Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is consistently preceded by its pre-malignant states, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and/or smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). By definition, precursor conditions do not exhibit end-organ disease (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal failure, skeletal lytic lesions, or a combination of these). However, new imaging methods are demonstrating that some patients in the MGUS or SNM category are exhibiting early signs of MM.

Although MGUS/SMM patients are currently defined as low-risk versus high-risk based on clinical markers, we currently lack the ability to predict the individual patient’s risk of progression from MGUS/SMM to MM.

Given that the presence of gross lytic bone lesions is a hallmark of MM, it is reasonable to believe that less severe bone changes defined by more sensitive imaging may be predictive of MM progression. Indeed, since bone disease is such an essential aspect of MM, imaging techniques directed at the detection of early bone lesions, have the potential to become increasingly more useful in the setting of MGUS/SMM.

Current guidelines for the radiological assessment of MM still recommend the traditional skeletal survey, although its limitations are well-documented, especially in early phases of the disease when radiographs can significantly underestimate the extent of bone lesions and bone marrow involvement. Newer, more advanced imaging modalities, with higher sensitivities, including whole-body low-dose computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) are being employed. Also various imaging techniques have been used to provide an assessment of bone involvement and identify extra-osseous disease.

This review emphasizes the current state of the art and emerging imaging methods, which may help to better define high-risk versus low-risk MGUS/SMM. Ultimately, improved imaging could allow more tailored clinical management, and, most likely play an important role in the development of future treatment strategies for high-risk precursor disease.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma-cell malignancy characterized by the presence of end-organ damage such as lytic bone disease, anemia, hypercalcemia, and renal insufficiency. Recent data show that MM is consistently preceded by its precursor states, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, MGUS; and smoldering multiple myeloma, SMM, which by definition, do not exhibit end-organ disease (1, 2).

Based on current diagnostic criteria (2), patients with MGUS and SMM should be followed indefinitely given their life-long risk of progression to MM or related malignancy. On average, the estimated risk of MM progression is 1% per year for MGUS and 10% per year for SMM patients (2). Hopefully, early recognition will improve the outcomes since patients with MM have a median survival of only 3 to 4 years (3).

Standard investigations for the diagnosis of MM include blood tests, serum and urine protein assays, and bone marrow aspiration/biopsy (4). Furthermore, imaging of the skeleton, with the aim to rule out lytic bone lesions, is important to discriminate MM from its precursor states. However, there is increasing recognition that MM is a multifocal disease of the marrow and the bone marrow aspirate of the pelvis may inadequately sample the disease status.

Various imaging techniques have been used for the diagnosis and management of MM, although the current standard radiographic skeletal survey is still a mainstay in many centers due to its low cost, coverage of the skeleton and wide availability. Due to the widespread distribution of myelomatous lesions, development of an imaging modality which can encompass the entire body is of great importance.

The currently available imaging modalities for detection of bone myeloma involvement such as whole-body computed tomography (CT), whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and whole body FDG-PET scanning combined with low-dose CT scan offer the opportunity to precisely stage patients by anatomic and functional techniques and provide higher sensitivity than the standard X-ray skeletal survey. Table 1 lists the different imaging modalities currently available for imaging MM.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages for various imaging modalities used in multiple myeloma and its precursor states (MGUS and SMM)

| Image Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray skeletal Survey |

|

|

| CT |

|

|

| MRI imaging |

|

|

| 99mTc-Sestamibi |

|

|

| PET/CT |

|

|

The Durie-Salmon staging system for MM is based on laboratory values, as well as the number of osteolytic bone lesions determined during a skeletal survey (5), and thus approximately reflects total tumor burden. Recently, the Scientific Advisory Group of the International Myeloma Foundation proposed that MRI and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT be integrated into its classification system (Durie-Salmon PLUS staging system) (6). In some centers, whole-body low-dose CT has replaced the skeletal survey for both diagnosis and follow-up and, where available, whole-body MRI is sometimes used in patients with suspected MM with a negative skeletal survey. Nuclear medicine techniques, such as 18F-FDG PET/CT and 99mTc-sestamibi gamma camera imaging, although not part of the routine evaluation of MM patients, may provide clarification of conventional imaging in selected cases.

According to current diagnostic criteria, in SMM patients an MRI of the spine and pelvis is recommended because it can detect occult lesions and, if present, predict a more rapid progression to symptomatic MM (2). Based on current knowledge, the patterns of spine involvement (focal, diffuse or variegated) is one of the main factors in predicting progression of SMM to the symptomatic form of MM (7, 8).

While less studied, clinical experiences with diffusion-weighted whole body MR imaging (DWI-MRI), Dynamic-Contrast-Enhanced MR imaging (DCE-MRI), and some novel nuclear medicine and PET radiotracers may be able to identify myelomatous bony involvement at an earlier stage.

