Abstract

Cancer cells are exposed to external and internal stresses by virtue of their unrestrained growth, hostile microenvironment, and increased mutation rate. These stresses impose a burden on protein folding and degradation pathways and suggest a route for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Proteasome and Hsp90 inhibitors are in clinical trials and a 20S proteasome inhibitor, Velcade, is an approved drug. Other points of intervention in the folding and degradation pathway may therefore be of interest. We describe a simple screen for inhibitors of protein synthesis, folding, and proteasomal degradation pathways in this paper. The molecular chaperone-dependent client v-Src was fused to firefly luciferase and expressed in HCT-116 colorectal tumor cells. Both luciferase and protein tyrosine kinase activity were preserved in cells expressing this fusion construct. Exposing these cells to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin caused a rapid reduction of luciferase and kinase activities and depletion of detergent-soluble v-Src::luciferase fusion protein. Hsp70 knockdown reduced v-Src::luciferase activity and, when combined with geldanamycin, caused a buildup of v-Src::luciferase and ubiquitinated proteins in a detergent-insoluble fraction. Proteasome inhibitors also decreased luciferase activity and caused a buildup of phosphotyrosine-containing proteins in a detergent-insoluble fraction. Protein synthesis inhibitors also reduced luciferase activity, but had less of an effect on phosphotyrosine levels. In contrast, certain histone deacetylase inhibitors increased luciferase and phosphotyrosine activity. A mass screen led to the identification of Hsp90 inhibitors, ubiquitin pathway inhibitors, inhibitors of Hsp70/Hsp40-mediated refolding, and protein synthesis inhibitors. The largest group of compounds identified in the screen increased luciferase activity, and some of these increase v-Src levels and activity. When used in conjunction with appropriate secondary assays, this screen is a powerful cell-based tool for studying compounds that affect protein synthesis, folding, and degradation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12192-010-0200-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Molecular chaperone, Ubiquitin pathway, High-throughput screen, v-Src, Hsp70, Hsp90

Introduction

Genetic or pharmacological disruption of molecular chaperone function is deleterious to cell survival, while increased cellular stress in the form of upregulated molecular chaperone activity occurs during oncogenic transformation (Solit and Rosen 2006; Miyata 2005; Dey et al. 1996a, b; Kimura et al. 1995, 1997; Chang et al. 1997; Xu and Lindquist 1993; Calderwood et al. 2006). Of the several proteins with functional roles in molecular chaperone complexes, Hsp90 has received the most attention as a potential drug target. Several natural products and small-molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 have advanced to clinical trials: geldanamycin derivatives, 17-AAG (17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) and 17-DMAG (17-dimethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) and IPI-504 (Sharp and Workman 2006; Taldone et al. 2008), purine (CFN-2024) and resorcinol analogs (NPV-AUY922), and an unrelated 6,7-dihydro-indazol-4-one inhibitor SNX-5422 (Kasibhatla et al. 2007; Sharp et al. 2007; Brough et al. 2008; Jensen et al. 2008). These inhibitors share an ability to bind to the N-terminal ATPase domain of Hsp90 and thereby block its folding activity (Workman et al. 2007).

Protein folding pathways regulated by chaperones intersect with ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathways (McDonough and Patterson 2003). Proteins inactivated by stress and deemed beyond repair by the chaperone machinery are polyubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome (Dahlmann 2005; McClellan et al. 2005). Proteasome inhibitors that block the activity of the 20S subunit and cause a buildup in ubiquitinated proteins have been described, and one, Velcade, is approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma patients (Adams et al. 1999; Kane et al. 2006). Dual inhibition of Hsp90 and the 20S proteasome causes a greater buildup in polyubiquitinated proteins than treatment with 20S inhibitors alone (Mimnaugh et al. 2004). Further indication of the benefit of simultaneous functional diminution of two components of the folding or degradation pathway is seen with knockdown of Hsp70 or Hsp27, which improves the antiproliferative activity of geldanamycin (McCollum et al. 2006; Guo et al. 2005). Hsp90 is also inactivated by acetylation in cells treated with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, and HDAC inhibition sensitizes tumor cells to Hsp90 inhibitors (Bali et al. 2005; Scroggins et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2008). These results suggest that whatever the outcome of clinical trials currently underway with Hsp90 inhibitors, there is considerable room for improving a given therapeutic outcome by attacking other components of the folding and degradation pathways in tumor cells.

Cell-based screens for the identification of agents that act on molecular chaperone complexes have been described (Zaarur et al. 2006; Hardcastle et al. 2007). These screens allow the characterization of different routes to modulating the stress response. Here, we describe a novel, simple screen using a well-understood chaperone-dependent protein tyrosine kinase v-Src. Nascent v-Src is found in a high-molecular-weight complex consisting of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp40, Cdc37, Sti1 (Hop1), Aha1, among others (Dey et al. 1996a, b; Kimura et al. 1995, 1997; Chang et al. 1997; Xu and Lindquist 1993; Lotz et al. 2003). Loss of Hsp90, Cdc37, Hsp40, Aha1, or Sti1 activity results in the inactivation and destabilization of v-Src (Chang et al. 1997; Xu and Lindquist 1993; Dey et al. 1996a, b; An et al. 2000; Lotz et al. 2003).

