Abstract

We have developed an optical method for the evaluation of the oxygen consumption (V̇o2) in microscopic volumes of spinotrapezius muscle. Using phosphorescence quenching microscopy (PQM) for the measurement of interstitial Po2, together with rapid pneumatic compression of the organ, we recorded the oxygen disappearance curve (ODC) in the muscle of the anesthetized rats. A 0.6-mm diameter area in the tissue, preloaded with the phosphorescent oxygen probe, was excited once a second by a 532-nm Q-switched laser with pulse duration of 15 ns. Each of the evoked phosphorescence decays was analyzed to obtain a sequence of Po2 values that constituted the ODC. Following flow arrest and tissue compression, the interstitial Po2 decreased rapidly and the initial slope of the ODC was used to calculate the V̇o2. Special analysis of instrumental factors affecting the ODC was performed, and the resulting model was used for evaluation of V̇o2. The calculation was based on the observation of only a small amount of residual blood in the tissue after compression. The contribution of oxygen photoconsumption by PQM and oxygen inflow from external sources was evaluated in specially designed tests. The average oxygen consumption of the rat spinotrapezius muscle was V̇o2 = 123.4 ± 13.4 (SE) nl O2/cm3·s (N = 38, within 6 muscles) at a baseline interstitial Po2 of 50.8 ± 2.9 mmHg. This technique has opened the opportunity for monitoring respiration rates in microscopic volumes of functioning skeletal muscle.

Keywords: respiratory rate, interstitial Po2, oxygen disappearance curve

the local oxygen consumption (V̇o2) in a tissue is an important indicator of its metabolic activity under physiological and pathological conditions. An indirect method to determine V̇o2 of perfused tissues based on Fick's principle combines data on regional blood flow and arterio-venous oxygen content difference (5, 19, 28, 37). The mass-specific V̇o2 in a large volume of tissue or a whole organ is calculated as the product of these two values. In this technique the determination of local blood flow and the reference volume of tissue represent significant methodological problems. Another technique is based on the one-dimensional model of the oxygen consumption and diffusion and applicable only to avascular tissue regions next to microvessels, as in the mesentery. V̇o2 can be calculated by fitting the radial Po2 profile in a thin tissue with the quadratic solution of the one-dimensional model of oxygen diffusion and consumption (49). However, this method can be applied only to a few experimental situations in the vicinity of spatially isolated microvessels.

A more direct method of local tissue V̇o2 measurements in situ proposed by Kunze and Lubbers (32) was based on an analysis of the oxygen disappearance curve (ODC) in the tissue region after instant arrest of its perfusion with a hemoglobin-free solution. Under these conditions, V̇o2 was calculated as the product of the initial rate of the Po2 decrease and oxygen solubility in the tissue. The local ODC in this method was recorded using a polarographic cathode 0.2 mm in diameter. A combination of the polarographic ODC recording with instant circulatory arrest was successfully applied to V̇o2 measurements in the heart (32), brain (15, 34, 40), and carotid body (1, 55). Independence of the ODC from hemoglobin-bound oxygen was achieved by perfusion of the tissue with hemoglobin free solutions (15, 32) or by keeping the tissue Po2 well above 100 mmHg (34). Intensive theoretical studies of the factors involved in the formation of the ODC were undertaken for situations independent and dependent on oxygen bound to hemoglobin (1, 10, 40, 42).

The further development of ODC-based V̇o2 measurements was complicated by substantial limitations of the microelectrode technique. The most accurate Po2 measurements with a microelectrode require one with minimal oxygen consumption and low sensitivity to stirring (15, 32, 34, 55, 56). However, the use of a microelectrode is incompatible with isolation of tissue from room air with a barrier film material. Inevitably, the superficial layers of tissue are contaminated by oxygen transmitted through the superfusion solution.

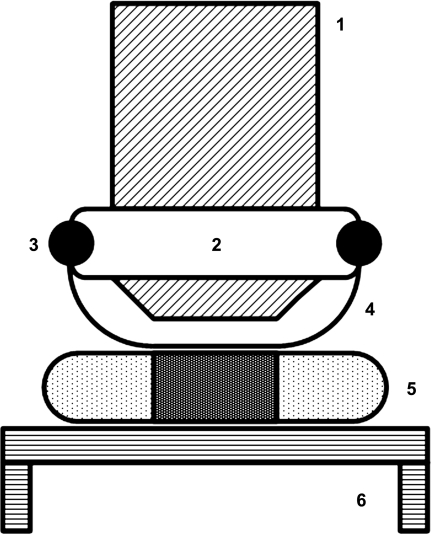

Progress in optical techniques for oxygen measurements (52, 53, 58) opened the opportunity for noninvasive registration of the ODC in a tissue, which is well isolated from atmospheric oxygen with a transparent gas barrier film or glass. Technical advances in the phosphorescence quenching method to oxygen measurements in microscopic volumes (46, 50, 51, 59) provided the necessary spatial and temporal resolution for measurements of Po2 using phosphorescence quenching microscopy (PQM). In PQM the signal can be localized on the basis of the illuminated area, volume of probe distribution, and depth of penetration of the excitation light. In thin planar muscles used for bio-microscopic studies of the microcirculation, the size of the excitation light spot can be adjusted to select a volume of tissue for measuring the mean V̇o2 using analysis of the ODC. The phosphorescent oxygen probe loaded into the interstitial space (47, 57) provides measurements of Po2 values on the surface of muscle fibers during the perfusion and after the flow arrest in microvessels. However, interpretation of the ODC obtained with PQM in terms of V̇o2 is complicated by the presence of hemoglobin in the red blood cells (RBCs) of the stopped blood. Reduction of the hemoglobin contribution to the ODC with hyperoxia and saline flush techniques (15, 32, 34) are too invasive and disturbing for microcirculatory experiments. We have developed the PQM technique for measurements of tissue V̇o2 based on analysis of the ODC caused by the momentary compression of a tissue region with a pneumatic tool, invented in the late nineteenth century by Roy and Brown (44). The rapid onset of pressure in the inflatable bag causes an immediate arrest of the circulation and extrusion of blood from most of the microvessels in the tissue under the microscope objective, which makes the recorded ODC practically independent from any contribution of hemoglobin.

