, characterized by apical pendrin and apical H+-ATPase, expresses apical, but not basolateral, Rhcg and expresses basolateral Rhbg. This figure is based on a drawing originally prepared by Dr. Ki-Hwan Han.

Rhcg has a complex subcellular localization. Studies in the human, rat, and mouse kidney demonstrate that Rhcg-expressing cells exhibit both apical and basolateral Rhcg immunoreactivity, with the exception of the non-A, non-B intercalated cell, which has only apical Rhcg (17, 41, 53, 90, 91). Immunogold electron microscopy in both the rat and mouse kidney demonstrated that apical Rhcg is present in both the apical plasma membrane and subapical vesicles and that basolateral Rhcg is present in the basolateral plasma membrane (53, 91). Basolateral expression can be substantial; in the rat OMCD in the inner stripe, basolateral Rhcg is ∼25% of total cellular expression in intercalated cells and ∼40% in principal cells (91). Although initial studies in both the rat and mouse kidney did not identify basolateral Rhcg expression, more recent studies using improved immunohistochemistry techniques and a panel of anti-Rhcg antibodies confirmed basolateral Rhcg expression and demonstrated substantial quantitative differences in the amount of basolateral Rhcg immunolabel in different mouse strains (53).

Several studies have addressed the molecular ammonia species transported by RhCG/Rhcg. Some studies using heterologous expression in the X. laevis oocyte suggest that RhCG/Rhcg mediates electroneutral NH3 transport (71, 73, 119), while others have reported both NH3 and NH4+ transport (10). Measurement of apical plasma membrane NH3 and NH4+ permeability in the collecting duct of mice with global Rhcg deletion found decreased NH3 permeability, without a change in NH4+ permeability (13). Other studies reconstituted purified human RhCG into liposomes and demonstrated increased NH3 permeability but no change in NH4+ permeability (38, 75). Thus the majority of evidence suggests Rhcg/RhCG functions as a facilitated NH3 transporter.

Substantial evidence supports the conclusion that Rhcg mediates a critical role in renal ammonia excretion. In a variety of experimental models, Rhcg expression paralleled ammonia excretion. Metabolic acidosis significantly increased total Rhcg protein expression in both the OMCD and the IMCD, but not in the cortex (90). Rhcg mRNA expression was not altered significantly; therefore, posttranscriptional mechanisms may regulate Rhcg protein expression (90). In response to reduced renal mass, where there is increased single-nephron ammonia secretion, apical Rhcg expression increased in the CCD A-type intercalated cell and both apical and basolateral expression increased in the OMCD intercalated cell and in principal cells in the CCD and OMCD (54). Cyclosporine A nephropathy is associated with decreased Rhcg expression, which likely contributes to impaired ammonia excretion and development of metabolic acidosis in this model (65).

At least two distinct mechanisms contributed to increased apical plasma membrane Rhcg expression in response to metabolic acidosis. First, there was increased total cellular Rhcg protein expression (91). Second, there were changes in Rhcg's subcellular location. Under basal conditions, apical Rhcg was located both in the apical plasma membrane and in subapical sites in both principal and intercalated cells. In response to chronic metabolic acidosis, particularly in the intercalated cell, apical plasma membrane expression increased and subapical expression decreased (91). The relative importance of these two mechanisms differed in principal and intercalated cells, with subcellular distribution changes being the predominant adaptive response in the OMCD intercalated cell and increased protein expression being the predominant mechanism in the OMCD principal cell (91).

Changes in basolateral Rhcg expression have also been examined in a variety of models. Chronic metabolic acidosis increased basolateral plasma membrane Rhcg expression significantly in both intercalated cells and principal cells (54, 91). In contrast to apical plasma membrane Rhcg expression, the proportion of total cellular Rhcg that was present in the basolateral plasma membrane did not change, suggesting that redistribution from cytoplasmic sites to the basolateral plasma membrane was not a major regulatory mechanism (91). Basolateral Rhcg expression has also been studied in a model of reduced renal mass (54). In this model of the early response to renal ablation-infarction, in which there is increased single-nephron ammonia excretion, basolateral Rhcg expression increased in the CCD principal cell, OMCD intercalated cell, and the OMCD principal cell (54). At present, neither genetic nor pharmacological approaches are available to assess the functional significance of these changes in basolateral Rhcg expression. However, C57BL/6 mice have substantially greater basolateral Rhcg expression than Balb/C mice (53), and this correlates with a greater ability to increase renal ammonia excretion in response to an acid load (108).

Genetic deletion studies have confirmed Rhcg's key role in renal ammonia excretion. Global Rhcg deletion decreased basal ammonia excretion and impaired urinary ammonia excretion in response to metabolic acidosis (13). Collecting duct-specific Rhcg deletion produced similar findings, indicating that reduced ammonia excretion reflected impaired collecting duct ammonia secretion and was not an indirect effect of an extrarenal Rhcg-mediated mechanism (61). Global Rhcg deletion decreased both transepithelial ammonia permeability and apical membrane NH3 permeability in perfused collecting duct segments obtained from acid-loaded mice (13).

