Abstract

The mammalian alimentary tract harbors hundreds of species of commensal microorganisms that intimately interact with the host immune system. Within the gut, the immune system actively reacts with potentially pathogenic microbes, while simultaneously remaining ignorant towards the vast majority of non-pathogenic microbiota. The disruption of this delicate balance results in inflammatory bowel diseases. In this review, we describe the recent advances in our understanding of how host-microbiota interactions shape the immune system and how they affect the responses against pathogenic bacteria.

Key words: toll-like receptor, NOD, Th17, Treg, segmented filamentous bacteria

Introduction

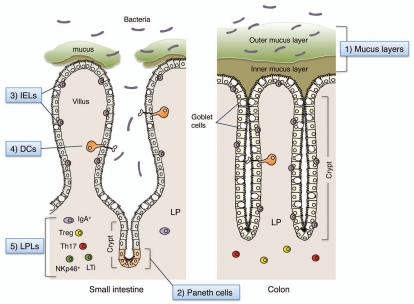

The gastrointestinal tract represents a major gateway for infection by potential pathogens including viruses, enteric bacteria, protozoa and helminth parasites. Accordingly, the gut mucosa has evolved multiple layers of protection against invading pathogens (Fig. 1). Epithelial cells are tightly sealed by tight junctions and are covered with layers of mucus produced by goblet cells.1 The intestinal epithelium contains a large population of lymphocytes known as intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), which recognize and eliminate infected or damaged epithelial cells. Paneth cells residing at the base of the crypts within the small intestine recognize microbial products via pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors and contribute to innate immunity by secreting a diverse repertoire of antimicrobial proteins.2–5 In the lamina propria (LP), dendritic cells (DCs) extend processes between the epithelial cells to continuously monitor the content of the gut lumen and activate LP lymphocytes.6 The LP contains large numbers of effector lymphocytes even in the absence of disease. These include immunoglobulin A (IgA)-producing plasma cells and γδT cells.7,8 In addition, recent studies have revealed that CD4+ T cells in the intestinal mucosa comprise significant numbers of Interleukin (IL)-17-expressing (Th17) cells.9 Furthermore, the mucosal immune system contains other unusual lymphocytes, such as IL-22-producing natural killer-like cells, which are positive for NK cell markers including NKp46 but do not have the killing activity of MHC class I negative cells,10–13 and CD4+CD3− lymphoid tissue inducer cells (LTi cells), which are known to orchestrate the development of programmed and induced intestinal lymphoid tissues.14–16 All of these cells are particularly abundant in the intestinal mucosa, even under “steady state” conditions.

Figure 1.

Multiple layers of the barrier system in the gut. (1) Mucus is secreted by goblet cells and forms two layers above the epithelial cells. In the colon, although the outer layer is loose, the inner layer is densely packed, firmly attached to the epithelium, and devoid of bacteria. In the small intestine, the mucus directly forms a soluble gel and is not attached to the epithelial cells. (2) Paneth cells are secretory epithelial cells located at the ends of the crypts within the small intestine. They secrete antimicrobial peptides and lysozyme into the crypt lumen, thereby regulating the composition of commensals and eliminating pathogens. (3) Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) represent a unique population of mostly CD8+ T lymphocytes that reside within the epithelial cell layer of the intestinal mucosa. IELs have the capacity to kill infected and distressed intestinal epithelial cells in a non-antigen specific manner to avoid the spread of pathogens. (4) A subset of lamina propria (LP) dendritic cells (DCs) actively sample luminal contents through the formation of transepithelial dendrites and transmit signals to LP lymphocytes. (5) The LP is a thin layer of loose connective tissue which lies beneath the epithelium. The LP contains large numbers of effector, as well as regulatory, lymphocytes (LPLs) even in the absence of disease.

Because the intestinal immune system is constantly “on guard”, there is the potential for deleterious responses to commensal microbiota. Bacteria colonize the intestinal lumen shortly after birth and eventually comprise approximately 1,000 species which, as a whole, constitute the “microbial flora”—an ecosystem in dynamic equilibrium. The microbial flora contributes to the digestion of food, the provision of essential nutrients and also to the prevention of propagation of pathogenic microorganisms.17,18 Thus, the relationship between the microbial flora and the host is “commensal” or, rather, “symbiotic”. To maintain this beneficial relationship, the mucosal immune system is likely to discriminate commensal organisms from pathogenic bacteria, and exert sophisticated means of active immune regulation by inducing inhibitory molecules for innate immune signaling, as well as inducing the accumulation of regulatory T (Treg) cells. The breakdown of these regulatory mechanisms causes the development of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).19,20 This review will discuss recent advances in this research field, focusing on the regulation of the innate immune system, the mechanisms of development and differentiation of functionally distinct lymphoid cell subsets in the intestine and their relationship with commensal and pathogenic organisms.

Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling in the Intestine

TLR responses in the gut.

The gut is the most frequent site of infection by pathogenic microorganisms. The innate immune system specifically recognizes molecular patterns present in microorganisms through TLRs and other pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). The activation of PRRs eventually leads to the development of antigen-specific adaptive immune responses.21 Therefore, PRR signaling governs the entire host response against invading pathogens in the intestinal mucosa, and plays a critical role in the rapid elimination of most intestinal infections without significant spread beyond the intestine. However, to avoid unnecessary inflammation, PRR responses are suppressed in the mucosa in the “steady state”. Indeed, cells isolated from the intestinal LP or epithelium, of healthy hosts are hypo-responsive to TLR stimulation.22–25 Several molecules have been identified as negative regulators of TLR signaling pathways in intestinal LP macrophages, DCs and epithelial cells.26 An example is the single immunoglobulin IL-1 receptor related molecule (SIGIRR), which contains an intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain.27,28 SIGIRR is expressed in DCs and intestinal epithelial cells and is known to inhibit IL-1 and TLR signaling by interacting with the TLR and IL-1R through its TIR domain. Mice lacking Sigirr are highly susceptible to intestinal inflammation induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) and an increased incidence of colitis-associated tumors.29 Intestinal epithelial cells from Sigirr-deficient mice show increased commensal bacteria- dependent cytokine production. Thus, SIGIRR plays a critical role in fine-tuning the modulation of TLR signaling in the intestine.