MORPHOLOGIC IMAGING

Conventional skeletal survey

The traditional skeletal survey has become part of the standard of care for staging and follow-up of bone lesions in MM patients and is still a mainstay due to its low cost and wide availability. However, substantial amounts of bone destruction must be present before it can be seen on a bone survey.

The presence of lytic lesions is a hallmark of MM. These lesions are the result of increased osteoclastic and decreased osteoblastic activity resulting in reduced bone formation (9,10) (Figure 1). In order to perform a ‘complete skeletal survey’ of all areas of possible myeloma involvement, ten to twenty radiographs of the skeleton, including frontal and lateral views of chest, skull, humeri, femora, pelvis and the whole spine, must be obtained. Additional projections may also be necessary. This methodology is not only time consuming, but the quality of the films is highly dependent on patient positioning, requiring an experienced technologist and a cooperative patient. Findings can be subtle, overlap with benign degenerative disease and are subject to inter-reader variability.

Figure 1.

X-ray demonstrates bone lytic lesions in the occipital area of the skull consistent with myeloma involvement.

Almost 80% of patients with MM will have radiological evidence of skeletal involvement on the skeletal survey (11), however, the false-negative rate with skeletal surveys is relatively high (30–70%), leading to a significant underestimation of MM.

In MM precursor disease (i.e. MGUS and SMM), the skeletal survey is negative for lytic lesions (2). However, it is quite possible in many patients that the skeletal survey does not reveal changes because less than 30% of the trabecular bone has been lost and therefore it does not become visible by skeletal survey (12). Moreover, diffuse bone marrow involvement with preserved cancellous bone cannot be identified with conventional X-ray, and this should be assessed with other imaging modalities, such as MRI. Conventional X-ray studies also fail to distinguish osteopenia as a result of bone marrow myeloma infiltration from other more common causes of osteopenia, such as steroid-induced or postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Computed tomography

CT is a morphological imaging method that uses X-rays and computer technology to make cross-sectional images of the body, providing excellent 3D reconstructed images, in ~1 minute and involves no patient repositioning. The resultant anatomic resolution enables CT to localize focal bone destruction with improved sensitivity allowing the detection of small lytic lesions difficult to visualize using the skeletal survey, particularly in the scapulae, rib or sternum (13, 14).

Currently, CT is used primarily as an adjunct to plain films in patients with a negative skeletal survey and high clinical suspicion of MM where it can be used to visualize those areas not well seen on conventional radiographs and it can also delineate soft tissue involvement. As with the skeletal survey, CT may be insufficiently sensitive to detect diffuse bone marrow involvement or osteopenia (15), which typically are better identified with MRI. Since findings on CT can be non-specific for MM, it can be used to guide needle biopsy for histological diagnosis. Implementation of multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT), which uses a detector array instead of a single row of detectors, provides simultaneous acquisition of multiple thin collimated sections resulting in better image resolution. For instance, MDCT was found to be very sensitive in detecting small osteolytic lesions (<5 mm) in the spine, as compared with MRI and PET (15). However, MDCT is insensitive to early focal marrow infiltration (16), because it still requires considerable lysis of bone.

A drawback of CT is that the radiation dose delivered to the patient is higher than with the skeletal survey (effective dose (ED) of 23–37 mSv depending on technique vs 2.4 mSv) (14, 17). Since these studies may be performed in MGUS and SMM patients who are not yet diagnosed with MM, these doses become relevant especially since they may be repeated periodically. Recent studies using low-dose whole body CT scanning, with EDs of approximately 4.1 mSv, have proven to be nearly as effective as conventional dose CT, without the exposure to higher doses of radiation (18).

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI is a non-invasive imaging technique that uses a high magnetic field (typically 1-3T) and radiofrequency pulses to create high resolution 3D images of the body. It has the clear advantage of imposing no ionizing radiation exposure. MRI has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for detecting diffuse and focal MM in the spine and extra-axial skeleton (19). MRI is ideally suited to the evaluation of bone marrow due to its inherent soft tissue contrast. Bone marrow involvement, identified as areas of decreased fat signal on T1-weighted imaging, can be identified with MRI. Short time inversion recovery (STIR) and T2-weighted imaging are the most sensitive sequences for depicting pathologic changes which appear as abnormally high signal regions (20).

MRI is ideally suited to the evaluation of bone marrow due to its inherent excellent soft tissue contrast. MRI was found to be superior to the conventional radiographic diagnosis, particularly with regard to diffuse forms of infiltration, which often escape detection by radiography or even multi-slice CT (21, 22).

