Abstract

To establish the role of vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin in the regulation of endothelial cell functions, we investigated the effect of phosphorylation of a VE-cadherin site sought to be involved in p120-catenin binding on vascular permeability and endothelial cell migration. To this end, we introduced either wild-type VE-cadherin or Y658 phosphomimetic (Y658E) or dephosphomimetic (Y658F) VE-cadherin mutant constructs into an endothelial cell line (rat fat pad endothelial cells) lacking endogenous VE-cadherin. Remarkably, neither wild-type- nor Y658E VE-cadherin was retained at cell-cell contacts because of p120-catenin preferential binding to N-cadherin, resulting in the targeting of N-cadherin to cell-cell junctions and the exclusion of VE-cadherin. However, Y658F VE-cadherin was able to bind p120-catenin and to localize at adherence junctions displacing N-cadherin. This resulted in an enhanced barrier function and a complete abrogation of Rac1 activation and lamellipodia formation, thereby inhibiting cell migration. These findings demonstrate that VE-cadherin, through the regulation of Y658 phosphorylation, competes for junctional localization with N-cadherin and controls vascular permeability and endothelial cell migration.

Keywords: cell migration, permeability, adherens junction, vascular endothelial

angiogenesis is a multistep process triggered by endothelial cell (EC) proliferation and migration followed by an assembly into a new vascular structure. Whereas ECs are contact inhibited in the quiescent state, they undergo active proliferation and migration upon angiogenic stimuli while maintaining barrier function. This coordination is regulated by adhesion molecules in cell-cell junctions whose assembly and disassembly are tightly controlled and critically important for a variety of endothelial functions. Among those molecules, vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, a transmembrane homophilic adhesion receptor, plays a central role in integrating spatial signals into cell behavior. Although VE-cadherin has been regarded as primarily important for mediating intercellular adhesion and maintaining vascular integrity, recent studies began to reveal other aspects of VE-cadherin's biology (11, 39). In fact, homozygous knockout of VE-cadherin (Cdh5) in mice leads to significant defects in vascular remodeling and embryonic lethality at embryonic day 9.5 because of vessel collapse, regression, and extensive hemorrhages (6).

EC adhesion is a tightly controlled process in which correct targeting and stabilization of the VE-cadherin complex at cell-cell contacts are particularly important. VE-cadherin interacts, via its cytoplasmic tail, with three proteins of the armadillo family, called p120-catenin (p120), β-catenin, and plakoglobin. A modification of the molecular organization and intracellular signaling of junction proteins have complex effects on vascular homeostasis. β-Catenin directly associates with α-catenin, which is able to interact with F-actin, thereby tethering the cadherin complex to cytoskeletal actin (1). Src-induced phosphorylation of Y658 or Y731 of VE-cadherin prevents the binding of p120 and β-catenin, respectively, which increases endothelial permeability and is sufficient to maintain cells in a mesenchymal state (5, 31). Among these catenins, p120 acts to regulate cadherin stability and internalization, thereby critically important for cell-cell adhesion, endothelial homeostasis, and vascular development (9, 30). The depletion of p120 results in the elimination of multiple cadherins and the complete loss of cell-cell adhesion (9). Recent studies demonstrate that p120 can control a variety of cell functions by regulating Rho GTPase activities through both cadherin-dependent and -independent manners (4). Moreover, signaling from adhesion receptor to small GTPases is required for junction assembly, disassembly, and maintenance that involve dynamic actin reorganization (41). In ECs, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling is closely related with the functional modulation of VE-cadherin-based junctions. VEGF increases vascular permeability by inducing VE-cadherin internalization, whereas VE-cadherin influences VEGF-induced Erk activation and shear stress response (21, 38). This raises the possibility that cadherin signaling sensing spatial information is capable of modulating growth factor signaling to better accommodate the environment and reflect to cell behaviors.

In this study, therefore, we hypothesized that the regulation of Y658 phosphorylation is not only crucial to VE-cadherin's adhesive function but also to the induction of cell motility via control of Rac1 activity that drives directional cell migration. Using an EC line that lacks endogenous VE-cadherin, we investigated the specific contribution of VE-cadherin phosphorylation at Y658 to endothelial adhesive and migratory functions. We find that dephosphorylation of Y658 VE-cadherin results in increased association with p120, which in turn displaces N-cadherin and stabilizes the VE-cadherin complex at cell-cell contacts. While this leads to enhanced endothelial barrier function, cell motility is remarkably suppressed, and there is a marked reduction of lamellipodia formation resulting from impaired Rac1 activation at the leading edge. In contrast, phosphorylation of Y658 is sufficient for Rac1 activation and lamellipodia formation at the migrating front, thereby promoting cell migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Antibodies against the following antigens were commercially obtained: VE-cadherin (Cell signaling Technology), N-cadherin (BD Transduction Laboratories), p120-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), green fluorescent protein (GFP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rac1 (Cytoskeleton), and Rac1-GTP (New East Biosciences). Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) were purchased from Invitrogen and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively.

Construction of cell lines expressing GFP-tagged VE-cadherin.

Rat fat pad ECs (RFPECs) were maintained in our laboratory (10, 14, 27). cDNA of human VE-cadherin fused in-frame with GFP at the COOH-terminus (VE-cadherin-GFP) was a kind gift from Dr. Sunil K. Shaw (Women and Infants' Hospital, Providence, RI) (34). VE-cadherin-GFP was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). A tyrosine to glutamic acid (Y to E) mutation or a tyrosine to phenylalanine (Y to F) mutation at VE-cadherin Y658 site (Y658E or Y658F, respectively) was introduced using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Plasmids were transfected into RFPECs using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche) following the manufacture's instruction. RFPECs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Lonza) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 250 ng/ml amphotericin B, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. To establish stable cell lines, resistant cells against 500 μg/ml G418 were pooled and sorted by flow cytometry based on GFP fluorescence.

