Abstract

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) regulates amidated lipid transmitters, including the endocannabinoid anandamide and its N-acyl ethanolamine (NAE) congeners and transient receptor potential channel agonists N-acyl taurines (NATs). Using both the FAAH inhibitor PF-3845 and FAAH(−/−) mice, we present a global analysis of changes in NAE and NAT metabolism caused by FAAH disruption in central and peripheral tissues. Elevations in anandamide (and other NAEs) were tissue dependent, with the most dramatic changes occurring in brain, testis, and liver of PF-3845-treated or FAAH(−/−) mice. Polyunsaturated NATs accumulated to very high amounts in the liver, kidney, and plasma of these animals. The NAT profile in brain tissue was markedly different and punctuated by significant increases in long-chain NATs found exclusively in FAAH(−/−), but not in PF-3845-treated animals. Suspecting that this difference might reflect a slow pathway for NAT biosynthesis, we treated mice chronically with PF-3845 for 6 days and observed robust elevations in brain NATs. These studies, taken together, define the anatomical and temporal features of FAAH-mediated NAE and NAT metabolism, which are complemented and probably influenced by kinetically distinguishable biosynthetic pathways that produce these lipids in vivo.

Keywords: anandamide, endocannabinoid, metabolomics, taurine

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) is an integral membrane serine hydrolase that degrades a number of bioactive lipid amides, including the endocannabinoid anandamide (N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine) (1, 2). Anandamide acts as an endogenous ligand for the CB1 and CB2 receptors (3–6), which are two G-protein-coupled receptors that also respond to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of marijuana (7). The genetic or pharmacological inactivation of FAAH results in substantial increases in brain concentrations of anandamide and other N-acyl ethanolamine (NAE) lipids and produces several CB1-dependent neurobehavioral effects in rodents, including anxiolysis (8, 9), anti-depression (10), and anti-nociception (6, 11, 12). Interestingly, these effects are not accompanied by the cognitive and motor dysfunctions associated with direct CB1 agonists such as THC. Taken together, these findings indicate that FAAH is a key regulator of endocannabinoid activity in vivo and suggest further that the enzyme might represent a therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and other nervous system disorders (13, 14).

FAAH-disrupted mice have also shown some phenotypes that are not reversed by the administration of CB1 or CB2 antagonists (12, 15, 16), suggesting that anandamide and/or other FAAH substrates possess bioactivities that extend beyond the endocannabinoid system. To more broadly explore the physiological substrate pool regulated by FAAH, our laboratory has analyzed FAAH(−/−) mice using a metabolomics method based on untargeted LC-MS (17). This approach confirmed known elevations in anandamide and other NAEs in brains and livers of FAAH(−/−) mice and also uncovered a novel class of natural products regulated by FAAH, the N-acyl taurines (NATs). Subsequent in vitro studies showed that FAAH can hydrolyze NATs and that NATs are agonists of the transient receptor potential family of ion channels at concentrations approximately equal to or lower than those found in certain tissues from FAAH(−/−) mice (17, 18).

Despite the aforementioned advances in our understanding of physiological substrates for FAAH, a comprehensive inventory of these lipids across multiple tissues from wild-type versus FAAH-disrupted animals has not yet been performed. Here, we describe a temporal and anatomical atlas of FAAH substrates following acute (i.e., pharmacological) versus chronic (i.e., genetic) blockade of this enzyme in mice. We find that FAAH control over FA amide substrates is tissue specific and, in some cases, influenced by temporal factors that probably reflect differences in the rate of substrate biosynthesis. These discoveries thus lend further support to the hypothesis that multiple pathways exist for the biosynthesis of both NAEs and NATs in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

d4-Anandamide, d8-anandamide, d4-N-palmitoylethanolamine, and pentadecanoic acid (PDA) were purchased from Cayman Chemicals. C15:0-NAT and PF-3845 were synthesized as described previously (17, 19).

Pharmacological inhibition of FAAH

PF-3845 was prepared as a 1 mg/ml saline-emulphor emulsion by vortexing, sonicating, and gently heating neat compound directly into an 18:1:1 v/v/v solution of saline-ethanol-emulphor. FAAH(+/+) mice were administered PF-3845 at a volume of 10 μl/g weight for a final dose of 10 mg/kg. After the indicated amount of time, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and killed by decapitation, and tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Scripps Research Institute.

Preparations of mouse tissue proteomes

Tissues were Dounce-homogenized in PBS, pH 7.5, followed by a low-speed spin (1,400 g, 5 min) to remove debris. The supernatant was then subjected to centrifugation (64,000 g, 45 min) to provide the cytosolic fraction in the supernatant and the membrane fraction as a pellet. The pellet was washed and resuspended in PBS buffer by sonication. Total protein concentration in each fraction was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Fluorophosphonate-rhodamine labeling of tissue proteomes

Tissue proteomes were diluted to 1 mg/ml in PBS, and fluorophosphonate-rhodamine (FP-Rh) was added at a final concentration of 1 µM in a 50 µl total reaction volume. After 30 min at 25°C, the reactions were quenched with 4× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, boiled for 5 min at 90°C, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized in-gel using a flatbed fluorescence scanner (Hitachi).

Anandamide hydrolysis assays

d8-Anandamide (100 µM) was incubated with tissue membranes (50 µg) in PBS (100 µl) at 37°C for 30 min. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 300 µl 2:1 v/v CHCl3-MeOH, doped with 5 nmol PDA, vortexed, then centrifuged (1,400 g, 3 min) to separate the phases. Thirty microliters of the resultant organic phase was injected onto an Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatography-MSD SL instrument. LC separation was achieved with a Gemini reverse-phase C18 column (5 µm, 4.6 mm × 50 mm; Phenomonex) together with a precolumn (C18, 3.5 µm, 2 mm × 20 mm). Mobile phase A was composed of 95:5 v/v H2O-MeOH, and mobile phase B was composed of 65:35:5 v/v/v i-PrOH-MeOH-H2O. Ammonium hydroxide (0.1%) was included to assist in ion formation in negative-ionization mode. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and the gradient consisted of 1.5 min 0% B, a linear increase to 100% B over 5 min, followed by an isocratic gradient of 100% B for 3.5 min before equilibrating for 2 min at 0% B (12 min total per sample). MS analysis was performed with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The capillary voltage was set to 3.0 kV and the fragmentor voltage was set to 70 V. The drying gas temperature was 350°C, the drying gas flow rate was 10 l/min, and the nebulizer pressure was 35 psi. d8-Arachidonic acid was quantified by measuring the area under the peak in comparison to the PDA standard.