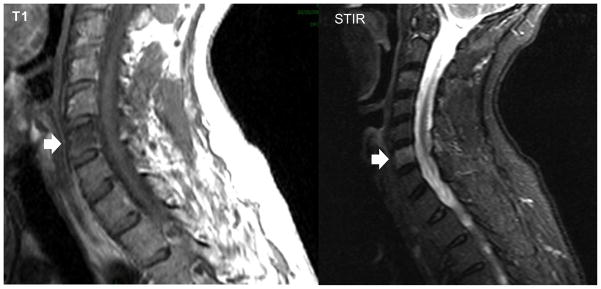

Bone myeloma lesions are hypointense on T1, hyperintense on T2, and hyperintense on STIR and enhance on post-contrast T1 sequences (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MRI scan demonstrates hypointense signal on T1 weighted image and hyperintense signal on STIR sequence in the cervical vertebra, C6, consistent with myeloma involvement.

In order to perform a whole-body MRI, it is necessary to sacrifice some spatial resolution as high resolution MRI with advance sequences are time consuming and cover a limited field of view. Whole-body MRI is recommended in patients with a normal skeletal survey, because it can detect lesions before osteolysis has occurred (23). The major disadvantages are that such studies can be quite long (about 45 min) to cover the at-risk area, are subject to motion and metal artifacts (e.g. hip replacements) and whole body MRI capabilities have not been widely deployed in the imaging community.

MRI has also been shown to permit discrimination of the different bone marrow infiltration patterns, differentiating among normal focal lesions, variegated/salt-and-pepper pattern and diffuse disease in the absence of bone destruction (24). This may have value because a normal appearance and variegated pattern have a better prognosis than the other patterns (25).

Due to the possibility of detecting tumor infiltration earlier with MRI than by conventional radiographs, MRI has been suggested as a tool in the initial staging evaluation of patients with MGUS (5). By definition, MGUS patients do not have abnormalities on MRI examination and the presence of focal lesions may convert the patient from MGUS to MM.

Osteoporosis is a common finding among MGUS patients who have a higher incidence of vertebral fractures compared to the normal population (26). Therefore, sometimes it can be difficult to differentiate MGUS from early MM. To further explore these issues MRI studies have been performed in patients with MGUS. For example, Bellaiche et al found that MRI of the thoracolumbar spine was normal in all patients with MGUS (n=24) compared with only 6 of 44 (13.6%) with newly diagnosed MM (27). In another study, bone marrow abnormalities were detected with MRI imaging in 7 out of 37 patients (19%) with MGUS. All patients with a normal MRI investigation required no treatment after a median follow-up of 30 months, whereas time to progression to MM was significantly shorter for patients with abnormal MRI (28).

The prognostic impact of MR imaging in patients with SMM has been investigated (29,30,31,32). Between 30% and 50% of patients with SMM have an abnormal MRI and the presence of MRI abnormalities is a predictor of earlier progression. In this regard, patients with an abnormal MRI have a median time to progression of less than 1 year, while those with no MRI abnormities have a median time to progression of longer than 3 years (32). In another study, Wang and colleagues (33) also estimated the risk of progression in 72 patients with SMM in whom an MRI of the spine was also performed. A shorter median time to progression was associated with an abnormal MRI (1.5 years vs. 5 years).

In patients with SMM, the pattern of spine involvement (focal, diffuse or variegated) on MR imaging is useful for predicting disease progression to MM (7, 8). The focal pattern is associated with the shortest progression, with an average of 6 months, compared with 16 months for diffuse and 22 months for the variegated pattern (8). The focal pattern is associated with a higher probability of compression fractures and such findings can be reasonably considered to be equivalent to the presence of early lytic bone disease.

FUNCTIONAL AND METABOLIC IMAGING

Morphological imaging techniques, such as X-ray and CT, are able to identify and determine the extent of bone lesions, but not their activity or viability, and they have some limitations when staging early non-measurable lesions or assessing therapy response.

Morphologic lesions can be non-specific for MM and confused with degenerative bone findings or rarefaction related to trauma or fracture. Signal changes in functional imaging techniques may improve specificity by identifying changes in physiology/function of the lesion.

Examples include dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI), gamma scintigraphy (99mTc sestamibi and MDP) and positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F-Fluorodeoxiglucose (FDG) or 18F-Sodium Fluoride (18F-NaF).

Dynamic-contrast-enhanced MR imaging

Dynamic-contrast-enhanced MR imaging (DCE-MRI) combines the advantages of high anatomic resolution of MR with dynamic changes in gadolinium concentration after the intravenous bolus of a low molecular weight MR contrast agent. DCE-MRI parameters reflect vascular permeability and flow within tumors.

While it is not routinely used in MM patients, it may have value when performed in conjunction with morphologic whole-body imaging. DCE-MRI can be used to detect and monitor changes in bone marrow microcirculation as a result of myeloma-induced angiogenesis and changes in tumor blood flow and vascular permeability (34,35). Indeed, the process of angiogenesis has been reported to play a role in the development, growth, and prognosis of hematologic malignancies such as MM (36).

