Abstract

Background

Measurement of cortisol in hair is an emerging biomarker for chronic stress in human and nonhuman primates. Currently unknown, however, is the extent of potential cortisol loss from hair that has been repeatedly exposed to shampoo and/or water.

Methods

Pooled hair samples from 20 rhesus monkeys were subjected to five treatment conditions: 10, 20, or 30 shampoo washes, 20 water-only washes, or a no-wash control. For each wash, hair was exposed to a dilute shampoo solution or tap water for 45 s, rinsed 4 times with tap water, and rapidly dried. Samples were then processed for cortisol extraction and analysis using previously published methods.

Results

Hair cortisol levels were significantly reduced by washing, with an inverse relationship between number of shampoo washes and the cortisol concentration. This effect was mainly due to water exposure, as cortisol levels following 20 water-only washes were similar to those following 20 shampoo treatments.

Conclusions

Repeated exposure to water with or without shampoo appears to leach cortisol from hair, yielding values that underestimate the amount of chronic hormone deposition within the shaft. Collecting samples proximal to the scalp and obtaining hair washing frequency data may be valuable when conducting human hair cortisol studies.

Keywords: Hair, cortisol, Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, Rhesus monkey, Shampoo

1. Introduction

Assessment of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis activity in both humans and animals commonly involves sampling of blood or saliva. Measures from these fluid compartments reflect short-term assessments and are subject to the potentially confounding influences of circadian variation and in some cases, the stress of the sample collection procedure. Although measurement of corticosteroid excretion in urine and feces obviates some of these problems, such approaches still restrict investigators to a time frame of around 24 h or less.

Recent research supports the possibility that measurement of cortisol in hair can provide an integrated assessment of chronic HPA axis activity over a period of months that is not subject to the influences of circadian variation or the stress of sample collection [1,2]. Validation of this approach has been provided by studies in our laboratory conducted using rhesus monkey hair [3]. These studies showed that (1) the material measured in monkey hair reacted identically to authentic cortisol in an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), (2) the large majority of the immunoreactive cortisol in hair resisted removal by brief solvent washes, suggesting that most of the cortisol was embedded in the hair shaft rather than coating the outside of the shaft (e.g., deposited on the surface from dried sweat), (3) cortisol extraction from the interior of the hair was maximized by pulverizing the samples using a ball mill, and (4) cortisol levels did not vary systematically as a function of location on the hair shaft (distal vs. proximal to the scalp) in animals maintained under standard colony conditions (i.e., without the imposition of a stress manipulation).

Additional validation of hair as a suitable matrix for assessing long-term changes in HPA activity comes from the demonstration that hair cortisol levels are elevated after exposure to a stressor or other conditions associated with elevated circulating cortisol concentrations. For example, we recently found that rhesus monkeys subjected to a mandatory relocation had increased hair cortisol following the move [4]. In human subjects, hair cortisol levels have been shown to be sensitive to employment status [5], chronic pain [6], and pregnancy [7].

Although measuring cortisol in hair has great potential for assessing long-term HPA activity noninvasively, the fact that hair shafts are continuously exposed to the external environment raises some concern. Indeed, two recent segmental analyses that examined either 1- or 3-cm long segments of human hair both demonstrated that cortisol concentration decreased as a function of distance from the scalp [7,8]. This finding is in contrast to the lack of a segmental effect in rhesus monkeys maintained under constant conditions. It is possible that the segmental effect observed in human studies is, at least in part, caused by repeated washing of the hair and possibly also by the use of styling products and/or dyes. However, there are no previous reports on the effects of hair washing on cortisol concentrations under controlled conditions. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the effects on cortisol levels of repeatedly exposing hair samples to a shampoo solution or to water alone.

Because of the obvious difficulty inherent in obtaining adequate lengths of human hair that had never been washed, we chose to perform the study with rhesus monkey hair. Macaques are a reasonable model for demonstrating the effects of washing on cortisol concentrations due to the known similarities between macaque and human hair [9]. For example, both types of hair show a mosaic growth pattern characterized by independence of phase across nearby follicles and the tendency of follicles to grow in groups of 3 (range 2-7). Furthermore, daily hair growth rates are about the same (~ 0.37 mm in humans vs. 0.33-0.38 mm in macaques). We hypothesized that the findings of the previous segmental analyses [7,8] were, at least in part, due to repeated hair washing that caused cortisol to leach from the hair shaft. Consequently, we predicted that hair cortisol content would decline systematically as a function of the number of washes with a shampoo-containing solution. In addition, we predicted that washing with water alone would also significantly reduce hair cortisol content because of the known ability of water to causing swelling of the hair shaft [10].

