Abstract

Aims

Although useful, percutaneous left atrial ablation for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) does not eliminate atrial fibrillation (AF) in all patients. The ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAEs) has been proposed as an adjunctive strategy to improve the maintenance of sinus rhythm after PVI. Our objective was to analyse the efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation.

Methods and results

We meta-analysed six randomized controlled trials (total, n= 538) using random-effects modelling to compare PVI (n= 291) with PVI plus CFAE ablation (PVI + CFAE) (n= 237). The primary outcome was freedom from AF or other atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATs) after a single ablation with or without antiarrhythmic drugs. Following a single ablation, PVI + CFAE improved the odds of freedom from any AF/AT compared with PVI alone (odds ratio 2.0, 95% confidence interval 1.04–3.8, P = 0.04) at ≥3-month follow-up. There was moderate heterogeneity among trials (I2= 63.0%). Complex fractionated atrial electrogram ablation significantly increased mean procedural (178.5 ± 66.9 vs. 331.5 ± 92.6 min, P< 0.001), mean fluoroscopy (59.5 ± 22.2 vs. 115.5 ± 35.3 min, P< 0.001), and mean radiofrequency (RF) energy application times (46.9 ± 36.6 vs. 74.4 ± 43.0 min, P< 0.001).

Conclusions

Pulmonary vein isolation followed by adjunctive CFAE ablation is associated with increased freedom from AF after a single procedure. Adjunctive CFAE ablation increased procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF application times, and the risk/benefit profile of adjunctive CFAE ablation deserves further evaluation with additional studies and longer-term follow-up.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Catheter ablation, Meta-analysis, Complex fractionated electrograms, Pulmonary vein isolation

Introduction

Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AF) is an evolving treatment strategy for the maintenance of sinus rhythm, offering a reasonable therapy alternative for patients with symptomatic, drug-refractory AF. Recent reports suggest that 65–75% of patients are free of AF at 1 year after a single procedure.1–10 New catheter ablation strategies include ablation for atrial substrate modification in addition to targeting and eliminating AF triggers associated with the pulmonary veins.11 The ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAEs) in addition to PVI has been proposed as one such strategy to improve the maintenance of sinus rhythm.12 Whereas CFAE ablation as a sole primary therapy has not demonstrated reproducible efficacy,13,14 many experts advocate a combined approach that eliminates AF triggers associated with the pulmonary veins via pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) together with additional ablation targeting CFAEs to modify the atrial substrate for AF.

Several observational studies have demonstrated improved outcomes with adjunctive CFAE ablation, particularly for paroxysmal AF; however, reported successes with this approach are not uniform.15–20 Specifically, several randomized clinical trials of PVI vs. PVI plus adjunctive CFAE ablation (PVI + CFAE) published in the last year report results with relatively small sample sizes consisting of different patient populations and using various laboratory techniques.21–25 As such, the relative efficacy of PVI + CFAE ablation compared with PVI alone remains unclear. In addition to the limited availability of outcomes information on adjunctive CFAE ablation from prospective multicentre randomized trials, the strategy of targeting CFAEs during left atrial ablation has been reported in some studies to be associated with increased rates of post-ablation organized atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATs) ranging from 10 to 25%.13,18,24 The goal of this study is to synthesize the available prospective randomized data comparing PVI alone to PVI plus adjunctive CFAE ablation to help evaluate the risks and benefits of adjunctive CFAE ablation compared with stand-alone PVI for the treatment of drug-refractory AF.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of MEDLINE was conducted with the following terms: ‘atrial fibrillation’ AND ‘fractionated electrograms'. The same query was conducted in (i) Cochrane database, (ii) FDA web-portal, and (iii) clinicaltrials.gov. The bibliographies of identified studies were reviewed for additional studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Eligibility and data abstraction

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which patients with AF referred for catheter ablation were randomized to undergo stand-alone PVI vs. PVI + CFAE ablation. Additional inclusion criteria included follow-up ≥3 months, full-length peer-reviewed publication in English, and a study population >18 years old.

All studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were independently reviewed with standardized data abstraction by two investigators (M.H.K. and J.P.P.). A third investigator (T.D.B.) adjudicated any discrepancies. The results of the MEDLINE query included those reports identified by other search methods (www.fda.gov, clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane database, and bibliographies). Abstracted data included eligibility criteria, baseline characteristics, study design (including treatment and control arms), follow-up, and outcomes.

The primary outcome of interest was freedom from AF or AT after a single ablation procedure with or without the ongoing use of antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs). When available, data were also abstracted on pre-specified secondary measures of the efficacy and safety of the catheter ablation procedure including: repeat ablation; incidence of post-procedure ATs; procedural times [total, fluoroscopy, and radiofrequency (RF) energy application]; complications (pericardial effusion, pericarditis, pulmonary vein stenosis, and vascular/bleeding complications); and post-ablation AAD use. Outcomes were analysed by the intention-to-treat principle.

Statistical analysis

Random-effects modelling according to the method of DerSimonian and Laird26 was used to evaluate the effects of CFAE ablation on the primary outcome. Sensitivity analyses were performed based on AF subgroups (paroxysmal vs. persistent) as well as serial exclusion of each individual trial. The patient was the individual unit of analysis (as opposed to person years) and the measure of treatment effect for the primary endpoint was reported by odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity between studies was determined using the I2-statistic. All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis SoftwareTM (BIOSTAT, Englewood, NJ, USA).

Baseline characteristics and secondary outcomes of the stand-alone PVI group were compared with the PVI + CFAE group. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables are presented as means for central tendency measurement and standard deviation for variance reporting. Categorical measures were compared using Fisher's exact test and continuous data were compared using Student's t-test. Statistical testing was two-tailed and statistical significance was declared at P < 0.05.