Another example is peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), a member of the nuclear receptor family, which is highly expressed in the intestinal epithelial cells.30 PPARγ has been shown to suppress expression of a subset of TLR-dependent genes by interacting with transcription factors downstream of the TLR, such as nuclear factor kappaB (NFκB).31 The presence of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a prevalent commensal anaerobic bacterium of the human intestine, leads to nuclear export of the RelA subunit of NFκB in intestinal epithelial cells. This anti-inflammatory action of B. thetaiotaomicron is mediated by PPARγ.32 Moreover, PPARγ is known to be a key receptor mediating the effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), which is widely used for the treatment of IBD patients.33

TLR-mediated responses are also counteracted by inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10. IL-10 is produced by Treg cells, DCs and macrophages in the intestine in the “steady state”. IL10-deficient mice and mice with myeloid cell-specific deficiency for STAT3, an essential signaling molecule acting downstream of the IL-10 receptor (LysM-Stat3 ko), spontaneously develop intestinal inflammation.34 In these mutant mice, LP macrophages are in a state of constitutive and aberrant activation and blockade of TLR signaling by introduction of a deficiency in TLR4 or MyD88, a critical adaptor for TLR, abrogates this intestinal inflammation,35,36 indicating that IL-10 acts on myeloid cells and induces STAT3 activation to suppress excess inflammation during TLR responses. Collectively, TLR-dependent inflammatory responses at the intestinal mucosa are kept in check by several regulatory molecules and cytokines that act on the TLR, its downstream molecules or TLR-activated cells, without which TLR-dependent excessive inflammatory responses can lead to the development of autoimmune colitis.

TLR signaling in the mucosa exerts its proper function against pathogenic microbes only when the integrity of the epithelial cell barrier is maintained. This was demonstrated by analyses of mice with intestinal epithelial-cell-specific ablation of NEMO [also called IκB kinase-γ (IKKγ)] or IKKα and IKKβ, both IKK subunits essential for NFκB activation.37,38 These conditional knockout mice spontaneously develop severe chronic intestinal inflammation. NFκB deficiency leads to apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells, impaired expression of antimicrobial peptides and translocation of bacteria into the mucosa. Intestinal inflammation is prevented by crossing these mice with Myd88-deficient mice. These results support a model in which chronic activation of TLR by continuous bacterial translocation triggers the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL1β, which causes further destruction of the epithelium and results in chronic intestinal inflammation. In other words, the break-down of the epithelial cell barrier, along with constitutive and aberrant TLR activation, may be the major underlying pathogenic mechanism of IBDs.

These findings suggest that the inhibition of TLR signaling is a prerequisite for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. However, a growing body of evidence indicates that TLR-dependent recognition of commensal bacteria is required for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Mice lacking TLR signaling components (TLR2, TLR4 or MyD88) are highly susceptible to DSS-induced intestinal inflammation.39,40 In addition, TLR9 activation through the apical surface of epithelial cells prevents aberrant NFκB activation and inhibits inflammation.41 Moreover, TLR5-mediated recognition of commensal bacteria in hematopoietic cells is required for the production of IL-22.42 IL-22 acts on epithelial cells to produce a secreted C-type lectin, RegIIIÅ, which kills Gram-positive bacteria, including vancomycin- resistant Enterococcus (VRE).2,5,42 It is also known that MyD88-dependent TLR activation in Paneth cells by commensals plays a critical role in the production of RegIIIγ and RegIIIβ.4 These studies clearly indicate that weak, but continuous, signaling via TLRs activated by commensal bacteria under normal steady-state conditions plays a crucial role in the maintenance of intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Furthermore, a very recent report shows that TLR5-deficient mice exhibit hyperphagia and features of metabolic syndrome, accompanied by changes in the composition of gut microbiota.43 Thus, TLRs at the intestinal mucosal surfaces have a variety of functions including immunity and metabolism, and further investigation is needed to understand the role and regulatory mechanisms, of TLR signaling in the intestine.

NLR-dependent responses in the intestine.

TLR-independent mechanisms for microbial recognition are also operational in the intestine; as such, cytoplasmic nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) have been well studied.44–46 NOD2 is involved in immune responses at the intestinal mucosa. NOD2 is expressed in monocytes and Paneth cells, and is a general sensor of peptidoglycan (PGN) through the recognition of muramyl dipeptide, which is common to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.45 NOD2 gene mutations are associated with increased susceptibility to Crohn disease in western (but not Asian) populations.47,48 The mutations are located in the C-terminal leucine-rich repeat region responsible for ligand recognition. In Crohn disease patients with the NOD2 mutation the expression of antimicrobial peptides, α-defensins, is reduced.49 Furthermore, Nod2-deficient mice are susceptible to oral infection by Listeria monocytogenes, with defective expression of antimicrobial α-defensins, such as Defcr-rs10 and Defcr4, in the small intestine.3 Thus, NOD2 is required for the expression of antimicrobial peptides in Paneth cells as it recognizes molecules from both commensals and pathogens in vivo.

In contrast to the restricted cellular expression of NOD2, NOD1 is expressed more ubiquitously, including intestinal epithelial cells. NOD1 detects diaminopimelate (DAP)-containing PGN, which is found mostly in the PGN of Gram-negative bacteria.50 For instance, Shigella flexneri and Escherichia coli are sensed by NOD1 in vitro. In vivo, Nod1-deficient mice are highly susceptible to infection by Helicobacter pylori.51 H. pylori-induced production of β-defensins is abolished in Nod1-/- mice, indicating that NOD1 in the intestinal epithelia plays a critical role in host defense against bacterial infection. Furthermore, NOD1 gene polymorphisms are associated with a susceptibility to inflammatory diseases such as Crohn diseases and ulcerative colitis.52 Interestingly, NOD1 signaling initiated by commensal Gram- negative bacteria is required to induce the genesis of gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), particularly of isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs).53 PGN from Gram-negative commensal bacteria, such as genus Bacteroides, is recognized by NOD1 in epithelial cells resulting in the induction of chemokines and the recruitment of cells required for the formation of ILFs. Conversely, in the absence of ILFs, the composition of the intestinal bacterial community is profoundly altered; Clostridiales and Bacteroides markedly expand, whereas the Gram-positive Lactobacillaceae are reduced, in ILF-deficient mice.53 This is perhaps because ILF is a critical organ for the generation of IgA-producing plasma cells, and defects result in changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. It has also been shown that NOD1 activation by intestinal microflora under basal conditions is required for systemic priming of the innate immune system, particularly for the activation of neutrophils.54 Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from germ-free mice show reduced killing of pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus, compared with those from conventionalized mice, confirming the systemic role of the microbiota in enhancing neutrophil function. Thus, NOD1 recognizes intestinal commensal and pathogenic bacteria and plays a critical role in the regulation, activation and organization of both local and systemic innate and adaptive immune systems.