These results suggest that v-Src would be a good probe for chaperone function in a cell-based screen. We therefore used a reporter assay with v-Src fused to firefly luciferase such that both v-Src tyrosine kinase activity and firefly luciferase activity were preserved in the fusion protein when it was expressed in HCT-116 human colorectal tumor cells. When these cells were treated for 3–5 h with geldanamycin, luciferase activity was diminished in the HCT-116 line expressing the v-Src::luciferase fusion, but not in HCT-116 cells expressing native firefly luciferase. The tyrosine kinase activity and levels of v-Src::luciferase were also reduced by geldanamycin treatment. Other compounds that reduce the luciferase activity of the v-Src::luciferase fusion protein but not native luciferase include protein synthesis inhibitors and ubiquitin pathway inhibitors. Histone deacetylase inhibitors have an opposite effect, increasing v-Src::luciferase levels and activity. Hsp70 knockdown reduced v-Src::luciferase levels and potentiated the effects of geldanamycin treatment. This assay was used as a mass screen for chaperone pathway inhibitors. Here, we describe the validation of this screen.

Materials and methods

Cell line construction

The v-src–luciferase fusion gene was made by constructing a gene fusion between the v-src gene [Prague C (PrC) variant of Rous sarcoma virus; Protein Database accession no. P00526] and firefly luciferase. The PrC v-src gene was obtained from a plasmid pBamSrc described in Wendler and Boschelli (1989). The firefly luciferase gene was obtained from the commercially available plasmid pGL3 (Promega). The fusion gene was created by cloning the firefly luciferase gene to the 3′ end of the v-src ORF to yield the sequence shown in Supplementary Material. The native firefly and renilla luciferase genes, along with the fusion gene, were cloned distal to the CMV promoter in pIRESneo2 (Clontech). HCT-116 human colorectal tumor cells (ATCC) were transfected with pFFluc and pRenLuc (Promega) or with pv-Src::luciferase and pRenLuc. Clones expressing these genes were selected with G418 [firefly Luc, v-Src::Luc, and (RenLuc)]. BT474 cells were obtained from ATCC.

Antibodies and reagents

Geldanamycin, puromycin, lactacystin, MG132, emetine, cycloheximide, anisomycin, mitoxanthrone, methotrexate, vincristine, fluorouracil, cisplatin, paclitaxel, trichostatin, azacytidine, camptothecin, triptolide, novobiocin, and valproic acid were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis) or were present in the in-house compound library. Vorinostat (SAHA) was obtained from the Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor). Antibodies were obtained as follows: ubiquitin (Upstate), 4G10 (Upstate), v-Src (Calbiochem, Mab327), Her2 (Upstate), luciferase (Upstate), actin (Chemicon), and Hsp70 (BD Transduction or Stressgen (SPA-802), Ann Arbor). Cell culture medium, serum, and supplements were obtained from Invitrogen or Mediatech. Silencing RNAs were ordered from Dharmacon (Dharmacon; Waltham, MA). Hsc70 and Hsp70 siRNAs were as described in Powers et al. (2008) targeting Hsp72 (HSPA1A) and Hsc70 (HSPA8) along with two scrambled controls. Two sequences for Hsp72, HSP72A (5′-GGACGAGUUUGAGCACAAG-3′) and HSP72B (5′-CCAAGCAGACGCAGAUCUU-3′), along with internal control, HSP72IC (5′GGACGAGUUGUAGCACAAG 3′), were made. Two sequences against HSC70, HSC70A (5′-CCGAACCACUCCAAGCUAU-3′), and HSC70B (5′-CUGUCCUCAUCAAGCGUAA-3′) as well as control HSC70IC (5′-CCGAACCACCUCAAGCUAU-3′) were synthesized. HCT116 v-Src::luciferase cells were transfected using Optifect reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Cells were transfected with either mock, 200 nM Hsp70IC, 100 nM HSP72A/HSP72B+100 nM HSC70IC, 100 nM HSC70A/HSC702B+100 nM HSP72IC, or 100 nM HSP72A/HSP72B+100 nM HSC70A/HSC702B.

Luciferase assays

Forty thousand cells per well were plated the day before compound addition in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, glutamine, non-essential amino acids, and pen/strep. Compound was added the next day and incubation continued for 3–6 h as indicated. Luciferase reagents were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI).

Lysate preparation

Three types of extracts were prepared: “soluble,” “insoluble,” and “whole cell” lysates. Cells were washed three times with cold PBS and then extracted with NP40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5 rt, 0.1 M NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA supplemented with freshly added sodium orthovanadate to 1 mM and Protease Inhibitor cocktail I (Calbiochem) as recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were incubated for 20 min followed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf 5417R refrigerated microcentrifuge for 20 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatant was saved as the “soluble” lysate. Insoluble lysates were prepared by suspending the pellets from the NP40 extraction procedure in lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Invitrogen). Whole cell lysates were prepared by adding LDS sample buffer directly to cell pellets after the PBS wash.

Hsp90 fluorescence polarization binding assay

Full-length Hsp90 alpha protein (Stressgen) at a final concentration of 30 nM was incubated for 10 min with test compound in assay buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 50 mM KCl, 20 mM NaMoO4, 0.01% NP40, 2 mM DTT, and 0.1 mg/mL bovine gamma globulin (Panvera P2045). Bodipy-labeled geldanamycin was added to 5 nM final concentration, and the incubation was allowed to proceed with gentle rocking for 3 h. Fluorescence polarization was measured on a Wallac Envision reader with 480-nM excitation filter and a polarized 535-nM filter.

Methionine incorporation assay

HCT-116 v-Src::luciferase cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated overnight. The medium was removed and cells were rinsed twice with methionine-deficient DMEM. Fresh medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum was added and incubated for 30 min. Medium was removed and fresh medium added to the cells. Compounds were added and the plate was gently rocked for 1 min and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Tritiated methionine (2 μCi/well) was added and the cells were incubated for a further hour at 37°C. At this time, the medium was removed and cells were washed one time with cold PBS. Fifty microliters of 1% NP40 in PBS was added and cells were rocked at high speed for 1 min. Ten microliters of the lysate was transferred to a fresh 96-well plate and shaken for 1 min with 10 uL of 20% trichloroacetic acid. The plate was incubated on ice for 30 min, after which 30 uL of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added. The precipitates were collected with a Skatron harvester (Lier, Norway) onto glass fiber filters and read in a scintillation counter.

