Abstract

We present 3D linear reconstructions of time-domain (TD) diffuse optical imaging differential data. We first compute the sensitivity matrix at different delay gates within the diffusion approximation for a homogeneous semi-infinite medium. The matrix is then inverted using spatially varying regularization. The performances of the method and the influence of a number of parameters are evaluated with simulated data and compared to continuous-wave (CW) imaging. In addition to the expected depth resolution provided by TD, we show improved lateral resolution and localization. The method is then applied to reconstructing phantom data consisting of an absorbing inclusion located at different depths within a scattering medium.

1. Introduction

In complement of traditional techniques such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Diffuse Optical Tomography (DOT) is emerging as a low-cost and portable method for non-invasive cerebral imaging [1–3]. Based on the measurement of diffuse near-infrared light attenuation through the scalp, skull and brain, DOT assesses local optical absorption due essentially to the concentrations in oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin. Modeling of light propagation through the head and solving of the inverse problem enable imaging of total hemoglobin concentration and oxygenation in the brain.

Most DOT instruments used in neuroscience are continuous wave (CW) systems, but time-domain (TD) technology is a recent promising alternative with advantages compensating for its increased cost and difficulty of implementation. These advantages include absolute characterization of tissue optical properties [4,5] (both absorption coefficient μa and reduced scattering coefficient μs′), depth resolution with single source-detector separation [6,7], and better sensitivity to cortical activation [8,9]. TD systems introduce short pulses of light into the tissue (up to tens to hundreds of picoseconds) and measure the temporal point spread function (TPSF) of photons exiting after propagation through the tissue.

One application of TD system is the determination of the absolute optical properties μa and μs′ of a tissue. One to several source-detector pairs are placed on the surface of the studied organ. The measured TPSFs [10,11], or moments of these TPSFs [12–14] are fit non-linearly with a model of light propagation in a homogeneous medium [4,11], a two-layer medium [15,16], a more realistic tissue-type segmentation of the head [17], or a complete voxelized volume in the case of tomographic imaging [18,19].

However, for functional studies, differential imaging between a baseline state and an activated state is sufficient, and a linear relation between changes in absorption and changes in intensity is generally assumed valid for the small absorption changes associated with brain function. In the backprojection method widely used for CW data reconstruction [20–23], the change in intensity between each source and detector is translated into a local change in absorption. A two-dimensional image is obtained by interpolation of all local absorption changes. The method is based on a modified Beer-Lambert law where a differential path factor (DPF) accounts for larger propagation length than source-detector separation [24]. Hiraoka et al. extended the concept to inhomogeneous media [25], by introducing partial DPFs describing the optical pathlengths in different tissue types, hence taking into account the contribution from different layers to the change in attenuation. However, no depth information is available with single distance CW data, and both cerebral and superficial activations are projected on a single imaging plane.

This limitation of NIRS imaging in terms of depth resolution can be overcome with TD data, where depth information is contained in the photons’ time of flights. Steinbrink et al. applied the concept of partial DPFs to the time domain by introducing time-dependant mean partial pathlengths (TMPP) [6]. They used a model of fifteen 2 mm thick layers, and performed Monte Carlo simulations to calculate the time-dependant sensitivity to each layer. They thus obtained a sensitivity matrix which they inverted by singular value decomposition. They could distinguish between extra and intra-cerebral signals during brain activation, with a single source-detector pair measurement. Liebert et al. used a similar method but computed the sensitivity of three moments of the TPSF – integrated intensity, mean time of flight, variance – to each layer [26]. They showed depth-resolved time-course of local perfusion after dye bolus injection on healthy subjects and stroke patients [27]. We used a simplified 3-layer model – scalp, skull, and brain – and showed that we could experimentally distinguish between superficial systemic signals and cerebral activation signals during a motor stimulus on a single source-detector pair [8]. In all these studies, depth resolution has been shown, but no 3D imaging was implemented, since a single source-detector pair was used. The technique can be extended to 2D imaging with depth resolution by simple interpolation of all source-detector pair’s measurements [28]. However, this approach limits the lateral resolution to approximately the source-detector separation.

In this paper, we describe an actual 3D linear reconstruction for differential imaging, based on inversion of the forward sensitivity matrix calculated in different delay gates, in a similar way that is sometimes implemented in CW DOT imaging [29]. We discuss the performance and limitations of the reconstruction technique with simulated data. As already demonstrated in previous papers, we show that TD offers the ability to localize the depth of absorption contrast, which is not achievable with single distance CW data. Furthermore, we demonstrate improved lateral resolution and localization for TD compared to CW. We then apply the reconstruction technique to phantom data obtained with our time-gated system [30].

2. Reconstruction principle

In this section, we describe the formalism implemented for the image reconstructions.

