Abstract

CD44 is a cell surface adhesion molecule for hyaluronan and is implicated in tumor invasion and metastasis. Proteolytic cleavage of CD44 plays a critical role in the migration of tumor cells and is regulated by factors present in the tumor microenvironment, such as hyaluronan oligosaccharides and epidermal growth factor. However, molecular mechanisms underlying the proteolytic cleavage on membranes remain poorly understood. In this study, we demonstrated that cholesterol depletion with methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which disintegrates membrane lipid rafts, enhances CD44 shedding mediated by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10) and that cholesterol depletion disorders CD44 localization to the lipid raft. We also evaluated the effect of long term cholesterol reduction using a statin agent and demonstrated that statin enhances CD44 shedding and suppresses tumor cell migration on a hyaluronan-coated substrate. Our results indicate that membrane lipid organization regulates CD44 shedding and propose a possible molecular mechanism by which cholesterol reduction might be effective for preventing and treating the progression of malignant tumors.

Keywords: ADAM ADAMTS, Cell Adhesion, Cell Migration, Cholesterol, Lipid Raft, Metalloprotease

Introduction

CD44 is a cell surface receptor for several extracellular matrix components, including hyaluronan (1), and is implicated in a wide variety of biological processes, including cell migration (2) and tumor metastasis (3). The migratory properties of invasive tumor cells are affected both by the interaction between their adhesion molecules and the surrounding extracellular matrices and by growth factor signaling (4). The proteolytic ectodomain cleavage and release (shedding) of membrane proteins is a critical regulatory step in both physiological and pathological processes (5, 6).

Recently, physiological inducers of CD44 shedding have been identified; hyaluronan small fragments, frequently detected in association with pathological conditions including cancer (7), induce CD44 shedding from tumor cells (8). Intracellular signaling via Rac GTPase, elicited by CD44 engagement, leads to ADAM2 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase)-mediated CD44 shedding and tumor cell migration (9). A prominent abnormality of tumor cells such as gliomas is the overexpression of the EGF receptor (10), and EGF induces the shedding of CD44 (11). Although the molecular mechanisms underlying CD44 shedding induced by spatio-temporally ordered intracellular signaling in the tumor microenvironment have been partly clarified (9, 11), the mechanism that triggers CD44 shedding on the membrane is not yet understood.

Lipid rafts, which are microdomains of the plasma membrane that are rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids (12), are thought to exhibit a liquid-ordered phase floating in the liquid-disordered matrix of the plasma membrane. Recent studies have confirmed the importance of lipid rafts and their associated proteins, including CD44, in cancer progression (13). A number of reports have shown that CD44 is present in lipid rafts (14–18). Recently, several reports have demonstrated that lipid rafts play a crucial role in the shedding of various membrane proteins, such as amyloid precursor protein (APP) (19), IL-6 receptor (20), CD30 (21), L1-CAM (22), collagen type XVII (23), and collagen type XXIII (24). These findings prompted us to look at the influence of cholesterol-rich microdomains of the plasma membrane on the localization and functionality of CD44. To examine these interactions, we altered the cellular cholesterol content by treating cells with either methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) or a statin reagent.

In the present study, we demonstrated that MβCD-induced cholesterol depletion enhances the ADAM10-mediated shedding of CD44. We also examined the effect of cholesterol depletion on the localization of CD44. Furthermore, we evaluated the continued reduction of cholesterol with a statin agent and demonstrated that statin treatment enhances CD44 shedding and suppresses tumor cell migration on a hyaluronan-coated substrate. These data point to a molecular mechanism by which cholesterol reduction might be effective for preventing and treating cancer progression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Anti-CD44 mAb Hermes-3 was purified from a hybridoma obtained from American Tissue Culture Collections (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Anti-CD44 mAb BU75 was purchased from Ancell (Bayport, MN). Antibodies to ADAM10, ADAM17, and ADAM9 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-flotillin-1 mAb and anti-transferrin receptor mAb were purchased from BD Biosciences and Invitrogen, respectively. MβCD, cholesterol (5α-cholesten-3β-ol), 4-cholesten-3-one (3-keto-4-cholestene), filipin, hyaluronan, and simvastatin were purchased from Sigma. Hydroxamate-based metalloproteinase inhibitor TAPI-0 (tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor-0) was obtained from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and TIMP-2 were from R&D Systems. Human recombinant EGF was from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany).

Cell Culture and RNA Interference

The human glioblastoma cell line U-251 MG was maintained in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and cells were incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. siRNA was introduced using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. siRNA sequences used for ADAM10 and ADAM17 knockdown have been described previously (9). siRNA for ADAM9 was as follows: 5′-CUCCUUGGAGAUUAACUAGTT-3′ and 5′-CUAGUUAAUCUCCAAGGAGTT-3′. A scrambled irrelevant siRNA (5′-GCGCGCUUUGUAGGAUUCGTT-3′ and 5′-CGAAUCCUACAAAGCGCGCTT-3′) (Dharmacon Research, Lafayette, CO) was used as a control.

Modulation of Cellular Cholesterol

Cells were grown to near confluency in a 24-well plate. Cells undergoing cholesterol depletion were washed twice with serum-free medium and then incubated with 2.5–10 mm MβCD. For cholesterol replenishment, the cells were further treated for 30 min with 0.3 mm cholesterol-MβCD inclusion complex (25). To substitute membrane cholesterol with a cholesterol analog, the cholesterol-depleted cells were reloaded with the steroid 4-cholesten-3-one by incubating them with 0.3 mm 4-cholesten-3-one-MβCD inclusion complex for 30 min. In another series of experiments, cells were treated with 0.5–2 μg/ml filipin for 1 h. For simvastatin experiments, cells were cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in the presence of 1–4 μm simvastatin. The reagents were diluted in serum-free DMEM medium. Cellular cholesterol content was assayed spectrophotometrically using an Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit (Invitrogen).