In the phosphorescence quenching method absorption of the excitation light pulse by molecules of the phosphorescent probe generates excited triplet states. Quenching of these triplet states by oxygen gives rise to singlet oxygen that irreversibly reacts with nearby organic substrates (18, 29). Thus a fraction of the dissolved oxygen in the illuminated tissue disk disappears during every excitation/emission cycle in a process called photoconsumption of oxygen. Continuous Po2 measurements in tissue require repeating multiple excitation light pulses. The Po2 drop caused by a series of flashes in the illuminated volume of fluid containing the phosphorescent probe accumulates, resulting in an underestimation of the measured Po2 (21, 41, 53). Photoactivated oxygen depletion by the method (autoconsumption) at a low flash rate is usually compensated by convective oxygen delivery in a well perfused tissue. However, this oxygen depletion poses a serious problem in the case of a limited external oxygen supply and high flash rate. This effect is more pronounced in avascular tissue regions (e.g., mesentery) or in a tissue without blood circulation. Compression of tissue with the application of external pressure stops the perfusion and removes blood from the excitation volume, so the autoconsumption adds to the apparent tissue Po2 drop after flow arrest. This instrumental contribution must be accounted for to obtain the correct interpretation of the ODC. After correction for autoconsumption by PQM, an opportunity is opened to use brief tissue compression to measure the respiration rate of a tissue in situ.

METHODS

Principle of in situ measurement of V̇o2.

The proposed technique is applicable to oxygen consumption measurements in thin planar muscles used in microcirculatory studies: spinotrapezius, cremaster, tenuissimus, etc. A muscle prepared for intravital microscopy is spread over a thermostabilized transparent pedestal of the animal stage of the microscope. The interstitial space of the tissue is then loaded with a phosphorescent probe and isolated from the air with a transparent gas barrier film. For oxygen measurements, epi-illumination with a brief light pulse is used to excite the probe inside the disk formed by the intersection of the tissue layer with the circular (for example) light beam. The interstitial space containing the phosphorescent probe inside the illuminated tissue disk is referred to as an excitation volume or reference volume. Continuous measurement requires illumination with a train of N excitation light pulses at a flash rate F. In this analysis, we will use flash number, n, as the independent variable instead of time. The first flash after the onset of tissue compression is denoted n = 1, whereas n = 0 denotes the steady-state tissue parameters before compression. The actual time points of ODC registration, t = n/F, will be restored at the end of the ODC analysis.

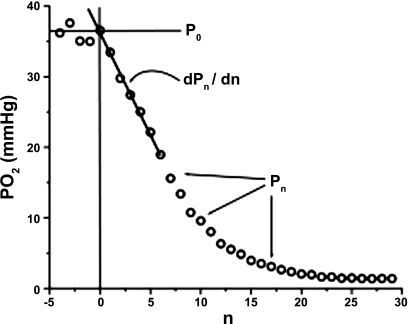

Consider that the interstitial Po2 inside the excitation volume under conditions of normal blood flow is Po2 = P0 (typical ODC presented in the Fig. 1). The measuring procedure may distort the normal oxygen level when high oxygen consumption by a single excitation flash is combined with a high flash rate. The required autoconsumption rate can be set in experiments with nonrespiring tissue (see below) by adjusting the concentration of phosphorescent probe and the flash energy density. The allowable limits of the excitation flash rate in a perfused tissue can be estimated by using half of the intercapillary distance as a characteristic dimension for the recovery of the Po2 disturbance caused by the excitation light pulses. The linear density of perfused capillaries in the spinotrapezius muscle is 31 mm−1 (13), so that the spatial period of capillaries is 32 μm. Accounting for the capillary diameter of 5.5 μm (13), the distance in tissue from capillary wall to the midpoint between capillaries is x = 13.5 μm. Oxygen diffusivity in skeletal muscle is DO2 = 1.45·10−5 cm2/s (35). The time required for 90% restoration (14) of the disturbed Po2 at the midpoint can be estimated as T90 = 0.54 x2/DO2 = 0.067 s, corresponding to a maximal flash rate of 15 Hz. This estimation indicates that Po2 measurements in the normally perfused spinotrapezius muscle at flash rates lower than 10 Hz are not affected by accumulated autoconsumption.

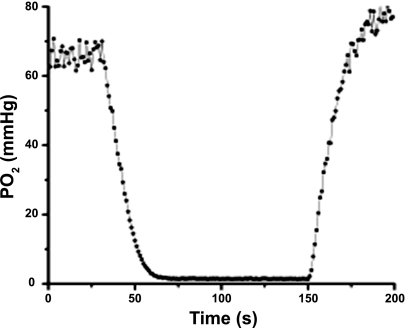

Fig. 1.

Parameters of a typical oxygen disappearance curve (ODC). P0 is mean interstitial Po2 before muscle compression, Pn is Po2 after flash n, n is flash number (n = 0 at the moment of the tissue compression), and dPn /dn determined at the beginning of the ODC is initial slope of the curve.

The rapid onset of high external pressure on a flat, thin muscle interrupts the circulation and extrudes blood from the vessels. This circumstance makes the ODC practically independent of hemoglobin. Beginning with the moment of flow arrest, Po2 values (Pn) in the sampled tissue disk are measured with a sequence of excitation flashes (n = 1…N) that form the ODC data set. The index n = 0 is used for parameter values immediately before tissue compression. In the tissue outside the illuminated area the rate of Po2 decrease is determined solely by tissue oxygen consumption dpn/dn = −Vn, where pn is the interstitial Po2 in the not illuminated tissue after the n-th excitation light pulse. The value of V0 determined at the beginning of tissue compression can be used to calculate tissue V̇o2 before the elevated pressure onset.

To obtain representative data on interstitial Po2 the illuminated area needs to cover several muscle fibers so that R should be larger than about 100 μm. Following the onset of tissue compression, autoconsumption in the illuminated tissue cannot be compensated for by oxygen inflow from capillaries. The limitations on the Po2 measurements under this condition have been analyzed previously (21). In the measurements aimed to determine the rate of oxygen disappearance, the accumulated autoconsumption of oxygen in a large excitation area is inevitable and must be accounted for.