2.1 Medium and probe geometry

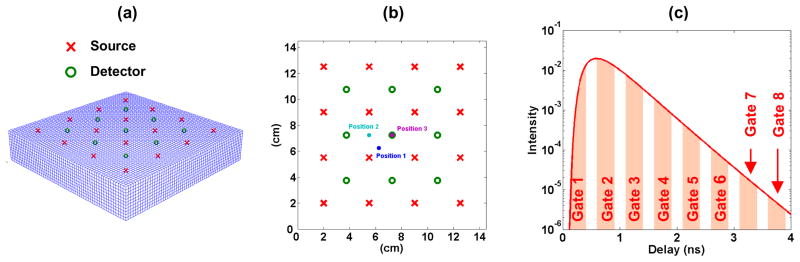

For computational simplicity, the studied medium is modeled as a volume of 10 cm by 10 cm laterally, and 3 cm in depth, divided into nvox voxels of 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm3 (see Fig. 1(a)). The background optical properties were set to μs′ = 10 cm−1 and μa = 0.1 cm−1, unless otherwise stated. The probe set on the surface of the medium has a square geometry of 4×4 sources and 3×3 detectors (source-detector separation 2.5 cm) as shown in Figs. 1(a) and 1(b). Only nearest neighbor source-detector pairs are taken into account for the reconstructions.

Fig. 1.

(a) 3D representation of the modeled medium and probe. (b) Probe geometry. Three lateral locations of the inclusion commonly used in the following simulations are also displayed (c) Simulated TPSF for one source-detector pair, with the delay gates used in the reconstruction.

2.2 Forward problem

We model light propagation in the medium with the analytical solution of the diffusion equation for a semi-infinite homogeneous medium, calculated with the image source technique [4], and extrapolated-boundary condition [31]. Figure 1(c) shows the resulting TPSF obtained for one source-detector pair, all source-detector pairs yielding identical TPSF’s since the medium is assumed semi-infinite and homogeneous. Since our experimental TD device described in Ref. 30 is based on a time-gated detection of the TPSF, we use in our simulations gated detection. The measurements consist in the intensity at nGates delay gates, integrated over the gate width wGate. The gates considered in our simulations are presented in Fig. 1(c). To comply with our experimental parameters [29], each gate width was set to 300 ps and the delay between two gates to 500 ps.

Differential images are obtained using the normalized Born approximation for a change in absorption: ΔI/I0 = A Δμa, where the sensitivity matrix A linearly relates the changes in the absorption coefficient to the changes in intensity. Δμa is the vector of absorption changes at each voxel, of length nvox, and ΔI/I0 is the vector of changes in the normalized measured intensity, of length the number of measurements nMeas = nSD nGates where nSD is the number of source-detector pairs and nGates the number of delay gates for each pair. In the time domain, the terms of the sensitivity matrix A can be computed by convolution of the direct and adjoint Green’s functions [32]:

where G(rS, rD, τ) is the time domain Green’s function (GF) solution of the diffusion equation at delay τ for a source at position rS and a detector at position rD, rj is the position of the jth voxel, and rS(i), rD(i) and τi are respectively the source position, detector position and delay of the ith measurement.

In practice, we first calculated the GFs solutions of the diffusion equation at each voxel of the medium in the frequency domain [32], for each optode (source or detector), at 101 frequencies (0 to 20 GHz, frequency step 200 MHz). The frequency-domain solutions were then Fourier-transformed to yield the GFs in the time domain with a 25 ps time step. To obtain the sensitivity matrix for each source-detector pair at a specific delay τ, the source forward GF at time τ′ and the detector adjoint GF at time τ-τ′ were multiplied, the result summed for τ′ varying between 0 and τ, and then integrated over the width wGate of the detection gate.

Note that alternative methods to compute the sensitivity matrix could be used, in particular analytical solutions in the time-domain for a perturbation, like described in Ref. [33] for a transmission geometry.

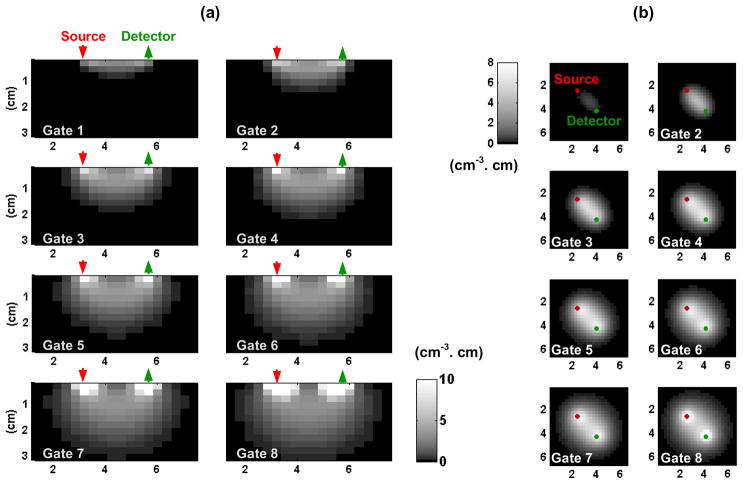

Figure 2 shows profiles of the obtained sensitivity matrix for the 8 delay gates depicted in Fig. 1(c) (delays between 0.1 and 3.6 ns with 500 ps between two gates; wGate = 300 ps). Figure 2(a) shows profiles of the sensitivity matrix along a source-detector vertical plane, and Fig. 2(b) shows (x,y) profiles of the matrix at depth z = 0.75 cm. A logarithmic grayscale was used to allow visualization of the large dynamic range of sensitivities of all 8 gates. As expected, sensitivities at longer delays go deeper inside the medium, and also probe a wider lateral region. From this additional information relative to traditional CW sensitivity profiles, we can expect both depth resolution and improved lateral resolution and localization.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity profiles of a single source-detector pair for the 8 delay gates presented in Fig. 1(c) in (a) a vertical plane along the source and detector and (b) a (x,y) plane located at depth 0.75 cm. The sensitivity is given per unit volume (cm3) and unit change in absorption (cm−1).