Filipin Staining

Cells treated with or without MβCD were rinsed with PBS twice and fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde on ice for 15 min. The cells were then rinsed with PBS twice and treated with 50 μg/ml filipin for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were rinsed again and examined by UV excitation.

Soluble CD44 ELISA

The concentration of soluble CD44 in the culture supernatants was determined using a CD44 ELISA kit (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blot Analysis

To detect soluble CD44 in culture supernatants, the culture supernatants were recovered after cholesterol depletion. Insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g) for 20 min, and the supernatants were precleared and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h by constant rotation with Hermes-3 and protein G-conjugated Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The beads were washed three times with PBS, and the immunoprecipitates were eluted with Laemmli's SDS sample buffer. The cells were lysed in 100 μl of RIPA buffer containing 1% SDS (1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 3 μg/ml pepstatin A). The protein samples were boiled with Laemmli's SDS sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride filter. After blocking with 3% BSA, the blot was probed with Hermes-3 or anti-ADAM10, -ADAM17, or -ADAM9 antibody. β-Actin was detected using an anti-β-actin mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as a control. After incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, the blot was developed with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Detergent Extraction of Cells

Cells were treated with MβCD (5 mm) or filipin (1 μg/ml) and washed twice with TNE buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)). Triton X-100-soluble materials were extracted with TNE buffer containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Insoluble materials were further extracted with TNE buffer containing 1% SDS. Equal amounts from each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting. The lipid raft marker GM1 was detected by dot blot analysis using biotinylated cholera toxin subunit B (Invitrogen) and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen). Flotillin-1 and transferrin receptor were detected by Western blotting using the corresponding mAbs as marker proteins of the lipid raft fraction and the non-lipid raft fraction, respectively.

Atmospheric Scanning Immunoelectron Microscopy

Affinity labeling with gold conjugates was performed by a modification of the previous method, and the images were taken by the newly developed atmospheric scanning electron microscope (ASEM) (26). Cells were cultured on a silicone nitride film 100 nm in thickness (formed by chemical vapor deposition and wet etching) in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. The cells were treated with 5 mm MβCD for 1 h and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. For the detection of CD44 on the cell surface, the cells were incubated with 1% skim milk/PBS for 30 min, Hermes-3 mAb for 1 h, and then Alexa Fluor 488- and Nanogold (1.4 nm)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Nanoprobes, Inc., Yaphank, NY) for 30 min. The Nanogold signal was enhanced using GoldEnhance EM (Nanoprobes) at room temperature for 5 min. The labeled cells in 10 mg/ml ascorbic acid solution were directly observed by ASEM.

Flow Cytometry

The cells were cultured with or without 2 μm simvastatin at 37 °C for 24 h and then detached with PBS containing 0.05% trypsin and incubated with Hermes-3, anti-ADAM10 mAb, or normal mouse IgG. The cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) with CELLQuest research software (BD Biosciences).

Migration Assay

Cell migration was assayed in 24-well Costar Transwell chambers (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) with 6.5-mm-diameter polycarbonate filters of 8-μm pore size. Both sides of the filters were coated with 0.1 mg/ml hyaluronan (from human umbilical cord, Sigma) at 4 °C overnight. The lower compartments of the chambers were filled with 0.6 ml of DMEM containing 0.1% BSA, and the filters were placed into the chamber. The cells were detached by brief exposure to 0.05% trypsin/PBS, resuspended at 2 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM containing 0.1% BSA, added to the upper compartment, and then incubated with or without 2 μm simvastatin for 2 h to allow the cells to adhere to the filter. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (25 μg/ml), human EGF (10 ng/ml), and anti-CD44 blocking mAb BU75 (10 μg/ml) were then added to the upper compartment of the wells. The chambers were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells on the upper surface of the filters were wiped off with cotton swabs, and the cells on the lower surface were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and counted under a light microscope in five defined high power fields (× 200).

Statistical Analysis

All data accumulated under each condition from at least three independent experiments are expressed as means ± S.D. Student's t test or ANOVA followed by post hoc Dunnett's test was employed.

RESULTS

Cholesterol Depletion with MβCD Induces CD44 Shedding from Tumor Cells

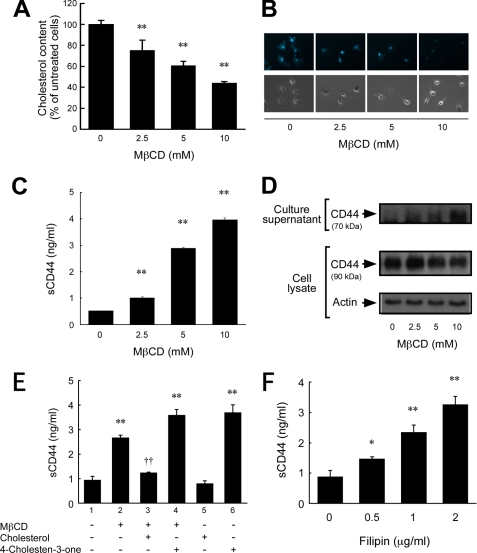

To study the influence of the cellular cholesterol level on CD44 shedding, we treated a human glioblastoma cell line, U-251 MG, which is known to release CD44 upon certain kinds of stimulation (9, 11, 27), with MβCD. MβCD has been shown to extract membrane cholesterol selectively and to disrupt lipid rafts, and it is a practical tool for membrane studies in that it neither binds to nor inserts into the plasma membrane (15, 25). U-251 MG cells treated with 2.5–10 mm MβCD for 1 h showed a concentration-dependent decrease in cellular cholesterol content (Fig. 1A). Incubation with 5 mm MβCD for 1 h reduced the cholesterol level by around 40%. This cholesterol depletion from the plasma membrane was confirmed by staining with filipin. Filipin is a fluorescent polyene antibiotic that binds to cholesterol and is used as a cholesterol probe (20). As shown in Fig. 1B, filipin binding was reduced by MβCD treatment in a dose-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