ATP sensors in the intestine.

Adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) has recently been shown to modulate inflammation and immune cell functions.55,56 Extracellular ATP binds to, and activates, the cell-surface ionotropic (P2X) and metabotropic (P2Y) purinergic receptors, which deliver intracellular signals via ion channels or G-proteins, respectively. Signaling via P2X and P2Y is known to activate phagocytosis, chemotaxis and cytokine production by immune cells. In particular, much attention has been focused on ATP signaling via the P2X7 receptor, which co-operates with a NLR family molecule, NLRP3 (also known as CIAS1 and NALP3), to induce the assembly of a cytosolic protein complex containing ASK and Caspase-1, referred to as the “inflammasome”.57 The formation of the inflammasome is required for the activation of Caspase-1 and conversion of the immature forms of IL-1β, IL-18 and IL-33 to the mature forms. It is noteworthy that a set of SNPs located in a regulatory region of NLRP3 are associated with Crohn disease.58

ATP in the extracellular space is quickly degraded to ADP, AMP or adenosine by ATPases. However, intestinal commensal bacteria seem to provide high amounts of ATP that are beyond the capacity of host ATPases. Indeed, the ATP concentrations in the intestinal luminal contents of specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice are very high, but are very low in germ-free mice or antibiotic-treated mice.59 Moreover, high ATP concentrations can be detected in the supernatants of in vitro cultured intestinal commensal bacteria. It was shown that a unique subset of DCs, expressing high levels of the P2X and P2Y receptors, is present in the intestinal LP and produces IL-6 and TGFβ to induce Th17 cell differentiation in response to luminal ATP (discussed later).59

It is also interesting to note that the immunosuppressive activity of Treg cells is due, at least in part, to their capacity to hydrolyze extracellular ATP through the enzymatic activity of CD39 and CD73 expressed on their membranes.60,61 CD39 is an ectoenzyme that hydrolyzes ATP/UTP and ADP/UDP to the respective nucleosides, such as AMP. CD73 is an ecto-5′-nucleotidases that degrades extracellular nucleoside monophosphates to nucleosides (e.g., adenosine). Adenosine activates adenylyl cyclases by triggering the cognate Gs-protein coupled receptor A2a, which has a non-redundant role in the attenuation of inflammation and tissue damage in vivo.62 Thus extracellular ATP and its metabolites ADP, AMP and adenosine are critical factors, produced by intestinal commensal bacteria, that profoundly affect the intestinal immune system.

Regulation of the Adaptive Immune System by Commensal Bacteria

The intestinal mucosa has a unique immune system composed of a variety of lymphocytes, including IgA-producing plasma cells, IELs, γδT cells and IFNγ producing CD4+ T (Th1) cells. Furthermore, recent reports show the presence of Th17 cells, Treg cells, NKp46+ cells and LTi cells in the gut. The mechanism by which the intestinal mucosa generates diverse sets of lymphocyte populations is not fully understood. The most commonly accepted view is that such a large variety occurs as a result of the interactions between host cells and commensal bacteria, each with a distinct character. Below, we discuss how commensal bacteria provide a particular environment for the unique and well-balanced development of adaptive immune cells in the intestinal LP.

IgA-producing cells in the intestine.

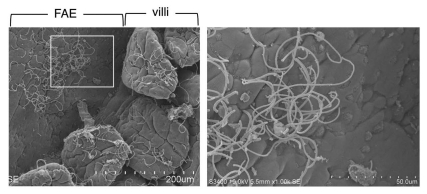

The intestinal mucosa contains many IgA-secreting plasma cells, and secreted IgA plays a critical role in host defense against pathogenic bacteria. Importantly, IgA regulates the ecological balance of commensal bacteria; in other words, IgA regulates the composition and character of intestinal microflora. For example, the lack of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which results in a defect in class-switch recombination and, thereby, a lack of IgA-producing cells in the intestine, leads to excessive anaerobic expansion in the small intestine, particularly of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) (Fig. 2 and described later in the section of “Th17 cells”).63 The addition of IgA rescues the aberrant SFB expansion in the small intestine of AID-/- mice.63 Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron is otherwise commensal to the host, but in the absence of IgA, it elicits a robust innate immune response including the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).64 Thus mucosal IgA can determine the nature of bacteria and is required for keeping commensal bacteria “commensal” to the host.

Figure 2.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). Scanning electron micrographs of the Peyer's patch area of the ileum in mice colonized with SFB. The left image shows SFB distributed on both the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the Peyer's patch and the absorptive epithelium of the villi in the ileum. The region indicated by the white square is shown at higher magnification in the right part. SFB are characterized by their long filamentous shape, with defined septa between each segment, and their attachment to epithelial cells.

The development of IgA-secreting cells is, in turn, regulated by the presence of the intestinal microflora. Germ-free mice show severe reductions in their fecal IgA levels and in the numbers of LP IgA-positive cells.7,65,66 SPF mice treated with antibiotics show similar reductions of the levels of IgA to those in germ-free mice. Thus commensal bacteria play a critical role in the provision of a particular environment for the development of IgA-producing cells. A subset of LP DCs express inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in response to microbial products and signaling via TLR.67 iNOS produces gaseous nitric oxide (NO), which then induces the expression of B-cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) in DCs. BAFF and APRIL act on B cells and promote AID expression and IgA class switching.