20S proteasome assay

The Biomol Quantizyme 20S Proteasome Assay (Plymouth Meeting, PA) was used as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, human erythrocyte 20S proteasome was incubated with inhibitor at 1 and 10 μg/mL in assay buffer at 30°C. (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.05% NP40, and 0.03% sodium dodecyl sulfate). Fluorogenic substrate (succinate-LLVY-AMC, final concentration of 75 μM) was added and the reaction was allowed to proceed at 30°C for 30 min. Plates were read on an Envision with 360-nm excitation and 460-nM emission filters.

Luciferase refolding assay

Hsp72 and Hsp40 were ordered from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI; Hsp72: NSP-55F; Hsp40 (Hdj1): SPP-400F). Firefly luciferase was ordered from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Luciferase was denatured by mixing 1:1 with 2× denaturing buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM KAc, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 12 M guanidine HCl, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 25 μg/mL bovine serum albumin) for 1 h at 27°C. This protein was then mixed with Buffer A (25 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 50 mM KAc, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 25 μg/mL BSA) at a ratio of 1:40 (luciferase/Buffer A) and incubated on ice for 20 min. The refolding reaction was initiated by adding 1 volume of a 5:1 mixture of Hsp70:Hsp40 in buffer A to 1 volume of a mixture of compound (or DMSO at a final concentration of 1%), ATP (final concentration of 1 mM), and denatured luciferase (20 μg/mL final concentration). The mixture was incubated for 2 h, after which SteadyGlo (Promega) was added. Luminescence was measured on an Envision detector.

mRNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time PCR

Poly(A)-tailed mRNA was isolated using the mRNA Catcher PLUS plate (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After hybridization and washing, the purified mRNA was directly reverse-transcribed into cDNA in the well using iSCRIPT cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research). The synthesized cDNA was diluted with RNase/DNase-free water and mixed with FAM-labeled TaqMan probe sets specific for p38α, v-src, or PPIB (Applied Biosystems), respectively. The QuantiFast Probe PCR +ROX vial kit (Qiagen) was used to perform quantitative real-time PCR on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories): 3 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 3 s at 95°C, and 30 s at 60°C. The mean CT value of triplicate samples was determined, and the CT values were normalized to cyclophilin B (PPIB). The results represent the average of two independent experiments.

Results

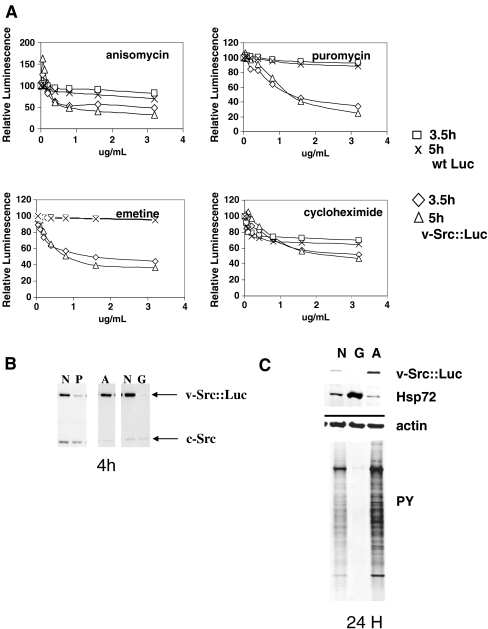

Stably transfected HCT-116 colon tumor cells (ATCC) expressing the v-Src–firefly luciferase fusion protein or native firefly luciferase were isolated by G418 selection followed by screening for luciferase activity. The kinase activity of the v-Src::luciferase fusion protein was confirmed by immunoblotting for v-Src, luciferase, and for total cellular phosphotyrosine (Fig. 1a). The effect of the known Hsp90 inhibitor, geldanamycin (GA), on the luciferase and v-Src activities in the two lines was then determined. A rapid, dose-dependent reduction in luciferase activity of the fusion protein occurred upon addition of GA to cells (Fig. 1b), while native firefly luciferase remained largely resistant to GA treatment. Similarly, GA treatment reduced the level of v-Src::luciferase after treatment for 4 h (Fig. 1c), but had little effect on endogenous c-Src. The rapidity of the v-Src::Luc fusion protein depletion in response to GA treatment closely parallels that reported for native v-Src. GA treatment also reduced total phosphotyrosine levels (Fig. 1d) and caused an increase in protein ubiquitination in the same timescale in both the native firefly luciferase cell line and the v-Src::luciferase cell line (Fig. 1 e). The v-Src::luciferase HCT116 line therefore provides a rapid means of monitoring the effect of Hsp90 inhibitors in cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of geldanamycin treatment on luciferase and Src activity in the HCT116 v-Src::luciferase cell line. a Immunoblot showing v-Src::luciferase expression and kinase activity in extracts from HCT116 cells expressing either v-Src::luciferase or native firefly luciferase. The arrows note the v-Src::luciferase protein and the major phosphotyrosine band that co-migrates with v-Src::luciferase. b Graphical representation of the rapid dose-dependent reduction in luciferase activity in the v-Src::luciferase line upon treatment with various concentrations of geldanamycin (GA) for 3.5 or 5 h. c Immunoblot showing reduced levels of v-Src::luciferase but not endogenous c-Src after treatment with 1 µg/mL geldanamycin for 4 h. d Immunoblot showing reduced v-Src activity relative to total actin, as measured by total protein phosphorylation on tyrosine after 4-h treatment with 1 µg/mL geldanamycin. e Immunoblot showing increased levels of ubiquitinated proteins after 4-h treatment with 1 µg/mL geldanamycin

