Abstract

Cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in the pathology of myocardial infarction. The protective effects of caffeic acid on mitochondrial dysfunction in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction were studied in Wistar rats. Rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) for 10 days. After the pretreatment period, isoproterenol (100 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected to rats at an interval of 24 h for 2 days to induce myocardial infarction. Isoproterenol-induced rats showed considerable increased levels of serum troponins and heart mitochondrial lipid peroxidation products and considerable decreased glutathione peroxidase and reduced glutathione. Also, considerably decreased activities of isocitrate, succinate, malate, α-ketoglutarate, and NADH dehydrogenases and cytochrome-C-oxidase were observed in the mitochondria of myocardial-infarcted rats. The mitochondrial calcium, cholesterol, free fatty acids, and triglycerides were considerably increased and adenosine triphosphate and phospholipids were considerably decreased in isoproterenol-induced rats. Caffeic acid pretreatment showed considerable protective effects on all the biochemical parameters studied. Myocardial infarct size was much reduced in caffeic acid pretreated isoproterenol-induced rats. Transmission electron microscopic findings also confirmed the protective effects of caffeic acid. The possible mechanisms of caffeic acid on cardiac mitochondria protection might be due to decreasing free radicals, increasing multienzyme activities, reduced glutathione, and adenosine triphosphate levels and maintaining lipids and calcium. In vitro studies also confirmed the free-radical-scavenging activity of caffeic acid. Thus, caffeic acid protected rat’s heart mitochondria against isoproterenol-induced damage. This study may have a significant impact on myocardial-infarcted patients.

Keywords: Caffeic acid, Isoproterenol, Mitochondrial enzymes, Lipids, Transmission electron microscopy

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) continues to be a major public health problem, not only in Western countries but also increasingly in developing countries and it makes a significant contribution to the mortality statistics (Sabeena Farvin et al. 2004; Gilski and Borkenhagen 2005). MI is the acute condition of necrosis of the myocardium that occurs as a result of imbalance between coronary blood supply and myocardial demand (De Bono and Boon 1992). Isoproterenol (ISO), a β-adrenergic agonist causes oxidative stress in the myocardium resulting in gross and microscopic infarct in rat’s heart muscle (Wexler and Greenberg 1978). It has been reported that ISO produces free radicals and stimulates lipid peroxidation, which is a causative factor for irreversible damage to the myocardial membrane (Sushama Kumari et al. 1989). The biochemical mechanism of cell injury and death of the myocardial cell after MI remains unresolved. By studying the biochemical alterations that take place in an animal model, it is possible to gain more insight into the mechanisms leading to the altered metabolic process in human MI.

Dietary factors play a vital role in the development of various human diseases including cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Recently, there has been an upsurge of interest to explore the cardioprotective potential of natural products (Karthikeyan et al. 2007). Natural products have lesser side effects than synthetic drugs. Phenolic acids have received much attention because of their role in the prevention of many human diseases, particularly atherosclerosis and cancer due to their antioxidant properties (Mattila and Kumpulainen 2002). Hydroxy cinnamic acids are the major classes of phenolic compounds, which are found in almost every plant (Herrmann 1976). The most representative of hydroxy cinnamic acids is caffeic acid (CA). Caffeic acid (3, 4-dihydroxy cinnamic acid) is one of the most common phenolic acids which occur in fruits, grains, and dietary supplements (Castellari et al. 2002). The intake of CA from foods mainly from tomatoes and potatoes was estimated to be about 0.2 mg/kg body weight per day (National Research Council 1996). Furthermore, CA exhibits multipharmacological effects such as antioxidant (Kono et al. 1997), free radical scavenging (Gulcin 2006), and chelator of metal ions (Psotova et al. 2003). A previous scientific report has revealed that CA inhibits oxidation of low-density lipoprotein in vitro and might therefore protect against CVD (Nardini et al. 1995).

Mitochondria are important subcellular organelles for cellular oxidative process and are also the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cell. They are called as power house of the cell because they carry out a vital biochemical process called oxidative phosphorylation. Mitochondria are the main source of energy, which sustain cellular metabolism and integrity. The decrease in oxygen supply during MI impairs energy production by mitochondria. Mitochondria are the location of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis for energy production and electron transport chain. Prolonged oxidative stress in failing myocardium results in damage to mitochondrial DNA, ROS generation, and consequent cellular injury leading to functional decline. Thus, mitochondria serve both as a source and target of ROS-mediated injury in failing heart. Defective mitochondrial function is a fundamental characteristic of the failing heart. ISO causes Ca2+ overload in myocardium (Chagoya de Sanchez et al. 1997), disruption of the mitochondria (Xia et al. 2002), inactivation of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzymes, alterations in mitochondrial respiration (Prabhu et al. 2006a, b), and depletion of ATP.

The viability of the myocardial cell depends for most part on the integrity of several membrane systems. The major source of energy for contraction comes from the oxidative metabolism of mitochondria in the myocardial cell. For this reason, the function of mitochondria in MI is of particular interest. Studies also suggesting that benefit may be derived from the development of therapies aimed at preserving cardiac mitochondrial function (Murray et al. 2007). There are very few scientific reports available on the effect of phenolic acids and their mechanism in MI. Though several studies have been performed aiming at preserving cardiac mitochondrial function, to our knowledge there is no scientific study available on CA correlating cardiac mitochondrial function in myocardial-infarcted rats. The mechanism(s) of cardioprotective effect of CA is not fully investigated. A detailed study is necessary to know whether CA plays any protective role in the cardiac mitochondrial damage in MI. Since mitochondrial damage plays a vital role in the pathology of MI, we undertook this study to evaluate the protective effects of CA on troponins-T and I, heart mitochondrial lipid peroxidation, antioxidants, TCA cycle and respiratory marker enzymes, lipids, Ca2+, and ATP in ISO-induced myocardial-infarcted rats. Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) assay on myocardial infarct size was also carried out to confirm the cardioprotective effects of CA. Furthermore, the protective effect of CA on the structure of heart mitochondria was studied by transmission electron microscopic (TEM) study. In addition to this, in vitro free-radical-scavenging effects on free radicals such as superoxide anion and hydroxyl radical were studied to know the underlying mechanism of CA.

Materials and methods

Drug and chemicals

Caffeic acid, isoproterenol hydrochloride, nitroblue tetrazolium, phenazine methosulfate, butylated hydroxy toluene, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitro benzene, 2,4-dinitro phenyl hydrazine, trisodium citrate, glutathione, potassium-α-ketoglutarate, thiamine pyrophosphate, sodium succinate, oxaloacetate, and cytochrome-C were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. All other chemicals and solvents used were of highest analytical grade.

Experimental animals

The whole experiment was done according to the guidelines of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals, New Delhi, India, and approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Annamalai University (approval no.556: 20.3.2008). The study was conducted on 40 male albino Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) weighing 170–200 g, obtained from the Central Animal House, Department of Experimental Medicine, Rajah Muthiah Institute of Health Sciences, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu, India. They were housed in polypropylene cages (47 × 34 × 20 cm; four rats per cage) lined with husk, renewed every 24 h under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle at around 22°C and had free access to tap water and food. The rats were fed on a standard pelleted diet (Pranav Agro Industries Limited, Maharashtra, India). The diet provided metabolizable energy of 3,600 kcal.

Induction of experimental myocardial infarction

Isoproterenol (100 mg/kg) dissolved in saline was subcutaneously injected to rats at an interval of 24 h for 2 days. ISO-induced MI was confirmed by elevated levels of serum creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB, and lactate dehydrogenase in rats.

