Abstract

Transcriptional interference is the in cis suppression of one transcriptional process by another. Mathematical modeling shows that promoter occlusion by elongating RNA polymerases cannot produce strong interference. Interference may instead be generated by (1) dislodgement of slow-to-assemble pre-initiation complexes and transcription factors and (2) prolonged occlusion by paused RNA polymerases.

Key words: transcriptional interference, tandem promoters, RNAP pausing, gene regulation, dislodgement, TRCF, transcription factor

Transcriptional Interference as a Functional Role of Non-Coding and Antisense Transcription

The primary function of transcription by DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RNAPs) is undoubtedly the production of RNA transcripts, but it has been discovered that the process of transcription itself can regulate the independent transcription of other genes in its vicinity. An elongating RNAP may encounter DNA-bound transcription factors (TFs), structural DNA-binding proteins and other RNAPs, thereby affecting neighboring transcriptional processes. These interactions can produce transcriptional interference (TI), the direct and in cis suppression of one transcriptional process by another transcriptional process.1 Genomic tiling arrays have demonstrated that transcription occurs extensively throughout many organisms' genomes, producing many noncoding transcripts which can be partially overlapping and/or antisense to coding transcripts.2,3 Despite the discovery of many roles for non-coding RNAs, the function (if any) of most non-coding transcription remains mysterious. The many non-coding transcripts which overlap the promoters or the regulatory elements of other transcripts may be mediating regulatory interactions through TI, rather than producing a functional RNA.4

Natural Examples of Transcriptional Interference Span a Range of Organisms and Biological Functions

TI was recognized as a potentially widespread mechanism of gene regulation by pioneering studies on interfering promoters in retroviruses5 and in synthetic arrangements.6 A variety of natural instances of gene regulation by TI have since been discovered (reviewed in ref. 1), where an induced change in the activity of an interfering promoter indirectly confers an opposite change in the activity of the interfered (sensitive) promoter. Many more examples have been discovered since the review in reference 1. In S. cerevisiae, TI is involved in zinc homeostasis,7 entry into meiosis8 and variegated FLO11 expression.9 In D. melanogaster, TI has been found to function during embryonic development in establishing the mosaic expression pattern of the Hox gene Ubx.10 In mammals, TI is involved in the regulation of the β-globin genes11 and T-cell receptor recombination.12 TI has been shown to be the primary mechanism for the maintenance of latent HIV infections,13,14 and aberrant TI can cause human genetic diseases.15 Regulatory roles for TI have been found across such a variety of biological processes, in organisms from viruses to microbes to metazoans, as to suggest that gene regulation by TI is near-ubiquitous throughout life. Approximately 40% of human transcripts overlap with other transcripts,3 indicating that there are vastly more regulatory roles for TI remaining to be discovered.