The interstitial Po2 measured inside an illuminated tissue disk (Pn) is jointly determined by tissue V̇o2, autoconsumption, and oxygen inflow from the surrounding tissue. Oxygen inflow to the disk is proportional to a boundary Po2 difference (pn − Pn). We also assume that the O2 inflow does not affect the external Po2, since the tissue volume outside of the illuminated disk is much larger than the sampled volume inside it. Note that we do not attempt to describe the details of oxygen diffusion into the externally supplied cylinder, since this description can be found elsewhere (14). Our purpose is to account for factors affecting the measurement of oxygen consumption in the tissue with PQM. The rate of Po2 decrease inside the excitation volume is:

| (1) |

In this equation, Pn is the measured Po2 after flash number n and dPn /dn is the rate of oxygen disappearance, determined as the initial slope of the ODC by linear fitting of the Pn curve or averaging the Po2 drop for a few initial data points. The autoconsumption coefficient K depends on the excitation energy density and probe concentration (11, 21, 38, 41). If these parameters are the same in all measurements, then K remains constant. For reliable Po2 measurements it is desirable to have K<0.01 and KP0 ≪Vn. The contribution of the oxygen inflow to the interstitial Po2 within the illuminated tissue disc decreases with an increase in its radius, so the inflow coefficient Z can be made relatively small (Z<K). At the beginning of the ODC, when (pn − Pn) is small, if Z is also small, the product Z (pn − Pn), which represents the contribution of diffusive oxygen inflow for the determination of V0, can be neglected and Eq. 1 can be simplified for practical purposes to:

| (2) |

Both terms in this equation can be obtained from an analysis of the experimental ODC, and V0 can be converted to Vo2 using the factors of flash rate and oxygen solubility in the tissue (α):

| (3) |

This result corresponds to the beginning of the ODC and V̇o2 in the tissue before compression and occlusion of microvessels.

Evaluation of the coefficients K and Z can be made from the ODC obtained in a nonrespiring oxygenated tissue sample under the same conditions as Po2 measurements in vivo. In this case Vn = 0 and the tissue outside the illuminated disk is saturated with O2 to the samesteady steady PO2 level pn = P0.

Eq. 1 for a nonrespiring tissue (V0 = 0) can be written as:

| (4) |

Integration of Eq. 4 allows us to express the fitting model for an ODC recorded in nonrespiring tissue as:

| (5) |

In the presence of oxygen inflow into the disc, its average interstitial Po2 never reaches zero, but instead approaches the asymptotic Po2 value (Pa) formed by the equilibrium between the processes of autoconsumption and oxygen inflow:

| (6) |

When oxygen inflow is negligible, as in the case of a large excitation area, the Po2 finally approaches zero and Eq. 5 is transformed into:

| (7) |

The experimental ODC in nonrespiring tissue now can be fit with the proposed model and used for the estimation of the parameters K and Z. These coefficients can then be used for analysis of the experimental ODC data collected in situ in the living muscle, according to Eqs. 1–3.

Experimental animals.

All procedures were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are consistent with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the humane treatment of laboratory animals, as well as the American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were initially anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine and acepromazine mixture (72 ketamine/3 acepromazine mg/kg). The trachea was cannulated with polyethylene tubing (PE 240) to maintain a patent airway. The jugular vein was cannulated with polyethylene tubing (PE 90) for continuous intravenous infusion of alfaxalone-alfadolone (Saffan, Schering-Plough Animal Health, Welwyn Garden City, UK; ∼0.1 mg·kg−1·min−1). The anesthetic rate was adjusted as needed to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia, as evidenced by the absence of a toe pinch reflex and stable vital signs (heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and respiratory rate). Arterial pressure was measured continuously through a carotid catheter (MP-150; Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA). The same catheter was used for arterial blood sampling and blood gas analysis. Rectal temperature was maintained at ∼37°C by a blanket system (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Physiological parameters of animals are presented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Systemic parameters of the experimental animals

| Parameter | Means ± SE (6) |

|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 228.5 ± 4.0 |

| Arterial blood pressure, mmHg | 100.4 ± 4.0 |

| Arterial blood Po2, mmHg | 85.2 ± 8.7 |

| Arterial blood Pco2, mmHg | 29.7 ± 2.8 |

Values are means ± SE (number of animals).

Spinotrapezius muscle preparation.

The spinotrapezius muscle was used for measurement of interstitial Po2, and the surgical preparation was similar to the original description by Gray (26). The muscle was moistened with a physiologic salt solution throughout the surgical procedure, and bleeding was controlled with the use of a cautery unit. This method of preparation leaves the supplying nerve and vasculature intact, and microvascular function is maintained (3). The spinotrapezius muscle was placed on a thermostabilized transillumination pedestal of the microscope platform (22). The animal pad and organ pedestal temperatures were separately controlled by electronic heating units to maintain body and muscle temperatures at 37°C. The muscle tissue was covered with a gas barrier polyvinylidene chloride film (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) to prevent tissue contamination with atmospheric oxygen. To minimize the possibility of exposure of the preparation to the atmosphere a thin layer of vacuum grease was placed around the muscle to affix the plastic film to the pedestal.

Pneumatic tissue compression technique.

An objective-mounted airbag connected with a custom-built pressure controller allowed momentary application of high pressure to the tissue (Fig. 2). A pressure higher than systolic (130–140 mmHg) rapidly stops blood flow and extrudes blood from most of the vessels in the thin spinotrapezius muscle preparation (20). Pressure in the bag can be changed rapidly (<1 s) with a toggle valve to provide an opportunity to collect an ODC from the interstitial compartment and calculate V̇o2 as described above. The magnitude of the compressing pressure was adjusted using video monitoring of the flow arrest and blood extrusion from the microvessels caused by the onset of the pressure increase in the bag. A drop of lubricant was added between the airbag film and preparation barrier film to ensure ease of sliding when changing measurement sites.

Fig. 2.

Compression of the spinotrapezius muscle with the objective-mounted inflatable airbag made of transparent film. 1, objective lens; 2, rubber flange attached to objective barrel; 3, O-ring fastening the film bag onto the flange; 4, transparent nonelastic film membrane; 5, muscle, covered with gas barrier film; 6, thermostatic organ pedestal of the animal platform.

PQM.

The phosphorescence quenching instrument consists of an Axioplan-2 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) mounted together with other optical components on an optical breadboard (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ). The microscope was equipped with a video camera (KP-D20BU; Hitachi, Japan) and a custom-built photomultiplier unit. To avoid unnecessary excitation of the phosphorescent probe in the tissue, the colored glass long-pass filter OG 550 (Edmund Optics) was installed in the transillumination path used for imaging. Epi-illumination excitation was provided by a Q-switched 532-nm laser (Model LCS-DTL-112QT; Intelite, Minden, NV) that generated 15-ns light pulses at a rate of 1 Hz. The laser beam was expanded and its energy reduced to 0.5 μJ with a combination of neutral density filters and a rotary polarizer. The laser beam inside the microscope was directed by a dichroic mirror (565 DCLP; Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) through a 4X (NA = 0.45) objective lens onto the tissue, where it formed an excitation spot 600 μm in diameter (delivered energy density was 1.8 pJ/ μm2). Since the 532-nm excitation wavelength is on the shoulder of the Q-band absorption curve of the Pd-porphyrin phosphor, the excitation beam penetrated through the spinotrapezius muscle (300–500 μm). Phosphorescence emission was collected by the objective and detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT, Model R3896 with high voltage socket HC123-01; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). A barrier filter (reflecting interference cut-on 650 nm; Thermo Oriel, Stratford, CT) was located in front of the PMT to allow imaging with a video camera, which was mounted on another optical port. The PMT signal was directed to a transimpedance amplifier with a 5-μs gating time interval, blocking the excitation light pulse and fast autofluorescence artifacts. Phosphorescence decay curves (400 data points per curve) were digitized at a sampling rate of 100 kHz with a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (Model PC-MIO-16E-4; National Instruments, Austin, TX). The acquisition and analysis of phosphorescence decay curves was performed with custom software written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX). All experiments were performed in a dark room.

