ABSTRACT

The objective is to correlate the intracavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) with the position of the intracavernous neural structures. The cavernous sinuses of nine injected cadaveric heads were dissected bilaterally. As measured on computed tomographic angiograms from 100 adults, anatomical relationships and measurements of intracavernous ICA and neural structures were studied and correlated to the intracavernous ICA curvature. Intracavernous ICAs were classified as normal and redundant. The meningohypophyseal trunk (MHT) of normal ICAs appeared to be closely related to the abducens nerve compared with redundant ICAs (5.5 ± 2.1 mm versus 10.0 ± 2.5 mm, respectively; p = 0.001). The position of the inferolateral trunk (ILT) varied along the horizontal segment of the intracavernous ICA. On imaging studies the ICA curvature correlated with the kyphotic degree of the skull and similarity of the ICA curvature between sides. The safety margin for preventing iatrogenic intracavernous nerve injury during surgical exploration or transarterial embolization of vascular lesions around the MHT is high with redundant ICAs. In contrast, a transvenous endovascular approach via the inferior petrosal sinus may be too distant to reach the MHT when ICAs are redundant. Approaching lesions of the inferolateral trunk may be the same regardless of ICA type.

Keywords: Abducens nerve, carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous sinus anatomy, internal carotid artery, sympathetic nerve

The cavernous sinus is one of the most complex and challenging areas for skull base surgery. Vascular diseases in this region usually involve both the arterial and venous systems (e.g., carotid-cavernous fistulas, CCFs). The complex venous channels and deep anatomical location make surgical or endovascular exploration of this region difficult. The multitude of cranial nerves passing through the sinus demands precise surgical trajectories. Endovascular treatment provides an alternate corridor and may be a more efficacious treatment option for particular diseases in this region.

The anatomical relationships of the cavernous sinus have been described extensively.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 However, no study has described the consequences of treatment of the curved segments of the intracavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) in relation to intracavernous neural structures. Such information may provide insights for selecting treatment approaches to vascular pathologies of the cavernous sinus. We therefore sought to define anatomical data of the intracavernous ICA and related neural structures and to correlate the former with relevant radiologic data, especially as related to the skull base and curvature of the ICA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cadaveric Dissection

Nine injected cadaveric heads were dissected bilaterally through the pretemporal orbitozygomatic approach. The cavernous sinuses were exposed as described elsewhere.10,11 The anterior clinoid processes were removed to expose the cavernous roof and to free the neurovascular structures. The oculomotor nerve was preserved. The proximal dural ring was identified as the exit site of the intracavernous ICA. The cavernous sinuses were opened in the roof and lateral wall to expose the intracavernous structures. Injected silicone was removed piece by piece from the cavernous sinus to identify intracavernous structures and venous spaces.

The anatomical variability of the intracavernous ICA and associated branches was noted along with relationships to intracavernous neural structures. As described by Inoue et al,2 the intracavernous ICA was divided into five segments based on morphological features: (1) posterior vertical segment, (2) posterior bend, (3) horizontal segment, (4) anterior bend, and (5) anterior vertical segment.

We classified the curvature of the ICA as normal and redundant. In a normal-type ICA, a horizontal segment ran horizontally or curved superiorly. In the redundant type, a posterior bend coursed higher than the horizontal segment, resulting in a tortuous configuration.

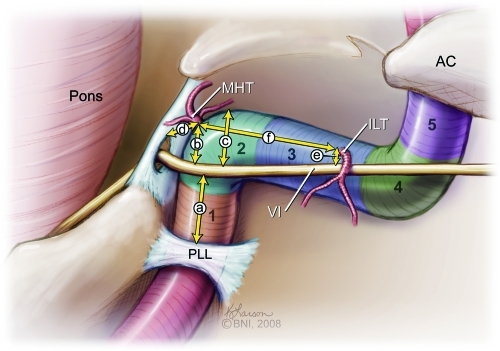

The exposure of the intracavernous ICA was completed by additional extradural dissection through the middle fossa approach. The mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve was divided to expose the proximal cavernous sinus. The proximal entry point of the ICA into the cavernous sinus was identified on the petrolingual ligament (PLL). The following six distances were then measured (Fig. 1): (1) from the PLL to the abducens nerve (CN VI), (2) from CN VI to the meningohyphoseal trunk (MHT), (3) from CN VI to the highest point of the posterior bend of the intracavernous ICA (max), (4) from the MHT to Dorello's canal, (5) from CN VI to the inferolateral trunk (ILT), and (6) from MHT to ILT. When the MHT or ILT had multiple origins, the closest distance between two anatomical points was measured.

Figure 1.