Transcriptional Interference is Generated by Several Molecular Mechanisms

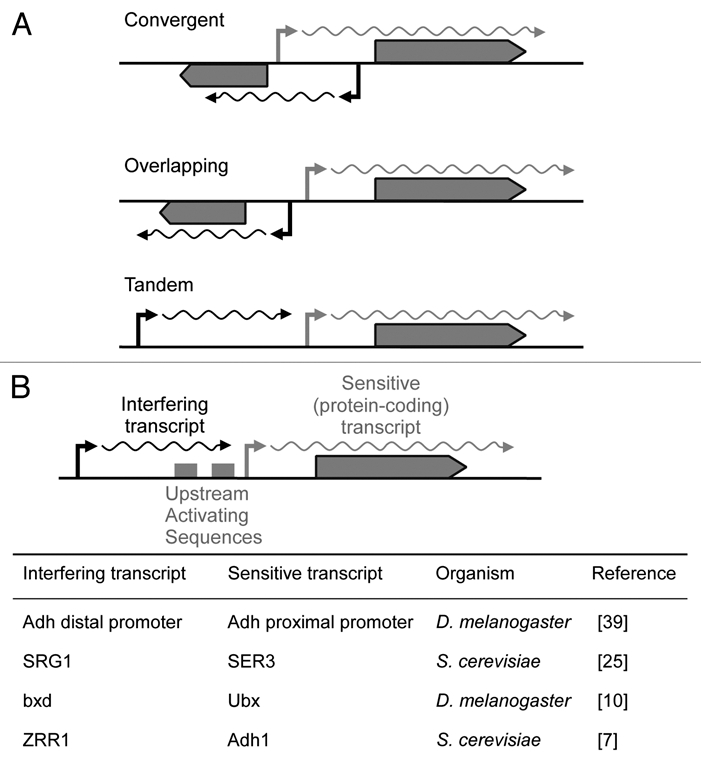

Multiple mechanisms are involved in TI, some interfering with transcriptional initiation, others interfering with transcriptional elongation. An important influence upon the potential mechanisms for a given instance of TI is the arrangement of interfering promoters, which can be convergent (face-to-face), divergent (back-to-back) or tandem (co-directional) (Fig. 1A). We will briefly describe naturally occurring mechanisms, and more detailed descriptions of mechanisms, including their discoveries, are reviewed in ref. 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Promoter arrangements which may lead to transcriptional interference. Convergent, overlapping and tandem promoter arrangements can give rise to transcriptional interference through a variety of molecular mechanisms. (B) In cis transcriptional interference between tandem promoters. Upstream promoters can interfere in cis with transcription from a downstream promoter. In some cases the upstream transcript is non-coding (SRG1, bxd and ZRR1-short), while in other cases the upstream promoter produces a full length protein-coding transcript (Adh distal promoter and ZRR1-long). All four of these studies demonstrated that transcriptional interference was produced by the in cis process of transcription over the sensitive promoter or its upstream activating sequences.

Promoter competition can result from steric hindrance due to overlapping RNAP binding sites, or from competitive recruitment of a distal enhancer element. In these cases it is the presence of the competing promoter which is responsible for interference, rather than the process of transcription itself.

Sitting duck interference is the dislodgement of RNAPs which are slow to initiate from a promoter (a ‘sitting duck’) by an elongating RNAP from another promoter.16 In prokaryotes, the sitting duck mechanism can only significantly repress a promoter if interfering RNAPs arrive more frequently than the target promoter initiates its own RNAP.17 In eukaryotes, sitting duck may be more powerful if it is possible to dislodge otherwise long-lived pre-initiation complexes (PICs) which persist for multiple rounds of initiation.18

Occlusion occurs when an RNAP passes over a promoter or TF binding sites, blocking the recruitment of RNAP or TFs by steric hindrance.19 However, as we will discuss later, the rapid rate of transcription elongation in most organisms means that occlusion is very brief, so even extremely strong interfering promoters will not produce much occlusion by elongating RNAPs.17,20

Collisions between RNAPs transcribing opposite strands result from convergent promoter arrangements. As elongating RNAP wholly envelop both strands of DNA, it is most likely that colliding RNAPs cannot both continue transcription past one another. RNAP collisions have been imaged by atomic force microscopy, showing that one elongating RNAP forces the opposing RNAP to stall and backtrack,21 however it remains uncertain whether collisions are resolved in the same way in vivo.

Transcription factor dislodgement.

Promoters whose activity is dependent on the binding of TFs can be interfered with by the dislodgement of their TFs from the DNA by passing RNAPs. The distinction between TF dislodgement, occlusion and sitting duck is subtle—all three will occur when an interfering RNAP traverses a promoter, but one of these alone may be primarily responsible for interference. TF dislodgement is clearly distinct from sitting duck when interfering RNAPs only pass over distal enhancers or activating sequences of a promoter which is not itself traversed.

Convergent Promoters Can Strongly Interfere by RNA Polymerase Collisions

Mathematical modeling shows that the probability that an RNAP can avoid colliding with an RNAP from a convergent promoter decreases exponentially with the firing rate of the interfering promoter and with the interpromoter distance.17 A study of ‘cis natural antisense transcripts’ (complementary transcripts of the same locus) in the human and mouse genomes concluded that RNAP collisions were the primary mechanism of interaction between transcripts, based upon decreasing transcript abundance with increasing overlap length, to almost zero when the overlap exceeded 2,000 nucleotides.22 Mutually strong and widely separated convergent promoters will have great difficulty producing full length transcripts due to collisions. More functional convergent promoter arrangements, where successful transcription is feasible and subject to regulation by TI, include (1) closely spaced convergent promoters and (2) widely spaced convergent promoters where at any time one promoter is considerably stronger.

