Abstract

Recent studies have proposed an interrelation between the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) val66met polymorphism and the serotonin system. In this study, we investigated whether the BDNF val66met polymorphism or blood BDNF levels are associated with cerebral 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) receptor or serotonin transporter (SERT) binding in healthy subjects. No statistically significant differences in 5-HT2A receptor or SERT binding were found between the val/val and met carriers, nor were blood BDNF values associated with SERT binding or 5-HT2A receptor binding. In conclusion, val66met BDNF polymorphism status is not associated with changes in the serotonergic system. Moreover, BDNF levels in blood do not correlate with either 5-HT2A or SERT binding.

Keywords: BDNF, 5-HT2A, imaging, polymorphism, SERT, val66met

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) belongs to the family of neurotrophins and is primarily produced in neurons and glia cells and to a lesser extent in endothelial cells (Leventhal et al, 1999), leucocytes (Kerschensteiner et al, 1999), and satellite cells in skeletal muscles (Mousavi and Jasmin, 2006). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is important for growth of the central nervous system during fetal development, whereas in adults, BDNF is primarily involved in synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuronal survival (for review, see Waterhouse and Xu, 2009). Moreover, BDNF also affects synthesis and release of several neurotransmitters, including serotonin (Messaoudi et al, 1998).

Several studies point toward an involvement of BDNF in neuropsychiatric and neurologic disorders, such as depression and Alzheimer's disease (Connor et al, 1997; Karege et al, 2005). For example, serum BDNF levels are lower in patients with depression (Brunoni et al, 2008) and in women, genetically predisposed to depression and exposed to recent stressful life events (Trajkovska et al, 2008). In a recent meta-analysis study, it was shown that serum BDNF levels increased after antidepressant treatment (Brunoni et al, 2008).

Another method to investigate effects of perturbed BDNF signaling on the serotonin system is to study individuals carrying polymorphisms in the BDNF gene, e.g., the val66met polymorphism. This single-nucleotide polymorphism in the 5′-prodomain region of the BDNF gene leads to a nucleotide change in codon 66, where the amino acid valine (val) is substituted by methionine (met) in the propart of the BDNF protein (Egan et al, 2003). The propart is later cleaved off by proteases, such that the val66met substitution is not transferred to the mature form of BDNF. The presence of the met allele leads to a disturbance in the activity-dependent BDNF secretion (controlled by neuronal activity), while the constitutive secretion remains unaffected (Egan et al, 2003). The val66met polymorphism is relatively frequent in Caucasians (19–25%) and in Asians (45%) (Shimizu et al, 2004; Hwang et al, 2006). In vivo neuroimaging studies have shown that in healthy subjects, the met allele is associated with lower volumes of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and poorer performance in episodic memory tests (Hariri et al, 2003; Egan et al, 2003; Pezawas et al, 2004).

A close interaction between BDNF and the serotonergic system has previously been described (for review, see Mattson et al, 2004). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor provides neurotrophic support for serotonergic neurons and changes in BDNF levels affect the function of serotonin transporter (SERT) (Guiard et al, 2008), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A (Hensler et al, 2007), and 5-HT2A receptors (Rios et al, 2006). Functional studies of SERT function in heterozygous BDNF knockout mice showed a decreased rate of serotonin uptake in the ventral hippocampus (Daws et al, 2007; Guiard et al, 2008). In line with this, a positron emission tomography (PET) study of 25 healthy individuals showed that the val/val genotype was associated with increased SERT binding in men (Henningsson et al, 2009). In addition, a val66met interaction with the 5-HTTLPR (5-HT-transporter-linked promoter region) polymorphism in relation to neuroticism (a risk factor for developing major depression) has been reported (Terracciano et al, 2010).