Measurement of tissue lipids

Tissues were weighed and subsequently Dounce homogenized in 2:1:1 v/v/v CHCl3-MeOH-Tris, pH 8.0 (8 ml) containing standards for NAEs and NATs (20 pmol d4-N-palmitoylethanolamine, 2 pmol d4-anandamide, and 100 pmol C15:0-NAT). The mixture was vortexed and then centrifuged (1,400 g, 10 min). The organic layer was removed, dried under a stream of N2, resolubilized in 2:1 v/v CHCl3-MeOH (120 µl), and 10 µl of this resolubilized lipid was injected onto an Agilent G6410B QQQ instrument. For measurements of NAEs, LC separation, mobile phase A, and mobile phase B were exactly the same as for the enzyme activity assays, except that 0.1% formic acid was included to assist in ion formation in positive ionization mode. The flow rate for each run started at 0.1 ml/min with 0% B. At 5 min, the solvent was immediately changed to 60% B with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min and increased linearly to 100% B over 10 min. This was followed by an isocratic gradient of 100% B for 5 min at 0.5 ml/min before equilibrating for 3 min at 0% B at 0.5 ml/min (23 min total per sample). The following MS parameters were used to measure the indicated NAEs (precursor ion, product ion): C16:0 (300, 62), C18:0 (328, 62), C18:1 (326, 62), C18:2 (324, 62), C20:4 (348, 62), C22:0 (384, 62), C22:6 (372, 62), d4-16:0 (304, 62), and d4-C20:4 (352, 66). MS analysis was performed with an ESI source. The dwell time for each lipid was set to 60 ms. The capillary was set to 4 kV, the fragmentor was set to 100 V, the delta EMV was set to +300, and the collision energy was set to 11 V for NAE metabolites. The drying gas temperature was 350°C, the drying gas flow rate was 11/min, and the nebulizer pressure was 35 psi. NAEs were quantified by measuring the area under the peak in comparison to the average area of the deuterated standards.

For measurements of NATs, LC separation was the same as for NAEs except that 0.1% ammonium hydroxide was included to assist in ion formation in negative-ionization mode. The following MS parameters were used to measure the indicated NATs (precursor ion, product ion): C16:0 (362.6, 80), C18:0 (390.6, 80), C18:1 (388.6, 80), C18:2 (386.6, 80), C20:4 (410.6, 80), C22:0 (446.7, 80), and C22:6 (434.6, 80). The collision energy was set to 35 V for NAT metabolites. NATs were quantified by measuring the area under the peak in comparison to the area of the C15:0-NAT standard.

RESULTS

FAAH activity in mouse tissues

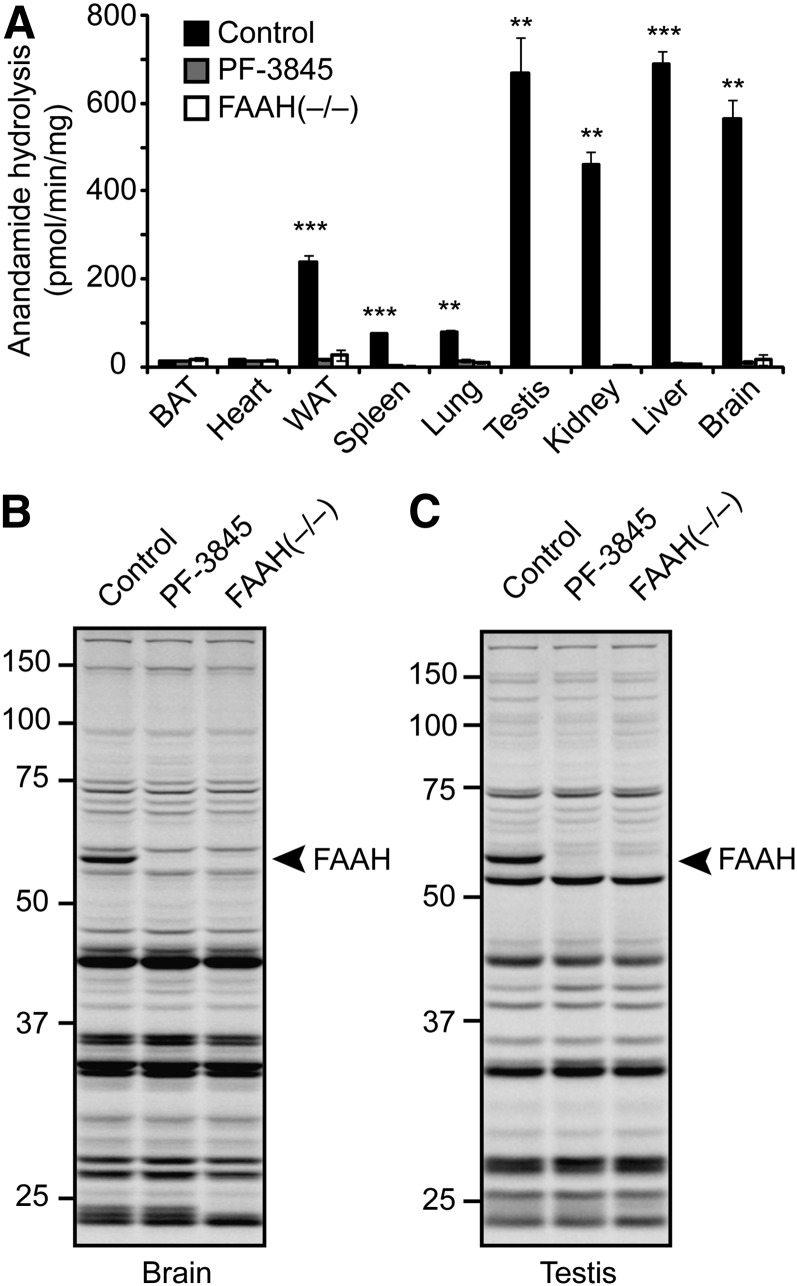

We compared anandamide hydrolysis activity across a panel of tissues from FAAH(+/+) and (−/−) mice, as well as FAAH(+/+) mice treated with vehicle or the selective FAAH inhibitor PF-3845 (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h) (19). Anandamide hydrolysis rates did not differ between naïve and vehicle-treated FAAH(+/+) mice, so, for the sake of clarity, we merged these groups to give one consolidated control group.