The first arrangment has been observed in the lysis/lysogeny switches of coliphages 186 and λ, where interfering convergent promoters are sufficiently close together that collisions between elongating RNAPs have relatively minor (≤2-fold) contributions to TI, as determined by experimental variation in interpromoter distance, quantitative measurements and mathematical modeling.17,20

The second arrangement is demonstrated by the regulation of meiotic entry in S. cerevisiae by TI between the sense and antisense transcripts of the IME4 gene, produced from promoters separated by ∼2,000 nucleotides.8 In haploids, the antisense IME4 transcript is driven by a strong promoter and acts in cis to repress transcription from the weaker sense promoter. In diploids, the antisense promoter is repressed by the diploid specific a1/α2 heterodimer, permitting derepressed sense transcription. Critically, the artificial insertion of an extremely strong sense promoter drives high levels of sense transcription and eliminates antisense transcription in haploids. This in cis interference is therefore mutual and competitive, with only the stronger promoter producing significant levels of transcription—the behavior expected of TI by RNAP collisions.

Transcriptional Interference between Tandem Promoters is Not Satisfactorily Explained by RNAP Collisions or Occlusion by Elongating RNAP

TI has also been repeatedly observed between tandem promoters, often with an upstream promoter producing a non-coding transcript which interferes with the activity of a downstream promoter of a protein coding gene. Several studies have found that a naturally in cis interfering transcript fails to produce interference when expressed in trans and, combined with other mechanistic experiments, have concluded that interference of a downstream promoter is produced in cis by the process of transcription across the promoter or its upstream activating sequences (UAS) (Fig. 1B). For clarity, the table within Figure 1B contains only studies that have strictly proven that repression occurs in cis and omits many other potential but not definite in cis cases of TI.

Transcription across a promoter or a UAS is not necessarily repressive, so how do these particular upstream transcripts produce TI? Promoter competition can be disregarded in ref. 7, 25 and 39, which all demonstrated that early termination of the interfering transcript abolished TI. TI by collisions between tandem promoters can also be disregarded, as co-directional RNAPs cooperate upon collision; a trailing RNAP will assist a leading RNAP in exiting a pause or in displacing a DNA-bound obstacle.23,24 TI by dislodgement of RNAPs yet to initiate from a promoter (sitting duck) is only substantial when the interfering promoter is much stronger than the sensitive promoter;17 yet, of the studies in Figure 1B, none contain any data that indicates that the interfering promoter is significantly stronger than the sensitive promoter.

Studies of TI at the SER3 and Adh1 promoters (Fig. 1B) observed that TI caused a reduction in TF occupancy and, together with the study of Ubx interference, suggested that interfering RNAPs occlude TF access.7,10,25,26 Yet, when considered quantitatively, strong TI cannot be explained by occlusion due to elongating RNAPs, because elongation is so rapid. In vivo measurements of elongating RNAP have observed speeds of 25–65 nucleotides/second in E. coli,23 20 nucleotides/second in D. melanogaster27 and 70 nucleotides/second in humans.28 Since the footprint of an elongating RNAP is rather short (length of elongating RNAPII in S. cerevisiae is 43 nucleotides,24 or 35 nucleotides in E. coli29), an elongating RNAP will pass over a given point on the template DNA in 0.5–2 seconds. Therefore a promoter or transcription factor binding site will only suffer substantial occlusion if interfering RNAPs arrive every few seconds, a rate only produced by the most exceptionally strong promoters.