Interactions with BDNF have also been reported for the 5-HT2A receptor. For example, conditional BDNF knockout mice have severe impairment of cortical 5-HT2A receptor function and decreased protein levels of the receptor in the frontal cortex (Rios et al, 2006). Furthermore, recent studies from our group showed that frontolimbic 5-HT2A receptor binding was positively correlated with neuroticism score and that this association was particularly strong in individuals with high familial risk for developing depression (Frokjaer et al, 2008, 2010). These studies are suggestive of an interaction between BDNF and frontal cortex 5-HT2A receptors, a claim which has been further substantiated by the finding of a direct regulatory effect of BDNF on the density of 5-HT2A receptors in vitro (Trajkovska et al, 2009).

In this study, we investigated a large cohort of healthy individuals to determine whether the met allele of the BDNF val66met polymorphism or whole-blood levels of BDNF are associated with cerebral 5-HT2A receptor binding measured by [18F]altanserin PET and subcortical SERT binding measured by [11C]DASB PET. On the basis of available experimental and clinical data, we hypothesized that the presence of the met allele would result in lower cortical 5-HT2A binding and lower subcortical SERT binding. Finally, we expected a positive correlation between BDNF whole-blood levels and neocortical 5-HT2A receptor and subcortical SERT binding.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 133 individuals (88 men, median age 34 years, range, 18–81 years) were recruited from newspaper announcements and were included in the study after medical screening. The absence of psychiatric and neurologic disorders was ensured by obtaining a detailed interview, and by clinical evaluation. Subsets of the sample were included in previous publications (Frokjaer et al, 2008, 2009; Erritzoe et al, 2009).

Imaging

All subjects were PET scanned using an 18-ring GE-Advance scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) in a three-dimensional acquisition mode, producing 35 image slices with an interslice distance of 4.25 mm. [18F]altanserin was injected into the cubital vein as a combination of a bolus and a continuous infusion (ratio 1.75 hours) to obtain tracer steady state in blood and tissue according to Pinborg et al (2003). A maximal dose of [18F]altanserin of 3.7 MBq/kg bodyweight, was administered with an average dose of 270 MBq. Dynamic three-dimensional emission scans (5 frames of 8 minutes each) started 120 minutes after administration of [18F]altanserin. Blood samples were collected at mid-PET frame times and analyzed with high-performance liquid chromatography for determination of the activity of the nonmetabolized tracer in the plasma. Visual inspection of the time–activity curves was performed to ensure constant blood and tissue levels. The plasma metabolites of [18F]altanserin were determined using a modification of previously published procedures (Pinborg et al, 2003).

For [11C]DASB, a dynamic 90-minute-long emission recording was initiated during intravenous injection during 12 seconds of 485±86 MBq (range, 279–601 MBq) [11C]DASB, with specific activity of 29±16 GBq/μmol (range, 9–82 GBq/μmol).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on all subjects; magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequences were acquired on either a 1.5-T Vision scanner (N=69) or a 3-T Trio scanner (N=64) (both from Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

Image Analysis

The MRI images were coregistered with the PET images using a Matlab-based (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) interactive program, which is based on visual identification of the transformation as described in the study by Adams et al (2004). The MRIs were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid tissue classes using SPM2 (Welcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College London, London, UK). A total of 35 regions of interest were automatically delineated on MRI slices (Svarer et al, 2005) and transferred to PET images using the identified rigid body transformation. These PET images were partial volume corrected by means of the segmented MRI. A three-compartment model based on gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid tissue was used (Quarantelli et al, 2004). The white matter value was extracted as the average voxel value from a white matter region of interest (midbrain) in the uncorrected PET image.

The volume of distribution (Vd) and binding potential (BPp) for [18F]altanserin and [11C]DASB were calculated as described in the studies by Pinborg et al (2003) and Frokjaer et al (2009), respectively.

A volume-weighted mean of cortical 5-HT2A binding was subsequently calculated and used as a measure of average brain cortical binding because we primarily tested the hypothesis that the association between the val66met polymorphism and in vivo 5-HT2A would be reflected as a global effect on receptor density. The mean neocortical binding was calculated from the volume-corrected binding in the following areas: the orbitofrontal cortex, medial inferior frontal cortex, anterior cingulate, insular cortex, superior temporal cortex, parietal cortex, medial inferior temporal cortex, superior frontal cortex, occipital cortex, sensory and motor cortices, and posterior cingulate cortex. Values from left and right sides were averaged. A mean value for [11C]DASB binding was calculated from a subcortical high-binding region consisting of a volume-weighted average of the caudate, putamen, and thalamus.

