ABSTRACT

Postoperative temporalis muscle atrophy from injury to the neurovascular supply can cause significant cosmetic disfigurement, and avoidance of electrocautery use has become a common practice in minimizing this outcome. We attempted to quantify the effects of electrocautery on temporalis atrophy by retrospectively reviewing postoperative magnetic resonance images in patients having undergone an orbital frontal craniotomy. We reviewed medical records and compared volumetric measurements of the temporalis muscle in 25 patients using the contralateral temporalis muscle as an internal control. The mean size of the nonsurgical temporalis muscle was 24.6 cm3 as compared with 23.6 cm3 on the operated side. The difference of 1.0 cm3 was not statistically significant (p = 0.32). The only postoperative atrophy noted visually on the magnetic resonance images developed in the posterior superior aspect of the temporalis muscle, behind the vertical incision of the temporalis muscle. In the small control group, with known injury to V3, the mean nonsurgical size was 27.7 cm3, whereas it was 16.5 cm3 on the contralateral surgical side. The difference of 11.2 cm3 was statistically significant (p = 0.04). These findings suggest that the use of electrocautery to dissect the temporalis muscle does not significantly contribute to atrophy provided careful surgical technique is practiced.

Keywords: Temporalis muscle, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), atrophy, electrocoagulation, craniotomy

Temporalis muscle atrophy can be a commonly encountered complication plaguing neurosurgeons after successful craniotomies.1,2 Furthermore, the extent of atrophy can be augmented with the use of skull base approaches, such as orbitofrontal or orbitozygomatic craniotomies, as more muscle is dissected from its attachment to the calvarium. The temporalis muscle can sustain injury leading to atrophy by denervation of the muscle, damage to its vascular supply, or direct muscle fiber injury.2,3,4

A high incidence of temporal hollowing and cosmetic dissatisfaction among patients led to several varying proposed methods of muscle preservation. Surgical techniques developed to minimize such injuries include decreased retraction time of the muscle, techniques to better reapproximate the muscle, minimized transection of the muscle, bone flaps, osteotomies, or use of screws to reapproximate the muscle, and a greater component of the muscle being allowed to be attached to the calvarium.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 However, the most universally adopted technique is avoidance of electrocautery use when dissecting the muscle to preserve the neurovascular supply and dissecting the muscle in a retrograde fashion with a periosteal elevator, from the skull above the zygoma up toward the muscle attachment. Oikawa et al2 reported this technique and good cosmetic outcomes in 100 patients.

However, we have routinely used careful electrocautery when dissecting the temporalis muscle from the calvarium to minimize bleeding during the exposure. We have not noted cosmetic disfigurement among patients with careful electrocautery use and attempted to quantitatively compare the amount of temporalis muscle atrophy with our application of electrocautery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained through our local committee to retrospectively review medical records and radiographs of patients treated by the primary surgeon (C.B.H.). We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who had undergone orbitofrontal or orbitozygomatic approaches to skull base lesions from 2005 to 2008. Initially, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements were collected, but too few patients had available imaging because most patients had images initially obtained at other institutions. Patients were excluded if they only had postoperative imaging less than 4 weeks after surgery or if insufficient records or radiographs were available.

After excluding patients who did not fulfill criteria, 25 patients remained with sufficient data. Three patients were used as a control group. One of these patients had preresection embolization of a large sphenoid wing meningioma. Another patient had preoperative V3 dysfunction with atrophy of the temporalis and masseter, and the remaining patient had surgical sacrifice of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve to aggressively resect a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST). Given the known injury to the neurovascular supply of the muscle or preexisting injury, these cases were used as a control group to gauge the severity of muscle atrophy with significant injury. The remaining 22 patients comprised the principle study cohort.

All medical records were reviewed for demographic data, side of surgery, type of craniotomy (orbitofrontal or orbitozygomatic), time interval between surgery and radiographic follow-up, clinical and neurologic presentation, complications, new postoperative neurologic deficits, and pathology.