The observation that both intercalated and principal cells express Rhcg and that metabolic acidosis increased Rhcg in both cell types suggests that both cells contribute to transepithelial ammonia secretion. To test this prediction, recent studies examined mice with intercalated cell-specific Rhcg deletion (62). These studies showed that intercalated cell-specific Rhcg deletion did not alter the basal rate of ammonia excretion (62), suggesting principal cell Rhcg expression was sufficient for normal basal ammonia excretion. After acid loading, mice with intercalated cell-specific Rhcg deletion had an intact ability to increase urinary ammonia excretion during the first 2 days of metabolic acidosis. Because this was associated with a significantly lower urine pH, increased luminal H+ concentration, by shifting the NH3 + H+ ↔ NH4+ reaction to the right, may have decreased luminal NH3 concentration, thereby facilitating principal cell Rhcg-dependent NH3 secretion. Alternatively, the more acidic urine may result from the decreased NH3 permeability, which decreased NH3 entry and subsequent titration of secreted H+. Importantly, the finding of intact ammonia excretion in the early response to metabolic acidosis in mice with intercalated cell-specific Rhcg deletion contrasted with findings in mice with either global or collecting duct-specific Rhcg deletion, in which ammonia excretion was inhibited significantly (13, 61). Principal cell Rhcg expression appears to enable both normal basal ammonia excretion and to contribute to the increased ammonia excretion with metabolic acidosis, suggesting that the principal cell, in addition to the intercalated cell, can contribute to transepithelial ammonia secretion and thereby contribute to acid-base homeostasis.

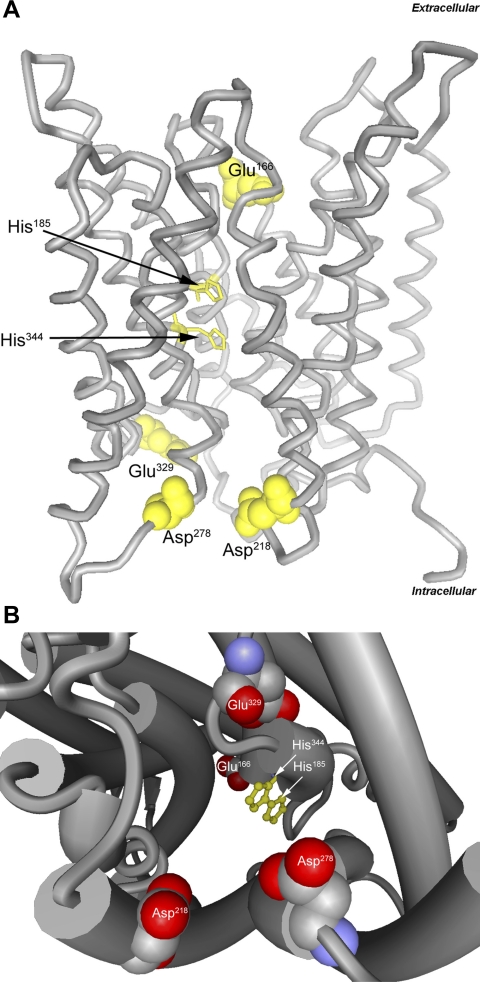

Tertiary structure of mammalian Rh glycoproteins.

Important studies examining the tertiary structure of Rh glycoproteins and related orthologs, Amt proteins, have led to substantial understanding of the molecular mechanism through which they transport ammonia. These studies used X-ray crystallographic approaches; initial studies examined Amt proteins, bacterial orthologs of Rh glycoproteins, and more recent studies examined first bacterial Rh glycoproteins and then human RhCG.

Bacterial Amt proteins are expressed in a homotrimeric state; each of the subunits has 11 transmembrane segments, with segments M1–M5 and M6–M10 exhibiting a quasi-twofold axis. The trimer has a net negative charge of −13.5 at the extracellular site and a net positive charge of +9 at the cytoplasmic site (51). An extracellular vestibule concentrates NH4+; in Escherichia coli AmtB, three highly conserved acidic residues, Phe107, Trp148, and Ser219, create a NH4+-binding site (3, 46, 118). This NH4+-binding site, and the differences in net charge at the extracellular and intracellular site, facilitate NH4+ interaction with the extracellular vestibule and likely explain the membrane voltage-dependent changes in affinity for the ammonia analog methylammonia (70). A 20-Å-long, narrow, hydrophobic central channel enables NH3, but not NH4+, movement, thereby providing molecular selectivity. NH3 movement through this channel is stabilized by a unique twin in-line histidine motif. In E. coli AmtB, stacked phenyl rings of two highly conserved phenylalanine residues, Phe107 and Phe215, appear to regulate entry of NH3 from the extracellular vestibule into the central channel.

