Abstract

CDK11p58, a member of the p34cdc2-related kinase family, is associated with cell cycle progression, tumorigenesis, and proapoptotic signaling. It is also required for the maintenance of chromosome cohesion, the maturation of centrosome, the formation of bipolar spindle, and the completion of mitosis. Here we identified that CDK11p58 interacted with itself to form homodimers in cells, whereas D224N, the kinase-dead mutant, failed to form homodimers. CDK11p58 was autophosphorylated, and the main functions of CDK11p58, such as kinase activity, transactivation of nuclear receptors, and proapoptotic signal transduction, were dependent on its autophosphorylation. Furthermore, the in vitro kinase assay indicated that CDK11p58 was autophosphorylated at Thr-370. By mutagenesis, we created CDK11p58 T370A and CDK11p58 T370D, which mimic the dephosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of CDK11p58, respectively. The T370A mutant could not form dimers and be phosphorylated by the wild type CDK11p58 and finally lost the kinase activity. Further functional research revealed that T370A failed to repress the transactivition of androgen receptor and enhance the cell apoptosis. Overall, our data indicated that Thr-370 is responsible for the autophosphorylation, dimerization, and kinase activity of CDK11p58. Moreover, Thr-370 mutants might affect CDK11p58-mediated signaling pathways.

Keywords: Apoptosis, CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Protein Cross-linking, Protein Kinases, Transcription Regulation, CDK11p58, Autophosphorylation, Dimerization, Kinase Activity

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase 11 (the PITSLRE protein kinases) are closely related to cell cycle regulation, oncogenesis, and apoptosis in a kinase-dependent manner (1–4). To date, at least 10 CDK11 isoforms have been cloned from eukaryotic cells, with their molecular masses varying from 46 to 110 kDa (3). CDK11p58 is translated from a single transcript as CDK11p110 by initiation at an alternative in-frame AUG codon (5, 6). CDK11p58 kinase is essential for cell viability as well as normal early embryonic development (7).

CDK11p58 contains a conserved p34cdc2-related Ser/Thr protein kinase catalytic domain (amino acids 80–389) and N-terminal (amino acids 1–79) and C-terminal (amino acids 390–439) regions in its structure (1). Although CDK11p58 shares the same sequence, including the kinase domain, as the C terminus of CDK11p110, the two isoforms possess different functions. CDK11p110 is present at a constant level during the cell cycle and is involved in pre-RNA splicing and the regulation of RNA transcription (2). In contrast, CDK11p58 is specifically expressed in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and closely related to G2/M arrest and apoptosis in a kinase-dependent manner (1, 3, 4, 8, 9). Ectopic expression of CDK11p58 in Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts results in prolonged late telophase, abnormal chromosome segregation, and decreased cell growth rates due to apoptosis (10). CDK11p58 also promotes centrosome maturation and bipolar spindle formation (11). Recent studies revealed that CDK11p58 is essential for the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion and regulation of androgen receptor (AR)3 activity (12).

Previous researches have indicated that CDK11p58 and its larger isoforms may function as effectors in the apoptotic signaling pathway(s), which is mediated through a 50-kDa isoform, CDK11p50, generated by caspase cleavage of the larger isoforms, including CDK11p58 and CDK11p110 (3, 6, 7, 9). During Fas-mediated cell death and apoptosis induced by glucocorticoids, CDK11p58 can be cleaved within the N-terminal domain of the protein by multiple caspases (1, 3). We have shown that CDK11p58 enhanced the apoptosis induced by cycloheximide in SMMC-7721 hepatocarcinoma cells (10). CDK11p58 down-regulates Bcl-2 during the proapoptotic pathway, depending on its kinase activity (13). As a cyclin-dependent kinase, CDK11p58 interacts with cyclin D3 to regulate G2/M phase cell cycle progression (14) and represses AR-mediated transactivation through phosphorylating AR to inhibit androgen-dependent proliferation of prostate cancer cells (15). CDK11p58 is also involved in the negative regulation of estrogen receptor and vitamin D3 receptor, the other two nuclear transcription factors (16, 17).

Previous work indicates that the kinase activation and phosphorylation process of kinase protein has a key relationship with its dimerization. Protein kinase autophosphorylation of activation segment residues is a common regulatory mechanism in phosphorylation-dependent signaling cascades. For example, the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which belongs to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, can be autophosphorylated/autoactivated, which is a consequence following homodimerization of the kinase (18). MTK1 (also called MEKK4) is a stress-responsive MAPKKK. Its N terminus is capable of binding to its C-terminal segment to inhibit the C-terminal kinase domain. The stress-inducible GADD45 family binding induces MTK1 N-C dissociation, dimerization, and autophosphorylation at Thr-1493, leading to the activation of the kinase catalytic domain (19). The antiviral protein kinase PKR catalytic domain dimerization triggers autophosphorylation at Thr-446, and phosphorylates eIF2 to inhibit protein synthesis (20).

Although CDK11p58 plays important roles in cellular events, little is known about the basis of its functions, such as its protein structure and the regulation of its kinase activity. This report, it shows that the dimerization and autophosphorylation of CDK11p58 at Thr-370 are essential for the activation of CDK11p58-mediated signaling pathways. These data may contribute to a better understanding of the molecular mechanism of CDK11 activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Reagents

Leupeptin, aprotinin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma. Protein G-agarose, histone H1, and polyvinylidene difluoride membrane were purchased from Roche Applied Science. Restriction enzymes, bovine calf serum, DMEM, TRIzol reagent, Lipofectamine reagent, and the expression vectors pcDNA3.0 and pcDNA3.1 were purchased from Invitrogen. Mouse anti-HA, mouse anti-GAPDH, and rat normal IgG antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). PGL3-Basic was from Promega. The anti-HA Ab, anti-Myc Ab, anti-GAPDH Ab, rabbit polyclonal anti-PITSLRE (C-17), and anti-His were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) was purchased from Pierce. Phosphoserine antibody and phosphothreonine antibody were from Sigma. The dual luciferase reporter assay system was bought from Promega. The ECL assay kit and [γ-32P]ATP (>3,000 Ci/mm) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences.

Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis

The point mutants of CDK11p58 were amplified twice by PCR from HA-CDK11p58 and inserted into EcoRI/XhoI sites of pcDNA3.1A/Myc-His and pcDNA3.0/HA. The primers were as follows: CDK11p58 (5′-CCGAATTCATGAGTGAAGATGAAG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTCAGAACTTGAGGCTGAA-3′), CDK11p58 T39A (5′-CCGAATTCATGAGTGAAGATGAAG-3′ and 5′-TGCGGCGCTCCCTCACCCACTTCTT-3′), CDK11p58 S54A (5′-CCGACGCCCCTGCCCTGGCGCCCAT-3′ and 5′-AGGGCAGGGGCGTCGGGCACATAGT-3′), CDK11p58 S58A (5′-CCGAATTCATGAGTGAAGATGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTGAGCTCGATGGGCGCCAGGGCA-3′), CDK11p58 S233A (5′-GGAGCCCCTCTGAAGGCCTACGCCC-3′ and 5′-GGGGCGTAGGCCTTCAGAGGGGCTC-3′), CDK11p58 T239A (5′-TACGCCCCGGTCGTGGTGACCCTGT-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTCAGAACTTGAGGCTGAA-3′), CDK11p58 T300A (5′-TCTGGGGGCCCCTAGTGAGAAAATC-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTCAGAACTTGAGGCTGAA-3′), CDK11p58 T370A (5′-ATTTCCGCGAGGCCCCCCTCCCCAT-3′ and 5′-ATGGGGAGGGGGGCCTCGCGGAAAT-3′), CDK11p58 T370D (5′-ATTTCCGCGAGGACCCCCTCCCCAT-3′ and 5′-ATGGGGAGGGGGTCCTCGCGGAAAT-3′), and CDK11p58 S396A (5′-TGTGAAGCGGGGCACCGCCCCGAGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTCAGAACTTGAGGCTGAA-3′).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Synchronization

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator (5% CO2, 95% air). Cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To block cells in the G2/M phase, cells were treated with 10 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h, and then cells were harvested and experiments were performed.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

HeLa cells were transfected with 4 μg of HA-CDK11p58 and 4 μg of Myc-CDK11p58 plasmids in 100-mm plates. Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and solubilized with 1 ml of coimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 15 mm MgCl2, 60 mm β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 mm NaF, 0.1 mm benzamide, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mm PMSF). Detergent-insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation. Cell lysates were incubated with 2 μg of relevant antibody at 4 °C for 2 h. Pre-equilibrated protein G-agarose beads were added and collected by centrifugation after incubation overnight and then gently washed three times with the lysis buffer. The bound proteins were eluted and analyzed using Western blots. An antibody to GAPDH was used to ensure equivalent loading.

GST Pull-down Assay

GST-CDK11p58, GST-K111N, and GST-D224N were purified from bacterial lysates using glutathione-agarose beads (Amersham Biosciences). His-CDK11p58, His-K111N and His-D224N proteins were purified from Escherichia coli using high performance nickel-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). 20 μl of His-tagged proteins were incubated with 5 μl (about 10 μg) of GST-tagged fusion protein or control protein (GST) in 300 μl of lysis buffer and rotated for 3–5 h at 4 °C. Pre-equilibrated glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were added and collected by centrifugation after incubation overnight and then gently washed three times with the lysis buffer. The beads were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and analyzed by Western blot.

Cross-linking Assay

HeLa cells were transfected with 4 μg of HA-CDK11p58 or 4 μg of HA-D224N in 100-mm plates. Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (20 nm sodium phosphate, 0.15 m NaCl, pH 8.0). DSS solution was added to a final concentration of 4 mm. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then added with the Quench Solution (1 m Tris, pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 20 mm. The quench reaction was performed at room temperature for 15 min. After cross-linking, the proteins were collected by centrifugation, boiled in 1× SDS sample buffer, and analyzed with Western blots. Additionally, purified His-tagged protein samples were cross-linked with DSS, and the cross-linked products were directly resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Gel Filtration Chromatography

Purified His-tagged CDK11p58 proteins were subjected to analytical gel filtration using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline. 1-ml fractions were collected in the same buffer, and the protein concentrations were determined by measuring A280 nm. Relevant fractions were condensed and used to analyze their kinase activity. Column calibration was performed using appropriate molecular weight standards (lactate dehydrogenase, BSA, and bovine carbonic anhydrase).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

The CDK11p58 protein kinase activity assay was carried out as described previously with minor modifications. After transfection with 4 μg of CDK11p58 or its mutants, 500 μg of HeLa cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. The protein kinase activity of the immunoprecipitates was assayed in 30 μl of kinase buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 15 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 50 μm ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP) containing 1 μg of histone H1 or purified CDK11p58 mutants or without. After incubation at 30 °C for 30 min, reactions were terminated by the addition of 5× SDS sample buffer. The samples were centrifuged after denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min. The supernatants were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was fixed, dried, and analyzed by the FLA-5100 phosphorimaging system (Fujifilm). Radioactive kinase assays of the fusion protein were conducted in a similar manner.

Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays

HeLa cells were cotransfected with AR (20 ng), an MMTV luciferase reporter construct (200 ng), a control Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL) (2 ng), and CDK11p58. Total DNA was adjusted to 500 ng with empty pcDNA vector. At 16 h posttransfection, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing ethanol (EtOH) or 10 nm dihydrotestosterone. After a further 24 h, a dual luciferase reporter gene assay (Promega) was performed as reported previously (15) using a Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (EG&G Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Analysis of Apoptosis by Flow Cytometry

Adherent and non-adherent cells were collected, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol for at least 1 h. The fixed cells were washed and stained with propidium iodide mixture containing 50 μg/ml propidium iodide, 0.05% Triton X-100, 37 μg/ml EDTA, and 100 units/ml ribonuclease in PBS. After incubation for 45 min at 37 °C, the DNA content was determined by quantitative flow cytometry with standard optics with a FACScan flow cytometer (FACStar, BD Biosciences). The percentage of apoptosis was quantitated from sub-G1 events.

RESULTS

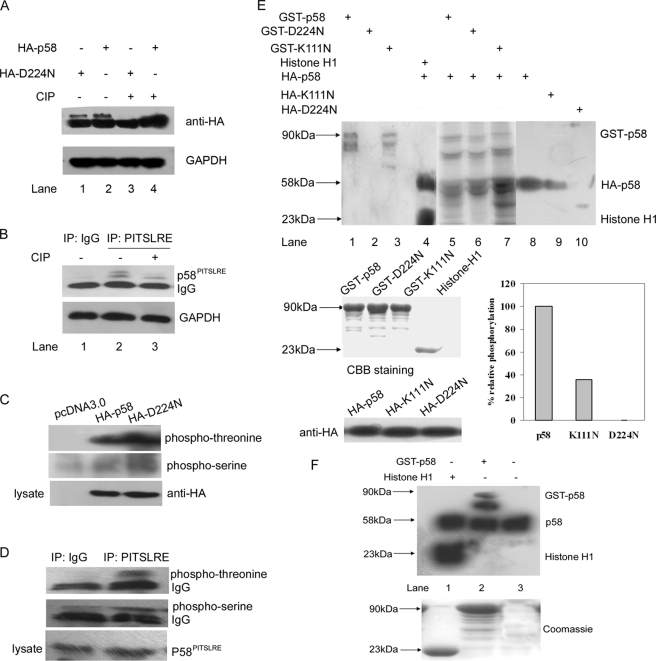

CDK11p58 Is Autophosphorylated in Vitro

Western blot using CDK11p58-transfected HeLa cell lysates and anti-PITSLRE polyclonal antibody showed that there were two close bands around 58–60 kDa. We asked whether the dual bands were due to the phosphorylation of CDK11p58 in cells. To clarify that, the intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) was used. HeLa cells were transfected with CDK11p58 or its kinase-dead mutant D224N, lysed with IP buffer, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-PITSLRE antibody. The precipitated proteins were incubated with CIP at 37 °C for 1 h. After CIP treatment, the top brands disappeared (Fig. 1A). These results suggested that the protein CDK11p58 and its kinase-dead mutant D224N were phosphorylated in the cells. Then the phosphorylation of the endogenous CDK11p58 was tested. HeLa cells were arrested in G2/M phase with nocodazole and then immunoprecipitated with anti-PITSLRE antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were dephosphorylated by CIP and subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-PITSLRE antibody. We could also find that the top brands disappeared after CIP treatment. Considering that CDK11p58 is a Ser/Thr kinase, we explored whether it was autophosphorylated. HeLa cells were transfected with HA-CDK11p58 or HA-D224N. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-PITSLRE antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-phosphothreonine and anti-phosphoserine antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1C, CDK11p58 and D224N were predominantly phosphorylated at threonine(s) (compare lane 1 and lanes 2 and 3). Similar results were obtained when detecting the phosphorylation of the endogenous CDK11p58 (Fig. 1D). To examine whether CDK11p58 was autophosphorylated, HA-tagged CDK11p58 was transfected into HeLa cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Recombinant CDK11p58, K111N (which still has minor kinase activity), and D224N proteins were bacterially expressed as GST fusion proteins and used as substrates in the in vitro kinase assay. Histone H1 was used as a positive control (21). As shown in Fig. 1E, these proteins were all phosphorylated in vitro by the wild type CDK11p58. Additionally, we simply immunoprecipitated HA-CDK11p58 and D224N and K111N mutants and quantified their respective autophosphorylations without exogenous substrate. The autophosphorylation level of CDK11p58 was 2.7-fold relative to that of K111N (Fig. 1E). GST-CDK11p58 could also be phosphorylated by the internal CDK11p58 protein (Fig. 1F). These data suggested that CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated in cells.

FIGURE 1.

CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated in vitro. A, CDK11p58 was dephosphorylated with CIP. HeLa cells were transfected with 4 μg of HA-CDK11p58 or HA-D224N. At 48 h after transfection, cells were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-PITSLRE (C-17) polyclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were predephosphorylated by CIP (only for lanes 3 and 4, indicated with a plus sign) or directly subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-HA antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.). B, to block cells in G2/M phase, HeLa cells were treated with 10 ng/ml nocodazole for 16 h, and then cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with 2 μg of anti-PITSLRE (C-17) polyclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were predephosphorylated by CIP (only for lane 3) or directly subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-PITSLRE (C-17) antibody. C, CDK11p58 was serine/threonine-phosphorylated. HeLa cells were transfected with 4 μg of HA-CDK11p58 or HA-D224N. At 48 h after transfection, cells were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-HA monoclonal antibody. The proteins were subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibody. D, HeLa cells were synchronized as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-PITSLRE (C-17) polyclonal antibody. The proteins were subjected to Western blot and probed with anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibody. E, CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated in vitro. HA-CDK11p58, HA-K111N, and HA-D224N were transfected into HeLa cells separately. At 48 h posttransfection, lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Substrates included or did not include bacterially expressed and purified proteins. The supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging. Histone H1 was employed as a positive control. Purified substrates were Coomassie staining and expression levels of HA-CDK11p58 wild type and its mutants was used as a control. Relative phosphorylation activities of p58, D224N, and K111N without exogenous substrate are presented as percentages where kinase activity of HA-p58 precipitates is arbitrarily set at 100%. F, HeLa cells were synchronized as in B. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-PITSLRE (C-17) antibody. Bacterially expressed and purified CDK11p58 were used as substrates. The supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging. Histone H1 was employed as a positive control.

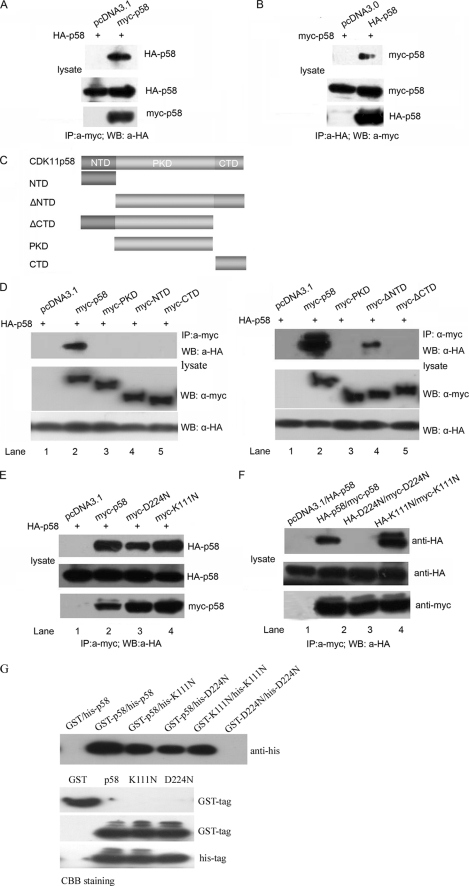

CDK11p58 Interacts with Itself in Vivo and in Vitro

CDK11p58 homointeraction was investigated to provide the structural basis for the autophosphorylation of CDK11p58. HA-CDK11p58 was co-transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector or Myc-CDK11p58 into HeLa cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibody. HA-CDK11p58 was present in the immunoprecipitates using anti-Myc antibody from cells co-transfected with HA- and Myc-CDK11p58 but not from cells co-transfected with HA-CDK11p58 and pcDNA3.1-Myc vector (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, HeLa cells were co-transfected with constructs expressing Myc-CDK11p58 and HA-CDK11p58 or pcDNA3-HA vector. Immunoprecipitation indicated that Myc-CDK11p58 was present in the immunoprecipitates from HA- and Myc-CDK11p58-cotransfected HeLa cells but was absent in the immunoprecipitates from Myc-CDK11p58- and pcDNA3-HA vector-co-transfected cells (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

CDK11p58 interacts with itself in vivo and in vitro. A, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.0-HA-CDK11p58 or combinations of pcDNA3.0-Myc-CDK11p58, respectively. 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested, and the lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-Myc antibody, followed by Western blot analysis (WB) with an anti-HA antibody. 10% whole cell lysate (WCL) was probed for the expression of p58. The HA-p58 from immunoprecipitation and whole cell lysate was quantitated, and the ratio of HA-p58 binding to Myc-p58 was determined. B, HeLa cells were transfected as in A. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA, and the co-precipitated CDK11p58 was detected with an anti-Myc antibody by Western blot analysis. All of the results were representative of three independent experiments. 10% whole cell lysate was probed for the expression of p58. C, schematic representation of CDK11p58 domains. NTD, N-terminal domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; PKD, Ser/Thr protein kinase domain. ΔNTD, N-terminal domain-deleted mutant; ΔCTD, C-terminal domain-deleted mutant. D, co-immunoprecipitation of CDK11p58 with different CDK11p58 domains. HeLa cells were transfected with HA-CDK11p58 and Myc-tagged deletion mutants or the pcDNA3.1-Myc vector. Left, HA-p58 interaction with Myc-p58, Myc-PKD, Myc-NTD, and Myc-CTD. Right, HA-p58 interaction with Myc-p58, Myc-PKD, Myc-ΔNTD, and Myc-ΔCTD. 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed with 1× immunoprecipitation buffer and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody. The precipitants were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blot with an anti-HA antibody. 10% whole cell lysate was probed for the expressions of the deletion mutants. E, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the indicated combinations of pcDNA3.0-HA-CDK11p58 expression constructs, respectively. The co-immunoprecipitation assay was done as in A. F, HeLa cells were transfected with the combination of HA-p58 and Myc-CDK11p58, the combination of HA-D224N and Myc-D224N, or the combination of HA-K111N and Myc-K111N. The co-immunoprecipitation assay was carried out as in A. G, 20 μl of His-tagged p58, K111N, and D224N proteins were incubated with 5 μl of GST-tagged fusion protein or control protein (GST) in lysis buffer and rotated for 3–5 h at 4 °C. Pre-equilibrated glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were added and collected by centrifugation after incubation overnight and then gently washed three times with the lysis buffer. Proteins bound to the beads were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by Western blot. Protein loading of CDK11p58 and its mutants were determined by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB).