Lentivirus vector construct and transduction of ECs.

Each VE-cadherin-GFP construct [wild-type (WT), Y658E, and Y658F] was subcloned into pLVX-IRES-puro lentiviral expression vector (Clontech). Lentivirus packaging and envelope vectors, pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-Rev, and pMD2.G, were purchased from Addgene. These plasmids were cotransfected into 293T cells to produce a recombinant lentivirus stock.

Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) on a six-well plate were cultured in EGM-2 medium (Lonza) to 50–60% confluent. Lentivirus was added to the cells with 5 μg/ml polybrene, and the six-well plate was centrifuged at 2,300 rpm for 90 min at 37°C, following an 8-h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2-95% room air. To obtain stable infected cells, the cells were selected with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin for 4 days and maintained with 0.1 μg/ml puromycin.

Immunofluorescence.

Immunocytochemistry was performed with a standard procedure. Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), permeabilized in 0.1% Triton-X in PBS for 5 min at RT, and blocked in Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min at RT. Coverslips were incubated in primary antibody at 4°C overnight, washed three times in PBS and then incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h at RT. Then the coverslips were washed three times in PBS and mounted using Fluoro-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Images were captured using Zeiss 510 laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Permeability assay.

Transendothelial electrical resistance, an index of EC barrier function, was measured in real time using an electric cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system (ECIS 1600, Applied BioPhysics) (28). Cells were plated on sterile eight-chambered gold-plated electrode arrays (8W10E plus) precoated with fibronectin and grown to full confluence. The electrode arrays were mounted on the ECIS system within an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2-95% room air) and connected to its recorder device. Monolayer resistance was recorded at 15 kHz for 8 h in 5-min intervals.

Cell migration assay.

Cells in six-well plate were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. A scratch was made using a 200-μl tip, and the cells were allowed to migrate for 16 h. Pictures were taken right after making a scratch and at the end of migration. The migration rate was then determined by analyzing the relative gap closure during the period using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software.

For time-lapse imaging, cells on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes were cultured to reach full confluency. A scratch was made using a 200-μl tip, and the cells were allowed to migrate in normal growth medium for 2 h. Time-lapse motion pictures at the leading edge of the migrating cells were captured during the period using PerkinElmer UltraVIEWVoX confocal microscopy, and the movies were constructed by Volocity software (PerkinElmer).

Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1× complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. For immunoprecipitation assay, total cell lysates were harvested with HEPES lysis buffer with NP-40 containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, and 1× complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) and incubated with the appropriate antibody and Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen). The beads were washed four times with PBS, boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

RNA interference.

Rat N-cadherin (CDH2) Stealth small interfering RNA (siRNA) and Stealth RNAi siRNA negative control were purchased from Invitrogen. siRNA was delivered into 50% confluent cells using TransPass R2 transfection reagent (New England Biolabs), following the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, the cells were used for experiments.

Rac1 activity assay.

Rac1 pull-down assay was performed using Rac1 activation assay biochem kit (Cytoskeleton), following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells were serum starved in 0.5% FBS-DMEM for 24 h before assay. Upon IGF stimulation for 10 min, the cells were lysed on ice with cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. p21-Activated kinase-conjugated protein beads were incubated with the cell lysates at 4°C for 1 h before being washed three times and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Eluted proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Rac1 antibody. In addition, basal Rac1 activity in normal growth medium condition (i.e., without serum starvation) was also measured in the same way.

Immunocytochemistry for detecting active Rac1 was conducted using the antibody against Rac1-GTP. Cells were rinsed quickly with 37°C PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at RT, followed by blocking with 5% FBS in PBS-Triton solution, containing 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, for 1 h at RT. Coverslips were incubated in the primary antibody against Rac1-GTP in PBS-Triton solution at 4°C overnight, washed three times in PBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h at RT. The coverslips were then washed three times in PBS and mounted using Fluoro-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Images were captured using Zeiss 510 laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Statistics.

Data were expressed as means ± SD. Comparison between groups were performed with a two-tailed Student's t-test. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Dephosphorylation of Y658 is essential for VE-cadherin to form adherens junctions.

To test the hypothesis that the phosphorylation of VE-cadherin Y658 is important for modulating EC functions, we have generated EC lines expressing either a WT VE-cadherin or a phopshomimetic (Y658E) or a dephosphomimetic (Y658F) mutant. The lines were established in RFPECs that have very low levels of endogenous VE-cadherin. In nontransfected RFPECs, VE-cadherin expression was not detectable, and N-cadherin localized at intercellular junctions (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, the RFPEC line expressing WT VE-cadherin demonstrated nearly a total absence of the protein from cell-cell junctions with most of the expressed proteins found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). The junctional localization of Y658E VE-cadherin was either absent or weak with a broader and fuzzy pattern depending on the area of observation; instead, significant cytoplasmic distribution of Y658E VE-cadherin was observed (Fig. 1C). In contrast, cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin mutant demonstrated a distinct localization of the protein at cell-cell contacts (Fig. 1D). Intriguingly, N-cadherin was expressed in cell-cell junctions in untransfected RFPECs, as well as in RFPEC lines expressing WT or Y658E mutant but not in cells expressing the Y658F mutant (Fig. 1, A–D). This suggests that VE-cadherin competes for junctional localization with N-cadherin, and this regulation involves the phosphorylation of VE-cadherin Y658.

Fig. 1.