Effect of Hsp70 downregulation on v-Src::luciferase expression and activity

The Hsp70 co-chaperone Ydj1 aids in v-Src folding, and Hsp70 is found in reconstituted chaperone complexes with v-Src, suggesting that Hsp70 itself is an important agent for v-Src biogenesis.(Hutchison et al. 1992; Dey et al. 1996a; Kimura et al. 1995) We examined this possibility by siRNA-mediated knockdown of the cognate Hsc70 (Hsp73) and inducible Hsp70 (Hsp72). The oligonucleotide set described by Powers et al. (2008) was used to target Hsc73 and both isoforms of Hsp72. We examined the effects of individual knockdowns of Hsc70 and Hsp70 alongside concomitant knockdown of both Hsc70 and Hsp70 on v-Src::luciferase activity. We also examined the effect of Hsp90 inhibition in the context of Hsc/Hsp70 knockdown. Unlike the case with Hsp90 inhibition by geldanamycin, both v-Src::luciferase and native firefly luciferase activity were reduced by dual knockdown of Hsc73/Hsp72 (Fig. 2a). Although these data suggest that Hsp70 depletion might be even more pleiotropic than the effects of Hsp90 inhibition, it is possible that the extended time required for effective knockdown may mask any selective effect of Hsp70 knockdown on v-Src::luciferase levels compared to native luciferase.

Fig. 2.

Effects of siRNA-mediated Hsp70 knockdown in the HCT116 v-Src::luciferase line. Cells were plated on day 0, transfected on day 1, treated with 0.1% DMSO or 1 μM geldanamycin on day 3, and treated with Steady Glo to measure luciferase activity or lysed to measure protein levels on day 4. a Relative luciferase activity in the transfected cells. b Detergent-soluble lysates. Blots of protein lysates prepared in buffer with 1% NP-40. c Detergent-insoluble lysates. Blots of pellets from the detergent-soluble lysates solubilized with LDS lysis buffer probed with the indicated antibody

In further experiments to characterize any role for Hsp70 in v-Src::luciferase function, we fractionated the cell extracts of transfectants into NP40-soluble or insoluble fractions. As shown in Fig. 2b, v-Src::luciferase levels were modestly affected by dual knockdown Hsc/Hsp70. Hsp70 knockdown had no effect, while Hsc70 knockdown had at best a minimal effect on v-Src::luciferase levels. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from a parallel transfection showed 70% reduction in either Hsc70 or Hsp70 mRNA levels by the respective siRNAs. Hsc70 knockdown increased Hsp70 RNA levels about fivefold, while Hsp70 knockdown had no effect on Hsc70 levels, as expected. The double knockdown brought Hsc70 levels to 50% of untreated and Hsp70 mRNA levels to 1.5 times the untreated levels. The v-Src::luciferase mRNA levels were not appreciably changed by Hsc/Hsp70 knockdown. Protein phosphorylation on tyrosine was slightly reduced, while protein ubiquitination was mostly unaffected by the dual Hsc/Hsp70 knockdown.

Addition of geldanamycin to these samples reduced v-Src::luciferase and phosphotyrosine-containing protein levels in the NP40-soluble fraction in all samples, with no effect on protein ubiquitination. In the NP-40-insoluble samples, increased v-Src::luciferase and ubiquitinated protein levels were observed in the Hsp70 or dual Hsc/Hsp70 knockdown samples. Since Hsp70 levels were still induced in the geldanamycin-treated samples, the effects observed might only approximate the effects of more complete inhibition of Hsp70 activity by an inhibitor. Even given this caveat, the significant buildup of ubiquitinated proteins in the detergent-insoluble fraction suggests that combined inhibition of Hsp90 and Hsp70 would disrupt both the folding and degradation pathways.

Effect of inhibiting ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis

In agreement with the results reported by others, the data in Fig. 1d indicate that Hsp90 inhibition increased the levels of ubiquitinated proteins. Since protein folding and degradation are coupled processes, blocking the overall degradation of ubiquitinated proteins could affect the equilibrium between v-Src::luciferase folding and degradation. Therefore, we examined whether known proteasome inhibitors affected v-Src::luciferase activity. Figure 3a indicates that MG-132 and lactacystin treatment reduced the luciferase activity of the v-Src::luciferase fusion protein more than native luciferase. As expected, these agents increase the levels of ubiquitintated proteins in whole cell extracts and also cause smearing of phosphotyrosine-containing bands on the blots of NP-40 solubilized extracts (Fig. 3b). Proteasome inhibitor treatment also caused a small increase in ubiquitinated proteins and a large increase in phosphotyrosine-containing proteins in the NP-40 insoluble fraction. These data indicate that proteasome inhibitors would be detected in this assay.

Fig. 3.

Effects of proteasome inhibitors on v-Src::luciferase levels and activity in the screening cell line. a Dose–response showing the effect of 1 μg/mL geldanamycin (G), 3 μg/mL lactacystin (L), or 3 μg/mL MG-132 on luciferase activity in the v-Src::luciferase (left) or native luciferase (right) lines after 4-h treatment. b Immunoblot showing the effects of proteasome inhibitors on phosphotyrosine-containing proteins and protein ubiquitination in the v-Src::luciferase line. Left NP-40 soluble fraction. Right NP-40 insoluble fraction resuspended in LDS PAGE buffer

Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors

Downregulation of HDAC activity increases acetylation of Hsp90 and reduces its chaperone activity (Murphy et al. 2005; Scroggins et al. 2007; Kovacs et al. 2005). To determine if v-Src::luciferase activity was sensitive to HDAC inhibition, three histone deacetylase inhibitors were examined in the v-Src::luciferase assay: valproic acid, trichostatin, and vorinostat (Fig. 4). All three agents caused a small but reproducible increase in luciferase activity in the v-Src::luciferase-expressing cell line at concentrations consistent with their known cellular activity (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, this effect is specific to the presence of v-Src since native firefly luciferase activity was unaffected by vorinostat. Immunoblot analysis showed that small but significant increases in v-Src::luciferase levels and activity occurred, whereas geldanamycin treatment had the opposite effect (Fig. 4b). Hsp70, Hsp90, and total protein ubiquitination were not affected under conditions where GA increased Hsp70 and protein ubiquitination. These results were unexpected in view of known effects of HDAC inhibitors on reducing Hsp90 activity. Since HDAC inhibitors are also reported to increase CMV promoter activity, we examined the effects of vorinostat treatment on v-Src::luciferase RNA levels by RT-PCR and observed increased v-Src::luciferase message levels of 219% and 169% relative to DMSO-treated samples in separate experiments. Since native firefly luciferase activity was not affected by vorinostat, it is not clear that the increased protein levels and activity are solely a function of transcriptional effects. Nonetheless, these observations suggest that HDAC inhibitors might be detected in the screen.

Fig. 4.

Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors valproic acid, vorinostat, and trichostatin on luciferase activity after 4 h (left) or NP-40 soluble v-Src::luciferase, total phosphotyrosine, and protein ubiquitination levels in the v-Src::luciferase line after 4.5-h (right) treatment with 0.1% DMSO (1); 3 mM valproic acid (2); 10 µM vorinostat (3); 2 µM geldanamycin (4); 3.3 µM trichostatin (5); and 10 µM trichostatin (6)

Effect of protein synthesis inhibition

The v-Src protein has a relatively short half-life in cells (Sefton et al. 1982). Therefore, compounds that block protein synthesis could also reduce v-Src levels, and hence luciferase activity, under conditions used in a high-throughput screen. To examine this possibility, the effect of known protein synthesis inhibitors cycloheximide, emetine, anisomycin, or puromycin on luciferase activity was determined (Fig. 5). Puromycin, emetine, and anisomycin effectively reduced v-Src::luciferase activity during a 4-h period, while cycloheximide was less effective. Anisomycin and cycloheximide were less selective in their effect, as shown by the relatively greater reduction of native firefly luciferase activity. In the case of puromycin, the decrease in luciferase activity was accompanied by reduced levels of v-Src::luciferase protein, suggesting that like native v-Src, the v-Src::luciferase fusion protein is also relatively short-lived. Anisomycin, on the other hand, had less of an effect on v-Src::luciferase levels during the time frame of this assay (Fig. 5b). In addition, at low concentrations, anisomycin treatment increased luciferase activity, and the increase was greater after 5 h than after 3.5 h of treatment. Increased v-Src::luciferase levels and phosphotyrosine levels were sometimes observed when cells were treated for 4–6 h with low concentrations of anisomycin (not shown). However, when the incubation time was extended to 24 h and lower concentrations of anisomycin were used, v-Src levels and activity increased in a reproducible manner (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Effects of known protein synthesis inhibitors on v-Src::luciferase and native luciferase activities. a Dose–response curves showing the effect of treatment with anisomycin, puromycin, emetine, or cycloheximide on native luciferase or v-Src::luciferase activities for the indicated times. b Immunoblot showing the effect of 3.2 µg/mL puromycin (P) and anisomycin (A) or 1 µg/mL geldanamycin (G) on v-Src::luciferase levels after a 4-h treatment. c Immunoblot showing the effect of 24-h treatment with 50 ng/mL anisomycin or 1 µM geldanamycin on v-Src::luciferase, Hsp72, and total phosphotyrosine levels

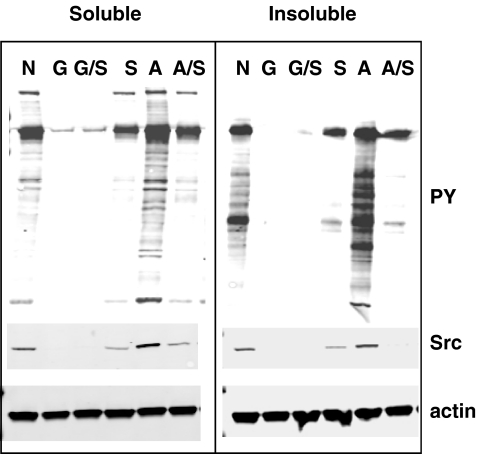

In addition to inhibiting protein synthesis, anisomycin activates p38 stress kinases. To determine whether p38 might play a role in the effects of anisomycin on v-Src levels and activity, we treated the v-Src::luciferase-expressing cells with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 alone and in combination with anisomycin. As shown in Fig. 6, 10 μM SB203580 reduced v-Src::luciferase levels and activity by itself and, when used in combination with anisomycin, blocked the anisomycin-induced increase in v-Src::luciferase levels and activity in both the NP-40 soluble and insoluble fractions. Similar results were obtained upon BIRB-796 treatment, another unrelated p38 inhibitor (not shown). However, RNAi-mediated knockdown of p38a led to a reduction in v-Src::luciferase protein levels upon p38 knockdown. In contrast, when v-Src::luciferase mRNA levels were examined by RT-PCR, a consistent decrease in mRNA levels was not observed, unlike the case for the v-Src::luciferase protein (not shown). We did not investigate the time dependence of the effects of p38 knockdown on v-Src::luciferase levels, which might have an impact on the observed response. In any case, these results suggest that effectors of p38 stress kinases could elicit context-dependent responses in this assay.

Fig. 6.