Cholesterol depletion stimulates CD44 shedding. A, changes in the cellular cholesterol content of U-251 MG glioma cells after treatment with various concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, and 10 mm) of MβCD for 1 h at 37 °C. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). B, staining of cholesterol with filipin. The membrane cholesterol of MβCD-treated cells was detected by filipin staining. Upper panels, fluorescence micrographs of filipin staining by UV excitation. Lower panels, phase contrast micrographs. C, soluble CD44 (sCD44) level in the culture supernatant of MβCD-treated cells. The concentration of soluble CD44 was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). D, immunodetection of CD44 in the culture supernatant and cell lysate of MβCD-treated cells. CD44 in the culture supernatant was immunoprecipitated with an anti-CD44 mAb. The immunoprecipitate and the cell lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. E, effect of replenishment of cholesterol or replacement with a steroid on the shedding of CD44. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 5 mm MβCD for 30 min at 37 °C. To replenish cholesterol, the cells were subsequently incubated with 0.3 mm cholesterol for 30 min at 37 °C. Cellular cholesterol was replaced with a steroid by incubating MβCD-treated cells with 0.3 mm 4-cholesten-3-one for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, the soluble CD44 in the culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (column 1) (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). ††, p < 0.01 when compared with column 2 (Student's t test). F, stimulation of CD44 shedding with filipin. Cells were treated with various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg/ml) of filipin for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2, and the soluble CD44 level in the culture supernatant was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 when compared with untreated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test).

To study the influence of cholesterol depletion on CD44 shedding, the culture supernatants of MβCD-treated U-251 MG cells were collected and subjected to ELISA to determine the concentration of soluble CD44. As shown in Fig. 1C, treatment with MβCD for 1 h resulted in a dose-dependent increase in soluble CD44 released into the medium; the concentration of soluble CD44 was increased as the cellular cholesterol level was reduced. The CD44 shedding in response to MβCD treatment was also evaluated by immunoprecipitating the soluble CD44 in the culture supernatants followed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1D). MβCD treatment resulted in a dose-dependent increase in soluble CD44 of ∼70 kDa, in agreement with the ELISA results. On the other hand, the band intensity of the full-length CD44 in the cell lysate, which was ∼90 kDa, was slightly decreased, indicating that only a small portion of CD44 underwent shedding, and the rest remained uncleaved after MβCD treatment. Similar band patterns are observed when shedding is induced by engagement of CD44 (9). Reduction of cellular CD44 level after MβCD treatment was also observed by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). To ascertain that the cholesterol-dependent shedding is not cell type-specific, we treated other tumor cells with MβCD. The human pancreatic cancer cells PANC-1 shed CD44 by cholesterol depletion, as in the case of stimulation by hyaluronan oligosaccharides (supplemental Fig. S1). Another pancreatic cancer cell line, MIA PaCa-2, which was previously reported to shed CD44 (28), also shed CD44 by MβCD treatment (data not shown). However, a human breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231, which does not exhibit enhanced CD44 shedding under the influence of phorbol myristate acetate, EGF, or hyaluronan oligosaccharides, did not shed CD44 upon cholesterol depletion (supplemental Fig. S1). The results suggest that the CD44 shedding induced by cholesterol depletion is not limited to glioma but extends to other tumor cells as well and that those tumor cells that shed CD44 under physiological stimulation may also be induced to shed CD44 by cholesterol depletion.

To exclude any nonspecific MβCD effect, we replenished the cholesterol using a cholesterol-MβCD inclusion complex as reported previously (25). The cholesterol-MβCD inclusion complex blocked the MβCD-induced shedding of CD44 (Fig. 1E, column 3). To determine whether the effect of cholesterol depletion on CD44 shedding is due to an alteration of membrane fluidity, we used a cholesterol analog, 4-cholesten-3-one (3-keto-4-cholestene); substituting 4-cholesten-3-one for cholesterol in the plasma membrane increases the membrane fluidity (29). As shown in Fig. 1E, substituting steroid 4-cholesten-3-one for cholesterol in the plasma membrane induced CD44 shedding (Fig. 1E, columns 4 and 6), and the effect was more pronounced than that of MβCD. The combination of MβCD and 4-cholesten-3-one treatment gave no further increase in soluble CD44 level than 4-cholesten-3-one treatment alone. These treatments did not affect cell viability. These results together demonstrate that the cholesterol-lowering effect of MβCD was specific and that the effect of cholesterol on the shedding of CD44 is reversible. They also suggest that the effect may be dependent on an alteration of the membrane fluidity.

Filipin Stimulates CD44 Shedding

To ascertain that the cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains regulate CD44 shedding, we used another cholesterol-binding agent, filipin. Filipin binds to cholesterol, a major component of glycolipid microdomains, to form a complex in situ; this prevents the interaction of cholesterol with sphingolipids and thereby decreases the stability of the cholesterol-rich lipid rafts (30, 31). Treating U-251 MG cells with 0.5–2 μg/ml filipin stimulated significant CD44 shedding that increased with dosage (Fig. 1F). These observations indicate that lipid raft disruption may cause the shedding of CD44.