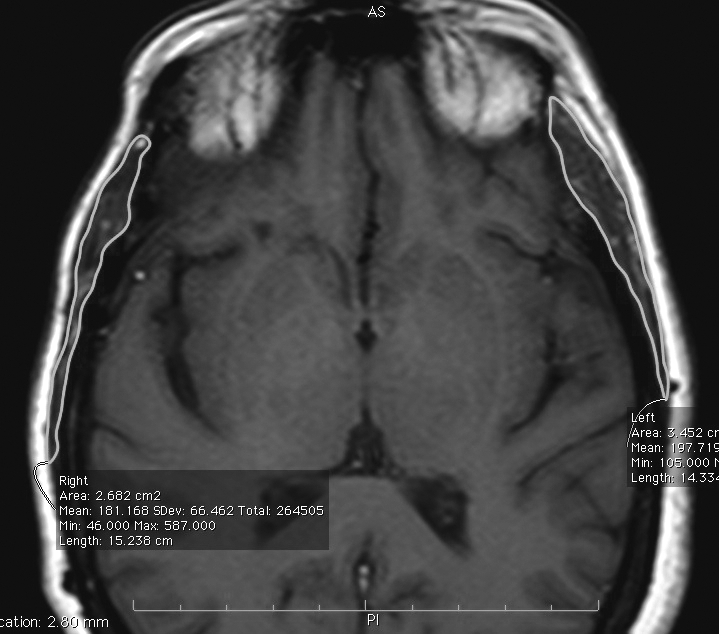

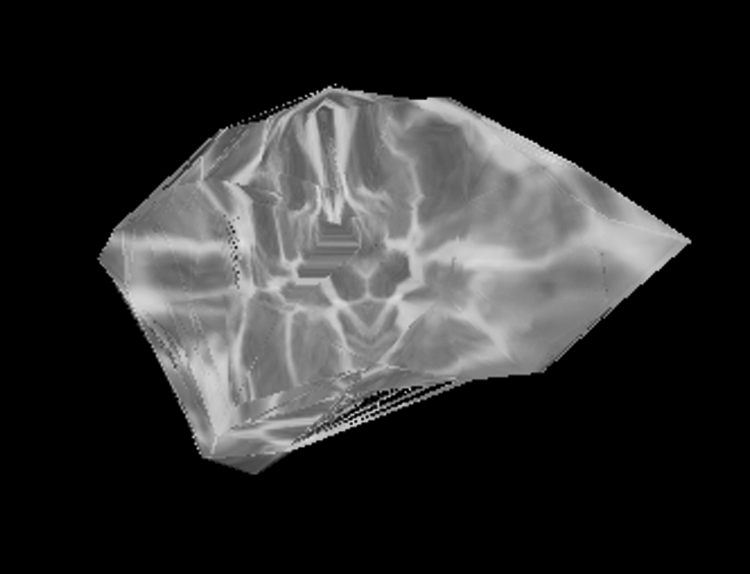

Postoperative MRI images were reviewed using OsiriX imaging software. Serial image measurements were calculated to approximate the volumetric mass of the temporalis muscle. To create a three-dimensional volumetric mass reconstruction of the temporalis muscle in each patient, a region of interest (ROI) was drawn to outline the temporalis muscle on each two-dimensional slice of the series (Fig. 1). The individual ROIs were then grouped and locked as a single ROI to properly segment the left and right temporalis muscle. Finally, OsiriX used its automated measurement of each two-dimensional area outlined to create a three-dimensional volume per series (Fig. 2). The area calculated by OsiriX was extended to the seventh decimal place, and the volume was calculated using a Delaunay reconstruction filter. Two co-authors reviewed the measurements using T1 axial images in most cases. In a few patients, gadolinium-enhanced images were selected because of improved image quality. In three patients, volumetric measurements were based on T2-weighted imaging. The sequence chosen generally was that with the least motion artifact and the best image quality.

Figure 1.

Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing an example of temporalis measurements. The temporalis muscle is delineated in the region of interest (ROI) by the green line.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional volumetric calculation of temporalis mass based on demarcated regions of interest (ROIs).

A paired Student t test was used to compare the degree of atrophy from the side of the nonoperated temporalis muscle against the postsurgical temporalis. Differences were considered significant if the p value was <0.05.

Our surgical technique largely replicates standard described approaches for orbitofrontal or orbitozygomatic exposures. We favor a more posterior vertical muscle incision transecting through the temporalis muscle to minimize the volume of denervated muscle posterior to that incision. In all cases, a small cuff of temporalis was left attached at the superior temporal line to reapproximate the muscle as described by Spetzler and Lee.4 Gentle countertraction of the muscle is used when using the monopolar cautery flush against the calvarium to detach the temporalis muscle. If this is done properly, the electrocautery tip is moved side to side, elevating and preserving the thin periosteal layer up with the muscle, while avoiding pushing the electrocautery tip into the muscle fibers. If bleeding starts within the muscle itself, hemostasis is obtained with focal use of bipolar cautery. We routinely plate a segment of mesh to cover the craniotomy defect near McCarty's point and usually place hydroxyapatite bone cement to seal any bony gap to minimize a temporal hollowing effect.