More recent studies examined the tertiary structure of Rh glycoproteins using similar techniques. Nitrosomonas europaea is an obligate chemolithoautotrophic bacterium that can oxidize ammonia as its sole energy source; it is one of only four bacteria known to express Rh glycoproteins (47), and its Rh glycoprotein, NeRh50, is known to transport ammonia (21, 104). Two reports published simultaneously detailed the crystal structure of NeRh50 (64, 72). Multiple similarities between NeRh50 and Amt proteins were identified, including the homotrimeric structure with 11 transmembrane-spanning segments of each monomer, the central pore with the twin in-line histidine motif, and a phenylalanine residue that may regulate entry into the channel. An important difference between NeRh50 and Amt proteins was the lack of critical acidic residues in the extracellular vestibule present in Amt orthologs; this absence likely accounts for the differences in ammonia affinity between Rh glycoproteins, typically 1–4 mM, and the affinity of Amt proteins, typically in the low micromolar range (64, 72).

Most recently, the structure of human RhCG was determined (38). Again, a homotrimeric structure was demonstrated. Each monomer exhibited 12 transmembrane-spanning segments; the 12th segment, termed M0, was an additional amino-terminal helix. Helices M1–M5 and M6–M10 exhibited an in-plane quasi-twofold symmetry with respect to the plasma membrane. There were multiple conserved features, including acidic residues lining the extracellular vestibules, an external aperture gated by a phenylalanine residue, a largely hydrophobic channel lumen, and the twin in-line histidine motif in the center of the channel (38). The extracellular vestibule tryptophan, which in AmtB serves to recruit NH4+, was absent in both RhCG and NeRh50, but alternative acidic residues, Glu166 in the extracellular vestibule and Asp218, Asp278, and Glu329 in the intracellular vestibule, were present (Fig. 8). RhCG exhibited another important structural feature not present in Amt proteins, a pocket extending from the cytosolic aperture to the lateral exterior surface, termed a “shunt” pathway (38). This shunt pathway has an acidic residue in its intracellular surface and may serve as an alternative pathway for NH3 entry from the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayers.

Fig. 8.

Molecular structure of human RhCG showing key residues. A: ribbon structure model with lateral view. Twin, coplanar histidine residues, His185 and His344, function to stabilize NH3 transport and provide selectivity relative to other solutes, such as NH4, and are shown in ball-and-stick representation. Acidic residues in extracellular and intracellular vestibules, function in NH4+ attraction and stabilization (Glu166, Asp218, Asp278, and Glu329), and are shown in space-filling representation. B: cytoplasmic view of channel, demonstrating key NH4+-stabilizing acidic residues (Asp218, Asp278, and Glu329), coplanar histidine residues in pore channel, and representation of extracellular vestibule acidic residue (Glu166). Models were generated using BallView software, version 1.3.2 using human RhCG data (3HD6).

NKCC1.

NKCC1 is a Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter expressed in the basolateral region of intercalated cells in the OMCD and IMCD (31) and of IMCD cells (31, 49). However, peritubular bumetanide, an NKCC1/NKCC2 inhibitor, does not alter OMCD ammonia secretion; thus NKCC1 appears unlikely to mediate a quantitatively important role in OMCD ammonia secretion (101). In the IMCD, although NH4+ and K+ compete for a common binding site on NKCC1, pharmacologically inhibiting NKCC1 did not alter peritubular NH4+ uptake significantly (100). Thus NKCC1 appears unlikely to mediate a substantial role in renal ammonia secretion.

H+-K+-ATPase.

H+-K+-ATPase proteins are members of the P-type ATPase family. Various H+-K+-ATPase subunit isoforms and activities have been reported in the apical region of collecting duct cells. The majority of data demonstrating NH4+ transport by H+-K+-ATPase suggest NH4+ binds to and is transported at the K+ binding site. However, potassium deficiency increases expression of the colonic H+-K+-ATPase, which has been postulated to mediate increased NH4+ secretion via NH4+ binding and transport at the H+ binding site (82).

Aquaporins.