Experimental design and dosage fixation

A dose-dependent study conducted with three different doses of CA (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) in ISO-induced rats showed significant effects on serum CK. But 15 mg/kg showed the highest significant (P < 0.05) effect than the other two doses (5 and 10 mg/kg). Hence, we have chosen only 15 mg/kg for our further study. Forty male albino Wistar rats were divided into four groups. Ten rats were used in each group. Two rats in each group were taken for TTC study and two rats in each group were taken for TEM study. Group I: normal control rats; Group II: normal rats were treated with CA (15 mg/kg); Group III: rats were subcutaneously injected with ISO (100 mg/kg) twice at an interval of 24 h (on 11th and12th day); and Group IV: rats were pretreated with CA (15 mg/kg) and then subcutaneously injected with ISO at an interval of 24 h for 2 days (on 11th and 12th day). CA was dissolved in 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and administered to rats orally using an intragastric tube daily for a period of 10 days. Normal control and ISO control rats received 0.5% DMSO alone. The dosage fixation and duration of CA was based on our dose-dependent study (Fig. 1).

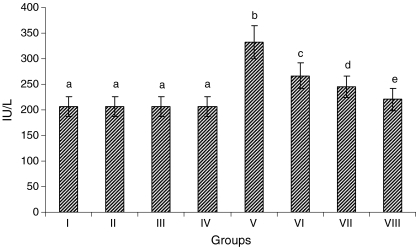

Fig. 1.

Activity of serum creatine kinase (dose-dependent study). Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (5 mg/kg), Group III rats were treated with caffeic acid (10 mg/kg), Group IV rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg /kg), Group V ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group VI rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (5 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg), Group VII rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (10 mg/kg) + ISO(100 mg/kg), Group VIII rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letters (a, b, c, d, e) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

At the end of the experimental period, after 12 h of second ISO injection (on 13th day), all the rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium and sacrificed by cervical decapitation. Blood was collected and serum separated for various biochemical estimations. The heart was dissected out immediately and stored for mitochondrial isolation.

Estimation of serum cardiac troponins (cTnT and cTnI) and creatine kinase

The levels of serum cTnT and cTnI were estimated by chemiluminescence immunoassay using standard kits (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). Serum CK activity was assayed by a commercial kit obtained from Agappe Diagnostics, Kerala, India.

Isolation of heart mitochondria

The mitochondrial fraction of the heart tissue was isolated by the standard method of Takasawa et al. (1993). The heart tissue was put into ice-cold 50 mM Tris–hydrochloric acid buffer (Tris–HCl; pH 7.4) containing 0.25 M sucrose and homogenized. The homogenates were centrifuged at 700×g for 20 min and then the supernatants obtained were centrifuged at 9,000×g for 15 min. Then, the pellets were washed with 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.25 M sucrose and finally resuspended in the same buffer.

Estimation of lipid peroxidation products, antioxidants, mitochondrial enzymes, adenosine triphosphate, and protein content in heart mitochondrial fraction

Estimation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

The concentration of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was estimated by the method of Fraga et al. (1988). One milliliter of the mitochondrial fraction was treated with 2.0 ml of thiobarbituric acid–trichloro aectic acid–hydrochloric acid reagent and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was kept in a boiling water bath for 15 min. After cooling, the tubes were centrifuged for 10 min and the supernatant was taken for measurement. The absorbance was read at 535 nm against the reagent blank.

Estimation of lipid hydroperoxide

The levels of lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction were estimated by the method of Jiang et al. (1992). Fox reagent, 1.8 ml, was mixed with 0.2 ml of the heart mitochondrial fraction and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The color developed was read at 560 nm.

Assay of glutathione peroxidase

The activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed by the method of Rotruck et al. (1973). To 0.2 ml of Tris buffer, 0.2 ml of ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), 0.1 ml of sodium azide, and 0.5 ml of mitochondrial fraction were added. To the mixture, 0.2 ml of glutathione followed by 0.1 ml of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was also added. The contents were mixed well and incubated at 37°C for 10 min along with a tube containing all the reagents except the sample. After 10 min, the reaction was arrested by the addition of 0.5 ml of 10% trichloro acetic acid (TCA), centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for the estimation of glutathione by the method of Ellman (1959).

Estimation of reduced glutathione

The level of glutathione (GSH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was estimated by the method of Ellman (1959). Mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml, was pipetted out and precipitated with 2.0 ml of 5% TCA. After centrifugation, 1.0 ml of the supernatant was taken and added 0.5 ml of Ellman’s reagent and 3.0 ml of phosphate buffer. The yellow color developed was read at 412 nm.

Assay of isocitrate dehydrogenase

The activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed in the heart mitochondria by the method of King (1965). The incubation mixture contained 0.4 ml of Tris-HCl buffer, 0.2 ml of substrate, 0.2 ml of manganese chloride, 0.2 ml of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), and 0.2 ml of mitochondrial fraction. The NADP+ was replaced by 0.2 ml of saline in tubes labeled as control. A suitable aliquot of enzyme preparation was added and mixed well. The tubes were then incubated at 37°C for 60 min. At the end of the incubation period, 1.0 ml of the coloring reagent and 0.5 ml of EDTA were added. The contents of the tubes were mixed well and allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min and 10 ml of 0.4 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added and the color intensity was read at 420 nm after 10 min in a UV-spectrophotometer.

Assay of succinate dehydrogenase

The activity of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed by the method of Slater and Borner (1952). The reaction mixture contained 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer, 0.1 ml of EDTA, 0.1 ml of sodium cyanide, 0.1 ml of bovine serum albumin, 0.3 ml of sodium succinate, 0.2 ml of potassium ferricyanide, and made up to 2.8 ml with distilled water. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.2 ml of mitochondrial fraction. The change in optical density was recorded at 15-s intervals for 5 min at 420 nm.

Assay of malate dehydrogenase

The activity of malate dehydrogenase (MDH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed by the method of Mehler et al. (1948). The reaction mixture contained 0.75 ml of phosphate buffer, 0.15 ml of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), and 0.75 ml of oxaloacetate. The reaction was done at 25°C and was started by the addition of 0.2 ml of mitochondrial fraction. The control tubes contained all reagents except NADH. The change in optical density at 340 nm was measured for 2 min at an interval of 15 s in a Systronics UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Assay of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase

The activity of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed by the method of Reed and Mukherjee (1969). The incubation mixture contained 0.1 ml of phosphate buffer, 0.1 ml of thiamine pyrophosphate, 0.1 ml of magnesium sulfate, 0.1 ml potassium α-ketoglutarate, and 0.1 ml of potassium ferricyanide and distilled water to a final volume of 1.4 ml. A suitable aliquot of the mitochondrial fraction was added in test, while it was replaced by distilled water in the control. The mixture was then incubated at 30°C for 30 min. At the end of this period, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1.0 ml of 10% TCA. The mitochondrial fraction was added to the control after TCA was added. The mitochondrial fraction was centrifuged. To this, 1.0 ml of supernatant, 1.0 ml of 10% TCA, 1.5 ml of distilled water, 1.0 ml of 4% duponol, and 0.5 ml of ferric ammonium sulfate–duponol reagent were added. Then, the tubes were allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min. The color intensity was measured at 540 nm in a spectrophotometer.