CDK11p58 contains a C-terminal conserved p34cdc2-related Ser/Thr protein kinase catalytic domain and an N-terminal unique putative calmodulin-binding site (1). In order to characterize the specific interaction domain of CDK11p58, five truncated fragments of CDK11p58 were constructed (Fig. 2C). The immunoprecipitation assay showed that ΔNTD was the minimal deletion to interact with CDK11p58 (Fig. 2D). D224N, the kinase-dead mutant of CDK11p58, was still able to bind the wild type CDK11p58. Interestingly, D224N homointeraction was not observed in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 2, E–G). These data suggested that the homointeraction of CDK11p58 was related to its kinase activity.

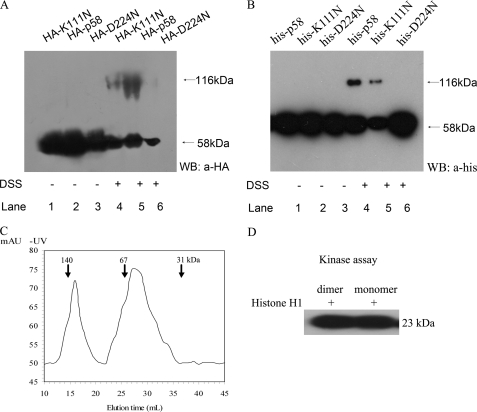

CDK11p58 Dimerization and Kinase Activity

To examine whether the CDK11p58 protein undergoes dimerization, a protein cross-linking assay was performed using the cross-linker DSS. Western blotting using the lysates prepared from transfected cells without phosphatase inhibitors showed only one band at ∼58 kDa representing CDK11p58 monomer (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–3). HA-CDK11p58 and HA-K111N dimers (∼116 kDa) were detected following DSS treatment (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). Nevertheless, dimers of the kinase-dead mutant HA-D224N were not observed in DSS-treated cell lysates (Fig. 3A, lane 6). The purified proteins, His-tagged CDK11p58 and its K111N and D224N mutants were also subject to the protein cross-linking assay and drew a similar result (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the coimmunoprecipitation data, these results suggested that the wild type CDK11p58 can dimerize in vivo and in vitro, and the process was associated with its kinase activity.

FIGURE 3.

CDK11p58 dimerization and kinase activity. A, HA-CDK11p58, HA-D224N, or HA-K111N were separately transfected in HeLa cells. 48 h after transfection, cells were washed and incubated with the cross-linker DSS. The samples were analyzed by anti-HA antibody (a-HA) using Western blots (WB). B, purified His-tagged CDK11p58, D224N, and K111N were incubated with the cross-linker DSS. The samples were analyzed by anti-His antibody. C, gel filtration of wild type p58. Wild type p58 was applied to a Superdex 200 gel filtration column. 1-ml fractions were collected, and the A280 nm value was measured. The elution position of molecular mass standards (in kDa) are marked with arrows. D, 1-ml fractions (dimeric or monomeric p58) were condensed to analyze their kinase activity.

Size exclusion gel filtration chromatography was used to further analyze the kinase activity of dimeric and monomeric CDK11p58. Column calibration was performed using appropriate molecular weight standards. Gel filtration of recombinant wild type CDK11p58 resulted in two distinct peaks at 16 and 27 ml, which represented dimeric or monomeric form (Fig. 3C). The in vitro kinase assay showed that the kinase activity of dimeric and monomeric CDK11p58 made no difference (Fig. 3D).

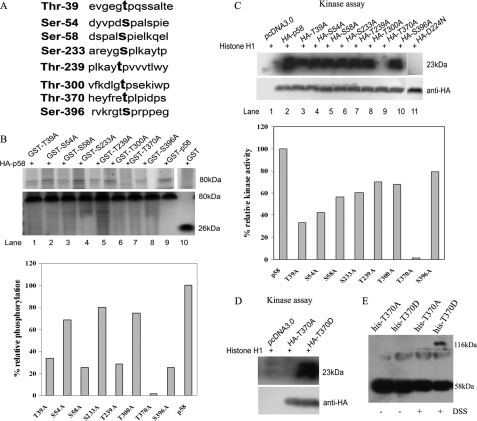

Mutation of CDK11p58 Thr-370 to Alanine Inhibits the Autophosphorylation and Dimerization and Eliminates the Kinase Activity of CDK11p58

Given the fact that CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated in vitro, we herein investigated the exact phosphorylation site(s). CDK11p58 protein contains eight potential consensus Ser/Thr-Pro CDK phosphorylation sites: Thr-39, Ser-54, Ser-58, Ser-233, Thr-239, Thr-300, Thr-370, and Ser-396 (Fig. 4A). CDK11p58 point mutants were generated by replacing Ser/Thr with Ala individually, constructed into pGEX-4T-1 vector, expressed in E. coli, purified, and employed as substrates for the in vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated wild type CDK11p58 from transfected cells. We found that among these mutants, T370A was poorly phosphorylated in vitro (Fig. 4B, lane 7), whereas the other mutants were phosphorylated by HA-CDK11p58 with similar efficiency as the wild type CDK11p58 (Fig. 4B, lanes 1-6 and 8 versus lane 9). Combined with the previous finding that CDK11p58 was phosphorylated at threonine(s), it therefore suggested that Thr-370 was the autophosphorylation site of CDK11p58. Furthermore, we asked whether phosphorylation of CDK11p58 at Thr-370 affects its kinase activity. It was shown that histone H1 was not phosphorylated by the T370A mutant, a similar pattern as for the kinase-dead mutant D224N (Fig. 4C). However, histone H1 was phosphorylated by T370D in the in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4D). These data provide evidence that phosphorylation of CDK11p58 at Thr-370 contributes to the activation of this kinase. To further determine whether the loss of autophosphorylation and kinase activity correlated with an inability to dimerize, we analyzed T370A and T370D mutants using the aforementioned cross-linking assay. We observed that “autophosphorylation-inactive” mutant T370A existed mainly as a monomer and could not form the 116-kDa dimer (Fig. 4E). Consistently, T370D mutant that retained the ability to autophosphorylate was identified to form a dimer with cross-linker. These findings, taken together with the Thr-370 mutant data, suggest that CDK11p58 autophosphorylation is required for dimerization, and the Thr-370 site plays an important role in dimerization.