Results

Search results

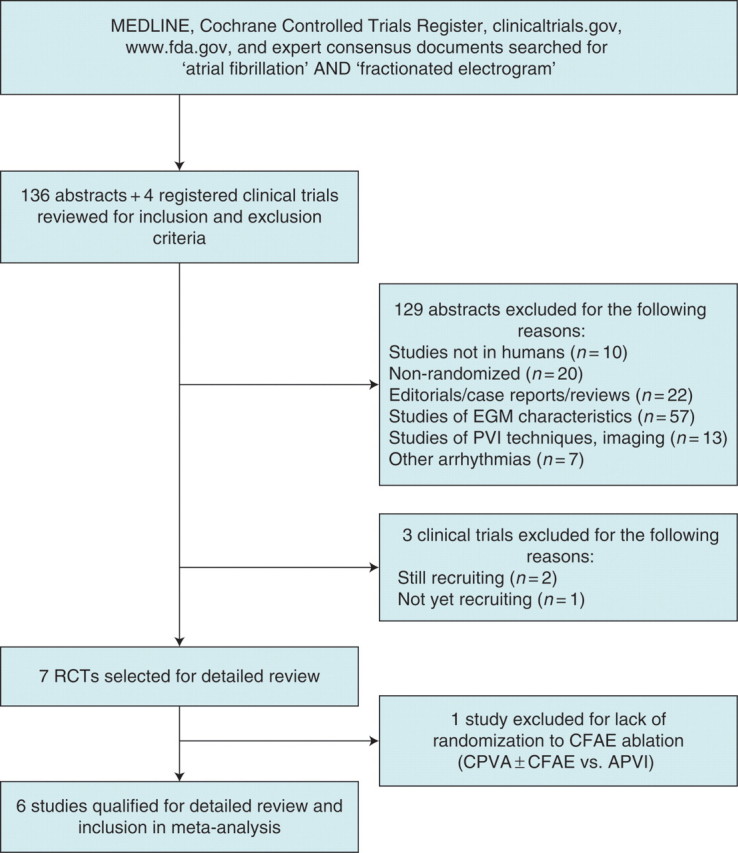

After searching MEDLINE, the Cochrane database, fda.gov, clinicaltrials.gov, and the bibliographies of expert consensus documents,27,28 we identified 136 abstracts and 4 registered clinical trials, which were reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among this group of abstracts, 129 were excluded for reasons listed in Figure 1. For the remaining seven studies, full manuscripts were reviewed and six trials were included in the analysis. One recently published trial was excluded because patients were not randomized to receive CFAE ablation, but were randomized to circumferential PVI (CPVA) with possible supplemental CFAE ablation vs. potential-guided antral PVI (APVI) and as such, there was no way to isolate the treatment effect of adjunctive CFAE ablation for evaluation.29

Figure 1.

QUOROM flow diagram for the meta-analysis.

Trial characteristics and study quality

We identified six RCTs of PVI with and without adjunctive CFAE ablation for inclusion, which enrolled 538 patients (Table 1). Four of the studies were published since 2009.21,22,24,25 Two studies enrolled patients with long-standing persistent AF,23,24 three studies enrolled patients with paroxysmal AF,21,22,30 and the most recently published study enrolled both patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF. Of note, the Oral et al.30 study from 2004 only included the subgroup of paroxysmal AF patients who had induction of AF with rapid pacing after CPVA. Although all studies examined the primary endpoint of freedom from AF/AT, post-procedure follow-up periods (3 to 16.4 ± 1.3 months) and post-procedure AAD use varied widely (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of RCTs included in meta-analysis

| Study | Journal | Year | Centre | Total (n) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Control arm | Specified primary endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deisenhofer et al.21 | J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol | 2009 | Germany | 98 | Age 18–80 years; symptomatic PAF with episodes lasting up to 7 days and with ≥4 episodes per month; failed therapy with ≥1 Class I or III AAD | Intracardiac thrombi documented by TEE; LVEF <35%; history of MI or cardiac surgery in previous 3 months; prior ablation procedures for AF | Segmental PVI alone | Freedom from AT >30 s duration on a 7-day Holter 3 months post-procedure in combination with freedom from symptomatic AF/AT 3-months post-ablation |

| Di Biase et al.22 | Circ ArrhythmElectrophysiol | 2009 | Multicentre | 103 | PAF 1 year; refractory to ≥2 AADs; presented to EP lab with spontaneous AF | Prior ablation | APVI alone | Freedom from AF defined as no episodes of AF/AT with or without AADs that lasted more than 1 min at 1-year follow-up |

| Elayi et al.23 | Heart Rhythm | 2008 | Multicentre | 144 | Long-standing history of AF; failed to maintain SR with ≥2 AADs; AF duration >1 year with ≥1 failed DCCV after >1 week on AADs referred for first-time ablation from January 2005 to February 2006 | Paroxysmal or persistent AF; <18 years old; >80 years old; previous RF ablation in left atrium or surgical Maze | APVI or CPVA | Freedom from AF/AT defined as no episodes of AF/AT >1 min during follow-up. AF/AT occurring during 2-month blanking period after first procedure while patient was on AADs were not considered recurrence |

| Oral et al.30 | Circulation | 2004 | Ann Arbor, MI, USA | 60 | AF inducible by atrial pacing after left atrial circumferential ablation for symptomatic, drug-resistant PAF | NR | CPVA | Freedom from AF defined at 6 months without AAD |

| Oral et al.24 | J Am Coll Cardiol | 2009 | Ann Arbor, MI, USA | 100 | Long-lasting persistent AF | Prior ablation | APVI alone | Freedom from symptomatic or asymptomatic AF and other ATs without AADs after single procedure |

| Verma et al.25 | Eur Heart J | 2010 | Multicentre | 100 | Drug-refractory, high-burden paroxysmal (episodes >6 h, >4 in 6 months) or persistent AF | ‘Permanent AF', AF secondary to an obvious reversible cause, inadequate anticoagulation, LA thrombus on TEE, contraindications to systemic anticoagulation with heparin or Coumadin, prior AF ablation, LA size >55 mm, pregnant or possibly pregnant | CPVA alone | Freedom from AF recurrence from months 3 to 12 post-ablation after 1 or 2 procedures on and off AADs |

DCCV, direct current cardioversion; EKG, electrocardiogram; LA, left atrium; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NR, not reported; RF, radiofrequency; TEE, transoesophageal echocardiogram.

