Abstract

Background

Over half a million U.S. women and more than 100,000 men are treated for injuries from intimate partner violence (IPV) annually, making IPV perpetration a major public health problem. However, little is known about causes of perpetration across the life course.

Purpose

This paper examines the role of “stress sensitization,” whereby adult stressors increase risk for IPV perpetration most strongly in people with a history of childhood adversity.

Methods

The study investigated a possible interaction effect between adulthood stressors and childhood adversities in risk of IPV perpetration, specifically, whether the difference in risk of IPV perpetration associated with past-year stressors varied by history of exposure to childhood adversity. Analyses were conducted in 2010 using de-identified data from 34,653 U.S. adults from the 2004–2005 follow-up wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.

Results

There was a significant stress sensitization effect. For men with high-level childhood adversity, past-year stressors were associated with an 8.8% increased risk of perpetrating compared to a 2.3% increased risk among men with low-level adversity. Women with high-level childhood adversity had a 14.3% increased risk compared with a 2.5% increased risk in the low-level adversity group.

Conclusions

Individuals with recent stressors and histories of childhood adversity are at particularly elevated risk of IPV perpetration; therefore, prevention efforts should target this population. Treatment programs for IPV perpetrators, which have not been effective in reducing risk of perpetrating, may benefit from further investigating the role of stress and stress reactivity in perpetration.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a consequential public health problem, with over half a million women and more than 100,000 men requiring medical treatment for injuries sustained from IPV in the U.S. annually.1 Victimization is associated with substantial physical and mental illness, including injury, asthma, chronic pain, sexually transmitted infections, depression, suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder, and death.2–7 A comprehensive understanding of the etiology of IPV perpetration is critical to inform prevention efforts.

Considerable evidence links IPV perpetration in adulthood with childhood adversity, especially exposure to violence, including physical abuse8–11 and witnessing IPV. 12–14 Although several theories explain how exposure to childhood adversities increases risk of IPV perpetration in adulthood,12, 14–18 the theory of “stress sensitization,” whereby adverse childhood events physiologically and psychologically sensitize individuals to hyper-reactivity to later stressors, has not been examined.

Heightened reactivity to stress is a potential mechanism linking childhood adversities with IPV perpetration. Evidence indicates that childhood adversities increase vulnerability to subsequent stress, through sensitization of the central nervous system,19 dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis,20, 21 and effects on the prefrontal cortex that have an impact on the threat-appraisal response system,22 thereby increasing liability to mood and anxiety disorders following adult stressful life events.23–26 Childhood adversities are also associated with increased negative emotional reactivity to daily life stressors, reactivity that persists into adulthood.27, 28 Although to date stress sensitization effects have been examined almost entirely in relation to mood and anxiety disorders, the heightened emotional reactivity associated with childhood adversities may also increase risk of IPV perpetration following adulthood stressors. Several studies have found an association between stressful events in adulthood and IPV perpetration,29–34 although most have been clinic or convenience samples, or restricted to specific ages.

This paper tests a stress sensitization model of IPV perpetration by testing whether there is an interaction between childhood adversities and past-year stressful life events in increasing risk of IPV perpetration in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large, nationally representative survey of U.S. adults.

Methods

Data

The NESARC used a multistage sampling design that yielded a representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized population aged ≥ 18 years residing in the U.S. at Wave 1 in 2001–2002 (81% response).35, 36 This 2010 study uses data primarily from the Wave 2 follow-up interview (n=34,653, response rate, 86.7%; cumulative response, 70.2%),36 conducted in 2004–2005, which assessed IPV perpetration, childhood adversities, and past-year stressors. For respondents present in Wave 2, data from Wave 1 regarding childhood family structure, which was not assessed at Wave 2, are included. Information about the population and sample frame has been published elsewhere.35

Measures

Perpetration of intimate partner violence

Respondents who were married or in a romantic relationship in the past year were asked about use of physical force with their partner. Six questions from the Conflict Tactics Scales,37 which have been validated in general population samples,38 asked about respondents’ use of force with their partners and their partners’ use of force with them in the past year. Respondents were coded as perpetrators if they had: (1) pushed, grabbed, or shoved; (2) slapped, kicked, bitten, or punched; (3) threatened with a weapon; (4) cut or bruised; (5) forced sex; or (6) injured their partner enough to require medical care.38, 39 Respondents were considered to have perpetrated serious IPV if they had pushed, grabbed or shoved their partner once a month or more often, or had slapped, kicked, bitten, or punched their partner more than once, or had ever threatened with a weapon, cut or bruised, forced sex, or injured enough to require medical care.39 IPV victimization was coded from responses about respondents’ partners’ use of force with them.

Although perpetration was assessed only in respondents in a past-year relationship, all respondents were included in the analyses in case the likelihood of being in a relationship was influenced by adversities or stressors. However, to facilitate comparisons with other studies, this study reports prevalence of perpetration among respondents in a relationship.