Y658F mutants localize at adherens junctions. Rat fat pad endothelial cells (RFPECs) expressing wild-type vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin (VEC-WT), Y658E, or Y658F mutants were fixed, and the expression patterns of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged VE-cadherin and N-cadherin were determined by immunofluorescence. Cells were stained for VE-cadherin (red) and N-cadherin (blue). A: in RFPECs, endogenous VE-cadherin was not detected and N-cadherin formed cell-cell contacts. B: VEC-WT did not concentrate at cell-cell junctions. C and D: Y658F mutants clearly localized at cell-cell junctions, whereas Y658E mutants did not homogenously line on the cell borders with increased cytoplasmic distribution. Scale bars = 10 μm. E: VEC-WT was proteolytically degraded in RFPECs. Total cell lysates of confluent RFPECs expressing VEC-WT, Y658E, or Y658F mutants were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. The antibody against VE-cadherin recognizes the cytoplasmic tail of VE-cadherin.

Western blot analysis using an antibody against the cytoplasmic domain of VE-cadherin demonstrated the presence of a band at around 45 kDa (Fig. 1E). This protein fragment corresponds in size to the part of the cytoplasmic domain of VE-cadherin-GFP and can be also detected by an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 1E). With the use of mass spetctrometry, the fragment was identified as a cytoplasmic tail of VE-cadherin, suggesting proteolytic degradation of WT VE-cadherin. In contrast, both Y658E and Y658F VE-cadherin mutants were expressed as full-length proteins. Since Y658E VE-cadherin is not cleaved despite its cytoplasmic localization, an exclusion from cell-cell contacts alone is not sufficient for VE-cadherin degradation.

The RFPEC is an atypical EC line with respect to VE-cadherin expression; therefore, we confirmed the expression pattern of VE-cadherin mutants using primary ECs. As expected, WT VE-cadherin distributed at cell-cell contacts in HUVECs, indicating that the WT VE-cadherin construct containing GFP behaves similar to endogenous VE-cadherin (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B; note: all supplemental material may be found posted with the online version of this article) (34, 37). Even in the presence of endogenous VE-cadherin, the distribution pattern of VE-cadherin mutants recapitulated the results obtained from RFPECs. While Y658F VE-cadherin strictly localized at cell-cell contacts, Y658E VE-cadherin distributed in the cytoplasm with attenuated junctional retention (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). It appears that total VE-cadherin expression is tightly controlled in HUVECs where lentivirus-mediated transduction of VE-cadherin decreased endogenous VE-cadherin expression levels as described previously (supplemental Fig. 1E) (18).

Cytoplasmic distribution and degradation of VE-cadherin observed in cells expressing WT VE-cadherin suggests that the presence of N-cadherin at cell-cell contacts prevents VE-cadherin's junctional localization and leads to the degradation in RFPECs. To test this hypothesis, siRNA was used to suppress N-cadherin expression. The knockdown of N-cadherin in WT VE-cadherin expressing RFPECs led to the restoration of full-length VE-cadherin expression (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, WT VE-cadherin assumed junctional localization and was associated with p120 (Fig. 2, B and C). This suggests that N-cadherin is capable of controlling VE-cadherin junctional localization and proteolytic degradation. Interestingly, cells that still express N-cadherin at cell-cell contacts after N-cadherin siRNA treatment did not show junctional VE-cadherin staining, implying that the presence of the two cadherins at cell-cell junctions is mutually exclusive (Fig. 2B, arrows).

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of N-cadherin restores VE-cadherin localization at adherens junctions. A: RFPECs expressing VEC-WT was treated with N-cadherin small interfering RNA (siRNA). Forty eight hours later, total cell lysates were harvested with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with VE-cadherin antibody that recognizes the cytoplasmic tail of VE-cadherin. Y658F VE-cadherin was loaded as a control. B and C: RFPECs expressing VEC-WT were treated with N-cadherin siRNA and fixed, and the expression patterns of GFP-tagged VE-cadherin, N-cadherin, and p120-catenin were determined by immunofluorescence. Cells were stained for VE-cadherin (red), N-cadherin (blue; B), and p120-catenin (blue; C). Scale bars = 10 μm.

Phosphorylation status of VE-cadherin Y658 modulates endothelial permeability.

Regulation of endothelial permeability is largely controlled by VE-cadherin-mediated opening of paracellular junctions. To investigate the physiological significance of VE-cadherin Y658 phosphorylation for the endothelial barrier function, we measured monolayer permeability using the electrical cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system. In the confluent and quiescent monolayer, cells expressing Y658E VE-cadherin showed a significant decrease in transendothelial impedance (increased permeability) compared with WT VE-cadherin or Y658F VE-cadherin-expressing cells (Fig. 3, A and B). The presence of N-cadherin in RFPEC cell-cell junctions can contribute to the barrier function, thereby confounding the effect of VE-cadherin mutations. To surmount the situation, we employed N-cadherin siRNA to further analyze the precise function of VE-cadherin phosphorylation on endothelial permeability. Following N-cadherin knockdown, the impedance of nontransfected RFPECs was dramatically decreased as expected (Fig. 3, B and D). Y658F VE-cadherin-expressing RFPECs still showed high transendothelial resistance, indicating N-cadherin has no effect on the maintenance of permeability in these cells. However, the resistance was low in Y658E VE-cadherin-expressing RFPECs, whereas it was unchanged in WT VE-cadherin-expressing RFPECs (Fig. 3, C and D). In the latter case, the likely explanation is the replacement of N-cadherin-based junctions with WT VE-cadherin-based junctions since in the absence of the former, the latter is no longer degraded and can localize at cell-cell contacts (Fig. 2, A and B). This conclusion is supported by the observation of very low transendothelial resistance in untransfected RFPECs following N-cadherin knockdown.

Fig. 3.