RESULTS

Our primary sample consisted of 22 patients with a mean age of 52.9 years (range 6.9 to 86.1, median 55.1 ± 21.2). Visual complaints were the most common in 18 patients, but none in this group had preexisting trigeminal nerve dysfunction. Eight patients were female and 11 had left-sided craniotomies. Three patients underwent orbitozygomatic approaches and the remaining 19 had orbitofrontal craniotomies. Mean imaging follow-up was obtained 9 months after surgery in this cohort (range 1.13 to 23.97 months, median 9 ± 6). Table 1 summarizes the remaining demographic information.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic Data

| Characteristic | Control Group | Study Group |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3 | 22 |

| Mean age [range] (years) | 45.7 [28.7–62.3] | 52.9 [6.9–86.2] |

| Gender, F:M | 2:1 | 14:8 |

| Side of surgery, R:L | 1:2 | 11:11 |

| Number of orbitofrontal | 1 | 19 |

| Number of orbitozygomatic | 2 | 3 |

| Mean interval MRI follow-up (months) | 12 [1.13–28.2] | 9 [1.13–23.97] |

In our three control patients, the mean age was 45.7 years (28.7 to 62.3) with two female patients. These patients were selected as control patients because of known injury to the neurovascular supply or preexisting atrophy of the muscle. They had mean radiographic follow-up 12 months postoperatively (range 1.13 to 28.2 months, median 7.6 months). Pathologic subtypes included 10 skull base meningiomas, 1 cavernous sinus hemangioma, 3 pituitary adenomas with extension into the cavernous sinus, 2 craniopharyngiomas, 1 schwannoma, 1 arteriovenous fistula, 1 glomus tumor, 1 MPNST, 1 neuroepithelial cyst, and 1 suprasellar xanthogranuloma. The control group included a meningioma, an MPNST, and a schwannoma. Each group had a postoperative CSF leak, but otherwise no new permanent neurologic deficits were encountered.

In the study cohort, the mean size of the unoperated temporalis muscle was 24.6 cm3 (median 25.6 ± 9.3 cm3). The contralateral temporalis in these patients had a mean volume of 23.6 cm3 (median 22.6 ± 9.4 cm3) leaving a difference between the means of 1.0 cm3 (p = 0.32, 95% CI −3.13 to 1.09). In our control group, the mean size of the nonsurgical temporalis muscle was 27.7 cm3 as compared with 16.5 cm3 on the contralateral muscle. The difference of 11.2 cm3 was statistically significant in this small sample (p = 0.04, 95% CI −21.27 to −1.14). The results are summarized in Table 2. The remaining variables of age, gender, procedure type, and side of surgery were tested and did not have a significant impact on the volume of the temporalis muscle.

Table 2.

Summary of Results between both Groups

| Mean Temporalis Mass of Surgical Side (cm3) | Mean Temporalis Mass of Nonoperated Side (cm3) | Mean Difference (cm3) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 3) | 16.5 | 27.7 | 11.2 | 0.04 |

| Embolized (n= 1) | 14.2 | 26.2 | 12.0 | |

| Preop deficit (n = 1) | 25.8 | 32.6 | 6.8 | |

| Sacrificed V3 (n = 1) | 9.6 | 24.4 | 14.8 | |

| Study group (n = 22) | 23.6 | 24.6 | 1.0 | 0.32 |

DISCUSSION

As surgical outcomes improve, increasing focus is placed on alternate measures of success. One of these was the unacceptably common development of temporalis muscle atrophy and hollowing of the temporal area. Although many surgical techniques have been proposed to minimize muscle atrophy, the most often referenced and generally applied modification was published by Oikawa et al.2 They reported cosmetically satisfactory outcomes in 100 patients by avoiding use of electrocautery and dissecting the temporalis in a retrograde fashion, from the zygoma upward under the muscle belly.