Oxygen probe preparation and administration.

The phosphorescent probe, palladium meso-tetra-(4-carboxyphenyl)- porphyrin (Pd-MTCPP) obtained from Oxygen Enterprises (Philadelphia, PA), was conjugated with BSA as proposed by Vanderkooi et al. (20, 53, 58). The probe solution (∼10 mg/ml in PBS) was delivered to the interstitial space via topical application to the surface of the spinotrapezius muscle for 30 min (20). This method of administration provides deep penetration of the probe into the muscle throughout the interstitial fluid and results in the absence of a phosphorescence signal arising from the intravascular and intracellular compartments.

Localization of the phosphorescent probe in the muscle.

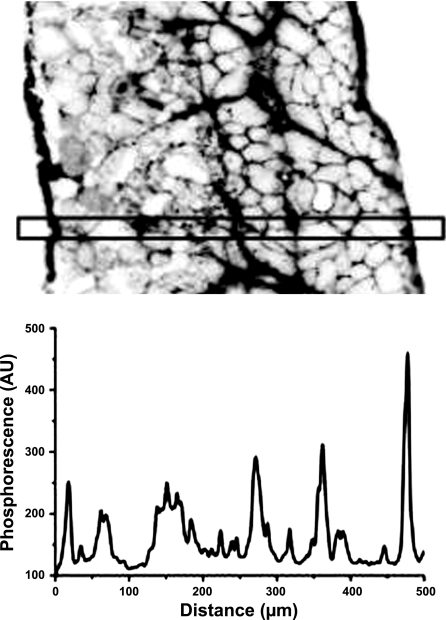

Since the Pd-MTCPP probe is bound to albumin, it was expected to remain in the interstitial space. The large molecular weight of the albumin-bound molecule would prevent it from entering cells, and the hydrostatic pressure within the blood vessels would prevent it from entering the vasculature. To determine the distribution of the phosphorescent probe after it was applied to the muscle, the spinotrapezius muscle was removed and frozen in embedding medium (Tissue-Tek II; Lab-Tek Products, Naperville, IL). Cross-section slices (10 μm thick) were mounted on microscope slides, epi-illuminated with the excitation light, and phosphorescent microscopic images were obtained. The phosphorescence image (Fig. 3) was obtained with the same Pd-MTCPP filter set, captured with a digital camera (Coolsnap cf; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), and then processed using IPLab software (v 3.61, Scanalytics; BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD).

Fig. 3.

Top: inverted image of the phosphorescence intensity in the cross section of the rat spinotrapezius muscle loaded with palladium meso-tetra-(4-carboxyphenyl)-porphyrin (Pd-MTCCP) + BSA conjugate. Bottom: corresponding profile of the phosphorescence intensity across the muscle section indicates the deep penetration and interstitial localization of the phosphorescent oxygen probe, directly administered to the muscle surface. AU, arbitrary units.

Phosphorescence decay analysis.

A nonlinear fitting procedure (Levenberg-Marquardt) for the individual phosphorescence decay curves was based on the rectangular Po2 distribution model (23):

| (8) |

where t (in μs) is the time from the beginning of the phosphorescence decay, It (in volt) is the phosphorescence decay curve, I0 (in volt) is the magnitude of the phosphorescence signal at t = 0, M (in mmHg) is the mean Po2 in the volume of detection, δ (in mmHg) is the half-width of the Po2 distribution, and B (in volt) is the baseline offset of the amplifier. The values of the constants for Pd-MTCPP are K0 = 18.3·10−4 μs−1 and Kq = 3.06·10−4 μs−1 mmHg−1.

Experimental protocol.

Circular regions of muscle of radius R = 300 μm containing no large microvessels were selected for V̇o2 measurements. The Po2 was sampled every second during 200 s of data collection (Fig. 4). During the first 30 s the interstitial Po2 at normal tissue perfusion was recorded. Pressure in the airbag was set to 130–140 mmHg for 90 s and then released for the next 80 s. It took several minutes to prepare for measurements at a new site, and measurements were repeated from 5 to 11 times in different regions of the same muscle.

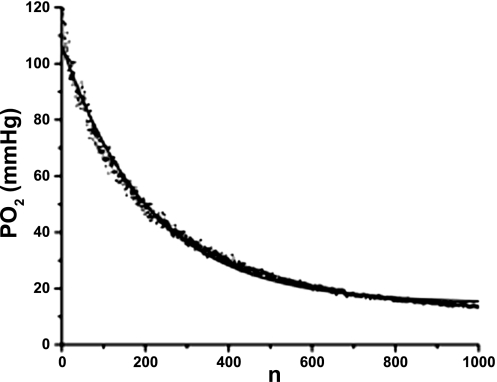

Fig. 4.

Example of the ODC recorded in nonrespiring muscle (dots) fitted with Eq. 5 (line). In this test the ODC has P0 = 117 mmHg, autoconsumption coefficient K = 41.2 10−4 (per flash, or s−1), inflow coefficient Z = 6.6 10−4 (s−1), and asymptotic Po2 (Eq. 6) Pa = 15 mmHg.

Experimental determination of K and Z.

At the end of an experiment the spinotrapezius muscle, in which the interstitium was loaded with the oxygen probe, was dissected, wrapped in Saran film, frozen and thawed for cell destruction, and left at room temperature in the dark for autolysis. A drop of kanamycin solution (1 mg/ml) was topically applied to the surface of the tissue sample. The next day (18 h later) the dead, nonrespiring tissue was exposed to air in a humid environment for 15–30 min, then wrapped again with Saran film, and left on the thermostated platform of the microscope for warming and Po2 equilibration through the tissue volume. Measurement conditions were the same as in the experiments to measure V̇o2, except the time of measurement that was extended from 200 to 1,000 s (Fig. 4). The parameters K and Z were obtained by fitting the Po2 data in a nonrespiring muscle to Eq. 5.

Calculation of the mass-specific V̇o2 in skeletal muscle.