2.3 Inverse Problem

From the measurements y = ΔI/I0 and the computed sensitivity matrix A, the reconstructed image x̂ is calculated by inversion of the sensitivity matrix: x̂ = pAinvy, where pAinv is the pseudo-inverse of matrix A, computed with the following regularization:

| (1) |

where:

B = A L−1,

L = diag (diag (ATA + λ)) is used to scale the sensitivity matrix to act as a spatially varying regularization [34], giving higher weight to voxels with lower sensitivity. It is a diagonal matrix of size nvox × nvox where each diagonal element is the aggregate squared sensitivity to the corresponding voxel. The coefficient λ = max(diag(ATA))//β enables a thresholding of the matrix in order not to give large weighting to voxels with very small sensitivity. The choice of factor β will be discussed in section 3.4 below.

α is a regularization parameter, set to 10−3 in the simulations unless stated otherwise.

smax = max[diag (BBT)]/max(σy2),

σy2 is the measurement covariance matrix, assumed to be diagonal. In our simulations, we assumed a square root dependence of the noise on I with the intensity, and thus σy2 is inversely proportional to intensity. This regularization acts to penalize noisier measurements.

2.4. CW reconstructions

CW sensitivity matrix and data were simulated with the same model, by integration of TD data over all time steps. CW and TD reconstructions will be compared in Section 3 to assess the improvement offered by TD imaging.

3. Simulations: optimization, performance and comparison with CW

In this section, we assume a point-like change in absorption, simulate the corresponding measurement vector, and reconstruct the 3D map of the absorption changes. This gives us the imaging point spread function of our reconstruction algorithm and enables us to assess the performance of the method and compare it to a CW reconstruction scheme.

3.1 Reconstruction examples

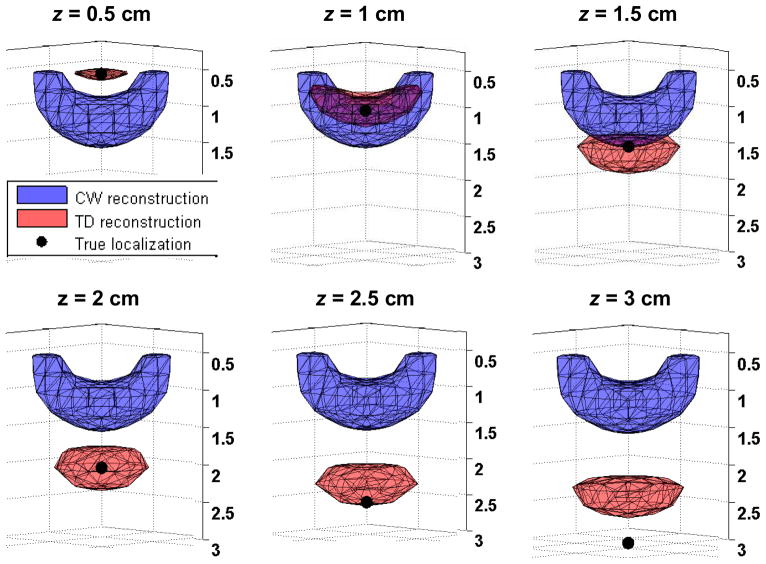

Figure 3 shows examples of reconstructions for a point-like inclusion located at the lateral position 1, between source and detector, as defined in Fig. 1(a), and with a depth z varying between 0.5 cm and 3 cm by steps of 0.5 cm. Both CW and TD reconstructions are presented. The rendered volume shows the contour of 80% of the maximum in the reconstructed absorption change. The following parameters were used: 5 gates starting at delays 0.6, 1.1, 1.6, 2.1, and 2.6 ns with a width wGate = 300 ps (gates 2 to 6 in Fig. 1(c)); β = 20; α = 10−3; signal to noise ratio = 100 at the peak of the TPSF.

Fig. 3.

CW and TD reconstructions of a point-like inclusion located at position 1 and at a depth z varying between 0.5 cm and 3 cm. The volumes show the contour of 80% of the maximum reconstructed change in absorption.

The following general observations can be made: the CW data always reconstruct the inclusion at the same depth. If a traditional Tikhonov regularization is used instead (i.e. if A is used in place of B in Eq.1), the CW reconstruction is pulled towards the surface (data not shown), where the sensitivity is maximum [35]. The effect of the spatially varying regularization matrix L is to force the reconstruction deeper under the surface. However, the reconstructed depth is unchanged with different actual depths for the CW data.

On the contrary, the TD method reconstructs the inclusion deeper as its actual depth increases. For the true inclusion at a depth of 1.5 and 2 cm, the reconstructed depth is actually slightly over-estimated, which results from the effect of the regularization matrix L. As the true inclusion gets deeper, the reconstructed depth becomes under-estimated (see inclusion at true depth 3 cm).

