Abstract

Geniculate ganglion (GG) cell bodies of chorda tympani (CT), greater superficial petrosal (GSP), and posterior auricular (PA) nerves transmit orofacial sensory information to the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract (rNST). We used whole cell recording to study the characteristics of the Ca2+ channels in isolated Fluorogold-labeled GG neurons that innervate different peripheral receptive fields. PA neurons were significantly larger than CT and GSP neurons, and CT neurons could be further subdivided based on soma diameter. Although all GG neurons possess both low voltage–activated (LVA) “T-type” and high voltage–activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents, CT, GSP, and PA neurons have distinctly different Ca2+ current expression patterns. Of GG neurons that express T-type currents, the CT and GSP neurons had moderate and PA neurons had larger amplitude T-type currents. HVA Ca2+ currents in the GG neurons were separated into several groups using specific Ca2+ channel blockers. Sequential applications of L, N, and P/Q-type channel antagonists inhibited portions of Ca2+ current in all CT, GSP, and PA neurons to a different extent in each neuron group. No difference was observed in the percentage of L- and N-type Ca2+ currents reduced by the antagonists in CT, GSP, and PA neurons. Action potentials in GG neurons are followed by a Ca2+ current initiated afterdepolarization (ADP) that may influence intrinsic firing patterns. These results show that based on Ca2+ channel expression the GG contains a heterogeneous population of sensory neurons possibly related to the type of sensory information they relay to the rNST.

INTRODUCTION

Cell bodies of afferent fibers of the chorda tympani (CT), greater superficial petrosal (GSP), and posterior auricular nerves (PA) are contained in the geniculate ganglion (GG). These nerves relay chemosensory, thermal, and mechanosensitive information from the anterior two thirds of the tongue (CT), soft palate and nasoincior duct (GSP), and the skin surrounding the pinna of the ear (PA) (Brodal 1981). The central process of the ganglion—the nervus intermedius—enters the lateral brain stem and contributes to the solitary tract (May and Hill 2006). Collateral branches of the solitary tract make monosynaptic contact with second-order neurons of the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract via glutamatergic synapses (Li and Smith 1997; Wang and Bradley 1995, 2010; Whitehead and Frank 1983).

The few anatomical studies of GG neurons reported that the CT and GSP cell soma have a typical pseudounipolar morphology (Grigaliunas et al. 2002; Kitamura et al. 1982) and are 15–25 μm in diameter. The PA neuron somata are larger than the CT and GSP neurons (Gomez 1978; Semba et al. 1984). A few larger neurons ranging from 30 to 40 μm in diameter are also reported in the GG (Gomez 1978). In ultrastructural studies of guinea pig, monkey, and human GG, the neurons are described as being similar to those in other sensory ganglia (Lieberman 1976) and are classified as either light or dark cells based on their appearance in electron micrographs (Kitamura et al. 1982; Nawar et al. 1980).

Most research on GG neuron function has involved extracellular recordings of responses to tongue stimulation with chemicals (Boudreau et al. 1983, 1985; Breza et al. 2006; Lundy and Contreras 1999; Sollars and Hill 2005). Intracellular in vitro recordings of isolated GG ganglion cells have been used to characterize their biophysical properties. CT, GSP, and PA neurons were found to have similar passive membrane properties (King and Bradley 2000; Koga and Bradley 2000). However, there were significant differences in cell excitability between the three groups based on action potential threshold current magnitudes, and PA neurons often responded with a burst of action potentials when depolarized. All action potentials of GG neurons were “sharp” with rapid rise and fall times (King and Bradley 2000; Koga and Bradley 2000). The “broad spikes” with a deflection on the repolarizing phase of the action potential described in dorsal root and trigeminal ganglion neurons were not observed in the GG (Grigaliunas et al. 2002; Koerber and Mendell 1992). Isolated GG neurons responded to glutamate receptor agonists (King and Bradley 2000) and substance P and GABA (Koga and Bradley 2000). In immunocytochemical study, GG neurons expressed several glutamate receptor subunits (Caicedo et al. 2004) and subpopulations of GG neurons are positive for ATP receptors (P2X2 and P2X3). Most GG neurons stain positive for TrkB neurotrophin receptors and BDNF is required for GG neuron survival (Matsumoto et al. 2001; Ohmoto et al. 2008; Patel and Krimm 2010).

It is apparent therefore that, despite the importance of the GG in a number of orofacial sensory functions, its basic neurobiological properties have received relatively little attention compared with other sensory ganglia. For example, heterogeneity of GG sensory neurons, a characteristic of other sensory ganglia (Lawson 2002; McMahon and Priestley 2005) has never been fully explored. Unlike other sensory ganglia, no information is available on the relationship between GG neuron size and peripheral fiber size and expression of different neuroproteins. Neurons in other ganglia also differ in their ion channels distribution possibly related to the different sensory modalities they transmit (Kim and Chung 1999). More specifically, multiple types of Ca2+ channel have been described in all sensory ganglion cells studied thus far (Bean 1989; Mendelowitz and Kunze 1992; Miller 1987; Sher et al. 1991; Swandulla et al. 1991). Importantly, these channels are involved in intracellular calcium-dependent processes, can influence the properties of the action potential, play a role in the pattern of action potential discharge, and are necessary for the release of neurotransmitters from the central synapses (Miller 1988).

To date, there is no information on the distribution of different Ca2+ channels in different populations of GG neurons and how these channels influence action potential discharge properties. Based on anatomy and central tracing studies, GG neurons are heterogeneous, relaying different modalities and qualities of sensory information to the sensory relay nuclei in the brain stem and may therefore express a diversity of Ca2+ channels. We used whole cell recordings of GG neurons innervating diverse orofacial receptive fields to characterize the Ca2+ currents based on voltage-dependent activation kinetics and sensitivity to Ca2+ channel antagonists.

METHODS

Fluorescent labeling

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) aged 28–37 days were used in this study. All surgical procedures were carried out under National Institutes of Health and University of Michigan Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols. The ganglion cell labeling technique is based on methods developed in earlier studies (King and Bradley 2000; Koga and Bradley 2000). Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (16 mg/kg). The lower jaw was retracted and the tongue depressed. Under a dissecting microscope, 10 μl of a 3–5% aqueous solution of Fluorogold (Fluorochrome) was injected bilaterally into the anterior tongue or soft palate from a Hamilton microsyringe. To label a strictly mechanoreceptive subpopulation of GG neurons innervated by the posterior auricular branch of the facial nerve, 5 μl of the Fluorogold solution was injected bilaterally just below skin of the ventral external auditory meatus and concha. The rats were allowed to recover on a heating pad until ambulatory.

Dissection and neuronal dissociation

Acutely dissociated GG neurons were prepared as described previously (King and Bradley 2000; Koga and Bradley 2000). Three to 12 days after fluorescent labeling, the rats were reanesthetized with halothane and decapitated, and the head was secured in a stereotaxic bite bar. After removal of the superior skull, the forebrain was removed just rostral to the brain stem. The facial nerves were visualized at their exit from the brain stem, and the petrous portion of the temporal bones was removed to expose the GG. Both left and right ganglia were collected and placed in oxygenated HEPES buffer containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 10 sodium succinate, 15 dextrose, 15 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The ganglia were transferred to HEPES buffer containing 1.5 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma) and 2.5 mg/ml collagenase (type IA, Sigma) and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. After incubation, ganglia were washed three times with HEPES buffer at room temperature. The ganglia were triturated with a series of progressively decreasing diameter, fire-polished Pasteur pipettes to produce a suspension of dissociated neurons. The resulting suspension was placed in a 35-mm-diam petri dish containing poly-d-lysine/laminin–precoated coverslips and kept for ≥30 min before making electrophysiological recordings.