Assay of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase

The activity of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase (NADH dehydrogenase) in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed according to the method of Minakami et al. (1962). The reaction mixture contained 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer, 0.1 ml of potassium ferricyanide, 0.1 ml of NADH, and 0.2 ml of mitochondrial fraction. The total volume was made up to 3.0 ml with distilled water. NADH was added just before the addition of the mitochondrial fraction. A control was also treated similarly without NADH. The change in optical density was measured at 420 nm as a function of time for 3 min at an interval of 15 s in a Systronics UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Assay of cytochrome-C-oxidase

The activity of cytochrome-C-oxidase in the heart mitochondrial fraction was assayed by the method of Pearl et al. (1963). The reaction mixture contained 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer, 0.2 ml of 0.2% N-phenyl-p-phenylene diamine, 0.1 ml of 0.01% cytochrome-C, and 0.5 ml of distilled water. The mitochondrial fraction was incubated at 25°C for 5 min. Mitochondrial fraction, 0.2 ml, was added and change in optical density was recorded at 550 nm for 5 min at an interval of 15 s each. A control containing all the reagents except cytochrome-C was also processed in the similar manner.

Estimation of adenosine triphosphate

ATP concentration in the heart mitochondrial fraction was measured by the method of Williams and Coorkey (1967). The incubation mixture contained 2 ml of buffer (pH 7.4), 10 mM magnesium chloride, 5 mM EDTA, 10 μl of adenosine diphosphate, and 5 μl of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. It was mixed thoroughly and the fluorescence was recorded. Then 5 μl of hexokinase and 10 μl of ATP were added and the increase in fluorescence at 340 nm was recorded.

Estimation of calcium

The level of Ca2+ ion in the heart mitochondrial fraction was measured by the O-Cresolphthalein complexone method by a reagent kit purchased from Span Diagnostic Limited, India.

Estimation of protein in the heart mitochondrial fraction

Protein content in the mitochondrial fraction was estimated by the method of Lowry et al. (1951). Mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml, was precipitated with 0.5 ml of 10% TCA, centrifuged for 10 min, and the precipitate was dissolved in 1.0 ml of 0.1 N NaOH. Aliquot, 0.1 ml, was taken and made up to 1.0 ml with distilled water. Then, 4.5 ml of alkaline copper reagent was added and allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. After incubation, 0.5 ml of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent was added and the blue color developed was read at 620 nm after 20 min.

Extraction of lipids and estimation of cholesterol, free fatty acids, triglycerides, and phospholipids in the heart mitochondrial fraction

Extraction of lipids

Lipids were extracted from the heart mitochondrial fraction by the method of Folch et al. (1957).

Estimation of total cholesterol

The levels of total cholesterol were estimated by the method of Zlatkis et al. (1953). Of the mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml was evaporated to dryness. To this, 5.0 ml of ferric chloride–acetic acid reagent was added. After mixing well, 3.0 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was added and the absorbance was read at 560 nm after 20 min. A series of standards containing cholesterol in the range of 3–15 μg were made to 5.0 ml with the reagent and a blank containing 5.0 ml of the reagent was prepared.

Estimation of free fatty acids

Free fatty acids (FFAs) levels were estimated by the method of Falholt et al. (1973). Of the mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml was evaporated to dryness. To this, accurately 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer, 6.0 ml of extraction solvent, and 2.5 ml of copper reagent were added. All the tubes were shaken vigorously for 90 s and were kept aside for 15 min. Then, the tubes were centrifuged and 3.0 ml of the upper layer was transferred to another tube containing 0.5 ml diphenyl carbazide solution and mixed carefully. The absorbance was read at 550 nm after 15 min. One milliliter of phosphate buffer was treated as blank.

Estimation of triglycerides

Triglycerides (TGs) levels were estimated by the method of Fossati and Prencipe (1982). Of the mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml was evaporated to dryness. To this, 0.1 ml of methanol was added followed by 4.0 ml of isopropanol. About 0.4 g of alumina was added to all the tubes and shaken well for 15 min. It was centrifuged and 2.0 ml of the supernatant was transferred to appropriately labeled tubes. The tubes were placed in a water bath at 65°C for 15 min for saponification after adding 0.6 ml of the saponification reagent followed by 0.5 ml of acetyl acetone reagent. After mixing, the tubes were kept in a water bath at 65°C for an hour. A series of standards of concentration 8–40 μg triolein were treated similarly along with a blank containing only the reagents. All the tubes were cooled and read at 405 nm.

Estimation of phospholipids

Phospholipids (PLs) levels were estimated by the method of Zilversmit and Davis (1950). Of the mitochondrial fraction, 0.5 ml was pipetted into a Kjeldahl flask and evaporated to dryness. One milliliter of 5 N H2SO4 was added and digested in a digestion rack till the appearance of light brown color. Two to three drops of concentrated nitric acid was added and the digestion continued till it became colorless. The Kjeldahl flask was cooled and 1.0 ml of distilled water was added and heated in a boiling water bath for about 5 min. Then, 1.0 ml of 2.5% ammonium molybdate and 0.1 ml of 1-amino-2-naphthol-4-sulphonic acid were added. The volume was then made up to 5.0 ml with distilled water and the absorbance was measured at 660 nm within 10 min.

TTC assay

A section of the heart tissue was used for the TTC assay. The macroscopic enzyme-mapping assay (TTC test) of the infarcted myocardium was done according to the method of Lie et al. (1975). A freshly prepared solution of 1% TTC in phosphate buffer was prewarmed at 37–40°C for 30 min in a darkened glass. To remove excess blood, the heart tissues were washed rapidly in cold water without macerating the tissue. After removing epicardial fat, the left ventricle was taken separately. The heart was transversely cut across the left ventricle to obtain slices not more than 0.1–0.2 mm in thickness. Then, the heart tissue slices were kept in the covered, darkened glass dish containing prewarmed solution of TTC and the dish was kept in an incubator and heated to 37–40°C for 45 min. The heart slices were turned over thrice and made certain that it remains completely immersed in the TTC solution. At the end of the incubation period, the heart slices were kept in fixing solution to fix the tissue. A camera with macrolens was used to take color photographs of heart slices. The expected reaction of the TTC test was as follows: normal myocardium (LDH enzyme active) turned to bright red, ischemic myocardium (LDH enzyme deficient) turned to pale gray or uncolored and fibrous scars turned to white.

TEM study

Small pieces of heart were taken and rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). Approximately, 1 mm heart pieces were trimmed and immediately fixed into 3% ice-cold glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and kept at 4°C for 12 h. Then, tissue processing for TEM study was carried out. The grids containing sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 0.2% lead acetate. Then, the sections were examined under a TEM (×20,000).

In vitro studies

Superoxide anion scavenging assay

The  scavenging activity of CA was determined by the method of Nishikimi et al. (1972) with slight modifications. One milliliter of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT; 100 μM of NBT in 100 mM PO4 buffer, pH 7.4), 1 ml of NADH (14.68 μM of NADH in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) and varying volumes of CA (20–100 μM) were mixed well. The reaction was started by the addition of 100 μM of phenazine methosulfate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm in a spectrophotometer with reagent blank containing double-distilled water instead of CA. Decreased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates increased

scavenging activity of CA was determined by the method of Nishikimi et al. (1972) with slight modifications. One milliliter of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT; 100 μM of NBT in 100 mM PO4 buffer, pH 7.4), 1 ml of NADH (14.68 μM of NADH in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) and varying volumes of CA (20–100 μM) were mixed well. The reaction was started by the addition of 100 μM of phenazine methosulfate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm in a spectrophotometer with reagent blank containing double-distilled water instead of CA. Decreased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates increased  scavenging.

scavenging.