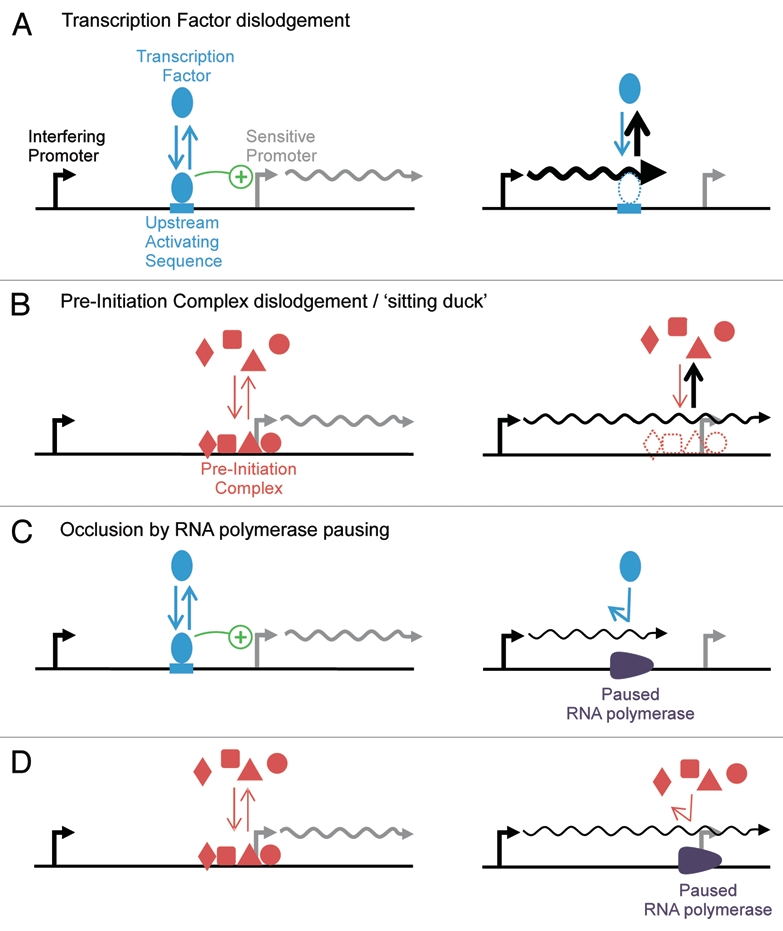

Dislodgement of Transcription Factors and Slow-to-Assemble Pre-Initiation Complexes Can Produce Transcriptional Interference

Interfering RNAPs can hinder TF binding at a promoter or UAS by either occlusion (preventing TF binding) or dislodgement (removing bound TFs). Dislodgement of TFs by interfering RNAPs can be considered as an increase in the effective dissociation rate of the TF, from the intrinsic dissociation rate koff to a compound rate koff + φ, where φ is the rate of arrival of interfering RNAP, equal to the initiation rate of the interfering promoter less any attenuation. To hinder TF binding φ must be much larger than koff, so as to substantially increase the net dissociation rate and thereby reduce TF binding (Fig. 2A). A variety of intrinsic TF dissociation rates have been measured in vivo by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), obtaining half-maximal turnover times (≈0.7 × koff) ranging from less than 1 second30 to 40 seconds.31 Absolute transcriptional initiation rates . have been rarely measured, but a study of the S. cerevisiae his3 gene observed that one mRNA was produced every 140 seconds, and the authors estimated the maximum possible initiation rate in S. cerevisiae as one transcript per 6–8 seconds.32 Comparing these measurements of koff and φ indicates that it is feasible slow-binding transcription factors might be effectively removed via frequent dislodgement by RNAPs arriving from a strong interfering promoter. However, it is likely that many TFs exist in a much more rapid equilibrium with their binding sites, and their dislodgement by the occasional interfering RNAP coming from a weak upstream promoter would be insignificant in comparison to the intrinsic turnover rates.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms for strong transcriptional interference between tandem promoters. Association/dissociation reaction rates are represented by arrow thickness; promoter activity is represented by transcript thickness. (A) Transcription Factor (TF) binding can be hindered by frequent dislodgement by interfering RNA polymerases (RNAPs), provided that interfering RNAPs arrive significantly faster than the TFs intrinsic dissociation rate; therefore, this may require a strong interfering promoter. (B) Promoters which rely upon a stable, slow-to-assemble Pre-Initiation Complex (PIC) for multiple rounds of PIC-assisted reinitiation can be repressed by PIC dislodgement. Interfering transcription must reach the sensitive promoter for PIC dislodgement, but does not require a strong interfering promoter. Elongating RNAPs transcribe too rapidly to produce substantial occlusion, but RNAPs can pause over upstream activating sequences (C) or the sensitive promoter (D) to prolong occlusion and produce strong transcriptional interference, even from a relatively weak interfering promoter.