Assessment of Neuroticism Score

On the same day as the PET scanning, subjects completed the Danish version of the 240-item NEOPI-R (Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Personality Inventory Revised) self-report personality questionnaire as described previously (Costa and McCrae, 1992; Frokjaer et al, 2008). The neuroticism score is calculated as the sum of the score in each of the six subdimensions (facets) comprised in this personality trait.

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Genotyping

Blood samples for DNA analysis and BDNF measurements were collected at the day of the PET scanning and immediately frozen and stored at −20°C until further analysis. DNA was extracted from the blood with a Qiagen Mini kit using the guidelines included in the kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met genotyping was performed using a TaqMan 5′-exonuclease allelic discrimination assay according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA, Assay-on-Demand single-nucleotide polymorphism product: C_11592758_10). The ABI 7500 multiplex PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) was used for this analysis.

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Measurements

To measure the blood BDNF concentration, blood samples were obtained at the day of the PET scanning session and 1.5 mL of whole blood was sampled in EDTA-containing tubes and immediately frozen at −20°C. On the day of analysis, blood samples were thawed on ice and 3% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich, Copenhagen, Denmark) were added to the samples. Samples were then sonicated and centrifuged (12,000 × g) for 10 minutes and 0.5 mL of the supernatant was aliquoted in new tubes. The following measurement of BDNF content in the lysated blood using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was conducted as described previously (Trajkovska et al, 2007).

Statistical Analysis

A genotype equilibrium test was performed using Pearson's χ2 test. Correlation analyses between whole-blood BDNF and binding were performed using multiple regression analysis, including the covariates, age, neuroticism, body mass index, as well as free fraction of the radiotracer for [18F]altanserin and gender, age, daylight minutes, and openness for [11C]DASB data. Comparisons between val/val and met carriers were made using Student's t-test. Grubbs' outlier test was used for detecting outliers (an outlier was detected for BPp in the met+ group, mean: 3.7; Z-value: 3.9, P<0.05, and therefore not included in the following BPp-val66met analysis). Unless otherwise stated, the values are presented as mean±s.d. The level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

The genotype distributions for subjects scanned with [18F]altanserin and [11C]DASB study are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The val/val and met frequencies were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and correspond to those previously reported for Caucasians (Egan et al, 2003).

Table 1. Data on healthy subjects PET scanned with [18F]altanserin.

| PET-[18F]altanserin (n=133) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| val/val | met+ | Student's t-test | |

| n | 90 | 43 (6) | |

| Age (years) | 40±19 | 41±18 | P=0.86 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.6±3.3 | 24.7±3.0 | P=0.95 |

| Neuroticism | 72±18 | 69±19 | P=0.44 |

BMI, body mass index; PET, positron emission tomography; 5-HT2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A.

val66met allele distribution in scanned healthy subjects. Allele distribution was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (Pearson χ2 test). Age, BMI, and neuroticism have been shown to affect cortical 5-HT2A binding, but no differences were found between val/val and met carriers (Student's t-test). The number in brackets in met+ indicates the number of met/met subjects. Values represent mean±s.d.

Table 2. Data on healthy subjects PET scanned with [11C]DASB.

| PET-[11C]DASB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=49) | Males | Females | ||||

| val/val | met+ | Student's t-test | val/val | met+ | Student's t-test | |

| n | 27 | 6 (1) | 11 | 5 (2) | ||

| Age (years) | 34±19 | 32±18 | P=0.78 | 43±21 | 40±23 | P=0.85 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9±2.5 | 25.9±3.2 | P=0.09 | 24.5±3.4 | 27.3±3.3 | P=0.15 |

| Daylight minutes | 746±246 | 798±281 | P=0.65 | 725±200 | 635±174 | P=0.41 |

| Openness | 117±19 | 112±12 | P=0.53 | 122±18 | 125±16 | P=0.80 |

BMI, body mass index; PET, positron emission tomography; 5-HT2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A.