|

Hydroxyl radical  scavenging assay

scavenging assay

The  scavenging activity was determined by the method of Halliwell et al. (1987). The incubation mixture in a total volume of 1 ml contained 0.1 ml of 100 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate–dipotassium hydrogen phosphate buffer, varying volumes of CA (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μM), 0.2 ml of 500 mM ferric chloride, 0.1 ml of 1 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 ml of 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 ml of 10 mM H2O2, and 0.2 ml of 2-deoxyribose. The contents were mixed thoroughly and incubated at room temperature for 60 min, then added with 1 ml of 1% thiobarbituric acid (1 g in 100 ml of 0.05 N NaOH) and 1 ml of 28% TCA. All the tubes were kept in a boiling water bath for 30 min. The absorbance was read in a spectrophotometer at 532 nm with reagent blank containing distilled water instead of CA. Decreased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates increased

scavenging activity was determined by the method of Halliwell et al. (1987). The incubation mixture in a total volume of 1 ml contained 0.1 ml of 100 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate–dipotassium hydrogen phosphate buffer, varying volumes of CA (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μM), 0.2 ml of 500 mM ferric chloride, 0.1 ml of 1 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 ml of 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 ml of 10 mM H2O2, and 0.2 ml of 2-deoxyribose. The contents were mixed thoroughly and incubated at room temperature for 60 min, then added with 1 ml of 1% thiobarbituric acid (1 g in 100 ml of 0.05 N NaOH) and 1 ml of 28% TCA. All the tubes were kept in a boiling water bath for 30 min. The absorbance was read in a spectrophotometer at 532 nm with reagent blank containing distilled water instead of CA. Decreased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates increased  scavenging activity.

scavenging activity.

|

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan’s multiple range test using Statistical Package for the Social Science software package version 12.00. Results were expressed as mean ± SD for six rats in each group. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Figure 1 shows the dose-dependent effect of CA in normal and experimental rats. The activity of serum CK was considerably (P < 0.05) increased in ISO-induced rats compared to normal control rats. Pretreatment with CA (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) daily for a period of 10 days considerably (P < 0.05) decreased the activity of serum CK in ISO-induced rats compared to ISO-induced rats. The effect exerted by 15 mg/kg of CA was better than the other two doses (5 and 10 mg/kg). Oral administration of CA (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) to normal rats did not show any effect compared to normal control rats. Hence, 15 mg/kg of CA showed the highest considerable effect, we have chosen only 15 mg/kg for our further study.

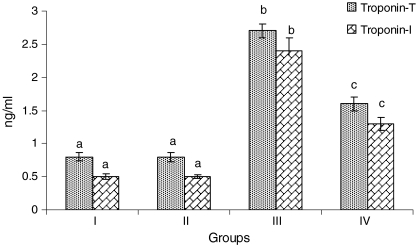

Figure 2 depicts the levels of serum cTnT and cTnI in normal and ISO-treated rats. Rats treated with ISO showed considerable (P < 0.05) elevation in the levels of serum cTnT and cTnI compared to normal control rats. Pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) daily for a period of 10 days to ISO-induced rats showed considerable (P < 0.05) decrease in the levels of serum cTnT and cTnI in ISO-induced rats compared with ISO alone treated rats.

Fig. 2.

Levels of serum cardiac troponins—T and I. Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letters (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

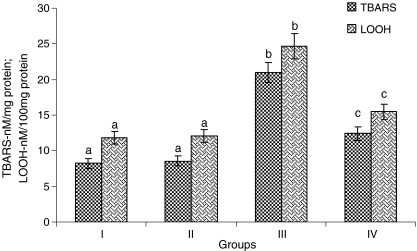

Rats treated with ISO showed considerable (P < 0.05) increased levels of TBARS and LOOH in the heart mitochondria compared to normal control rats. Oral pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) to ISO-induced rats considerably (P < 0.05) decreased the levels of TBARS and LOOH in the heart mitochondria compared with ISO alone induced rats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Levels of heart mitochondria thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH). Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letter (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

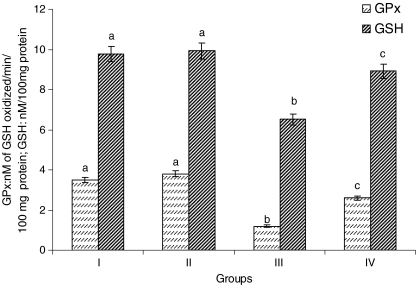

Rats treated with ISO showed considerable (P < 0.05) decrease in the activity of GPx and the level of GSH in the heart mitochondria compared to normal control rats. Pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) to ISO-induced rats considerably (P < 0.05) increased the activity of GPx and the levels of GSH in the heart mitochondria compared to ISO alone induced rats (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Activity of heart mitochondria glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and the levels of reduced glutathione (GSH). Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letter (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

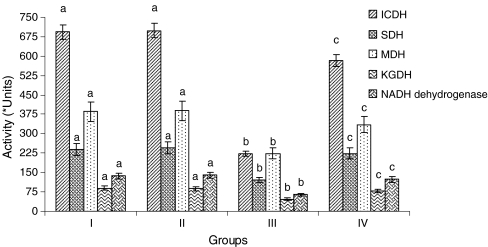

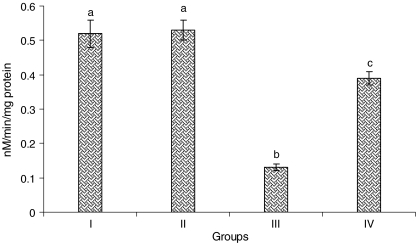

In ISO-treated rat’s heart mitochondria, the activities of ICDH, SDH, MDH, α-KGDH, NADH dehydrogenases (Fig. 5), and cytochrome-C-oxidase (Fig. 6) were decreased considerably (P < 0.05) compared to normal control rats. Pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) to ISO-induced rats considerably (P < 0.05) increased the activities of these enzymes compared to ISO alone induced rats.

Fig. 5.

Activities of the heart mitochondrial enzymes. Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letter (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test). Units: activity is expressed as nM of NADH oxidized/h/mg protein for ICDH; nM of succinate oxidized/min/mg protein for SDH; nM of NADH oxidized/min/mg protein for MDH; nM of ferro cyanide formed/h/mg protein for α-KGDH; nM of NADH oxidized/min/mg protein for NADH dehydrogenase

Fig. 6.

Activity of the heart mitochondria cytochrome-C-oxidase. Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letter (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

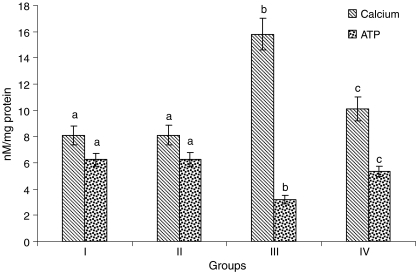

The levels of Ca2+ were considerably (P < 0.05) increased and the levels of ATP were considerably (P < 0.05) decreased in the heart mitochondria of ISO-induced rats. CA (15 mg/kg) pretreatment considerably (P < 0.05) decreased the levels of Ca2+ and considerably (P < 0.05) increased the levels of ATP in the heart mitochondria of ISO-induced rats (Fig. 7) compared to ISO alone induced rats.

Fig. 7.