Illustration shows segments of intracavernous ICA: (1) posterior vertical, (2) posterior bending, (3) horizontal, (4) anterior bending, and (5) anterior vertical. AC, anterior clinoid process; ILT, inferolateral trunk; MHT, meningohypophyseal trunk; PLL, petrolingual ligament; VI, abducens nerve. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Radiographic Study

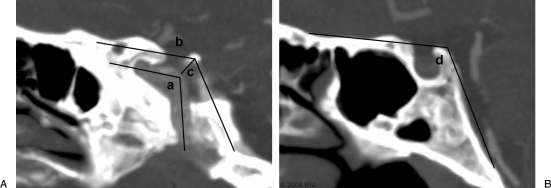

Sagittal computed tomographic angiograms (CTAs) from 100 adult patients (200 ICAs) who were at least 15 years old were examined. Images from 69 females and 31 males (mean and median age 56 years) were evaluated. No intracavernous bony or vascular lesions in the cavernous sinus were detected in these patients. Clear-cut limitations in identifying the soft tissues in imaging studies required a different measurement strategy than used in the cadavers. The parasagittal cut, which is best suited to show the posterior bend segment, was used to measure three parameters (Fig. 2). We defined the ICA curve angle as the angle formed by the junction of the axes of the posterior vertical segment with the axis of the horizontal segment. The cavernous roof angle was defined by connecting the imaginary plane on the cavernous roof to the plane on the posterior wall of the cavernous sinus on the same parasagittal cut. The posterosuperior venous space was estimated by measuring the distance between the highest point of the posterior bend and the cavernous roof. Sagittal cuts were also evaluated for the midline basal angle, which was measured from the anterior cranial fossa to the tip of the dorsum sellae connecting the line along the posterior margin of the clivus as described elsewhere.12

Figure 2.

Radiologic studies evaluating the ICA curvature and cavernous sinus: (A) parasagittal cut for the ICA curve angle (a), the cavernous roof angle (b), and the posterosuperior venous space (c). (B) Sagittal cut for the midline basal angle (d). This patient has an ICA with a normal curvature. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

The redundancy of the intracavernous ICA was defined as when the ratio of the ICA curve angle and cavernous roof angle was less than 0.5. Thus, stratification was created in three groups of patients: bilateral redundant ICA, unilateral redundant ICA, and bilateral normal ICA. This stratification was performed to identify parameters associated with the redundancy of the ICA.

Statistical Analysis

Measurements and quantitative data were acquired using the Stealth TREON Plus Navigation System (Medtronic, Louisville, CO). Anatomical targets were registered with the tip of a navigating probe. All retrieved coordinate data were entered into a spreadsheet for analysis with a custom-made program (Spherical Area; Microsearch, Bitwise Ideas Inc., Fredericton, NB, Canada). Calculated length and angle data were presented as means and standard deviations (SDs). Comparisons of anatomical distances between two types of ICAs were evaluated by a Student's t-test. Comparisons among patients with bilateral redundant ICA, unilateral redundant ICA, and bilateral normal ICA were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Holm-Sidak pairwise comparisons. In case normality failed, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's method was used instead. The relationships among ICA curve angle, cavernous roof angle, and midline basal angle were analyzed with Pearson's correlation coefficients. All statistical calculations were performed with SigmaStat 3.5 program (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA). A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The distances corresponding to CN VI and MHT, to CN VI and max, and to MHT and Dorello's canal were significantly different between specimens with normal and redundant ICAs (Table 1). However, there were no significant differences in the distances represented by PLL-CN VI, CN VI-ILT, or MHT-ILT when specimens with normal and redundant ICAs were compared.

Table 1.

Anatomical Measurements of Intracavernous Structures in 12 Normal and 6 Redundant ICAs

| Anatomical Distance | Normal ICA (mm ± SD) | Redundant ICA (mm ± SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN VI, abducens nerve; ICA, internal carotid artery; ILT, inferolateral trunk; Max, highest point of the posterior bend of the intracavernous ICA; MHT, meningohypophyseal trunk; PLL, petrolingual ligament. | |||

| PLL-CN VI | 6.0 ± 3.2 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 0.982 |

| CN VI-MHT | 5.5 ± 2.1 | 10.0 ± 2.5 | 0.001 |

| CN VI-Max | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 12.1 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| MHT-Dorello's | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| CN VI-ILT | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 0.624 |

| MHT-ILT | 5.3 ± 2.6 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 0.509 |

Intracavernous Vascular Structures

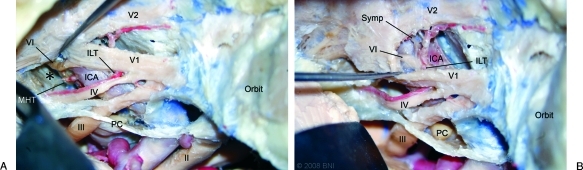

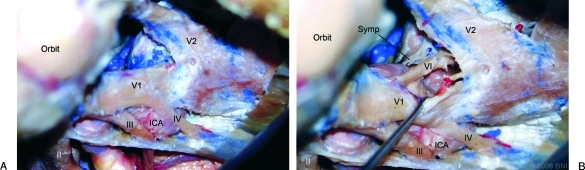

The normal-type curvature was observed in six specimens (12 sides, Fig. 3). The redundant-type curvature was observed in three specimens (six sides, Fig. 4). In all specimens, the pattern of curvature was similar on both sides.