By using “gnotobiotic” mice, in which only certain known strains of bacteria are present, it has been shown that a set of bacterial species, such as SFB and clostridia, specifically stimulate the development of IgA-producing cells.65,66,68 IgA concentrations in the ileal contents or feces are much higher in SFB- or clostridia-associated mice than in mice associated with whole intestinal flora (conventionalized mice). Thus, certain bacterial species promote differentiation of IgA-producing cells, while others do not or may inhibit it.

Inducible Treg cells in the intestine.

Treg cells play critical roles in maintaining immunological unresponsiveness to self- antigens and in suppressing excessive immune responses deleterious to the host.69 Treg cells express the transcription factor fork-head box P3 (FoxP3), which is critical to initiating a genetic program for the suppressive functions of Treg cells.9,69 Aside from evidence that natural Foxp3+ Treg cells arise and mature in the thymus, there is mounting evidence that Foxp3+ Treg cells can develop extra-thymically under certain conditions.20,70,71 Indeed, the peripheral conversion of Foxp3-CD4+ T cells to Foxp3+ Tregs can be observed experimentally in the intestinal LP and GALT after oral exposure to antigen.72–74 These inducible Treg cells (iTreg) are believed to mediate peripheral T-cell ignorance or tolerance to antigens derived from commensal flora or those of dietary origin.

It should be noted that Foxp3-expressing Treg cells are not all the same, and different environments induce Treg cells with different characteristics. Treg cells expressing T-bet are induced, and required, for immune homeostasis under conditions of Th1 inflammation.75 Likewise, the expression of interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) in Treg cells is required for the suppression of Th2 responses,76 whereas expression of STAT3 is required for Th17 responses.77 These reports all support a model in which there is a functional plasticity within Treg cells that allows them to adapt to a particular inflammatory environment. Interestingly, in the intestine, a population of Foxp3+ Treg cells lose their expression of Foxp3 and become follicular helper T cells (Tfh cells) that interact with B cells and help their class switch recombination to IgA.78

A high percentage of Treg cells in the small and large intestine constitutively express IL-10.79 IL-10 is not expressed by thymic Treg cells, but is detectable in LP Foxp3+CD4+ T cells, suggesting that the specific environment within the gut promotes the production of IL-10 in Treg cells. IL-10 produced by Treg cells is critical for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, because Treg-specific disruption of IL-10 in mice (Foxp3-Cre × IL-10flox/flox) results in severe autoimmune colitis.80 In addition to Foxp3+CD4+ Treg cells, IL-10 is also produced by Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells, called “Tr1 cells”. Tr1 cells are abundant in the LP of small and large intestines.79 Furthermore, IELs are also known to be high producers of IL-10 in the small intestine.79 Thus, Tr1 and IL-10+ IELs contribute to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis along with Foxp3+CD4+ Treg cells.

Several DC subsets have been described that have the capacity to induce iTreg cells. In particular, there are several reports showing that a CD103 (also known as aE-integrin)-expressing DC population in the LP preferentially promotes the generation and homing of iTreg cells to the intestinal mucosa.72,73 CD103+ DCs express retinal dehydrogenase (RALDH) and produce the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RA). RA mediates the expression of the gut-homing receptors on T cells and enhances iTreg differentiation by co-operating with TGFβ.74 In addition to CD103+ DCs, CD11bhighCD11c- LP macrophages have also been shown to preferentially promote iTreg and Tr1 cell development.81 LP macrophages express high levels of IL-10 and TGFβ and preferentially induce the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Treg cells. Collectively, the preferential induction of iTreg cells and Tr1 cells at the mucosal site is attributed, at least in part, to the gut-specific presence of CD103+ DCs and CD11bhighCD11c- macrophages.

It has been shown that the intestinal microbiota has a profound effect on the induction of Treg cells. In particular, species of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria have been implicated in the induction of both Treg and Tr1 cells. For instance, treatment of mice with the probiotic mixture VSL#3 (a mixture of bifidobacteria, lactobacilli and Streptococcus salivarius) or probiotic strain Lactobacillus reuteri increased the percentage of Treg cells.82–84 Furthermore, daily ingestion of either of L. acidophilus,85 L. rhamnosus,86 L. reuteri87 or B. infantis88 results in the modification of the inflammatory status or autoimmune responses in mice; presumably by inducing Treg and Tr1 cells. In addition to these lactic acid bacteria, other bacterial taxa have been implicated in the immune suppression in the intestine. A reduction of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which belongs to the Clostridium leptum phylogenetic group, in the colon is associated with a high risk of postoperative recurrence of Crohn disease.89 Moreover, supernatants from F. prausnitzii cultures increase the production of IL-10 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Another clostridia-related bacterium, SFB, was shown to significantly affect the immune status in the terminal ileum, including induction of Treg cells.90 Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetates derived from certain species of commensal bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Bacteriodes, have also been shown to suppress intestinal inflammation. SCFAs bind G-protein coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) on neutrophils and induce several anti-inflammatory mediators.91 Furthermore, the presence of Bacteroides fragilis in the intestine suppresses inflammation through induction of IL-10-producing T cells.92 This anti-inflammatory effect of B. fragilis is mediated by polysaccharide A (PSA). PSA prevents Th1 and Th17 effector T-cell-mediated inflammation caused by Helicobacter hepaticus in the intestine. These studies indicate that specific subsets of intestinal bacteria positively regulate Treg differentiation in the intestinal mucosa.

Th17 Cells

Th17 cells constitute a subset of activated CD4+ T cells that are characterized by the production of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21 and IL-22.9,93 IL-17 acts on a broad range of immune and non-immune cells and regulates granulopoiesis, neutrophil recruitment and induction of antimicrobial peptides. IL-22 acts on epithelial cells leading to the upregulation of antimicrobial proteins and cellular proliferation.2 By producing these cytokines, Th17 cells play a critical role in the regulation of host defense against a variety of fungal and bacterial infections, such as Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Citrobacter rodentium.94–97

Th17 differentiation.