A total of 49 subjects scanned with 18F-altanserin were also scanned with 11C-DASB. Here, possible confounders are age, BMI, daylight minutes, and openness, but no intergroup differences were found between val/val and met carriers (Student's t-test). The number in brackets in met+ indicates the number of met/met subjects. Values represent mean±s.d.

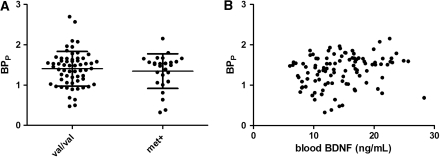

No differences were found in neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding between the val/val and met carrier groups (1.41±0.43 versus 1.35±0.43, respectively, P=0.56) (Figure 1A). There was a tendency toward a positive correlation between BDNF blood levels and neocortical 5-HT2A receptor BPP, but this was no longer evident after adjustment for age and body mass index in a multiple regression analysis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Neocortical 5-HT2A binding in the val/val and met groups. (A) There were no significant differences between the two groups (mean: 1.41±0.43 versus 1.35±0.43). (B) Correlation between BDNF levels in blood and neocortical 5-HT2A binding. Although there was a modest significant positive correlation (P=0.03), this was no longer present after adjustments for age and BMI. BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMI, body mass index; 5-HT2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A.

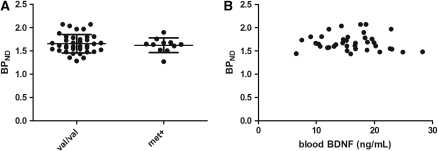

No differences in mean subcortical SERT binding were found between val/val and met carriers (1.66±0.20 versus 1.62±0.16, respectively, P=0.61) (Figure 2A). For SERT binding, we further divided our val/val and met carriers groups in a gender-specific manner. This stratification did not reveal any effects of val66met on SERT binding in either men (1.67±0.21 versus 1.65±0.14, P=0.82) or women (1.62±0.17 versus 1.59±0.19, P=0.74). Moreover, we looked for an association between BDNF levels in blood and SERT binding in the investigated subcortical high-binding region, but no significant correlations were observed (r=−0.09, P=0.59) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Mean SERT binding in the subcortical high-binding region in val/val and met carriers. (A) There were no significant differences in SERT binding between val/val and met carriers (1.66±0.20 versus 1.62±0.16, respectively, P=0.61). (B) Correlations between blood BDNF levels and SERT binding. There were no significant associations between these parameters (r=−0.09, P=0.59). BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; SERT, serotonin transporter.

We controlled for differences between groups regarding age (Adams et al, 2004), body mass index (Erritzoe et al, 2009), and neuroticism (Frokjaer et al, 2008), both of which factors have earlier been shown to correlate with cerebral 5-HT2A binding, but the val66met status was not associated with any of these (Table 1). In addition, there was no correlation between total BDNF levels in blood and the neuroticism score (r=0.05, P=0.63), nor was there any genotype-associated differences in the free fraction of the parent radiotracer, fp (0.47±0.42 versus 0.40±0.17, respectively, P=0.13). The distribution of genotype groups scanned with either the 1.5 T or the 3 T was comparable (46 (1.5 T) versus 44 (3 T) for val/val and 23 (1.5 T) and 30 (3 T) for met carriers), excluding possible confounding effects related to differences in the MR scanner type.

To exclude possible confounders affecting SERT binding in the subcortical high-binding region (such as the caudate, putamen, and thalamus), we controlled for differences between groups regarding daylight minutes and openness, which was recently shown to be associated with SERT binding (Kalbitzer et al, 2009, 2010). No genotype-associated differences were found for these parameters (Table 2). All [11C]DASB scanned subjects for SERT were MR scanned using the 3-T Trio MR scanner type.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effect of val66met on 5-HT2A binding. This is the first study examining the associations in healthy individuals between the val66met BDNF polymorphism carrier status, BDNF levels, and cerebral 5-HT2A receptor and SERT binding. In contrast to our hypothesis, we could not observe any statistically significant association between any of these variables.