Immunoblot showing the p38 inhibitor SB203580 alters v-Src::luciferase levels and activity. Treatment of v-Src::luciferase cells with 0.1% DMSO (N), 1 µM geldanamycin (G), 1 µM geldanamycin and 10 µM SB203580 (G/S), 10 µM SB203580 (S), 50 ng/mL anisomycin (A), and 50 ng/mL anisomycin and 10 µM SB203580 for 24 h. NP-40 soluble or insoluble extracts analyzed for total phosphotyrosine, v-Src::luciferase, and actin levels

Effects of other cytotoxic agents

A bane of cell-based screens is the frequency of spurious hits caused by cytotoxic agents, a problem more pronounced with screens of extended duration. Since this assay is complete 3–6 h after the addition of compound, it was expected that false positives arising from such cytotoxic agents would be minimized. To test this assertion, we examined the effect of several cytotoxic agents in the v-Src::luciferase screen and in subsequent biochemical tests. Three general groups of agents were identified. Several agents (Fig. 7, top graph) had no effect on either v-Src::luciferase or native firefly luciferase activity. Another group (Fig. 7, middle graph) caused a selective reduction in v-Src::luciferase activity. The lower graph of Fig. 5 shows that treatment with paclitaxel increased v-Src::luciferase activity. Vinblastine, which as shown reduced v-Src::luciferase activity, increased this activity when used at lower concentrations, as was observed for anisomycin (not shown). The blot in the right panel indicates that representative members of each of these classes have little effect on Hsp70, protein ubiquitination, or phosphotyrosine levels at these concentrations. However, paclitaxel treatment at higher concentrations (see below), and sometimes at lower concentrations, did increase levels of v-Src::luciferase and phosphotyrosine without changing the levels of Hsp70. Paclitaxel was reported to increase expression of luciferase expressed from a CMV promoter, so these effects might result from transcriptional changes (Svensson et al. 2007).

Fig. 7.

Effect of 4-h treatment with various cytotoxic agents on luciferase activity in the v-Src::luciferase or native luciferase cell lines (left) and Hsp70, ubiquitin or total phosphotyrosine levels in the v-Src::luciferase line (right) after treatment with 3.2 µg/mL paclitaxel (P), 3.2 µg/mL vinblastine (V), 3.2 µg/mL gemcitabine (Gem), 0.1% DMSO (No), or 1 µg/mL geldanamycin (GA)

From these experiments, we expected that there would be a background of compounds that tested positive in the initial screen without affecting molecular chaperone or ubiquitin pathway function. In addition, compounds that affect regulation of the chaperone system could alter the luciferase readout. Secondary assays measuring independent clients such as Her2 or Bcr-Abl would be useful in these circumstances.

Mass screen

A compound library of 454,000 compounds was screened in the v-Src::luciferase HCT-116 tumor cell line. Several thousand compounds caused either a reduction or an increase in luciferase activity. The compounds that reduced luciferase activity were retested in a dose–response assay against both the v-Src::luciferase fusion line and against a line expressing native luciferase. Seventy-eight compounds selectively reduced v-Src::luciferase activity, although many of these compounds did have some effect on native luciferase activity.

Representative compounds from each chemical series were chosen, and these compounds were incubated with the v-Src::luciferase HCT-116 cells for 4 h. Two known compounds, geldanamycin (G) and the 20S proteasome inhibitor Velcade (V), also known as bortezumib or PS-341, were included as standards. Shown in Fig. 8a are immunoblots of a representative sample of the screening hits probed with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (PY), actin, and ubiquitin. Three compounds, 25, 33, and 34, reduced protein tyrosine phosphorylation and v-Src::luciferase protein levels while increasing inducible Hsp70 levels (the lower of the Hsp70 bands). Several compounds (10, 15, 27, 28, 29, and 31) increased protein ubiquitination, and in the case of 15, 29, and 31, well beyond that observed with Velcade. Compounds 26 and 30 caused a modest reduction in tyrosine phosphorylation and protein ubiquitination, but had a more pronounced effect on v-Src::luciferase levels.

Fig. 8.

Immunoblot examples of several compounds identified in the high-throughput screen analyzed for their effects on total phosphotyrosine, ubiquitin, v-Src::luciferase, or Her2 and Hsp70 levels. Cells were treated with the indicated compounds at 3.2 µg/mL except for N (0.1% DMSO), V (1 µg/mL bortezimib), or G (1 µg/mL geldanmycin). a Blots of v-Src::luciferase screening cell line extracts. b Blots of BT474 cell extracts

Several compounds were examined further in the Her2 overexpressing breast tumor line BT474 (Fig. 8b). As expected, geldanamycin treatment depleted Her2. Of the unknown compounds, 25 greatly decreased Her2 levels, while 26 and to a lesser extent 30 had a more modest effect. Darker exposures revealed high-molecular-weight bands reacting with the Her2 antibody in extracts from cells treated with 15, 29, and 31. We then immunoprecipitated Her2 from these extracts and found that Her2 ubiquitination increased upon treatment with geldanamycin and was further increased by co-treatment with lactacystin or compounds 15, 29, and 31 (not shown). A buildup of ubiquitinated proteins was also observed upon treatment with 15, 29, and 31 in HCT-116 v-Src::luciferase cells. Several compounds were also tested in the T cell leukemia line HSB2 which expresses activated Lck (Wright et al. 1994). Compounds 15, 29, and 31 again caused smearing on the phosphotyrosine blots, along with compound 22, while 25, 33, and 34 reduced total PY levels (data not shown). While compounds 33 and 34 did not appreciably deplete Her2 levels at the concentration tested, they did increase inducible Hsp70 levels, similar to geldanamycin and compound 25.