Y658F mutation of VE-cadherin keeps cell monolayer integrity. Endothelial monolayer permeability was evaluated with the electric cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system. Impedance was measured every 5 min for 8 h after the cells became fully confluent. Representative data (A and C) and quantification of 6 separate measurements of ECIS (B and D) are shown. A and B: Y658E mutation decreased the cell monolayer impedance. C and D: after cells were treated with N-cadherin siRNA, cell monolayer impedance was measured. Note that Y658F mutant maintains high impedance. Data are means ± SD for n = 6. *P < 0.05 by t-test.

In the attempt to reproduce these results in primary cells, we transduced HUVECs with Y658E or Y658F VE-cadherin mutants. Although we observed a similar tendency, it did not reach significant statistical difference (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). This is likely due to the lower expression levels of mutant VE-cadherin compared with endogenous VE-cadherin, which masked the effects of mutant VE-cadherin (supplemental Fig. 1E). To avoid the confounding effects arising from endogenous VE-cadherin, we hereafter used RFPECs for further functional analyses of VE-cadherin mutants.

p120 binding to VE-cadherin requires dephosphorylation of Y658.

p120 plays a crucial role in regulating VE-cadherin stability at adherens junctions. We therefore asked whether the competition between N- and VE-cadherin for junctional localization is mediated by a preferential binding of p120 to either cadherin. As shown in Fig. 4A, p120 was expressed at cell junctions in RFPECs, presumably interacting with N-cadherin. This localization pattern was not altered by the introduction of WT or Y658E VE-cadherin, which was mostly present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, B and C). This indicates that p120 preferentially binds to N-cadherin in these cells, and the association with p120 is essential for cadherin retention at adherens junctions. Y658F VE-cadherin, in contrast, was able to localize at cell-cell contacts with the concomitant colocalization with p120 (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Y658F mutant, but not Y658E, is associated with p120-catenin. A–D: RFPECs expressing VEC-WT, Y658E, or Y658F mutants were fixed, and the expression patterns of GFP-tagged VE-cadherin and p120-catenin were determined by immunofluorescence. Cells were stained for VE-cadherin (red) and p120-catenin (blue). Note that Y658F mutants clearly colocalized with p120-catenin (arrows in D). Scale bars = 10 μm. E and F: RFPECs expressing VEC-WT, Y658E, or Y658F mutants were lysed, and p120-catenin (E) or VE-cadherin (F) was immunoprecipitated (IP). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. G: human umbilical vein endothelial cells expressing VE-cadherin-GFP (WT, Y658E, or Y658F) were lysed, and VE-cadherin-GFP was immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP antibody. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Note that Y658E mutation disrupted VE-cadherin-p120-catenin association.

In line with this observation, coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that in cells expressing either WT or Y658E VE-cadherin, p120 associated with N-cadherin with no obvious interaction with VE-cadherin. On the other hand, Y658F VE-cadherin is able to bind p120, suggesting that the dephosphorylation of Y658 is required for this interaction (Fig. 4, E and F).

These results were also confirmed in HUVECs overexpressing VE-cadherin mutants. When immunoprecipitated with an anti-GFP antibody, p120 preferentially associated with nonphosphorylated form of VE-cadherin. Furthermore, WT VE-cadherin, which is not degraded in HUVECs and localized at cell-cell contacts, can also bind to p120 as expected (Fig. 4G).

Together, these data indicate that N- or VE-cadherin localization at adherens junction requires an association with p120 and that in the case of VE-cadherin, this binding is regulated by Y658 phosphorylation.

Regulation of cell migration by VE-cadherin phosphorylation.

We hypothesized that cell motility is affected by the strength of cell-cell adhesiveness controlled by the interaction of p120 and VE-cadherin. To test this possibility and to evaluate the relationship between VE-cadherin Y658 phosphorylation and cell motility, we next examined in vitro cell migration in normal growth medium using a wound healing assay. Cell front migration was significantly delayed in cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin compared with control cells (RFPECs) (Fig. 5, A and B). In contrast, Y658E VE-cadherin-expressing cells retained migratory capacity compared with WT RFPECs in which VE-cadherin junctions are absent. In line with this observation, we found that, at the migrating front, most cells expressing Y658E VE-cadherin formed lamellipodia, whereas cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin were incapable of forming membrane protrusions (Fig. 5, C and D, supplemental movie 1 and 2). Interestingly, while Y658E cells formed intricate radial actin bundles, Y658F cells showed circumferential actin cables that are observed when cells form mature junctions (Fig. 5C) (8). Moreover, when compared with cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin, Y658E cells had more internalized VE-cadherin, suggesting that active VE-cadherin endocytosis took place in these cells in the absence of p120 binding (Fig. 5C, and supplemental movie 1 and 2). These findings indicate that cell migration is impaired when VE-cadherin is associated with p120 and that uncoupling of p120 and subsequent VE-cadherin internalization is required for the induction of actin reorganization and acquisition of the motile phenotype.

Fig. 5.

Y658F mutation impairs cell migration, whereas Y658E mutation is sufficient to promote the migratory response. Cells in 6-well plates were cultured confluent. A scratch was made using a 200-μl tip, and the cells were allowed to migrate for 16 h. A: representative pictures at 0 and 16 h. B: relative gap closure was measured using ImageJ software. Data are means ± SD for n = 8. *P < 0.01 by t-test compared with RFPECs or Y658E. C and D: Y658F impaired lamellipodia formation. C: RFPECs expressing Y658E or Y658F at the migrating front were stained with actin (red) using Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin. Scale Bars = 10 μm. D: the number of cells with lamellipodia at the wound edge was counted. Data are means ± SD for n = 8 *P < 0.01 by t-test.