We also observe that the reconstructed volume at 80% of the maximum contrast is smaller for TD than for CW reconstructions, showing improved lateral resolution for this location of the inclusion.

More quantitative and systematic assessment of the effect of different parameters and of the improvement of TD over CW will be investigated in the following paragraphs.

3.2 Performance assessment

The reconstruction performances were assessed by a number of parameters. The location of the center of mass (COM) of the reconstructed inclusion was calculated by taking into account all voxels with a contrast above 80% of the maximum contrast in absorption: rCOM = (Σi, Vox≥80% Riri)/(Σi, Vox≥80% Ri), where ri and Ri are respectively the position and absorption contrast of the ith voxel. We define the localization error as the distance between the true inclusion and the COM, both in depth and laterally. We call lateral resolution the contrast-weighted sum of the lateral distances to the COM, over all voxels with a contrast above 80% of the maximum contrast: Res = (Σi, Vox≥80% Ri|ρi − ρCOM|)/(Σi, Vox≥80% Ri), where ρi and ρCOM are the lateral positions of the ith voxel and the COM respectively.

3.3 Optimal number of gates

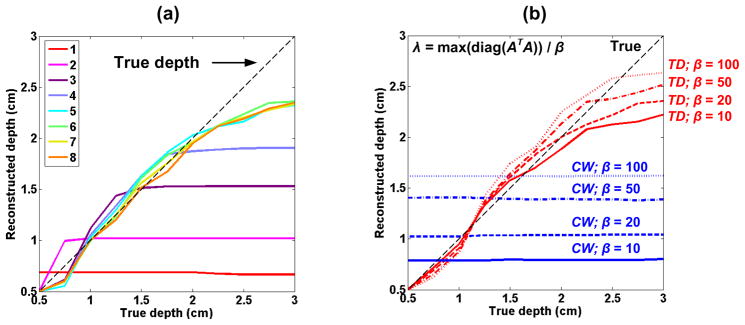

We studied the influence of the number of gates included in the reconstruction. Figure 4(a) shows the evolution of the reconstructed depth (depth of the COM) as a function of the true depth of an inclusion located at lateral position 1, for different number of gates included (starting from gate 1 on Fig. 1(c)). The reconstruction improves, more strikingly for deep inclusions, as more late gates are included, up to 6 gates, after which the reconstruction does not improve anymore as we include more noisy data. The first gate only brings minor improvement for superficial inclusion (data not shown), and does not contribute to the data reconstruction for deep inclusions. We tried other combinations (data not shown), and found that the best one with our parameters was 5 gates every 500 ps from 0.6 ns to 2.6 ns.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed depth of the COM as a function of the inclusion true depth, for a point-like inclusion in position 1, for (a) different delay gate combinations (β = 20), and (b) different threshold coefficients in the spatially varying regularization matrix L (gates 2 to 6 in Fig. 1(c)).

With these parameters, the inclusion can be reconstructed with a depth error under 15 % down to approximately 2.5 cm. The reconstructed depths of deeper inclusions continue to increase, but with larger errors, e.g. an inclusion at 3 cm is reconstructed at 2.3 cm (an underestimation of almost 25%).

3.4 Influence of the spatially varying regularization

By penalizing more the voxels with higher sensitivity, the L matrix enables us to reconstruct the inclusion better than a simple Tikhonov regularization [34]. However this matrix has to be thresholded so that regions far from a source-detector pair do not inappropriately receive larger weighting. The effect of this threshold is presented in Fig. 4(b), where the depth of the reconstructed COM is plotted vs. the true depth of the inclusion, for CW data and TD data with the 5-gate combination discussed above, and for a β factor of 10, 20, 50 and 100. With CW data, the absorption is reconstructed at a constant depth whatever its true depth, and this reconstructed depth simply increases as β increases. For TD data, a smaller threshold (large β) enables better reconstructions for deep inclusions (z > 2.5 cm), but also leads to an overestimated reconstructed depth for medium-deep inclusions (z around 1.5 to 2.5 cm). Moreover, for inclusions very close to the surface (under 1 cm) located just underneath a source or detector as in position 3 from Fig. 1(b), a large β also leads to strong artifacts (data not shown). A β = 20 was used in the following simulations, enabling a good compromise for reconstruction of different depths between 1 and 3 cm.

3.5 Influence of background optical properties

The evaluation of the baseline optical properties of a medium is subject to uncertainty [36]. Therefore, we tested the influence of an error in the background optical properties on the reconstruction. We do not present data for this study, but enunciate general results we observed. An overestimation of the scattering coefficient (μ′s,recon > μ′s,true) by 20% led to an inclusion being reconstructed closer to the surface by approximately 1 to 3 mm, and vice versa for an underestimation of the scattering coefficient. We did not observe an effect of an over- or under-estimated absorption coefficient (by up to 50%) on the reconstructed depth. For these results, the true depth of the inclusion was varied between 0.5 cm and 3 cm.