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Hair was obtained during routine health exams from 18 adult female and 2 adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) ranging in age from 8 to 27 y (mean = 14.5 y) (Table 1). The monkeys were maintained in a large 5-acre outdoor enclosure containing several corncrib structures and an attached indoor housing environment at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Laboratory of Comparative Ethology in Poolesville, Maryland. The monkeys’ diet consisted of Purina Monkey Chow supplemented with fresh fruits and vegetables. Water was available ad libitum. The research described in this report was approved by the NICHD Animal Care and Use Committee, performed in accordance with the NIH Guide and Use of Laboratory Animals, and complied with the Animal Welfare Act.

Table 1.

Identification number, age, and sex of monkeys assigned to each pool and mean age of animals in each pool.

| Animal ID | Age (y) | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pool 1 | |||

| 23 | 27.0 | F | |

| T27 | 8.8 | F | |

| 39C | 18.8 | F | |

| R32 | 9.8 | F | |

| R47 | 9.7 | F | |

| Mean = 14.8 y | |||

| Pool 2 | |||

| 27B | 21.8 | M | |

| T19 | 8.8 | F | |

| 43C | 17.8 | F | |

| R27 | 9.8 | F | |

| I31 | 13.6 | F | |

| Mean = 14.4 y | |||

| Pool 3 | |||

| 34C | 20.8 | F | |

| R49 | 9.6 | M | |

| D17 | 16.8 | F | |

| P11 | 10.8 | F | |

| K13 | 12.8 | F | |

| Mean = 14.2 y | |||

| Pool 4 | |||

| 37C | 18.8 | F | |

| D43 | 16.6 | F | |

| P02 | 10.9 | F | |

| G43 | 14.6 | F | |

| M05 | 11.8 | F | |

| Mean = 14.5 y | |||

2.2 Sample collection and pooling

Hair was gently shaved from the nape of the neck using the collection procedure described by Davenport et al. [3]. Samples were collected in February of 2008, placed in aluminum foil packets, and shipped to the University of Massachusetts Amherst where they were maintained at 4°C or colder. These particular hair samples were not collected for the purposes of this research; however, there was a sufficient amount of hair left over from previous studies for use in our experiment. The hair sample remnants were combined to create four separate pools, each consisting of hair from five different monkeys (Table 1). Hair pooling was done in order to (1) provide a sufficient sample size for all treatment conditions to be performed on the same material (i.e., pool), and (2) constitute multiple replicates (each hair pool was considered to be one replicate) of each wash condition. The pools were balanced as closely as possible for both age and gender. In order to ensure that each pool was thoroughly mixed, hair from the five monkeys was combined and gently combed to distribute the different samples. Next, each pool was subdivided into five different treatment conditions: a no-treatment control condition, a 20 water-only wash condition, and conditions involving 10, 20, or 30 washes with an aqueous shampoo solution.

2.3 Hair treatments

Pooled hair samples weighing approximately 250 mg were placed in disposable 15-ml screw-cap plastic culture tubes. For the shampoo conditions, each treatment began with addition of 10 ml of a room-temperature solution of Pantene Pro-V®, a popular over-the-counter human shampoo, dissolved in tap water. The shampoo concentration was 10%, which is commonly used in shampoo testing studies (e.g., see http://www.dsm.com/en_US/downloads/dnpsa/D_Panthenol.pdf). The tube was then capped and the sample was gently washed by repeated inversion for 45 s. This exposure time was determined by an informal survey of female acquaintances of one of the authors (AFH) in which the participants were asked to estimate how much time their hair was in contact with the shampoo solution when they washed their hair. The shampoo solution was then decanted, after which 10 ml of room-temperature tap water was added and the tube was recapped and gently inverted for 30 s before being decanted again. This rinse procedure was repeated three additional times for a total of four post-wash rinses. Four rinses were found to be necessary to remove all visual traces of the soapy shampoo solution from the sample. Finally, the samples were thoroughly blow-dried while still in the tube using a standard hair drier (low heat setting) for no longer than 5 min or until dry. Blow drying of the samples was carried out because this method is frequently used by humans, especially women, to dry their hair after washing. This cycle of washing, rinsing, and blow-drying was performed a total of 10, 20, or 30 times, according to the treatment condition to which each sample was assigned. For the water-only condition, the procedures were identical except that 10 ml of tap water was substituted for the 10% shampoo solution at each wash step. The water-only condition was performed with 20 washes in order to provide a direct comparison to the 20 shampoo wash condition.