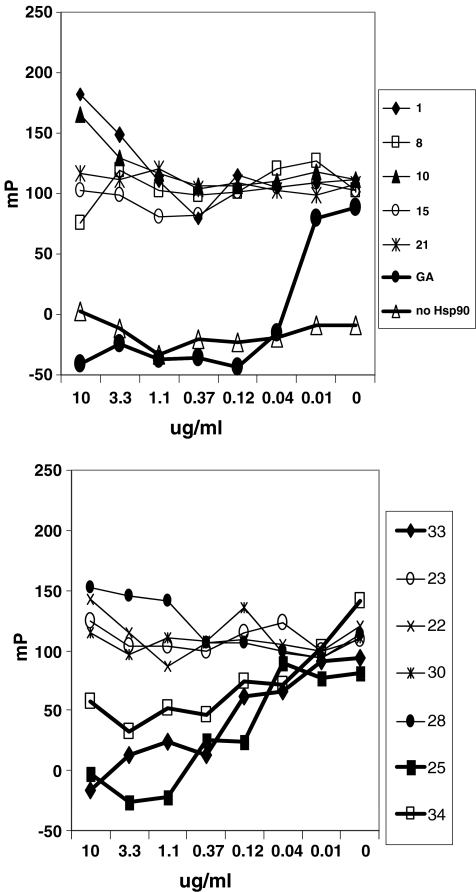

The hits from the screen were tested in an Hsp90 binding assay similar to that described by Kim et al. (2004). A representative group is shown in Fig. 9. In the left panel, the ability of geldanamycin to displace the fluorescent bodipy-labeled geldanamycin is shown. The right panel of Fig. 9 shows that compounds 25, 33, and 34, which possessed properties consistent with an Hsp90 inhibitor in the cell-based biochemical assays, competed with bodipy-labeled geldanamycin. The other compounds were inactive. After these results were obtained, compound 34 was disclosed by Vernalis as an Hsp90 inhibitor. Further work (data not shown) indicated that the other two compounds were unstable in aqueous solution.

Fig. 9.

Identification of Hsp90α inhibitors with a fluorescence polarization binding assay. Purified full-length Hsp90a bound to bodipy-labeled geldanamycin was incubated with compounds identified in the screen for 3 h. Dose–response curves for representative compounds are shown

Protein synthesis inhibitors

Several screening hits were known protein synthesis inhibitors, including puromycin 21, anisomycin 17, emetine 11, and an emetine analog isocephaline 24. These compounds and the unknown screening hits were tested for their ability to inhibit protein synthesis in a pulse-chase tritiated methionine incorporation assay in HCT-116 v-Src::luciferase cells (Fig. 10). Besides the known protein synthesis inhibitors, compounds 26 and 30 were active in this assay. After these results were obtained, Zaarur et al. (2006) showed that natural products related to emetine attenuated the heat shock response.

Fig. 10.

Graphical representation of the identification of two protein synthesis inhibitors from the high-throughput screen via a radioactive methionine incorporation assay. Relative acid-precipitable counts from extracts of cells treated with compounds for 2 h prior to radioactive labeling are shown

Ubiquitin pathway inhibitors

Several compounds identified in the primary screen caused increased total protein ubiquitination. In addition, one compound active in the screen (10) was structurally related to the known 20S proteasome inhibitor MG132. Given these results, we then determined whether any of these compounds were active in a 20S proteasome assay (Biomol Quantizyme 20S Proteasome Assay). As indicated in Fig. 11, the known 20S proteasome inhibitor lactacystin was active, along with compound 10. None of the other compounds was active in this assay and thus affect the ubiquitin pathway in some other manner.

Fig. 11.

Effects of some high-throughput screen compounds at 1 and 10 μg/mL on the ability of purified human 20S proteasome to cleave a fluorgenic substrate. Lactacystin is included as a positive control

Compounds that increase luciferase activity in the v-Src::luciferase assay

Paclitaxel, as shown in Fig. 7, caused an increase in luciferase activity in v-Src::luciferase cells, a property also noted with known histone deacetlyase inhibitors and anisomycin. While the major thrust of the screen was the identification of compounds that reduced luciferase activity in the primary screen, compounds that increased luciferase activity constituted the largest group of hits with several hundred compounds in this class. Of this group, 240 compounds that increased luciferase activity >2.5-fold in the primary screen were retested at 5 and 24 h at 10, 5, and 2.5 μM. Over 180 compounds were active at one or more concentrations in these retests. Several retained this activity at 24 h.

To determine whether increased luciferase activity was accompanied by increased v-Src activity or increased levels of v-Src, we treated HCT-116 v-Src::luciferase cells with a subset of this class of compound for 5 h and analyzed blots for PY, v-Src::luciferase levels, and Hsp70 levels relative to actin. In the example shown in Fig. 12, two compounds, paclitaxel and compound 37, increased both v-Src levels and activity. Cisplatin and novobiocin, which bind the carboxyl terminal domain of Hsp90 (Itoh et al. 1999; Marcu et al. 2000), caused a small increase in v-Src::luciferase levels and activity. As expected, both emetine and geldanamycin decreased v-Src levels, and geldanamycin reduced v-Src activity. Only geldanamycin had an effect on Hsp70 levels. Triptolide, an inhibitor of the heat shock response (Westerheide et al. 2006), had little effect on v-Src levels and activity.

Fig. 12.