Table 2.

Study follow-up protocols

| Study | Duration of anticoagulation before ablation (weeks) | Duration of anticoagulation after ablation (months) | AAD post-procedure | Follow-up protocol | Mean duration of follow-up for primary endpoint (months) |

Mean duration of follow-up after last procedure (months) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | |||||

| Deisenhofer et al.21 | 6 | NR | No AADs until 3-months post-procedure | 1- and 3-month outpatient clinic visit post-procedure, then q3 months; intensive questions for arrhythmia symptoms; 24-h Holter 1-month post-ablation; 7-day Holter 3-months post-ablation with MRI or CT scan to rule out PV stenosis; TTE 1-month post-ablation | 3 | 3 | 19 ± 8 | 19 ± 8 |

| Di Biase et al.22 | NR | Warfarin continued for minimum of 6 months | Pre-procedure AAD (except amiodarone) continued for 8 weeks post-procedure | 3-month outpatient clinic visit, then q3 months; event recorder for 5 months with 4 recordings per week even if asymptomatic and any time they felt symptoms; 48-h Holter obtained at 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, and 15-month post-procedure | 13.7 ± 2.2 | 13.7 ± 2.2 | 9 ± 7 | 9 ± 7 |

| Elayi et al.23 | NR | 12 months minimum | Discontinued after 2 months | Event recorders for the first 6 months with 4 recordings per week even if asymptomatic and any time with symptoms; outpatient visits with 12-lead EKG, 48-h Holter at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months | 16.7 ± 1.6 (CPVI);16.4 ± 1.1 (APVI) | 16.2 ± 1.2 | 14.8 ± 3.6 (CPVI);14.6 ± 3.8 (APVI) | 14.9 ± 3.0 |

| Oral et al.30 | NR | Heparin for 5 days, warfarin for 3 months | Class I or III AAD for 8–12 weeks post-procedure | 3-month outpatient clinic visit post-procedure, then q6 months; NP follow-up q4 weeks; patients instructed to call whenever symptoms in which case an event recorder was used to document rhythm at the time of symptoms | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Oral et al.24 | NR | Warfarin discontinued after 6 months if SR | Pre-procedure AAD continued for 8–12 weeks post-procedure | 3-month outpatient clinic visit post-procedure, then q3–6 months; 30-day auto-triggered event monitor 6-months post-procedure; patients instructed to call if symptoms | 10 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 | 9 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 |

| Verma et al.25 | 4 | 3 months minimum | AADs continued for 2 months post-procedure, but discontinued in all patients after 2 months | 3-, 6-, and 12-month outpatient clinic visits; monthly telephone interviews; 12-lead EKG and 48-h Holter at 3-, 6-, and 12-months follow-up visits; external loop recorders (minimum 2 weeks) and or transtelephonic monitors for any patient-reported symptoms outside of routine follow-ups; interrogation of implanted devices when applicable; routine spiral CT or MRI of chest within 6 months to assess for PV stenosis | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

CT, computed tomography; EKG, electrocardiogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NP, nurse practitioner; NR, not reported; PV, pulmonary vein; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

Five trials randomized patients to some form of PVI (antral or circumferential) as the control group vs. PVI followed by additional CFAE ablation.21,22,24,25,30 Elayi et al.23 was the only study in which the patients randomized to a CFAE strategy underwent CFAE ablation first, followed by APVI. Patients randomized to a non-CFAE strategy were randomized to APVI alone or CPVA alone.23 For this analysis, both the CPVA and APVI groups were combined for comparison with the group that underwent CFAE ablation followed by APVI. Two trials randomized patients to one of three treatment groups: Di Biase et al.22 randomized patients to APVI alone, CFAE ablation alone, or APVI followed by CFAE ablation; and the Substrate and Trigger Ablation for Reduction of AF (STAR-AF) trial, published by Verma et al.,25 randomized patients to CPVA alone, CFAE ablation alone, or CPVA followed by CFAE ablation. As treatment efficacy of stand-alone CFAE ablation was not the focus of this analysis, for both studies we excluded the group that received CFAE ablation alone.

Baseline patient characteristics

Of the 538 patients included in this meta-analysis, 270 (50.3%) had paroxysmal AF and 267 (49.7%) had persistent AF (AF classification was not reported for 1 patient). Overall, baseline patient characteristics between patients who underwent PVI alone compared with those who underwent PVI + CFAE were not significantly different (Table 3). Patients’ mean age across all trials was 57.9 ± 9.8 years and over three-fourths were male (76.0%). Across the five studies reporting the mean duration of AF, it was 6.1 ± 5.0 years. The mean left atrial diameter was 44.4 ± 5.7 mm and the mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 55.7 ± 8.8.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in RCTs

| Study | Patients (n) |

Mean age (years ± SD) |

Males [n (%)] |

Duration of AF (years ± SD) |

LA diameter (mm ± SD) |

LVEF (% ± SD) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | |

| Deisenhofer et al.21 | 48 | 50 | 58 ± 10 | 55 ± 10 | 33 (69) | 41 (82) | NRa | NRa | 43 ± 6 | 44 ± 5 | NR | NR |

| Di Biase et al.22 | 35 | 34 | 57 ± 8.1 | 58.4 ± 7.5 | 29 (83) | 30 (80) | 5.3 ± 5.7 | 5.3 ± 5 | 43 ± 0.6 | 44 ± 0.6 | 55 ± 8 | 54.6 ± 6 |