Anandamide hydrolysis was highest in brain, testis, liver, kidney, and white adipose tissue (WAT) of FAAH(+/+) mice, with lower concentrations detected in spleen and lung, and negligible activity in brown adipose tissue and heart (Fig. 1A). Virtually all of the observed anandamide hydrolysis activity was ablated in tissues from FAAH(−/−) mice or mice treated with PF-3845, indicating that FAAH is the principal enzyme responsible for anandamide hydrolysis in mammalian tissues, at least under the assay conditions employed. We also analyzed gel-resolvable, active serine hydrolases in these tissues using the serine hydrolase-directed, activity-based probe FP-Rh (20, 21). Consistent with previous studies (22, 23), active FAAH was detected as an ∼60 kDa FP-Rh-labeled protein in brain and testis of control mice, but not PF-3845-treated or FAAH(−/−) mice (Fig. 1B, C). In other tissues, additional serine hydrolases with overlapping masses precluded an assessment of FAAH inactivation using gel-based profiling with FP-Rh (see supplementary Fig. I). These tissue profiles, however, could still be used to confirm the remarkable selectivity that PF-3845 displays for FAAH, because no additional FP-Rh-labeled serine hydrolases other than FAAH were affected by this compound.

Fig. 1.

Pharmacological and genetic disruption of FA amide hydrolase (FAAH) in mice. A: Anandamide hydrolysis activity from tissue membranes prepared from control mice, mice treated with PF-3845 (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h), or FAAH(−/−) mice. B, C: Serine hydrolase activity profiles using the active site-directed probe fluorophosphonate-rhodamine (FP-Rh) from brain (B) or testis (C) membranes prepared from mice as described in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES. FAAH migrates as an ∼60 kDa singlet, indicated by the arrowhead; protein samples were treated with PNGaseF to remove N-linked glycans prior to analysis. For A, ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 for control versus PF-3845 or control versus FAAH(−/−). Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation, n = 3–4/group.

Accumulation and distribution of NAEs in FAAH-disrupted animals

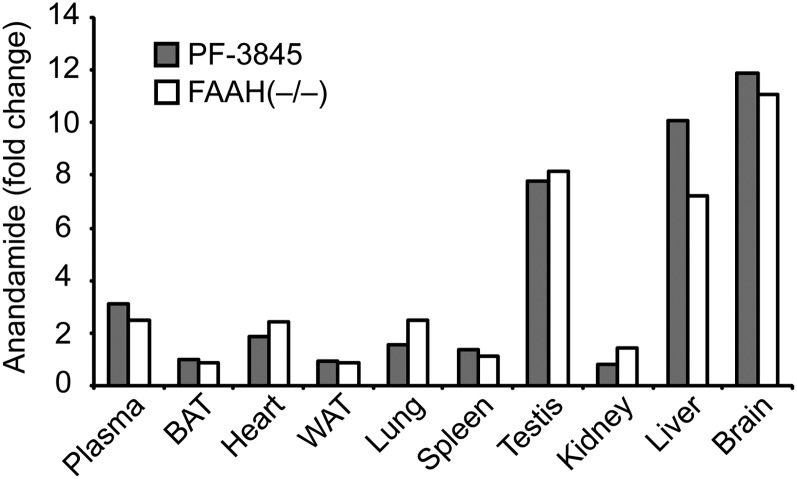

We next examined the effects of genetic or pharmacological blockade of FAAH on NAE accumulation in mouse tissues. Anandamide (C20:4 NAE) was highly elevated (>8-fold) in brain, liver, and testis of FAAH(−/−) or PF-3845-treated mice, and was modestly elevated in some but not all of the other tissues analyzed (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 2). Curiously, the accumulation of anandamide following FAAH disruption was not correlated with the basal concentrations of this lipid or the FAAH enzyme itself. For instance, FAAH disruption caused dramatic elevations in anandamide in testis, but not kidney (Table 1), despite both tissues possessing high basal anandamide concentrations (Table 1) and FAAH activity (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Tissue NAE amounts from control, PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., 3 h), or FAAH(−/−) mice

| Tissue | Group | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C20:4(anandamide) | C22:0 | C22:6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/g | ||||||||

| Plasma | Control | 17 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | ND | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| PF-3845 | 44 ± 3b | 15 ± 5 | 30 ± 2b | 27 ± 5a | 1.2 ± 0.2a | ND | 1.2 ± 0.1b | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 29 ± 2b | 11 ± 1 | 24 ± 3a | 16 ± 3a | 1.0 ± 0.1a | ND | 1.0 ± 0.1 | |

| BAT | Control | 728 ± 96 | 548 ± 71 | 681 ± 65 | 465 ± 43 | 47 ± 6 | 27 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 |

| PF-3845 | 925 ± 197 | 588 ± 129 | 832 ± 143 | 598 ± 73 | 47 ± 3 | 32 ± 11 | 18 ± 2 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 896 ± 48 | 669 ± 128 | 860 ± 131 | 546 ± 45 | 40 ± 7 | 19 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 | |

| Heart | Control | 158 ± 16 | 195 ± 26 | 126 ± 18 | 40 ± 6 | 3 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 5 ± 1 |

| PF-3845 | 233 ± 26 | 230 ± 40 | 177 ± 28 | 87 ± 10a | 5 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 6 ± 1 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 268 ± 60 | 297 ± 71 | 223 ± 58 | 101 ± 12a | 7 ± 1a | 2.5 ± 0.3a | 9 ± 1c | |

| WAT | Control | 467 ± 100 | 282 ± 45 | 380 ± 47 | 122 ± 25 | 5 ± 1 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 6 ± 1 |

| PF-3845 | 462 ± 112 | 181 ± 21 | 400 ± 108 | 165 ± 51 | 4 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 6 ± 2 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 364 ± 50 | 258 ± 43 | 346 ± 43 | 157 ± 14 | 4 ± 1 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 9 ± 1 | |

| Spleen | Control | 332 ± 28 | 363 ± 32 | 138 ± 31 | 30 ± 4 | 5 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 4 ± 1 |