Whole cell patch-clamp recording

The petri dish containing dissociated neurons was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (ECLIPSE TE300, Nikon) equipped with epifluorescence and phase contrast optics. The cell suspension was continuously perfused at about 2 ml/min with HEPES buffer at room temperature. Recordings were performed between 30 min and 7 h after plating. Fluorogold-labeled GG neurons were identified by brief exposure to ultraviolet light. Patch electrodes were pulled using a two-stage puller (Narishige PP-83 puller) from borosilicate filament glass (1.5 OD, World Precision Instruments). Electrode tip resistance was between 1.5 and 2.5 MΩ when filled with internal solution.

Electrodes were positioned under visual control onto the membrane of neurons using a hydraulic three-axis micromanipulator (Narishige). A gigaohm seal between the electrode and neuron was established in a HEPES buffer. Neurons were recorded in the standard whole cell patch-clamp configuration with an Axopatch 1D amplifer (Axon Instruments) for voltage-clamp experiments or an Axoclamp 2A amplifer (Axon Instruments) in bridge mode for current-clamp recordings. Current- and voltage-clamp protocols, data acquisition, and analysis were performed using pCLAMP 8 software (Axon Instruments). Signals were low-pass filtered at 2-kHz, digitized at 20–50 kHz (DigiData 1200, Axon Instruments), and stored on a computer. For voltage-clamp recordings, series resistance and cell membrane capacitance were electronically compensated. Leak subtraction was performed with an on-line P/4 or P/5 protocol using pCLAMP software. Measurements of cell capacitance were calculated by fitting a single exponential curve to the uncompensated current trace from a voltage step from −60 to −70 mV. For current-clamp experiments, bridge balance was carefully monitored throughout the experiments and adjusted when necessary. Recordings were made at room temperature.

For voltage-clamp experiments, the external solution used to isolate Ca2+ currents contained (in mM) 140 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 2 MgCl2, 3 CaCl2, 10 dextrose, and 10 HEPES adjusted to pH 7.4 with TEA-OH. HEPES buffer served as the external solution for current-clamp recordings. In some experiments, extracellular Ca2+ concentration was raised from 2 to 6 mM. The internal solution used for voltage-clamp experiments contained (in mM) 120 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 Na-GTP (pH 7.3 adjusted with CsOH). The internal solution for current-clamp recordings contained (in mM) 130 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, and 2 Mg-ATP buffered to pH 7.3 with KOH. The liquid junction potential of the internal solution used for current-clamp experiments (10 mV) was subtracted from the membrane potential values. The liquid junction potential for internal solution used for voltage-clamp experiments was not compensated.

Drug application

Stock solutions of the Ca2+ channel antagonists ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTX: 100 μM; Alomone Labs), ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-Aga IVA: 20 μM; Tocris Bioscience), CdCl2 (Cd2+: 10 mM; Sigma), and NiCl2 (Ni2+: 20 mM; Sigma) were dissolved in distilled H2O, and ω-CgTX and ω-Aga IVA were kept in frozen aliquots. Stock solution of nimodipine (Sigma) was prepared by dissolving in 100% ethanol at concentrations of 0.5 mM. All experiments using nimodipine were carried out in the dark to avoid photosensitive degradation. Antagonist stock solutions (2.5 μl) were pipetted near the cell body after the HEPES buffer flow was stopped, achieving a final concentration indicated in the text. All antagonists were tested on the same neuron. We have applied subsequent calcium channel antagonist to the GG neurons once relatively stable current amplitude was observed in the presence of last antagonist (Baccei and Kocsis 2000; Scroggs and Fox 1991). The blocking effects of high voltage–activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents by antagonists took into consideration rundown of current amplitudes (Scroggs and Fox 1992). After the current amplitude was relatively stable, the rate of rundown before drug application was calculated, and this rate was used for correction of the drug effects to indicate the approximate extent of current rundown during drug application.

Data analysis

Electrophysiological data were analyzed using Clampfit 8 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 6.1 software (Originlab). The amplitude of the Ca2+ current at each test potential for current-voltage (I-V) plots was measured as the difference between the peak and the baseline values. The amplitude of the low voltage–activated (LVA) T-type Ca2+ current was calculated from the peak subtracted from the current at the end of the test potential to avoid small contamination with residual HVA currents. The HVA Ca2+ current amplitude was obtained from the peak value to baseline of the current. The peak conductance (G) at each potential was calculated from the corresponding peak current using the equation G = I/(E − Erev), where Erev is the reversal potential measured for each cell, I is the peak current amplitude, and E is the membrane potential. Normalized peak conductance (G/Gmax) during the activation and the peak current amplitude during the steady-state inactivation (I/Imax) were fitted using a Boltzmann function of the following form: G/Gmax or I/Imax = 1 + exp(V50 − V)/k, where Gmax is the maximal conductance and Imax is the maximal amplitude of the Ca2+ current, V50 is the membrane potential for 50% of Ca2+ current activation and inactivation, and k is the voltage-dependent slope factor. Average soma diameter was calculated from the mean of the longest and shortest axes of the neuron measured with an eyepiece micrometer. No changes in cell size were observed during recording.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the PASW statistics program (SPSS). Data are expressed as mean ± SE, and statistical significances (P < 0.05) between groups were assessed using Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA, which was followed by Scheffe's post hoc tests for comparison of values and χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for comparison of proportion.

RESULTS

Identification of neurons labeled with Fluorogold

Recordings were made from neurons that project to the anterior tongue via the chorda tympani (CT neurons, n = 76); the soft palate via the greater superficial petrosal nerve (GSP neurons, n = 61); and the inner surface of the ear via the posterior auricular branch of the facial nerve (PA neurons, n = 55). The Fluorogold-labeled neurons were easily identified under ultraviolet illumination and were spherical or ovoid in shape, with a diameter between 22 and 32.5 μm. Some of neurons had short processes and became loosely attached to the bottom of the dish. The average diameters of the CT, GSP, and PA neurons were 27.6 ± 0.3, 27.2 ± 0.3, and 29.3 ± 0.2 μm, respectively. PA neurons were significantly larger than CT and GSP neurons (P < 0.01). Once a labeled neuron was identified, whole cell recordings were performed under brightfield illumination.