Aquaporins (AQP) comprise an extended family of proteins that facilitate water transport. Because both H2O and NH3 have similar molecular sizes and charge distribution, several studies have examined the role of aquaporins in NH3 transport. Importantly, some, but not all, aquaporins can transport ammonia (77). AQP1 was the first aquaporin shown to transport ammonia. Several studies have shown that expressing AQP1 in X. laevis oocytes increases NH3 transport (77, 83). However, not all studies have confirmed NH3 transport by AQP1 (45). AQP1 is present in the proximal tubule and in TDL; it may contribute to ammonia as well as water permeability in these segments. AQP3 is present in the basolateral membrane of collecting duct principal cells. When expressed in X. laevis oocytes, AQP3 transports NH3 (45). Whether AQP3 contributes to renal principal cell basolateral NH3 transport has not been determined. AQP8 is expressed in intracellular sites in the proximal tubule, CCD, and OMCD in the kidney, but not the plasma membrane (28). AQP8's specific intracellular site in mammalian cells has not been determined, but it localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane when expressed in yeast (96). AQP8's role in renal ammonia metabolism is unclear. Genetic deletion alters hepatic ammonia accumulation, renal excretion of infused ammonia, and intrarenal ammonia concentrations, but does not alter serum chloride concentration, urine ammonia concentration, or urine pH either under basal conditions or in response to acid-loading (115, 116). Thus aquaporins may be able to transport NH3, and are expressed at several renal epithelial sites in which NH3 transport remains incompletely characterized.

Summary

Renal ammonia transport is central to acid-base homeostasis. The previous paradigm of passive, lipid-phase NH3 diffusion and NH4+ trapping is being replaced by a model in which transporter-mediated movement of NH3 and NH4+ are fundamental components of renal ammonia physiology. In the proximal tubule, preferential apical NH4+ secretion involves specific transport involving NHE-3 and Ba2+-sensitive K+ channels, in the TAL ammonia reabsorption involves NH4+ transport by a variety of proteins, including NKCC2 and NHE-4, in the collecting duct Rhbg and Rhcg transport NH3, and in the IMCD basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase transports NH4+. Thus renal ammonia metabolism involves a complex interaction of multiple proteins that specifically transport the two molecularly distinct forms of ammonia, NH3 and NH4+. This complex interaction enables coordinated and highly regulated NH3 and NH4+ transport and likely contributes to the fine control of renal ammonia transport and excretion necessary for acid-base homeostasis.

GRANTS

The preparation and publication of this review was supported by funds from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-045788).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the numerous superb colleagues with whom we have been fortunate to collaborate on our projects examining the molecular mechanisms of ammonia transport.

Footnotes

The term ammonia is used to refer to the combination of NH3 and NH4+. When referring specifically to either of the two molecular forms of ammonia, we specifically state “NH3” or “NH4+.”