Strong TI could also result when RNAPs traverse a promoter which relies heavily on pre-initiation complex (PIC)-assisted reinitiation, where a complex of transcription factors remain stably associated throughout multiple rounds of transcription initiation.18 A collectively long-lived initiation complex could be composed of TFs with rapid individual turnover and yet could be vulnerable to interfering RNAPs which dislodge the entire slow-to-assemble PIC (Fig. 2B). This is the eukaryotic extension of the concept of sitting duck interference:16,17 prokaryotic promoters can be repressed if interfering RNAPs arrive more rapidly than the sensitive promoter initiates its own stationary RNAP (the “sitting duck”), but the persistence of PICs at some eukaryotic promoters constitutes a much longer lived “sitting duck,” which could therefore be repressed by a comparatively weak upstream promoter.

Instances of TI where interfering RNAPs pass over a promoter or its UASs (see schematic in Fig. 1B) might therefore be explained in two possible scenarios: (1) TF dislodgement: the target TFs have particularly slow binding kinetics and the interfering promoter is rather strong (Fig. 2A) or (2) PIC dislodgement/sitting duck: interfering RNAPs do not only dislodge TFs at UASs, but entirely remove the pre-initiation complex from the promoter, where the PIC is slow-to-assemble and full transcriptional activity is only possible when the PIC persists for multiple rounds of PIC-assisted reinitiation (Fig. 2B). It is feasible that both of these scenarios may be abundant throughout the genomes of many species, allowing their pervasive non-coding transcription2,3 to act as a regulator of other transcriptional units.

Despite these potential mechanisms, a satisfactory explanation is still lacking for instances where strong TI is caused by a relatively weak interfering transcript which only passes over UASs and not the sensitive promoter, such as the proposed repression of the SER3 promoter by SRG1.25,26 While the authors did not directly determine the relative strengths of the SRG1-SER3 promoters, using a fusion where SRG1 interferes with the GAL7 promoter and reduces TF binding, a single northern probe was utilized to identify both the interfering and the sensitive transcript, revealing that the interfering transcript was substantially weaker than its target, which it was able to potently repress.25 Unless this quantitation is distorted by a highly unstable SRG1 transcript, the question is raised as to how, in the natural SRG1-SER3 promoter arrangement, can a weak transcriptional process potently interfere with a stronger downstream promoter, by only passing over its UASs?

RNA Polymerases Can Pause to Prolong Occlusion

Single molecule studies in vitro and in vivo reveal that RNAP elongation in both E. coli and humans is frequently interrupted by pauses of durations up to minutes.28,33,34 Thus, while an elongating RNAP may only occlude a site for seconds, if an RNAP pauses over a promoter or TF binding site it could cause radically stronger occlusion (Fig. 2C). Such behavior was recently observed in a study of TI in coliphage λ, where multiple pause sites are naturally arrayed over a sensitive promoter, enabling RNAPs from an interfering promoter to strongly interfere by prolonged occlusion.20 In the studies in Figure 1B, a promoter is strongly repressed by upstream tandem transcription over its UASs or the promoter itself, but in all cases there is no evidence to suggest that the upstream interfering promoter is notably stronger than the sensitive downstream promoter. We have explained how interference by TF dislodgement is only significant subject to particular properties of the target TFs and promoter, and does not appear feasible in the cases where only the UASs are traversed by a moderate flow of interfering RNAP.10,25,26 Prolonged occlusion of UASs by paused RNAPs is a potential explanation for these otherwise puzzling observations.