Whole cell Ca2+ currents of GG neurons

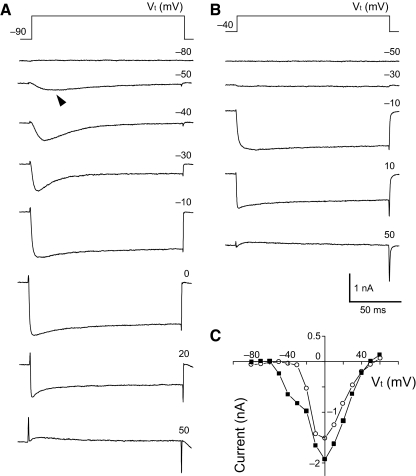

Ca2+ currents were recorded under conditions that suppressed K+ and Na+ by the replacements of internal KCl with CsCl and external NaCl with TEA-Cl, respectively (see methods). Figure 1 shows whole cell Ca2+ current from a GSP neuron activated by 150-ms depolarizing step pulses from a holding potential of either −90 or −40 mV to test potentials from −80 to 60 mV in 10-mV increments. A fast transient inactivating current component was first observed at a test potential of −50 mV from a holding potential of –90 mV (filled arrowhead in Fig. 1A) and followed by more slowly inactivating component at more positive test potentials. In this study, a noninactivating low-threshold current, which was sensitive to nimodipine, L-type channel antagonist (Durante et al. 2004; Kline et al. 2009), was not observed from a holding potential of −90 mV to test potentials of −50 or −40 mV, further supported by the data that application of 5 μM nimodipine did not affect the currents activated at test potentials of either −50 or −40 mV in the CT (n = 7), GSP (n = 6), and PA neurons (n = 6). From a holding potential of −40 mV, transient inactivating components could no longer be evoked over the whole range of test potentials, but a sustained, slowly inactivating component was apparent (Fig. 1B). A plot of the I-V relationship of the peak currents at two different holding potentials (Fig. 1C) indicates two GG neuron current components with different activation ranges: LVA T-type and HVA Ca2+ currents.

Fig. 1.

Whole cell Ca2+ currents in a geniculate ganglion (GG) neuron. A: example of current traces in a greater superficial petrosal (GSP) neuron activated by depolarizing step pulses (150 ms) from a holding potential of –90 mV to test potentials (Vt) from −80 to 60 mV as shown at the top right in each trace. A fast decaying component of current was observed first at a Vt of −50 mV (arrowhead). B: current traces elicited from a holding potential of −40 mV as shown at the top right in each trace. Note the disappearance of transient inactivating components shown in A. Current traces in A and B were obtained from the same neuron. C: I–V relationship obtained from the current traces shown in A and B.

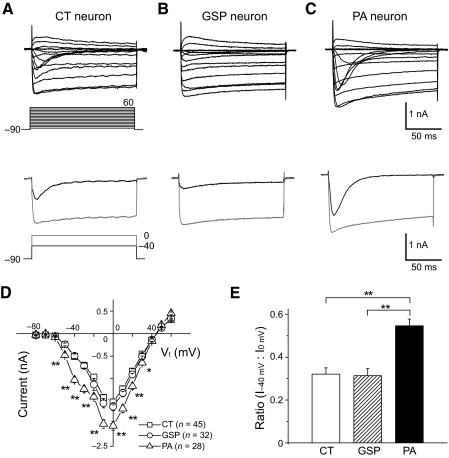

To determine the characteristics of Ca2+ currents in different subpopulations of GG neurons, we evoked Ca2+ current in CT (n = 45), GSP (n = 32), and PA neurons (n = 28). The inward Ca2+ currents were typically activated at a test potential of around −50 mV and reached the maximum at 0 mV in CT, GSP, and PA neurons (Figs. 2, A–C). CT and GSP neurons had moderate transient T-type Ca2+ currents at hyperpolarized test potentials of about −40 mV and large sustained HVA Ca2+ currents at more depolarized test potentials (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, PA neurons expressed relatively large T-type Ca2+ currents at hyperpolarized potentials of around −40 mV compared with HVA Ca2+ currents evoked by larger depolarizing test potentials (Fig. 2C). This resulted in a prominent shoulder at negative test potentials of the I-V relationship in PA neurons (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Whole cell Ca2+ currents in different subpopulations of GG neurons. A–C: families of Ca2+ currents evoked in representative chorda tympani (CT) (A), GSP (B), and posterior auricular (PA) (C) neurons by depolarizing steps from a holding potential of −90 mV to test potentials from −80 to 60 mV in 10 mV increments (top) and the representative current traces evoked from a holding potential of −90 mV to test potentials of −40 and 0 mV (bottom). Current traces in the bottom were obtained from the same neurons as in the top. Voltage protocols used to activate Ca2+ currents in A–C are shown below the current traces in column A. Note that CT and GSP neurons had small T-type Ca2+ currents and large high voltage–activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents, whereas PA neurons had large T-type Ca2+ currents and equally prominent HVA Ca2+ currents. D: average I-V curve obtained from CT, GSP, and PA neurons. The I-V curve for PA neurons displays a prominent shoulder at hyperpolarized test potentials. All points are the mean values from 45 CT, 32 GSP, and 28 PA neurons, respectively. E: histogram of the average ratio of currents at a test potential of −40 mV (I−40 mV) to currents at a test potential of 0 mV (I0 mV) for CT, GSP, and PA neurons (n = 45, 32, and 28 neurons, respectively). The ratio of T-type Ca2+ current to total Ca2+ current was significantly higher in PA neurons than in CT and GSP neurons (P < 0.01). In this and subsequent figures, error bars indicate mean ± SE and significant differences are marked by *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01.

We calculated the current ratio of the Ca2+ current evoked at a test potential of −40 mV to the current evoked at a test potential of 0 mV in CT, GSP, and PA neurons (Fig. 2E). The mean current ratio of PA neurons (0.55 ± 0.03) was significantly higher than that of CT (0.32 ± 0.03) and GSP neurons (0.31 ± 0.03), reflecting a larger contribution of T-type Ca2+ current to total Ca2+ current in PA neurons than in CT and GSP neurons. The I-V curves indicated a significant enhancement of Ca2+ current at test potentials from −50 to 30 mV in PA neurons compared with CT and GSP neurons (Fig. 2D).

T-type Ca2+ currents of GG neurons

There were differences in the functional expression of T-type Ca2+ currents in the GG neuron subpopulations. T-type Ca2+ currents were present in 62.2% (28 of 45 neurons) of CT, 81.3% (26 of 32 neurons) of GSP, and 96.4% (27 of 28 neurons) of PA neurons (Fig. 3A). Neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents were more frequently encountered in PA neurons than in CT neurons (χ2 test: P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of T-type Ca2+ current characteristics in different subpopulations of GG neurons. A: histogram of the percentage of CT, GSP, and PA neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents. More PA neurons (27 of 28) had T-type Ca2+ currents than CT (28 of 45) and GSP neurons (26 of 32). B: frequency distributions of soma diameters of CT neurons with and without T-type Ca2+ currents. The data points are fitted by normal distribution curves (continuous curves). Average soma diameter of CT neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents was significantly different from CT neurons without T-type Ca2+ currents (P < 0.01). C: representative T-type Ca2+ current traces evoked by a step pulse from a holding potential of −90 mV to a test potential of −40 mV in a CT, GSP, and PA neuron. The amplitude of T-type Ca2+ current was larger in the PA neuron than the CT and the GSP neuron. D: histogram of the average T-type Ca2+ current density for CT, GSP, and PA neurons. There was a significant difference in the T-type Ca2+ current density between CT, GSP, and PA neurons (P < 0.05 or higher).