2.4. Hair cortisol analysis

After all the treatments had been performed, the samples were processed and analyzed for cortisol content using previously described methods [3]. Briefly, the samples were washed twice with isopropanol, air-dried, and then powdered using a ball mill. Approximately 50 mg of powdered hair from each sample was extracted overnight with methanol. Extracts were evaporated, reconstituted in assay buffer, and then analyzed in duplicate for cortisol by enzyme immunoassay (Salimetrics, State College, PA). All samples were analyzed together in a single assay. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 1.8%.

2.5. Data analysis

Because each hair pool was represented in all five treatment conditions, the data were initially analyzed using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in order to determine the overall effects of the shampoo or water washing treatments. This was followed by a linear trend analysis involving the no treatment control and the three shampoo conditions to ascertain the effect of increasing number of shampoo treatments on hair cortisol levels. Finally, paired t-tests were performed to (1) determine the effect of water washing alone by comparing this condition against the no treatment control and against the 20 shampoo wash condition and (2) determine the effect of repeated shampoo washing by comparing samples exposed to 10 shampoo washes to samples exposed to 30 shampoo washes.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effects of shampoo and water alone washing on hair cortisol

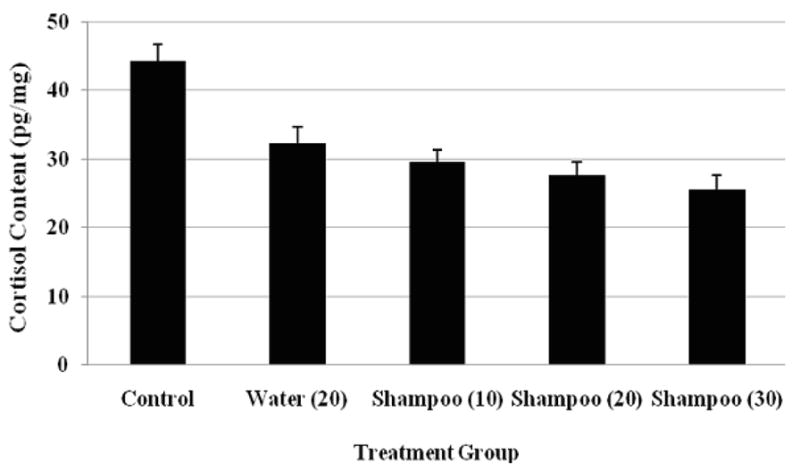

The repeated measures ANOVA identified an overall effect of treatment on hair cortisol concentrations (F(4,15)=21.44, p<0.001; see Figure 1, Table 2). The linear trend analysis revealed a significant linear relationship among the no-wash control and the shampoo treated samples, such that more washes with shampoo were associated with more cortisol loss (F(3,12)=39.74, p=0.008). Further analysis using post-hoc paired t-tests showed a significant difference between samples treated with 20 water-only washes and the no treatment control (t(3)=4.84, p=0.017), but no significant difference between the 20 water-only wash condition and the 20 shampoo wash condition (t(3)=1.58, p=0.213). An additional paired t-test revealed a significant difference between samples exposed to 10 shampoo washes and samples exposed to 30 shampoo washes (t(3)=7.47, p=0.005).

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) hair cortisol content (pg/mg) across the four pools as a function of treatment condition: no-treatment control, 20 water-only washes, and 10, 20, or 30 shampoo washes.

Table 2.

Changes in hair cortisol content (pg/mg) in each pool as a function of treatment condition.

| Control | Water(20) | Shampoo(10) | Shampoo(20) | Shampoo(30) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool 1 | 48.7 | 39.1 | 34.8 | 28.7 | 31.3 |