| Elayi et al.23 | 95 | 49 | 59 ± 10.2 | 59.2 ± 11.5 | 63 (66) | 32 (65) | 6.1 ± 3.4 | 6.3 ± 2.5 | 45 ± 6.9 | 46.2 ± 6.4 | 54 | 55 |

| Oral et al.30 | 30 | 30 | 55 ± 11 | 56 ± 9 | 24 (80) | 26 (87) | 7 ± 5 | 6 ± 4 | 43 ± 7 | 44 ± 6 | 59 ± 4 | 58 ± 7 |

| Oral et al.24 | 50 | 50 | 58 ± 10 | 62 ± 8 | 41 (82) | 41 (82) | 6 ± 5 | 5 ± 4 | 47 ± 6 | 46 ± 6 | 53 ± 12 | 54 ± 9 |

| Verma et al.25 | 32 | 34 | 55 ± 11 | 59 ± 10 | 24 (75) | 25 (74) | 6.4 ± 6.6 | 7.6 ± 9.4 | 43 ± 5 | 41 ± 6 | 62 ± 7 | 59 ± 12 |

| Total | 291 | 247 | 57.6 ± 10.1 | 58.4 ± 9.5 | 214 (74) | 195 (79) | 6.1 ± 4.8 | 6.0 ± 5.3 | 44.3 ± 6.0 | 44.4 ± 5.5 | 55.6 ± 10.0 | 55.8 ± 10.1 |

| P-value | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.82 | |||||||

NR, not reported.

aReported as 38 ± 31 h compared with 36 ± 33 h on pre-procedural Holter monitor in the PVI group.

Catheter ablation techniques and complex fractionated atrial electrogram definitions

The catheter ablation techniques and ablation endpoints varied among the six studies (Table 4). For each study, the control groups underwent stand-alone PVI—APVI in two studies,22,24 segmental PVI in one,21 CPVA in two studies,25,30 and either CPVA or APVI in one.23 All studies used RF energy and five used electroanatomical mapping with CARTO (Biosense Webster Inc., Diamond Bar, CA, USA),21–24,30 whereas one used Ensite NavX (St Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA).25 Maximum energy outputs and target temperatures during RF energy delivery differed for each study.

Table 4.

Catheter ablation techniques and CFAE definitions

| Study | Ablation techniques | Energy source | Catheter tip size (mm) |

Maximum energy output (W) |

Maximum temperature (°C) |

Definition of CFAE | Ablation endpoint | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | |||||

| Deisenhofer et al.21 | Segmental PVI; APVI + CFAE | RF | NR | NR | 30 | 35 | 43 | 43 | (i) Atrial EGMs that have fractionated EGMs composed of ≥2 deflections, and/or perturbation of the baseline with continuous deflection of a prolonged activation complex over a 10s recording period; or (ii) atrial EGMs with a very short cycle length (≤120 ms) averaged over a 10 s recording period | PVI: electrical isolation of all PVs |

| CFAE: termination to sinus rhythm with subsequent non-inducibility using high-frequency burst pacing × 5 | ||||||||||

| Di Biase et al.22 | APVI; CFAE; APVI + CFAE | RF | 3.5 | 3.5 | 45 | 45 | <41 | <41 | (i) Atrial EGMs with ≥2 deflections or with fractionated baseline complexes with continuous activity over a 10 s recording time; or (ii) atrial EGMs with a cycle length ≤120 ms over a 10 s recording time | PVI: local elimination of all PV potentials along antra or inside veins (entry and exit block) |

| CFAE: complete elimination of CFAE areas and electrical isolation of all PV antra defined by entrance and exit block | ||||||||||

| Elayi et al.23 | CPVA; APVI; CFAE + APVI | RF | 3.5 | 3.5 | 50 | 50 | 41 | 41 | (i) Atrial EGMs with fractionation and composed of ≥2 deflections and/or with continuous activity of the baseline; or (ii) atrial EGMs with cycle length ≤120 ms | PVI: elimination of all PV potentials along antra or inside veins (entry block) |

| CFAE: complete elimination of CFAEs | ||||||||||

| Oral et al.30 | CPVA; CPVA + CFAE | RF | 8 | 8 | 70 | 70 | 55 | 55 | Not described | AF termination with non-inducibility with atrial burst pacing × 5 at the shortest cycle length resulting in 1:1 atrial capture for ≥ 15 sa |

| Oral et al.24 | APVI; APVI + CFAE | RF | 3.5 | 3.5 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 45 | (i) Atrial EGMs with a cycle length ≤120 ms or shorter than the AF cycle length in the coronary sinus; or (ii) EGMs that were fractionated or displayed continuous electrical activity | PVI: complete electrical isolation of all PVs |

| CFAE: complete electrical isolation of all PVs with additional CFAE ablation in the LA and CS for up to 2 additional hours or until AF terminated, whichever came first | ||||||||||

| Verma et al.25 | CPVA; CFAE; CPVA + CFAE | RF | 3.5 or 8 | 3.5 or 8 | 60 | 60 | 50 | 50 | CFAE sites defined by automated algorithm (CL <120 ms) (Ensite NavX, St Jude Medical) | PVI: abolishment of all PV potentials within each antrum |

| CFAE: complete electrical isolation of all PVs followed by CFAE ablation if spontaneous or inducible AF | ||||||||||

CS, coronary sinus; EGM, electrogram; LA, left atrium; PV, pulmonary vein; RF, radiofrequency.

aThe endpoint of ablation was not defined separately for those patients who underwent additional CFAE ablation.

All but one study outlined the investigators’ definition of a CFAE to be targeted for ablation (Table 4).30 For four of the five studies that defined CFAEs, definitions were based on Nademanee et al.'s12 description: atrial electrograms with (i) fractionation composed of two or more deflections or continuous electrical activity over a 10 s period; or (ii) cycle length ≤120 ms over a 10 s period. Verma et al.25 used an automated algorithm (Ensite NavX, St Jude Medical) to define CFAE sites with cycle lengths <120 ms and Elayi et al.23 used automated algorithms from either CARTO or NavX.

Efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation + adjunctive complex fractionated atrial electrogram ablation

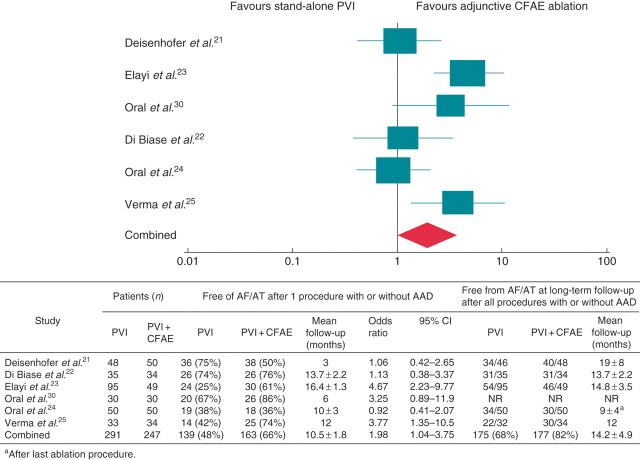

Random-effects modelling was used to assess the efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation compared with stand-alone PVI. For the primary endpoint of freedom from any AF/AT at ≥3 months of follow-up following a single ablation with or without AAD therapy, adjunctive CFAE ablation improved the odds of maintaining sinus rhythm compared with PVI alone (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.04–3.8, P = 0.04) (Figure 2). However, there was moderate heterogeneity among the six RCTs (I2 = 63.0%). Across all studies, the rate of repeat ablation was 25% among patients who underwent PVI alone and 21% among those who received adjunctive CFAE ablation (P = 0.27).

Figure 2.

Freedom from AF/AT at post-procedure follow-up. Odds ratios for PVI vs. PVI + CFAE.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation vs. persistent atrial fibrillation

To evaluate possible sources of the moderate heterogeneity among the combined RCTs, we performed separate sensitivity analyses based on AF classification: paroxysmal vs. persistent. Combining the three trials enrolling patients with paroxysmal AF, heterogeneity was markedly diminished (I2 = 6.2%); however, in this patient subgroup, adjunctive CFAE ablation did not demonstrate a significant treatment effect (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.74–2.7, P = 0.30). Between the two trials that enrolled patients with long-standing persistent AF, heterogeneity remained high (I2 = 88.2%) and again there was no evident treatment effect of adjunctive CFAE ablation among this patient subgroup (OR 2.1, 95% CI 0.42–10.3, P = 0.36). The results of the most recently published STAR-AF trial could not be included in sensitivity analyses as the primary endpoint data were not separately available for patients with paroxysmal vs. persistent AF.

Influence of individual trials

In order to assess the impact of individual studies on the overall treatment effect, we conducted serial sensitivity analyses in which each of the six RCTs was excluded in turn. The overall treatment effect with the serial exclusion of Oral et al.,24 Deisenhofer et al.,21 and Di Biase et al.22 each resulted in statistically significant increased odds of freedom from AF after a single procedure with or without AADs (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.22–4.60, P = 0.01; OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.09–4.65, P = 0.03; and OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.05–4.54, P = 0.04, respectively). Serial exclusion of Elayi et al.,23 Oral et al.,30 or Verma et al.25 led to similar OR and associations, but without statistical significance (OR 1.56, 95% CI 0.87–2.79, P = 0.14; OR 1.83, 95% CI 0.88–3.79, P = 0.10; and OR 1.75, 95% CI 0.84–3.75, P = 0.13, respectively).

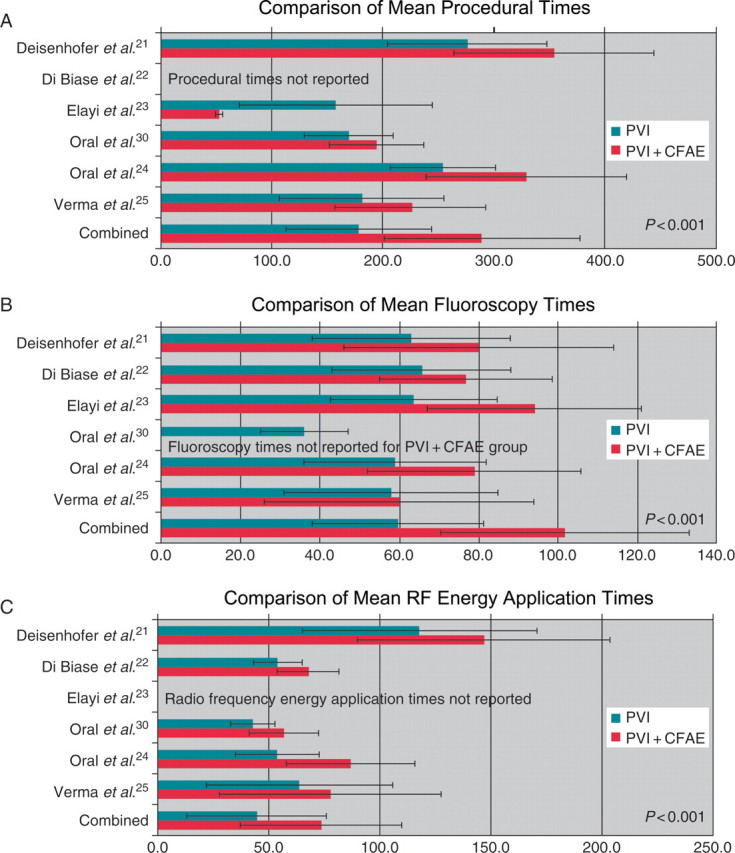

Secondary endpoints

Performing CFAE ablation significantly increased mean procedural times (178.5 ± 66.9 vs. 331.5 ± 92.6 min, P< 0.001), mean fluoroscopy (59.5 ± 22.2 vs. 115.5 ± 35.3 min, P< 0.001), and mean RF energy application times (46.9 ± 36.6 vs. 74.4 ± 43.0 min, P< 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF energy application times. Comparison of PVI vs. PVI + CFAE.