The close interaction between BDNF and the 5-HT2A receptor is illustrated by a pronounced effect on the cortical 5-HT2A receptor levels in conditional BDNF knockout mice during embryonic development and the first postnatal weeks (Chan et al, 2006; Rios et al, 2006). Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown a direct regulatory effect of BDNF on 5-HT2A receptor levels (Trajkovska et al, 2009). In this study, we report that there is no interaction between val66met status and neocortical 5-HT2A binding, indicating that the receptor regulations seen in animal studies are independent of activity-induced BDNF secretion, but may depend on total BDNF levels. To investigate this further, we examined the association between BDNF levels in blood and neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding. We found a tendency toward a positive correlation showing the association of low BDNF → low cortical 5-HT2A as observed in animal studies (Rios et al, 2006). However, after adjusting the 5-HT2A binding for age, neuroticism, and body mass index, this tendency was no longer evident, which illustrates the impact of covariates on measured parameters, in this case the neocortical 5-HT2A binding.

One other study has investigated cerebral 5-HT1A receptor and SERT binding and the BDNF val66met polymorphism in 53 and 25 healthy individuals, respectively (Henningsson et al, 2009). They found that whereas BDNF genotypes did not affect 5-HT1A receptor binding in the entire population, male val/val carriers (N=16) had higher cerebral SERT binding than did met carriers. In our study of a two-fold larger group of males (N=33, 11C-DASB-PET), we did not see the gender-dependent allelic differences. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear, which is why additional studies on the val66met–SERT association are required.

We did not see any association between serum BDNF levels and SERT binding, although experimental studies have shown an interaction between BDNF and SERT. However, a decrease in SERT efficiency in heterozygous BDNF knockout mice without concomitant changes in SERT binding has been reported (Daws et al, 2007). This may suggest a role of BDNF levels and val66met on SERT function rather than SERT expression. Alternatively, the BDNF–SERT interaction may be different if BDNF levels are decreased, e.g., during extended periods of major depression (Brunoni et al, 2008). Indeed, an investigation of SERT and val66met interaction in patients with major depression could be an interesting area of future research.

Decreased BDNF levels have also been associated with high neuroticism score in healthy subjects (Lang et al, 2004). We were unable to replicate this finding in our study. One explanation for this discrepancy could be that Lang et al (2004) measured BDNF in serum samples, whereas we measured BDNF in whole blood. However, we have previously shown that serum and whole-blood BDNF values correlate if storage time of the serum samples is <12 months, and that BDNF in whole blood is better preserved during storage (Trajkovska et al, 2007). Moreover, the carrier status of the BDNF val66met polymorphism in our cohort was not associated with the neuroticism score. This result is in accordance with results from a large meta-analysis (Terracciano et al, 2010) and suggests that changes in activity-dependent BDNF secretion in the brain is not linked to risk factors for developing depression per se, but rather to the ability of coping with external effectors, such as stressful life events. For example, in mice carrying the met allele of the val66met polymorphism, there were no changes in baseline stress levels, but the mice were severely affected when exposed to chronic social defeat (Krishnan et al, 2007). Similarly, in a study including human subjects, there was no detected interaction between val66met and early life stress predicted brain and arousal pathways related to depression and anxiety response (Gatt et al, 2009). Unfortunately, in our cohort, we did not have access to this information, but in a previous study we showed a correlation between recent stressful life events and BDNF blood levels in individuals at high familial risk for depression (Trajkovska et al, 2008). Taken together, these studies suggest that the val66met polymorphism primarily gets manifested during processes that require an increase in BDNF secretion. Therefore, it could be speculated that other factors, such as stressful life events, should be taken into consideration when assessing effects of the val66met polymorphism.