Parameters derived from two compartment modeling of DCE-MRI time-signal curves (e.g. parameters such as Ktrans and Kep) correlate with local complications and the degree of bone destruction in MM. Recently, Hillengass et al. (37) examined patients with MGUS (n=60), asymptomatic MM (n=65), newly diagnostic symptomatic MM (n=75), and healthy controls (n=22) using DCE-MRI of the lumbar spine. Different patterns of microcirculation distribution were identified, ranging from minimal to florid hypervascularity. A gradual increase in microcirculation pattern was identified as disease progressed from its early stages to symptomatic myeloma. Diffuse microcirculation patterns were found in healthy controls, MGUS, and asymptomatic MM (SMM), while a pattern of focal lesions was identified in 42.6% of symptomatic MM patients. MGUS and SMM patients with increased microcirculation patterns on DCE-MRI showed significantly higher bone marrow plasmacytosis compared with patients with a low microcirculation pattern. One MGUS/SMM patient with a pathologic DCE-MRI pattern progressed to MM six months after the abnormal DCE-MRI. While more prospective investigations are needed, it is possible that DCE-MRI may be useful as a marker of progression in patients with MGUS. Another application for this technique is the possibility of identifying patients who may profit from anti-angiogenic therapeutics.

Bone scintigraphy

Traditional bone scintigraphy using 99mTc-bisphosphonates relies on uptake based on the presence of osteoblasts, which are usually lacking in myeloma. Planar bone scintigraphy, as commonly performed, has a lower sensitivity and specificity than conventional radiography in detecting bone lytic lesions, ranging from 40 to 60% (38). While lytic lesions can sometimes be seen as areas of photopenia, bone scintigraphy plays almost no role in the routine staging of myeloma patients.

99mTc-Sestamibi

Another gamma ray emitting radiotracer that has been used for detecting MM is 99mTc-Sestamibi (MIBI) imaging. 99mTc-MIBI is a lipophilic radiotracer whose uptake appears to target cellular mitochondrial activity (39) so that it is increased in neoplastic cells, including those of myeloma (40). The degree of 99mTc-MIBI uptake correlates with the extent of myelomatous involvement as well as serologic markers of disease activity, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein, and beta-2 microglobulin (41). Thus, 99mTc-MIBI closely reflects myeloma disease activity in bone marrow and shows high sensitivity and specificity (92% and 96%, respectively in 68 patients). Conversely, a negative 99mTc-MIBI scan in patients with suspected MM correlates with the absence of disease (42).

Positron emission tomography

PET is another non-invasive functional imaging technique that allows whole-body screening in a single procedure. Clinical PET routinely uses 18F-Fluorodeoxiglucose (FDG), an analogue of glucose that can detect tumors based on their glucose demand, the glucose transport molecules expressed in the cell membrane, and the metabolic activity of the surrounding tissue. It is therefore sensitive for the detection of early bone marrow involvement prior to any identifiable bone changes (Figure 3). Durie et al (43) found that 25% of patients (4 of 25 patients) with negative radiologic surveys had multiple focal lesions on 18F-FDG-PET. Thus, MGUS and SMM are typically negative on 18F-FDG PET (44).

Figure 3.

A patient diagnosed with SMM (i.e. without lesions on skeletal survey). Due to local pain, an 18F-FDG PET scan was conducted. The 18F-FDG PET (a) scan demonstrates increased uptake in the right distal femur, which shows a lytic lesion at the corresponding region on the low-dose CT (b), better visualized on the PET/CT fusion image (c). 18F-FDG PET also shows two additional areas of increased uptake in anterior aspect of the femur, without evidence of bone changes on CT, most likely representing early lytic changes.

Reprinted with permission: Mailankody S, Mena E, Yuan CM, Balakumaran A, Kuehl WM, Landgren O. Molecular and biologic markers of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance to multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010 Oct 20 [Epub].

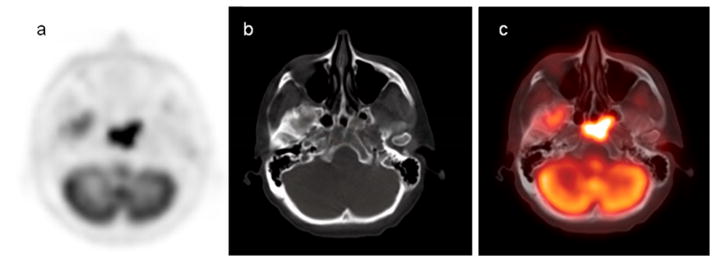

In general, MM has a rather low metabolic activity, and only active lesions will show FDG uptake (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The pattern of marrow infiltration with FDG PET/CT may be focal or diffuse. Schirrmeister et al (45) found a 100% positive predictive value for active myeloma disease in patients with focal or mixed focal/diffuse bone 18F-FDG uptake and 75% in patients with diffuse bone marrow uptake, with sensitivity ranging from 83.8% to 91.9% and specificity from 83.3% to 100% depending on the types of lesions, although the population size was small (n=28 patients had MM). FDG PET can also distinguish between intramedullary and extramedullary lesions in patients with MM (46). Unfortunately, false-negative findings may occur in the presence of subcentimeter lesions, skull lesions, and diffuse disease (simply because the local cell density is too low) or in lesions with low metabolic activity. Coexisting infectious or inflammatory processes are the most common causes of false positives.