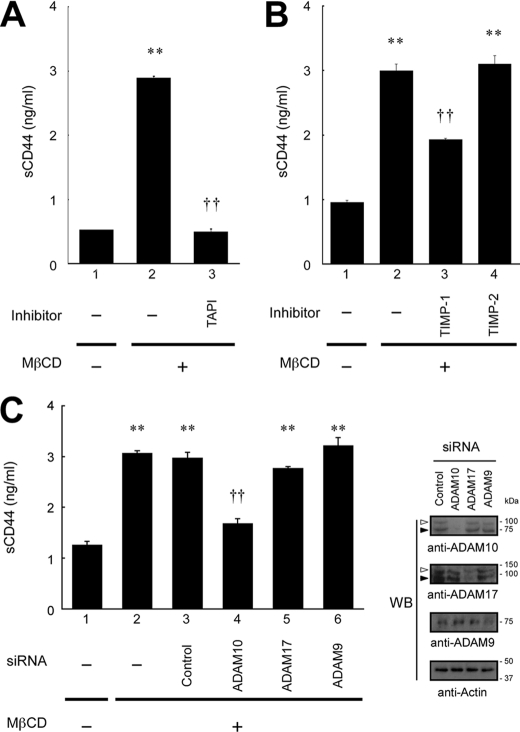

ADAM10 Is Responsible for the CD44 Shedding Induced by Cholesterol Depletion

We next examined the effects of various chemical inhibitors on CD44 shedding. We found that a metalloproteinase inhibitor, TAPI, strongly blocked the MβCD-induced CD44 shedding to the basal level (Fig. 2A). This clearly indicates that the cholesterol depletion with MβCD triggers metalloproteinase-mediated proteolytic cleavage of CD44. Cytochalasin D did not significantly inhibit shedding (supplemental Fig. S2), indicating that cytoskeletal rearrangement is unnecessary for the CD44 shedding induced by low cholesterol.

FIGURE 2.

Influence of various inhibitors and siRNAs on CD44 shedding induced by cholesterol depletion. A, effect of metalloproteinase inhibitor on the shedding of CD44. U-251 MG cells were pretreated for 30 min with TAPI (10 μm) and then treated with MβCD (5 mm) for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in the presence of the inhibitor. After incubation, the level of soluble CD44 (sCD44) in the culture supernatants was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with column 1; ††, p < 0.01 when compared with column 2 (Student's t test). B, effect of TIMPs on the shedding of CD44. Cells were pretreated for 1 h with TIMP-1 or TIMP-2 (10 μg/ml) and then treated with MβCD (5 mm) for 1 h. Soluble CD44 in the culture supernatants was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with column 1; ††, p < 0.01 when compared with column 2 (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). C, effect of siRNA for the knockdown of ADAM proteases on CD44 shedding. Cells were introduced with siRNA specific for ADAM10, ADAM17, or ADAM9 or irrelevant control siRNA and left untreated or treated with 5 mm MβCD for 1 h. The soluble CD44 released into the culture supernatant was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (column 1); ††, p < 0.01 when compared with control siRNA (column 3) (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). Blocking of expression of the ADAMs was monitored by Western blotting (WB, right panels). Open and closed arrowheads indicate the precursor and the mature forms of ADAMs, respectively.

Because lipid rafts are thought to act as a platform for localizing signaling proteins and for eliciting spatially controlled signal transduction (12), we next asked whether intracellular signaling, such as MAPK or PI3K, was involved in the CD44 shedding induced by lowering cholesterol. Neither the MEK inhibitor PD98059 nor the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 significantly inhibited the MβCD-induced shedding (supplemental Fig. S2). Because EGF receptor (EGFR) is localized to lipid rafts (13) and ligand-induced EGFR activation induces CD44 shedding (11), we also tested the effect of a specific EGFR inhibitor, AG1478. AG1478 did not significantly inhibit the CD44 shedding (supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that the mechanism that induces CD44 shedding under MβCD treatment is independent of EGFR activation.

Based on the finding that the CD44 shedding caused by cholesterol depletion is metalloproteinase-mediated, we used TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, the natural inhibitors of metalloproteinases. As shown in Fig. 2B, TIMP-1 exhibited inhibitory effect on MβCD-induced CD44 shedding, whereas TIMP-2 did not. We next performed an RNAi experiment to identify the enzyme responsible. Among the membrane-bound metalloproteinases, ADAM10/Kuzbaninan and ADAM17/TACE (tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme) are the enzymes most frequently identified as the processing enzyme of various transmembrane proteins such as six different EGFR ligands (32, 33). In the case of CD44, recent reports indicate that regulated CD44 cleavage upon the stimulation of CD44 and EGFR is mediated by ADAM10 and that ADAM10 is the constitutive processing enzyme of CD44 (9, 11, 34). Thus, we introduced siRNA specific to ADAM10 and ADAM17, as well as ADAM9, which is a possible regulator of shedding by ADAM10 (35). As shown in Fig. 2C, siRNA to ADAM10 significantly suppressed the MβCD-induced CD44 shedding, whereas siRNA to ADAM17 and ADAM9 did not. The efficient and specific knockdown of each ADAM enzyme was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 2C). These results are consistent with the inhibition pattern by TIMPs in Fig. 2B as in the previous report (9). The difference in the basal level of soluble CD44 between Fig. 2, A–C, may be due to the difference of the procedure of cell treatment. Together, these results strongly suggest that ADAM10 cleaves CD44 on the membrane surface.