Transcriptional Interference by RNA Polymerase Pausing is Evolvable and Allows Regulatory Flexibility

Occlusion by RNAP pausing is the most highly evolvable of TI mechanisms. Pause locations and durations are evolvable because they are sequence-dependent, and thus in instances where TI serves a functional regulatory purpose, the extent of TI by RNAP pausing can be fine-tuned throughout evolution to meet the regulatory needs of the system. Critically, the magnitude of TI by RNAP pausing can be adjusted independently of the strength of the interfering and target promoters, which is not possible for other mechanisms, to the extent that arbitrarily powerful TI does not even require that the interfering promoter be stronger than the sensitive promoter.20 The regulatory possibilities of TI by RNAP pausing are substantial, since pause duration can be dynamically regulated by RNAP-interacting factors. For example, the N protein of coliphage λ modifies only elongating RNAPs which have transcribed an “N utilization site,” rendering the RNAP pause and termination resistant. Expression of N was observed to increase the read-through of interfering transcription while simultaneously reducing TI, demonstrating that occlusion by RNAP pausing possesses regulatory flexibility lacking from other mechanisms. These findings add to the growing understanding of the roles of RNAP pausing in controlling gene expression.35–37

Finally, we will note an instance of TI by RNAP pausing in mammals. The mouse FPGS gene is expressed from two tandem promoters to produce one of two isoforms in different tissues, with transcription from the upstream promoter repressing the downstream promoter. A study of TI between the FPGS promoters observed a particularly high-density of RNAPII elongation complexes residing over the downstream promoter, and concluded that repression was caused by occlusion.38 The authors also noted that RNAP accumulation coincided with the start of the downstream promoter, suggesting that RNAP transit was slowed over the repressed promoter. We consider it evident that the slowing or pausing of RNAP transit is responsible for strong TI via prolonged occlusion, providing an example where occlusion by RNAP pausing controls tissue specific gene expression in a mammal.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant GM062976.

Abbreviations

- TI

transcriptional interference

- RNAP

DNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- TF

transcription factor

- PIC

pre-initiation complex

- UAS

upstream activating sequence

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/transcription/article/13511