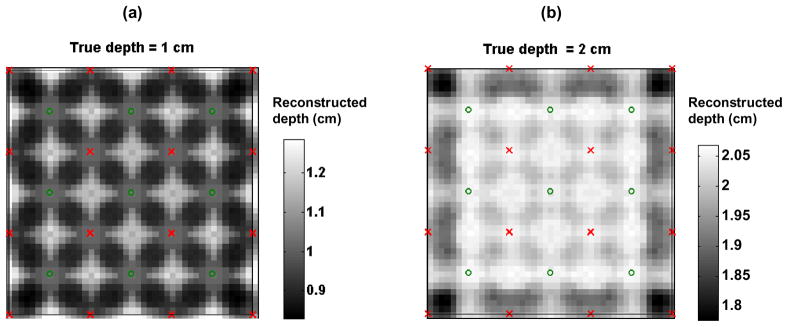

3.6 Variation of depth localization error with lateral position

One major advantage of TD data is the depth information provided by the time of flight of photons. In Fig. 4(a), we showed the evolution of the reconstructed depth as a function of the true depth for one particular lateral position. In Fig. 5, we present the evolution of the reconstructed depth as a function of the lateral position of the inclusion, for a 1 cm and 2 cm deep inclusion. In both cases, the depth error is small (within 20% at 1 cm, and about 5% away from the edges of the medium at 2 cm).

Fig. 5.

Depth of the COM for (a) a 1 cm deep and (b) a 2 cm deep inclusion reconstructed with TD data (5 gates) as a function of the inclusion lateral position.

For the inclusion located at 2cm below the surface, it also worth noting that the reconstructed depth varies very little with the lateral position of the inclusion. This means that the reconstruction method has no “blind zone”, and the depth reconstruction performance remains good for any position of the inclusion. Note that we do not compare the depth error with that obtained by CW measurements as no depth information is provided without overlapping or multi-distance CW measurement.

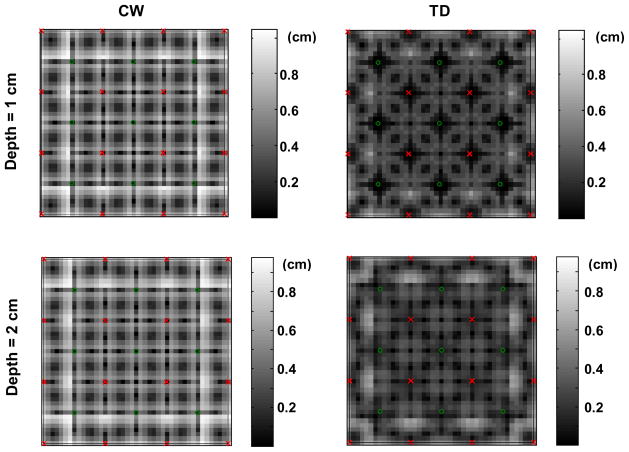

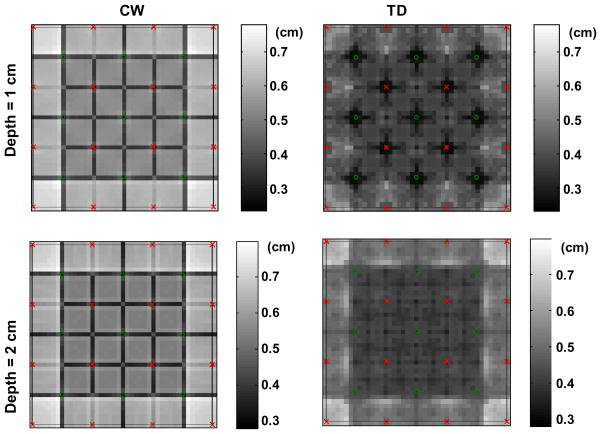

3.7 Lateral localization and resolution

In this section, we study the performance of the reconstruction method in terms of lateral localization and lateral resolution, and compare it with a CW reconstruction method. Figures 6 and 7 show the evolution of, respectively, the lateral localization error and the lateral resolution, for CW (left) and TD (right) reconstructions, at two different depths of the inclusion (1 cm, top, and 2 cm, bottom) as a function of the inclusion lateral position.

Fig. 6.

Lateral error (cm) for a 1 cm deep inclusion (top) and a 2 cm deep inclusion (bottom) reconstructed with CW (left) and TD (right) data, as a function of the inclusion lateral position.

Fig. 7.

Lateral resolution (cm) for a 1cm deep inclusion (top) and a 2 cm deep inclusion (bottom) reconstructed with CW (left) and TD (right) data, as a function of the inclusion lateral position.

For both depths, TD shows reduced error in the lateral localization and better lateral resolution. Importantly we also note that both the lateral resolution and the lateral localization for TD reconstructions are more uniform with the lateral position of the inclusion relative to the probe than with a CW reconstruction.

These improvements of TD over CW for the lateral localization and resolution can be explained intuitively based on the sensitivity profiles presented in Fig. 2. For later delay gates, the sensitivity profile of a given source-detector probes deeper into the medium giving us depth resolution, but also probes a larger region laterally providing additional information to improve lateral localization and resolution.