Figure 3.

Left-sided dissection of normal ICA specimen: (A) Posterosuperior window shows large posterosuperior venous space (*, injected silicone removed) and the close relationship between the meningohypophyseal trunk (MHT) and the abducens nerve (VI). (B) Excessive retraction is required to reach the origin of the inferolateral trunk (ILT) from the anteroinferior window. II, optic nerve; III, oculomotor nerve; IV, trochlear nerve; PC, posterior clinoid process; Symp, sympathetic fibers; V1, ophthalmic nerve; V2, maxillary nerve. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Figure 4.

Right-sided dissection of redundant ICA specimen: (A) Redundant posterior bend results in the volume of the posterosuperior venous space being small. The abducens nerve (VI) is not exposed from the posterosuperior window. (B) The anteroinferior window with retraction of V1 (ophthalmic nerve). The abducens nerve and sympathetic fibers (Symp) are exposed in this view. The tip of the probe is on the ILT. II, optic nerve; III, oculomotor nerve; IV, trochlear nerve; V2, maxillary nerve. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

In none of our specimens did the MHT and ILT share a common origin. No persistent trigeminal artery was identified. In all specimens, the ophthalmic artery arose from the extracavernous portion of the ICA.

The intracavernous ICA gave rise to the MHT in all specimens. The MHTs were observed as a single trunk in nine of 18 sides. The single trunk usually gave rise to three or four secondary branches (e.g., the tentorial artery, dorsal clival artery, and inferior hypophyseal artery) that supplied the nearby cranial nerves and tentorium. In the remaining nine specimens, these branches emerged directly from the intracavernous ICA. The maximal number of direct branches from the ICA was three. The inferiorly located branches were always the dorsal clival or inferior hypophyseal arteries, whereas the superiorly located branch was the tentorial artery. Altogether, 29 origins emerged from the posterosuperior aspect of the intracavernous ICA at the posterior bend surrounded by the posterosuperior venous space of the cavernous sinus. In one cavernous sinus, the tentorial artery originated directly from the superior aspect of the horizontal segment.

The ILT was present in all specimens. It occurred as a single trunk in 15 of the 18 sides. All ILTs were located in the lateral aspect of the horizontal segment of the intracavernous ICA. The ILT gave rise to three to four branches that supplied the nearby cranial nerves and tentorium. Separate branchings (two origins) were found in the remaining three sides.

Intracavernous Neural Structures

CN VI entered the cavernous sinus via Dorello's canal under the petrosphenoidal ligament (Gruber's ligament). No splitting of this nerve was observed. It coursed medial to the ophthalmic nerve and lateral to the posterior bend or posterior vertical segment of the ICA. CN VI continued running medial to the ophthalmic nerve in the cavernous sinus before it exited through the superior orbital fissure.

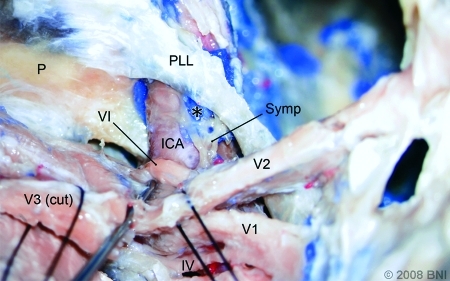

The sympathetic trunk, a network of neural fibers, adhered to the petrous segment of the ICA. However, after the ICA passed through the PLL becoming the posterior vertical segment, the sympathetic fibers were observed mainly in the anterior part departing from the artery and covering near the dural wall. Before the ICA approached CN VI, most of the visible fibers were located anteroinferior to the artery. The sympathetic fibers then ran together with the ophthalmic nerve. No redundant curvature of the sympathetic pathway was observed to be associated with redundant ICAs (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Left-sided dissection with division of the mandibular nerve (V3) and partial removal of the lateral cavernous wall exposing the petrolingual ligament (PLL) and posterior vertical segment of the intracavernous segment of the ICA. The sympathetic fibers (Symp) exit the ICA and approach the abducens nerve (VI). (*, injected silicone interposed between the sympathetic fibers and ICA). P, petrous apex; IV, trochlear nerve; V1, ophthalmic nerve; V2, maxillary nerve. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Anatomical Observations

From a superolateral view, the intracavernous ICA can be observed proximally from the posterior vertical segment above the ophthalmic nerve to its distal portion before it exits the cavernous sinus via two major windows: the posterosuperior and anteroinferior.