The differentiation of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells requires TGFβ and IL-6. TGFβ induces the expression of the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor RORγt, which is known to be the master transcription factor for the Th17 lineage.98 Despite its induction of RORγt, however, TGFβ alone is unable to initiate Th17 differentiation.99,100 This is because TGFβ also induces Foxp3, which is the essential transcription factor for the differentiation and function of Treg cells.69 Foxp3 inhibits RORγt-directed IL-17 expression through binding to RORγt. In the presence of IL-6, which activates STAT3 and suppresses the expression of Foxp3, the relative levels of ROR.t are increased, favoring Th17 cell differentiation.99,100 RORα plays a synergistic and somewhat redundant function with RORγt during Th17 cell polarization.101 Another transcription factor, IRF4, is also essential for Th17 cell differentiation. IRF4 is induced by T cell receptor signaling and is required for the expression of RORγt.102 The AP-1 family transcription factor, BATF, also regulates Th17 cell differentiation by binding to Th17-associated gene promoters and by maintaining RORα and RORγ expression.103 Thus, a combination of multiple transcription factors, including RORγt, RORα, STAT3, IRF4 and BATF, regulates the differentiation program for the Th17 lineage.

In addition to IL-6 and TGFβ, several cytokines further affect the differentiation of Th17 cells. For example, IL-21, which is expressed by differentiating Th17 cells themselves, mediates the expansion of Th17 cells and upregulates the expression of the IL-23 receptor via activation of STAT3.99 As a result, the differentiating Th17 cells become responsive to the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-23. In the presence of IL-23, Th17 cells further expand and mediate a fully inflammatory Th17 response.104 In fact, IL-23 is indispensable for the Th17 response required to protect mice from C. rodentium-driven colitis.97 However, in the presence of excess amounts of IL-23, Th17 cells become pathogenic and induce autoimmune diseases in mice. In a T cell transfer model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), Th17 cells are expanded in the presence of IL-23 and induce disease.104 Moreover, in humans, it has been shown that variants of the IL23R gene are linked to a susceptibility to IBDs.105 IL-1 also promotes the differentiation of Th17 cells in both mice and humans. During Th17 differentiation, cells express IL-1 receptor, and IL-1 signaling induces IRF4 and RORγt expression.106 Interestingly, a mouse strain knocked-in with an active form of NLRP3 (NLRP3-R258W), which is associated with Muckle-Wells syndrome, develops autoinflammatory disease.107 In this mouse model, inflammation is mediated by Th17 cells induced by excess IL-1β produced by the hyper-activation of inflammasomes. In the context of the role of IL-1 in Th17 differentiation, it was also shown that SIGIRR, a suppressor for TLR and IL-1R (see above), is induced in T cells during Th17 cell differentiation, and suppresses Th17 cell differentiation through the direct inhibition of IL-1-dependent signaling pathways.108 SIGIRR-deficiency leads to an increased susceptibility to Th17 cell-dependent EAE. Collectively, the differentiation and functional characteristics of Th17 cells are affected by various factors, including IL-21, IL-23 and IL-1β.

Th17 cells in the intestine.

Importantly, Th17 cells are present at high frequencies in the small and large intestinal LP in healthy animals (about 20% of CD4+ cells in the small intestine and 10% in the large intestine are IL-17+).59,98,109 In contrast, in extra-intestinal sites, only a very small proportion of CD4+TCRαβ+ T cells express IL-17 in the “steady state” (fewer than 1%).109 In germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice, the number of LP Th17 cells is greatly reduced.59,109 Therefore, the development of Th17 cells is dependent on stimulation by intestinal commensal bacteria.

How do commensal bacteria induce Th17 cells? It has been shown that TLR9-deficient mice have decreased numbers of LP Th17 cells,110 and that the in vitro differentiation of intestinal Th17 cells is enhanced by the addition of flagellin, the ligand for TLR5.111 These results suggest a potential role for TLR signaling in Th17 differentiation. In contrast, Myd88 and Trif doubly deficient mice have normal numbers of LP Th17 cells in the small and large intestines.59,109 Thus, individual TLRs may convey divergent signals that influence the differentiation of Th17 cells. Alternatively, it is possible that mice with mutations in TLR signaling may have altered intestinal microflora. Indeed, Myd88 deficiency changes the composition of the distal gut microbiota: Myd88-/- mice have a significantly lower Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio than Myd88+/− mice.112 Further studies are needed to clarify the role of TLR in the induction of intestinal Th17 cells.

In addition to TLR ligands, intestinal bacteria have been shown to provide large amounts of extracellular ATP.59 It was shown that addition of culture supernatant from intestinal commensal bacteria markedly enhances the differentiation of IL-17-expressing cells, and this Th17 differentiation is severely inhibited by the presence of ATP degrading enzymes. Furthermore, treatment of germ-free mice with ATP markedly increases the number of IL-17-producing CD4+ cells.59 Thus, extracellular ATP is one of the critical Th17-inducing factors produced by intestinal commensal bacteria. It is likely that intestinal commensal bacteria induce Th17 differentiation via several different mechanisms, including TLR signaling and ATP signaling.

Because only a very small proportion of CD4+ T cells express IL-17 in the mesenteric lymph nodes or Peyer's patches, it is likely that the differentiation of Th17 cells is induced within the LP in situ. In this context, CD70highCD11c+ cells, which are selectively present in the intestinal LP, express high levels of the P2X and P2Y receptors and induce several genes, including IL-6, IL-23, integrin-αV and integrin-β8, in response to ATP stimulation.59 Both integrin-αV and integrin-β8 are involved in the conversion of the latent form of TGFβ to the active form by triggering the degradation of latency-associated protein (LAP).113 In an in vitro culture system, CD70highCD11c+ cells preferentially induced the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells.59 Another report shows that LP CD11bhighCD11c+ cells are a Th17-inducing DC population.81 Both CD70highCD11c+ and CD11bhighCD11c+ populations express CX3CR1, a chemokine receptor that mediates the extension of DC cellular dendrites between the tight junctions of epithelial cells to take up luminal bacteria.6 Thus, it is likely that CD70high and CD11bhigh populations, at least partially, overlap with each other and both play a critical role in the Th17 differentiation in the LP by taking up antigens from the lumen.