Figure 4.

18F-FDG PET/CT scan demonstrates intense hypermetabolic 18F-FDG activity in the base of the skull on the PET image (a), and a bone lytic lesion on the CT scan (b). The combined PET/CT fusion (c) visualizes both functional and morphologic changes of bone myeloma involvement.

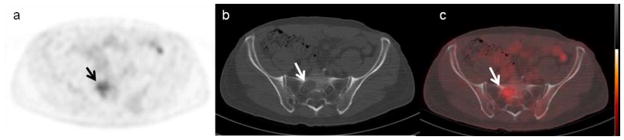

Figure 5.

18F-FDG PET/CT scan demonstrates a low grade metabolic activity in the right sacrum (a), consistent with a lytic lesion on the corresponding low-dose CT (b). The combined PET/CT fusion (c) better visualizes the area of myeloma involvement.

The most significant advantage of 18F-FDG PET is its ability to distinguish between active disease and chronic disease, scar tissue, necrotic tissue, radiation changes, and other benign disease (e.g. fibroma or lipomas). At present, the major disadvantages are cost, availability and radiation dose. 18F-FDG PET/CT scan exposes patients to approximately 14.3 mSv in our institution (6 mSv for a 10 mCi 18F-FDG dose from the PET scan and 8.3 mSv from the low-dose CT).

While a positive 18F-FDG PET reliably predicts active MM, a negative 18F-FDG PET support the diagnosis of MM precursor disease. Durie et al (44) found no false-negative results with FDG in discriminating MGUS from active MM; therefore, a negative 18F-FDG PET is supportive evidence of MGUS.

In a recent study, Shortt et al (47) compared PET with MRI, demonstrating that whole-body MRI had a higher sensitivity and specificity than PET, and the positive predictive value for whole-body MRI was 88%. Combining both imaging techniques yielded a specificity and positive predictive value of 100%. Other studies have suggested that 18F-FDG-PET/CT is more accurate than MR imaging for detecting extramedullary disease, especially in imaging facilities where whole-body MR imaging is not performed (48). Gertz et al. suggested that PET/CT could replace MR imaging in patients with MGUS, because it has been shown that a normal PET/CT reliably predicted stable MGUS (6).

18F-FDG and MRI techniques were also compared with 99mTc-MIBI in another study, but 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI performed better in detecting focal lesions while 99mTc-MIBI and MRI were more effective at identifying diffuse areas of disease (48).

Sodium-Fluoride (18F-NaF) PET/CT

18F-Sodium Fluoride (18F-NaF) is a bone-seeking positron emitting radionuclide, which has been studied since the early 1970s (49). It was superseded by 99mTc-labelled tracers because the high energy of its gamma emissions (511keV), yielded lower quality gamma camera images with technology used at the time. With the widespread implementation of modern PET/CT units, its use as a bone imaging agent is again, quickly regaining momentum.

In contrast to 18F-FDG PET, which is less sensitive in detecting osteoblastic than osteolytic metastases, 18F-NaF seems to have high sensitive for detecting both osteoblastic and lytic bone lesions (50). 18F-NaF PET was reported superior to bone scan and skeletal surveys in detecting malignant bone involvement (51,52,53), likely due to the better spatial resolution of PET and higher count rates. 18F-NaF has better pharmacokinetic characteristics compared with those of 99mTc-MDP; its bone uptake is two-fold higher than 99mTc-MDP, with elevated capillary permeability and faster blood clearance, resulting in a better target-to-background ratio. Regional plasma clearance of 18F-NaF was reported to be 3 to 10 times higher in bone metastases compared with that in normal bone (54). While imposing a similar radiation dose to 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-NaF PET/CT appears to be a promising modality for identifying sites of early osteolysis in MM. Studies to evaluate the efficacy of 18F-NaF PET/CT in identifying early skeletal lesions in MGUS and SMM patients are ongoing.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Additional imaging techniques for accurate detection of early myeloma are under investigation. For instance, a recent study has shown that diffusion-weighted whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (DWI-MRI) may be useful in this setting. DWI-MR is a relatively new functional imaging technology that reflects the random motion of water protons and, therefore, can detect altered diffusion in cells and tissues. Bone marrow packed with myeloma cells has reduced free water diffusion and hence a lower apparent diffusion coefficient. Fenchel et al suggested that DWI-MRI could assess tumor viability in patients with MM as well as predict early response to therapy (55).