Levels of calcium and adenosine triphosphate in heart mitochondria. Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letters (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

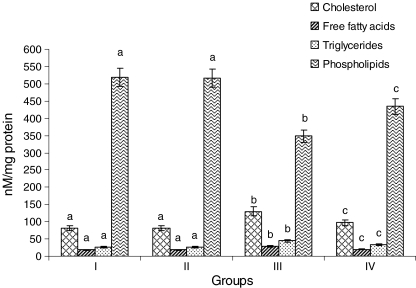

Figure 8 shows the levels of cholesterol, FFAs, TGs, and phospholipids in the heart mitochondria of normal and experimental rats. Rats treated with ISO showed considerable (P < 0.05) increased levels of cholesterol, FFAs, and TGs and considerable (P < 0.05) decreased levels of PLs in the heart mitochondria compared to normal control rats. Oral pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) to ISO-induced rats considerably (P < 0.05) decreased the levels of cholesterol, FFAs, and TGs and significantly (P < 0.05) increased the levels of PLs in the heart mitochondria compared with ISO alone induced rats.

Fig. 8.

Levels of lipids in the heart mitochondria. Group I normal control, Group II rats were treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg), Group III ISO-treated rats (100 mg/kg), Group IV rats were pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) + ISO (100 mg/kg). Each column is mean ± SD for six rats in each group; columns that have different letters (a, b, c) differ significantly with each other (P < 0.05; Duncan’s multiple range test)

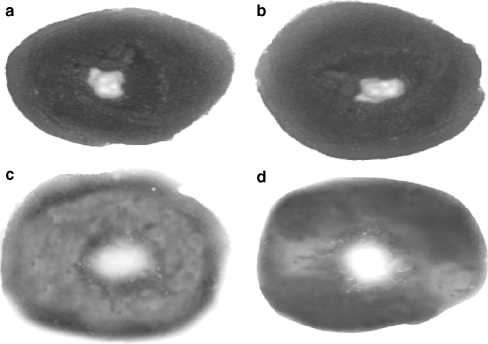

The size of the myocardial infarct determined by TTC macroscopic enzyme-mapping assay on the sections of heart is shown in Fig. 9a–d. Figure 9a indicates the section of the heart from normal control rats (Group I) with completely viable myocardial tissue stained with TTC to indicate the presence of LDH (bright red) and intact myocardial tissue. Figure 9b indicates the section of heart from rats pretreated with CA (Group II) shows results similar to that of normal control rats. Figure 9c shows the section of heart from ISO-induced rats (Group III). Infarcted tissues are clearly visible, pale gray, or colorless. Infarcted tissues do not stain with TTC because the enzyme LDH is leaked out from that area. Figure 9d shows the section of heart tissue of CA-pretreated rats administered with ISO (Group IV). A major portion of heart tissue stained positively for viability (mild LDH enzyme leakage) and the myocardial infarct size was much reduced. The results of Fig. 9d clearly revealed that prior oral administration of CA might have prevented membrane damage by ISO, thereby reducing myocardial infarct size and maintaining normal myocardial membrane structural and functional integrity (Group IV).

Fig. 9.

a–d Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride—macroscopic enzyme-mapping assay of heart. a Normal control rats heart showing completely viable myocardial tissue (LDH enzyme active) without infarction (Group I). b Normal rats treated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) heart showing results similar to that of normal control rats (LDH enzyme active; Group II). c ISO-treated rat’s (100 mg/kg), heart showing infarcted tissue does not stain with triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (enormous LDH enzyme leakage; Group III). d Rats pretreated with caffeic acid (15 mg/kg) to ISO-treated rats showing heart tissue stained positively for viability (mild LDH enzyme leakage) and much reduced infarct size (Group IV)

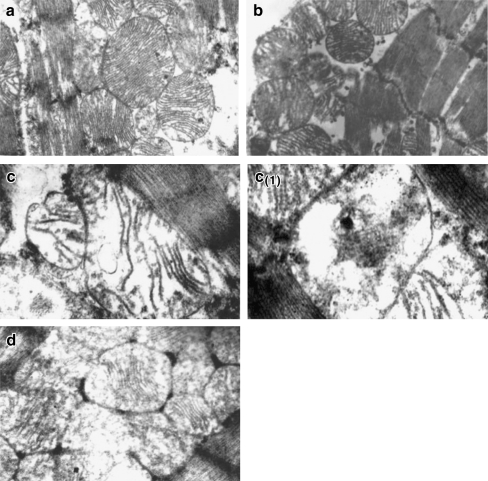

In the present study, the TEM images of the normal heart mitochondria (Group I) showed normal mitochondria with even arrangement of cristae (Fig. 10a). Normal rats treated with CA (Group II) showed normal mitochondria with intact myofibrils (Fig. 10b). But, ISO-induced rats (Group III) showed loss of cristae and swelling of mitochondria with change in shape and size (Fig. 10c). ISO-induced rats (Group III) also showed complete loss of cristae, mitochondrial damage with vacuolation (Fig. 10c (1)). CA-pretreated rats administered with ISO (Group IV) showed near normal mitochondria architecture with myofibrils (Fig. 10d).

Fig. 10.

(a, b, c, c1, d, e) Transmission electron microscopic study on the structure of heart mitochondria. a Normal mitochondria with even arrangement of cristae (Group I; ×20,000). b Normal rats administered with caffeic acid showing normal mitochondria with intact myofibrils (Group II; ×20,000). c ISO-treated rats showing loss of cristae and swelling of mitochondria and change in shape and size (Group III; ×20,000). c1 ISO-treated rat also showing complete loss of cristae, mitochondrial damage with vacuolation (Group III; ×20,000). d Caffeic-acid-pretreated rats administered ISO showing near normal mitochondrial architecture with myofibrils (Group IV; ×20,000)

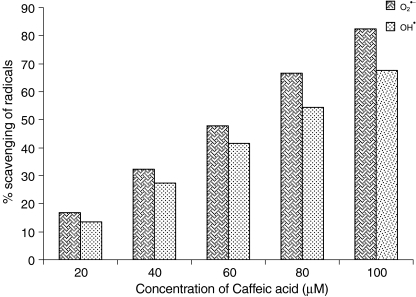

Figure 11 shows the percentage in vitro scavenging effects of CA on  and

and  . As shown in Fig. 11, CA scavenged these free radicals in vitro in a concentration-dependent manner (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM). The percentage scavenging activity of CA was increased with increasing concentration. The percentage scavenging effects of CA on

. As shown in Fig. 11, CA scavenged these free radicals in vitro in a concentration-dependent manner (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM). The percentage scavenging activity of CA was increased with increasing concentration. The percentage scavenging effects of CA on  at various concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM were found to be 16.67, 32.34, 47.81, 66.68, and 82.35, respectively. Furthermore, CA showed

at various concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM were found to be 16.67, 32.34, 47.81, 66.68, and 82.35, respectively. Furthermore, CA showed  scavenging effect in a dose-dependent manner (13.5%, 27.5%, 41.5%, 54.5%, and 68.5% for 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM of CA). Thus, CA at the dose of 100 µM concentrations showed the highest percentage

scavenging effect in a dose-dependent manner (13.5%, 27.5%, 41.5%, 54.5%, and 68.5% for 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM of CA). Thus, CA at the dose of 100 µM concentrations showed the highest percentage  scavenging activity of 82.35 than

scavenging activity of 82.35 than  scavenging activity of 68.5.

scavenging activity of 68.5.

Fig. 11.

In vitro scavenging effects of caffeic acid on superoxide anion  and hydroxyl radical

and hydroxyl radical

For all the biochemical parameters studied, CA (15 mg/kg) administration to normal rats did not show any significant effect. Also, administration of CA did not alter the structure of cardiac mitochondria. No changes were also observed in the myocardium (TTC assay).