POSTEROSUPERIOR WINDOW

This window included both supra- and infratrochlear triangles (Figs. 3A and 4A). In most specimens the infratrochlear triangle appeared to be bigger than the supratrochlear triangle. The posterosuperior venous space seemed to be larger when ICAs had a normal curvature compared with redundant ICAs. The MHTs were usually accessible through this window. In four of the six sides with a redundant ICA, however, the lower branches of the MHTs were obstructed by the ICA itself. Approaching the origin of the ILT was even more difficult due to its position near the lateral wall in the distal portion of the cavernous sinus. In most specimens this branch was just above CN VI (21 of 24 origins). Only in 3 of 24 origins did the ILTs emerge below CN VI. To expose the ILT, retracting the ophthalmic nerve laterally or the ICA medially was required.

CN VI was visible entering Dorello's canal in 7 of the 18 sides without excessive retraction. In all seven specimens in which Dorello's canals could be approached directly, the ICA had a normal curvature. In the remainder, considerable retraction of the ICA or lateral wall was needed to expose Dorello's canal.

ANTEROINFERIOR WINDOW

This window is located between the ophthalmic and maxillary nerves (Figs. 3B and 4B). Venous space in this area was continuous with the orbital venous pathway. In all specimens with a redundant ICA, the anterior bend of the ICA was easily observed. In one specimen, ILT could be approached through this window without excessive retraction. In that case, however, the ILT originated below CN VI. In most cases, excessive retraction of the ophthalmic nerve was required. CN VI obstructed access to the origin of the ILT.

Radiographic Analysis

Patients were stratified into three groups as described. Bilateral redundant ICA curvature was identified in 18 of 100 patients. Unilateral redundant ICA curvature was observed in 19 patients. ICAs with a bilateral normal curvature were identified in 63 patients. Thus, the total number of redundant ICAs was 55 of 200 (27.5%). There was no significant difference in age among the groups (p = 0.983). The ICA curve angle and the cavernous roof angle (the ratio representing the redundancy of the ICA) were significantly different among the groups (p < 0.001). However, there were no differences in the midline basal angle (p = 0.148, Table 2).

Table 2.

Radiological Redundancy Comparisons

| Variables | Bilateral Redundant ICAs (18 Patients) | Unilateral Redundant ICAs (19 Patients) | Bilateral Normal ICAs (63 Patients) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 83% | 63% | 67% | - |

| Posterosuperior venous space >0.5 | 0% | 10.5%‡ | 54.0% | - |

| Median age | 57 | 56 | 56 | 0.983 |

| Median ICA curve angle | 23.5 | 60.6 | 115.2 | <0.001* |

| Mean cavernous roof angle | 115.4 ± 9.7 | 119.5 ± 11.4 | 126.4 ± 10.9 | <0.001† |

| Median midline basal angle | 114.5 | 114.8 | 117.5 | 0.148 |

Pairwise comparisons found significant differences among all groups (p < 0.05).

Pairwise comparisons found significant differences among all groups (p < 0.001).

All cases were from normal ICA side.

The ICA curve angle correlated weakly with both the cavernous roof and midline basal angles (r = 0.563 and 0.253, respectively). The correlation between type of ICA in the two sides of a specimen was high (r = 0.722, Table 3).

Table 3.

Radiological Correlation of the ICA Curve Angle, Cavernous Roof Angle, and Midline Basal Angle

| Imaging Parameters | No. | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICA curve angle–cavernous roof angle | 200 | 0.563 | <0.001 |

| ICA curve angle–midline basal angle | 200 | 0.253 | <0.001 |

| Left ICA curve angle–right ICA curve angle | 100 | 0.722 | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

The cavernous sinus is a cuboidal structure on both sides of the parasellar region with interconnections between the sides. The roof is formed by the membranous dural layer, the oculomotor nerve, and the medial part of the sphenoid wing, including the anterior clinoid process. The lateral wall is formed by two layers of dura loosely attached to each other: a thick outer layer continuous with the tentorium and a thin inner layer. The oculomotor, trochlear, and trigeminal nerves run between these two dural layers.

Advances in cranial base microsurgery and endovascular treatments have provided complementary multidirectional access to the intracavernous ICA. Thus, this region can now be accessed routinely. Knowledge of the surgical anatomy in this area improves surgeons' ability to localize symptoms and plan treatments.