FIGURE 4.

Mutation of CDK11p58 Thr-370 to alanine inhibits the autophosphorylation and dimerization and eliminates the kinase activity of CDK11p58. A, eight putative phosphorylation sites within CDK11p58. B, wild type CDK11p58 and its mutants CDK11p58 T39A, S54A, S58A, S233A, T239A, T300A, T370A, and S396A were bacterially expressed and purified. HA-CDK11p58 was immunoprecipitated from transfected HeLa cells. In vitro kinase assays were performed as described above. Purified substrates with Coomassie staining were used as controls. Relative phosphorylation of purified GST-tagged proteins is presented as a percentage, where the phosphorylated level of GST-p58 is arbitrarily set at 100%. C, HA-CDK11p58 and its mutants were transfected into HeLa cells. At 48 h posttransfection, lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Histone H1 was used as substrate for the in vitro kinase assay. The supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging. The lower panel shows the expression levels of several proteins indicated. Relative kinase activities of wild type p58 and its mutants are presented as percentages, where the kinase activity of HA-p58 precipitates is arbitrarily set at 100%. D, HA-T370A and HA-370D were immunoprecipitated from transfected HeLa cells, and histone H1 was used as substrate. In vitro kinase assays were performed as described above. E, cross-linking analysis of purified Thr-370 mutants. Proteins were incubated with the cross-linker DSS. The samples were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and then detected with anti-His antibody.

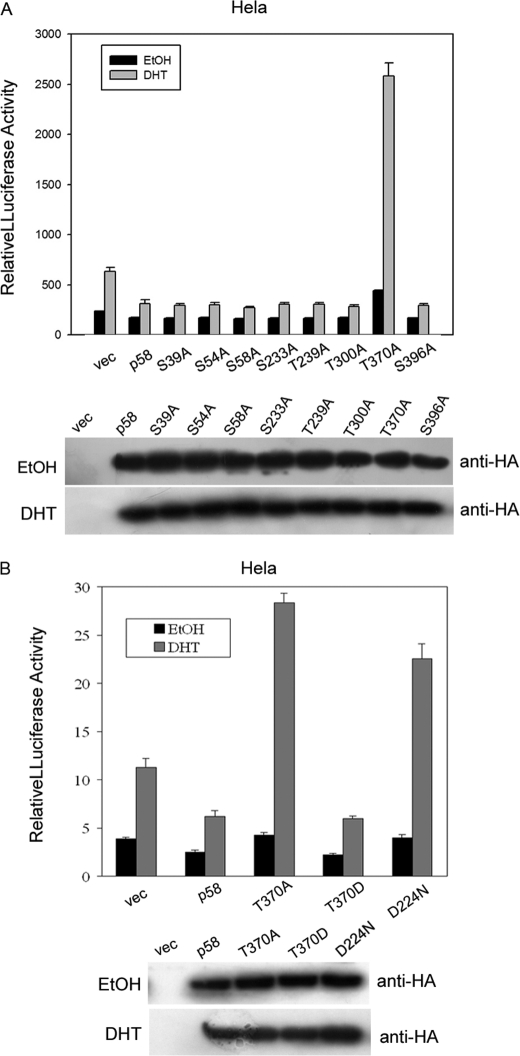

Thr-370 Phosphorylation of CDK11p58 Is Necessary for the Transactivity Repression Ability of AR

We next identified the biological significance of CDK11p58 autophosphorylation. We have previously shown that CDK11p58 represses AR in a kinase activity-dependent manner (15). Therefore, we took advantage of a dual luciferase assay system using the MMTV-LUC and ARE-LUC reporters to investigate whether T370A mutant is still capable of repressing the transcription activity of AR. The luciferase assay showed that CDK11p58 mutant T370D repressed the transactivation of AR as wild type CDK11p58, but T370A significantly enhanced the transactivity of AR as D224N (Fig. 5B). The other Thr/Ser mutants were still capable of inhibiting AR as the wild type CDK11p58 (Fig. 5A). These data suggested that failure of autophosphorylation leads to the loss of CDK11p58 kinase activity and the ability to repress the transactivity of AR.

FIGURE 5.

Thr-370 phosphorylation of CDK11p58 is necessary for the repression of AR transcriptional activation. A, 20 ng of AR and 200 ng of MMTV-LUC were co-transfected with 50 ng of CDK11p58, CDK11p58 mutants, or control vector (vec). The cells were treated with EtOH or 10 nm dihydrotestosterone (DHT) at 24 h after transfection and harvested after another 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. The cell lysates were blotted with HA antibody to show the equal expression levels of CDK11p58 wild type and mutants. B, HeLa cells were transfected with CDK11p58, D224N, T370A, or T370D and treated as described above except that ARE-LUC was used as the reporter plasmid. The lower panel shows the expression levels of several proteins indicated.