Discussion

Previously, we reported the protective effects of CA on lipid peroxidation, antioxidants, and histopathological changes in the heart tissue of ISO-treated myocardial-infarcted rats (Senthil Kumaran and Stanely Mainzen Prince 2010). But in this study, we evaluated lipid peroxidation, antioxidants, marker enzymes of mitochondria, Ca2+, ATP, and lipids in the mitochondrial fraction of the heart. We also studied the protective effect of CA on the structure of heart mitochondria by TEM study and determined the infarct size of myocardium. In addition, in vitro studies on  and

and  were done to know the underlying mechanism of CA. Thus, the present study is done in mitochondrial fraction of the heart and entirely different from the previous study which was done with total heart tissue. In this study, we investigated more insight into the mechanisms of CA in ISO-induced myocardial-infarcted rats.

were done to know the underlying mechanism of CA. Thus, the present study is done in mitochondrial fraction of the heart and entirely different from the previous study which was done with total heart tissue. In this study, we investigated more insight into the mechanisms of CA in ISO-induced myocardial-infarcted rats.

The present study revealed pretreatment with CA protected cardiac mitochondria in ISO-treated rats. A dose-dependent study was conducted with three different doses on the effect of CA (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) in CK activity in ISO-treated rats. ISO causes an increase in the activity of serum CK. The increased activity of this enzyme in serum might be due to ISO- induced myocardial necrosis. Pretreatment with CA (5, 10, and15 mg/kg) dose dependently decreased the activity of serum CK in ISO-treated rats. But 15 mg/kg of CA elicited highest significant effect in reducing serum CK activity than the other two doses (5 and 10 mg/kg), we have chosen 15 mg/kg for our further study.

The primary function of measuring cardiac markers in blood is to detect the presence of myocardial injury. Cardiac troponins T and I have been shown to be highly sensitive and specific markers of myocardial cell injury (Alpert et al. 2000). These are contractile proteins that normally not found in the blood. They are released when myocardial necrosis occurs (Gupta and De Lemos 2007; Bertinchant et al. 2000). The observed increased levels of cardiac troponins T and I might be due to ISO-induced cardiac damage. Pretreatment with CA (15 mg/kg) decreased the levels of serum troponins T and I in ISO-induced rats. The observed effect of CA on CK and cardiac troponins T and I reveals the cardioprotective effect of CA due to its antioxidant action.

ISO induces oxidative stress and results in alterations of cardiac function and ultrastructure in experimental rats (Suchalatha et al. 2004). The positive inotropic and positive chronotropic response of ISO augments myocardial oxygen consumption (Harada et al. 1993). The increase in energy demands (Prabhu et al. 2000) and the decrease in blood flow induce an energy imbalance by the Ca2+ overload (Chagoya de Sanchez et al. 1997). This is accompanied by disruption of the mitochondria (Xia et al. 2002), with inactivation of TCA cycle enzymes and altered mitochondrial respiration (Prabhu et al. 2006a, b). Targeting the mitochondrial respiratory chain whose activity is decreased in ischemic conditions is a new approach with huge therapeutic prospective. Sparing of high-energy phosphates such as ATP during ischemia would preserve cellular integrity and functions during ischemia, but would also prevent ROS formation during reperfusion and full recovery. Due to ubiquitous localization and need for mitochondria, this approach may be useful for every pathological situation where ischemia takes place (Suchalatha et al. 2007).

Mitochondrial membrane contains relatively large amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in its phospholipids, which are highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation, an important deterioration in biological membrane (Halliwell and Gutteridge 1990). ISO induces lipid peroxidation in mitochondrial membrane (Tappel 1973). The process of lipid peroxidation is one of oxidative conversion of PUFAs to products known as malondialdehyde, which is usually measured as TBARS or lipid peroxides, which is the most studied, biologically relevant, free radical reaction (Bakan et al. 2002). The present study also showed that mitochondrial lipid peroxidation products (TBARS and LOOH) were increased during ISO administration. An increase in mitochondrial lipid peroxide level indicates enhanced lipid peroxidation by free radicals generated on ISO administration. Activated lipid peroxidation is an important pathogenic event in MI and the levels of lipid peroxide reflect the major stages of disease and its complications. CA pretreatment protected the heart mitochondrial membrane against lipid peroxidative damage by reducing the ISO-treated lipid peroxidation. The maintenance of mitochondrial lipid peroxide levels could be due to the ability of CA to scavenge free radicals.

ISO metabolism produces quinones, which reacts with oxygen to produce superoxide anions and H2O2 leading to oxidative stress and depletion of the endogenous antioxidant system. Depletion of mitochondrial GSH level seems to be a major mechanism for inducing an imbalance of mitochondrial function. A decrease in the activity of GPx makes mitochondria more susceptible to the ISO-induced damage, which leads to change in mitochondrial composition and function. The decrease in the activity of GPx observed in the ISO-induced rats is due to the reduced availability of its substrate, GSH. In this context, decreased levels of GSH were observed in the heart mitochondria of ISO-treated rats. Prior oral treatment with CA increased the activity of GPx and maintained the concentration of GSH in the ISO-induced rats. Increasing intracellular GSH can prevent cellular and mitochondrial damage. Thus, the increased levels of GSH prevented mitochondrial damage and protected cardiac mitochondria. This effect might be due to the antioxidant property of CA.

Decreased activities of TCA cycle enzymes were noted in ISO-treated rats. Reductions in the activities of TCA cycle enzymes prove a defect in aerobic oxidation of pyruvate, which might result in low production of ATP molecules. If oxygen delivery is interrupted and the balance between ATP production and consumption is disturbed, ATP concentration will decline and adenosine diphosphate, adenosine monophosphate, adenosine, and inorganic phosphate levels increase shifting from aerobic respiration to anaerobic glycolysis (Zarco and Henar Zarco 1996). ISO has been reported to cause tissue hypoxia, where there is oxygen demand and in hypoxic state the activities of TCA cycle enzymes are expected to be low (Manjula and Devi 1993). TCA cycle enzymes have been affected by free radicals produced by ISO. The enhanced activities of TCA cycle enzymes in CA-pretreated ISO-induced rats could be due to the ability of CA to scavenge ROS. Cytochrome-C-oxidase and NADH dehydrogenase are involved in the synthesis of ATP and are present in the inner mitochondrial membrane. These enzymes have an absolute requirement of cardiolipin for their activity. NADH dehydrogenase is an auto-oxidizable electron carrier responsible for a portion of free radical production in the mitochondria. Increased lipid peroxidation decreases the levels of total and readily oxidizable lipid, i.e., cardiolipin. The unavailability of cardiolipin lowers the activity of cytochrome-C-oxidase and NADH dehydrogenase in ISO-treated rats (Suchalatha et al. 2007). CA pretreatment was observed to prevent the decreased activities of cytochrome-C-oxidase and NADH dehydrogenase, due to the preventive action of CA on membrane phospholipid degradation. Thus, the improved activities of these enzymes might be one of the reasons for restoring normal mitochondrial function.

Mitochondrial calcium influx is one of the most common factors of inducing mitochondrial-derived ROS generation. The observed increased levels of mitochondrial calcium could be due to enhanced Ca2+ uptake by ISO-treated rats. The increased levels of heart mitochondria Ca2+ may inhibit the electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation or activate the key enzymes responsible for ROS generation leading to overproduction of ROS (Bel Chenko et al. 1990). There is a close association between ATP depletion and the metabolic changes on the onset of irreversible myocardial injury. During ischemia, a decrease in ATP content results in swelling, loss of ionic gradients, and alterations in mitochondrial membrane structure and function (Starkov et al. 2002). An increase in Ca2+ level (Sangeetha and Darlin Quine 2009) and a decrease in ATP level in heart mitochondria was also reported earlier in ISO-treated rats (Sivakumar et al. 2008). Pretreatment with CA decreased the levels of mitochondria Ca2+ and increased the levels of mitochondria ATP. The observed increased activities of TCA cycle and respiratory chain enzymes also resulted in increased levels of ATP in CA-pretreated ISO-treated rats. Thus, decreased levels of Ca2+ and increased levels of ATP in CA-pretreated ISO-induced rats maintains normal mitochondrial function and structure and this might be another reason for the protection of cardiac mitochondria.