References

- 1.Shearwin KE, Callen BP, Egan JB. Transcriptional interference-a crash course. Trends Genet. 2005;21:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JM, Edwards S, Shoemaker D, Schadt EE. Dark matter in the genome: Evidence of widespread transcription detected by microarray tiling experiments. Trends Genet. 2005;21:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faghihi MA, Wahlestedt C. Regulatory roles of natural antisense transcripts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen BR, Lomedico PT, Ju G. Transcriptional interference in avian retroviruses—implications for the promoter insertion model of leukaemogenesis. Nature. 1984;307:241–245. doi: 10.1038/307241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proudfoot NJ. Transcriptional interference and termination between duplicated alpha-globin gene constructs suggests a novel mechanism for gene regulation. Nature. 1986;322:562–565. doi: 10.1038/322562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird AJ, Gordon M, Eide DJ, Winge DR. Repression of ADH1 and ADH3 during zinc deficiency by Zap1-induced intergenic RNA transcripts. EMBO J. 2006;25:5726–5734. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hongay CF, Grisafi PL, Galitski T, Fink GR. Antisense transcription controls cell fate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2006;127:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bumgarner SL, Dowell RD, Grisafi P, Gifford DK, Fink GR. Toggle involving cis-interfering noncoding RNAs controls variegated gene expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petruk S, Sedkov Y, Riley KM, Hodgson J, Schweisguth F, Hirose S, et al. Transcription of bxd noncoding RNAs promoted by trithorax represses Ubx in cis by transcriptional interference. Cell. 2006;127:1209–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu X, Eszterhas S, Pallazzi N, Bouhassira EE, Fields J, Tanabe O, et al. Transcriptional interference among the murine beta-like globin genes. Blood. 2007;109:2210–2216. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abarrategui I, Krangel MS. Noncoding transcription controls downstream promoters to regulate T-cell receptor alpha recombination. EMBO J. 2007;26:4380–4390. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han Y, Lin YB, An W, Xu J, Yang HC, O'Connell K, et al. Orientation-dependent regulation of integrated HIV-1 expression by host gene transcriptional readthrough. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenasi T, Contreras X, Peterlin BM. Transcriptional interference antagonizes proviral gene expression to promote HIV latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Gobbi M, Viprakasit V, Hughes JR, Fisher C, Buckle VJ, Ayyub H, et al. A regulatory SNP causes a human genetic disease by creating a new transcriptional promoter. Science. 2006;312:1215–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1126431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callen BP, Shearwin KE, Egan JB. Transcriptional interference between convergent promoters caused by elongation over the promoter. Mol Cell. 2004;14:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sneppen K, Dodd IB, Shearwin KE, Palmer AC, Schubert RA, Callen BP, et al. A mathematical model for transcriptional interference by RNA polymerase traffic in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieci G, Sentenac A. Detours and shortcuts to transcription reinitiation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:202–209. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adhya S, Gottesman M. Promoter occlusion: Transcription through a promoter may inhibit its activity. Cell. 1982;29:939–944. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer AC, Ahlgren-Berg A, Egan JB, Dodd IB, Shearwin KE. Potent transcriptional interference by pausing of RNA polymerases over a downstream promoter. Mol Cell. 2009;34:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crampton N, Bonass WA, Kirkham J, Rivetti C, Thomson NH. Collision events between RNA polymerases in convergent transcription studied by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5416–5425. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osato N, Suzuki Y, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. Transcriptional interferences in cis natural antisense transcripts of humans and mice. Genetics. 2007;176:1299–1306. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epshtein V, Nudler E. Cooperation between RNA polymerase molecules in transcription elongation. Science. 2003;300:801–805. doi: 10.1126/science.1083219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeki H, Svejstrup JQ. Stability, flexibility and dynamic interactions of colliding RNA polymerase II elongation complexes. Mol Cell. 2009;35:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martens JA, Laprade L, Winston F. Intergenic transcription is required to repress the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SER3 gene. Nature. 2004;429:571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature02538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martens JA, Wu PY, Winston F. Regulation of an intergenic transcript controls adjacent gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2695–2704. doi: 10.1101/gad.1367605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardehali MB, Yao J, Adelman K, Fuda NJ, Petesch SJ, Webb WW, et al. Spt6 enhances the elongation rate of RNA polymerase II in vivo. EMBO J. 2009;28:1067–1077. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darzacq X, Shav-Tal Y, de Turris V, Brody Y, Shenoy SM, Phair RD, et al. In vivo dynamics of RNA polymerase II transcription. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:796–806. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krummel B, Chamberlin MJ. Structural analysis of ternary complexes of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Deoxyribonuclease I footprinting of defined complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90918-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharp ZD, Mancini MG, Hinojos CA, Dai F, Berno V, Szafran AT, et al. Estrogen-receptor-alpha exchange and chromatin dynamics are ligand- and domain-dependent. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4101–4116. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpova TS, Kim MJ, Spriet C, Nalley K, Stasevich TJ, Kherrouche Z, et al. Concurrent fast and slow cycling of a transcriptional activator at an endogenous promoter. Science. 2008;319:466–469. doi: 10.1126/science.1150559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer V, Struhl K. Absolute mRNA levels and transcriptional initiation rates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5208–5212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adelman K, La Porta A, Santangelo TJ, Lis JT, Roberts JW, Wang MD. Single molecule analysis of RNA polymerase elongation reveals uniform kinetic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13538–13543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212358999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuman KC, Abbondanzieri EA, Landick R, Gelles J, Block SM. Ubiquitous transcriptional pausing is independent of RNA polymerase backtracking. Cell. 2003;115:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Core LJ, Lis JT. Transcription regulation through promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2008;319:1791–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1150843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landick R. The regulatory roles and mechanism of transcriptional pausing. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1062–1066. doi: 10.1042/BST0341062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajala T, Hakkinen A, Healy S, Yli-Harja O, Ribeiro AS. Effects of transcriptional pausing on gene expression dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:1000704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Racanelli AC, Turner FB, Xie LY, Taylor SM, Moran RG. A mouse gene that coordinates epigenetic controls and transcriptional interference to achieve tissuespecific expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:836–848. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01088-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbin V, Maniatis T. Role of transcriptional interference in the Drosophila melanogaster Adh promoter switch. Nature. 1989;337:279–282. doi: 10.1038/337279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]