| PF-3845 | 434 ± 30a | 324 ± 22 | 212 ± 9 | 100 ± 4c | 7 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 7 ± 1 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 320 ± 39 | 385 ± 68 | 180 ± 18 | 109 ± 14b | 5 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 5 ± 1 | |

| Lung | Control | 322 ± 37 | 351 ± 34 | 103 ± 16 | 24 ± 5 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| PF-3845 | 449 ± 62 | 448 ± 60 | 179 ± 23 | 72 ± 15a | 5 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 481 ± 36a | 600 ± 8c | 210 ± 30a | 53 ± 1c | 8 ± 1b | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 1b | |

| Testis | Control | 402 ± 47 | 266 ± 40 | 143 ± 27 | 22 ± 5 | 23 ± 2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 3 |

| PF-3845 | 835 ± 67c | 787 ± 74c | 400 ± 25c | 87 ± 11c | 178 ± 9c | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 120 ± 3c | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 897 ± 136a | 630 ± 99a | 367 ± 61a | 40 ± 6a | 186 ± 28c | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 126 ± 22b | |

| Kidney | Control | 359 ± 60 | 312 ± 39 | 225 ± 43 | 107 ± 24 | 36 ± 10 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 16 ± 2 |

| PF-3845 | 590 ± 103a | 507 ± 79a | 410 ± 88a | 202 ± 21b | 30 ± 7 | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 15 ± 2 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 543 ± 58a | 471 ± 48a | 478 ± 42c | 325 ± 34c | 52 ± 10 | 2.4 ± .1c | 22 ± 3 | |

| Liver | Control | 166 ± 20 | 117 ± 21 | 49 ± 10 | 8 ± 1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | ND | 3 ± 1 |

| PF-3845 | 546 ± 86a | 199 ± 40 | 222 ± 31a | 189 ± 3c | 5.9 ± 0.6b | ND | 6 ± 2 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 386 ± 65a | 173 ± 32 | 133 ± 33a | 113 ± 10c | 4.2 ± 0.6b | ND | 4 ± 1 | |

BAT, brown adipose tissue; FAAH, FA amide hydrolase; NAE, N-acyl ethanolamine; WAT, white adipose tissue. All values have units of pmol/g tissue. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4–6/group. ND, not detected.

P < 0.05 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.01 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.001 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

TABLE 2.

Brain NAE amounts from control, acutely PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., 3 h), chronically PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., once per day, 6 days), or FAAH(−/−) mice

| Group | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C20:4(anandamide) | C22:0 | C22:6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/g | |||||||

| Control | 245 ± 49 | 167 ± 41 | 131 ± 25 | 8 ± 2 | 4 ± 1 | 35 ± 6 | 6 ± 1 |

| Acute PF-3845 | 3,502 ± 1,097a | 1,313 ± 491a | 2,435 ± 757a | 169 ± 51b | 44 ± 11b | 36 ± 13 | 31 ± 9a |

| Chronic PF-3845 | 2,562 ± 196b | 1,248 ± 200a | 2,317 ± 100b | 171 ± 28a | 45 ± 4b | 97 ± 27a | 40 ± 3b |

| FAAH(−/−) | 2,836 ± 430b | 1,834 ± 295a | 2,683 ± 422b | 178 ± 43b | 41 ± 8b | 186 ± 40b | 34 ± 6b |

All values have units of pmol/g tissue. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4–6/group.

P < 0.05 for acute PF-3845, chronic PF-3845, or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.01 for acute PF-3845, chronic PF-3845, or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

Fig. 2.

Average fold change in anandamide in various tissues between PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h) or FAAH(−/−) mice versus control mice. The values used for this graph were obtained from Table 1 and Table 2.

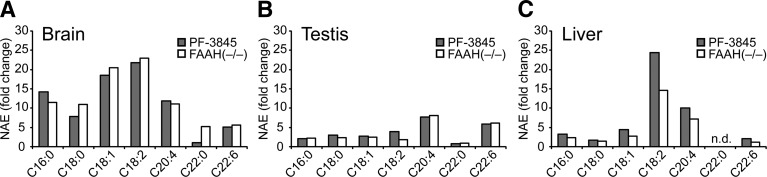

We also measured additional NAEs, including the polyunsaturated species C18:2 and C22:6 NAE, which share physicochemical properties with anandamide, and several saturated or monounsaturated NAEs (C16:0, C18:0, C18:1, and C22:0) (Table 1). Brain was the only organ that showed large increases (>5-fold) in all NAE species following FAAH blockade, although the C22:0 NAE was selectively elevated in FAAH(−/−) mice but not mice treated with PF-3845 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, testis tissue from FAAH-disrupted animals accumulated high amounts of anandamide and C22:6 NAE, but displayed only modest changes in other NAEs (Fig. 3B). Livers from these animals selectively accumulated anandamide and C18:2 NAE, but not C22:6 NAE, and, like testis, showed more-limited accumulation of saturated and monounsaturated NAEs (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Tissue-specific differences in NAE accumulation. A–C: Average fold-change in various NAEs between PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h) or FAAH(−/−) mice versus control mice in brain (A), testis (B), and liver (C). The values used for this graph were obtained from Table 1 and Table 2. n.d., not detected.

Some organs with substantial FAAH activity, such as WAT, did not exhibit changes in NAEs following FAAH blockade (Table 1). Conversely, other tissues that lack FAAH activity, such as heart, showed significant (albeit modest) elevations in several NAEs in FAAH(−/−) or PF-3845-treated mice. Such changes could be explained by transport of NAEs from distal sites of production to organs where FAAH is not expressed. Consistent with this model, most NAEs were significantly elevated in plasma from FAAH(−/−) or PF-3845-treated mice (Table 1). More generally, these findings indicate that the amounts of FAAH activity displayed by tissues are not predictive of the changes in NAEs observed in these organs following FAAH disruption.