Another potentially useful imaging technique for MM is the recently developed PET tracer 3′-fluoro-3′-deoxy-l-thymidine (18F-FLT). 18F-FLT is taken up by cells undergoing DNA synthesis such as occurs in cancers, including hematologic disorders (56). Unfortunately, the baseline bone marrow activity with this agent is quite high due to normal bone marrow activity so that it may be difficult to detect subtle increases in proliferation (i.e. due to high background noise).

PET scanning with radiolabeled amino acids has also been developed. An initial report of 19 patients with MM who underwent PET/CT using a radiolabelled amino acid, 11C-methionine, suggests its potential to image active myeloma. This tracer reflects amino acid metabolism, transport and protein synthesis, which may be a useful biomarker, however, this remains experimental (57).

Based on the hypothesis that angiogenesis is important to the growth of MM, imaging agents that target neovascular endothelium may be useful. For instance, 18F-Fluciclatide (previously named as 18F-AH111585) is an agent that binds to αvβ3 integrins that are commonly overexpressed on the endothelium of tumor vessels (58, 59). This agent may be useful especially since integrins are also found on activated osteoclasts (60).

As newer therapies for MM evolve, the role of radiotracers targeting specific downstream markers of drug effectiveness will become more important.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on current guidelines, the conventional skeletal survey remains the gold standard for the evaluation of osteolytic bone lesions in patients with suspected MM despite its many limitations. Based on the current literature, whole-body MRI and whole-body PET/CT using 18F-FDG are promising in distinguishing patients with definite active myeloma from those with MGUS or SMM.