Childhood adversities before age 18 years

Abuse and neglect

Physical abuse was frequency of caregivers pushing, hitting, or bruising the respondent.37 Respondents in the highest 10% were scored “high,” those with lower levels were scored “some,” and those without physical abuse were scored “none.” Emotional abuse was similarly measured with three questions about caregivers making hurtful comments or threatening violence, and grouped in 3 levels like physical abuse.40 Physical neglect was measured by summing responses to five questions regarding frequency of different types of neglect, and also grouped in 3 levels.41 Emotional neglect was measured with five questions regarding types of support from family.42 Respondents scoring in the lowest 10% of this scale were coded as having high neglect, those in the next 25%, medium neglect, and the remaining, no neglect. Respondents were considered to have witnessed serious IPV if their mother’s partner: fairly often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped or threw something at her; sometimes, fairly often, or very often kicked, bit, or punched her; or ever repeatedly hit her, or threatened or hurt her with a weapon. Respondents were considered to have witnessed mild IPV if they witnessed any lesser degree of IPV.37, 38 Sexual abuse was assessed with four questions about unwanted sexual experiences43 and a question about sexual molestation before age 18 years, and was coded as present or absent.

Family dysfunction and adversities

Because younger age at experiencing events is associated with more serious sequelae,44, 45 events were coded as first occurring either before age 12 years or in adolescence, ages 12–18 years, when this information was available. Events for which age was unavailable were coded simply present or absent. Parents’ divorce or separation was coded as not occurring in childhood, occurring before age 12 years, or from ages 12 to 18 years. Four circumstances regarding parents or other adults living in the home during childhood were each coded dichotomously: problem drinking, problem drug use, imprisonment, and mental illness, including attempted or completed suicide. Problem drinking or drug use was defined for respondents to mean substance use that led to physical, emotion, interpersonal, legal, or work problems, or involved a lot of time spent drunk, high, or hung over. Poverty was measured dichotomously based on receipt of government aid.

Traumatic events

Two types of violence-related events were each coded as occurring before age 12 years, occurring from ages 12 to 18 years, or not occurring in childhood: violent victimization in the community including assault, mugging, stalking, kidnapping, and terrorism; and witnessing someone killed or seeing a dead body.

Adulthood past-year stressful life events

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV assessed a wide range of stressful life events occurring in the year before the interview.36 Events that could logically be sequelae of IPV perpetration, such as trouble with the law, were excluded. Economic stressors included: experiencing a financial crisis; being fired or laid off; being unemployed for more than 1 month; having family income below 150% of the poverty line (lowest level) or below U.S. median income (middle level), adjusted for family size; and changes in job responsibilities. Interpersonal stressors included: serious problems with a neighbor, friend or relative; problems with a boss or coworker; death of a family member or close friend; and having a child aged <5 years at home. Crime-related stressors included: being mugged or attacked; seeing someone killed or seeing a dead body; being the victim of theft; and intentional damage to respondent’s property. Other stressors included experiencing a serious illness, accident or natural disaster; moving or having someone new move in; and having any other extremely stressful experience as defined by respondents.

Analyses

To investigate the effects of childhood adversities on risk of adulthood perpetration, a single multivariate log-linear model with IPV perpetration as the dependent variable and all childhood adversities as independent variables was created. Because childhood adversities may differ in the average strength of their association with future perpetration, a childhood adversity score was created using the risk ratio from this model rounded to one decimal place as a multiplier for each adversity, which permitted different types of adversities to have stronger or weaker relationships with perpetration. Next, to examine the impact of past-year stressors on risk of perpetration, a single multivariate log-linear model with perpetration as the dependent variable and all adulthood stressors as independent variables was created. Because stressors may also differ in their average effects on perpetration, an adulthood stressor score was created using the risk ratio of perpetration from this model rounded to one decimal place as a multiplier for each stressor, permitting stressors to vary in the strength of their association with perpetration.

To test the theory of stress sensitization, a model with perpetration as the dependent variable and childhood adversity score, adulthood stressor score, and an interaction between adversity and stressor as independent variables was created. To facilitate comparison of risk differences across levels of childhood adversity and adulthood stressors, respondents were grouped into quartiles of childhood adversity and adulthood stressors. According to stress-sensitization theory, the difference in risk of perpetrating IPV in adults with high versus low levels of adulthood stressors would be larger for individuals sensitized to stress by childhood adversity. The interaction between adversity and stressors was therefore assessed on the additive scale.46 First, an adjusted risk of perpetrating for each combination of the four adversity and four stressor levels was calculated, yielding a 4-by-4 table. Next, a chi-square test of this table was conducted to see if overall difference in risk of perpetrating from stressors differed significantly across quartiles of childhood adversity. Finally, using respondents in the lowest childhood adversity quartile as the reference group, risk differences were calculated comparing the highest quartile of adulthood stressors with the lowest quartile of stressors. This calculation was then repeated for each of the other levels of childhood adversity and these risk differences were compared with the reference group using Student’s t-tests.

