ABSTRACT

Clinically silent corticotroph tumors of the pituitary gland are those tumors that stain for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) but do not manifest with clinical or laboratory features of Cushing disease. These tumors have been described as exhibiting more aggressive behavior than other nonfunctional pituitary tumors. We present an unusual case of a clinically silent corticotropic adenoma of the pituitary gland that underwent cystic degeneration following recurrence after transsphenoidal surgery and radiation therapy. The patient underwent left frontotemporal craniotomy with resection of the suprasellar mass and decompression of the left optic nerve. Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated no further optic chiasm or nerve compression. Patients with clinically silent ACTH-secreting tumors should be monitored for aggressive tumor behavior and may require closer follow-up than those patients harboring other nonfunctional tumors.

Keywords: Cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, nonfunctional pituitary adenoma, corticotroph cells, Cushing disease, cystic degeneration

Pituitary adenomas that are clinically silent but stain positive for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) were first described in detail in 1980.1 Since that initial report, there have been a few small series evaluating these clinically silent corticotroph tumors,2,3,4,5,6 which represent ∼5 to 7% of nonfunctional pituitary tumors and 43% of ACTH-secreting tumors.6,7 These series provide evidence that such tumors have a tendency to behave more aggressively than other pituitary tumors. Recent evidence has also suggested that clinically silent pituitary tumors that stain positive for ACTH may also have the potential to evolve into clinical Cushing disease.6,7,8,9

We present an unusual case of a clinically silent corticotropic adenoma of the pituitary gland that underwent symptomatic cystic degeneration following recurrence after transsphenoidal surgery and radiation therapy.

CASE REPORT

History and Presentation

A 68-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of progressive visual loss in his left eye and no other significant neurological or endocrinological symptoms. On examination, he demonstrated markedly diminished visual acuity in his left eye with a field cut involving both the temporal and the nasal upper quadrants. Funduscopic examination revealed some retinal pallor. His examination was otherwise unremarkable. His preoperative endocrinological workup was remarkable only for minimally elevated serum prolactin (21.5 ng/mL, normal 2.1 to 17.7) and low testosterone (174 ng/dL, normal 350 to 720, free = 22.9 pg/mL, normal 47 to 244). His serum cortisol and ACTH levels were normal.

Imaging

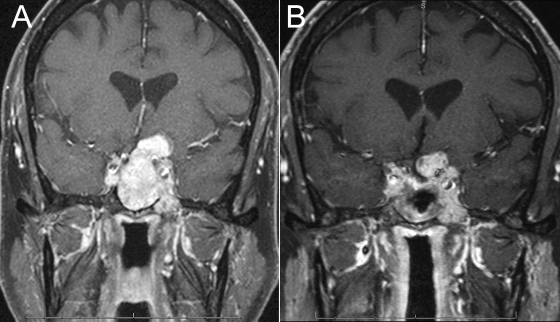

The patient underwent magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which demonstrated a large sellar mass with bony erosion extending into the clivus, a significant suprasellar component, and compression of the left optic nerve (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Preoperative MR imaging demonstrating a large sellar mass with bony erosion extending into the clivus, a large suprasellar component, and compression of the left optic nerve; (B) initial postoperative MR imaging demonstrating expected residual tumor in the left suprasellar space and cavernous sinus.

Operation

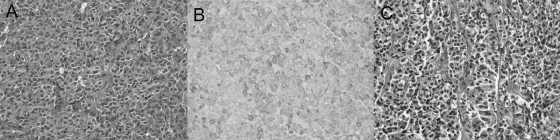

The patient underwent subtotal transsphenoidal resection of the mass. Pathological examination was consistent with a pituitary adenoma with positive staining for ACTH. There were no significant mitotic figures (Fig. 2A, B).

Figure 2.

Histological studies from initial resection showing chromophobic staining and mixed sinusoidal/diffuse growth patterns with hematoxylin and eosin stain (A) and positive ACTH immunostaining (B). Residual tumor again demonstrated pituitary adenoma with positive staining for ACTH and no significant mitotic figures (C).