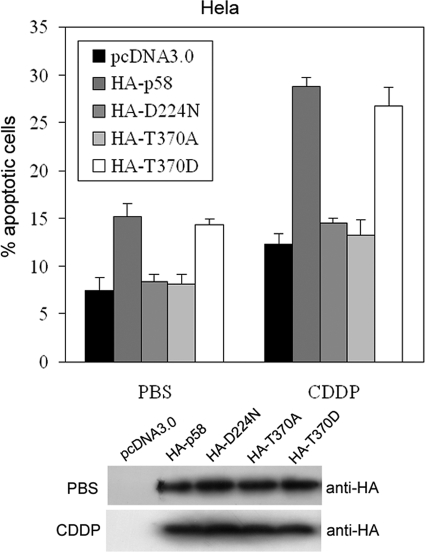

Thr-370 Phosphorylation of CDK11p58 Mediates the Proapoptotic Signaling in HeLa Cells

It has been reported (28) that CDK11p58 potentiates apoptosis of HeLa cells in a kinase-dependent manner. The role of CDK11p58 autophosphorylation in apoptosis was then investigated. The wild type or mutated forms of CDK11p58-transfected HeLa cells were treated with cisplatin for 12 h to induce apoptosis. The percentage of apoptotic cells in the wild type CDK11p58 and T370D overexpression cells was markedly increased compared with that of the control by FACS assay. However, T370A and D224N showed no significant impacts on the apoptosis of HeLa cells (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the inability to autophosphorylate decreases the proapoptotic role of CDK11p58 in cells.

FIGURE 6.

Thr-370 phosphorylation of CDK11p58 mediates the proapoptotic signaling in HeLa cells. HeLa cells transfected with the empty vector, HA-CDK11p58, HA-D224N, HA-T370A, or HA-T370D expression vectors were harvested after PBS or cisplatin (CDDP) treatment (5 μg/ml), fixed in ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide. The apoptotic rates were counted as the sub-G1 event by flow cytometry (n = 3; p < 0.05). The lower panel shows expression levels of CDK11p58 wild type and its mutants.

DISCUSSION

The findings presented here demonstrate for the first time that CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated at Thr-370, and the autophosphorylation of CDK11p58 is essential for its dimerization, kinase activity, and intracellular functions, including the regulation of nuclear receptor transactivation and cancer cell proliferation.

CDK11p58 is involved in a variety of important regulatory pathways in eukaryotic cells, including cell cycle control, apoptosis, neuronal physiology, differentiation, and transcription (22–24). It has been well documented that CDK11p58 is closely related to cell apoptosis and repression of nuclear receptor transactivation in a kinase-dependent manner (3). Although CDK11p58 functions are associated with its kinase activity, little is known about the regulation of its kinase activity.

Protein kinases can be autoactivated by autophosphorylation within their own activation segment (25). We find that CDK11p58 is autophosphorylated as a Ser/Thr kinase, and its kinase activation is dependent on its autophosphorylation according to the in vitro kinase assay. D224N mutants lose the kinase activity, whereas they fail to be autophosphorylated. Moreover, autophosphorylation/autoactivation of protein kinase is usually related to the homodimerization. For example, disruption of JNK2α2 dimerization through specific mutations in the α-region resulted in loss of nuclear localization, loss of autophosphorylation, and decreased tumorigenicity (18). Thus, the autophosphorylation of CDK11p58 may be related to its dimerization. By coimmunoprecipitation in vivo, we found the homointeraction between the wild type CDK11p58 proteins and the heterointeraction between the wild type CDK11p58 and D224N mutant. Interestingly, although D224N was still capable of binding to the wild type CDK11p58, it did not bind to itself. Cross-linking assays also demonstrated that the wild type CDK11p58 could form dimers, but D224N could not be dimerized, and it could not be autophosphorylated in vitro either, which suggested that the loss of kinase activity of D224N may be due to its inability to autophosphorylate and form homodimers. In contrast, the other mutant, K111N, which was still able to show homointeraction or binding to the wild type CDK11p58, exhibited minor kinase activity in vivo and in vitro. To analyze CDK11p58 dimerization in its native state, we used size exclusion gel filtration chromatography. Gel filtration of recombinant wild type CDK11p58 resulted in two distinct peaks at 16 and 27 ml, which represented the dimeric or monomeric form. This finding suggests that CDK11p58 dimers are not stably bound and therefore do not occur through a covalent interaction. If the dimer is a stable chemical form, only a single chromatographic peak should be obtained. CDK11p58 dimerization is the result of a monomer-dimer equilibrium, so two peaks were detected. Interestingly, the kinase activity of dimeric and monomeric CDK11p58 made no difference. The mechanism for this remains to be identified, but because studies with ERK2 have shown that only homodimers are transported to the nucleus (26, 27), we speculated that the dimer and monomer CDK11p58 might have different locations and biofunctions in cells, although both of them were kinase-activated.

By alanine mutagenesis scan, we discovered that Thr-370 is the autophosphorylation site of CDK11p58. T370A, which was not phosphorylated by the wild type CDK11p58, lost its kinase activity and the capability to form dimers through the in vitro kinase assay and cross-linking assay. However, the T370D mutation, which mimicked the phosphorylated CDK11p58, was kinase-activated and dimerized. These results confirm that maybe the CDK11p58 autophosphorylation is required for its dimerization and kinase activity. The T370A mutation could disrupt the secondary or tertiary structure of CDK11p58 so as to lose the ability to form dimers. Taken together, we have enhanced our understanding of the mechanisms of CDK11p58 autophosphorylation, and we have shown that autophosphorylation is important for CDK11p58 dimerization and kinase activity.