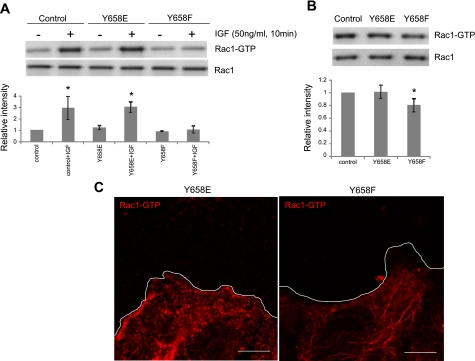

Rac1 activation is reduced in Y658F cells.

Since our observation indicates that VE-cadherin Y658 phosphorylation affects EC migration and lamellipodia formation, we next tested the possibility that Rac1 activity is altered in cells expressing VE-cadherin Y658 mutants. Rac1 pull-down assays showed that Rac1 activity was increased in response to IGF stimulation in control cells or Y658E VE-cadherin-expressing cells; however, no activation was observed in cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin (Fig. 6A). Rac1 activity of migrating ECs in normal growth medium was also decreased in Y658F VE-cadherin-expressing cells (Fig. 6B). Spatial control of Rac1 activation is important for directional cell movement; therefore, we next examined whether Rac1 activity is decreased in membrane ruffles of VE-cadherin Y658F cells at the migration front. Immunostaining detecting GTP-bound Rac1 demonstrated that active Rac1 was not localized at lamellipodia in cells carrying the VE-cadherin Y658F mutant (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that VE-cadherin Y658 phosphorylation not only regulates cellular Rac1 activity but also controls the localization of active Rac1. They also imply that VE-cadherin is part of the signaling machinery that leads to the activation of Rac1 at the membrane ruffles and promotes cell migration.

Fig. 6.

Rac1 activity is impaired in Y658F cells. A, top: RFPECs were cultured in 0.5% FBS-DMEM for 24 h before Rac1 activity assay. Cells were treated with 50 ng/ml IGF for 10 min before lysis. Rac1 was activated by IGF in control cells, and Y658E VE-cadherin-expressing cells, but not in Y658F cells. A, bottom: densitometric analysis of immunoblots. Data are means ± SD for n = 4. *P < 0.05 by t-test. B, top: RFPECs cultured in 10% FBS-DMEM were subjected to Rac1 activity assay when they reached at 50% confluency. Cells expressing Y658F VE-cadherin showed reduced Rac1 activity compared with control cells or Y658E cells. (RFPECs transfected with an empty vector were used as a control.) B, bottom: densitometric analysis of immunoblots. Data are means ± SD for n = 4. *P < 0.05 by t-test. C: cells at the migrating front were stained with the antibody against GTP-bound Rac1 (red). Note that active Rac1 did not localize at the migrating front in Y658F cells. White line indicates the cell edge at the leading front. Scale Bars = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that 1) VE-cadherin competes for junctional localization with N-cadherin, and this regulation involves phosphorylation of VE-cadherin Y658; 2) VE-cadherin localization at EC junctions is dependent on dephosphorylation of Y658, which regulates an association with p120 and stabilization of the VE-cadherin complex at cell-cell junctions; 3) EC motility and barrier function are reciprocally regulated by dynamic remodeling of VE-cadherin junctions, which is in turn controlled by the phosphorylation of Y658; and 4) Y658 phosphorylation of VE-cadherin leads to Rac1 activation and localization of activated Rac1 at the leading edge of migrating cells.

In the vasculature, the regulation of VE-cadherin endocytosis is critical for controlling endothelial permeability and barrier function (12). Src activation induced by VEGF appears to be a key event in triggering VE-cadherin internalization and adherens junction disassembly through the phosphorylation of VE-cadherin (15, 31, 40). This process is considered to be important for the establishment of angiogenic “activated” ECs. Endothelial junctions are highly dynamic structures that actively assemble and disassemble even in the quiescent monolayer, suggesting that the balance of net VE-cadherin dynamics determines the EC behavior. Our results indicate that EC migration requires a weakening of EC-EC adhesiveness that is largely regulated by VE-cadherin homophilic interactions.

In the cytoplasmic tail of VE-cadherin, at least five tyrosine (Y645, Y658, Y685, Y731, and Y733) and one serine (S665) residues are reported to be potentially phosphorylated in vitro and involved in the regulation of permeability and leukocyte transmigration (5, 16, 31, 37, 40). However, the role and biological relevance of each VE-cadherin phosphorylation event is not firmly established at this point. Direct phosphorylation of Y658 and Y731 sites by Src disrupts p120- and β-catenin binding, respectively, and increases monolayer permeability (31). VE-cadherin Y658 (equivalent to F769 in mouse E-cadherin) is part of the core interface between the COOH-terminal anchor region of the juxtamembrane domain of cadherin and the NH2-terminus of p120 (20). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the phosphorylation of this site controls p120 binding to VE-cadherin, thus regulating VE-cadherin internalization and stability. Indeed, our results show that Y658E VE-cadherin, which cannot be maintained at cell-cell contacts because of a lack of p120 binding, destabilizes cell-cell junctions, leading to a disruption of the endothelial monolayer integrity in RFPECs. We speculate that Y658E VE-cadherin can be targeted to the membrane but is then rapidly excluded from adherens junctions because of the inability to associate with p120 efficiently and to retain stably as a complex. For this reason, the junctional localization of N-cadherin/p120 is not as sharp in cells expressing Y658E VE-cadherin (Figs. 1C and Fig. 4C, and supplemental Fig. 1C). As a result, the contact integrity measured by ECIS is decreased and not significantly affected by N-cadherin depletion (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, VE-cadherin lacks the endocytic LL motif that is present in the juxtamembrane domain of E-cadherin and involved in adopter protein binding and subsequent endocytosis. This may imply the existence of alternative endocytic regulation mediated by a phosphorylation-based mechanism for VE-cadherin.