Postoperative Course

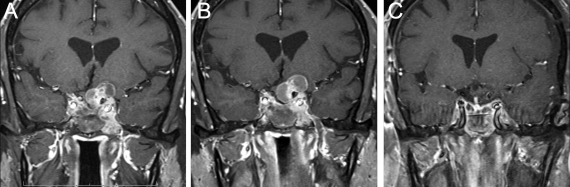

The patient enjoyed significant postoperative improvement in his visual symptoms. At 6-month follow-up, there was expected residual tumor in the left suprasellar space and in the cavernous sinus (Fig. 1B). The patient was offered referral for radiation therapy and underwent treatment with a total dose of 5040 cGy in 28 fractions. He had no side effects from his radiation therapy. Follow-up imaging over the next 6 months demonstrated stable tumor size, but 1 year after surgery there was evidence of slight enlargement. Because no clinical change was associated with the enlargement, close monitoring was continued. The results of ophthalmologic examinations remained stable, but continued enlargement with cystic degeneration was demonstrated over the following year, with progressive compression of the optic chiasm and left optic nerve (Fig. 3A, B). The patient underwent left frontotemporal craniotomy with resection of the suprasellar mass and decompression of the left optic nerve. Postoperative MR imaging demonstrated no further optic chiasm or nerve compression (Fig. 3C). Pathological analysis of the resected mass again demonstrated pituitary adenoma with positive staining for ACTH and no significant mitotic figures (Fig. 2C). At 1-year follow-up after his most recent surgery, he continues to do well without evidence of tumor progression on MR imaging.

Figure 3.

Coronal MR imaging scans showing enlargement with cystic degeneration (A); progression (B); and postoperative (C).

DISCUSSION

Since the landmark description of clinically silent corticotroph tumors of the pituitary gland by Horvath et al,1 these lesions have received attention in the literature because of reports of particularly high aggressiveness, including high rates of infarction/apoplexy3,4 and high recurrence rates.1,4,5 Bradley et al2 presented a series of 28 patients with ACTH-staining nonfunctional pituitary adenomas, whom they compared with similar patients whose nonfunctional tumors stained negative for ACTH. Although they found a similar recurrence rate between the two groups (32% for ACTH-positive patients compared with 33% for ACTH-negative patients), two of their ACTH-positive patients who suffered recurrence had multiple recurrences, including one with two recurrences, requiring three surgeries and two courses of radiation treatment. The other had three recurrences, necessitating four operations, two radiation treatments, and gamma knife therapy. This contrasted sharply with the ACTH-negative group, in which no patients required more than one additional treatment for recurrence. This led the authors to conclude that, although clinically silent ACTH-secreting tumors do not recur more frequently, they may be more likely to behave in a much more aggressive manner when they do recur.

The authors of other studies have found a tendency for these tumors to have a higher rate of recurrence than other nonfunctional pituitary tumors.1,4,5 Scheithauer et al4 presented a series of 23 clinically silent corticotroph tumors, all of which were macroadenomas and frequently presented with symptoms of mass effect. The authors also found suprasellar extension in 87% of these tumors and aggressive features such as hemorrhage, cystic changes, or necrosis in 61%. Fifty-four percent of their patients with at least 3 years of follow-up demonstrated either persistent or recurrent tumors. Similarly, Webb et al5 reported the cases of 27 such patients and found apoplexy in 9 (33%), suprasellar extension in 21 (78%), and cavernous sinus involvement in 13 (48%). Follow-up monitoring demonstrated recurrence in 10 (37%).

A tendency of these tumors to cause Cushing disease later in their course has been suggested by the authors of some studies. Baldeweg et al6 reported an 86.7% rate of visual deficits at presentation of patients with clinically silent corticotroph tumors. They also found that four of 22 patients later developed hypercortisolism. Vaughan et al8 also reported a patient who developed Cushing disease after initial presentation and was found to have ACTH staining both before and after development of Cushing disease. Other reports of patients with nonfunctional tumors who later develop Cushing disease7,9 and the observation of elevated ACTH levels in the absence of clinical Cushing disease in such tumors4,10 suggest that there may be a spectrum of disease that is as yet poorly characterized.

Pathologic features of clinically silent corticotroph tumors were described in the report of Horvath et al.1 In this series, the authors described groups of tumors exhibiting distinct light microscopic and ultrastructural features. This has led to the description of two well-defined pathological subtypes.1,3,4,11 The first group (type I) involves tumors that tend to be basophilic, with strong periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and lead–hematoxylin staining and a sinusoidal pattern similar to that seen in ACTH-secreting tumors. The second group (type II) includes tumors that are more chromophobic, with variable PAS and lead–hematoxylin staining. They tend to be arranged in a more diffuse pattern, with some exhibiting sinusoidal arrangements of cells. Our patient would be classified as type II. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, the cells had an amphophilic or chromophobic staining quality. ACTH staining showed a heterogeneous pattern, with ∼50% of cells showing weak-to-moderate amounts of staining (Fig. 2).