However, more specific mechanisms for CDK11p58 dimer formation and the relationship among autophosphorylation, dimerization, and kinase activity require further investigation. We are planning to pin down the exact amino acid responsible for dimerization and to create the site mutant lacking the dimer forming capability to study how dimerization participates in the kinase activity.

It was reported by our group that cyclin D3-CDK11p58 complexes are involved in the negative regulation of AR-mediated transactivation (15). Similar to the kinase-dead mutant D224N (15), T370A was unable to repress the transactivation of AR in the dual luciferase assay. Other mutants, especially T370D represses AR-mediated transcription activity. Additionally, the T370A mutant also failed to enhance the cell apoptosis, but T370D could promote the cell apoptosis. CDK11p58 may act as an oncogene, and Thr-370 mutants may be expressed ubiquitously in cancer cells to induce the initiation and development of the tumors, and this requires further research. Overall, our data indicate that the biological functions of CDK11p58 such as transcription repression and proapoptotic effect, are dependent on the kinase activity that is induced by its autophosphorylation.

In conclusion, our results show that CDK11p58 can form homodimers in cells to provide the structural basis for autophosphorylation at Thr-370, which further induces its kinase activity toward downstream proteins. By this mechanism, CDK11p58 exerts its regulatory effects on various molecular and cellular activities, including transcription and cell proliferation, which may lay the foundation for the initiation and development of some tumors.

This work was supported by National Natural Scientific Foundation of China Grants 30770426, 30930025, and 30900266; Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (B110); National Science Foundation for Fostering Talents in Basic Research of the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant J0730860; State Key Project Specialized for Infectious Diseases Grants 2008ZX10002-015, 2008ZX10002-021, 2008ZX10001-02, and 2008ZX10004-014; and National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) Grants 2010CB912100 and 2010CB912104.

- AR

- androgen receptor

- Ab

- antibody

- CIP

- calf intestinal phosphatase

- DSS

- disuccinimidyl suberate

- MMTV

- murine mammary tumor virus.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bunnell B. A., Heath L. S., Adams D. E., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7467–7471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trembley J. H., Hu D., Hsu L. C., Yeung C. Y., Slaughter C., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2589–2596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lahti J. M., Xiang J., Heath L. S., Campana D., Kidd V. J. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu D., Mayeda A., Trembley J. H., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8623–8629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cornelis S., Bruynooghe Y., Denecker G., Van Huffel S., Tinton S., Beyaert R. (2000) Mol. Cell 5, 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beyaert R., Kidd V. J., Cornelis S., Van de Craen M., Denecker G., Lahti J. M., Gururajan R., Vandenabeele P., Fiers W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11694–11697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ariza M. E., Broome-Powell M., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J., Nelson M. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28505–28513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim J. T., Mansukhani M., Weinstein I. B. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5156–5161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang D., Kidd V. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28549–28552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai M. M., Zhang S. W., Zhang S., Chen S., Yan J., Zhu X. Y., Hu Y., Chen C., Gu J. X. (2002) Mol. Cell Biochem. 238, 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petretti C., Savoian M., Montembault E., Glover D. M., Prigent C., Giet R. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 418–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu D., Valentine M., Kidd V. J., Lahti J. M. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 2424–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yun X., Wu Y., Yao L., Zong H., Hong Y., Jiang J., Yang J., Zhang Z., Gu J. (2007) Mol. Cell Biochem. 304, 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang S., Cai M., Zhang S., Xu S., Chen S., Chen X., Chen C., Gu J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35314–35322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zong H., Chi Y., Wang Y., Yang Y., Zhang L., Chen H., Jiang J., Li Z., Hong Y., Wang H., Yun X., Gu J. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 7125–7142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng C., Kong X., Wang H., Gan H., Hao Y., Zou W., Wu J., Chi Y., Yang J., Hong Y., Chen K., Gu J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8786–8796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chi Y., Hong Y., Zong H., Wang Y., Zou W., Yang J., Kong X., Yun X., Gu J. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nitta R. T., Chu A. H., Wong A. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34935–34945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyake Z., Takekawa M., Ge Q., Saito H. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 2765–2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dey M., Cao C., Dar A. C., Tamura T., Ozato K., Sicheri F., Dever T. E. (2005) Cell 122, 901–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kong X., Gan H., Hao Y., Cheng C., Jiang J., Hong Y., Yang J., Zhu H., Chi Y., Yun X., Gu J. (2009) J Biochem. 146, 417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen C., Yan J., Sun Q., Yao L., Jian Y., Lu J., Gu J. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harper J. W., Adams P. D. (2001) Chem. Rev. 101, 2511–2526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trembley J. H., Loyer P., Hu D., Li T., Grenet J., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J. (2004) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 77, 263–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pike A. C., Rellos P., Niesen F. H., Turnbull A., Oliver A. W., Parker S. A., Turk B. E., Pearl L. H., Knapp S. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 704–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adachi M., Fukuda M., Nishida E. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5347–5358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khokhlatchev A. V., Canagarajah B., Wilsbacher J., Robinson M., Atkinson M., Goldsmith E., Cobb M. H. (1998) Cell 93, 605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li Z., Wang H., Zong H., Sun Q., Kong X., Jiang J., Gu J. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 327, 628–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]