All analyses were conducted separately for men and women, and adjusted for age at interview, measured continuously, and race/ethnicity, which NESARC classified as follows: Hispanic, or non-Hispanic: black, American Indian/Native Alaskan, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, or white. Two-sided tests with a p-value<0.05 were used to determine significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using five sets of imputed data (iveWare 2009).47, 48 Variables were missing no more than 1.1% of responses. Analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software (release 9.0.3) to account for the nested sampling design of the NESARC study, which may result in correlated responses, to weight the data to reflect the U.S. population, and to combine results from the five imputed data sets.35

Results

Among respondents married or in a romantic relationship in the past year (76.2% of women and 85.6% of men), women endorsed past-year IPV perpetration more often than men, with 7.0% (SE=0.3) of women and 4.2% (SE=0.2) of men self-reporting perpetration ( , P<0.001). Serious IPV perpetration was also more common among women than men, with 2.2% (SE=0.1) of women and 1.2% (SE=0.1) of men endorsing serious perpetration ( , P<0.001). Men and women reported similar levels of perpetrating the most-severe acts: 0.55% (SE=0.08, n=67) of men and 0.69% (SE=0.08, n=115) of women reported cutting or bruising their partner, and 0.41% (SE=0.07, n=56) of men and 0.34% (SE=0.06, n=60) of women reported forcing sex.

When asked about their own IPV victimization, men and women reported similar levels, with 5.8% (SE=0.25) of men in relationships reporting victimization and 5.5% (SE=0.24) of women reporting victimization ( , P=0.29). Women were more likely to report being cut or bruised than were men. Among perpetrators, more men than women reported IPV victimization, with 73.9% (SE=2.2) of male perpetrators reporting victimization and 56.1% (SE=1.8) of female perpetrators reporting victimization ( , P<0.001)

Every adverse childhood circumstance was significantly more common among perpetrators than nonperpetrators except for parent’s mental illness and parent’s divorce among men (Table 1). For perpetrators, levels of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, witnessing IPV, and having a parent imprisoned were approximately double those of nonperpetrators. Prevalence of every adult financial, relationship, and crime stressor was elevated among perpetrators, with the exception of seeing someone killed/seeing a dead body and other trauma to a loved one among men (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of adverse childhood circumstances and adult stressors by perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV), U.S. men and women aged ≥ 20 years (N=34 653)

| Men (n=14 564) | Women (n=20 089) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not perpetrate IPV (n=14 049) | Perpetrated IPV (n=515) | Did not perpetrate IPV (n=18 921) | Perpetrated IPV (n=1 168) | |

| %(SE) | ||||

| Adverse childhood circumstances | ||||

| Abuse and neglect | ||||

| Physical abuse | 11.2 (0.4) | 24.9 (2.1)*** | 10.6 (0.3) | 23.9 (1.5)*** |

| Witness IPV | 13.5 (0.4) | 29.4 (2.3)*** | 15.3 (0.4) | 29.9 (1.6)*** |

| Sexual abuse | 5.4 (0.3) | 13.1 (1.7)** | 16.1 (0.4) | 32.8 (1.6)*** |

| Emotional abuse | 9.4 (0.3) | 17.5 (1.9)*** | 11.1 (0.3) | 21.6 (1.5)*** |

| Emotional neglect | 9.9 (0.3) | 15.4 (2.0)* | 12.2 (0.3) | 17.1 (1.4)*** |

| Physical neglect | 9.4 (0.4) | 17.6 (1.9)*** | 10.0 (0.3) | 16.1 (1.3)*** |

| Problems of parent/adult in home | ||||

| Problem alcohol user | 20.1 (0.5) | 30.0 (2.7)** | 22.9 (0.5) | 33.4 (1.8)*** |

| Problem drug user | 4.6 (0.2) | 7.1 (1.3)* | 4.5 (0.2) | 11.5 (1.1)*** |

| Imprisoned | 6.9 (0.3) | 13.6 (1.9)** | 6.6 (0.3) | 12.7 (1.3)*** |

| Mental illness | 6.2 (0.2) | 7.8 (1.4) | 7.2 (0.3) | 13.9 (1.3)*** |

| Family circumstances | ||||

| Biological parents stopped living together | 15.8 (0.4) | 18.5 (2.3) | 12.1 (0.4) | 18.5 (1.4)*** |

| Traumatic events | ||||

| Victim of violence in the community | 12.0 (0.4) | 21.9 (2.2)*** | 4.8 (0.2) | 14.2 (1.4)*** |

| See someone killed, see a dead body | 12.3 (0.4) | 17.8 (2.2)* | 5.3 (0.2) | 8.4 (1.0)* |

| Economic circumstances | ||||

| Poverty | 12.5 (0.4) | 19.5 (2.0)** | 12.8 (0.4) | 30.0 (1.7)*** |

| Adulthood stressors | ||||

| Financial stressors | ||||

| Financial crisis | 3.1 (0.2) | 8.0 (0.8)*** | 4.2 (0.2) | 12.6 (0.8)*** |

| Fired/laid off | 3.3 (0.2) | 7.6 (1.0)*** | 5.0 (0.2) | 11.1 (1.2)*** |

| Unemployed ≥ 1 month | 3.3 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.8)** | 4.7 (0.2) | 12.1 (1.0)*** |

| Income below 150% of poverty | 16.0 (0.5) | 21.4 (2.4)** | 24.2 (0.6) | 34.3 (1.8)*** |

| Changed job or hours | 3.3 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.4)* | 4.5 (0.2) | 8.4 (0.5)*** |

| Relationship stressors | ||||

| Moved, or someone new moved in | 3.2 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.4)*** | 4.3 (0.2) | 9.2 (0.6)*** |

| new moved in Trouble with boss or coworker | 3.3 (0.2) | 6.7 (0.9)*** | 4.9 (0.2) | 10.5 (0.8)*** |