Accumulation and distribution of NATs in FAAH-disrupted animals

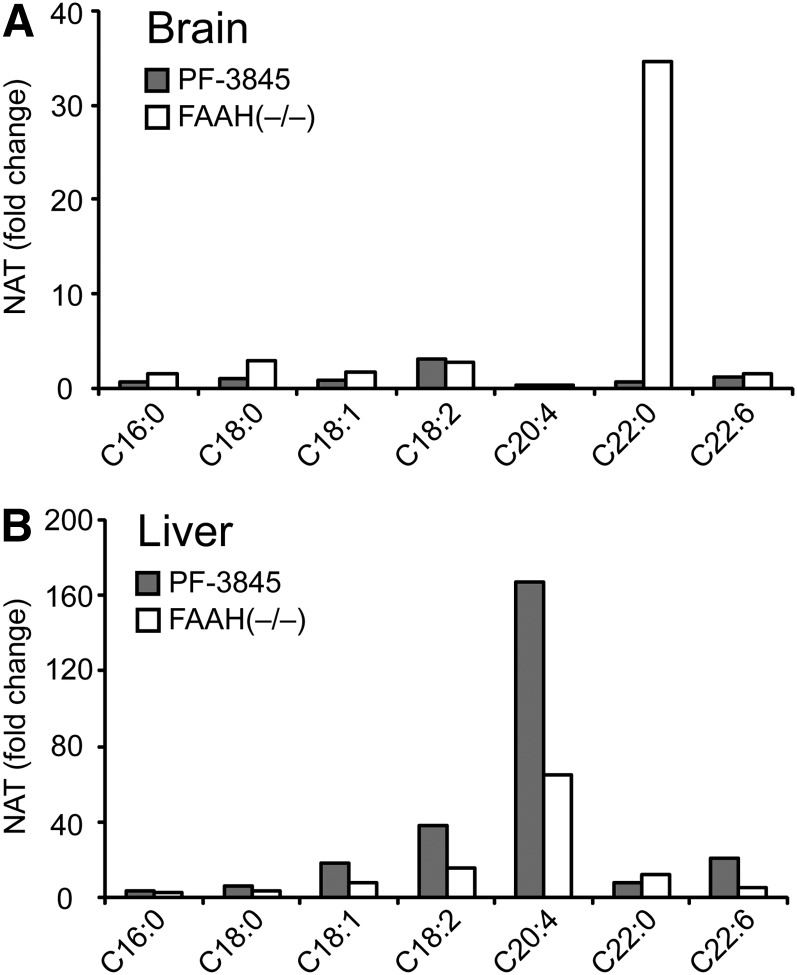

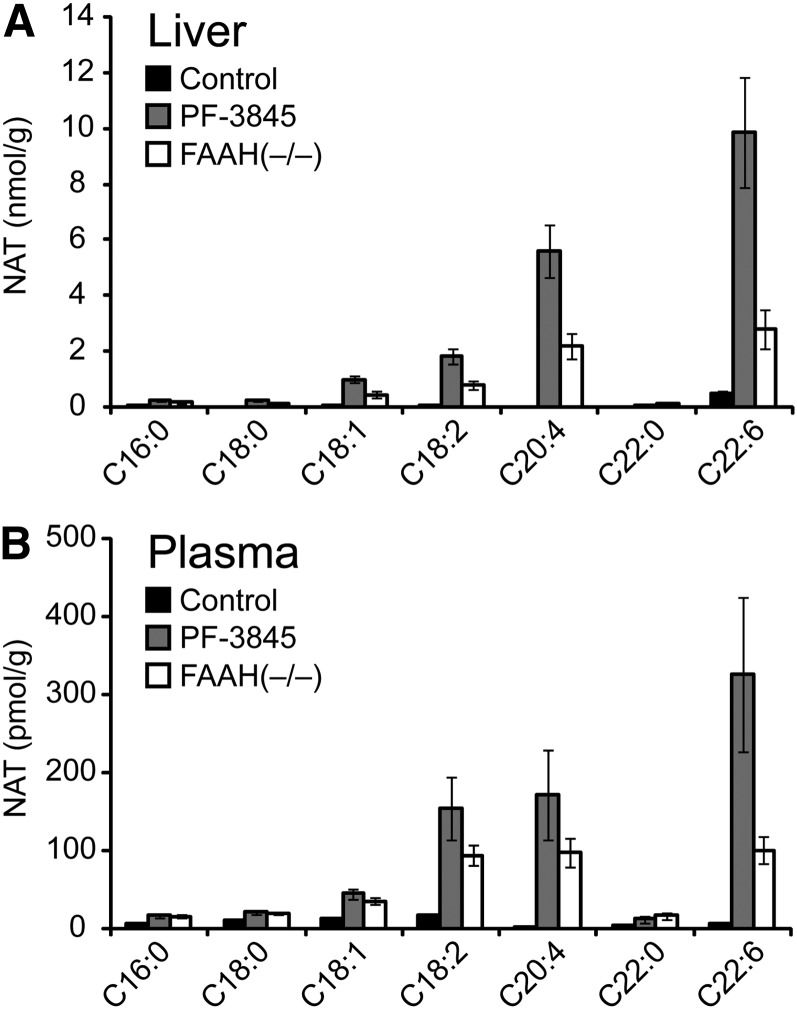

As has been observed in previous studies (17, 18), long-chain saturated NATs, such as C22:0, were highly elevated in brains of FAAH(−/−) mice, whereas liver and kidney tissues from these animals showed large increases (5–100-fold) in polyunsaturated (C20:4, C22:6) NATs (Tables 3, 4, and Fig. 4). Other saturated and monounsaturated NATs were also elevated in liver, but to a more modest degree. In contrast, polyunsaturated NATs were unaltered, or, in the case of C20:4, paradoxically lower in brains from FAAH(−/−) mice (Table 4). Acute inhibitor treatment produced greater elevations in polyunsaturated NATs in liver than were observed in FAAH(−/−) animals, suggesting that chronic FAAH blockade may feed back to inhibit NAT biosynthesis in this organ.

TABLE 3.