Distribution of average soma diameter differed in CT neurons with and without T-type Ca2+ currents (Fig. 3B). The average diameter was 28.8 ± 0.3 μm for CT neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents (n = 28) and 25.7 ± 0.7 μm for CT neurons without T-type Ca2+ currents (n = 17), respectively, a significant difference (P < 0.01). Diameters of GSP and PA neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents (GSP: 27.2 ± 0.3 μm, n = 26; PA: 29.3 ± 0.3 μm, n = 27) did not differ from diameter of GSP and PA neurons that did not express T-type Ca2+ currents (GSP: 27.2 ± 1.6 μm, n = 6; PA: 28.0 μm, n = 1). However, this result may be influenced by the low numbers of GSP and PA neurons without T-type Ca2+ currents that we encountered.

We compared T-type Ca2+ current amplitudes evoked by a step pulse from a holding potential of −90 mV to a test potential of −40 mV in the neurons expressing T-type Ca2+ currents in three subpopulations of GG neurons (Fig. 3C). The T-type Ca2+ current amplitude was significantly larger in PA neurons (1,042.3 ± 70.1 pA, n = 27) than in CT (729.6 ± 50.4 pA, n = 28; P < 0.01) and GSP neurons (595.8 ± 63.2 pA, n = 26; P < 0.01). Because differences in cell size of GG neurons tested could affect the amplitude of T-type Ca2+ currents, we compared the current density of T-type Ca2+ current by dividing the current amplitude (pA) by the cell capacitance (pF). The T-type Ca2+ current density was significantly larger in PA neurons (31.3 ± 1.5 pA/pF, n = 27) than in CT (24.9 ± 1.6 pA/pF, n = 28; P < 0.05) and GSP neurons (19.4 ± 1.6 pA/pF, n = 26; P < 0.01; Fig. 3D). Furthermore, GSP neurons had a significantly smaller T-type Ca2+ current density than CT neurons (P < 0.01). There was a weak correlation between cell size and T-type Ca2+ current density in neurons with T-type Ca2+ currents (R = 0.29).

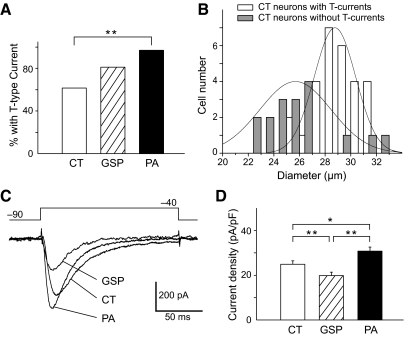

We studied the voltage-dependent activation of the T-type Ca2+ currents by applying 150-ms step pulses to test potentials from – 80 to – 40 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of –90 mV (Fig. 4A). Resulting data for 8 CT, 7 GSP, and 12 PA neurons were fitted with a Boltzmann equation. The T-type Ca2+ currents showed similar (P > 0.05) half-activation values (CT −46.1 ± 1.3 mV; GSP −45.5 ± 0.4 mV; PA −46.9 ± 0.7 mV) and slopes of the activation curves (Fig. 4C). We also measured the steady-state inactivation by varying the holding potentials at voltages from –100 to –40 mV for 2 s in 10-mV increments before changing the voltage to the test potential of –40 mV for 250 ms (Fig. 4B). The half-inactivation voltages (CT −67.1 ± 1.1 mV; GSP −66.9 ± 0.5 mV; PA −65.8 ± 0.7 mV) and slopes of the inactivation curves were also similar (P > 0.05) between the three subpopulations of GG neurons (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Voltage dependence of activation and steady-state inactivation for T-type Ca2+ currents in different subpopulations of GG neurons. A: representative current traces evoked by 150 ms step pulses to test potentials from −80 to −40 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −90 mV to investigate the voltage dependence of activation. B: representative current traces by varying the holding potentials from −100 to −40 mV for 2 s in 10 mV increments before changing the voltage to the test potential of −40 mV for 250 ms for the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation. The bottom panels indicate voltage protocols. C: activation curve obtained from CT (□), GSP (○), and PA neurons (▵). Relative conductance (G/Gmax) of T-type Ca2+ current was plotted against membrane potential. D: steady-state inactivation curve from CT (□), GSP (○), and PA neurons (▵). Normalized current (I/Imax) was plotted against membrane potential. Data were fitted with a Boltzmann curve. There were no significant differences in the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of the T-type Ca2+ currents between 3 subpopulations of GG neurons (P > 0.05).

HVA Ca2+ currents of GG neurons

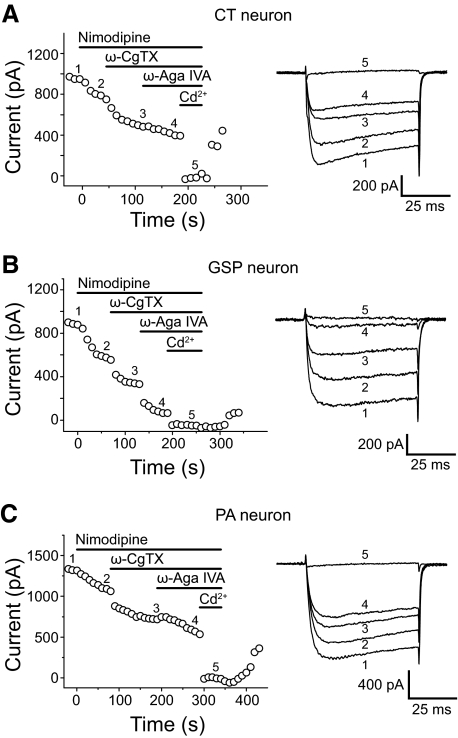

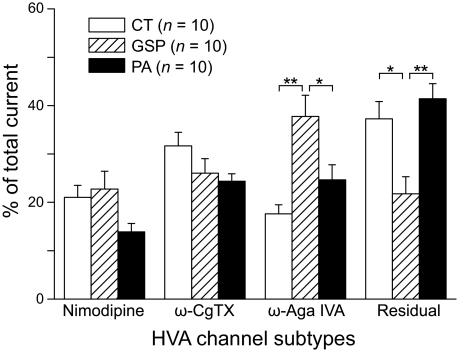

We used pharmacological antagonists to characterize subtypes of HVA calcium channels in subpopulations of GG neurons (10 CT, 10 GSP, and 10 PA). HVA Ca2+ currents were evoked by depolarization from −60 to −10 mV for 80 ms and the peak amplitude of the current plotted as a function of time (Fig. 5, A–C). Sequential applications of 5 μM nimodipine (L-type channel antagonist), 1 μM ω-CgTX (N-type channel antagonist), and 200 nM ω-Aga IVA (P/Q-type channel antagonist) inhibited part of the current in all CT (Fig. 5A), GSP (Fig. 5B), and PA neurons (Fig. 5C). A residual current remained, resistant to the combined antagonist application. Application of the nonselective Ca2+ current antagonist Cd2+ (100 μM) completely blocked the remaining Ca2+ currents, indicating the presence of R-type Ca2+ currents. Inhibition by the antagonists was partially reversible. Figure 6 summarizes the effects of the antagonists as a mean percentage of total current in the different subpopulations of GG neurons. Nimodipine application blocked 21.0 ± 2.5 (CT), 22.8 ± 3.7 (GSP), and 13.9 ± 1.8% (PA) of the total currents in GG neuron subpopulations. Subsequent application of ω-CgTX reduced 31.7 ± 2.8 (CT), 26.0 ± 3.0 (GSP), and 24.4 ± 1.5% (PA) of the current and ω-Aga IVA produced an additional 17.6 ± 1.9 (CT), 37.8 ± 4.4 (GSP), and 24.7 ± 1.5% (PA) reduction of the current. Residual fractions were 37.3 ± 3.6 (CT), 21.8 ± 3.5 (GSP), and 41.4 ± 3.2% (PA). The percentage of P/Q type Ca2+ current blocked by ω-Aga IVA was significantly greater in GSP neurons than CT and PA neurons (P < 0.01). In contrast, the residual fraction (estimated R-type Ca2+ current component) of Ca2+ current was significantly smaller in GSP neurons than CT and PA neurons (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the percentage of L-and N-type Ca2+ currents reduced by nimodipine and ω-CgTX between CT, GSP, and PA neurons.