The critical role of p120 in cadherin stability at adherens junction and the cadherins' adhesive function is well established. In epithelial junctions, direct p120-E-cadherin interaction is crucial for the maintenance of epithelial morphology, and the cadherin adhesion system is disrupted as a direct consequence of p120 insufficiency or uncoupling (19). Furthermore, p120 acts at the cell surface to control cadherin turnover, thereby regulating cadherin levels. p120 knockdown results in the elimination of multiple cadherins including VE-cadherin in ECs and a loss of cell-cell adhesion (9). VE-cadherin endocytosis is inhibited by p120 via a mechanism that requires direct interactions between p120 and the VE-cadherin juxtamembrane domain, and VE-cadherin-p120 complex dissociates upon internalization (45). In contrast, β-catenin remains associated with VE-cadherin after internalization (43, 44). Although the role of Src in VEGF-induced permeability change has been well established, the subsequent events leading to junction disruption are still controversial. Our findings that the phosphorylation of VE-cadherin Y658 is required for p120 dissociation and permeability increase are consistent with those of Potter et al. (31) but not with recent study by Adam et al. (3), who described that Src-induced Y658 phosphorylation is not sufficient for p120 dissociation and the loss of barrier function of endothelial monolayers. This can be attributed to the difference of cell types used in different studies, but we observed similar effect using HUVECs, suggesting our finding is not a specific event that occurs in the artificial system reconstituted in non-ECs. A plausible explanation would be that the phosphorylation of the Y658 VE-cadherin is a first step and that the second hit that eventually changes the protein conformation and p120 dissociation are also required to lead functional alterations.

Interestingly, while tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin is thought to account for the action of many agents capable of increasing permeability including growth factors and inflammatory mediators, to date the functional relevance of these phosphorylation events to new vessel formation is not well established. It has been recently shown that VE-cadherin is implicated in the formation of vascular connection and the inhibition of sprouting activity in the developing vasculature in zebrafish (2, 26). Furthermore, the downregulation of VE-cadherin in EC-derived tumor increases the incidence of hemorrhage and exaggerated tumor growth, suggesting an inhibitory role of VE-cadherin in tumor progression (47). Our study demonstrates that the maintenance of dephosphorylated status of VE-cadherin Y658 is important for tight barrier function and reduced motility of ECs. While VEGF promotes VE-cadherin internalization by phosphorylating VE-cadherin, the constitutive action of VEGF is, in the long run, potentially harmful for vessels to keep homeostasis. This implies the existence of a regulatory mechanism that maintains vessel integrity possibly through activating a protein tyrosine phosphatase toward Y658 of VE-cadherin or inhibiting Src activity. In the quiescent vasculature, this appears to be achieved by physiological fibroblast growth factor signaling in the endothelium, which plays a key role in the maintenance of vascular integrity (28).

The precise role of N-cadherin in the vasculature remains unknown despite its relatively abundant expression in ECs. Although it has been thought that N-cadherin is diffusely distributed on the cell surface while VE-cadherin assumes junctional localization (29), a recent study demonstrated that N-cadherin can also exist at adherens junctions in ECs and controls VE-cadherin expression (23). Moreover, although in primary ECs, VE-cadherin is responsible for the junctional exclusion of N-cadherin, in the absence of VE-cadherin, N-cadherin localizes to cell-cell contacts (17). Hence, these studies challenge the idea of a less significant involvement of N-cadherin in homophilic EC interaction. We show in this study that N-cadherin can form cell-cell contacts and contribute to the maintenance of permeability in RFPECs. In these cells, the expression of VE-cadherin is downregulated and N-cadherin takes over junctional localization, resembling transformed cells that had undergone ephithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). In the EMT process, the loss of E-cadherin is associated with the upregulation of mesenchymal cadherin such as N-cadherin (cadherin switch), whereby epithelial cancer cells acquire the ability of anchorage-independent growth, leading to disease progression and tumor metastasis. In RFPECs, the expression of WT VE-cadherin leads to its degradation in the presence of N-cadherin; nevertheless, N-cadherin depletion by siRNA restores the junctional localization of WT VE-cadherin. Intriguingly, Y658F VE-cadherin can bind to p120 and distribute at cell-cell contacts even in the presence of N-cadherin with an enhancement of barrier function. This suggests that a physical interaction with p120 may prevent VE-cadherin from N-cadherin-driven exclusion from cell-cell contacts. In fact, the phosphomimetic mutation of Y658 displays cytoplasmic distribution and is not affected by N-cadherin depletion, probably due to the inherent inability to bind to p120. We speculate that in normal ECs, p120 preferentially binds to VE-cadherin, not to N-cadherin, thereby maintaining quiescence; however, in the angiogenic endothelium where an active proliferation and migration take place, p120 may switch the partner to N-cadherin upon Y658 phosphorylation and disruption of VE-cadherin-based junctions. Several cadherins including N-, E-, and VE-cadherin are known to be cleaved by a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) and γ-secretase by which a cytoplasmic fragment is released and cell surface cadherin is downregulated (13, 24, 25, 32, 33). Since we have observed in this study a degradation of WT VE-cadherin when transfected in RFPECs, it is of particular interest to investigate the physiological relevance and the proteolytic machinery involved in this process.