| Serious problem with neighbor, friend | 3.4 (0.2) | 7.3 (1.2)** | 4.6 (0.2) | 14.8 (1.3)*** |

| Child aged <5 years in house | 3.2 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.7)*** | 4.5 (0.2) | 10.7 (0.7)*** |

| Loved one died | 3.2 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.3)** | 4.7 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.4)*** |

| Loved one other trauma | 3.5 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.2) | 6.8 (0.6)* |

| Crime and violence | ||||

| Something stolen | 3.3 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.8)*** | 4.7 (0.2) | 11.9 (0.9)*** |

| Property destroyed | 3.4 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.8)** | 4.8 (0.2) | 12.4 (1.2)*** |

| Violent victimization in community | 3.5 (0.2) | 7.9 (1.8)* | 5.2 (0.2) | 15.6 (2.5)** |

| See someone killed, see a dead body | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.3 (0.8) | 5.2 (0.2) | 9.6 (1.4)** |

| Other stressors | ||||

| Illness, injury, or disaster | 3.5 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.9) |

| Other trauma to self | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.2 (1.8) | 5.3 (0.2) | 12.0 (3.0)* |

Chi-square test,

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Differences in mean age at interview evaluated with a t-test.

Models of Childhood Adversities and Risk of Perpetration

Physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse were significant predictors of IPV perpetration for both genders in multivariate models including all childhood adversities. For men, witnessing IPV also predicted perpetration. For women, physical neglect, mental illness of a parent, violent victimization in the community, and poverty predicted perpetration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence associated with adverse childhood events, U.S. men and women aged ≥ 20 years (N=34 653)†

| Men (n=14 564) | Women (n=20 089) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Abuse and neglect | ||

| Physical abuse | ||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Some | 1.08 (0.81, 1.44) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.69) |

| Serious | 1.64 (1.11, 2.43)* | 1.77 (1.37, 2.29)*** |

| Witness IPV | ||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Some | 1.47 (1.09, 1.99) | 1.04 (0.82, 1.33) |

| Serious | 1.62 (1.12, 2.34)** | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) |

| Emotional abuse | ||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Some | 1.60 (1.16, 2.21) | 1.62 (1.29, 2.03) |

| Serious | 1.05 (0.63, 1.76)** | 1.10 (0.81, 1.48)*** |

| Sexual abuse | 1.58 (1.13, 2.22)** | 1.32 (1.13, 1.55)*** |

| Physical neglect | ||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Some | 1.11 (0.87, 1.42) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.46) |

| Serious | 1.10 (0.76, 1.57) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.18)* |

| Emotional neglect | ||

| Low | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Medium | 1.04 (0.80, 1.35) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.47) |

| High | 1.17 (0.81, 1.68) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.44) |

| Problems of parent/adult in home | ||

| Mental illness | 0.90 (0.61, 1.34) | 1.27 (1.02, 1.58)* |

| Problem alcohol user | 1.13 (0.85, 1.51) | 0.98 (0.83, 1.17) |

| Problem drug user | 0.82 (0.52, 1.30) | 1.10 (0.87, 1.40) |

| Imprisoned | 1.22 (0.81, 1.84) | 0.94 (0.76, 1.16) |

| Family problems | ||

| Parents divorced or separated | ||

| Not in childhood | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Before age 12 years | 0.74 (0.48, 1.15) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.45) |

| In adolescence | 0.89 (0.64, 1.24) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) |

| Violence exposure | ||

| Victim of violence in the community | ||

| Not in childhood | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Before age 12 years | 1.26 (0.95, 1.67) | 1.56 (1.23, 1.98) |

| In adolescence | 1.23 (0.72, 2.13) | 1.24 (0.78, 1.96)** |

| See someone killed, see a dead body | ||

| Not in childhood | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Before age 12 years | 1.01 (0.74, 1.38) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.35) |

| In adolescence | 1.16 (0.73, 1.83) | 0.79 (0.55, 1.15) |

| Economic circumstances | ||

| Poverty | 1.03 (0.78, 1.34) | 1.37 (1.14, 1.65) |

One multivariable model for each gender, adjusted for age at interview and race/ethnicity

Wald F test for the variable is significant at:

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Models of Adulthood Stressors and Risk of Perpetration

Past–12-month stressors associated with risk of perpetration for both genders included financial crisis, a serious problem with a neighbor or friend, and death of a loved one (adjusted risk ratio (ARR) range: 1.19–1.90) (Table 3). For men but not women, having a young child in the house (ARR=1.46) and being fired (ARR=1.45) were associated with perpetration. For women but not men, being unemployed for more than 1 month (ARR=1.24) and experiencing any other highly stressful event (ARR=1.66) were associated with perpetration. Several stressors, including low income, moving or someone new moving in, and having something stolen, were significantly associated with perpetration among women but among men risk from these stressors was slightly smaller and not significant.

Table 3.

Risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence associated with past–12-month adulthood stressors, U.S. men and women aged ≥ 20 years (N=34 653)†

| Men (n=14 564) | Women (n=20 089) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Financial stressors | ||

| Financial crisis | 1.72 (1.30, 2.28)*** | 1.52 (1.31, 1.77)*** |

| Fired/laid off | 1.45 (1.03, 2.04)* | 0.96 (0.74, 1.25) |

| Unemployed ≥ 1 month | 0.98 (0.67, 1.44) | 1.24 (1.00, 1.52)* |

| Income | ||

| Below 150% of poverty | 1.14 (0.83, 1.56) | 1.33 (1.12, 1.59)*** |

| Below U.S. median | 1.19 (0.95, 1.49) | 1.28 (1.07, 1.52) |

| Above U.S. median | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Changed job or hours | 0.78 (0.62, 0.99)* | 0.89 (0.75, 1.06) |

| Relationship stressors | ||

| Serious problem with neighbor, friend | 1.46 (1.02, 2.07)* | 1.90 (1.56, 2.32)*** |

| Trouble with boss or coworker | 1.35 (1.00, 1.84) | 1.16 (0.96, 1.41) |

| Loved one died | 1.28 (1.04, 1.58)* | 1.19 (1.02, 1.39)* |

| Loved one other trauma | 0.97 (0.71, 1.31) | 1.04 (0.85, 1.28) |

| Child aged <5 years in house | 1.46 (1.10, 1.94)* | 1.15 (0.99, 1.34) |

| Crime and violence | ||

| Something stolen | 1.24 (0.91, 1.60) | 1.31 (1.09, 1.59)** |

| Property destroyed | 1.16 (0.84, 1.60) | 1.26 (0.99, 1.60) |

| Violent victimization in community | 1.43 (0.83, 2.47) | 1.09 (0.68, 1.74) |

| See someone killed, see a dead body | 0.75 (0.43, 1.30) | 1.02 (0.76, 1.38) |

| Other stressors | ||

| Illness, injury, or disaster | 1.09 (0.74, 1.62) | 0.99 (0.74, 1.33) |

| Moved, or someone new moved in | 1.15 (0.93, 1.42) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40)* |

| Self other trauma | 0.70 (0.21, 2.28) | 1.66 (1.07, 2.58)* |

One multivariable model for each gender, adjusted for age at interview and race/ethnicity

Wald F test for the variable is significant at:

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

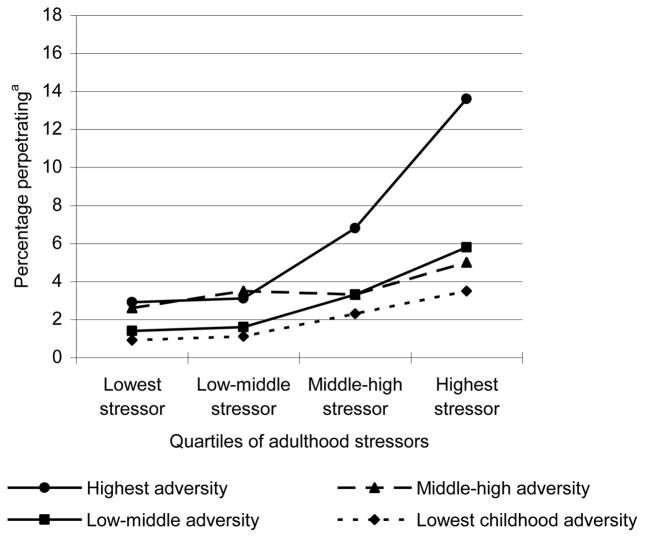

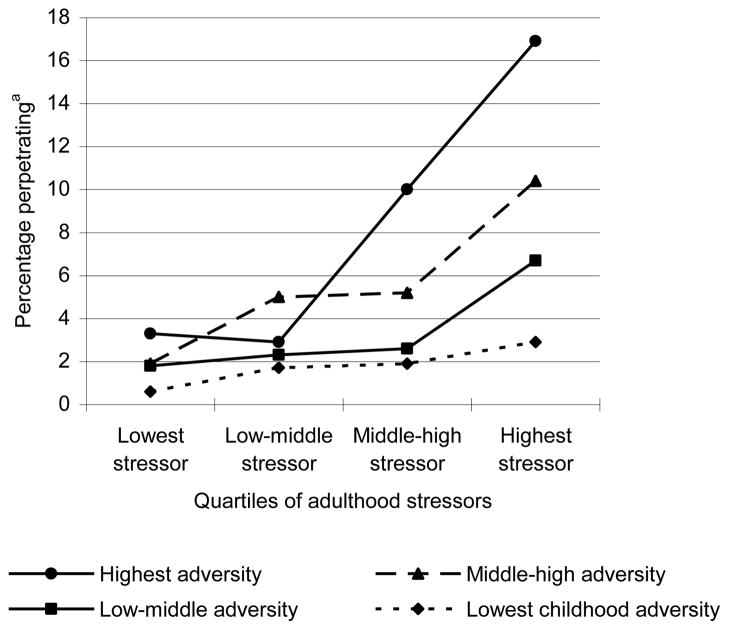

Stress Sensitization Model

Analyses found evidence for stress sensitization effects in predicting IPV for both genders. As hypothesized, the risk of perpetrating IPV among individuals exposed to high levels of past-year stressors as compared to low levels of past-year stressors was significantly greater among respondents with a history of childhood adversity (women, , P<0.001; men, , P<0.001)(Table 4). For men with the least childhood adversity, the risk of perpetrating was 3.5% for men in the highest-stressor quartile and 0.9% for men in the lowest-stressor quartile, for a risk difference of 2.6% (ref). The risk difference between highest and lowest stressor was 5.7% for the low-middle level of childhood adversity (t=−0.02, P=0.1, compared with the referent), 2.4% for the middle-high level (t=1.6, P=0.1), and 10.6% for the highest level (t=4.1, P<0.001) (Figures 1 and 2). Among women, the same pattern was observed: the risk difference was 2.3% for women with the least childhood adversity (ref), 4.8% for low-middle adversity (t=−1.1, P=0.3 compared with the referent), 8.5% for middle-high adversity (t=3.2, P<0.01), and 13.6% for women with high adversity (t=5.5, P<0.001).