Enhanced oxidative stress causes damage to the mitochondria resulting in the modification of mitochondrial lipids (Richter et al. 1988). Significant increased levels of mitochondrial cholesterol, FFAs, and TGs were observed in ISO-treated rats. Administration of ISO enhanced the levels of mitochondrial lipids, which is a clear evidence for altered cardiac function and ultrastructure. Sathish et al. (2003) have reported that the increase in the mitochondrial cholesterol content suggests the redistribution of cholesterol in the ischemic cell. The observed decreased concentration of phospholipids in cardiac mitochondrial fraction is due to enhanced activity of phospholipase A2 activity by Ca2+, which is an inducer of phospholipase A2. The increased level of FFAs is a consequence of changes in myocardial lipid metabolism. Excess free fatty acids inhibit respiratory activity and depress cardiac function in ischemic condition. In ischemic heart, hydrolysis of PLs prevails in myocardial mitochondria. These changes in the metabolism of the subcellular fractions may lead to damage of the membranes of the cardiac myocyte mitochondria. Oral pretreatment with CA restored the levels of mitochondrial lipids, indicating the activity of CA on maintaining the stability and integrity of mitochondrial membrane in the ISO-induced rats.

TTC staining is a well-accepted method to determine myocardial infarct size, which provides a reliable index of necrosis (Prabhu et al. 2006a, b). Myocardial necrosis can be detected by direct staining using TTC dye, which forms a red formazan precipitate with LDH of the viable myocardial tissue whereas the infarcted myocardium fails to stain with TTC. ISO-induced rat's heart showed increased myocardial infarct size with less TTC absorbing capacity, thus indicating a significant leakage of LDH as compared to normal control rats. CA (15 mg/kg) pretreatment decreased the infarct size with increased TTC absorbing capacity, thus indicating a mild leakage of LDH as compared to normal control rats. Thus, CA prevented membrane damage and decreased myocardial infarct size and protected the heart from ISO-treated MI.

TEM study of ISO-induced rats showed loss of cristae and swelling of mitochondria with change in shape and size. ISO-induced rats also showed complete loss of cristae, mitochondrial damage with vacuolation. CA-pretreated rats administered ISO showed near normal mitochondrial architecture with myofibrils. Thus, CA protected the structure of cardiac mitochondria.

ISO metabolism produces free radicals such as  and

and  . In order to know mechanism of action of CA, we have investigated the in vitro effects of CA on scavenging

. In order to know mechanism of action of CA, we have investigated the in vitro effects of CA on scavenging  and

and  . Radical scavenging activities are very important due to the deleterious role of free radicals in biological systems. It has been reported that

. Radical scavenging activities are very important due to the deleterious role of free radicals in biological systems. It has been reported that  radicals directly initiate lipid peroxidation (Wickens 2001).

radicals directly initiate lipid peroxidation (Wickens 2001).  is a precursor of active free radicals that have potential of reacting with biological macromolecules thereby inducing tissue damage.

is a precursor of active free radicals that have potential of reacting with biological macromolecules thereby inducing tissue damage.  radical is chiefly responsible for lipid peroxidation, which impairs the normal function of cell membranes. In this study, it was clear that CA is a potent free radical scavenger of

radical is chiefly responsible for lipid peroxidation, which impairs the normal function of cell membranes. In this study, it was clear that CA is a potent free radical scavenger of  and

and  in a dose-dependent manner. The highest percentage scavenging of these radicals was observed at the concentration of CA (100 µM). The present findings clearly demonstrated that CA is an effective free radical scavenger in various in vitro assays including

in a dose-dependent manner. The highest percentage scavenging of these radicals was observed at the concentration of CA (100 µM). The present findings clearly demonstrated that CA is an effective free radical scavenger in various in vitro assays including  and

and  . Thus, the free radicals such as

. Thus, the free radicals such as  and

and  produced excessively by ISO metabolism were quenched by CA and prevented lipid peroxidation and protected the cardiac mitochondria.

produced excessively by ISO metabolism were quenched by CA and prevented lipid peroxidation and protected the cardiac mitochondria.

Thus, CA reduced the extent of mitochondrial damage induced by ISO and restored normal cardiac mitochondrial function. The possible mechanisms for the observed effects of CA could be due to quenching the free radicals, improving multienzyme activities, increasing GSH levels, lowering lipids and Ca2+ and increasing ATP thereby improving cardiac mitochondrial structure and function. CA pretreatment also showed protective effects on cardiac troponins and CK in ISO-treated rats. In vitro studies also confirmed the free radical scavenging effects of CA.

In conclusion, these results suggest that CA could maintain cardiac mitochondrial structure and function in ISO-treated cardio toxic rats. This can also be evidenced from TEM photos of normal control and experimental rats. CA also decreased myocardial infarct size and protected heart from ISO-treated myocardial infarction. According to this study, CA does not have any adverse effects up to 15 mg/kg. Thus, it is a safe antioxidant. A diet containing CA may be beneficial to the heart. This study may provide a useful therapeutic option in myocardial infarction.

References

- Alpert JS, Thygesan K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakan E, Taysi S, Polat MF. Nitric oxide levels and lipid peroxidation in plasma of patients with gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:162–166. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyf035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bel Chenko DI, Sopka NV, Kalinkin MN, Khanina NIA, Chelnokov VS. The metabolic changes in myocardial subcellular fractions in the pathogenesis of ischemic heart disease. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter. 1990;2:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinchant JP, Robert E, Polge A, Marty-Double C, Fabbro-Peray P, Poirey S, Aya G, Juan JM, Ledermann B, Coussaye JE, Dauzat M. Comparison of the diagnostic value of cardiac troponin I and T determinations for detecting early myocardial damage and the relationship with histological findings after isoprenaline-induced cardiac injury in rats. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;298:13–28. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellari M, Sartini E, Fabiani A, Arfelli G, Amati A. Analysis of wine phenolics by high performance liquid chromatography using a monolithic type column. J Chromatogr A. 2002;973:221–227. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)01195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagoya de Sanchez V, Hernandez-Munoz R, Lopez Barrera F, Yanez L, Vidrio S, Suarez J, Cota-Garza MD, Aranda-Fraustro A, Cruz D. Sequential changes of energy metabolism and mitochondrial function in myocardial infarction induced by isoproterenol in rats: a long-term and integrative study. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:1300–1311. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-75-12-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono DP, Boon NA. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In: Edwards CRW, Boucheir IAD, editors. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. Hong Kong: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 249–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falholt K, Lund B, Falholt W. An easy colorimetric micromethod for routine determination of free fatty acids in plasma. Clin Chim Acta. 1973;46:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(73)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane SGH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Prencipe L. Serum triglycerides determined colorimetrically with an enzyme that produces hydrogen peroxide. Clin Chem. 1982;28:2077–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga CG, Leibovitz BE, Tappel AL. Lipid peroxidation measured as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in tissue slices: characterization and comparison with homogenate and microsomes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;4:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilski DJ, Borkenhagen B. Risk evaluation for cardiovascular health. Crit Care Nurse. 2005;25:26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulcin I. Antioxidant activity of caffeic acid. Toxicology. 2006;217:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Lemos JA. Use and misuse of cardiac troponins in clinical practice. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM, Aruoma OI. The deoxyribose methods: a simple ‘test tube’ assay for determination of rate constants for reactions of hydroxyl radicals. Anal Biochem. 1987;165:215–219. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K, Fukata Y, Miwa A, Kaneta S, Fukushima H, Ogawa N. Effect of KRN 2391, a novel vasodilator, on various experimental anginal models in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1993;63:35–39. doi: 10.1254/jjp.63.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann K. Flavonols and flavones in food plants: a review. J Food Technol. 1976;11:433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1976.tb00743.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZY, Hunt JV, Wolff SP. Ferrous ion oxidation in the presence of xylenol orange for detection of lipid hydroperoxide in low-density lipoprotein. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:384–389. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90122-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan K, Sarala Bai BR, Niranjali Devaraj S. Grape seed proanthocyanidins ameliorates isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats by stabilizing mitochondrial and lysosomal enzymes: an in vivo study. Life Sci. 2007;81:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. Isocitrate dehydrogenase. In: King JC, Van D, editors. Practical clinical enzymology. London: Nostrand Co; 1965. p. 363. [Google Scholar]