Fig. 5.

Blocking effects of calcium channel antagonists on HVA Ca2+ currents in different subpopulations of GG neurons. HVA Ca2+ currents were evoked by repetitive constant step pulses to a test potential of −10 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV in CT (A), GSP (B), and PA neurons (C). Peak amplitude of current was plotted against time (A–C, left). Superimposed current traces in the right in A–C were selected from continuous recordings in the left at the locations indicated by corresponding numbers (labeled 1–5). Sequential application of nimodipine (5 μM), ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTX, 1 μM), and ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-Aga IVA, 200 nM) reduced the part of HVA Ca2+ currents but did not completely suppress HVA currents. Cd2+ (100 μM) completely blocked all the remaining currents.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the different subtypes of Ca2+ currents in different subpopulations of GG neurons. Histogram shows the average percentage of total Ca2+ current blocked by nimodipine, ω-CgTX, and ω-Aga IVA in CT (n = 10), GSP (n = 10), and PA neurons (n = 10), obtained in experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 5. The residual component was estimated as the fraction of Ca2+ currents resistant to nimodipine, ω-CgTX, and ω-Aga IVA. There were significant differences in the percentage of P/Q-type Ca2+ current blocked by ω-Aga IVA and residual fraction of Ca2+ current between 3 subpopulations of GG neurons (P < 0.01 or higher).

Action potential and afterdepolarization of GG neurons

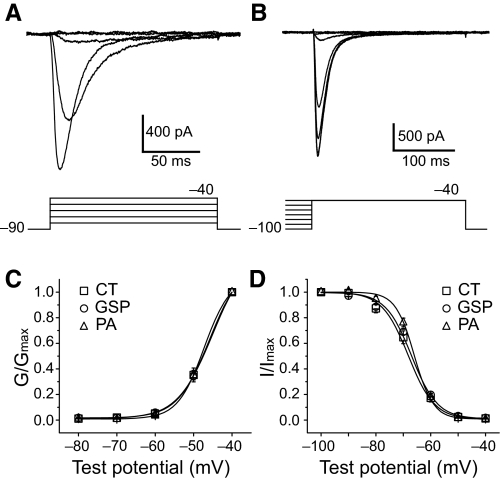

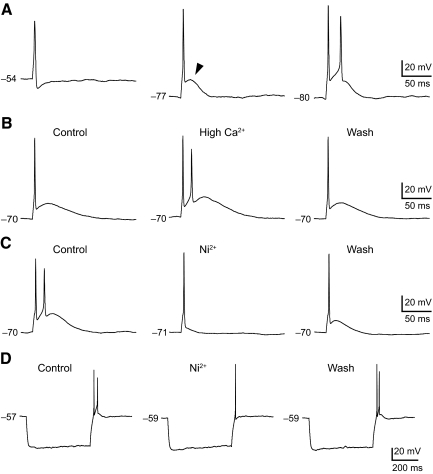

We used current-clamp recordings to study the contribution of Ca2+ currents to the spike firing of GG neuron subpopulations. Current-clamp recordings were performed on 14 CT, 13 GSP, and 11 PA neurons. Resting membrane potentials of all neurons ranged from −41 to −64 mV, with a mean of −56 ± 1 (CT neurons), −56 ± 1 (GSP neurons), and −54 ± 2 mV (PA neurons), respectively. There were no significant differences in the resting membrane potential between three subpopulations of GG neurons (P > 0.05). Figure 7A shows examples of action potential elicited from various membrane potentials in GG neurons. A single action potential was evoked by injection of brief depolarizing current pulses (3 ms), which was followed by an afterhyperpolarization (AHP) at resting membrane potential (Fig. 7A, left). When the cell membrane potential was hyperpolarized at −77 mV, a humplike afterdepolarization (ADP) was elicited following the rapid repolarizing phase of the spike (filled arrowhead in Fig. 7A, middle). Holding the cell membrane at a more negative potential of −80 mV produced a strong enhancement of the ADP that elicited another spike (Fig. 7A, right). Figure 7B exhibits the effect of change in extracellular Ca2 concentration on ADP. The ADP was strongly enhanced by increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 2 (Fig. 7B, left) to 6 mM (Fig. 7B, middle).

Fig. 7.

Action potential and afterdepolarization (ADP) in different subpopulations of GG neurons. A: action potential evoked from successively more hyperpolarized membrane potentials. Note that the ADP was elicited from a membrane potential of −77 mV (arrowhead in the middle). B: effect of change in extracellular Ca2+ concentration. An action potential and ADP were evoked in 2 mM Ca2+ (control, left), 6 mM Ca2+ (high Ca2+, middle), and after returning to 2 mM Ca2+ (wash, right) in external solution in the same neuron. Increasing extracellular Ca2+ concentration caused a strong and reversible enhancement of the ADP. C: effect of Ni2+ application on ADP. Application of Ni2+ (200 μM) abolished the ADP and the additional spike (middle). The ADP returned partially after washout (right). D: effect of Ni2+ on rebound spike evoked after hyperpolarizing current pulses from resting membrane potential: 200 μM Ni2+ decreased the number of the rebound spikes (middle). The effect of Ni2+ was reversed after washout (right).

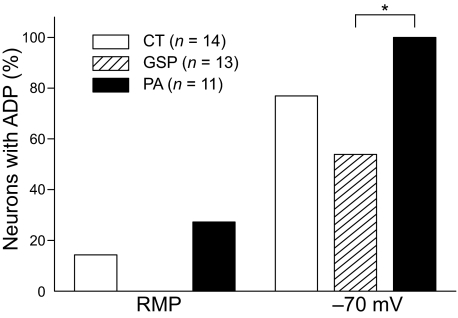

Previous studies indicate that T- and R-type Ca2+ currents are involved in the generation of the ADP and additional spikes that trigger burst firing in some acutely isolated rat dorsal root ganglion neurons (Metz et al. 2005; White et al. 1989). Therefore we applied the antagonist to the GG neurons. As shown in Fig. 7, application of 200 μM Ni2+, which blocks both T- and R-type calcium currents, abolished the ADP with burst firing (Fig. 7C, middle). The effect of Ni2+ was partially reversible (Fig. 7C, right). Furthermore, the number of rebound spikes elicited after hyperpolarizing current pulses injection (500 ms) from a resting membrane potential was reduced by application of Ni2+ (Fig. 7D, middle). ADPs were observed in 77% (11 of 14 neurons) of CT, 58% (7 of 13 neurons) of GSP, and 100% (11 of 11 neurons) of PA at a membrane potential of −70 mV, whereas only 14% (2 of 14 neurons) of CT, 0% (0 of 13 neurons) of GSP, and 27% (3 of 11 neurons) of PA neurons displayed ADPs at resting membrane potentials (Fig. 8). All PA neurons expressed ADPs at a hyperpolarized membrane potential, whereas GSP neurons with ADPs were less frequent encountered compared with PA neurons (Fisher's exact test: P < 0.05).