Intracavernous Vascular Structures

Although there is no consensus on how the ICA should be classified,13,14,15,16 the goal of this study was not to propose a new classification. We primarily studied only the intracavernous segment of the ICA. The nomenclature for the curvatures and segments of the intracavernous ICA that we adopted were previously used by Inoue et al.2 These curves and segments are the consequence of how the middle cranial fossa develops.7 The segments that involve most vascular pathologies are the posterior bend and horizontal segment where intracavernous branching occurs. These segments also tend to be involved in traumatic cases.17

The major branches of the intracavernous carotid artery, the MHT and ILT, supply the intracavernous cranial nerves.18,19 Anastomosed irrigation among the MHT, ILT, and external carotid artery has been confirmed. The inverse relationship between the size of the MHT and ILT ensures a complementary blood supply to nearby structures.4

The MHT originates from the posterosuperior part of the posterior bend. A single MHT pattern followed by a trifurcation, namely, the tentorial artery (artery of Bernasconi-Cassinari), dorsal meningeal artery, and inferior hypophyseal artery, has been a relatively consistent finding.20 Lasjaunias and Moret21 described the direct origin of these arteries from the ICA instead of a true MHT configuration. Differences in branching have also been reported.4,19

The MHT usually emerges from the ICA as it did in all of our specimens.19 We also found variations in the origin of the MHT branches. However, the inferiorly located branches were the dorsal meningeal and inferior hypophyseal arteries. The superior branch was the tentorial artery.

The ILT arises from the lateral aspect of the horizontal segment. It usually gives rise to three or four secondary branches supplying the dura and cranial nerves in the region of the cavernous sinus.4,19,22 It was identified in 65 to 80% of the specimen in previous reports.18,19 However, this vessel was present in all of our specimens. The origins and branching of the ILT are more variable compared with those of the MHT.22 We found 87.5% of the ILT origins just superior to the abducens nerve comparable to this finding in 96% of the specimens of Inoue et al.2

We could not illustrate the microconfiguration of the venous compartment in our study. The existence of a trabeculated venous channel or a plexus of veins (not considered a true sinus) has been proposed but remains unsubstantiated.1,5,7,23,24 Compartmentalization with branching and venous channels can easily be mistaken for connective tissue or sympathetic fibers.

Types of Intracavernous ICA Curvature

Based on the anatomical dissections, the difference between the normal and redundant ICAs was reflected by the distance between the intersection of CN VI and the most posterior bend (6.7 ± 2.2 mm versus 12.1 ± 1.6 mm, p < 0.001). For redundant ICAs, the MHT was located a high near the posterior bend (5.5 ± 2.1 mm versus 10.0 ± 2.5 mm, p = 0.001). Therefore, the position of the MHT was closely related to the arterial configuration.

The origin of the ILT varied along the horizontal segment of the intracavernous ICA. This variation may be independent of the type of ICA. The closest mean distance from the intersection between CN VI and normal ICAs was 3.7 ± 2.1 mm and 4.2 ± 2.4 mm with redundant ICAs (p = 0.624).

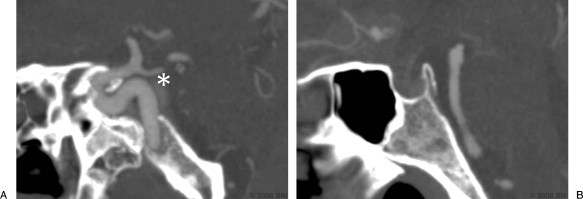

A redundant ICA was present in 27.5% of the 100 CT angiograms in our study. Interestingly, no relationship was found between the types of ICA curvature and age. The curvature of the intracavernous ICA weakly correlated with the configuration of the cavernous sinus, which reflected the kyphotic curvature of the skull base. A redundant curvature was common when the cavernous sinus was steep or the skull base was kyphotic. The midline basal angle alone could not precisely predict the configuration of the cavernous sinus. Parasagittal and/or coronal images were needed to predict the three-dimensional configuration of the ICA (Table 3). The configuration of the ICA curvature on one side predicted the curvature of the contralateral ICA. In most cases this arterial redundancy and the steep kyphotic angle of the cavernous sinus decreased the size of the posterosuperior venous space (Table 3, Figs. 4A and 6).

Figure 6.

(A) Parasagittal and (B) sagittal CTAs in a patient with a redundant ICA curvature. A small posterosuperior venous space (*) is visible. (Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Intracavernous Neural Structures

The distance of the ICA from the PLL to the intersection of CN VI seemed to be similar for both normal and redundant ICAs (p = 0.982). This finding indicates that the configuration of CN VI is more closely related to the bony anatomy than to the arterial curvature.

The sympathetic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion traveled with the ICA. As reported earlier,1,25,26,27 these fibers diverged from the intracavernous ICA to adhere to CN VI while crossing it to join the ophthalmic nerves. van Overbreeke28 systematically described the intracavernous sympathetic pathways. Multiple bundles of sympathetic pathways have been defined. In our study, however, the obvious sympathetic bundle that could be observed was inferolateral to the horizontal segment.