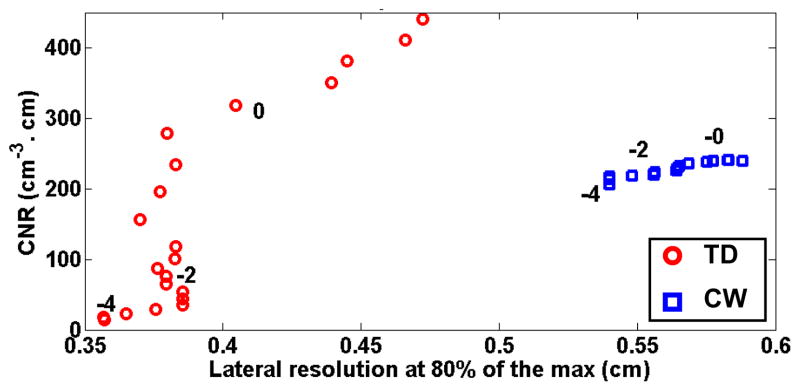

3.8 Contrast to noise ratio improvement

We have shown in a previous study [8] that CW and TD systems yield similar contrast to noise ratio (CNR) for typical depths of cerebral activation (1 to 2 cm) and source-detector separations (2 to 3 cm) used in functional brain imaging, with CW even giving slightly better CNR. The intuitive explanation of this result is the following: even though TD data yield better contrast to deep inclusion by selecting photons which have traveled deep inside the medium, these measurements are also impeded by a much higher noise due to the low level of light at late delays. However the CNR of an image has to be evaluated in regards to other metrics of the image, in particular its resolution.

In this section, we varied the regularization parameter α between 10−4 and 10, both for CW and TD reconstructions, and studied the evolution of CNR and lateral resolution. Figure 8 is a parametric curve of the image CNR as a function of the lateral resolution. The true inclusion is located at position 1, and at a depth z = 1.5 cm. We compute the CNR as the average contrast to noise ratio for all voxels of contrast above 80% of the maximum contrast. The image noise was obtained by propagation of the measurement noise by: σx2= pAinvσy2pAinvT, where σx2 is the image covariance matrix.

Fig. 8.

CNR versus lateral resolution for a regularization parameter α varying between 10−4 and 10. CNR is given per unit volume (cm3) and unit change in absorption (cm−1) of the inclusion. Regularization parameters of 1, 10−2 and 10−4 are indicated on the plot.

The plot illustrates the trade-off between CNR and resolution: as the regularization is increased, the CNR of the reconstructed inclusion increases, but is counter-balanced by a worsening of the lateral resolution. We observe that for an identical CNR of the image, the lateral resolution is improved by TD reconstructions compared to CW. Similarly, at identical lateral resolution, TD reconstruction enables a much higher CNR of the image.

4. Phantom reconstructions

4.1 TD instrument

Our TD system, based on a Ti: Sapphire pulsed laser and an intensified CCD camera acting as a parallel time-gated detector, has been described in previous publications [8,29]. At each detector position, we use a bundle of 7 fibers of different lengths by increment of 10 cm, enabling simultaneous detection in 7 delay gates by steps of 500 ps. For functional brain imaging, we developed a flexible probe consisting of a 4×4 array of sources and 3×3 array of detectors in a square geometry each, with a source-detector separation of 2.5 cm (same geometry as used for the above simulations and presented in Fig. 1(a)).

4.2 Phantom experiment

The system was tested on a liquid phantom containing a spherical absorbing inclusion. One half of the probe was set over a tank (19×19×9 cm3) filled with a solution of intralipid and ink (estimated optical properties: μa = 0.14 cm−1, μs′ = 10 cm−1), containing a hollow glass sphere of diameter 15 mm. The sphere was filled with the same intralipid solution with 70 times higher ink concentration. Images were acquired for 30 seconds with the sphere located at position 2 (as defined on Fig. 1(b)), followed by 30 seconds of acquisition with the sphere outside of the field of view of the probe. This procedure was repeated 5 times to increase signal to noise ratio. We repeated the experiment for three different depths of the inclusion: top of the sphere at a depth of 9.5 mm, 18.5 mm and 32.5 mm below the surface.

4.3 Phantom reconstructions

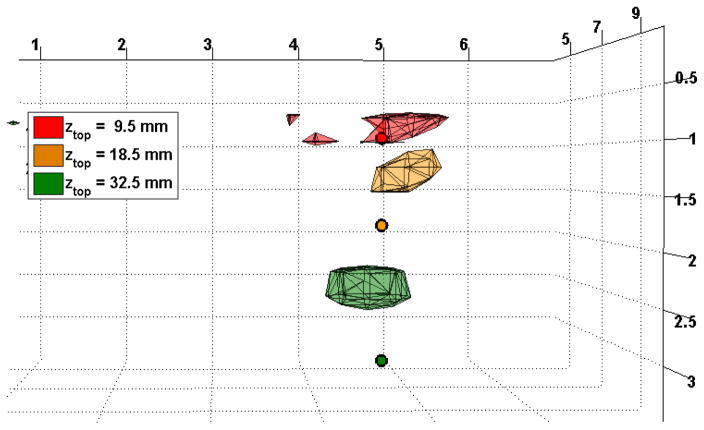

We calculated the contrast of the image as the percentage change in intensity between the “off” state when the sphere is outside of the field of view, and the “on” state when it is under the probe. We averaged the contrasts obtained from the 5 successive on/off states and used these data to reconstruct an image. We used a regularization parameter α = 10−2 for the first two depths of the sphere. However, for the deepest inclusion, the contrast to noise ratio was very low, and we had to change the regularization parameter to 10−1 to obtain a reasonable reconstruction. Figure 9 shows the reconstructions for all 3 depths of the inclusion, as well as the true position of the top of the absorbing sphere.