For each experimental ODC, the mean V̇o2 before compression onset (P0) and the initial slope of the ODC were calculated. A linear region of the curve was chosen, where there is a continuous decline typically consisting of 10 points, to determine dPn/dt (in mmHg/s). In this work the flash rate was 1 Hz, so t(s) = n. Preliminary estimated coefficients K and Z were used to calculate V0 according to Eqs. 1 and 2. V̇o2 at the moment of flow arrest was then calculated according to Eq. 3, where the solubility of O2 in muscle tissue α = 0.0296 ml O2/(cm3·atm) = 39 nl O2/(cm3 mmHg) was taken from (35).

Statistics.

The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used for automatic fitting of multiple phosphorescence decays (Eq. 8) with the program written in LabView (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Statistical calculations and parameter fitting were also made using the Origin 7.0. All data presented are means ± SE (number of measurements).

RESULTS

The systemic parameters of the experimental animals are presented in Table 1.

Localization of the phosphorescent probe.

Distribution of the Pd-MTCPP across the spinotrapezius muscle is presented in Fig. 3. The thickness of the muscle measured in this section was 522 ± 6 (10) μm. With the use of the published evaluation of albumin diffusivity in rat diaphragm [9·10−8 cm2/s; (39)], the characteristic time for diffusion of the probe in the mid-plane of the muscle can be calculated as 1 h. However, phosphorescence imaging of the spinotrapezius muscle cross-sectional slices showed that the oxygen probe was distributed throughout the interstitial space of the entire muscle after only 30 min of loading on both sides. The phosphorescent image of the histological section (Fig. 3) is inverted, so that the darkest regions correspond to higher probe concentration. This image and the photometric scan in Fig. 3 demonstrate localization of the probe in the extracellular space with no evidence of its infiltration into the myocytes. This finding demonstrates the unique opportunity to measure Po2 in the interstitial fluid that contacts the surface of the muscle fibers.

Autoconsumption of oxygen and oxygen inflow.

ODCs in the nonrespiring spinotrapezius muscle were used to estimate the coefficients of autoconsumption and oxygen inflow in the excitation volume. An example of an ODC containing 1,000 consecutive Po2 measurements is presented in Fig. 4. The time course of oxygen disappearance is in good agreement with our prediction (Eqs. 4–6). The nonlinear curve fitting of the ODC using Eq. 5 demonstrates the validity of the proposed model and its basic assumptions. Parameters of the oxygen autoconsumption and oxygen inflow in the excitation tissue disc of radius R = 300 μm in the spinotrapezius muscle are shown in Table 2. Due to combining the large excitation and detection area with both low flash energy and flash rate, the effect of autoconsumption is moderate. The impact of autoconsumption on the Po2 measurements at a 1-Hz flash rate in perfused tissue can certainly be ignored (only 0.4% of P0). However, the effect of accumulated oxygen autoconsumption on the ODC may be substantial in the muscle when flow is stopped and blood is extruded from the microvessels. The coefficient of oxygen inflow, Z < K, and the effect of inflow on the initial slope of the ODC may be ignored in this situation. The coefficients K and Z estimated in the in vitro test are employed in the analysis of the ODC in living muscle according to Eqs. 1–3.

Table 2.

Average parameters of the oxygen disappearance curves obtained in nonrespiring spinotrapezius muscle

| Parameter | Means ± SE (6) |

|---|---|

| P0, mmHg | 82.2 ± 8.4 |

| Z, s−1 | (15.1 ± 3.2)·10−4 |

| K, s−1 | (40.6 ± 4.2)·10−4 |

| KP0, mmHg/s | 0.33 |

Values are means ± SE (number of measurements).

Specific oxygen consumption by the spinotrapezius muscle.

Oxygen disappearance curves were acquired in 38 regions of six spinotrapezius muscles (5–11 regions per each muscle). One of the Po2 time courses recorded before, during, and after a 2-min compression period of the spinotrapezius muscle is presented in Fig. 5. Video recordings confirmed the rapid and effective blood extrusion from the microvessels in the area of observation and measurements. We have observed that after the onset of pressure in the bag, plasma flow lasts a short time after the phase of blood extrusion. Thus erythrocytes are washed out of most of the capillaries, thereby reducing the impact of hemoglobin on the ODC. The analysis of experimental ODCs was performed with the consideration of oxygen autoconsumption according to Eqs. 1–3. The initial part of the ODCs (30–50% of P0) was found to be practically linear, indicating a constant and Po2-independent respiration rate at high Po2. This property significantly improved the accuracy of the initial slope determination by fitting the linear segment of an ODC. Results of the measurements are presented in Table 3. Interstitial Po2 in the studied regions of muscles was 50.8 mmHg, initial slope of ODC was 3.37 mmHg/s, and 6.1% of this slope was due to oxygen autoconsumption. The contribution of oxygen inflow to the initial slope was 0.15% and can be neglected. The component of the ODC due to the rate of tissue respiration was 3.16 mmHg/s, which was converted into V̇o2 = 123.4 nl O2/cm3·s or 0.74 ml O2/100 cm3 min.

Fig. 5.

A typical time course of interstitial Po2 recorded during the pneumatic compression experiment in the resting spinotrapezius muscle. High pressure in the air bag was introduced at 30 s after the beginning of the Po2 record and released at 150 s. The baseline interstitial Po2 in this example was 66 mmHg, the initial slope of the ODC was −3.41 mmHg/s, the contribution of autoconsumption was KP0 = −0.268 mmHg/s, V0 = 3.142 mmHg/s, and V̇o2 = 122.5 nl O2/cm3·s or 0.735 ml O2/100 cm3·min.

Table 3.

Parameters of oxygen consumption in the resting spinotrapezius muscle

| Parameter | Means ± SE (38) |

|---|---|

| P0, mmHg | 50.8 ± 2.9 |

| −dP/dt, mmHg/s | 3.37 ± 0.35 |

| KP0, mmHg/s | 0.206 ± 0.012 |

| V0, mmHg/s | 3.16 ± 0.34 |

| α, nl O2/cm3 mmHg | 39 |

| V̇o2, nl O2/cm3·s | 123.4 ± 13.4 |

| V̇o2, μM/s | 5.5 ± 0.6 |

| V̇o2, ml O2/100 cm3·min | 0.74 ± 0.08 |

Values are means ± SE (number of measurements). dP/dt, change in oxygen pressure (Po2) over time.