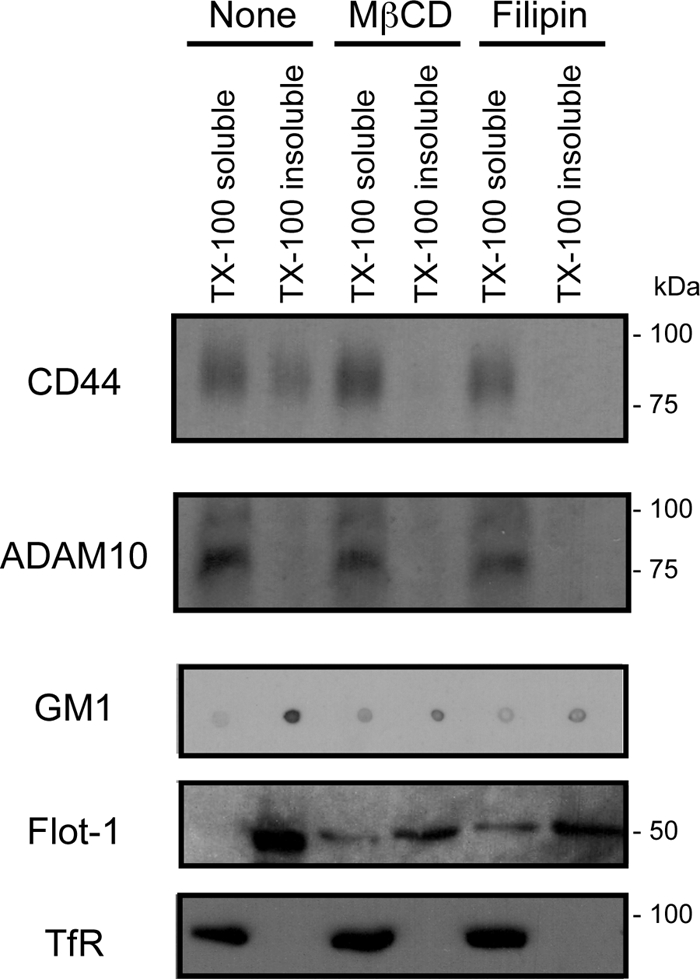

CD44 Distribution in Detergent-soluble and -insoluble Membrane Compartment

It has been suggested that the shedding of several membrane proteins is influenced by their being localized with the processing enzyme (19, 21, 23, 24). ADAM10 has been found to be present in non-lipid raft fractions and excluded from lipid rafts (19, 36), although its substrate CD44 is present in lipid rafts (14–18). Detergent insolubility is a valuable and widely used method for determining whether proteins of interest are localized to the lipid raft. We thus examined whether CD44 and ADAM10 fell into the same domains of detergent solubility after cholesterol depletion. U-251 MG cells were treated with MβCD (5 mm) or filipin (1 μg/ml) or left untreated for 1 h, and the cells were separated into Triton X-100-soluble and -insoluble fractions. Lipid rafts are known to be enriched in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction (12). Although CD44 was detected in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction of untreated cells, CD44 was absent from the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction after MβCD or filipin treatment (Fig. 3). ADAM10 was excluded from the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction. The lipid raft markers, GM1 ganglioside and flotillin-1, were probed with cholera toxin subunit B and anti-flotillin-1 mAb, respectively. The non-lipid raft marker, transferrin receptor, was detected with anti-transferrin receptor mAb. The results indicated that the lipid rafts were distributed to the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction. These results suggest that the CD44 shedding induced by cholesterol depletion may occur within the non-raft region of the membrane.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on the distribution of CD44. U-251 MG cells were treated with MβCD (5 mm) or filipin (1 μg/ml) or left untreated for 1 h, and the cells were separated into Triton X-100 (TX-100)-soluble and -insoluble fractions. The presence of CD44 and ADAM10 in each fraction was determined by Western blotting. GM1 ganglioside was detected as a marker of the lipid raft fraction by dot blot analysis, using biotinylated cholera toxin subunit B and HRP-conjugated streptavidin. Flotillin-1 (Flot-1) and transferrin receptor (TfR) were detected by Western blotting using the corresponding mAbs as marker proteins of the lipid raft fraction and the non-lipid raft fraction, respectively.

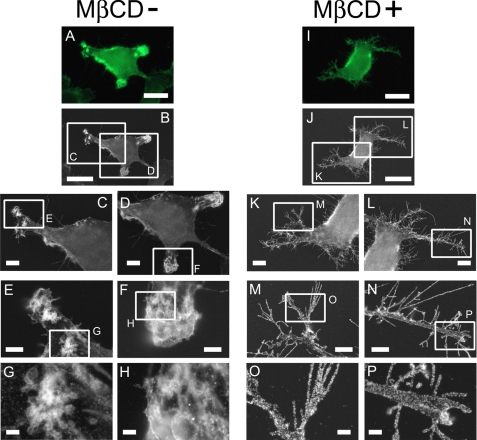

Surface Localization of CD44 by ASEM

The observations described above prompted us to investigate the precise distribution of CD44 on the plasma membrane and how it is changed by raft disruption. To this end, we labeled CD44 on the cell surface of MβCD-treated or untreated cells with Nanogold followed by gold enhancement. Its distribution was observed using the atmospheric scanning electron microscope, ASEM. The ASEM enables direct observation of subcellular structures and the localization of proteins of interest in wet cells at SEM resolution (26). The correlation microscopy using ASEM revealed that CD44 clustering was disordered after cholesterol depletion (Fig. 4). The clustered particles formed white spots 100–1000 nm in size mainly in the “arms” of the untreated cells (Fig. 4, G and H), whereas they were dissociated in the cells treated with 5 mm MβCD (Fig. 4, O and P).

FIGURE 4.

ASEM observation of CD44 distribution on the plasma membrane. Cells were left untreated (A–H) or treated with 5 mm MβCD for 1 h (I–P) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. To detect CD44 on the cell surface, the cells were incubated with anti-CD44 mAb Hermes-3 and then with Alexa Fluor 488- and Nanogold (1.4 nm)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG followed by gold enhancement. The labeled cells were observed using correlation microscope ASEM. After the check using the optical microscope unit (A and I), the cells in ascorbic acid solution were directly observed using ASEM under atmospheric condition, at ×1,500 (B and J), at ×3,000 (C, D, K, and L), at ×10,000 (E, F, M, and N), and at ×30,000 (G, H, O, and P) magnification. Scale bars represent 20 μm (first and second row), 5 μm (third row), 2 μm (fourth row), and 0.5 μm (fifth row).