Intestinal bacteria-mediated Th17 differentiation.

Interestingly, mice obtained from different commercial vendors have marked differences in the number of Th17 cells in their LP: C57BL/6 mice from the SPF facilities of Taconic Farms had a higher number of Th17 cells than those from the Jackson Laboratory.109 This result suggests that a specific component of the microbiota promotes Th17 cell induction. Using the 16S ribosomal RNA PhyloChip, it was found that a subset of the Firmicute-Clostridiae group, Candidatus arthromitus, commonly known as segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) were >25-fold more abundant in Taconic mice than in Jackson mice.114 SFB are yet to be cultured, commensal, spore-forming Gram-positive bacteria with segmented and filamentous morphology and are reported to colonize the intestines of numerous species.66,115–117 SFB adhere tightly to the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the Peyer's patch and the absorptive epithelium of the villi in the ileum (Fig. 2), where their abundance correlates with reduced colonization and growth of pathogenic bacteria.118 SFB are known to actively interact with the immune system: Colonization of germ-free animals with SFB leads to stimulation of secretory IgA (SIgA) production and recruitment of IELs to the gut.65,66 Notably, ingestion of SFB by Jackson SPF mice leads to the accumulation of Th17 cells,114 suggesting that the absence of SFB is responsible for the lack of Th17 cells in the small intestine of Jackson SPF mice. Furthermore, mono-colonization of SFB in germ-free mice induces a marked accumulation of Th17 cells in the small intestine.90,114 Consistently, DEFA5-transgenic mice, which express human a-defensin 5 (DEFA5) in mouse Paneth cells, exhibit loss of SFB, accompanied with decrease in the number of Th17 cells in the small intestine.119 Thus, SFB are members of the commensal microbiota that are responsible for the accumulation of Th17 cells in the small intestinal LP.

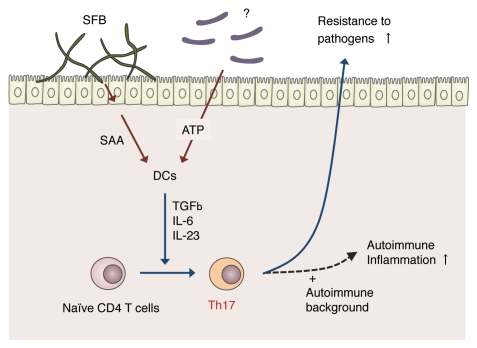

What is the mechanism by which SFB induce Th17 cells? The ATP concentrations in the ileal and colonic luminal contents of SFB mono-colonized mice were similar to those in GF mice.114 Thus, SFB-mediated Th17 cell differentiation is likely to occur through a mechanism independent of ATP-signaling. Upon colonization by SFB, the expression of genes associated with inflammation and antimicrobial proteins in the terminal ileum was observed. The highest was serum amyloid A (SAA).114 Interestingly, addition of recombinant SAA to co-cultures of naïve CD4+ T cells and LP DCs resulted in the induction of Th17 cells in vitro. These results suggest a model in which SFB colonization leads to an increase in local SAA production (perhaps produced by epithelial cells), which then acts on gut DCs to stimulate the establishment of a Th17 cell-inducing environment (Fig. 3). However, further investigation is required to establish the molecular basis underlying SFB-mediated Th17 differentiation.

Figure 3.

Model for segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB)-mediated induction of Th17 cells. Upon colonization of SFB in the small intestine, the epithelial cells release SAA. SAA is recognized by LP DCs that, in-turn, release IL-6 and IL-23, resulting in the activation of naïve CD4 T+ cells to become Th17 cells. SFB colonization and subsequent Th17 differentiation result in enhanced resistance to intestinal pathogens such as Citrobacter rodentium. However, in genetically autoimmune-prone individuals, this SFB-mediated Th17 induction may also enhance autoimmune inflammation. In addition to SFB, there may be other Th17-inducing bacterial species that produce extracellular ATP, which also activates LP DCs.

SFB colonization and the subsequent accumulation of Th17 cells are accompanied by enhanced host resistance to intestinal pathogens. Indeed, in mice colonized with Jackson microbiota alone (without SFB), and then infected with C. rodentium, which is an intestinal pathogen whose clearance by the host is known to require a Th17 immune response, a severe colon shortening and infiltration of the pathogen into the proximal colon and MLNs were observed. In contrast, in mice colonized with Jackson microbiota together with SFB, the colitis and bacterial invasion were both suppressed.114 Thus, Th17 cells present in the intestine in the “steady state” enable the host to rapidly fight against pathogenic bacteria. However, it is also possible that this SFB-mediated Th17 induction pathway may play a role in the enhancement of autoimmune inflammation, such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and IBDs, particularly in genetically autoimmune-prone individuals; this possibility should be explored further.

Enterotoxigenic strains of Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) are another type of Th17-inducing intestinal bacteria. In this case ETBF induce pathogenic Th17 cells. ETBF colonize a proportion of the human population and can cause inflammatory diarrhea in both children and adults. ETBF was found to strongly activate STAT3 in the colon, leading to a dramatic and selective Th17 response.120 In mice colonized with ETBF, colitis and colonic hyperplasia were observed. Furthermore, and very interestingly, when multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mice [heterozygous for the adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) gene] were colonized with ETBF, tumor formation was accelerated. Blocking of IL-17 or the receptor for IL-23, inhibited these ETBF-triggered pathologies.120 These results suggest that ETBF colonization induces IL-23 production in the intestine, resulting in the production of highly pathogenic Th17 cells that induce colitis and tumor formation.