In the present study, the Y658F mutation of VE-cadherin led to a marked decrease of lamellipodia formation at the migrating front, accompanied with local impairment of Rac1 activation. In contrast with cells expressing Y658E VE-cadherin in which p120 predominantly binds to N-cadherin, Y658F VE-cadherin binds to p120 efficiently, raising a possibility that VE-cadherin competes for p120 against N-cadherin. A similar p120 competition between epithelial and mesenchymal cadherins has been reported to occur in EMT and significantly influences tumor cell migration and invasiveness. Whereas p120-E-cadherin interaction suppresses Rac1, p120-N-cadherin (or cadherin-11) binding not only promotes cell motility by activating Rac1 but also increases cell proliferation through MAPK activation (35, 46). It is possible that this mechanism also applies to ECs where p120 association with either VE- or N-cadherin may determine cell behaviors. Interestingly, p120, originally identified as a Src substrate, is differentially phosphorylated by Src and Fyn, thereby controlling RhoA affinity to p120 and potentially RhoA activity (7).

It has been well recognized that cadherins can modulate Rho GTPase activities at cell-cell contacts, thereby controlling junction formation, stability, and adhesiveness (22, 42). Rac1 is implicated in not only junction assembly and maintenance but also barrier breakdown and cell migration in ECs (36). Since in our study Rac1 activity was measured in migrating ECs at low confluency, it is not appropriate to evaluate the effect of VE-cadherin phosphorylation in Rac1 activity required for barrier maintenance. It has been known that Rac1 affects VE-cadherin function and thus modifying junction properties. However, our data demonstrate that VE-cadherin, by altering the phosphorylation status of Y658, is capable of modulating downstream Rac1 activity at the leading edge, distant from cell junctions. This implies that there is a signaling network that converts spatial information sensed by adhesion receptors to specialized cell behaviors such as directional migration. Importantly, our data indicate that VE-cadherin is part of this machinery, and phosphorylation of Y658 is the key to switching of EC phenotype from adhesive to motile.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-053793 (to M. Simons); American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 10SDG4170137 (to M. Murakami); and intramural funding from Yale University School of Medicine (to M. Murakami).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Amy Hall for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abe K, Takeichi M. EPLIN mediates linkage of the cadherin catenin complex to F-actin and stabilizes the circumferential actin belt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13–19, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abraham S, Yeo M, Montero-Balaguer M, Paterson H, Dejana E, Marshall CJ, Mavria G. VE-Cadherin-mediated cell-cell interaction suppresses sprouting via signaling to MLC2 phosphorylation. Curr Biol 19: 668–674, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adam AP, Sharenko AL, Pumiglia K, Vincent PA. Src-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin is not sufficient to decrease barrier function of endothelial monolayers. J Biol Chem 285: 7045–7055, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anastasiadis PZ. p120-ctn: a nexus for contextual signaling via Rho GTPases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773: 34–46, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumeister U, Funke R, Ebnet K, Vorschmitt H, Koch S, Vestweber D. Association of Csk to VE-cadherin and inhibition of cell proliferation. EMBO J 24: 1686–1695, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carmeliet P, Lampugnani MG, Moons L, Breviario F, Compernolle V, Bono F, Balconi G, Spagnuolo R, Oostuyse B, Dewerchin M, Zanetti A, Angellilo A, Mattot V, Nuyens D, Lutgens E, Clotman F, de Ruiter MC, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R, Lupu F, Herbert JM, Collen D, Dejana E. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell 98: 147–157, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castano J, Solanas G, Casagolda D, Raurell I, Villagrasa P, Bustelo XR, Garcia de Herreros A, Dunach M. Specific phosphorylation of p120-catenin regulatory domain differently modulates its binding to RhoA. Mol Cell Biol 27: 1745–1757, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cavey M, Lecuit T. Molecular bases of cell-cell junctions stability and dynamics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a002998, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis MA, Ireton RC, Reynolds AB. A core function for p120-catenin in cadherin turnover. J Cell Biol 163: 525–534, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Agostini AI, Watkins SC, Slayter HS, Youssoufian H, Rosenberg RD. Localization of anticoagulantly active heparan sulfate proteoglycans in vascular endothelium: antithrombin binding on cultured endothelial cells and perfused rat aorta. J Cell Biol 111: 1293–1304, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dejana E. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: happy together. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 261–270, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delva E, Kowalczyk AP. Regulation of cadherin trafficking. Traffic 10: 259–267, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donners MM, Wolfs IM, Olieslagers S, Mohammadi-Motahhari Z, Tchaikovski V, Heeneman S, van Buul JD, Caolo V, Molin DG, Post MJ, Waltenberger J. A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 is a novel mediator of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell function in angiogenesis and is associated with atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 2188–2195, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elfenbein A, Rhodes JM, Meller J, Schwartz MA, Matsuda M, Simons M. Suppression of RhoG activity is mediated by a syndecan 4-synectin-RhoGDI1 complex and is reversed by PKCalpha in a Rac1 activation pathway. J Cell Biol 186: 75–83, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esser S, Lampugnani MG, Corada M, Dejana E, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces VE-cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci 111: 1853–1865, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gavard J, Gutkind JS. VEGF controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the beta-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Nat Cell Biol 8: 1223–1234, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gentil-dit-Maurin A, Oun S, Almagro S, Bouillot S, Courcon M, Linnepe R, Vestweber D, Huber P, Tillet E. Unraveling the distinct distributions of VE- and N-cadherins in endothelial cells: a key role for p120-catenin. Exp Cell Res 316: 2587–2599, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ha CH, Bennett AM, Jin ZG. A novel role of vascular endothelial cadherin in modulating c-Src activation and downstream signaling of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem 283: 