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambuhl PM, Amemiya M, Danczkay M, Lotscher M, Kaissling B, Moe OW, Preisig PA, Alpern RJ. Chronic metabolic acidosis increases NHE3 protein abundance in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F917–F925, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lotscher M, Kaissling B, Alpern RJ, Moe OW. Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 48: 1206–1215, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrade SLA, Dickmanns A, Ficner R, Einsle O. Crystal structure of the archaeal ammonium transporter Amt-1 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14994–14999, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aronson PS, Suhm MA, Nee J. Interaction of external H+ with the Na+-H+ exchanger in renal microvillus membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem 258: 6767–6711, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Atkins PW. Molecules in motion: ion transport and molecular diffusion. In: Physical Chemistry, edited by Atkins PW. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1978, p. 819–848 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Attmane-Elakeb A, Amlal H, Bichara M. Ammonium carriers in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F1–F9, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Attmane-Elakeb A, Boulanger H, Vernimmen C, Bichara M. Apical location and inhibition by arginine vasopressin of K+/H+ antiport of the medullary thick ascending limb of rat kidney. J Biol Chem 272: 25668–25677, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Attmane-Elakeb A, Mount DB, Sibella V, Vernimmen C, Hebert SC, Bichara M. Stimulation by in vivo and in vitro metabolic acidosis of expression of rBSC-1, the Na+-K+ (NH4+)-2Cl− cotransporter of the rat medullary thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem 273: 33681–33691, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Attmane-Elakeb A, Sibella V, Vernimmen C, Belenfant X, Hebert SC, Bichara M. Regulation by glucocorticoids of expression and activity of rBSC1, the Na+-K+ (NH4+)-2Cl− cotransporter of medullary thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem 275: 33548–33553, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bakouh N, Benjelloun F, Hulin P, Brouillard F, Edelman A, Cherif-Zahar B, Planelles G. NH3 is involved in the NH4+ transport induced by the functional expression of the human Rh C glycoprotein. J Biol Chem 279: 15975–15983, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bell JM, Feild AL. The distribution of ammonia between water and chloroform. J Am Chem Soc 33: 940–943, 1911 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bishop JM, Verlander JW, Lee HW, Nelson RD, Weiner AJ, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Role of the Rhesus glycoprotein, Rh B Glycoprotein, in renal ammonia excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1065–F1077, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biver S, Belge H, Bourgeois S, Van Vooren P, Nowik M, Scohy S, Houillier P, Szpirer J, Szpirer C, Wagner CA, Devuyst O, Marini AM. A role for Rhesus factor Rhcg in renal ammonium excretion and male fertility. Nature 456: 339–343, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blake-Palmer KG, Karet FE. Cellular physiology of the renal H+ATPase. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 433–438, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blanchard A, Eladari D, Leviel F, Tsimaratos M, Paillard M, Podevin RA. NH4+ as a substrate for apical and basolateral Na+-H+ exchangers of thick ascending limbs of rat kidney: evidence from isolated membranes. J Physiol (Lond) 506: 689–698, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bourgeois S, Meer LV, Wootla B, Bloch-Faure M, Chambrey R, Shull GE, Gawenis LR, Houillier P. NHE4 is critical for the renal handling of ammonia in rodents. J Clin Invest 120: 1895–1904, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown ACN, Hallouane D, Mawby WJ, Karet FE, Saleem MA, Howie AJ, Toye AM. RhCG is the major putative ammonia transporter expressed in human kidney and RhBG is not expressed at detectable levels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1279–F1290, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown D, Paunescu TG, Breton S, Marshansky V. Regulation of the V-ATPase in kidney epithelial cells: dual role in acid-base homeostasis and vesicle trafficking. J Exp Biol 212: 1762–1772, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chambrey R, Goossens D, Bourgeois S, Picard N, Bloch-Faure M, Leviel F, Geoffroy V, Cambillau M, Colin Y, Paillard M, Houillier P, Cartron JP, Eladari D. Genetic ablation of Rhbg in mouse does not impair renal ammonium excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1281–F1290, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chambrey R, John PL, Eladari D, Quentin F, Warnock DG, Abrahamson DR, Podevin RA, Paillard M. Localization and functional characterization of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE4 in rat thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F707–F717, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cherif-Zahar B, Durand A, Schmidt I, Matic I, Merrick M, Matassi G. Evolution and functional characterisation of the RH50 gene from the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol 189: 9090–9100, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheval L, Morla L, Elalouf JM, Doucet A. Kidney collecting duct acid-base “regulon”. Physiol Genomics 27: 271–281, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Codina J, Dubose TD., Jr Molecular regulation and physiology of the H+,K+-ATPases in kidney. Semin Nephrol 26: 345–351, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curthoys NP, Watford M. Regulation of glutaminase activity and glutamine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 15: 133–159, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curthoys NP, Lowry OH. The distribution of glutaminase isoenzymes in the various structures of the nephron in normal, acidotic, and alkalotic rat kidney. J Biol Chem 248: 162–168, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DuBose TD, Good DW, Hamm LL, Wall SM. Ammonium transport in the kidney: new physiological concepts and their clinical implications. J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1193–1203, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eladari D, Cheval L, Quentin F, Bertrand O, Mouro I, Cherif-Zahar B, Cartron JP, Paillard M, Doucet A, Chambrey R. Expression of RhCG, a new putative NH3/NH4+ transporter, along the rat nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1999–2008, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elkjar ML, Nejsum LN, Gresz V, Kwon TH, Jensen UB, Frøkiær J, Nielsen S. Immunolocalization of aquaporin-8 in rat kidney, gastrointestinal tract, testis, and airways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1047–F1057, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Falk KG. Transference numbers of electrolytes in aqueous solutions. In: International Critical Tables of Numerical Data, Physics, Chemistry and Technology, edited by Washburn EW. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1929, p. 309–311 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Flessner MF, Mejia R, Knepper MA. Ammonium and bicarbonate transport in isolated perfused rodent long-loop thin descending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F388–F396, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ginns SM, Knepper MA, Ecelbarger CA, Terris J, He X, Coleman RA, Wade JB. Immunolocalization of the secretory isoform of Na-K-Cl cotransporter in rat renal intercalated cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2533–2542, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Good DW. Effects of potassium on ammonia transport by medullary thick ascending limb of the rat. J Clin Invest 80: 1358–1365, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Good DW. Active absorption of NH4+ by rat medullary thick ascending limb: inhibition by potassium. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F78–F87, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Good DW. Regulation of acid-base transport in the rat thick ascending limb. Am J Kidney Dis 14: 262–266, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Good DW. Adaptation of HCO3− and NH4+ transport in rat MTAL: effects of chronic metabolic acidosis and Na+ intake. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 258: F1345–F1353, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Good DW. Ammonium transport by the thick ascending limb of Henle's loop. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 623–647, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Good DW, Burg MB. Ammonia production by individual segments of the rat nephron. J Clin Invest 73: 602–610, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gruswitz F, Chaudhary S, Ho JD, Schlessinger A, Pezeshki B, Ho CM, Sali A, Westhoff CM, Stroud RM. Function of human Rh based on structure of RhCG at 2.1 ä. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 9638–9643, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gumz ML, Lynch IJ, Greenlee MM, Cain BD, Wingo CS. The renal-ATPases: physiology, regulation, structure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F12–F21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hamm LL, Simon EE. Roles and mechanisms of urinary buffer excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F595–F605, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han KH, Croker BP, Clapp WL, Werner D, Sahni M, Kim J, Kim HY, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Expression of the ammonia transporter, Rh C Glycoprotein, in normal and neoplastic human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2670–2679, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Han KH, Mekala K, Babida V, Kim HY, Handlogten ME, Verlander JW, Weiner ID. Expression of the gas transporting proteins, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein, in the murine lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L153–L163, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Han KH, Lee SY, Kim WY, Shin JA, Kim J, Weiner ID. Expression of the ammonia transporter family members, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein, in the developing rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F187–F198, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Handlogten ME, Hong SP, Zhang L, Vander AW, Steinbaum ML, Campbell-Thompson M, Weiner ID. Expression of the ammonia transporter proteins, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein, in the intestinal tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G1036–G1047, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holm LM, Jahn TP, Moller AL, Schjoerring JK, Ferri D, Klaerke DA, Zeuthen T. NH3 and NH4+ permeability in aquaporin-expressing Xenopus oocytes. Pflügers Arch 450: 415–428, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. ten Hoopen F, Cuin TA, Pedas P, Hegelund JN, Shabala S, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Competition between uptake of ammonium and potassium in barley and Arabidopsis roots: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. J Exp Bot 61: 2303–2315, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang CH, Peng J. Evolutionary conservation and diversification of Rh family genes and proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15512–15517, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jorgensen PL. Sodium and potassium ion pump in kidney tubules. Physiol Rev 60: 864–917, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaplan MR, Plotkin MD, Brown D, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the mouse Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, mBSC2, in the terminal inner medullary collecting duct, the glomerular and extraglomerular mesangium, and the glomerular afferent arteriole. J Clin Invest 98: 723–730, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Karet FE. Mechanisms in hyperkalemic renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 251–254, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Khademi S, O'Connell J, III, Remis J, Robles-Colmenares Y, Miercke LJ, Stroud RM. Mechanism of ammonia transport by Amt/MEP/Rh: structure of AmtB at 1.35 A. Science 305: 1587–1594, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kikeri D, Sun A, Zeidel ML, Hebert SC. Cell membranes impermeable to NH3. Nature 339: 478–480, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim HY, Verlander JW, Bishop JM, Cain BD, Han KH, Igarashi P, Lee HW, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Basolateral expression of the ammonia transporter family member, Rh C Glycoprotein, in the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F545–F555, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim HY, Baylis C, Verlander JW, Han KH, Reungjui S, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Effect of reduced renal mass on renal ammonia transporter family, Rh C glycoprotein and Rh B glycoprotein, expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1238–F1247, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim YH, Verlander JW, Matthews SW, Kurtz I, Shin WK, Weiner ID, Everett LA, Green ED, Nielsen S, Wall SM. Intercalated cell H+/OH− transporter expression is reduced in Slc26a4 null mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1262–F1272, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kinsella JL, Aronson PS. Interaction of NH4+ and Li+ with the renal microvillus membrane Na+-H+ exchanger. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 241: C220–C226, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Knepper MA. NH4+ transport in the kidney. Kidney Int 40: S95–S102, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Knepper MA, Good DW, Burg MB. Mechanism of ammonia secretion by cortical collecting ducts of rabbits. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 247: F729–F738, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kurtz I, Balaban RS. Ammonium as a substrate for Na+-K+-ATPase in rabbit proximal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 250: F497–F502, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kwon TH, Fulton C, Wang W, Kurtz I, Frøkiær J, Aalkjaer C, Nielsen S. Chronic metabolic acidosis upregulates rat kidney Na-HCO cotransporters NBCn1 and NBC3 but not NBC1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F341–F351, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lee HW, Verlander JW, Bishop JM, Igarashi P, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Collecting duct-specific Rh C Glycoprotein deletion alters basal and acidosis-stimulated renal ammonia excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1364–F1375, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee HW, Verlander JW, Bishop JM, Nelson RD, Handlogten ME, Weiner ID. Effect of intercalated cell-specific Rh C Glycoprotein deletion on basal and metabolic acidosis-stimulated renal ammonia excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F369–F379, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee S, Lee HJ, Yang HS, Thornell IM, Bevensee MO, Choi I. Na/bicarbonate cotransporter NBCn1 in the kidney medullary thick ascending limb cell line is upregulated under acidic conditions and enhances ammonium transport. Exp Physiol 95: 926–937, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li X, Jayachandran S, Nguyen HH, Chan MK. Structure of the Nitrosomonas europaea Rh protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19279–19284, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lim SW, Ahn KO, Kim WY, Han DH, Li C, Ghee JY, Han KH, Kim HY, Handlogten ME, Kim J, Yang CW, Weiner ID. Expression of ammonia transporters, Rhbg and Rhcg, in chronic cyclosporine nephropathy in rats. Nephron Exp Nephrol 110: e49–e58, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu Z, Huang CH. The mouse Rhl1 and Rhag genes: sequence, organization, expression, and chromosomal mapping. Biochem Genet 37: 119–138, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu Z, Chen Y, Mo R, Hui Cc, Cheng JF, Mohandas N, Huang CH. Characterization of human RhCG and mouse Rhcg as novel nonerythroid Rh glycoprotein homologues predominantly expressed in kidney and testis. J Biol Chem 275: 25641–25651, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu Z, Peng J, Mo R, Hui Cc, Huang CH. Rh type B glycoprotein is a new member of the Rh superfamily and a putative ammonia transporter in mammals. J Biol Chem 276: 1424–1433, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lopez C, Metral S, Eladari D, Drevensek S, Gane P, Chambrey R, Bennett V, Cartron JP, Van Kim C, Colin Y. The ammonium transporter RhBG: requirement of a tyrosine-based signal and ankyrin-G for basolateral targeting and membrane anchorage in polarized kidney epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 8221–8228, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ludewig U, von Wiren N, Frommer WB. Uniport of NH4+ by the root hair plasma membrane ammonium transporter LeAMT1;1. J Biol Chem 277: 13548–13555, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ludewig U. Electroneutral ammonium transport by basolateral Rhesus B glycoprotein. J Physiol 559: 751–759, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lupo D, Li XD, Durand A, Tomizaki T, Cherif-Zahar B, Matassi G, Merrick M, Winkler FK. The 1.3-A resolution structure of Nitrosomonas europaea Rh50 and mechanistic implications for NH3 transport by Rhesus family proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19303–19308, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mak DO, Dang B, Weiner ID, Foskett JK, Westhoff CM. Characterization of transport by the kidney Rh glycoproteins, RhBG and RhCG. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F297–F305, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marini AM, Matassi G, Raynal V, Andre B, Cartron JP, Cherif-Zahar B. The human Rhesus-associated RhAG protein and a kidney homologue promote ammonium transport in yeast. Nat Genet 26: 341–344, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mouro-Chanteloup I, Cochet S, Chami M, Genetet S, Zidi-Yahiaoui N, Engel A, Colin Y, Bertrand O, Ripoche P. Functional reconstitution into liposomes of purified human RhCG ammonia channel. PLoS ONE 5: e8921, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mudry B, Guy RH, Delgado-Charro MB. Transport numbers in transdermal iontophoresis. Biophys J 90: 2822–2830, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Musa-Aziz R, Chen LM, Pelletier MF, Boron WF. Relative CO2/NH3 selectivities of AQP1, AQP4, AQP5, AmtB, and RhAG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5406–5411, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nagami GT. Luminal secretion of ammonia in the mouse proximal tubule perfused in vitro. J Clin Invest 81: 159–164, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nagami GT. Effect of bath and luminal potassium concentration on ammonia production and secretion by mouse proximal tubules perfused in vitro. J Clin Invest 86: 32–39, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nagami GT. Ammonia production and secretion by S3 proximal tubule segments from acidotic mice: role of ANG II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F707–F712, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nagami GT. Role of angiotensin II in the enhancement of ammonia production and secretion by the proximal tubule in metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F874–F880, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nakamura S, Amlal H, Galla JH, Soleimani M. NH4+ secretion in inner medullary collecting duct in potassium deprivation: role of colonic H+-K+-ATPase. Kidney Int 56: 2160–2167, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nakhoul NL, Hering-Smith KS, Abdulnour-Nakhoul SM, Hamm LL. Transport of NH3/NH in oocytes expressing aquaporin-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F255–F263, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nakhoul NL, DeJong H, Abdulnour-Nakhoul SM, Boulpaep EL, Hering-Smith K, Hamm LL. Characteristics of renal Rhbg as an NH4+ transporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F170–F181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Occleshaw VJ. The distribution of ammonia between chloroform and water at 25°C. J Chem Soc 1436–1437, 1931 [Google Scholar]