Conclusion and Perspectives

We have discussed many examples of how intestinal innate and adaptive immune systems function in the induction of inflammation, the maintenance of barrier system, and the regulation of the composition of intestinal microflora. The dissection of signals through TLRs and NLRs in intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells, together with the characterization of recently identified adaptive immune cell populations, such as Treg cells and Th17 cells, has provided considerable progress in the understanding of the immune system operating in the intestinal mucosa. However, because the communication between intestinal bacteria and the mammalian immune system are bidirectional and complex, it is still difficult to comprehensively understand the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the induction of immunity, ignorance or tolerance in the intestinal mucosa. In this context, it is very interesting that a single bacterium, SFB, profoundly affects the differentiation of IgA-producing plasma cells and Th17 cells in the gut. Thus, it is important to uncover more details regarding the specific types and features of intestinal bacteria responsible for the differential induction of immune cell populations in the “steady state” and in inflammatory processes. Further investigation is clearly required into innate immune signaling and the dynamics between the mammalian immune system and the microbial flora.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Mochida Memorial Foundation, the Kato Memorial Foundation, the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science and the Kowa Life Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/gutmicrobes/article/12613

References

- 1.Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolls JK, McCray PB, Jr, Chan YR. Cytokine-mediated regulation of antimicrobial proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:829–835. doi: 10.1038/nri2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, et al. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Ismail AS, Eckmann L, Hooper LV. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20858–20863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808723105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandl K, Plitas G, Mihu CN, Ubeda C, Jia T, Fleisher M, et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci exploit antibiotic-induced innate immune deficits. Nature. 2008;455:804–807. doi: 10.1038/nature07250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA, et al. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macpherson AJ, Harris NL. Interactions between commensal intestinal bacteria and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:478–485. doi: 10.1038/nri1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan J, Chung H, Troy E, Kasper DL. Microbial colonization drives expansion of IL-1 receptor 1-expressing and IL-17-producing gamma/delta T cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella M, Fuchs A, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Otero K, Lennerz JK, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2008;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov II, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L, Hardwigsen J, et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46(+) cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46(+) cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda K, Nakano H, Yoshida H, Nishikawa S, Rennert P, Ikuta K, et al. Molecular basis for hematopoietic/mesenchymal interaction during initiation of Peyer's patch organogenesis. J Exp Med. 2001;193:621–630. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine MJ, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Kitamura H, Maruya M, Kinoshita K, Ivanov II, et al. Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity. 2008;29:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett WS, Gordon JI, Glimcher LH. Homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Cell. 2010;140:859–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouma G, Strober W. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. doi: 10.1038/nri1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory lymphocytes and intestinal inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:313–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirotani T, Lee PY, Kuwata H, Yamamoto M, Matsumoto M, Kawase I, et al. The nuclear IkappaB protein IkappaBNS selectively inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-6 production in macrophages of the colonic lamina propria. J Immunol. 2005;174:3650–3657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamada N, Hisamatsu T, Okamoto S, Sato T, Matsuoka K, Arai K, et al. Abnormally differentiated subsets of intestinal macrophage play a key role in Th1-dominant chronic colitis through excess production of IL-12 and IL-23 in response to bacteria. J Immunol. 2005;175:6900–6908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, et al. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith PD, Ochsenbauer-Jambor C, Smythies LE. Intestinal macrophages: unique effector cells of the innate immune system. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liew FY, Xu D, Brint EK, O'Neill LA. Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:446–458. doi: 10.1038/nri1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garlanda C, Riva F, Polentarutti N, Buracchi C, Sironi M, De Bortoli M, et al. Intestinal inflammation in mice deficient in Tir8, an inhibitory member of the IL-1 receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3522–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wald D, Qin J, Zhao Z, Qian Y, Naramura M, Tian L, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor-interleukin 1 receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:920–927. doi: 10.1038/ni968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao H, Gulen MF, Qin J, Yao J, Bulek K, Kish D, et al. The Toll-interleukin-1 receptor member SIGIRR regulates colonic epithelial homeostasis, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2007;26:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubuquoy L, Jansson EA, Deeb S, Rakotobe S, Karoui M, Colombel JF, et al. Impaired expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1265–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogawa S, Lozach J, Benner C, Pascual G, Tangirala RK, Westin S, et al. Molecular determinants of crosstalk between nuclear receptors and toll-like receptors. Cell. 2005;122:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly D, Campbell JI, King TP, Grant G, Jansson EA, Coutts AG, et al. Commensal anaerobic gut bacteria attenuate inflammation by regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of PPAR-gamma and RelA. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:104–112. doi: 10.1038/ni1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubuquoy L, Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Romano O, Chavatte P, et al. PPARgamma as a new therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2006;55:1341–1349. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.093484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Forster I, et al. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi M, Kweon MN, Kuwata H, Schreiber RD, Kiyono H, Takeda K, et al. Toll-like receptor-dependent production of IL-12p40 causes chronic enterocolitis in myeloid cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1297–1308. doi: 10.1172/JCI17085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Hao L, Medzhitov R. Role of toll-like receptors in spontaneous commensal-dependent colitis. Immunity. 2006;25:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, Gareus R, van Loo G, Danese S, et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2007;446:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaph C, Troy AE, Taylor BC, Berman-Booty LD, Guild KJ, Du Y, et al. Epithelial-cell-intrinsic IKKbeta expression regulates intestinal immune homeostasis. Nature. 2007;446:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature05590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Araki A, Kanai T, Ishikura T, Makita S, Uraushihara K, Iiyama R, et al. MyD88-deficient mice develop severe intestinal inflammation in dextran sodium sulfate colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Mo JH, Katakura K, Alkalay I, Rucker AN, Liu YT, et al. Maintenance of colonic homeostasis by distinctive apical TLR9 signalling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1327–1336. doi: 10.1038/ncb1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinnebrew MA, Ubeda C, Zenewicz LA, Smith N, Flavell RA, Pamer EG. Bacterial flagellin stimulates Toll-like receptor 5-dependent defense against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:534–543. doi: 10.1086/650203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meylan E, Tschopp J, Karin M. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature. 2006;442:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inohara N, Chamaillard M, McDonald C, Nunez G. NOD-LRR proteins: role in host-microbial interactions and inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:355–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fritz JH, Ferrero RL, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Weichenthal M, Schwab M, Schaffeler E, Schlee M, et al. NOD2 (CARD15) mutations in Crohn's disease are associated with diminished mucosal alpha-defensin expression. Gut. 2004;53:1658–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jehanno M, Viala J, et al. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science. 2003;300:1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG, Cardona A, Girardin SE, Moran AP, et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGovern DP, Hysi P, Ahmad T, van Heel DA, Moffatt MF, Carey A, et al. Association between a complex insertion/deletion polymorphism in NOD1 (CARD4) and susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1245–1250. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouskra D, Brezillon C, Berard M, Werts C, Varona R, Boneca IG, et al. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507–510. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, Zhou AY, Yu Y, Weiser JN. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med. 2010;16:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villani AC, Lemire M, Fortin G, Louis E, Silverberg MS, Collette C, et al. Common variants in the NLRP3 region contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:71–76. doi: 10.1038/ng285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atarashi K, Nishimura J, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Yamamoto M, Onoue M, et al. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature07240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R, et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110:1225–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;414:916–920. doi: 10.1038/414916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Suzuki K, Nagaoka H, Hiai H, Honjo T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science. 2002;298:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson DA, McNulty NP, Guruge JL, Gordon JI. IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Talham GL, Jiang HQ, Bos NA, Cebra JJ. Segmented filamentous bacteria are potent stimuli of a physiologically normal state of the murine gut mucosal immune system. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1992-2000.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Umesaki Y, Setoyama H. Structure of the intestinal flora responsible for development of the gut immune system in a rodent model. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tezuka H, Abe Y, Iwata M, Takeuchi H, Ishikawa H, Matsushita M, et al. Regulation of IgA production by naturally occurring TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells. Nature. 2007;448:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature06033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snel J, Bakker MH, Heidt PJ. Quantification of antigen-specific immunoglobulin A after oral booster immunization with ovalbumin in mice mono-associated with segmented filamentous bacteria or Clostridium innocuum. Immunol Lett. 1997;58:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)02715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Belkaid Y, Tarbell K. Regulatory T cells in the control of host-microorganism interactions (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:551–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGFb and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koch The transcritption factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeotasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat immunol. 2009;10:595. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng M. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009:458. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaudry CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009:326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsuji M. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer's patches. Science. 2009:323. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maynard CL, Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zindl CL, Rudensky AY, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3- precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:931–941. doi: 10.1038/ni1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Denning TL, Wang YC, Patel SR, Williams IR, Pulendran B. Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Di Giacinto C, Marinaro M, Sanchez M, Strober W, Boirivant M. Probiotics ameliorate recurrent Th1-mediated murine colitis by inducing IL-10 and IL-10-dependent TGFbeta-bearing regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3237–3246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karimi K, Inman MD, Bienenstock J, Forsythe P. Lactobacillus reuteri-induced regulatory T cells protect against an allergic airway response in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:186–193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Livingston M, Loach D, Wilson M, Tannock GW, Baird M. Gut commensal Lactobacillus reuteri 100–123 stimulates an immunoregulatory response. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:99–102. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torii A, Torii S, Fujiwara S, Tanaka H, Inagaki N, Nagai H. Lactobacillus acidophilus strain L-92 regulates the production of Th1 cytokine as well as Th2 cytokines. Allergol Int. 2007;56:293–301. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-06-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Foligne B, Zoumpopoulou G, Dewulf J, Ben Younes A, Chareyre F, Sirard JC, et al. A key role of dendritic cells in probiotic functionality. PLoS One. 2007;2:313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forsythe P, Inman MD, Bienenstock J. Oral treatment with live Lactobacillus reuteri inhibits the allergic airway response in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:561–569. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-821OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O'Mahony C, Scully P, O'Mahony D, Murphy S, O'Brien F, Lyons A, et al. Commensal-induced regulatory T cells mediate protection against pathogen-stimulated NFkappaB activation. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:1000112. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sokol Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008:105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lecuyer E, Mulder I, Lan A, Bridonneau C, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Happel KI, Dubin PJ, Zheng M, Ghilardi N, Lockhart C, Quinton LJ, et al. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Malley R, Srivastava A, Lipsitch M, Thompson CM, Watkins C, Tzianabos A, et al. Antibody-independent, interleukin-17A-mediated, cross-serotype immunity to pneumococci in mice immunized intranasally with the cell wall polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2187–2195. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2187-2195.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, et al. TGFbeta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR-alpha and ROR-gamma. Immunity. 2008;28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brustle A, Heink S, Huber M, Rosenplanter C, Stadelmann C, Yu P, et al. The development of inflammatory T(H)-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:958–966. doi: 10.1038/ni1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schraml BU, Hildner K, Ise W, Lee WL, Smith WA, Solomon B, et al. The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature08114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, et al. TGFbeta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Nurieva R, Kang HS, et al. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Meng G, Zhang F, Fuss I, Kitani A, Strober W. A mutation in the Nlrp3 gene causing inflammasome hyperactivation potentiates Th17 cell-dominant immune responses. Immunity. 2009;30:860–874. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gulen MF, Kang Z, Bulek K, Youzhong W, Kim TW, Chen Y, et al. The receptor SIGIRR suppresses Th17 cell proliferation via inhibition of the interleukin-1 receptor pathway and mTOR kinase activation. Immunity. 2010;32:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Sun CM, Wohlfert EA, Blank RB, Zhu Q, et al. Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity. 2008;29:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K, Jang MH, Yang BG, Jung YJ, Nishiyama M, et al. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li MO, Flavell RA. TGFbeta: a master of all T cell trades. Cell. 2008;134:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Davis CP, Savage DC. Effect of penicillin on the succession, attachment and morphology of segmented, filamentous microbes in the murine small bowel. Infect Immun. 1976;13:180–188. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.1.180-188.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Klaasen HL, Koopman JP, Van den Brink ME, Bakker MH, Poelma FG, Beynen AC. Intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria in a wide range of vertebrate species. Lab Anim. 1993;27:141–150. doi: 10.1258/002367793780810441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Angert ER. Alternatives to binary fission in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:214–224. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Heczko U, Abe A, Finlay BB. Segmented filamentous bacteria prevent colonization of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O103 in rabbits. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1027–1033. doi: 10.1086/315348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, Chu H, Karlsson-Sjoberg J, Amir E, et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:76–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wu S, Rhee KJ, Albesiano E, Rabizadeh S, Wu X, Yen HR, et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat Med. 2009;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]