Table 4.

Risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence by level of childhood adversity and adulthood stressors, U.S. men and women, aged ≥ 20 years, 2004–2005, N=34653

| Childhood adversity | Adulthood past–12-month stressors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) (n=14 564) | Women (%) (n=20 089) | |||||||

| Lowest stressors | Low-middle stressors | Middle-high stressors | Highest stressors | Lowest stressors | Low-middle stressors | Middle-high stressors | Highest stressors | |

| Lowest adversity | 0.9 (n=1674) | 1.1 (n=1144) | 2.3 (n=741) | 3.5 (n=322) | 0.6 (n=2268) | 1.7 (n=1334) | 1.9 (n=943) | 2.9 (n=464) |

| Low-middle adversity | 1.4 (n=1076) | 1.6 (n=1035) | 3.3 (n=811) | 5.8 (n=561) | 1.8 (n=1349) | 2.3 (n=1401) | 2.6 (n=1394) | 6.7 (n=1015) |

| Middle-high adversity | 2.6 (n=480) | 3.5 (n=785) | 3.3 (n=1052) | 5.0 (n=1237) | 1.9 (n=1003) | 5.0 (n=1353) | 5.2 (n=1327) | 10.4 (n=1234) |

| Highest adversity | 2.9 (n=420) | 3.1 (n=670) | 6.8 (n=1035) | 13.6 (n=1521) | 3.3 (n=402) | 2.9 (n=934) | 10.0 (n=1358) | 16.9 (n=2310) |

Adjusted for race/ethnicity and age at interview

Figure 1.

Prevalence of perpetrating intimate partner violence by level of adulthood stressor and childhood adversity, U.S. 2004–2005, men

aadjusted for race/ethnicity and age

Figure 2.

Prevalence of perpetrating intimate partner violence by level of adulthood stressor and childhood adversity, U.S. 2004–2005, women

aadjusted for race/ethnicity and age

Discussion

Our major finding is that there is an interaction between recent stressors and childhood adversity, such that individuals exposed both to recent stressors and childhood adversity are at greater risk of IPV perpetration than would be predicted by an additive effect of stressors and childhood adversity alone. Prior work has examined the effects of childhood adversity and recent adult stressors separately and found that both predict perpetration. However, the current results show that association of recent stressors and IPV perpetration is strongest among individuals with high levels of childhood adversity, which has not been previously demonstrated. The current findings extend the stress sensitization literature from mood and anxiety disorders23, 24, 26, 49 into the realm of externalizing behaviors, suggesting a broad effect of childhood stress sensitization on adult mental health and behaviors.

The stress sensitization effect found was most pronounced at high levels of stressors, that is, the risk difference for the highest-level childhood adversity group versus the lower-level groups was largest among people experiencing the most adult stressors. In prior research, stress sensitization has been investigated in three distinct manifestations. First, studies have found that exposure to childhood adversities lowers the stress threshold at which negative sequelae, such as depression24 or bipolar episodes49 occur, such that minor stressors trigger these events. Second, stress sensitization has been investigated with regard to increasing the severity of mental illness sequelae.23 Finally, stress sensitization has been found to increase likelihood of mental illness following exposure to major stressors.26 The current findings support this third conceptualization. It was not found that small differences in stressors were associated with greater risk for IPV perpetration among individuals with childhood adversity.

The stress sensitization hypothesis was supported for both men and women. These findings concur with a growing body of research showing commonalities across genders in IPV perpetration in high-income countries.50–55 Overall, there were striking similarities in the adjusted models for both genders in terms of which childhood events were risk factors for perpetration, which adulthood stressors were associated with perpetration, and the magnitude of these associations. The current finding that the prevalence of IPV perpetration, including serious perpetration, was somewhat higher in women than men is consistent with prior work,8, 9, 12, 56–59 as is the current finding that women are victimized by the most-severe acts more often than men.1, 60 These studies are limited to high-income countries, however, and therefore findings may not hold for countries in which women’s status is substantially lower than men’s or in which violence against women is condoned.

Our findings are subject to four main limitations. First, childhood experiences and IPV perpetration were retrospectively self-reported. Retrospective-61 and self-reporting9, 38 can lead to under-reporting, which could attenuate relationships between adversities or stressors and perpetration. In contrast, social desirability bias could cause overestimation of the adversity–IPV association if both adversity and IPV are under-reported. Second, recall bias may lead to overestimation of the association between stressors, adversities and perpetration, if perpetrators better recall these negative events. Third, the chronology of past-year perpetration and stressors was not established, although stressors that could logically result from perpetration were excluded. Fourth, other factors, such as poor social functioning,15, 17 aggressiveness,18 or personality disorders18, 62 may be common causes of both stressors and perpetration.