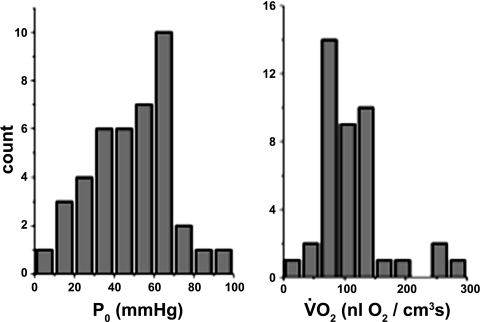

The distributions of V̇o2 and interstitial Po2 are presented in Fig. 6. No significant correlation between these two parameters for 38 data pairs was found, indicating the relative independence of the respiration rate at baseline Po2 level in resting muscle.

Fig. 6.

Histograms of the distribution of baseline interstitial Po2s (P0) and V̇o2s for 38 muscle regions. Mean values are presented in Table 3. No significant correlation between V̇o2 and baseline Po2 was found for 38 measured data pairs.

DISCUSSION

The phosphorescence quenching method applied to a continuous record of interstitial Po2 in rapidly compressed tissue provides a modern approach to the classical evaluation of in situ V̇o2 by an analysis of the ODC. This new embodiment of the ODC technique is independent of ambient oxygen, motion artifacts, and the influence of hemoglobin. Localization of the phosphorescence signal and the size of the reference volume of tissue can be controlled by setting the size of excitation and detection areas and also by the route of administration of the oxygen probe. The possibility to collect and average the signal from a much larger tissue volume than can be done using microelectrodes reduces the heterogeneity of the measurements and improves the overall quality of the signal and accuracy of the measurements. In contrast with the microelectrode technique, the size of the region of measurements can be adjusted to the requirements of the study. The optical technique of Po2 measurement is noninvasive, allowing for reliable isolation of the tissue from stray oxygen using a gas barrier film. Thus the interstitial Po2 and V̇o2 are independent from the influence of a superfusion solution. Direct loading of the probe into the interstitial space of the tissue (20, 47, 57) provides the most certain localization of the Po2 measurements in the interface between the oxygen-delivering and oxygen-consuming compartments of tissue, right on the surface of the muscle fibers.

The method of pneumatic tissue compression for the manipulation of extravascular pressure was invented in the nineteenth century by Roy and Brown (44). We modified this technique to provide a rapid and nontraumatic flow arrest and blood extrusion from microvessels in the region of tissue under study. Release of the compression pressure in the airbag immediately restores normal perfusion of the tissue. Since measurement of the V̇o2 requires only a record of the initial slope of the ODC, brief periods of compression may be periodically applied for monitoring V̇o2 during an experiment, using electro-pneumatic regulators.

The employment of a large excitation area for the Po2 measurements allowed the use of individual phosphorescence decay curves for analysis of Po2 at a relatively low level of excitation and autoconsumption. However, the contributions of autoconsumption and oxygen inflow must be accounted for in the analysis of the ODC. We developed a method to estimate empirically the coefficients of autoconsumption and oxygen inflow (Eq. 5) in a nonrespiring muscle sample, harvested after the termination of an experiment. We halted tissue respiration by freezing and thawing the sample, combined with natural tissue autolysis. In the case of application of chemical blockers to prevent tissue respiration, measures were taken to prevent probe washout from the tissue sample. The consistency between the experimental ODC in nonrespiring tissue and the fitting model (see Eq. 5 and Fig. 4) supports the validity of assumptions made in the formulation of Eq. 1. The impact of autoconsumption on baseline Po2 was small (0.2 mmHg/flash; Table 3) and cannot be accumulated in normally perfused muscle at a 1-Hz flash rate. However, in compressed tissue the contribution of autoconsumption to the ODC cannot be ignored, so we used the term KPn to correct the linear segment of the ODC used for the evaluation of V0. The inflow coefficient Z was found to be about one-third of K and can be even smaller with an increase in the radius of the excitation region or flash rate. The coefficient Z can also serve as an indicator for the contribution of hemoglobin from residual blood in the compressed tissue. Results of in vitro tests indicated that the inflow term in Eq. 1 can be omitted in calculations of V0 since it was a product of the small coefficient Z and the small Po2 difference across the border of illuminated tissue disk. After 10 flashes the Po2 difference is smaller than 2 mmHg and the value of the inflow term is about 0.003 mmHg/flash. As we reported earlier, in large excitation area instruments the inflow of oxygen is insignificant and autoconsumption of oxygen is a dominating artifact that cannot be neglected (21).

An important component of the proposed method is the unification of the pressure manipulator and the objective lens that provides video monitoring of blood discharge from the microvasculature in the region of measurement. This feature limits the scope of the method to thin organs available for bio-microscopy using transmitted light. In our experiments, there was a complete extrusion of RBCs from arterioles and venules, and single RBCs were observed in the capillaries. In this regard it is useful to estimate the worst case, maximum effect on the measurement results of blood that remained in the capillaries. For this estimation we will use data on the spinotrapezius muscle microcirculation in adult rats: capillary density, 401 mm−2 (24); internal capillary diameter, 4.28 μm (25); fraction of perfused capillaries, 75%, and capillary tube hematocrit, 22% (30); Hb content, 32 g/100 ml of RBCs; oxygen content, 1.34 ml O2/g Hb at 100% saturation (2); and oxygen solubility in muscle tissue = 0.0296 ml O2/cm3/760 torr (35). At Po2 = 50.8 mmHg rat blood contains 75% HbO2. The cross-sectional area of a capillary is 14.4 μm2, and there are 300 perfused capillaries per mm2, so that the total area occupied by perfused capillaries in the muscle cross section is 4,314 μm2/mm2. Thus perfused capillaries occupy 0.43% of total tissue volume in the muscle. The Hb content is 7.04 g/100 ml in all capillary blood and at 51 mmHg and 75% oxygen saturation the oxygen content is 7.08 ml O2/100 ml of blood or 0.03 ml O2/100 cm3 of tissue. The amount of dissolved oxygen in the muscle tissue at Po2 = 51 mmHg is 0.199 ml O2/100 cm3, so the Hb-bound oxygen comprises ∼15% of the total amount of oxygen in the muscle, in the case that all the blood remains arrested in the capillaries. When the removal of blood is not complete, this contribution may produce a systematic error in the V̇o2 measurements.

Tissue Po2 in resting skeletal muscles of small mammals has been measured by polarographic and phosphorescence quenching techniques (Table 4). Significant Po2 gradients in the microcirculation create heterogeneity in Po2 between microvessels and mitochondria, and Po2 measured in tissue is strongly dependent on localization of the oxygen signal. The catchment volume of a microelectrode may include contributions from microvessels, interstitial fluid, and parenchymal cells, with the parenchyma having the lowest Po2 and dominant higher volume. The opposite bias occurs in PQM measurements when the probe is injected into bloodstream and then extravasates, thus reporting the intravascular and interstitial Po2 signals. Reliable localization of the interstitial Po2 signal without contamination from intracellular and intravascular components is ensured only by the direct administration of the large molecular weight probe to the tissue. Our data on baseline Po2 in the interstitial space of the spinotrapezius muscle can be compared with results from workers who applied the probe directly to the interstitium (57). The interstitial Po2 values can be measured with different techniques at perivascular sites (Table 4). The tissue Po2 is significantly lower than interstitial Po2 due to the relatively larger volume of muscle fiber in comparison with the volume of other compartments.