The cavernous and intracranial portions of the ICA are more variable than the petrous portion. Consequently, the locations of the intracavernous and intracranial ICA curvatures also vary. In contrast, the cranial nerves course directly to exit in their own cranial foramina. Even though the sympathetic plexus follows the ICA along the extracranial path, the main exit target is the ophthalmic nerve on the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. The exit of sympathetic fibers from the ICA was observed early along the posterior vertical segment. Furthermore, the sympathetic plexus did not follow redundant ICAs; rather, it followed the abducens nerve and then the ophthalmic nerve to the lateral cavernous wall.

Because of the close relationship between the abducens and sympathetic nerves, Parkinson predicted coexistent clinical syndromes,26 which were later confirmed by other investigators.29,30,31 The frequency of these clinical syndromes may be underreported. However, pathological lesions must be located anterior to the posterior vertical segment and lateral to the horizontal segment to compress the fibers from both nerves.

Carotid–Cavernous Fistulas

CCFs are abnormal communications between the carotid artery and the cavernous sinus.32 The symptoms associated with CCFs depend on the direction of the venous drainage, the site of venous thrombosis, and the rate of blood flow through the shunt.

The ultimate goals of treatment should be obliteration of the fistula and preservation of the ICA. The minimum goals of the procedure are to halt the progression of the patient's inevitable visual deficit and to prevent intracranial complications. The strategy for treatment depends on the extent of the lesion and on the availability of the endovascular or surgical teams.

Endovascular Treatment

Endovascular treatment is now a first-line of treatment for CCFs. Transarterial or transvenous accesses may be possible in individual cases.33,34 Occasionally, ischemic injuries to cranial nerves are reported.35 However, an ischemic injury cannot be clearly attributed to an individual intracavernous vascular branch due to the rich anastomoses of this area. In contrast, compressive injuries to cranial nerves are common complications of various embolization techniques.36,37 A transvenous endovascular technique is usually performed via an inferior petrosal sinus route. However, the proximity of the abducens nerve increases the likelihood of deficits when this route is used.38

For a CCF in the MHT region, the position of the fistula can be predicted. Endovascular treatment can be planned to minimize compressive intracavernous nerve injury. In such cases, the risk to the relatively distant sympathetic fibers is decreased. Through a transarterial approach, a redundant ICA poses less risk to the abducens nerve than a normal ICA. However, the transvenous endovascular trajectory can be difficult to use in the presence of a redundant ICA (mean distance from Dorello's canal: 11.2 ± 1.6 (normal ICA) mm versus 6.7 ± 1.5 (redundant ICA) mm, p < 0.001). Compared with an ICA with a normal curve, navigating a microcatheter through a redundant ICA to the site of a carotid fistula might be more difficult. However, large volumes of the embolic agent may be needed when the curvature is normal because the posterosuperior venous space is larger compared with that associated with a redundant ICA. If a fistula occurs in the ILT region, the likelihood of an intracavernous neural injury may be the same in the presence of both types of ICAs.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment may be required if endovascular treatment fails.39,40 The goal of surgical treatment may be direct vascular surgery or indirect packing. However, given the unsatisfactory results associated with direct surgical procedures, sinus packing is now preferred.41,42 Knowledge of the entry corridors to the cavernous sinus triangles is needed to access pathologies safely in this region.1,43,44 Overpacking in any direction or in any particular corridor should be avoided.39 The anteroinferior and the posterosuperior windows used in this study represent simplifications of the various cavernous triangles.41,45

As described by Parkinson, the posterosuperior window is a primary surgical corridor to the cavernous sinus.46 This window is divergent posteriorly and convergent anteriorly. Variations in the position of the trochlear nerve27 make access through the supra- and infratrochlear spaces possible. Most approaches to lesions involving the MHT require opening this window,47 as in our study. In some cases, however, this window also provides a view of the abducens nerve at Dorello's canal. Being unaware of this nerve risks iatrogenic injury to the abducens nerve. Such risks are slightly lower in the presence of a redundant ICA. However, the MHT can be obstructed by the curvature of a redundant ICA. The ILT can be approached directly from a superior view by retracting the ICA or the cranial nerve to some degree.

Approaching through the anteroinferior window is another option. Typically, however, only the anterior bend of the ICA is visible. This angle of approach does not provide good access to the intracavernous branches without excessive retraction of the cranial nerve. The goal of this procedure is limited to packing venous flow to the orbit. In most cases, this approach cannot be used for direct surgical exploration.

Study Limitations

The properties of living tissue cannot be reproduced in formalin-fixed cadavers. Limitations include the lack of gravity-assisted exposure, elasticity of brain tissue, or drainage of cerebrospinal fluid. Encounters with bleeding, however, are avoided. The amount of silicone injected in the cavernous sinus may cause some anatomical shifting. The injections, however, help clarify the potential intracavernous spaces.