The role of stress sensitization in IPV perpetration has implications for theory, research, and practice. The current findings highlight the importance of a life course perspective on IPV perpetration. Existing studies primarily focus on either childhood or adulthood predictors, and rarely examine sets of factors across life stages. Research examining both childhood and adulthood risk factors has viewed adulthood factors, such as mental illness,11, 62, 63 substance use,11, 64 and community violence65 primarily as mediators of childhood adversity. Thus, when examined in conjunction with childhood circumstances, adulthood circumstances have been considered mainly as consequences of the childhood environment. The current results suggest that considering adulthood circumstances as precipitators of perpetration in the context of childhood adversity represents a fruitful area of study.66, 67

Our findings further suggest that research on IPV perpetration may benefit from examining neural, physiologic, and neuroendocrine response to stressors in IPV perpetrators compared with nonperpetrators to identify biological mechanisms. Prior work examining reactivity in perpetrators has focused on differences in cardiovascular reactivity among types of perpetrators, with contradictory findings.68, 69 Other pathways involved in stress response have not been explored. For example, the orbitofrontal cortex may regulate aggression in response to threat or frustration; such aggression can be triggered more readily if the regulatory systems involved in this response are damaged from prior trauma.70, 71 The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, the neurotransmitters serotonin, γ-amino butyric acid (GABA), and dopamine, and functionality of these neurotransmitters’ receptors have also been implicated in aggression70, 72 and dysregulation of these systems has been associated with stress reactivity from childhood adversity.73–75