| Pool 2 | 39.1 | 28.0 | 28.2 | 29.9 | 24.8 |

| Pool 3 | 48.1 | 29.8 | 27.9 | 22.0 | 22.2 |

| Pool 4 | 41.2 | 32.1 | 27.6 | 30.0 | 24.1 |

3.2 Interpretation and conclusions

Our data show that repeatedly exposing rhesus monkey hair to an aqueous shampoo solution reduces hair cortisol content, presumably by leaching a portion of the hormone from the interior of the hair shaft. Moreover, the amount of cortisol remaining after washing was inversely related to the number of shampoo exposures. These findings have several important implications for the measurement of cortisol in humans. First, it seems likely that the values obtained in human studies underrepresent, to an unknown degree, the amount of cortisol that was actually deposited in the hair during the time period represented by the samples. Second, the results suggest that human subjects who wash their hair more frequently may lose more cortisol from the hair than subjects who wash their hair less frequently (all else being equal). Finally, the loss of cortisol due to washing is probably a major contributor to the segmental effect observed in human hair [7,8] in which cortisol concentrations were progressively lower in the more distal segments. Assuming that hair grows approximately 1 cm per month and that humans typically wash their hair at least several times per week, hair located several centimeters from the scalp might be exposed to well over 36 shampooing events, which now appears to be a significant contributor to variation in cortisol levels.

Somewhat surprisingly, the washing effect was primarily due to the water exposure, inasmuch as samples washed the same number of times with either water or a shampoo solution did not differ significantly in cortisol content. If, indeed, repeated water exposure in the absence of shampoo similarly removes cortisol from hair, then this is a limitation that must also be recognized when measuring hair cortisol in animals living outdoors that are either exposed repeatedly to rainfall or spend significant amounts of time in or under the water. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that the loss of cortisol in the washed hair was a consequence of thermal degradation due to the use of a hair dryer on the samples. However, this explanation seems highly unlikely because cortisol does not decompose until heated to 220°C [11], and we took care not to overheat the samples during the blow-drying step.

Our findings suggest possible strategies and considerations when using hair as a matrix for cortisol determinations. Depending on the hypothesis being tested, researchers should collect hair samples as close to the scalp as possible in order to most accurately assess hair cortisol levels in relation to the variables of interest. Furthermore, hair samples should be of the same length in order to reduce variation in shampoo and water exposure. Because, shampooing rates might still vary considerably, we recommend that researchers collect information on frequency of shampooing to use as a covariate in any data analysis. Our findings also provide a caveat when comparing hair cortisol levels in animal populations housed in different environments. For example, exposure to water might be significantly higher in free ranging rhesus monkeys compared to laboratory housed monkeys, leading to a finding of lower cortisol concentrations in the free-ranging animals that might be due to increased water exposure rather than to an effect of the housing condition per se. However, these issues should not affect animals studied under the living same conditions. Hair has become an increasingly valuable matrix for assessing chronic levels of HPA axis activity; however, an understanding of the various environmental influences acting on the hair shaft is important for interpreting one’s results.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by a grant RR11122 awarded to M.A.N. from the National Institutes of Health and by the Division of Intramural Research, NICHD and grant RR000168 awarded to the New England Primate Research Center.

Abbreviations

- HPA

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- EIA

Enzyme immunoassay

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Development

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gow R, Thomson S, Rieder M, Van Uum SHM, Koren G. An assessment of cortisol analysis in hair and its clinical applications. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;196:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauvé B, Koren G, Walsh G, Tokmakejian S, Van Uum SHM. Measurement of cortisol in human hair as a biomarker of systemic exposure. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30:E183–E191. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i5.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davenport MD, Tiefenbacher S, Lutz CK, Novak MA, Meyer JS. Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;147:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport MD, Lutz CK, Tiefenbacher S, Novak MA, Meyer JS. A rhesus monkey model of self injury: effects of relocation stress on behavior and neuroendocrine function. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dettenborn L, Tietze A, Bruckner F, Kirschbaum C. Higher cortisol content in hair among long-term unemployed individuals compared to controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Uum SHM, Sauve B, Fraser LA, Morley-Forster P, Paul TL, Koren G. Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: a novel biomarker for stress. Stress. 2008;11:483–488. doi: 10.1080/10253890801887388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirschbaum C, Tietze A, Skoluda N, Dettenborn L. Hair as a retrospective calendar of cortisol production—increased cortisol incorporation into hair in the third trimester of pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao W, Xie Q, Jin J, et al. HPLC-FLU detection of cortisol distribution in hair. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mottet NK, Body RL, Wilkens V, Burbacher TM. Biological variables in the hair uptake of methylmercury from blood in the macaque monkey. Environ Res. 1987;42:509–523. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(87)80218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins CR. Chemical and physical behavior of human hair. fourth. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chemical Book. [7/19/2010]; http://www.phamacopeia.cn/v29240/usp29nf24s0_alpha-2-17.html.