New molecular PET imaging, such as 18F-Fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), 11C-methionine or 11C-Choline have also shown promise in early clinical trials (54,61,62). There is also evidence emerging that more advanced MR applications such as DWI-MRI and DCE-MRI may be useful. The development of non-invasive imaging techniques to predict progression from MGUS or SMM to active MM is a new area of imaging research. In the future, we believe that more sensitive and more specific imaging techniques will help clinicians to better define high-risk versus low-risk MGUS/SMM. Ultimately, improved imaging will allow more tailored clinical management, and, most likely play an important role in the development of future treatment strategies designed for high-risk precursor disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, Katzmann JA, Caporaso NE, Hayes RB, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Clark RJ, Baris D, Hoover R, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009 May 28;113(22):5412–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Blade J, Merlini G, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia. 2010 Jun;24(6):1121–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1860–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1371–1382. doi: 10.4065/80.10.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durie BGM, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 1975;36:842–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197509)36:3<842::aid-cncr2820360303>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durie BG. The role of anatomic and functional staging in myeloma: description of Durie/Salmon plus staging system. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Jul;42(11):1539–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber DM, Dimopoulos MA, Moulopoulos LA, Delasalle KB, Smith T, Alexanian R. Prognostic features of asymptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1997;97:810–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1122939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blade J, Rosinol L. Smoldering multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;7:237–245. doi: 10.1007/s11864-006-0016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuliani N, Rizzoli V, Roodman GD. Multiple myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology of osteoblast inhibition. Blood. 2006;108:3992–3996. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-026112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terpos E, Sezer O, Croucher P, Dimopoulos MA. Myeloma bone disease and proteasome inhibition therapies. Blood. 2007;110:1098–1104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins CD. Multiple myeloma. Cancer Imaging. 2004 Jan 14;4(Spec No A):S47–53. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2004.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulligan ME. Skeletal abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Radiology. 2005 Jan;234(1):313–4. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahnken AH, Wildberger JE, Gehbauer G, Schmitz-Rode T, Blaum M, Fabry U, et al. Multidetector CT of the spine in multiple myeloma: comparison with MR imaging and radiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002 Jun;178(6):1429–36. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horger M, Claussen CD, Bross-Bach U, Vonthein R, Trabold T, Heuschmid M, et al. Whole-body low-dose multidetector row-CT in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma: an alternative to conventional radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005 May;54(2):289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hur J, Yoon CS, Ryu YH, Yun MJ, Suh JS. Efficacy of multidetector row computed tomography of the spine in patients with multiple myeloma: comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007 May–Jun;31(3):342–7. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000237820.41549.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baur-Melnyk A, Reiser M. Oncohaematologic disorders affecting the skeleton in the elderly. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008 Jul;46(4):785–98. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahnken AH, Wildberger JE, Gehbauer G, Schmitz-Rode T, Blaum M, Fabry U, et al. Multidetector CT of the spine in multiple myeloma: comparison with MR imaging and radiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002 Jun;178(6):1429–36. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horger M, Claussen CD, Bross-Bach U, Vonthein R, Trabold T, Heuschmid M, et al. Whole-body low-dose multidetector row-CT in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma: an alternative to conventional radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005 May;54(2):289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghanem N, Lohrmann C, Engelhardt M, Pache G, Uhl M, Saueressig U, et al. Whole-body MRI in the detection of bone marrow infiltration in patients with plasma cell neoplasms in comparison to the radiological skeletal survey. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(5):1005–14. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirowitz SA, Apicella P, Reinus WR, Hammerman AM. MR imaging of bone marrow lesions: relative conspicuousness on T1-weighted, fat-suppressed T2-weighted, and STIR images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(1):215–21. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghanem N, Lohrmann C, Engelhardt M, Pache G, Uhl M, Saueressig U, et al. Whole-body MRI in the detection of bone marrow infiltration in patients with plasma cell neoplasms in comparison to the radiological skeletal survey. Eur Radiol. 2006 May;16(5):1005–14. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baur-Melnyk A, Buhmann S, Becker C, Schoenberg SO, Lang N, Bartl R, et al. Whole-body MRI versus whole-body MDCT for staging of multiple myeloma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Apr;190(4):1097–104. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker R, Barlogie B, Haessler J, Tricot G, Anaissie E, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in multiple myeloma: diagnostic and clinical implications. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Mar 20;25(9):1121–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baur A, Stäbler A, Bartl R, Lamerz R, Reiser M. Infiltration patterns of plasmacytomas in magnetic resonance tomography [in German] Rofo. 1996;164(6):457–463. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1015689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baur A, Stäbler A, Nagel D, Lamerz R, Bartl R, Hiller E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as a supplement for the clinical staging system of Durie and Salmon? Cancer. 2002;95(6):1334–1345. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepe J, Petrucci MT, Nofroni I, Fassino V, Diacinti D, Romagnoli E, et al. Lumbar bone mineral density as the major factor determining increased prevalence of vertebral fractures in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellaiche L, Laredo JD, Liote F, Koeger AC, Hamze B, Ziza JM, et al. Magnetic resonance appearance of monoclonal gammopathies of unknown significance and multiple myeloma. The GRI Study Group. Spine. 1997;22:2551–2557. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199711010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vande Berg BC, Michaux L, Lecouvet FE, Labaisse M, Malghem J, Jamart J, et al. Nonmyelomatous monoclonal gammopathy: correlation of bone marrow MR images with laboratory findings and spontaneous clinical outcome. Radiology. 1997;202:247–251. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.1.8988218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moulopoulos LA, Dimopoulos MA, Smith TL, Weber DM, Delasalle KB, Libshitz HI, et al. Prognostic significance of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with asymptomatic multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:251–256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van de Berg BC, Lecouvet FE, Michaux L, et al. Stage I multiple myeloma: Value of the MRI of the bone marrow in the determination of prognosis. Radiology. 1996;201:243–246. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.1.8816551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariette X, Zagdanski AM, Guermazi A, Bergot C, Arnould A, Frija J, et al. Prognostic value of vertebral lesions detected by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with stage I multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:723–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimopoulos M, Terpos E, Comenzo RL, Tosi P, Beksac M, Sezer O, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement and guidelines regarding the current role of imaging techniques in the diagnosis and monitoring of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:1545–1556. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M, Alexanian R, Delasalle K, Weber D. Abnormal MRI of spine is the dominant risk factor for early progression of asymptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102:687a. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan B, Thomas AL, Drevs J, Hennig J, Buchert M, Jivan A, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for the pharmacological response of PTK787/ZK 222584, an inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, in patients with advanced colorectal cancer and liver metastases: results from two phase I studies. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Nov 1;21(21):3955–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillengass J, Wasser K, Delorme S, Kiessling F, Zechmann C, Benner A, et al. Lumbar bone marrow microcirculation measurements from dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a predictor of event-free survival in progressive multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Jan 15;13(2 Pt 1):475–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munshi NC, Wilson C. Increased bone marrow microvessel density in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma carries a poor prognosis. Semin Oncol. 2001 Dec;28(6):565–9. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hillengass J, Zechmann C, Bäuerle T, Wagner-Gund B, Heiss C, Benner A, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging identifies a subgroup of patients with asymptomatic monoclonal plasma cell disease and pathologic microcirculation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 May 1;15(9):3118–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolfenden JM, Pitt MJ, Durie BG, Moon TE. Comparison of bone scintigraphy and radiography in multiple myeloma. Radiology. 1980 Mar;134(3):723–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.134.3.7355226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiu ML, Kronauge JF, Piwnica-Worms D. Effect of mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials on accumulation of hexakis (2-methoxyisobutylisonitrile) technetium(I) in cultured mouse fibroblasts. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1646–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mele A, Offidani M, Visani G, Marconi M, Cambioli F, Nonni M, et al. Technetium-99m sestamibi scintigraphy is sensitive and specific for the staging and the follow-up of patients with multiple myeloma: a multicentre study on 397 scans. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:729–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexandrakis MG, Kyriakou DS, Passam FH, Malliaraki N, Christophoridou AV, Karkavitsas N. Correlation between the uptake of Tc99m-sestamibi and prognostic factors in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Lab Hematol. 2002;24:155–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2002.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villa G, Balleari E, Carletto M, Grosso M, Clavio M, Piccardo A, et al. Staging and therapy monitoring of multiple myeloma by 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy: a five year single center experience. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Sep;24(3):355–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durie BG, Waxman AD, D’Agnolo A, Williams CM. Whole-body (18)F-FDG PET identifies high-risk myeloma. J Nucl Med. 2002 Nov;43(11):1457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durie BG. The role of anatomic and functional staging in myeloma: description of Durie/Salmon plus staging system. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Jul;42(11):1539–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schirrmeister H, Bommer M, Buck AK, Müller S, Messer P, Bunjes D, et al. Initial results in the assessment of multiple myeloma using 18F-FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:361–366. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0711-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bredella MA, Steinbach L, Caputo G, Segall G, Hawkins R. Value of FDG PET in the assessment of patients with multiple myeloma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Apr;184(4):1199–204. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shortt CP, Gleeson TG, Breen KA, McHugh J, O’Connell MJ, O’Gorman PJ, et al. Whole-Body MRI versus PET in assessment of multiple myeloma disease activity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Apr;192(4):980–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fonti R, Salvatore B, Quarantelli M, Sirignano C, Segreto S, Petruzziello F, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT, 99mTc-MIBI, and MRI in evaluation of patients with multiple myeloma. J Nucl Med. 2008 Feb;49(2):195–200. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blau M, Ganatra R, Bender MA. 18 F-fluoride for bone imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 1972;2:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(72)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schirrmeister H, Glatting G, Hetzel J, Nüssle K, Arslandemir C, Buck AK, et al. Prospective evaluation of the clinical value of planar bone scans, SPECT, and (18)F-labeled NaF PET in newly diagnosed lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1800–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cook GJ, Fogelman I. The role of positron emission tomography in skeletal disease. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:50–61. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.18746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schirrmeister H, Guhlmann A, Kotzerke J, Santjohanser C, Kühn T, Kreienberg R, et al. Early detection and accurate description of extent of metastatic bone disease in breast cancer with fluoride ion and positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2381–2389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Mishani E, Lievshitz G, Lerman H, Leibovitch I. The detection of bone metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer: 99mTc-MDP planar bone scintigraphy, single- and multi-field-of-view SPECT, 18Ffluoride PET, and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:287–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blake GM, Park-Holohan SJ, Cook GJ, Fogelman I. Quantitative studies of bone with the use of 18F-fluoride and 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:28–49. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.18742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fenchel M, Konaktchieva M, Weisel K, Kraus S, Claussen CD, Horger M. Response Assessment in Patients with Multiple Myeloma during Antiangiogenic Therapy using Arterial Spin Labeling and Diffusion-Weighted Imaging A Feasibility Study. Acad Radiol. 2010 Sep 1; doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.08.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agool A, Schot B, Jager P, Vellenga E. 18F-FLT PET in hematologic disorders: a novel technique to analyze the bone marrow compartment. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1592–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dankerl A, Liebisch P, Glatting G, Friesen C, Blumstein NM, Kocot D, et al. Multiple myeloma: molecular imaging with 11C-methionine PET/CT: initial experience. Radiology. 2007;242:498–508. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kenny LM, Coombes RC, Oulie I, Contractor KB, Miller M, Spinks TJ, McParland B, Cohen PS, Hui AM, Palmieri C, Osman S, Glaser M, Turton D, Al-Nahhas A, Aboagye EO. Phase I trial of the positron-emitting Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide radioligand 18F-AH111585 in breast cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2008 Jun;49(6):879–86. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.049452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morrison MS, Ricketts SA, Barnett J, Cuthbertson A, Tessier J, Wedge SR. Use of a novel Arg-Gly-Asp radioligand, 18F-AH111585, to determine changes in tumor vascularity after antitumor therapy. J Nucl Med. 2009 Jan;50(1):116–22. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beaulieu V, Da Silva N, Pastor-Soler N, Brown CR, Smith PJ, Brown D, Breton S. Modulation of the actin cytoskeleton via gelsolin regulates vacuolar H+-ATPase recycling. J Biol Chem. 2005 Mar 4;280(9):8452–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nanni C, Zamagni E, Cavo M, Rubello D, Tacchetti P, Pettinato C, et al. 11C-choline vs. 18F-FDG PET/CT in assessing bone involvement in patients with multiple myeloma. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:68–75. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishizawa M, Nakamoto Y, Suga T, Kitano T, Ishikawa T, Yamashita K. 11C-Methionine PET/CT for multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol. 2010 Jun;91(5):733–4. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]