Although the anatomy of the neurovascular supply to the temporalis muscle has been well described,3 we hypothesized that the risk of injury was not primarily from use of electrocautery, but mainly from application of surgical technique. We routinely use electrocautery when dissecting the temporalis muscle to minimize bleeding by carefully applying traction to the muscle and using the flat electrocautery blade flush against the calvarium to liberate the muscle from its origin down to ∼1 cm from the infratemporal crest. Electrocautery is used over the entire temporalis fossa, but as we dissect to within 1 cm of the infratemporal crest, we switch to sharp periosteal elevators where the nerve supply of the temporalis muscle is exposed on the deep side of the muscle. Care is taken to avoid moving the electrocautery into the muscle fibers at all times. If muscle bleeding occurs, it is controlled with fine tip bipolar cautery. Our radiographic measurements suggest that no significant difference develops with careful use of electrocautery (p = 0.32). The mean difference between both sides was 1 cm3 as compared with a difference of 11.2 cm3 when known injury of the neurovascular supply was present. The slight difference noted in the surgical cohort was likely due to atrophy of the temporalis muscle over the posterior temporal–parietal muscle belly, the component behind the vertical incision made in the muscle allowing for inferolateral retraction. Clinical records also corroborated that the control patients had noticeable asymmetry of the temporalis on physical assessment. Unfortunately, on retrospectively collecting the data, insufficient information was available in the charts to compare patient cosmetic satisfaction.

Although several authors have assessed the cadaveric anatomy of the temporalis muscle3 and others have attempted to assess clinical measures of cosmesis,1,2,8 none have attempted to measure the volumetric size of the temporalis. de Andrade et al1 compared two surgical techniques and evaluated for asymmetry of the temporalis muscle by measuring a bitemporal diameter. However, this technique only assesses one point of the muscle and is prone to greater error if the muscle is attached imperfectly. Others have highlighted the importance of proper temporalis muscle reattachment.12

Park and Hamm9 attempted to quantify the temporal hollowing by measuring the thickness of the muscle, but again this reflects only a single two-dimensional measure and may be predisposed to error based on the temporalis reattachment. Moreover, the temporalis may fibrose into a craniotomy defect and falsely diminish the perceived thickness of the muscle. Our volumetric measures reflect the entire temporalis muscle and hence may be more sensitive to detecting variations. Additionally, our comparison minimizes error in measurements arising from temporalis reapproximation as the entire muscle mass is recorded.