Tissue NAT amounts from control, PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., 3 h), or FAAH(−/−) mice

| Tissue | Group | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C20:4 | C22:0 | C22:6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/g | ||||||||

| Plasma | Control | 6 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 18 ± 2 | 4 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 |

| PF-3845 | 17 ± 2b | 22 ± 2a | 45 ± 6a | 155 ± 41a | 172 ± 57a | 13 ± 4 | 327 ± 99a | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 16 ± 3a | 20 ± 2a | 36 ± 4a | 94 ± 14a | 99 ± 18a | 18 ± 4a | 101 ± 17a | |

| BAT | Control | 378 ± 120 | 116 ± 28 | 332 ± 69 | 215 ± 63 | 36 ± 10 | 85 ± 34 | 59 ± 8 |

| PF-3845 | 374 ± 26 | 110 ± 26 | 487 ± 29 | 253 ± 27 | 156 ± 23b | 70 ± 13 | 41 ± 11 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 268 ± 71 | 133 ± 43 | 322 ± 44 | 176 ± 18 | 41 ± 3 | 110 ± 19 | 66 ± 14 | |

| Heart | Control | 222 ± 31 | 723 ± 195 | 353 ± 67 | 238 ± 48 | 34 ± 7 | 44 ± 11 | 29 ± 4 |

| PF-3845 | 229 ± 17 | 667 ± 69 | 268 ± 47 | 327 ± 30 | 70 ± 10a | 35 ± 6 | 47 ± 17 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 160 ± 40 | 783 ± 128 | 269 ± 71 | 190 ± 29 | 23 ± 7 | 45 ± 5 | 21 ± 2 | |

| WAT | Control | 174 ± 18 | 90 ± 17 | 207 ± 31 | 63 ± 7 | 20 ± 10 | 2 ± 1 | 17 ± 5 |

| PF-3845 | 189 ± 34 | 79 ± 16 | 223 ± 34 | 64 ± 7 | 21 ± 7 | 4 ± 2 | 18 ± 4 | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 179 ± 18 | 109 ± 23 | 216 ± 57 | 52 ± 12 | 20 ± 7 | 4 ± 2 | 16 ± 4 | |

| Spleen | Control | 96 ± 21 | 162 ± 26 | 92 ± 29 | 73 ± 11 | 39 ± 6 | 41 ± 3 | 62 ± 7 |

| PF-3845 | 85 ± 4 | 213 ± 12 | 106 ± 11 | 121 ± 17 | 122 ± 29a | 55 ± 6 | 428 ± 90a | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 57 ± 2 | 149 ± 5 | 61 ± 3 | 78 ± 7 | 92 ± 19a | 92 ± 10a | 255 ± 73a | |

| Lung | Control | 69 ± 13 | 152 ± 31 | 136 ± 36 | 58 ± 6 | 18 ± 3 | 131 ± 51 | 14 ± 4 |

| PF-3845 | 189 ± 91 | 82 ± 33 | 106 ± 43 | 123 ± 47 | 81 ± 12a | 101 ± 68 | 114 ± 13a | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 251 ± 20b | 569 ± 12c | 425 ± 33c | 263 ± 29b | 163 ± 4c | 164 ± 16 | 101 ± 6c | |

| Testis | Control | 25 ± 3 | 43 ± 7 | 21 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 | 32 ± 4 | 6 ± 1 | 36 ± 3 |

| PF-3845 | 32 ± 2 | 65 ± 13 | 24 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 48 ± 7 | 5 ± 1 | 57 ± 6a | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 23 ± 6 | 61 ± 21 | 17 ± 4 | 17 ± 9 | 66 ± 14 | 21 ± 2b | 80 ± 14a | |

| Kidney | Control | 113 ± 13 | 132 ± 16 | 142 ± 24 | 118 ± 17 | 197 ± 37 | 31 ± 7 | 178 ± 29 |

| PF-3845 | 287 ± 23c | 405 ± 61b | 663 ± 95c | 782 ± 53c | 1120 ± 176b | 35 ± 11 | 737 ± 87c | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 316 ± 54b | 773 ± 87c | 723 ± 82c | 682 ± 55c | 957 ± 108c | 155 ± 16c | 737 ± 115b | |

| Liver | Control | 64 ± 7 | 40 ± 6 | 54 ± 8 | 48 ± 5 | 34 ± 4 | 9 ± 1 | 474 ± 136 |

| PF-3845 | 254 ± 29b | 245 ± 23b | 995 ± 119b | 1,855 ± 270b | 5,629 ± 954b | 77 ± 9b | 9,876 ± 1,963a | |

| FAAH(−/−) | 181 ± 10c | 144 ± 6c | 468 ± 98a | 776 ± 151a | 2,204 ± 464a | 119 ± 7c | 2,826 ± 701a | |

NAT, N-acyl taurine. All values have units of pmol/g tissue. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4–6/group.

P < 0.05 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.01 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.001 for PF-3845 or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

TABLE 4.

Brain NAT amounts from control, acutely PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., 3 h), chronically PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg i.p., once per day, 6 days), or FAAH(−/−) mice

| Group | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C20:4 | C22:0 | C22:6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/g | |||||||

| Control | 184 ± 20 | 148 ± 25 | 124 ± 17 | 5 ± 2 | 83 ± 23 | 20 ± 6 | 38 ± 3 |

| Acute PF-3845 | 142 ± 20 | 143 ± 26 | 99 ± 16 | 16 ± 2a | 31 ± 3b | 15 ± 3 | 50 ± 6 |

| Chronic PF-3845 | 155 ± 65 | 600 ± 11b | 362 ± 38a | 30 ± 3b | 48 ± 1a | 529 ± 113a | 88 ± 10a |

| FAAH(−/−) | 283 ± 23 | 438 ± 30b | 207 ± 13a | 14 ± 2a | 35 ± 1b | 680 ± 62b | 59 ± 7 |

All values have units of pmol/g tissue. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4–6/group.

P < 0.05 for acute PF-3845, chronic PF-3845, or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

P < 0.01 for acute PF-3845, chronic PF-3845, or FAAH(−/−) versus control.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of N-acyl taurine (NAT) accumulation in liver and brain tissue from PF-3845-treated and FAAH(−/−) mice. A, B: Average fold change in various NAT concentrations for PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h) or FAAH(−/−) mice versus control mice in brain (A) and liver (B). The values used for this graph were obtained from Table 1.

Whereas the predominant NATs in liver and brain of FAAH(−/−) mice were polyunsaturated (∼5–10 nmol/g) and long-chain, saturated (∼700 pmol/g), respectively, shorter chain NATs were the major species that accumulated in lung, with C18:0 and C18:1 NATs showing the highest absolute concentrations (∼500 pmol/g) (Table 3). In the remaining peripheral organs, the NATs as a group were largely unchanged except for one or two individual species in each organ. For example, testis and spleen each showed ∼4-fold and ∼5-fold elevations in C22:0 NAT and C22:6 NAT, respectively, but not the other NATs. NATs, like NAEs, were unchanged in WAT.