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the frequency of neurons with ADPs in different subpopulations of GG neurons. Histogram of the percentages in CT, GSP, and PA neurons with ADPs at resting membrane potential (RMP) and at a membrane potential of −70 mV. The frequency of PA neurons with ADP (11 of 11 neurons) was significantly higher than GSP neurons (7 of 13 neurons) at a membrane potential of −70 mV (Fisher's exact test: P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our data provide a compelling demonstration of heterogeneity among GG neurons with different receptive fields on the anterior tongue, soft palate, and ear innervated by the CT, GSP, and PA branches of the facial nerve. Results establish that isolated CT, GSP, and PA neurons differ in size, expression of calcium channels, and action potential characteristics. PA neurons were significantly larger than CT and GSP neurons, and CT neurons could be further subdivided based on soma diameter. Both LVA and HVA Ca2+ currents were expressed in all GG neuron groups, but there were significant differences in biophysical properties and percentage of different Ca2+ currents in neurons of the CT, GSP, and PA nerves. In addition, in current-clamp experiments, a brief depolarization generated an ADP that was Ca2+ current initiated. This heterogeneity is a fundamental characteristic of the basic neurobiology of the GG related to the diverse function of the sensory information transmitted by the CT, GSP, and PA branches of the facial nerve.

GG neuron differ in several properties related to function

Heterogeneity in other sensory ganglia neurons has been correlated with different sensory function. Most available information on ganglion cell properties is derived from studies of the dorsal root ganglion. Neurons in this ganglion differ in soma size and peripheral fiber diameter and conduction velocity (Harper and Lawson 1985) and can also be subdivided based on their response to adequate stimuli (Lawson 2002). The biophysical properties of the ganglion soma differ, and these differences correlate with the type of peripheral receptors they innervate (Koerber et al. 1988). In addition, dorsal root ganglion nociceptive fibers have been found to be separable into two major classes based on molecular and anatomical criteria. These two classes also express different ion channels and have different central and peripheral terminations (Braz et al. 2005; Woolf and Ma 2007; Zylka et al. 2005). Based on this and considerable other information on the dorsal root ganglion, it is reasonable to assume that the different properties we reported for GG neurons relate to similar correlations between ganglion cell properties and function.

Peripheral fibers of GG neurons differ in size. Investigators have reported a bimodal distribution of CT axon diameters (Jang and Davis 1987). Axon diameters of the CT in rat and hamster have been measured after the parasympathetic efferent fiber component was eliminated by section of the central process (nervus intermedius). Seventy-nine percent of the afferent processes of the CT were myelinated fibers and only 30% were unmyelinated (Farbman and Hellekant 1978). The myelinated axons range from 1 to 5 μm in diameter and the unmyelinated range from 0.2 to 1.5 μm. Data from the hamster CT show a bimodal distribution of axon diameters with equal proportions of myelinated and unmyelinated fibers (Jang and Davis 1987). Thus there is considerable variability in the distribution of CT axon diameters. No information is available for GSP and PA axon diameters.

Using extracellular recording from rat GG soma, investigators provided information on chemical and thermal responses of neurons with afferent fibers in the CT and GSP (Breza et al. 2006; Lundy and Contreras 1999; Sollars and Hill 2005). Stimuli representing the taste qualities (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami) and thermal stimuli were applied to the anterior tongue and soft palate. Neurons of the GG innervating the tongue were divided into those that responded to a single stimulus (either NaCl or sucrose and called “specialists”) and those that responded to several of the applied stimuli and were classified as “generalists” (Lundy and Contreras 1999; Sollars and Hill 2005). The temperature sensitivity of the CT GG neurons was also examined (Breza et al. 2006). The majority of the neurons that responded to either warming or cooling were either NaCl specialists or acid-sensitive generalists. When responses of GG somata innervating the tongue and soft palate were compared, differences in response characteristics were found and assumed to reflect the response characteristics of the taste buds in the two receptive fields (Hendricks et al. 2002; Nejad 1986; Sollars and Hill 1998, 2000, 2005). However, it is also possible that these differences in response characteristics may relate to the biophysical properties of the GG neurons reported in these experiments.

Recordings from peripheral fibers also show the heterogeneous characteristics of the GG neurons. CT fibers are relatively nonspecific in their response to chemicals representing the taste qualities (Erickson et al. 1965; Fishman 1957; Frank et al. 1988; Ogawa et al. 1968; Pfaffmann 1941, 1955). However, even though fibers were not found to respond exclusively to one of the taste qualities, CT fibers could be grouped based their “best” response to lingual application of taste stimuli (Frank 1974; Frank et al. 1988). Furthermore, despite the fact that the CT is often referred to as a “pure taste” nerve (Arai et al. 2010), numerous electrophysiological studies using chemical, thermal, and tactile stimuli report that, in rat, hamster, and several other species, many CT fibers are multimodal (Breza et al. 2006, 2010; Kosar and Schwartz 1990; Ogawa et al. 1968; Sato et al. 1975; Shimatani et al. 2002). Afferents fibers of GG neurons also transmit different sensory information. However, investigators exploring response properties of GG neurons have restricted their analysis to CT neurons of rats and hamsters with the goal of determining how chemosensory information is encoded.

There are a few reports of whole nerve responses of the GSP nerve to chemical stimulation of the soft palate (Harada and Smith 1992; Nejad 1986; Sollars and Hill 2000), but no reports using single fiber recordings, and to date, no studies of the response properties of the PA nerve have appeared.

Correlation of GG cell soma size with afferent fiber characteristics

Early investigators correlated CT fiber diameter with response characteristics to chemical stimuli. CT fibers in dogs responding to sweet tasting stimuli were reported to be larger than fibers responsive to tongue application of bitter tasting compounds (Andersson et al. 1951). In a later study, all the CT taste fibers were reported to be in the Aδ conducting range, although they varied between 17.8 and 1.6 m/s (Iriuchijima and Zotterman 1961). Taste fibers that responded to bitter tasting stimuli were smaller than the fibers responding to the other taste qualities, and their conduction velocities were in the upper range of C fibers. The data from the CT were restricted to chemical stimuli, and no data are available on conduction velocity measures for GSP and PA afferent fibers. These early studies have to be evaluated based on many later studies. For example, rat GG tongue neurons that respond to bitter tasting chemicals were classified as generalists, and thus it is not possible to conclude that all small diameter fibers relay information only on bitter taste. In a recent study in which response latency was accurately measured, part of which is contributed by fiber conduction velocity, GG neurons with the shortest latency were those that responded best to a single stimulus (Breza et al. 2010). This suggests that the short latency GG neurons have the larger diameter peripheral fibers.