Pulmonary vein isolation + CFAE ablation organized AF into AT during the ablation in 32% of the patients across the five trials that reported this information, and of these patients, 40% were successfully converted to sinus rhythm by additional catheter ablation targeting these ATs. Reporting was asymmetric and incomplete for patients who underwent PVI alone; however, among the two trials that did report these numbers, 27% of the patients organized AF into AT and 40% of these patients were successfully converted to sinus rhythm after additional ablation targeting the resultant ATs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes of RCTs

| Study | Patients (n) |

No. of patients with post-procedure AT |

Repeat procedure for AF |

No. of patients with AF organization to AT |

No. of patients with AF termination to SR |

Persistence of AF requiring DCCV or ibutilide |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | PVI | PVI + CFAE | |

| Deisenhofer et al.21 | 48 | 50 | NR | 2/30 (7%) | 15/46a (33%) | 17/48a (35%) | NR | 10/30 (33%) | NR | 17/30 (57%) | NR | 3/30 (10%) |

| Di Biase et al.22 | 35 | 34 | NR | NR | 4/35 (11%) | 3/34 (9%) | 12/35 (34%) | 10/34 (29%) | 21/35 (60%) | 22/34 (65%) | 2/35 (6%) | 2/34 (6%) |

| Elayi et al.23 | 95 | 49 | NR | NR | 26/95 (27%) | 10/49 (20%) | 23/95 (24%) | 34/49 (70%) | 4/95 (4%) | 2/49 (4%) | 68/95 (72%) | 13/49 (27%) |

| Oral et al.30 | 30 | 30 | NR | 8/30 (27%) | 0/30 (0%) | 0/30 (0%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Oral et al.24 | 50 | 50 | 2/50 (4%) | 6/50 (12%) | 18/50 (36%) | 17/50 (34%) | NR | 4/50 (8%) | NR | 5/50 (10%) | NR | 45/50 (90%) |

| Verma et al.25 | 32 | 34 | NR | NR | 10/33 (31%) | 5/34 (15%) | NR | 8/34 | 26/33 | 11/34 | 6/33 | 7/34 |

| Total | 291 | 247 | 2/50 (4%) | 16/110 (15%) | 73/289 (25%) | 52/245 (21%) | 35/130 (27%) | 66/197 (34%) | 51/163 (31%) | 46/197 (29%) | 76/163 (47%) | 70/197 (36%) |

NR, not reported.

aTwo patients from each treatment group lost during long-term follow-up.

The risk of recurrence of organized ATs post-procedure was not consistently reported. One study reported rates for both treatment arms: 4% in the stand-alone PVI group and 12% in the PVI + CFAE group.24 In this study, one patient in the stand-alone PVI and three patients in the PVI + CFAE group underwent a separate ablation to target clinically significant AT (one patient in the PVI + CFAE group subsequently underwent a third ablation for recurrent AT after the second procedure).24 Two other studies reported the rate of post-procedure ATs in the PVI + CFAE groups only (27% in Oral et al.24 and 7% in Deisenhofer et al.21), but did not report whether subsequent ATs developed in the PVI only groups.

Complications

For most of these studies, complications were reported in aggregate from both initial and repeat procedures. There were very few procedural complications overall (n= 18/538 patients, 3.3%) among the five studies for which complications were reported.21–25 The most common complication was bleeding or vascular complications (n= 6), followed by pericardial effusion (n= 5), of which one was due to cardiac perforation with tamponade, and at least three of these patients had undergone PVI + CFAE. Although one study reported 5 of the 18 total reported complications (1 pericardial effusion, 2 pericarditis, and 2 bleeding/vascular complications), this study did not specify whether the patients were in the PVI group vs. the PVI + CFAE group.24 Pulmonary vein stenosis was reported in three patients who received PVI alone and one patient who received PVI + CFAE. None of the studies reported deaths related to the catheter ablation procedures. One patient who underwent PVI + CFAE survived a prolonged asystolic arrest that occurred 3 h post-procedure during venous sheath removal.21 Overall, the small numbers of complications (4 with PVI vs. 9 with PVI + CFAE) precluded further analysis of the relative risk of complication with one ablation strategy vs. the other given the available data.

Discussion

There are three main findings of this meta-analysis. First, the efficacy of CFAE ablation in addition to PVI for the maintenance of sinus rhythm after a single procedure with or without AADs is 66%, which is significantly improved compared with PVI alone. Second, procedural complications are minimal; however, adjunctive CFAE ablation is associated with increased procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF energy application times. Third, sensitivity analyses suggest that differences in ablation technique, patient selection, and other variables may be important determinants of outcome after adjunctive CFAE ablation and additional studies are still needed to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of adjunctive CFAE ablation for the maintenance of sinus rhythm.

The strategy of adjunctive CFAE ablation continues to evolve and there are a variety of factors that likely impact the identification of CFAEs and the potential for procedural efficacy when they are targeted for ablation. First, in the earlier five of the six RCTs analysed, CFAEs were identified by real-time visual inspection, which can be challenging and subject to inter-observer variability.31 With the increasing utilization of automated CFAE detection algorithms, CFAEs will become more reliably and objectively identified and targeted.32 However, the optimal criteria for the detection of CFAEs has yet to be determined.31 Secondly, the five RCTs performed before the most recently published STAR-AF trial limited CFAE ablation to the left atrium. The role of right atrial CFAEs remains incompletely elucidated, and thus, the clinical efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation may improve with biatrial CFAE ablation. Thirdly, understanding of both the genesis and clinical significance of CFAEs in different patient subgroups is unclear.33 Theoretically, CFAEs could be produced by multiple mechanisms and could thus represent a multitude of electroanatomic substrates not all of which are necessarily relevant to AF elimination.34 As such, it is possible that different CFAE subtypes exist and that techniques to identify and target CFAEs together with patient selection criteria will impact the efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation.