It is noteworthy that liver and plasma NAT profiles were quite similar (Fig. 5A, B). This finding could point to the existence of a NAT transport system that transfers NATs from liver to the circulation, where these lipids could then be delivered to other tissues. We speculate that this might occur in spleen, for instance, which displayed a NAT profile similar that seen in liver, with principal elevations in polyunsaturated NATs.

Fig. 5.

NAT amounts in liver and plasma of PF-3845-treated and FAAH(−/−) mice. A, B: Absolute concentrations of various NATs in liver (A) and plasma (B) from control, PF-3845-treated (10 mg/kg, i.p., 3 h), and FAAH(−/−) mice. The values used for this graph were obtained from Table 1. Data are presented as the means ± SEM, n = 4–6/group.

Differences in FA amide amounts following acute versus chronic FAAH disruption

A curious disconnect was observed for NAT profiles in brain, where long-chain saturated NATs were highly elevated in FAAH(−/−) mice but not in acutely FAAH-inhibited animals (Fig. 4A). This phenomenon has been reported previously and attributed to a potentially slow biosynthetic pathway for NATs in the nervous system (18). We set out to test this hypothesis by treating mice with PF-3845 chronically for 6 days (10 mg/kg, i.p., once-per-day dosing) and then measuring brain lipids. This treatment regime produced substantial increases in saturated NATs (e.g., C18:0, C22:0) that approximated the amounts observed in FAAH(−/−) mice (Table 4). Interestingly, a similar, albeit less-pervasive trend was observed for NAEs, where C22:0 NAE also accumulated to significantly higher amounts in chronic versus acute PF-3845-treated mice (Table 2). These data contrast with the kinetic profiles for shorter chain and mono/poly-unsaturated NAEs, which accumulated quickly in brain and peripheral tissues following FAAH disruption and then plateaued at new steady-state concentrations that are apparently sustained throughout life [based on comparisons with FAAH(−/−) mice]. The markedly different kinetic profiles observed for long-chain saturated versus shorter chain/unsaturated NAEs/NATs indicate that these subsets of FA amides are probably produced by distinct biosynthetic pathways.

DISCUSSION

Several previous studies have reported changes in NAE and NAT lipids in rodents with pharmacological or genetic disruptions of FAAH (6, 12, 17, 18, 24, 25). Most of these reports focus on a single or select number of tissues, and few, if any, have compared acute versus chronic disruption of FAAH in a quantitative manner. Here, we set out to establish an anatomical inventory of NAE and NAT metabolism across a broad range of central and peripheral tissues from FAAH inhibitor-treated and FAAH(−/−) mice. This analysis revealed that despite the presence of FAAH in most tissues, there were marked tissue-specific differences in the accumulation of both NAEs and NATs in FAAH-disrupted animals. Most tissues that express FAAH showed some elevations in a subset of the NAEs or NATs, but each had a distinct lipid profile.

These differences may reflect the presence of distinct sets of biosynthetic enzymes for NAEs and NATs, which may shape the rate of accumulation and acyl chain distribution of FAAH substrates. The production of long-chain saturated and monounsaturated NAEs in the brain has already been characterized to occur by the action of N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD), an enzyme that liberates NAEs from an unusual class of N-acylated phospholipids (26, 27). However, the pathways that produce other subsets of NAEs and NATs remain poorly characterized. Our data point to anatomical locations where these different biosynthetic pathways are probably operational. For instance, both brain and testis appear to possess an enzymatic route to rapidly generate polyunsaturated NAEs, including anandamide. That testis can furthermore accumulate anandamide without substantial elevations in shorter chain NAEs suggests that at least two additional NAPE-PLD-independent NAE biosynthetic pathways may exist, one for polyunsaturated NAEs and the other for shorter chain saturated and mono-unsaturated NAEs.

Similar complexity was found for NATs, where liver appears to contain a highly active biosynthetic pathway for polyunsaturated NATs, whereas brain has a much slower process for producing long-chain saturated NATs. In vitro evidence suggests that NATs may originate from the enzymatic conjugation of taurine with fatty acyl-CoAs, analogous to the formation of bile salts (18, 28). If this is the endogenous pathway for NAT production in liver, it would be interesting to examine whether the acyl-CoA fraction of the liver metabolome shows selective decreases in arachidonoyl- and docosahexaenoyl-CoA in FAAH-disrupted animals. These lipids have been typically reported in the range of less than 10 nmol/g in liver (29, 30), and in our data, the C20:4/C22:6 NATs increase by a comparable stoichiometry. We hypothesize that different enzymes catalyze the acyltransferase reaction in liver and brain to account for their markedly distinct NAT profiles following FAAH inactivation. Finally, the accumulation of NATs in brain tissue of FAAH-disrupted animals over the course of days rather than hours is a cogent reminder that slow metabolic pathways exist in mammals and may only reveal themselves following prolonged perturbations of up- or downstream enzymes.

We were particularly intrigued by the similarity of NAT profiles in liver and plasma from FAAH-disrupted animals, which showed nearly identical acyl chain distributions (differing only in the absolute concentration of each NAT). Such an observation is reminiscent of endocrines secreted by the liver, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (31) or thrombopoietin (32, 33) and suggests that NATs may also function as endocrine-like signaling molecules. How NATs are released from liver and taken up into other tissues remains unknown, but they could be substrates for organic anion transporters, which are responsible for bile salt uptake (34).

In summary, our near-comprehensive anatomical portrait of physiological substrates for FAAH underscores key features of FA amide metabolism in mammals, emphasizing, in particular, that FAAH control over specific NAEs and NATs is strongly influenced by the host tissue. Such differences in FAAH substrate accumulation provide evidence for the existence of multiple biosynthetic pathways for NAEs and NATs in vivo, some of which are highly active (polyunsaturated NAE and NAT production in brain/testis and liver, respectively), whereas others are much slower (long-chain saturated NAE and NAT production in brain). The molecular characterization of these pathways promises to deliver new enzymatic targets whose perturbation should enrich our understanding of the physiological functions of individual branches of the FA amide family.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- FAAH