- Kono Y, Kobayashi K, Tagawa S, Adachi K, Ueda A, Sawa Y, Shibata H. Antioxidant activity of polyphenolics in diets: rate constants of reactions of chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid with reactive species of oxygen and nitrogen. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1335:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(96)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie JT, Pairolero PC, Holley KE, Titus JL. Macroscopic enzyme-mapping verification of large, homogeneous, experimental myocardial infarcts of predictable size and location in dogs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;69:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin’s-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjula TS, Devi CS. Effect of aspirin on mitochondrial lipids in experimental myocardial infarction in rats. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;29:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila P, Kumpulainen J. Determination of free and total phenolic acids in plant-derived foods by high performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3660–3667. doi: 10.1021/jf020028p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler AH, Kornberg A, Grisolia S, Ochoa S. The enzymatic mechanims of oxidation-reductions between malate or isocitrate or pyruvate. J Biol Chem. 1948;174:961–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakami S, Ringler RL, Singer TP. Studies on the respiratory chain-linked dihydro diphospho pyridine nucleotide dehydrogenase I: assay of the enzyme in particulate and in soluble preparations. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:569–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ, Edwards LM, Clarke K. Mitochondria and heart failure. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:704–711. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f0ecbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M, D’Aquino M, Tomassi G, Gentili V, Felice M, Scaccini C. Inhibition of human low-density lipoprotein oxidation by caffeic acid and other hydroxy cinnamic acid derivatives. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:541–552. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00052-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcinogens and anticarcinogens in the human diet. Washington: National Academy; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikimi M, Appaji N, Yagi K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1972;46:849–853. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(72)80218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl W, Cascarano J, Zweifach BW. Microdetermination of cytochrome oxidase in rat tissues by the oxidation on N-phenyl-p-phenylene diamine or ascorbic acid. J Histochem Cytochem. 1963;11:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu SD, Chandrasekar B, Murray DR, Freeman GL. Beta-adrenergic blockade in developing heart failure: effects on myocardial inflammatory cytokines, nitric oxide, and remodeling. Circulation. 2000;101:2103–2109. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S, Jainu M, Sabitha KE, Devi CS. Role of mangiferin on biochemical alterations and antioxidant status in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006a;107:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S, Jainu M, Sabitha KE, Shyamala Devi CS. Effect of mangiferin on mitochondrial energy production in experimentally induced myocardial infarcted rats. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006b;44:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psotova J, Lasovsky J, Vicar J. Metal-chelating properties, electrochemical behavior, scavenging and cytoprotective activities of six natural phenolics. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2003;147:147–153. doi: 10.5507/bp.2003.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Mukherjee RB. Alpha ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex from Escherichia coli. In: Lowenstein JM, editor. Methods in enzymology. London: Academic; 1969. pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Park JW, Ames BN. Normal oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA is extensive. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6465–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, Hoekstra WG. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179:588–590. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4073.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeena Farvin KH, Anandan R, Kumar SH, Shiny KS, Sankar TV, Thankappan TK. Effect of squalene on tissue defense system in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2004;50:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha T, Darlin Quine S. Preventive effect of S-allyl cysteine sulphoxide (Alliin) on mitochondrial dysfunction in normal and isoproterenol induced cardio toxicity in male Wistar rats: a histopathological study. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;328:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathish V, Ebenezar KK, Devaki T. Biochemical changes on the cardioprotective effect of nicorandil and amlodipine during experimental myocardial infarction in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2003;48:565–570. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senthil Kumaran K, Stanely Mainzen Prince P (2010) Protective effect of coffee acid on cardiac markers and lipid peroxide metabolism in cardiotoxic rats: an in vivo and in vitro study. Metabol Clin Exp. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar R, Anandh Babu PV, Shyamaladevi CS. Protective effect of aspartate and glutamate on cardiac mitochondrial function during myocardial infarction in experimental rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;176:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater EC, Borner WD., Jr The effect of fluoride on the succinic oxidase system. Biochem J. 1952;52:185–196. doi: 10.1042/bj0520185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkov AA, Polster BM, Fiskum G. Regulation of hydrogen peroxide production by brain mitochrondria by calcium and Bax. J Neurochem. 2002;83:220–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchalatha S, Thirugnanasambandam P, Maheswaran E, Shyamala Devi CS. Role of Arogh, a polyherbal formulation to mitigate oxidative stress in experimental myocardial infarction. Ind J Exp Biol. 2004;42:224–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchalatha S, Srinivasan P, Shyamala Devi CS. Effect of T. chebula on mitochondrial alterations in experimental myocardial injury. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;169:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sushama Kumari S, Jayadeep A, Kumar JS, Menon VP. Effect of carnitine on malondialdehyde, taurine and glutathione levels in heart of rats subjected to myocardial stress by isoproterenol. Ind J Exp Biol. 1989;27:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasawa M, Hayakawa M, Sugiyama S, Hattori K, Ito T, Ozawa T. Age-associated damage in mitochondrial function in rat hearts. Exp Gerontol. 1993;28:269–280. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(93)90034-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappel AL. Lipid peroxidation damage to cell components. Fed Proc. 1973;32:1870–1874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler BC, Greenberg BP. Protective effects of clofibrate on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in arteriosclerotic and non-arteriosclerotic rats. Atherosclerosis. 1978;29:373–375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(78)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens AP. Ageing and the free radical theory. Respir Physiol. 2001;128:379–391. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(01)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Coorkey BE. Assay of intermediates of the citric acid cycle and related compounds by flourimetric enzymatic methods. In: Lowenstein JM, editor. Methods in enzymology. New York: Academic; 1967. pp. 488–492. [Google Scholar]

- Xia T, Jiang C, Li L, Wu C, Chen Q, Liu SS. A study on permeability transition pore opening and cytochrome-c-release from mitochondria, induced by caspase-3 in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2002;510:62–66. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarco P, Henar Zarco MH. Biochemical aspects of cardioprotection. Medicographia. 1996;18:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zilversmit DB, Davis AK. Microdetermination of plasma phospholipids by trichloro aectic acid precipitation. J Lab Clin Med. 1950;35:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatkis A, Zak B, Boyle AJ. A new method for the direct determination of serum cholesterol. J Lab Clin Med. 1953;41:486–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]