In our study, all data were from normal cavernous sinuses. Pathology such as mass lesions, however, may alter anatomical relationships. Lesions may be clinically silent until enlarging pathological conditions have considerably distorted the cavernous sinus. Cavernous venous spaces can be expanded to enlarge the surgical view, but extra packing or embolization procedures are needed to do so.

Many soft tissue parameters cannot be seen clearly on radiological studies (e.g., the PLL, CN VI, dural rings). Three-dimensional anatomical structures and their relationships relative to each other cannot be measured exactly the same way as routinely done on two-dimensional radiologic films. The distinction between the two types of ICAs remains slightly ambiguous. However, anatomical–radiological correlations that help in understanding the cavernous carotid and neural structures can be simplified, as in our study, with complementary data.

CONCLUSION

The intracavernous curve of the ICA correlates with the kyphotic curvature of the skull, not with age. The curvature of the intracavernous ICA provides some clinical guidelines for localizing intracavernous arterial branches. When an ICA has a normal curvature, its intracavernous branches and intracavernous neural structures are close to each other, especially in the region of the MHT. The opposite is true for ICAs with a redundant curvature. The position of the ILT is unpredictable regardless of the type of ICA. Redundant ICAs are common in skulls with a steep cavernous angle. It might be possible to predict the intraoperative risk of neural compression in the intracavernous region. Complementary surgical and endovascular data can help surgeons access this formidable area and prevent unnecessary complications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr. Bradford Burling, Medtronic, Inc., for providing expert technical assistance on the Stealth Station. We also thank the staff of Neuroscience Publications, Barrow Neurological Institute for their help in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Harris F S, Rhoton A L. Anatomy of the cavernous sinus. A microsurgical study. J Neurosurg. 1976;45(2):169–180. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Rhoton A L, Jr, Theele D, Barry M E. Surgical approaches to the cavernous sinus: a microsurgical study. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):903–932. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase T, Loveren H van, Keller J T, Tew J M. Meningeal architecture of the cavernous sinus: clinical and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(3):527–534. discussion 534–536. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Yamamoto I, Shinozuka S, Sato O. Microsurgical anatomy of the cavernous sinus. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1994;34(3):150–163. doi: 10.2176/nmc.34.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Surgical anatomy of the lateral sellar compartment (cavernous sinus) Clin Neurosurg. 1990;36:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson M W. Neuroanatomy of the cavernous sinus and clinical correlations. Optom Vis Sci. 1990;67(12):891–897. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taptas J N. The so-called cavernous sinus: a review of the controversy and its implications for neurosurgeons. Neurosurgery. 1982;11(5):712–717. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198211000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky F, Nathan H. The lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. With special reference to the nerves related to it. J Neurosurg. 1982;56(2):228–234. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.2.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky F, Valarezo A, Elidan J. The superior wall of the cavernous sinus: a microanatomical study. J Neurosurg. 1994;81(6):914–920. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.6.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolenc V. Direct microsurgical repair of intracavernous vascular lesions. J Neurosurg. 1983;58(6):824–831. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.6.0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveren H R van, Keller J T, el-Kalliny M, Scodary D J, Tew J M., Jr The Dolenc technique for cavernous sinus exploration (cadaveric prosection). Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(5):837–844. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.5.0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg R A, Vakil N, Hong T A, et al. Evaluation of platybasia with MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(1):89–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthillier A, Loveren H R van, Keller J T. Segments of the internal carotid artery: a new classification. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(3):425–432. discussion 432–433. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E. Die Lageabweichungen der vorderen hirnarterie im gefassbild. Zentralbl Neurochir. 1938;3:300–313. [Google Scholar]