- fatty acid amide hydrolase

- FP-Rh

- fluorophosphonate-rhodamine

- NAE

- N-acyl ethanolamine

- NAPE-PLD

- N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D

- NAT

- N-acyl taurine

- PDA

- pentadecanoic acid

- THC

- Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA-017259 and DA-009789 and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other granting agencies.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one figure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cravatt B. F., Giang D. K., Mayfield S. P., Boger D. L., Lerner R. A., Gilula N. B. 1996. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 384: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon G. M., Cravatt B. F. 2010. Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: serine hydrolases as a case study. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 11051–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn K., McKinney M. K., Cravatt B. F. 2008. Enzymatic pathways that regulate endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system. Chem. Rev. 108: 1687–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naidu P. S., Kinsey S. G., Guo T. L., Cravatt B. F., Lichtman A. H. 2010. Regulation of inflammatory pain by inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 334: 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinsey S. G., Long J. Z., O'Neal S. T., Abdullah R. A., Poklis J. L., Boger D. L., Cravatt B. F., Lichtman A. H. 2009. Blockade of endocannabinoid-degrading enzymes attenuates neuropathic pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330: 902–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cravatt B. F., Demarest K., Patricelli M. P., Bracey M. H., Giang D. K., Martin B. R., Lichtman A. H. 2001. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 9371–9376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda L. A., Lolait S. J., Brownstein M. J., Young A. C., Bonner T. I. 1990. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 346: 561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathuria S., Gaetani S., Fegley D., Valino F., Duranti A., Tontini A., Mor M., Tarzia G., La Rana G., Calignano A., et al. 2003. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat. Med. 9: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidu P. S., Varvel S. A., Ahn K., Cravatt B. F., Martin B. R., Lichtman A. H. 2007. Evaluation of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition in murine models of emotionality. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 192: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bambico F. R., Gobbi G. 2008. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor and the endocannabinoid anandamide: possible antidepressant targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 12: 1347–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boger D. L., Miyauchi H., Du W., Hardouin C., Fecik R. A., Cheng H., Hwang I., Hedrick M. P., Leung D., Acevedo O., et al. 2005. Discovery of a potent, selective, and efficacious class of reversible alpha-ketoheterocycle inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase effective as analgesics. J. Med. Chem. 48: 1849–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cravatt B. F., Saghatelian A., Hawkins E. G., Clement A. B., Bracey M. H., Lichtman A. H. 2004. Functional disassociation of the central and peripheral fatty acid amide signaling systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101: 10821–10826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackie K. 2006. Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 46: 101–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn K., Johnson D. S., Cravatt B. F. 2009. Fatty acid amide hydrolase as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and CNS disorders. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 4: 763–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagar D. R., Kendall D. A., Chapman V. 2008. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase produces PPAR-alpha-mediated analgesia in a rat model of inflammatory pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 155: 1297–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maione S., Bisogno T., de Novellis V., Palazzo E., Cristino L., Valenti M., Petrosino S., Guglielmotti V., Rossi F., Di Marzo V. 2006. Elevation of endocannabinoid levels in the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey through inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase affects descending nociceptive pathways via both cannabinoid receptor type 1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 316: 969–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saghatelian A., Trauger S. A., Want E. J., Hawkins E. G., Siuzdak G., Cravatt B. F. 2004. Assignment of endogenous substrates to enzymes by global metabolite profiling. Biochemistry. 43: 14332–14339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saghatelian A., McKinney M. K., Bandell M., Patapoutian A., Cravatt B. F. 2006. A FAAH-regulated class of N-acyl taurines that activates TRP ion channels. Biochemistry. 45: 9007–9015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn K., Johnson D. S., Mileni M., Beidler D., Long J. Z., McKinney M. K., Weerapana E., Sadagopan N., Liimatta M., Smith S. E., et al. 2009. Discovery and characterization of a highly selective FAAH inhibitor that reduces inflammatory pain. Chem. Biol. 16: 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Patricelli M. P., Cravatt B. F. 1999. Activity-based protein profiling: the serine hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 14694–14699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patricelli M. P., Giang D. K., Stamp L. M., Burbaum J. J. 2001. Direct visualization of serine hydrolase activities in complex proteomes using fluorescent active site-directed probes. Proteomics. 1: 1067–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W., Blankman J. L., Cravatt B. F. 2007. A functional proteomic strategy to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized hydrolases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129: 9594–9595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung D., Hardouin C., Boger D. L., Cravatt B. F. 2003. Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 21: 687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fegley D., Gaetani S., Duranti A., Tontini A., Mor M., Tarzia G., Piomelli D. 2005. Characterization of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor cyclohexyl carbamic acid 3′-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl ester (URB597): effects on anandamide and oleoylethanolamide deactivation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilaru A., Isaac G., Tamura P., Baxter D., Duncan S. R., Venables B. J., Welti R., Koulen P., Chapman K. D. 2010. Lipid profiling reveals tissue-specific differences for ethanolamide lipids in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Lipids. 45: 863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung D., Saghatelian A., Simon G. M., Cravatt B. F. 2006. Inactivation of N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D reveals multiple mechanisms for the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids. Biochemistry. 45: 4720–4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueda N., Okamoto Y., Morishita J. 2005. N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D: a novel enzyme of the beta-lactamase fold family releasing anandamide and other N-acylethanolamines. Life Sci. 77: 1750–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly S. J., O'Shea E. M., Andersson U., O'Byrne J., Alexson S. E., Hunt M. C. 2007. A peroxisomal acyltransferase in mouse identifies a novel pathway for taurine conjugation of fatty acids. FASEB J. 21: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosendal J., Knudsen J. 1992. A fast and versatile method for extraction and quantitation of long-chain acyl-CoA esters from tissue: content of individual long-chain acyl-CoA esters in various tissues from fed rat. Anal. Biochem. 207: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golovko M. Y., Murphy E. J. 2004. An improved method for tissue long-chain acyl-CoA extraction and analysis. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1777–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohlsson C., Mohan S., Sjogren K., Tivesten A., Isgaard J., Isaksson O., Jansson J. O., Svensson J. 2009. The role of liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocr. Rev. 30: 494–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian S., Fu F., Li W., Chen Q., de Sauvage F. J. 1998. Primary role of the liver in thrombopoietin production shown by tissue-specific knockout. Blood. 92: 2189–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuter D. J., Begley C. G. 2002. Recombinant human thrombopoietin: basic biology and evaluation of clinical studies. Blood. 100: 3457–3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trauner M., Boyer J. L. 2003. Bile salt transporters: molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev. 83: 633–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.