In terms of practice, the current results indicate that intervention programs may want to explore more extensively the role of stress and reaction to stress in perpetration, particularly among individuals with histories of childhood maltreatment. Existing treatments for IPV perpetrators, primarily the Duluth model and cognitive–behavioral therapy, are no more effective than arrest alone in preventing subsequent perpetration.76–79 Stress management training,80 mindfulness training,81–83 and psychotherapy84 reduce reactivity to stress, and therefore may be useful in treating perpetrators.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrea Roberts is supported by the Harvard Training Program in Psychiatric Genetics and Translational Research (grant T32MH017119). Dr. Katie McLaughlin is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 053572). Dr. Kerith Conron is supported by the Institute on Urban Health Research and CSAT (grants TI19574 and TI18880). Dr. Karestan Koenen is supported by NIH (grants MH078928, DA022720, and MH086309), the Kaiser Family Foundation, and a Junior Faculty Sabbatical from Harvard School of Public Health.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(7):538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker MW, LaCroix AZ, Wu CY, Cochrane BB, Wallace R, Woods NF. Mortality Risk Associated with Physical and Verbal Abuse in Women Aged 50 to 79. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2009;57(10):1799–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coker AL, Watkins KW, Smith PH, Brandt HM. Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: application of structural equation models. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher J. The effects of intimate partner violence on health in young adulthood in the U. S Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid RJ, Bonomi AE, Rivara FP, et al. Intimate partner violence among men—Prevalence, chronicity, and health effects. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Developmental antecedents of interpartner violence in a New Zealand birth cohort. J Fam Violence. 2008;23(8):737–753. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Molnar BE, Feurer ID, Appelbaum M. Patterns and mental health predictors of domestic violence in the U.S: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2001;24(4–5):487–508. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(01)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinney CM, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Nelson S. Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence: findings from a national population-based study of couples. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White HR, Widom CS. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility and alcohol problems. Aggress Behav. 2003;29(4):332–345. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delsol C, Margolin G. The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(1):99–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62(3):640–654. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250(4988):1678–83. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2003;39(2):349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fite JE, Bates JE, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Dodge KA, Nay SY, Pettit GS. Social information processing mediates the intergenerational transmission of aggressiveness in romantic relationships. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(3):367–76. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: men’s and women’s participation and developmental antecedents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(2):258–70. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essex MJ, Klein MH, Cho E, Kalin NH. Maternal stress beginning in infancy may sensitize children to later stress exposure: effects on cortisol and behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(8):776–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oosterman M, De Schipper JC, Fisher P, Dozier M, Schuengel C. Autonomic reactivity in relation to attachment and early adversity among foster children. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(1):109–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 34(6):867–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Stress sensitization and adolescent depressive severity as a function of childhood adversity: a link to anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(2):287–99. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammen C, Henry R, Daley SE. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):782–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1475–82. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med. 2009:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser JP, van Os J, Portegijs PJ, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wichers M, Geschwind N, Jacobs N, et al. Transition from stress sensitivity to a depressive state: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):498–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cano A, Vivian D. Life stressors and husband-to-wife violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2001;6(5):459–480. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cano A, Vivian D. Are life stressors associated with marital violence? J Fam Psychol. 2003;17(3):302–314. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer A, Lawrence E, Barry RA. Using a Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Framework to Predict Physical Aggression Trajectories in Newlywed Marriage. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(5):756–768. doi: 10.1037/a0013254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frye NE, Karney BR. The context of aggressive behavior in marriage: A longitudinal study of newlyweds. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(1):12–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seltzer JA, Kalmuss D. Socialization and stress explanations for spouse abuse. Social Forces. 1988;67(2):473. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straus MA. Social stress and marital violence. In: Straus MA, editor. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1990. pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant B, Kaplan K. Source and accuracy statement for the wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1–3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Straus M, Gelles R. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick: Transaction Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Krueger RF, et al. Do partners agree about abuse in their relationship? A psychometric evaluation of interpartner agreement. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1990. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22(4):249–70. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–90. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9(4):507–19. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among U.S. sexual orientation minority adults and posttraumatic stress disorder risk. Am J Public Health. 2010;(6) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the U.S. Psychol Med. :1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Walker AM. Concepts of interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(4):467–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Hoewyk JV. IVEware: Imputation and variance estimation software survey methodology program. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Hoewyk JV, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, Cohen AN, Daley SE. The stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;95(1–3):43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medeiros RA, Straus MA. Risk factors for physical violence between dating partners: Implications for gender-inclusive prevention and treatment of family violence. In: Hamel J, Nicholls T, editors. Family approaches in domestic violence: A practitioner’s guide to gender-inclusive research and treatment. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stets JE, Straus MA. Gender differences in reporting marital violence and its medical and psychological consequences. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1990. pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kernsmith P. Gender differences in the impact of family of origin violence on perpetrators of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21(2):163–171. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sommer R. Male and female perpetrated partner abuse: Testing a stress-diathesis model. Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stets JE, Straus MA. The marriage license as a hitting license: A comparison of assaults in dating, cohabitating, and married couples. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1990. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: a prospective-longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):375–89. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brush LD. Violent Acts and Injurious Outcomes in Married Couples: Methodological Issues in the National Survey of Families and Households. Gender Soc. 1990;4(1):56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Renner LM, Whitney SD. Examining Symmetry in Intimate Partner Violence Among Young Adults Using Socio-Demographic Characteristics. J Fam Violence. 2010;25(2):91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lussier P, Farrington DP, Moffitt TE. Is the antisocial child father of the abusive man? A 40-year prospective longitudinal study on the developmental antecedents of intimate partner violence. Criminology. 2009;47(3):741–780. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(5):651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Johnson JG. Development of Personality Disorder Symptoms and the Risk for Partner Violence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):474–483. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taft CT, Schumm JA, Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Family-of-origin maltreatment, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, social information processing deficits, and relationship abuse perpetration. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(3):637–46. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fuller BE, Chermack ST, Cruise KA, Kirsch E, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Predictors of aggression across three generations among sons of alcoholics: relationships involving grandparental and parental alcoholism, child aggression, marital aggression and parenting practices. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(4):472–83. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Mason WA, Hawkins JD. Youth violence trajectories and proximal characteristics of intimate partner violence. Violence Vict. 2007;22(3):259–74. doi: 10.1891/088667007780842793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aldarondo E, Sugarman DB. Risk marker analysis of the cessation and persistence of wife assault. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(5):1010–1019. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Babcock JC, Costa DM, Green CE, Eckhardt CI. What situations induce intimate partner violence? A reliability and validity study of the Proximal Antecedents to Violent Episodes (PAVE) scale. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(3):433–42. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babcock JC, Green CE, Webb SA, Graham KH. A second failure to replicate the Gottman et al. (1995) typology of men who abuse intimate partners… and possible reasons why. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(2):396–400. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gottman JM, Jacobson NS, Rushe RH, et al. The relationship between heart rate reactivity, emotionally aggressive behavior, and general violence in batterers. J Fam Psychol. 1995:227–248. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blair RJR, Charney DS. Emotion regulation: An affective neuroscience approach. In: Mattson MP, editor. Neurobiology of aggression: Understanding and preventing violence. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2003. pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shea A, Walsh C, Macmillan H, Steiner M. Child maltreatment and HPA axis dysregulation: relationship to major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(2):162–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lesch KP. The Serotonergic Dimension of Aggression and Violence. In: Mattson MP, editor. Neurobiology of aggression: Understanding and preventing violence. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2003. pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Glaser D. Child Abuse and Neglect and the Brain—A Review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haller J, Kruk MR. Neuroendocrine Stress Responses and Aggression. In: Mattson MP, editor. Neurobiology of aggression: Understanding and preventing violence. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2003. pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacMillan HL, Georgiades K, Duku EK, et al. Cortisol response to stress in female youths exposed to childhood maltreatment: results of the youth mood project. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23(8):1023–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stover CS, Meadows AL, Kaufman J. Interventions for Intimate Partner Violence: Review and Implications for Evidence-Based Practice. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 2009;40(3):223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feder L, Dugan L. A test of the efficacy of court-mandated counseling for domestic violence offenders: The broward experiment. Justice Q. 2002;19(2):343–375. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Feder L, Wilson DB. A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: Can courts affect abusers’ behavior? J Experimental Criminology. 2005;1(2):239–262. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vocks S, Ockenfels M, Jurgensen R, Mussgay L, Ruddel H. Blood pressure reactivity can be reduced by a cognitive behavioral stress management program. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11(2):63–70. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(1):11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, et al. Mindfulness training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: results from a randomized, controlled stage I pilot study. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):306–17. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davis JM, Fleming MF, Bonus KA, Baker TB. A pilot study on mindfulness-based stress reduction for smokers. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hawley LL, Ringo Ho MH, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. Stress reactivity following brief treatment for depression: differential effects of psychotherapy and medication. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(2):244–56. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]