Fig. 9.

Phantom reconstruction for three different depths of the glass sphere. The rendered volumes show the contours at 80% of the maximum absorption contrast. The small circles represent the top of the 7.5 mm radius sphere.

The superficial inclusion is reconstructed at a depth of 7.5 mm, the second at a depth of 12.5 mm, and the deepest at 22.5 mm. In all cases the reconstruction is closer to the surface than the true inclusion, even for medium-deep inclusions, which differs from our simulations. Note that our simulations used a point absorption at a particular depth, while the experimental setup consists of a 15 mm diameter inclusion. Moreover our hypothesis of small perturbation breaks down as the solution in the glass sphere is strongly absorbing, hence the linear assumption is probably not valid anymore. In addition, we had to use a larger regularization parameter α than in the simulations because of the increased noise level of the experimental data. The effect of a higher regularization parameter is also to pull the reconstruction towards the surface (simulation data not shown). However, the formalism developed here enables reconstruction of experimental differential data at three different depths down to 3 cm of the true inclusion.

5. Conclusion

We presented a 3D reconstruction technique of differential TD gated data, and showed with simulated data that the method allows both depth resolution and improved lateral resolution and lateral localization compared to traditional CW reconstruction. With our typical experimental parameters, we also showed that only a limited number of gates is useful for optimal image reconstruction. The technique was used to reconstructed dynamic phantom images, where a spherical absorbing inclusion was embedded at various depths within a scattering intralipid solution. The technique presented here for gated measurements would be easily adaptable to moments of TPSF, provided that careful treatment of the covariance matrix is used in the reconstruction regularization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anand Kumar for useful discussions on the spatially varying regularization. This work was supported by the NIH grants P41-RR14075, R01-EB002482 and NIBIB-EB00790.