Potential role of GG neurons in sensory processing

We showed that the GG contains a diverse population of sensory neurons that encode a variety of stimuli with distinctly different electrophysiological properties. The calcium channels characterized in this study are responsible in part for these distinct properties. Besides a number of important roles, calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels is required for the release of neurotransmitter from synaptic endings (Hille 2001). However, the calcium currents in GG neurons were characterized in the ganglion cell and not the central synaptic terminals. Calcium currents have also been characterized in aortic baroreceptor neurons in the nodose ganglion (Mendelowitz and Kunze 1992). These currents were later determined to correspond to calcium channels in the central synapses (Mendelowitz et al. 1995), suggesting that calcium channels characterized in the soma reflect those at the central synapses. It is likely therefore that the calcium channels we described in GG soma play a role in synaptic transmission between the central processes and the second-order neurons in the rNST.

GG calcium channels may also be required for the release of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators involved in nonsynaptic communication between ganglion cells (Amir and Devor 1996; Utzschneider et al. 1992). Ganglion cells do not have synapses, yet respond to a number of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (Lieberman 1976). Calcium channels have been shown to be required for release of ATP and Substance P from trigeminal ganglion cells (Matsuka et al. 2001). GG ganglion cells respond to Substance P (Koga and Bradley 2000) and stain positive for ATP receptors (Ohmoto et al. 2008), suggesting a role for calcium channels in GG neuron cross-excitation. This chemical mediated excitation between ganglion cells would potentially alter both the across-fiber pattern of activity and receptive field size of the GG neurons (Amir and Devor 1996; Utzschneider et al. 1992). These interactions between neurons need to be considered when drawing conclusions of sensory coding mechanisms because investigators assume that gustatory afferents neurons constitute independent sensory channels.

In the trigeminal ganglia investigators have reported the role of extracellular calcium in desensitization of trigeminal ganglion neurons to capsaicin (Liu and Simon 1998, 2000; Neubert et al. 2000) acting via TRPV1 channels. Recently TRPV1 channels have been reported in GG neurons (Katsura et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2007), and TRPV1 immunoreactive fibers have been shown in taste papillae and taste buds innervated by the CT (Ishida et al. 2002; Kido et al. 2003). It is possible therefore that the calcium channels of the GG neurons play a similar role in TRPV1 channel desensitization.

Investigators recording from the GG cells do not mention the possibility that the discharge pattern of GG neurons differ from discharge pattern of action potentials traveling to the GG. However, our finding that a subgroup of GG neurons responds to depolarization by generating an ADP suggests possible modification of the discharge pattern. Neurons in several brain areas including the dorsal root ganglion respond with an ADP that elicits burst firing (White et al. 1989). As in this study, the ADP is eliminated after application of calcium channel antagonists. Both T- and R-type calcium channels have been shown to play a role in the generation of the ADP (Metz et al. 2005; White et al. 1989). Thus GG neurons may not play a “platonic” role (Llinás 1988) in sensory processing and by depolarization-initiated burst discharges add to the frequency of action potentials transmitted from the periphery.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC-000288 to R. M. Bradley.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Amir R, Devor M. Chemically mediated cross-excitation in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci 16: 4733–4741, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson B, Landgren S, Olsson L, Zotterman Y. The sweet taste fibres of the dog. Acta Physiol Scand 21: 105–119, 1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Ohkuri T, Yasumatsu K, Kaga T, Ninomiya Y. The role of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 on neural responses to acids by the chorda tympani, glossopharyngeal and superior laryngeal nerves in mice. Neuroscience 165: 1476–1489, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccei ML, Kocsis JD. Voltage-gated calcium currents in axotomized adult rat cutaneous afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol 83: 2227–2238, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. Classes of calcium channels in vertebrate cells. Annu Rev Physiol 51: 367–384, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau JC, Hoang NK, Oravec J, Do LT. Rat neurophysiological taste responses to salt solutions. Chem Senses 8: 131–150, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau JC, Sivakumar L, Do LT, White TD, Oravec J, Hoang NK. Neurophysiology of geniculate ganglion (facial nerve) taste systems: species comparisons. Chem Senses 10: 89–128, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Braz JM, Nassar MA, Wood JN, Basbaum AI. Parallel “pain” pathways arise from subpopulation of primary afferent nociceptor. Neuron 47: 787–793, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breza JM, Curtis KS, Contreras RJ. Temperature modulates taste responsiveness and stimulates gustatory neurons in the rat geniculate ganglion. J Neurophysiol 95: 674–685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breza JM, Nikonov AA, Contreras RJ. Response latency to lingual taste stimulation distinguishes neuron types within the geniculate ganglion. J Neurophysiol 103: 1771–1784, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal A. Neurological Anatomy in Relation to Clinical Medicine. New York: Oxford, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo A, Zucchi B, Pereira E, Roper SD. Rat gustatory neurons in the geniculate ganglion express glutamate receptor subunits. Chem Senses 29: 463–471, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante P, Cardenas CG, Whittaker JA, Kitai ST, Scroggs RS. Low-threshold L-type calcium channels in rat dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol 91: 1450–1454, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson RP, Doetsch GS, Marshall DA. The gustatory neural response function. J Gen Physiol 49: 247–263, 1965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbman AI, Hellekant G. Quantitative analyses of the fiber population in rat chorda tympani nerves and fungiform papillae. Am J Anat 153: 509–522, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman IY. Single fiber gustatory impulses in rat and hamster. J Cell Comp Physiol 49: 319–334, 1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M. The classification of mammalian afferent taste nerve fibers. Chem Senses Flav 1: 53–60, 1974 [Google Scholar]

- Frank ME, Bieber SL, Smith DV. The organization of taste sensibilities in hamster chorda tympani nerve fibers. J Gen Physiol 91: 861–896, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MM. Afferent soma populations within the geniculate ganglion. Abst Soc Neurosci 4: 87, 1978 [Google Scholar]