7261–7270, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ireton RC, Davis MA, van Hengel J, Mariner DJ, Barnes K, Thoreson MA, Anastasiadis PZ, Matrisian L, Bundy LM, Sealy L, Gilbert B, van Roy F, Reynolds AB. A novel role for p120 catenin in E-cadherin function. J Cell Biol 159: 465–476, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishiyama N, Lee SH, Liu S, Li GY, Smith MJ, Reichardt LF, Ikura M. Dynamic and static interactions between p120 catenin and E-cadherin regulate the stability of cell-cell adhesion. Cell 141: 117–128, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lampugnani MG, Orsenigo F, Gagliani MC, Tacchetti C, Dejana E. Vascular endothelial cadherin controls VEGFR-2 internalization and signaling from intracellular compartments. J Cell Biol 174: 593–604, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lampugnani MG, Zanetti A, Breviario F, Balconi G, Orsenigo F, Corada M, Spagnuolo R, Betson M, Braga V, Dejana E. VE-cadherin regulates endothelial actin activating Rac and increasing membrane association of Tiam. Mol Biol Cell 13: 1175–1189, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo Y, Radice GL. N-cadherin acts upstream of VE-cadherin in controlling vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 169: 29–34, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marambaud P, Wen PH, Dutt A, Shioi J, Takashima A, Siman R, Robakis NK. A CBP binding transcriptional repressor produced by the PS1/epsilon-cleavage of N-cadherin is inhibited by PS1 FAD mutations. Cell 114: 635–645, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maretzky T, Reiss K, Ludwig A, Buchholz J, Scholz F, Proksch E, de Strooper B, Hartmann D, Saftig P. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9182–9187, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Montero-Balaguer M, Swirsding K, Orsenigo F, Cotelli F, Mione M, Dejana E. Stable vascular connections and remodeling require full expression of VE-cadherin in zebrafish embryos. PloS One 4: e5772, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murakami M, Horowitz A, Tang S, Ware JA, Simons M. Protein kinase C (PKC) delta regulates PKCalpha activity in a Syndecan-4-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 277: 20367–20371, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Zhuang ZW, Moodie KL, Carmeliet P, Stan RV, Simons M. The FGF system has a key role in regulating vascular integrity. J Clin Invest 118: 3355–3366, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Navarro P, Ruco L, Dejana E. Differential localization of VE- and N-cadherins in human endothelial cells: VE-cadherin competes with N-cadherin for junctional localization. J Cell Biol 140: 1475–1484, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oas RG, Xiao K, Summers S, Wittich KB, Chiasson CM, Martin WD, Grossniklaus HE, Vincent PA, Reynolds AB, Kowalczyk AP. p120-Catenin is required for mouse vascular development. Circ Res 106: 941–951, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Potter MD, Barbero S, Cheresh DA. Tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin prevents binding of p120- and beta-catenin and maintains the cellular mesenchymal state. J Biol Chem 280: 31906–31912, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reiss K, Maretzky T, Ludwig A, Tousseyn T, de Strooper B, Hartmann D, Saftig P. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signalling. EMBO J 24: 742–752, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schulz B, Pruessmeyer J, Maretzky T, Ludwig A, Blobel CP, Saftig P, Reiss K. ADAM10 regulates endothelial permeability and T-cell transmigration by proteolysis of vascular endothelial cadherin. Circ Res 102: 1192–1201, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shaw SK, Bamba PS, Perkins BN, Luscinskas FW. Real-time imaging of vascular endothelial-cadherin during leukocyte transmigration across endothelium. J Immunol 167: 2323–2330, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soto E, Yanagisawa M, Marlow LA, Copland JA, Perez EA, Anastasiadis PZ. p120 catenin induces opposing effects on tumor cell growth depending on E-cadherin expression. J Cell Biol 183: 737–749, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spindler V, Schlegel N, Waschke J. Role of GTPases in control of microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res 87: 243–253, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turowski P, Martinelli R, Crawford R, Wateridge D, Papageorgiou AP, Lampugnani MG, Gamp AC, Vestweber D, Adamson P, Dejana E, Greenwood J. Phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cadherin controls lymphocyte emigration. J Cell Sci 121: 29–37, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature 437: 426–431, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vestweber D, Winderlich M, Cagna G, Nottebaum AF. Cell adhesion dynamics at endothelial junctions: VE-cadherin as a major player. Trends Cell Biol 19: 8–15, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallez Y, Cand F, Cruzalegui F, Wernstedt C, Souchelnytskyi S, Vilgrain I, Huber P. Src kinase phosphorylates vascular endothelial-cadherin in response to vascular endothelial growth factor: identification of tyrosine 685 as the unique target site. Oncogene 26: 1067–1077, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Watanabe T, Sato K, Kaibuchi K. Cadherin-mediated intercellular adhesion and signaling cascades involving small GTPases. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 1: a003020, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wildenberg GA, Dohn MR, Carnahan RH, Davis MA, Lobdell NA, Settleman J, Reynolds AB. p120-Catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell 127: 1027–1039, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wright TJ, Leach L, Shaw PE, Jones P. Dynamics of vascular endothelial-cadherin and beta-catenin localization by vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis in human umbilical vein cells. Exp Cell Res 80: 159–168, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xiao K, Allison DF, Buckley KM, Kottke MD, Vincent PA, Faundez V, Kowalczyk AP. Cellular levels of p120 catenin function as a set point for cadherin expression levels in microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 163: 535–545, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiao K, Garner J, Buckley KM, Vincent PA, Chiasson CM, Dejana E, Faundez V, Kowalczyk AP. p120-Catenin regulates clathrin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Mol Biol Cell 16: 5141–5151, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yanagisawa M, Anastasiadis PZ. p120 catenin is essential for mesenchymal cadherin-mediated regulation of cell motility and invasiveness. J Cell Biol 174: 1087–1096, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zanetta L, Corada M, Grazia Lampugnani M, Zanetti A, Breviario F, Moons L, Carmeliet P, Pepper MS, Dejana E. Downregulation of vascular endothelial-cadherin expression is associated with an increase in vascular tumor growth and hemorrhagic complications. Thromb Haemost 93: 1041–1046, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.