References and links

- 1.Obrig H, Villringer A. Beyond the visible – imaging the human brain with light. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;23:1–18. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000043472.45775.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson AP, Hebden JC, Arridge SR. Recent advances in diffuse optical imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:R1–R43. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/4/r01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Special section on Optics in Neuroscience. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson MS, Chance B, Wilson BC. Time-resolved reflectance and transmittance for the non-invasive measurement of tissue optical properties. Appl Opt. 1989;28:2331–36. doi: 10.1364/AO.28.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ntziachristos V, Ma XH, Yodh AG, Chance B. Multichannel photon counting instrument for spatially resolved near infrared spectroscopy. Rev Sci Instrum. 1999;70:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbrink J, Wabnitz H, Obrig H, Villringer A, Rinneberg H. Determining changes in NIR absorption using a layered model of the human head. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46:879–896. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/3/320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torricelli A, Pifferi A, Spinelli L, Cubeddu R, Martelli F, Del Bianco S, Zaccanti G. Time-resolved reflectance at null source-detector separation: improving contrast and resolution in diffuse optical imaging. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(078101):1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.078101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selb J, Stott JJ, Franceschini MA, Sorenson AG, Boas DA. Improved sensitivity to cerebral dynamics during brain activation with a time-gated optical system: analytical model and experimental validation. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:011013. doi: 10.1117/1.1852553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montcel B, Chabrier R, Poulet P. Detection of cortical activation with time-resolved diffuse optical methods. Appl Opt. 2005;44:1942–1947. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.001942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eda H, Oda I, Ito Y, Wada Y, Oikawa Y, Tsunazawa Y, Takada M, Tsuchiya Y, Yamashita Y, Oda M, Sassaroli A, Yamada Y, Tamura M. Multichannel time-resolved optical tomographic imaging system. Rev Sci Instrum. 1999;70:3595–3602. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartling J, Dam JS, Andersson-Engels S. Comparison of spatially and temporally resolved diffuse-reflectance measurements systems for determination of biomedical optical properties. Appl Opt. 2003;42:4612–4620. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.004612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweiger M, Arridge SR. Application of temporal filters to time resolved data in optical tomography. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:1699–1717. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/7/310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao F, Tanikawa Y, Zhao H, Yamada Y. Semi-three-dimensional algorithm for time-resolved diffuse optical tomography by use of the generalized pulse spectrum technique. Appl Opt. 2002;41:7346–7358. doi: 10.1364/ao.41.007346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebert A, Wabnitz H, Grosenick D, Möller M, Macdonald R, Rinneberg H. Evaluation of optical properties of highly scattering media by moments of distributions of times of flight of photons. Appl Opt. 2003;42:5785–5790. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.005785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kienle A, Glanzmann T, Wagnières G, van den Bergh H. Investigation of two-layered turbid media with time-resolved reflectance. Appl Opt. 1998;37:6852–6862. doi: 10.1364/ao.37.006852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martelli F, Del Bianco S, Zaccanti G, Pifferi A, Toricelli A, Bassi A, Taroni P, Cubeddu R. Phantom validation and in vivo application of an inversion procedure for retrieving the optical properties of diffusive layered media from time-resolved reflectance measurements. Opt Lett. 2004;29 doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett AH, Culver JP, Sorensen AG, Dale A, Boas DA. Robust inference of baseline optical properties of the human head with three-dimensional segmentation from magnetic resonance imaging. Appl Opt. 2003;42:3095–3108. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.003095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hintz SR, Benaron DA, van Houten JP, Duckworth JL, Liu FWH, Spilman SD, Stevenson DK, Cheong WF. Stationary headband for clinical time-of-flight optical imaging at the bedside. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;68:361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebden JC, Gibson A, Yusof R, Everdell N, Hillman EMC, Delpy DT, Arridge SR, Austin T, Meek JH, Wyatt JS. Three-dimensional optical tomography of the premature infant brain. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:4155–4166. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/23/303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maki A, Yamashita Y, Ito Y, Watanabe E, Mayanagi Y, Koizumi H. Spatial and temporal analysis of human motor activity using noninvasive NIR topography. Med Phys. 1995;22:1997–2005. doi: 10.1118/1.597496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gratton G, Corballis PM, Cho E, Fabiani M, Hood DC. Shades of gray matter: noninvasive optical images of human brain responses during visual stimulation. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:505–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franceschini MA, Toronov V, Filiaci M, Gratton E, Fantini S. On-line optical imaging of the human brain with 160 ms temporal resolution. Opt Express. 2000;6:49–57. doi: 10.1364/oe.6.000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boas DA, Gaudette TJ, Strangman G, Cheng X, Marota JJA, Mandeville JB. The accuracy of near infrared spectroscopy and imaging during focal changes in cerebral hemodynamics. Neuroimage. 2001;13:76–90. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delpy DT, Cope M, van der Zee P, Arridge S, Wray S, Wyatt J. Estimation of optical pathlength through tissue from direct time of flight measurement. Phys Med Biol. 1988;33:1433–1442. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/33/12/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraoka M, Firbank M, Essenpreis M, Cope M, Arridge SR, van der Zee P, Delpy DT. A Monte Carlo investigation of optical pathlength in inhomogeneous tissue and its application to near-infrared spectroscopy. Phys Med Biol. 1993;38:1859–1876. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/38/12/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebert A, Wabnitz H, Steinbrink J, Obrig H, Möller M, Macdonald R, Villringer A, Rinneberg H. Time-resolved multidistance near-infrared spectroscopy of the adult head: intracerebral and extracerebral absorption changes from moments of distribution of times of flight of photons. Appl Opt. 2004;43:3037–3047. doi: 10.1364/ao.43.003037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liebert A, Wabnitz H, Steinbrink J, Möller M, Macdonald R, Rinneberg H, Villringer A, Obrig H. Bed-side assessment of cerebral perfusion in stroke patients based on optical monitoring of a dye-bolus by time-resolved diffuse reflectance. Neuroimage. 2005;24:426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kacprzak M, Liebert A, Sawosz P, Zolek N, Maniewski R. Time-resolved optical imager for assessment of cerebral oxygenation. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034019. doi: 10.1117/1.2743964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boas DA, Chen K, Grebert D, Franceschini MA. Improving the diffuse optical imaging spatial resolution of the cerebral hemodynamic response to brain activation in humans. Opt Lett. 2004;29:1506–1508. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selb J, Joseph DK, Boas DA. Time-gated optical system for depth-resolved functional brain imaging. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:044008. doi: 10.1117/1.2337320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haskell RC, Svaasand LO, Tsay TT, Feng TC, McAdams MS, Tromberg BJ. Boundary conditions for the diffusion equation in radiative transfer. J Opt Soc Am A. 1994;11:2727–2741. doi: 10.1364/josaa.11.002727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arridge SR. Photon-measurement density functions. Part I: Analytical forms. Appl Opt. 1995;34:7395–7409. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.007395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carraresi S, Shatir TSM, Martelli F, Zaccanti G. Accuracy of a perturbation model to predict the effect of scattering and absorbing inhomogeneities on photon migration. Appl Opt. 2001;40:4622–4632. doi: 10.1364/ao.40.004622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Culver JP, Siegel AM, Stott JJ, Boas DA. Volumetric diffuse optical tomography of brain activity. Opt Lett. 2003;28:2061–2063. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.002061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boas DA, Dale AM. Simulation study of magnetic resonance imaging-guided cortically constrained diffuse optical tomography of the human brain function. Appl Opt. 2005;44:1957–1968. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.001957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comelli D, Bassi A, Pifferi A, Taroni P, Torricelli A, Cubeddu R, Martelli F, Zaccanti G. In vivo time-resolved reflectance spectroscopy of the human forehead. Appl Opt. 2007;46:1717–1725. doi: 10.1364/ao.46.001717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao F, Zhao H, Tanikawa Y, Yamada Y. Optical tomographic mapping of cerebral haemodynamics by means of time-domain detection: methodology and phantom validation. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:1055–1078. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/6/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]