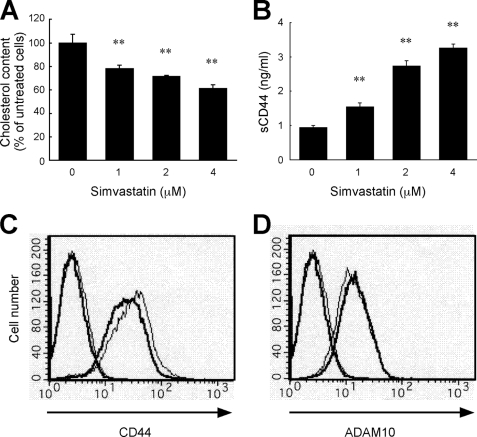

Effect of Statin on CD44 Function

We used simvastatin to examine the effect of chronic depletion of cellular cholesterol content. Simvastatin is one of the statins most frequently used in the clinical treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Statins are widely used inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, the key rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of cholesterol. We examined the effect of chronic suppression of cholesterol synthesis by simvastatin on CD44 function during tumor cell migration. As shown in Fig. 5A, the cellular cholesterol level of U-251 MG glioma cells decreased as the simvastatin dosage increased. CD44 shedding also increased with increased simvastatin dosage in a range that did not affect cell viability (1–4 μm) (Fig. 5B). After treatment with 2 μm simvastatin for 24 h, the cell surface expression of CD44 was decreased, as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 5C), whereas the expression of ADAM10 was slightly increased (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Simvastatin decreases the cellular cholesterol level and enhances CD44 shedding. A, alteration of cellular cholesterol content of U-251 MG glioma cells upon treatment with various concentrations (0, 1, 2, and 4 μm) of simvastatin for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). B, soluble CD44 level in the culture supernatant of simvastatin-treated cells. The cells treated with various concentrations of simvastatin for 24 h were further incubated in fresh serum-free medium for 3 h. The concentration of soluble CD44 was determined by ELISA. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test). C, flow cytometric analysis of the cell surface CD44 of simvastatin-treated cells. Cells were treated with 2 μm simvastatin (thick lines) or left untreated (thin lines) for 24 h at 37 °C and then incubated on ice with anti-CD44 mAb Hermes-3 (right lines) or normal mouse IgG (left lines). The cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. D, flow cytometric analysis of the cell surface ADAM10 of simvastatin-treated cells. Cells were treated as the same method in C, except that anti-ADAM10 mAb was used instead of Hermes-3.

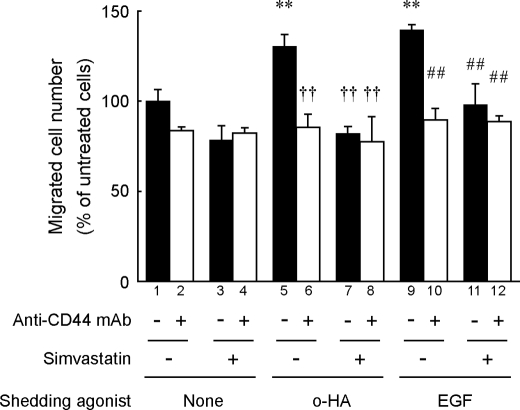

We next examined the effect of simvastatin on glioma cell migration on a hyaluronan-coated substrate because regulated CD44 cleavage enhances cell migration (8, 9, 11, 37). As shown in Fig. 6, simvastatin suppressed the cell migration that had been enhanced by the previously identified CD44 shedding agonists, hyaluronan oligosaccharides or EGF (9, 11). The enhanced migration was also suppressed by treatment with an anti-CD44 blocking mAb, indicating that the enhanced migration was mediated by CD44. The simvastatin treatment of this condition did not affect cell proliferation (supplemental Fig. S3). Taken together, these results suggest that the cholesterol-lowering effect of simvastatin may disturb the regulated CD44 cleavage that is necessary for enhanced cell migration.

FIGURE 6.

Simvastatin suppresses cell migration that is enhanced by microenvironmental factors. The effect of simvastatin on cell migration at hyaluronan-coated substrate was examined by a Boyden chamber-type cell migration assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” U-251 MG cells were incubated with 25 μg/ml hyaluronan oligosaccharides (o-HA) or 10 ng/ml EGF in the presence or absence of 2 μm simvastatin or 10 μg/ml anti-CD44 blocking mAb BU75, at 37 °C for 24 h in hyaluronan-coated Transwell chambers. After incubation, the migrated cells were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and counted microscopically. Data are shown as mean ratio to the control migration. **, p < 0.01 when compared with untreated cells (column 1); ††, p < 0.01 when compared with column 5 among hyaluronan oligosaccharide-treated cells; ##, p < 0.01 when compared with column 9 among EGF-treated cells (ANOVA/Dunnett's test).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study clearly demonstrate that depleting cellular cholesterol with MβCD induces CD44 shedding (Fig. 1, A–D). Replacing the cellular cholesterol with a steroid that increases the membrane fluidity enhanced CD44 shedding (Fig. 1E), showing that the CD44 shedding is affected by the distribution of cholesterol on the membrane. This observation was also supported by another experiment in which CD44 shedding was triggered when the membrane cholesterol was sequestered by filipin (Fig. 1F). Membrane cholesterol serves as a spacer for the hydrocarbon chains of sphingolipids and maintains the assembled microdomains of lipid rafts. Thus, cholesterol depletion leads to the disorganization of lipid raft structure. The effects of various chemical inhibitors and siRNA on the cholesterol depletion-induced CD44 shedding indicate that this enhanced CD44 shedding does not occur through regulated intracellular signaling cascades nor through cytoskeletal rearrangement, but rather through the disorganization of lipid raft structure that affects the ability of ADAM10 to cleave CD44 on the membrane (Fig. 2).