Safety considerations

Evaluation of the therapeutic value of a treatment strategy should include consideration of the risk–benefit relationship. These studies suggest that the strategy of CFAE ablation in addition to PVI results in lengthened procedural and fluoroscopy times, which could theoretically increase anaesthesia-related complications and would be expected to increase exposure to ionizing radiation.35,36 In this analysis, we found a nearly 50% increase in ionizing radiation burden with adjunctive CFAE ablation compared with PVI alone. In light of known associations between increased exposure to ionizing radiation and the development of solid tumours, leukaemia, and even cardiovascular disease,37,38 this procedural risk may be real, though warranted, if procedural efficacy is significantly improved. Adjunctive CFAE ablation also lengthens RF energy application time, which could potentially increase the risk of developing a pericardial effusion; however, given the small number of complications in these RCTs, there are not yet enough data available to make any conclusions. Furthermore, additional non-linear ablation could result in a greater propensity for atrial proarrhythmia. On the basis of these data, it is possible that CFAE ablation is proarrhythmic. Recurrent post-procedure AT was 4% with PVI vs. 15% with PVI + CFAE; however, adequately powered trials are still needed to answer this question. To optimally balance procedural risk and benefit, more data on complications and longer-term follow-up, as well as ablation methods and patient selection, are necessary.

Limitations

As with any meta-analysis, the possibility of publication bias cannot be excluded. Likewise, the inclusion of RCTs performed at high-volume centres with experienced operators may not reflect the experience of patients treated in general clinical practice, particularly given the complex nature of CFAE identification and ablation. Our findings were sensitive to the inclusion of several trials, likely reflecting the relatively small sample size, different patient populations, varying ablation techniques, and/or modest treatment effect. These studies’ relatively short and highly variable follow-up times, different ablation endpoints, wide variation in post-procedure AAD use and reporting, and differences in the primary endpoints further limited our analysis. Procedural efficacy after a single procedure may also disproportionately reflect an inability to achieve permanent isolation of the pulmonary veins rather than a lack of benefit from CFAE ablation, thus underestimating the efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation. Furthermore, with the exception of the STAR-AF trial, patients who received repeat/multiple procedures did not follow the initial randomization assignment regarding ablation strategy. Owing to the relatively small sample sizes of the available RCTs, studies with distinctly different AF populations (paroxysmal vs. long-standing persistent) and varying PVI techniques were combined. Pooling paroxysmal and persistent AF patients, who likely have different underlying substrates, may underestimate the efficacy of CFAE ablation in one or the other group. As only two RCTs have yet been published evaluating adjunctive CFAE ablation in persistent AF patients, more studies are clearly needed in this patient population for whom CFAE ablation may have more incremental benefit. Finally, as we did not have access to the original data from each of the trials, extrapolation errors and the combining of data from multiple control groups into one group through weighting may have affected our results. Without access to patient-level data, meta-analytical methods could not be used to identify predictors of ablation outcomes and AF recurrence.

Clinical implications

With the ever-increasing prevalence of AF combined with the limited efficacy of AADs, PVI has become a commonly performed RF catheter ablation procedure. The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommend catheter ablation as second-line therapy once a patient has failed one or more AADs (Class IIb).39 Strategies to improve the efficacy of AF ablation continue to evolve, such as the adjunctive ablation of CFAEs, which improves the maintenance of sinus rhythm after a single procedure compared with PVI alone. Although there may be increased risk associated with the increased procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF energy application times, additional studies are still needed to fully evaluate the risk–benefit profile of adjunctive CFAE ablation. Future randomized studies comparing stand-alone PVI to adjunctive CFAE ablation may provide additional information about clinical efficacy in the absence of AADs, and in specific subpopulations like persistent AF patients, as well as include longer-term follow-up to define the durability of treatment effect, and further elucidate the efficacy and safety profile of CFAE ablation.

Conclusions

The efficacy of adjunctive CFAE ablation is improved compared with stand-alone PVI for the maintenance of sinus rhythm after a single catheter ablation with or without AADs. The improved efficacy of PVI with adjunctive CFAE ablation should be weighed against possible added risk due to significantly increased procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF energy application times.

Conflict of interest: M.H.K. receives research funding from Biotronik and serves on an advisory board for Medtronic. J.P.P. receives research funding from Boston Scientific and serves on an advisory board for Medtronic. T.D.B. receives research funding from Medtronic, St Jude Medical, and Biosense Webster, Inc.; and participates as a consultant and/or speaker for Sequel Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis, Hansen Medical, and Philips Medical Systems.