In conclusion, we did not find evidence for an interaction between the val66met polymorphism in the BDNF gene, 5-HT2A receptor binding, and SERT binding in healthy subjects or between total BDNF levels and 5-HT2A receptor binding, even when gender-specific analyses were included. We suggest that the val66met polymorphism has a minor impact on the serotonin system in healthy subjects, but has a more significant role when the brain is exposed to stress or when val66met is present together with other polymorphisms in SERT or in serotonin receptors.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams KH, Pinborg LH, Svarer C, Hasselbalch SG, Holm S, Haugbol S, Madsen K, Frokjaer V, Martiny L, Paulson OB, Knudsen GM. A database of [(18)F]-altanserin binding to 5-HT(2A) receptors in normal volunteers: normative data and relationship to physiological and demographic variables. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1105–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni AR, Lopes M, Fregni F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:1169–1180. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JP, Unger TJ, Byrnes J, Rios M. Examination of behavioral deficits triggered by targeting Bdnf in fetal or postnatal brains of mice. Neuroscience. 2006;142:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor B, Young D, Yan Q, Faull RL, Synek B, Dragunow M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;49:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR.1992Revised NEO Personality Inventory an NEO Five Factor Inventory, Professional ManualPsychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL

- Daws LC, Munn JL, Valdez MF, Frosto-Burke T, Hensler JG. Serotonin transporter function, but not expression, is dependent on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF): in vivo studies in BDNF-deficient mice. J Neurochem. 2007;101:641–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, Lu B, Weinberger DR. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112:257–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erritzoe D, Frokjaer VG, Haugbol S, Marner L, Svarer C, Holst K, Baare WF, Rasmussen PM, Madsen J, Paulson OB, Knudsen GM. Brain serotonin 2A receptor binding: relations to body mass index, tobacco and alcohol use. Neuroimage. 2009;46:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer VG, Mortensen EL, Nielsen FA, Haugbol S, Pinborg LH, Adams KH, Svarer C, Hasselbalch SG, Holm S, Paulson OB, Knudsen GM. Frontolimbic serotonin 2A receptor binding in healthy subjects is associated with personality risk factors for affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer VG, Vinberg M, Erritzoe D, Baare W, Holst KK, Mortensen EL, Arfan H, Madsen J, Jernigan TL, Kessing LV, Knudsen GM. Familial risk for mood disorder and the personality risk factor, neuroticism, interact in their association with frontolimbic serotonin 2A receptor binding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1129–1137. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer VG, Vinberg M, Erritzoe D, Svarer C, Baare W, Budtz-Joergensen E, Madsen K, Madsen J, Kessing LV, Knudsen GM. High familial risk for mood disorder is associated with low dorsolateral prefrontal cortex serotonin transporter binding. Neuroimage. 2009;46:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatt JM, Nemeroff CB, Dobson-Stone C, Paul RH, Bryant RA, Schofield PR, Gordon E, Kemp AH, Williams LM. Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:681–695. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard BP, David DJ, Deltheil T, Chenu F, Le ME, Renoir T, Leroux-Nicollet I, Sokoloff P, Lanfumey L, Hamon M, Andrews AM, Hen R, Gardier AM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-deficient mice exhibit a hippocampal hyperserotonergic phenotype. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:79–92. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Mattay VS, Kolachana BS, Callicott JH, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism affects human memory-related hippocampal activity and predicts memory performance. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6690–6694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningsson S, Borg J, Lundberg J, Bah J, Lindstrom M, Ryding E, Jovanovic H, Saijo T, Inoue M, Rosen I, Traskman-Bendz L, Farde L, Eriksson E. Genetic variation in brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with serotonin transporter but not serotonin-1A receptor availability in men. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensler JG, Advani T, Monteggia LM. Regulation of serotonin-1A receptor function in inducible brain-derived neurotrophic factor knockout mice after administration of corticosterone. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JP, Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Yang CH, Lirng JF, Yang YM. The Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic-factor gene is associated with geriatric depression. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1834–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbitzer J, Erritzoe D, Holst KK, Nielsen FA, Marner L, Lehel S, Arentzen T, Jernigan TL, Knudsen GM. Seasonal changes in brain serotonin transporter binding in short serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region-allele carriers but not in long-allele homozygotes. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbitzer J, Frokjaer VG, Erritzoe D, Svarer C, Cumming P, Nielsen FA, Hashemi SH, Baare WF, Madsen J, Hasselbalch SG, Kringelbach ML, Mortensen EL, Knudsen GM. The personality trait openness is related to cerebral 5-HTT levels. Neuroimage. 2009;45:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F, Bondolfi G, Gervasoni N, Schwald M, Aubry JM, Bertschy G. Low brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in serum of depressed patients probably results from lowered platelet BDNF release unrelated to platelet reactivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1068–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschensteiner M, Gallmeier E, Behrens L, Leal VV, Misgeld T, Klinkert WE, Kolbeck R, Hoppe E, Oropeza-Wekerle RL, Bartke I, Stadelmann C, Lassmann H, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R. Activated human T cells, B cells, and monocytes produce brain-derived neurotrophic factor in vitro and in inflammatory brain lesions: a neuroprotective role of inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;189:865–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Graham A, Lutter M, Lagace DC, Ghose S, Reister R, Tannous P, Green TA, Neve RL, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Eisch AJ, Self DW, Lee FS, Tamminga CA, Cooper DC, Gershenfeld HK, Nestler EJ. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang UE, Hellweg R, Gallinat J. BDNF serum concentrations in healthy volunteers are associated with depression-related personality traits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:795–798. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal C, Rafii S, Rafii D, Shahar A, Goldman SA. Endothelial trophic support of neuronal production and recruitment from the adult mammalian subependyma. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:450–464. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi E, Bardsen K, Srebro B, Bramham CR. Acute intrahippocampal infusion of BDNF induces lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the rat dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:496–499. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi K, Jasmin BJ. BDNF is expressed in skeletal muscle satellite cells and inhibits myogenic differentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5739–5749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5398-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Callicott JH, Kolachana BS, Straub RE, Egan MF, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and variation in human cortical morphology. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10099–10102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinborg LH, Adams KH, Svarer C, Holm S, Hasselbalch SG, Haugbol S, Madsen J, Knudsen GM. Quantification of 5-HT2A receptors in the human brain using [18F]altanserin-PET and the bolus/infusion approach. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:985–996. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000074092.59115.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli M, Berkouk K, Prinster A, Landeau B, Svarer C, Balkay L, Alfano B, Brunetti A, Baron JC, Salvatore M. Integrated software for the analysis of brain PET/SPECT studies with partial-volume-effect correction. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:192–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios M, Lambe EK, Liu R, Teillon S, Liu J, Akbarian S, Roffler-Tarlov S, Jaenisch R, Aghajanian GK. Severe deficits in 5-HT2A -mediated neurotransmission in BDNF conditional mutant mice. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:408–420. doi: 10.1002/neu.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Iyo M. Ethnic difference of the BDNF 196G/A (val66met) polymorphism frequencies: the possibility to explain ethnic mental traits. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;126B:122–123. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svarer C, Madsen K, Hasselbalch SG, Pinborg LH, Haugbol S, Frokjaer VG, Holm S, Paulson OB, Knudsen GM. MR-based automatic delineation of volumes of interest in human brain PET images using probability maps. Neuroimage. 2005;24:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Tanaka T, Sutin AR, Deiana B, Balaci L, Sanna S, Olla N, Maschio A, Uda M, Ferrucci L, Schlessinger D, Costa PT., Jr BDNF Val66Met is associated with introversion and interacts with 5-HTTLPR to influence neuroticism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1083–1089. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovska V, Marcussen AB, Vinberg M, Hartvig P, Aznar S, Knudsen GM. Measurements of brain-derived neurotrophic factor: methodological aspects and demographical data. Brain Res Bull. 2007;73:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovska V, Santini MA, Marcussen AB, Thomsen MS, Hansen HH, Mikkelsen JD, Arneberg L, Kokaia M, Knudsen GM, Aznar S. BDNF downregulates 5-HT(2A) receptor protein levels in hippocampal cultures. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovska V, Vinberg M, Aznar S, Knudsen GM, Kessing LV. Whole blood BDNF levels in healthy twins discordant for affective disorder: association to life events and neuroticism. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse EG, Xu B. New insights into the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in synaptic plasticity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]