In a study of 12 patients, Lopez et al3 found eight patients with type I tumors (variably basophilic cytoplasm) and four with type II (chromophobic cytoplasm). Two of their patients developed apoplexy and two “mimicked craniopharyngioma.” They also described two patients with acute cortisol insufficiency. Among 23 patients evaluated by Scheithauer et al,4 16 were type I and seven were type II. These authors found a stronger male predominance in type II tumors than in type I tumors (M:F = 6:1 for type II and 1.7:1 for type I). They also found a higher rate of apoplexy in type II tumors (14% versus 6%) and a higher rate of persistence or recurrence in type I tumors (63% versus 40%), although these differences were not statistically significant.

Indeed, no investigators to date have been able to find a strong correlation between the pathological features of clinically silent corticotroph tumors and their aggressiveness. In the study of Baldeweg et al,6 the authors evaluated the mitotic activity and Ki-67 labeling features and compared them with the tumors’ recurrence rates. They found no relationship. This observation corresponds to our patient, whose tumor exhibited aggressive features clinically but demonstrated no abnormal mitotic activity at either of his operations.

CONCLUSION

There is an increasing body of evidence supporting the notion that clinically silent corticotroph tumors may behave more aggressively than other nonfunctional tumors. We present an unusual case of marked cystic enlargement of a clinically silent ACTH-secreting tumor after surgical and radiation therapy. Further research is needed to characterize the behavior of such tumors more fully; however, patients with clinically silent ACTH-secreting tumors should be monitored for aggressive tumor behavior and may require closer follow-up than those patients harboring other nonfunctional tumors. Our practice is to monitor such tumors for recurrence or progression with MR imaging at a maximum of 6-month intervals for the first few years after resection. In reliable patients with stable imaging, the follow-up monitoring can then sometimes be extended to 1-year intervals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kristin Kraus, M.Sc., for editorial assistance in preparing this paper and Steven Chin, M.D., Ph.D., for assistance with the pathologic classification and preparation of the slides.

REFERENCES

- Horvath E, Kovacs K, Killinger D W, Smyth H S, Platts M E, Singer W. Silent corticotropic adenomas of the human pituitary gland: a histologic, immunocytologic, and ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1980;98(3):617–638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K J, Wass J A, Turner H E. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas with positive immunoreactivity for ACTH behave more aggressively than ACTH immunonegative tumours but do not recur more frequently. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58(1):59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J A, Kleinschmidt-Demasters B K, Sze C I, Woodmansee W W, Lillehei K O. Silent corticotroph adenomas: further clinical and pathological observations. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(9):1137–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheithauer B W, Jaap A J, Horvath E, et al. Clinically silent corticotroph tumors of the pituitary gland. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(3):723–729. discussion 729–730. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200009000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb K M, Laurent J J, Okonkwo D O, Lopes M B, Vance M L, Laws E R., Jr Clinical characteristics of silent corticotrophic adenomas and creation of an internet-accessible database to facilitate their multi-institutional study. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(5):1076–1084. discussion 1084–1085. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000088660.16904.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldeweg S E, Pollock J R, Powell M, Ahlquist J. A spectrum of behaviour in silent corticotroph pituitary adenomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19(1):38–42. doi: 10.1080/02688690500081230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado L R, Machado M C, Cukiert A, Liberman B, Kanamura C T, Alves V A. Cushing’s disease arising from a clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma. Endocr Pathol. 2006;17(2):191–199. doi: 10.1385/ep:17:2:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan N J, Laroche C M, Goodman I, Davies M J, Jenkins J S. Pituitary Cushing’s disease arising from a previously non-functional corticotrophic chromophobe adenoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1985;22(2):147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1985.tb01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E U, Ho M S, Rajasoorya C R. Metamorphosis of a non-functioning pituitary adenoma to Cushing’s disease. Pituitary. 2000;3(2):117–122. doi: 10.1023/a:1009961925780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Taniyama M, Xu B, et al. Silent mixed corticotroph and somatotroph macroadenomas presenting with pituitary apoplexy. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102(5):435–440. doi: 10.1007/s004010100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath E, Kovacs K, Smyth H S, et al. A novel type of pituitary adenoma: morphological features and clinical correlations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66(6):1111–1118. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-6-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]