Funding

M.H.K. was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein-National Research Service Award (Kirschstein-NRSA) National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number 5-T32-DK-007731-15). The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Gjesdal K, Vist GE, Bugge E, Rossvoll O, Johansen M, Norderhaug I, et al. Curative ablation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2008;42:3–8. doi: 10.1080/14017430701798838. doi:10.1080/14017430701798838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair GM, Nery PB, Diwakaramenon S, Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Morillo CA. A systematic review of randomized trials comparing radiofrequency ablation with antiarrhythmic medications in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:138–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01285.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noheria A, Kumar A, Wylie JV, Jr, Josephson ME. Catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:581–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.581. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piccini JP, Lopes RD, Kong MH, Hasselblad V, Jackson K, Al-Khatib SM. Pulmonary vein isolation for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:626–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.856633. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.856633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jais P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, Daoud E, Khairy P, Subbiah R, et al. Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study. Circulation. 2008;118:2498–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772582. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krittayaphong R, Raungrattanaamporn O, Bhuripanyo K, Sriratanasathavorn C, Pooranawattanakul S, Punlee K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of radiofrequency catheter ablation and amiodarone in the treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86:S8–16. Suppl. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oral H, Pappone C, Chugh A, Good E, Bogun F, Pelosi F, Jr, et al. Circumferential pulmonary-vein ablation for chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:934–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050955. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappone C, Augello G, Sala S, Gugliotta F, Vicedomini G, Gulletta S, et al. A randomized trial of circumferential pulmonary vein ablation versus antiarrhythmic drug therapy in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the APAF Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.037. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stabile G, Bertaglia E, Senatore G, De Simone A, Zoppo F, Donnici G, et al. Catheter ablation treatment in patients with drug-refractory atrial fibrillation: a prospective, multi-centre, randomized, controlled study (Catheter Ablation For The Cure Of Atrial Fibrillation Study) Eur Heart J. 2006;27:216–21. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi583. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, Verma A, Bhargava M, Saliba W, et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2634–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2634. doi:10.1001/jama.293.21.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arruda M, Natale A. Ablation of permanent AF: adjunctive strategies to pulmonary veins isolation: targeting AF NEST in sinus rhythm and CFAE in AF. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2008;23:51–7. doi: 10.1007/s10840-008-9252-z. doi:10.1007/s10840-008-9252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, Schwab M, Sunsaneewitayakul B, Vasavakul T, et al. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2044–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oral H, Chugh A, Good E, Wimmer A, Dey S, Gadeela N, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of chronic atrial fibrillation guided by complex electrograms. Circulation. 2007;115:2606–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691386. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nademanee K, Schwab MC, Kosar EM, Karwecki M, Moran MD, Visessook N, et al. Clinical outcomes of catheter substrate ablation for high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:843–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.044. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haissaguerre M, Sanders P, Hocini M, Takahashi Y, Rotter M, Sacher F, et al. Catheter ablation of long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation: critical structures for termination. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1125–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00307.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma A, Novak P, Macle L, Whaley B, Beardsall M, Wulffhart Z, et al. A prospective, multicenter evaluation of ablating complex fractionated electrograms (CFEs) during atrial fibrillation (AF) identified by an automated mapping algorithm: acute effects on AF and efficacy as an adjuvant strategy. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.027. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter M, Spear W, Akar JG, Helms R, Brysiewicz N, Santucci P, et al. Prospective study of atrial fibrillation termination during ablation guided by automated detection of fractionated electrograms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:613–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01189.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin YJ, Tai CT, Chang SL, Lo LW, Tuan TC, Wongcharoen W, et al. Efficacy of additional ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms for catheter ablation of nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:607–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01393.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estner HL, Hessling G, Ndrepepa G, Luik A, Schmitt C, Konietzko A, et al. Acute effects and long-term outcome of pulmonary vein isolation in combination with electrogram-guided substrate ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.053. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt C, Estner H, Hecher B, Luik A, Kolb C, Karch M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE): preferential sites of acute termination and regularization in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1039–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00930.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deisenhofer I, Estner H, Reents T, Fichtner S, Bauer A, Wu J, et al. Does electrogram guided substrate ablation add to the success of pulmonary vein isolation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation? A prospective, randomized study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:514–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01379.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Biase L, Elayi CS, Fahmy TS, Martin DO, Ching CK, Barrett C, et al. Atrial fibrillation ablation strategies for paroxysmal patients: randomized comparison between different techniques. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:113–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.798447. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.798447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elayi CS, Verma A, Di Biase L, Ching CK, Patel D, Barrett C, et al. Ablation for longstanding permanent atrial fibrillation: results from a randomized study comparing three different strategies. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.016. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oral H, Chugh A, Yoshida K, Sarrazin JF, Kuhne M, Crawford T, et al. A randomized assessment of the incremental role of ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms after antral pulmonary vein isolation for long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:782–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.054. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma A, Mantovan R, Macle L, De Martino G, Chen J, Morillo CA, et al. Substrate and Trigger Ablation for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation (STAR AF): a randomized, multicentre, international trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1344–56. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq041. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC, et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2803–17. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm358. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, Cappato R, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert Consensus Statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:816–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khaykin Y, Skanes A, Champagne J, Themistoclakis S, Gula L, Rossillo A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of electroanatomic circumferential pulmonary vein ablation supplemented by ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms versus potential-guided pulmonary vein antrum isolation guided by intracardiac ultrasound. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:481–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.848978. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.848978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oral H, Chugh A, Lemola K, Cheung P, Hall B, Good E, et al. Noninducibility of atrial fibrillation as an end point of left atrial circumferential ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized study. Circulation. 2004;110:2797–801. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146786.87037.26. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000146786.87037.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ndrepepa G. Standardization of criteria used in automated algorithms for detection of fractionated electrograms to guide substrate-based ablation of atrial fibrillation: no rest for the wicked. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1142–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aizer A, Holmes DS, Garlitski AC, Bernstein NE, Smyth-Melsky JM, Ferrick AM, et al. Standardization and validation of an automated algorithm to identify fractionation as a guide for atrial fibrillation ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.04.021. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park JH, Pak HN, Kim SK, Jang JK, Choi JI, Lim HE, et al. Electrophysiologic characteristics of complex fractionated atrial electrograms in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:266–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01321.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rostock T, Rotter M, Sanders P, Takahashi Y, Jais P, Hocini M, et al. High-density activation mapping of fractionated electrograms in the atria of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.019. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Ross JS, Chen J, Ting HH, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:849–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901249. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0901249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nademanee K, Oketani N. The role of complex fractionated atrial electrograms in atrial fibrillation ablation moving to the beat of a different drum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:790–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.022. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Research Council. Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little MP, Tawn EJ, Tzoulaki I, Wakeford R, Hildebrandt G, Paris F, et al. Review and meta-analysis of epidemiological associations between low/moderate doses of ionizing radiation and circulatory disease risks, and their possible mechanisms. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2010;49:139–53. doi: 10.1007/s00411-009-0250-z. doi:10.1007/s00411-009-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]