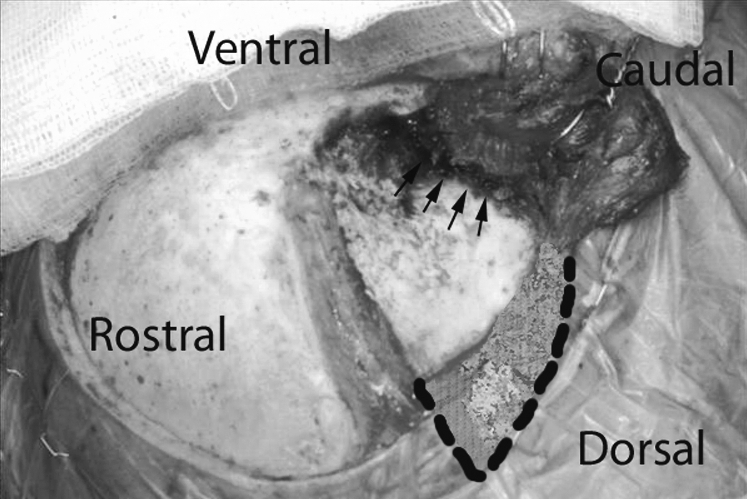

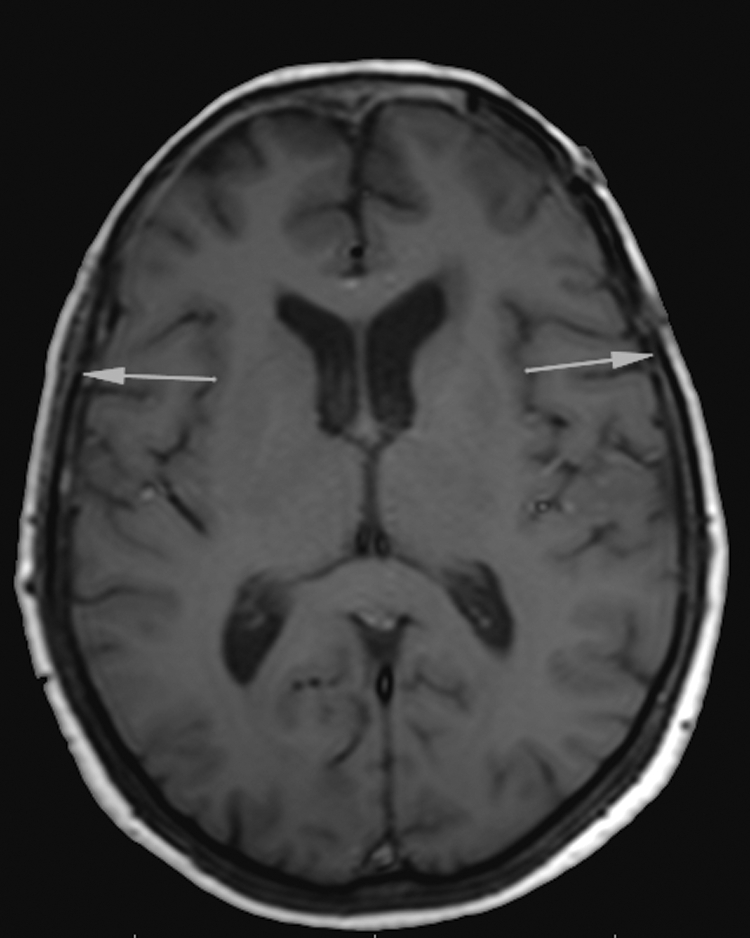

We noted that the majority of atrophy appeared to develop more posteriorly along the temporalis (Figs. 3 and 4). This may reflect that atrophy develops mostly in the posterior component of the temporalis that is transected from its neurovascular supply, not necessarily from use of electrocautery. Therefore, the dissection of the temporalis muscle should start as posterior as the skin incision permits to minimize the amount of atrophy. Such atrophy posteriorly should also have a minimal effect on cosmesis and not affect the temporal hollowing typically visualized.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative image displaying the vertical transection of the temporalis muscle to permit inferolateral retraction of the muscle. The highlighted area depicts the posterior margin of the temporalis where the majority of atrophy was observed. Arrows identify the area of greatest risk to injury of the neurovascular supply and where limited electrocautery use may be warranted.

Figure 4.

Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) highlighting the asymmetric atrophy of the temporalis muscle component posterior to the vertical transection. Arrows highlight the smaller posterior component of the temporalis on the operated left side as compared with the control right side.

Other techniques that have been previously reported to minimize cosmetic asymmetry include filling the craniotomy defect with bone chips, hydroxyapatite, or titanium mesh, carefully reattaching the muscle, minimizing transection of the muscle, sharply dissecting in a retrograde fashion, and using various bone flaps, osteotomies, or microscrews as attachment points.1,2,4,5,6,8,10,11,12 Certainly, any or all of these may play a role in minimizing temporalis atrophy. However, based on MRI volumetric analysis, it appears that the use of electrocautery does not contribute significantly to muscle atrophy provided careful technique is adopted.

REFERENCES

- de Andrade Júnior F C, de Andrade F C, de Araujo Filho C M, Carcagnolo Filho J. Dysfunction of the temporalis muscle after pterional craniotomy for intracranial aneurysms. Comparative, prospective and randomized study of one flap versus two flaps dieresis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1998;56:200–205. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1998000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa S, Mizuno M, Muraoka S, Kobayashi S. Retrograde dissection of the temporalis muscle preventing muscle atrophy for pterional craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:297–299. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.2.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadri P AS, Al-Mefty O. The anatomical basis for surgical preservation of temporal muscle. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:517–522. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.3.0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler R F, Lee K S. Reconstruction of the temporalis muscle for the pterional craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:636–637. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.4.0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles A P., Jr Reconstruction of the temporalis muscle for pterional and cranio-orbital craniotomies. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:524–529. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunori A, DiBenedetto A, Chiappetta F. Transosseous reconstruction of temporalis muscle for pterional craniotomy: technical note. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1997;40:22–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusimano M D, Suhardja A S. Craniotomy revisited: techniques for improved access and reconstruction. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27:44–48. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100051969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N, Hirashima Y, Kurimoto M, Asahi T, Tomita T, Endo S. One-piece pedunculated frontotemporal orbitozygomatic craniotomy by creation of a subperiosteal tunnel beneath the temporal muscle: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1520–1523, discussion 1523–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Hamm I S. Cortical osteotomy technique for mobilizing the temporal muscle in pterional craniotomies. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:174–178. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.1.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeno T, Tanaka J, Atsuchi M. Orbitozygomatic approach by transposition of temporalis muscle and one-piece osteotomy. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:81–83. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabramski J M, Kiriş T, Sankhla S K, Cabiol J, Spetzler R F. Orbitozygomatic craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:336–341. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.2.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager E L, DelVecchio D A, Bartlett S P. Temporal muscle microfixation in pterional craniotomies. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:946–947. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.6.0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]