- 86. Odgaard E, Jakobsen JK, Frische S, Praetorius J, Nielsen S, Aalkjaer C, Leipziger J. Basolateral Na+-dependent HCO3− transporter NBCn1-mediated HCO3− influx in rat medullary thick ascending limb. J Physiol (Lond) 555: 205–218, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Quentin F, Eladari D, Cheval L, Lopez C, Goossens D, Colin Y, Cartron JP, Paillard M, Chambrey R. RhBG and RhCG, the putative ammonia transporters, are expressed in the same cells in the distal nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 545–554, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ripoche P, Bertrand O, Gane P, Birkenmeier C, Colin Y, Cartron JP. Human Rhesus-associated glycoprotein mediates facilitated transport of NH3 into red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17222–17227, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sartorius OW, Roemmelt JC, Pitts RF. The renal regulation of acid-base balance in man. IV. The nature of the renal compensations in ammonium chloride acidosis. J Clin Invest 28: 423–439, 1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Seshadri RM, Klein JD, Kozlowski S, Sands JM, Kim YH, Handlogten ME, Verlander JW, Weiner ID. Renal expression of the ammonia transporters, Rhbg and Rhcg, in response to chronic metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F397–F408, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Seshadri RM, Klein JD, Smith T, Sands JM, Handlogten ME, Verlander JW, Weiner ID. Changes in the subcellular distribution of the ammonia transporter Rhcg, in response to chronic metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1443–F1452, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Simon E, Martin D, Buerkert J. Contribution of individual superficial nephron segments to ammonium handling in chronic metabolic acidosis in the rat. Evidence for ammonia disequilibrium in the renal cortex. J Clin Invest 76: 855–864, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Simon EE, Merli C, Herndon J, Cragoe EJ, Jr, LL Hamm. Determinants of ammonia entry along the rat proximal tubule during chronic metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F1104–F1110, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Simon EE, Merli C, Herndon J, Cragoe EJ, Jr, LL Hamm. Effects of barium and 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride on proximal tubule ammonia transport. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F36–F39, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Singh SK, Binder HJ, Geibel JP, Boron WF. An apical permeability barrier to NH3/NH4+ in isolated, perfused colonic crypts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11573–11577, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Soria LR, Fanelli E, Altamura N, Svelto M, Marinelli RA, Calamita G. Aquaporin 8-facilitated mitochondrial ammonia transport. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Taylor L, Curthoys NP. Glutamine metabolism: role in acid-base balance. Biochem Mol Biol Education 32: 291–304, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Verlander JW, Miller RT, Frank AE, Royaux IE, Kim YH, Weiner ID. Localization of the ammonium transporter proteins, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein, in the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F323–F337, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Waisbren SJ, Geibel JP, Modlin IM, Boron WF. Unusual permeability properties of gastric gland cells. Nature 368: 332–335, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wall SM. Ouabain reduces net acid secretion and increases pHi by inhibiting NH4+ uptake on rat tIMCD Na+-K+-ATPase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F857–F868, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Wall SM, Fischer MP. Contribution of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) to transepithelial transport of H+, NH4+, K+, and Na+ in rat outer medullary collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 827–835, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wall SM, Fischer MP, Kim GH, Nguyen BM, Hassell KA. In rat inner medullary collecting duct, NH4+ uptake by the Na,K-ATPase is increased during hypokalemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F91–F102, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wall SM, Koger LM. NH4+ transport mediated by Na+-K+-ATPase in rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F660–F670, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Weidinger K, Neuhauser B, Gilch S, Ludewig U, Meyer O, Schmidt I. Functional and physiological evidence for a rhesus-type ammonia transporter in Nitrosomonas europaea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273: 260–267, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Weiner ID. The Rh gene family and renal ammonium transport. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13: 533–540, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Weiner ID, Hamm LL. Molecular mechanisms of renal ammonia transport. Annu Rev Physiol 69: 317–340, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Weiner ID, Miller RT, Verlander JW. Localization of the ammonium transporters, Rh B Glycoprotein and Rh C Glycoprotein in the mouse liver. Gastroenterology 124: 1432–1440, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Weiner ID, Verlander JW. Molecular physiology of the Rh ammonia transport proteins. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 471–477, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Weinstein AM. Ammonia transport in a mathematical model of rat proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F237–F248, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Weinstein AM, Krahn TA. A mathematical model of rat ascending Henle limb. II. Epithelial function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F525–F542, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Westhoff CM, Ferreri-Jacobia M, Mak DO, Foskett JK. Identification of the erythrocyte Rh-blood group glycoprotein as a mammalian ammonium transporter. J Biol Chem 277: 12499–12502, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Westhoff CM, Siegel DL, Burd CG, Foskett JK. Mechanism of genetic complementation of ammonium transport in yeast by human erythrocyte Rh-associated glycoprotein (RhAG). J Biol Chem 279: 17443–17448, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wilcox CS, Granges F, Kirk G, Gordon D, Giebisch G. Effects of saline infusion on titratable acid generation and ammonia secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 247: F506–F519, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wright PA, Knepper MA. Phosphate-dependent glutaminase activity in rat renal cortical and medullary tubule segments. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F961–F970, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Yang B, Song Y, Zhao D, Verkman AS. Phenotype analysis of aquaporin-8 null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1161–C1170, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yang B, Zhao D, Solenov E, Verkman AS. Evidence from knockout mice against physiologically significant aquaporin 8-facilitated ammonia transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C417–C423, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Yip KP, Kurtz I. NH3 permeability of principal cells and intercalated cells measured by confocal fluorescence imaging. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F545–F550, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Zheng L, Kostrewa D, Berneche S, Winkler FK, Li XD. The mechanism of ammonia transport based on the crystal structure of AmtB of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17090–17095, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]