Table 4.

Po2 in resting muscles

| Muscle | Po2, mmHg | Localization | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat gracilis | 16.7 | Tissue | Microelectrode | 54 |

| Hamster cremaster | 34.3 | Tissue, 10% O2 superfusion | Microelectrode | 31 |

| Rat spinotrapezius | 27.8 | Tissue | Microelectrode | 33 |

| Rat spinotrapezius | 17.1 | Tissue | PQM | 43 |

| Rat spinotrapezius | 36.1 | Microvascular | PQM | 3 |

| Cat sartorius | 34.2–22.8 | Tissue | Microelectrode | 9 |

| Cat sartorius | 52.1–40.1 | Periarteriolar, 2A-5A | Microelectrode | 9 |

| Mouse thigh | 40.8 | Interstitium | PQM | 57 |

| Rat cremaster | 50.7–12.5 | Interstitium 20–100 μm | PQM | 45 |

Our result of 50.8 mmHg is in good agreement with interstitial and perivascular measurements.

PQM, phosphorescence quenching microscopy.

Our measurements of V̇o2 in resting spinotrapezius muscle of rat resulted 123.4 nl O2/cm3 s, which is in the low range of V̇o2 values in skeletal muscle obtained in vivo and in vitro, including the measurements made in muscle fibers (Table 5). We found that local V̇o2 and Po2 values in resting muscle are heterogeneous, and no significant correlation was revealed between V̇o2 and baseline Po2. This correlation may be found in the case of continuous measurements of these two parameters during the Po2 decrease recorded at the same tissue site.

Table 5.

V̇o2 in resting muscles, tissue samples, and muscle fibers of small animals

| Muscle | V̇o2, nl O2/(cm3·s) | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat spinotrapezius | 267 | Fick principle | 6 |

| Rat soleus, peroneal | 367,167 | Fick principle | 37 |

| Rat gracilis | 167 | Fick principle | 28 |

| Rat gracilis | 187 | Polarographic | 12 |

| Rat extensor digitorum longus, soleus, diaphragm | 63, 47, 145 | Polarographic | 27 |

| Rat cremaster | 353 | Polarographic | 4 |

| Rat soleus, peroneal | 367, 167 | Fick principle | 7 |

| Rat hind limb muscles | 66 | Fick principle | 36 |

| Hamster retractor, sartorius, soleus | 139, 134, 146 | Polarographic | 17 |

| Hamster retractor, sartorius, soleus | 157, 141, 176 | Polarographic | 48 |

| Hamster retractor | 339 | Polarographic | 8 |

| Hamster retractor | 385–528 | Microelectrode | 16 |

| Hen gastrocnemius, pectoralis | 300, 72 | Polarographic | 4 |

Conclusion

We have developed a microscopic technique combining phosphorescence quenching oximetry and pneumatic tissue compression to obtain oxygen disappearance curves, practically independent of hemoglobin. This method allows immediate and continuous measurements of oxygen tension and oxygen consumption rate in situ in skeletal muscle and other tissues accessible to study using PQM. The method is nontraumatic and allows for good isolation of the tissue from stray oxygen using a gas barrier film. Tissue respirometry can be repeated in different regions of the same muscle during rest or in experiments, which affect the respiration rate.