- Gibo H, Lenkey C, Rhoton A L., Jr Microsurgical anatomy of the supraclinoid portion of the internal carotid artery. J Neurosurg. 1981;55(4):560–574. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.4.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziyal I M, Ozgen T, Sekhar L N, Ozcan O E, Cekirge S. Proposed classification of segments of the internal carotid artery: anatomical study with angiographical interpretation. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2005;45(4):184–190. discussion 190–191. doi: 10.2176/nmc.45.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrun G, Lacour P, Vinuela F, Fox A, Drake C G, Caron J P. Treatment of 54 traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1981;55(5):678–692. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.5.0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisht A, Barnett D W, Barrow D L, Bonner G. The blood supply of the intracavernous cranial nerves: an anatomic study. Neurosurgery. 1994;34(2):275–279, discussion 279. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Dinh H. Cavernous branches of the internal carotid artery: anatomy and nomenclature. Neurosurgery. 1987;20(2):205–210. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198702000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Collateral circulation of cavernous carotid artery: anatomy. Can J Surg. 1964;7:251–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasjaunias P, Moret J, Doyon D, Vignaud J. C5 collaterals of the internal carotid siphon: embryology, angiographic anatomical correlations, pathological radio-anatomy (author's transl) Neuroradiology. 1978;16:304–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00395282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasjaunias P, Moret J, Mink J. The anatomy of the inferolateral trunk (ILT) of the internal carotid artery. Neuroradiology. 1977;13(4):215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00344216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist E, Willén R. Cavernous nodules in the dural sinuses. An anatomical, angiographic, and morphological investigation. J Neurosurg. 1974;40(3):330–335. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.40.3.0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Lateral sellar compartment: history and anatomy. J Craniofac Surg. 1995;6(1):55–68. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199501000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J A, Parkinson D. Intracranial sympathetic pathways associated with the sixth cranial nerve. J Neurosurg. 1974;40(2):236–243. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.40.2.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Bernard, Mitchell, Horner syndrome and others? Surg Neurol. 1979;11(3):221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeeke J J van, Jansen J J, Tulleken C A. The cavernous sinus syndrome. An anatomical and clinical study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1988;90(4):311–319. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(88)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeeke J J van, Dujovny M, Troost D. Anatomy of the sympathetic pathways in the cavernous sinus. Neurol Res. 1995;17(1):2–8. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1995.11740280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman I, Levartovski S, Goldhammer Y, Tadmor R, Findler G. Sixth nerve palsy and unilateral Horner's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(7):913–916. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M N, Saeki N, Hirai S, Yamaura A. Unusual cranial nerve palsy caused by cavernous sinus aneurysms. Clinical and anatomical considerations reviewed. Surg Neurol. 1999;52(2):143–148. discussion 148–149. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H, Ishikawa H, Asayama K, Saito T, Endo S, Mizutani T. Abducens nerve palsy and Horner syndrome due to metastatic tumor in the cavernous sinus. Intern Med. 2005;44(6):644–646. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow D L, Spector R H, Braun I F, Landman J A, Tindall S C, Tindall G T. Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(2):248–256. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A I, Tomsick T A, Tew J M., Jr Management of 100 consecutive direct carotid-cavernous fistulas: results of treatment with detachable balloons. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(2):239–244. discussion 244–245. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théaudin M, Saint-Maurice J P, Chapot R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dural carotid-cavernous fistulas: a consecutive series of 27 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(2):174–179. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D H, Song J K, Eskridge J M. Embolization of meningohypophyseal and inferolateral branches of the cavernous internal carotid artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(6):1061–1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Miyachi S, Negoro M, et al. Endovascular treatment strategy for direct carotid-cavernous fistulas resulting from rupture of intracavernous carotid aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(9):1789–1796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanke I, Doerfler A, Stolke D, Forsting M. Carotid cavernous fistula due to a ruptured intracavernous aneurysm of the internal carotid artery: treatment with selective endovascular occlusion of the aneurysm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(6):784–787. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozveren M F, Uchida K, Aiso S, Kawase T. Meningovenous structures of the petroclival region: clinical importance for surgery and intravascular surgery. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(4):829–836. discussion 836–837. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200204000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J D, Fukushima T. Direct microsurgery of dural arteriovenous malformation type carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas: indications, technique, and results. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(5):1119–1124. discussion 1124–1126. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199711000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero C A, Raja A I, Naranjo N, Krisht A F. Obliteration of carotid-cavernous fistulas using direct surgical and coil-assisted embolization: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(2):E382, discussion E382. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000199345.43514.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan S. In: Apuzzo MLJ, editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. Fistulas and vascular malformations of the dura and dural sinuses. pp. 1117–1141.

- Tu Y K, Liu H M, Hu S C. Direct surgery of carotid cavernous fistulae and dural arteriovenous malformations of the cavernous sinus. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(4):798–805. discussion 805–806. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima T, Day J. Intracavernous carotid artery aneurysms. Brain Surger: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill; 1993. pp. 925–944.

- Hakuba A, Tanaka K, Suzuki T, Nishimura S. A combined orbitozygomatic infratemporal epidural and subdural approach for lesions involving the entire cavernous sinus. J Neurosurg. 1989;71(5 Pt 1):699–704. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.5.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour M, Wallace M. Surgical management of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Schmidek and Sweet's Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006. pp. 1287–1305.

- Parkinson D. A surgical approach to the cavernous portion of the carotid artery. Anatomical studies and case report. J Neurosurg. 1965;23(5):474–483. doi: 10.3171/jns.1965.23.5.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolenc V V. Surgery of vascular lesions of the cavernous sinus. Clin Neurosurg. 1990;36:240–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]