- Grigaliunas A, Bradley RM, Maccallum DK, Mistretta CM. Distinctive neurophysiological properties of embryonic trigeminal and geniculate neurons in culture. J Neurophysiol 88: 2058–2074, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S, Smith DV. Gustatory sensitivities of the hamster's soft palate. Chem Senses 17: 37–51, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Conduction velocity is related to morphological cell type in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol 359: 31–46, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks SJ, Sollars SI, Hill DL. Injury-induced functional plasticity in the peripheral gustatory system. J Neurosci 22: 8607–8613, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Iriuchijima J, Zotterman Y. Conduction rates of afferent fibres to the anterior tongue of the dog. Acta Physiol Scand 51: 283–289, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Murakami S, Shimada S. Vanilloid receptor subtype-1 (VR1) is specifically localized to taste papillae. Mol Brain Res 107: 17–22, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang T, Davis BJ. The chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves in the adult hamster. Chem Senses 12: 381–395, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Katsura H, Tsuzuki K, Noguchi K, Sagami M. Differential expression of capsaicin-, menthol-, and mustard oil-sensitive receptors in naive rat geniculate ganglion neurons. Chem Senses 31: 681–688, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido MA, Muroya H, Yamaza T, Terada Y, Tanaka T. Vanilloid receptor expression in the rat tongue and palate. J Dent Res 82: 393–397, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Chung MK. Voltage-dependent sodium and calcium currents in acutely isolated adult rat trigeminal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol 81: 1123–1134, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Bradley RM, Mistretta CM. TRPV2 expression in geniculate and petrosal ganglia and the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract. Chem Senses 32: 653, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- King MS, Bradley RM. Biophysical properties and responses to glutamate receptor agonists of identified subpopulations of rat genigulate ganglion neurons. Brain Res 866: 237–246, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K, Kimura RS, Schuknecht HF. The ultrastructure of the geniculate ganglion. Acta Otolaryngol 93: 175–186, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Hendricks G, Hermann G, Rogers RC, Kunze DL. Dopamine inhibits N-type channels in visceral afferents to reduce synaptic transmitter release under normoxic and chronic intermittent hypoxic conditions. J Neurophysiol 101: 2270–2278, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Druzinsky RE, Mendell LM. Properties of somata of spinal dorsal root ganglion cells differ according to peripheral receptor innervated. J Neurophysiol 60: 1585–1596, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Mendell LM. Functional heterogeneity of dorsal root ganglion cells. In: Sensory Neurons: Diversity, Development, and Plasticity, edited by Scott SA. New York: Oxford, p. 77–96, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Bradley RM. Biophysical properties and responses to neurotransmitters of petrosal and geniculate ganglion neurons innervating the tongue. J Neurophysiol 84: 1404–1413, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosar E, Schwartz GJ. Effects of menthol on peripheral nerve and cortical unit responses to thermal stimulation of the oral cavity in the rat. Brain Res 513: 202–211, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson SN. Phenotype and function of somatic primary afferent nociceptive neurones with C-, Aδ- or Aα/β-fibres. Exp Physiol 87: 239–244, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Smith DV. Glutamate receptor antagonists block gustatory afferent input to the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol 77: 1514–1525, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AR. Sensory ganglia. In: The Peripheral Nerve, edited by Landon DN. London: Chapman and Hall, p. 188–278, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Simon SA. The influence of removing extracellular Ca2+ in the desensitization responses to capsaicin, zingerone and olvanil in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons. Brain Res 809: 246–252, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Simon SA. Capsaicin, acid and heat-evoked currents in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons: relationship to functional VR1 receptors. Physiol Behav 69: 363–378, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás RR. The intrinsic electrophysiological properties of mammalian neurons: insights into central nervous system function. Science 242: 1654–1664, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy RF, Contreras RJ. Gustatory neuron types in rat geniculate ganglion. J Neurophysiol 82: 2970–2988, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuka Y, Neubert JK, Maidment NT, Spigelman I. Concurrent release of ATP and substance P within guinea pig trigeminal ganglia in vivo. Brain Res 915: 248–255, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto I, Emori Y, Ninomiya Y, Abe K. A comaparative study of three cranial sensory ganglia projecting into the oral cavity: in situ hybridization analyses of neurotropin receptors and themosensitive cation channels. Mol Brain Res 93: 105–112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May OL, Hill DL. Gustatory terminal field organization and developmental plasticity in the nucleus of the solitary tract revealed through triple-fluorescence labeling. J Comp Neurol 497: 658–669, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SB, Priestley JV. Nociceptor plasticity. In: The Neurobiology of Pain, edited by Hunt SP, Koltzenburg M. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 35–64, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D, Kunze DL. Characterization of calcium currents in aortic baroreceptor neurons. J Neurophysiol 68: 509–517, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D, Reynolds PJ, Andresen MC. Heterogeneous functional expression of calcium channels at sensory and synaptic regions in nodose neurons. J Neurophysiol 73: 872–875, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz AE, Jarsky T, Martina M, Spruston N. R-Type calcium channels contribute to afterdepolarization and bursting in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 25: 5763–5773, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ. Calcium signalling in neurons. Trends Neurosci 11: 415–419, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ. Multiple calcium channels and neuronal function. Science 235: 46–32, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawar NNY, Mikhail Y, Ibrahim KA. Quantitative and histomorphological studies on the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve in man. Acta Anat 106: 57–62, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejad MS. The neural activities of the greater superficial petrosal nerve of the rat in response to chemical stimualtion of the palate. Chem Senses 11: 283–293, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Neubert JK, Maidment NT, Matsuka Y, Adelson DW, Kruger L, Spigelman I. Inflammation-induced changes in primary afferent-evoked release of substance P within trigeminal ganglia in vivo. Brain Res 871: 181–191, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Sato M, Yamashita S. Multiple sensitivity of chorda tympani fibers of the rat and hamster to gustatory and thermal stimuli. J Physiol 199: 223–240, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Yasuoka A, Yoshihara Y, Abe K. Genetic tracing of the gustatory and trigeminal neural pathways originating from T1R3-expressing taste receptor cells and solitary chemoreceptor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 38: 505–517, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AV, Krimm RF. BDNF is required for the survival of differentiated geniculate ganglion neurons. Dev Biol 340: 419–429, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffmann C. Gustatory afferent impulses. J Cell Comp Physiol 17: 243–258, 1941 [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffmann C. Gustatory nerve impulses in rat, cat, and rabbit. J Neurophysiol 18: 429–440, 1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Ogawa H, Yamashita S. Response properties of macaque monkey chorda tympani fibers. J Gen Physiol 66: 781–810, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Distribution of dihydropyridine and omega-conotoxin-sensitive calcium currents in acutely isolated rat and frog sensory neuron somata: diameter-dependent L channel expression in frog. J Neurosci 11: 1334–1346, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. J Physiol 445: 639–658, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba K, Sood V, Shu NY, Nagele RG, Egger MD. Examination of geniculate ganglion cells contributing sensory fibers to the rat facial ‘motor’ nerve. Neurosci Lett 308: 354–359, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher E, Biancardi E, Passafaro M, Clementi F. Physiopathology of neuronal voltage-operated calcium channels. FASEB J 5: 2677–2683, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimatani Y, Grabauskiene S, Bradley RM. Long-term recording from the chorda tympani in rats. Physiol Behav 76: 143–149, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollars SI, Hill DL. Taste responses in the greater superficial petrosal nerve: Substantial sodium salt and amiloride sensitivities demonstrated in two rat strains. Behav Neurosci 112: 991–1000, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollars SI, Hill DL. Lack of functional and morphological susceptibility of the greater superficial petrosal nerve to developmental dietary sodium restriction. Chem Senses 25: 719–727, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollars SI, Hill DL. In vivo recordings from rat geniculate ganglia: taste response properties of individual greater superficial petrosal and chorda tympani neurones. J Physiol 564: 877–893, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swandulla D, Carbone E, Lux HD. Do calcium channel classifications account for neuronal calcium channel diversity? Trends Neurosci 14: 46–51, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzschneider D, Kocsis J, Devor M. Mutual excitation among dorsal root ganglion neurons in the rat. Neurosci Lett 146: 53–56, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Bradley RM. In vitro study of afferent synaptic transmission in the rostral gustatory zone of the rat nucleus of the solitary tract. Brain Res 702: 188–198, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Bradley RM. Synaptic characteristics of rostral nucleus of the solitary tract neurons with input from the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves. Brain Res 1328: 71–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G, Lovinger DM, Weight FF. Transient low-threshold Ca2+ current triggers burst firing through an afterdepolarizing potential in an adult mammalian neuron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 6802–6806, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead MC, Frank ME. Anatomy of the gustatory system in the hamster: central projections of the chorda tympani and the lingual nerve. J Comp Neurol 220: 378–395, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Ma QF. Nociceptors-noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron 55: 353–364, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylka MJ, Rice FL, Anderson DJ. Topographically distinct epidermal nociceptive circuits revealed by axonal tracers targeted to Mrgprd. Neuron 45: 17–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]