GRANTS

This research is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-18292 and HL-79087 and from America Heart Association, Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Grant AHA-0655449U.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Acker H, Lubbers DW. The kinetics of local tissue Po2 decrease after perfusion stop within the carotid body of the cat in vivo and in vitro. Pflügers Arch 369: 135–140, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altman PL, Dittmer DS. Respiration and Circulation. Bethesda, MD: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 1971, p. 930 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey JK, Kindig CA, Behnke BJ, Musch TI, Schmid-Schoenbein GW, Poole DC. Spinotrapezius muscle microcirculatory function: effects of surgical exteriorization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H3131–H3137, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baranov VI, Belichenko VM, Shoshenko CA. Oxygen diffusion coefficient in isolated chicken red and white skeletal muscle fibers in ontogenesis. Microvasc Res 60: 168–176, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behnke BJ, Barstow TJ, Kindig CA, McDonough P, Musch TI, Poole DC. Dynamics of oxygen uptake following exercise onset in rat skeletal muscle. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 133: 229–239, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behnke BJ, Ferreira LF, McDonough PJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Recovery dynamics of skeletal muscle oxygen uptake during the exercise off-transient. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 168: 254–260, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Behnke BJ, McDonough P, Padilla DJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Oxygen exchange profile in rat muscles of contrasting fibre types. J Physiol 549: 597–605, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bentley TB, Meng H, Pittman RN. Temperature dependence of oxygen diffusion and consumption in mammalian striated muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H1825–H1830, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boegehold MA, Johnson PC. Periarteriolar and tissue Po2 during sympathetic escape in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 254: H929–H936, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buerk DG, Nair PK, Bridges EW, Hanley TR. Interpretation of oxygen disappearance curves measured in blood perfused tissues. Adv Exp Med Biol 200: 151–161, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cabrales P, Intaglietta M. Time-dependant oxygen partial pressure in capillaries and tissue in the hamster window chamber model. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 845–853, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chinet AE, Mejsnar J. Is resting muscle oxygen uptake controlled by oxygen availability to cells? J Appl Physiol 66: 253–260, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Copp SW, Ferreira LF, Herspring KF, Musch TI, Poole DC. The effects of aging on capillary hemodynamics in contracting rat spinotrapezius muscle. Microvasc Res 77: 113–119, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crank J. The mathematics of diffusion. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davies PW, Grenell RG. Metabolism and function in the cerebral cortex under local perfusion, with the aid of an oxygen cathode for surface measurement of cortical oxygen consumption. J Neurophysiol 25: 651–683, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dutta A, Wang L, Meng H, Pittman RN, Popel AS. Oxygen tension profiles in isolated hamster retractor muscle at different temperatures. Microvasc Res 51: 288–302, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ellsworth ML, Pittman RN. Heterogeneity of oxygen diffusion through hamster striated muscles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 246: H161–H167, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foote CS. Mechanisms of photooxygenation. Prog Clin Biol Res 170: 3–18, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gleichmann U, Ingvar DH, Lassen NA, Lubbers DW, Siesjo BK, Thews G. Regional cerebral cortical metabolic rate of oxygen and carbon dioxide, related to the EEG in the anesthetized dog. Acta Physiol Scand 55: 82–94, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Golub AS, Barker MC, Pittman RN. Po2 profiles near arterioles and tissue oxygen consumption in rat mesentery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1097–H1106, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Golub AS, Pittman RN. Po2 measurements in the microcirculation using phosphorescence quenching microscopy at high magnification. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2905–H2916, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Golub AS, Pittman RN. Thermostatic animal platform for intravital microscopy of thin tissues. Microvasc Res 66: 213–217, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Golub AS, Popel AS, Zheng L, Pittman RN. Analysis of phosphorescence in heterogeneous systems using distributions of quencher concentration. Biophys J 73: 452–465, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gray SD. Histochemical analysis of capillary and fiber-type distributions in skeletal muscles of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Microvasc Res 36: 228–238, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray SD. Morphometric analysis of skeletal muscle capillaries in early spontaneous hypertension. Microvasc Res 27: 39–50, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gray SD. Rat spinotrapezius muscle preparation for microscopic observation of the terminal vascular bed. Microvasc Res 5: 395–400, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hofmann WW. Oxygen consumption by human and rodent striated muscle in vitro. Am J Physiol 230: 34–40, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Honig CR, Frierson JL, Nelson CN. O2 transport and V̇o2 in resting muscle: significance for tissue-capillary exchange. Am J Physiol 220: 357–363, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kanofsky JR. Quenching of singlet oxygen by human plasma. Photochem Photobiol 51: 299–303, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kindig CA, Poole DC. A comparison of the microcirculation in the rat spinotrapezius and diaphragm muscles. Microvasc Res 55: 249–259, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klitzman B, Popel AS, Duling BR. Oxygen transport in resting and contracting hamster cremaster muscles: experimental and theoretical microvascular studies. Microvasc Res 25: 108–131, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kunze K, Lubbers DW. [Measurement of the local Po2 in organs in situ with platinum electrode]. Pflügers Arch 274: 74–75, 1961 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lash JM, Bohlen HG. Perivascular and tissue Po2 in contracting rat spinotrapezius muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 252: H1192–H1202, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leniger-Follert E. Direct determination of local oxygen consumption of the brain cortex in vivo. Pflügers Arch 372: 175–179, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mahler M, Louy C, Homsher E, Peskoff A. Reappraisal of diffusion, solubility, and consumption of oxygen in frog skeletal muscle, with applications to muscle energy balance. J Gen Physiol 86: 105–134, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marshall JM, Davies WR. The effects of acute and chronic systemic hypoxia on muscle oxygen supply and oxygen consumption in the rat. Exp Physiol 84: 57–68, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDonough P, Behnke BJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Recovery of microvascular Po2 during the exercise off-transient in muscles of different fiber type. J Appl Physiol 96: 1039–1044, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mitra S, Foster TH. Photochemical oxygen consumption sensitized by a porphyrin phosphorescent probe in two model systems. Biophys J 78: 2597–2605, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moe SM, Lai-Fook SJ. Effect of concentration on restriction and diffusion of albumin in the excised rat diaphragm. Microvasc Res 65: 96–108, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nair PK, Buerk DG, Halsey JH., Jr Comparisons of oxygen metabolism and tissue Po2 in cortex and hippocampus of gerbil brain. Stroke 18: 616–622, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pittman RN, Golub AS, Popel AS, Zheng L. Interpretation of phosphorescence quenching measurements made in the presence of oxygen gradients. Adv Exp Med Biol 454: 375–383, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reneau DD, Guilbeau EJ, Null RE. Oxygen dynamics in brain. Microvasc Res 13: 337–344, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Richmond KN, Shonat RD, Lynch RM, Johnson PC. Critical Po2 of skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1831–H1840, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roy CS, Brown JG. The blood-pressure and its variations in the arterioles, capillaries and smaller veins. J Physiol 2: 323–446, 1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shibata M, Ichioka S, Ando J, Kamiya A. Microvascular and interstitial Po2 measurements in rat skeletal muscle by phosphorescence quenching. J Appl Physiol 91: 321–327, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shonat RD, Wilson DF, Riva CE, Pawlowski M. Oxygen distribution in the retinal and chroidal vessels of the cat as measured by a new phosphorescence imaging method. Appl Opt 31: 3711–3718, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith LM, Golub AS, Pittman RN. Interstitial Po2 determination by phosphorescence quenching microscopy. Microcirculation 9: 389–395, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sullivan SM, Pittman RN. In vitro O2 uptake and histochemical fiber type of resting hamster muscles. J Appl Physiol 57: 246–253, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thorpe WH, Crisp DJ. Studies on plastron respiration; the respiratory efficiency of the plastron in Aphelocheirus. J Exp Biol 24: 270–303, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Torres Filho IP, Intaglietta M. Microvessel Po2 measurements by phosphorescence decay method. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H1434–H1438, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Torres Filho IP, Leunig M, Yuan F, Intaglietta M, Jain RK. Noninvasive measurement of microvascular and interstitial oxygen profiles in a human tumor in SCID mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 2081–2085, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vanderkooi JM, Erecinska M, Silver IA. Oxygen in mammalian tissue: methods of measurement and affinities of various reactions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 260: C1131–C1150, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vanderkooi JM, Maniara G, Green TJ, Wilson DF. An optical method for measurement of dioxygen concentration based upon quenching of phosphorescence. J Biol Chem 262: 5476–5482, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whalen WJ, Nair P, Buerk D, Thuning CA. Tissue Po2 in normal and denervated cat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol 227: 1221–1225, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Whalen WJ, Nair P, Sidebotham T, Spande J, Lacerna M. Cat carotid body: oxygen consumption and other parameters. J Appl Physiol 50: 129–133, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whalen WJ, Riley J, Nair P. A microelectrode for measuring intracellular Po2. J Appl Physiol 23: 798–801, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wilson DF, Lee WM, Makonnen S, Finikova O, Apreleva S, Vinogradov SA. Oxygen pressures in the interstitial space and their relationship to those in the blood plasma in resting skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 101: 1648–1656, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wilson DF, Vanderkooi JM, Green TJ, Maniara G, DeFeo SP, Bloomgarden DC. A versatile and sensitive method for measuring oxygen. Adv Exp Med Biol 215: 71–77, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zheng L, Golub AS, Pittman RN. Determination of Po2 and its heterogeneity in single capillaries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H365–H372, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]