Ectodomain cleavage of transmembrane molecules is controlled not only by activation of the processing enzyme (32) but also by the accessibility of the processing enzyme to the target protein on the membrane. In this context, the membrane environment is crucial in regulating transmembrane molecules. Lipid rafts are cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains that play an important role in the distribution of membrane proteins and their associating signaling partners, which in turn regulate physiological functions (12). Recent studies on the shedding of various membrane proteins show that cholesterol depletion triggers the shedding of these molecules, including APP (19), IL-6 receptor (20), CD30 (21), L1-CAM (22), collagen type XVII (23), and collagen type XXIII (24). It is especially noteworthy that APP and CD30 were found to be strongly associated with lipid rafts, whereas their processing enzymes, ADAM10 and ADAM17, respectively, are excluded from lipid rafts (19, 21). These findings suggest that lipid rafts may play a critical role in regulating the accessibility of processing enzymes to their substrate proteins during both constitutive and regulated shedding (38).

CD44 is reported to be localized to lipid rafts, where it may be sequestered from attack by ADAM10. This is likely to occur through its palmitoylation (39). The results demonstrated in this study indicate that cholesterol depletion prevents the distribution of CD44 to the detergent-insoluble fraction that contains lipid rafts (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the perturbation of the ordered distribution of ADAM10 and CD44 on the membrane increased the probability of enzyme-to-substrate contact that leads to enhanced CD44 shedding. Membrane microdomains such as lipid rafts serve as platforms for the nanoscale assembly of membrane proteins. Until recently, the methods available to visualize these functions on intact cells, especially methods with high spatial resolution, have been limited. The ASEM is a powerful electron microscope that can observe the intact cell surface at 8 nm resolution (26). ASEM observation of CD44 at the cell surface revealed that the CD44 clustering was disordered after cholesterol depletion (Fig. 4).

ADAM10 cleaves various membrane proteins, and most of them are type I transmembrane proteins, such as APP (19), E-cadherin (40), N-cadherin (41), L1-CAM (22), and CD46 (42). It has been shown that ADAM10 is regulated by the lipid composition of the membrane (19, 36). Recently, it was reported that tetraspanin 12, which associates with CD44, regulates APP shedding by ADAM10 (43); it may also regulate CD44 shedding. ADAM10 is an important target of therapeutic strategies to inhibit glioblastoma invasion (44).

The highly enhanced migratory properties are the most prominent features of malignant tumor cells, and they play critical roles in their aggressive invasion and metastatic spread. CD44 has been shown to mediate tumor cell migration (2), and the cleavage of CD44 plays an important role in tumor cell migration (9, 11, 28, 45). This is probably due to the coordinated interaction of CD44 and its processing enzyme, which in turn plays a significant role in the coordinated interplay between cell attachment and detachment to the extracellular matrix during cell migration. The present study showed that chronic cholesterol reduction with an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, simvastatin, enhances CD44 shedding and suppresses CD44-dependent tumor cell migration (Figs. 5 and 6). It is possible that the cholesterol-lowering effect of simvastatin may disturb the regulated CD44 cleavage that is necessary for enhanced cell migration, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the other effects of simvastatin may affect the cell migration. Flow cytometric analysis indicates that simvastatin triggers the shedding of only a small portion of CD44, and the rest remained uncleaved on the cell surface (Fig. 5C). It is possible to speculate that the shed fragment of CD44 suppresses cell motility as an inhibiting molecule for CD44-hyaluronan interaction. However, this is not likely because the cleavage of CD44 seems to work in a pro-migratory manner under certain conditions (9, 11, 28). Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a change in the functionality of cell-bound CD44 may modulate cell migration. Flow cytometric analysis also indicates that the surface expression of ADAM10 is slightly increased by simvastatin treatment (Fig. 5D). The molecular mechanism by which the simvastatin up-regulates the expression of ADAM10 is currently unknown and may be important to the study of therapeutic intervention with statins.

Prevention studies using simvastatin have confirmed its significance in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases (46). It has also been shown that statins may be an effective preventive medicine for dementia, including Alzheimer disease (47). Although the various population-based reports of the effects of statins on cancer are controversial, recent epidemiologic studies suggest that statins inhibit the progression of certain cancers (48). Recent evidence suggests that statins also exhibit anti-tumor effects; simvastatin suppresses the migration of glioma cells (49, 50). Cholesterol reduction is a potential therapy for preventing and suppressing tumor progression, in addition to inhibiting hyaluronidases (51) and ADAMs (44). Our data propose a possible molecular mechanism for prevention and treatment of malignant tumors through the therapeutic use of a statin agent to lower cholesterol.

In conclusion, we have shown that cholesterol depletion enhances CD44 shedding mediated by ADAM10 and that cholesterol depletion affects CD44 localization to the lipid raft. We also evaluated the effect of long term cholesterol reduction using a statin agent and demonstrated that statin enhances CD44 shedding and suppresses CD44-dependent cell migration. Our data provide a new insight into the processing of CD44 on the surface of the cell membrane. This study proposes a possible molecular mechanism by which cholesterol reduction might be effective for preventing and treating the progression of malignant tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Hiroto Kawashima for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- TIMP

- tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- ASEM

- atmospheric scanning electron microscope

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- HMG-CoA

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aruffo A., Stamenkovic I., Melnick M., Underhill C. B., Seed B. (1990) Cell 61, 1303–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas L., Byers H. R., Vink J., Stamenkovic I. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 118, 971–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Günthert U., Hofmann M., Rudy W., Reber S., Zöller M., Haussmann I., Matzku S., Wenzel A., Ponta H., Herrlich P. (1991) Cell 65, 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teodorczyk M., Martin-Villalba A. (2010) J. Cell. Physiol. 222, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huovila A. P., Turner A. J., Pelto-Huikko M., Kärkkäinen I., Ortiz R. M. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alfandari D., McCusker C., Cousin H. (2009) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 153–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lokeshwar V. B., Obek C., Soloway M. S., Block N. L. (1997) Cancer Res. 57, 773–777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sugahara K. N., Murai T., Nishinakamura H., Kawashima H., Saya H., Miyasaka M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32259–32265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murai T., Miyazaki Y., Nishinakamura H., Sugahara K. N., Miyauchi T., Sako Y., Yanagida T., Miyasaka M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4541–4550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Libermann T. A., Nusbaum H. R., Razon N., Kris R., Lax I., Soreq H., Whittle N., Waterfield M. D., Ullrich A., Schlessinger J. (1985) Nature 313, 144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murai T., Miyauchi T., Yanagida T., Sako Y. (2006) Biochem. J. 395, 65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simons K., Ikonen E. (1997) Nature 387, 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patra S. K. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1785, 182–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tarone G., Ferracini R., Galetto G., Comoglio P. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 99, 512–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ilangumaran S., Hoessli D. C. (1998) Biochem. J. 335, 433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oliferenko S., Paiha K., Harder T., Gerke V., Schwärzler C., Schwarz H., Beug H., Günthert U., Huber L. A. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146, 843–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gómez-Móuton C., Abad J. L., Mira E., Lacalle R. A., Gallardo E., Jiménez-Baranda S., Illa I., Bernad A., Mañes S., Martínez-A C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9642–9647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bourguignon L. Y., Singleton P. A., Diedrich F., Stern R., Gilad E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26991–27007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kojro E., Gimpl G., Lammich S., März W., Fahrenholz F. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5815–5820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matthews V., Schuster B., Schütze S., Bussmeyer I., Ludwig A., Hundhausen C., Sadowski T., Saftig P., Hartmann D., Kallen K. J., Rose-John S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38829–38839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Tresckow B., Kallen K. J., von Strandmann E. P., Borchmann P., Lange H., Engert A., Hansen H. P. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 4324–4331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mechtersheimer S., Gutwein P., Agmon-Levin N., Stoeck A., Oleszewski M., Riedle S., Postina R., Fahrenholz F., Fogel M., Lemmon V., Altevogt P. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zimina E. P., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Franzke C. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34019–34024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veit G., Zimina E. P., Franzke C. W., Kutsch S., Siebolds U., Gordon M. K., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Koch M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27424–27435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein U., Gimpl G., Fahrenholz F. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 13784–13793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nishiyama H., Suga M., Ogura T., Maruyama Y., Koizumi M., Mio K., Kitamura S., Sato C. (2010) J. Struct. Biol. 169, 438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okamoto I., Kawano Y., Matsumoto M., Suga M., Kaibuchi K., Ando M., Saya H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25525–25534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kajita M., Itoh Y., Chiba T., Mori H., Okada A., Kinoh H., Seiki M. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 893–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gimpl G., Burger K., Fahrenholz F. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 10959–10974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGookey D. J., Fagerberg K., Anderson R. G. (1983) J. Cell Biol. 96, 1273–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rothberg K. G., Ying Y. S., Kamen B. A., Anderson R. G. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 2931–2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murphy G. (2009) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sahin U., Weskamp G., Kelly K., Zhou H. M., Higashiyama S., Peschon J., Hartmann D., Saftig P., Blobel C. P. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 769–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderegg U., Eichenberg T., Parthaune T., Haiduk C., Saalbach A., Milkova L., Ludwig A., Grosche J., Averbeck M., Gebhardt C., Voelcker V., Sleeman J. P., Simon J. C. (2009) J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 1471–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cissé M. A., Sunyach C., Lefranc-Jullien S., Postina R., Vincent B., Checler F. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40624–40631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harris B., Pereira I., Parkin E. (2009) Brain Res. 1296, 203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sugahara K. N., Hirata T., Hayasaka H., Stern R., Murai T., Miyasaka M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5861–5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wolozin B. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5371–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bourguignon L. Y., Kalomiris E. L., Lokeshwar V. B. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11761–11765 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maretzky T., Reiss K., Ludwig A., Buchholz J., Scholz F., Proksch E., de Strooper B., Hartmann D., Saftig P. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9182–9187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reiss K., Maretzky T., Ludwig A., Tousseyn T., de Strooper B., Hartmann D., Saftig P. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 742–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hakulinen J., Keski-Oja J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21369–21376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xu D., Sharma C., Hemler M. E. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 3674–3681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drappatz J., Norden A. D., Wen P. Y. (2009) Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 519–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suenaga N., Mori H., Itoh Y., Seiki M. (2005) Oncogene 24, 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group (2002) Lancet 360, 7–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jick H., Zornberg G. L., Jick S. S., Seshadri S., Drachman D. A. (2000) Lancet 356, 1627–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Solomon K. R., Freeman M. R. (2008) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gliemroth J., Zulewski H., Arnold H., Terzis A. J. (2003) Neurosurg. Rev. 26, 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu H., Jiang H., Lu D., Xiong Y., Qu C., Zhou D., Mahmood A., Chopp M. (2009) Neurosurgery 65, 1087–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mio K., Carrette O., Maibach H. I., Stern R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32413–32421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.