Immunoblot showing the effects of compounds that increase the luciferase activity of v-Src::luciferase on NP-40 soluble total phosphotyrosine, v-Src::luciferase, and Hsp70 levels. Compounds were incubated for 5 h. 1 0.1% DMSO, 2 100 μM Taxol, 3 100 μM cisplatin, 4 100 μM novobiocin, 5 3 μg/mL emetine, 6 10 μM Cpd 37, 7 1 μM Cpd 37, 8 1 μM triptolide, 9 1 μM geldanamycin

Hsp70 complex inhibitors

To determine if any Hsp70 inhibitors were represented in the screening hits, a luciferase refolding assay catalyzed by Hsp70 and Hsp40 was used. A representative set of compounds from the total hit set were tested at two different concentrations in this refolding assay as shown in Fig. 13. In this set, compound 9 inhibited luciferase activity in the refolding reaction, but did not inhibit the activity of native luciferase (data not shown). In a more complete dose–response study, an IC50 of 2 μg/mL was observed. We also examined this compound in a peptide binding assay and an ATP competition assay with Hsp70 (Kang et al. 2008; Williamson et al. 2009), but saw significant interference from compound fluorescence. We are therefore unable to conclude whether compound 9 inhibits Hsp70 directly.

Fig. 13.

Effect of selected compounds on the refolding of denatured luciferase by Hsp70 and Hsp40. Compounds at a final concentration of 5 and 10 μg/mL ATP and denatured luciferase were mixed with Hsp40 and Hsp70 for 3 h and then analyzed for luciferase activity as described in “Materials and methods”

Discussion

Screens for agents that alter protein folding and degradation in cells have been reported in recent years (Zaarur et al. 2006; Hardcastle et al. 2007; Dickey et al. 2005). The screen described here provides a straightforward primary assay for several classes of inhibitors, including Hsp90 inhibitors, translational inhibitors, ubiquitin pathway inhibitors, Hsp70/Hsp40 complex inhibitors, and histone deacetylase inhibitors. An attractive feature of this screen is its simplicity, with clearly defined routes to characterization of primary hits based on the behavior of known compounds. The assay is also quite suitable for use as a routine secondary assay in a drug discovery setting.

The v-Src tyrosine kinase has been extensively characterized as a molecular chaperone client with stringent requirements for chaperone activity. v-Src is also a relatively unstable protein, with reported half-lives in chick embryo fibroblasts of 2–8 h, depending on the particular v-src allele (Sefton et al. 1982). Thus, two outcomes for the screen, detection of Hsp90 inhibitors and protein synthesis inhibitors, were expected from the outset. On the other hand, while ubiquitination of v-Src has been reported, it was not obvious that ubiquitin pathway inhibitors would have a measurable effect in this assay.

Three additional classes of compounds were picked up as hits in the screen: histone deacetylase inhibitors, p38 activators, and microtubule inhibitors. The effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on v-Src::luciferase levels was a surprise, given the role of acetylation in regulating Hsp90 (Bali et al. 2005; Scroggins et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2008). The cytomegalovirus promoter may be a complicating factor in this study, given the ability of histone acetylation to influence expression from the CMV promoter (Chen et al. 1997). Paclitaxel also affects CMV promoter-driven expression (Svensson et al. 2007). Anisomycin-induction of p38 is a well-documented phenomenon, and p38 inhibitors can block the induction of CMV promoter by certain cytotoxic agents (Gould et al. 1995; Bruening et al. 1998; Svensson et al. 2007). Perhaps the most interesting feature of our observations is the reduction of “basal” levels of v-Src::luciferase by p38 inhibitor treatment. Since p38 activates both Hsp27 and casein kinase II, which itself activates Cdc37, it could be supposed that p38 activation is a prerequisite for high-level v-Src::luciferase expression. However, we did not observe any decrease in Bcr-Abl levels in K562 chronic myelogenous leukemia cells treated with p38 inhibitors despite Bcr-Abl being an Hsp90 client (Blagosklonny et al. 2001). It is possible that the use of the CMV promoter in the screen masked certain histone deacetylase or p38 inhibitors. If such inhibitors were the focus of a screen, an expression system not dependent on the CMV promoter would aid in deconvoluting the effects of a compound on the CMV promoter compared to its effects on v-Src::Luc itself.

Complete loss of function of the Hsp70 co-activator DnaJ protein Ydj1 in yeast resulted in reduced v-Src production, while a less severe mutation in Ydj1 stabilized v-Src in an inactive form (Kimura et al. 1995; Dey et al. 1996a). Thus, Hsp40/Hsp70 inhibitors or activators were also expected from the screen. The identification of a compound that reduced ATP-dependent refolding of luciferase by a mixture of Hsp70 and Hsp40 supports this assertion.

In conclusion, the v-Src::luciferase assay presented here will facilitate the study of cellular interactions between folding and degradation pathways. The screen provides a rapid, reliable route to the identification and classification of inhibitors of protein folding and degradation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 32.5 kb)

References

- Adams J, Palombella VJ, Sausville EA, Johnson J, Destree A, Lazarus DD, Maas J, Pien CS, Prakash S, Elliott PJ. Proteasome inhibitors: a novel class of potent and effective antitumor agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2615–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An WG, Schulte TW, Neckers LM. The heat shock protein 90 antagonist geldanamycin alters chaperone association with p210bcr-abl and v-src proteins before their degradation by the proteasome. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali P, Pranpat M, Bradner J, Balasis M, Fiskus W, Guo F, Rocha K, Kumaraswamy S, Boyapalle S, Atadja P, Seto E, Bhalla K. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26729–26734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV, Fojo T, Bhalla KN, Kim JS, Trepel JB, Figg WD, Rivera Y, Neckers LM. The Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin selectively sensitizes Bcr-Abl-expressing leukemia cells to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2001;15:1537–1543. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brough PA, Aherne W, Barril X, Borgognoni J, Boxall K, Cansfield JE, Cheung KM, Collins I, Davies NG, Drysdale MJ, Dymock B, Eccles SA, Finch H, Fink A, Hayes A, Howes R, Hubbard RE, James K, Jordan AM, Lockie A, Martins V, Massey A, Matthews TP, McDonald E, Northfield CJ, Pearl LH, Prodromou C, Ray S, Raynaud FI, Roughley SD, Sharp SY, Surgenor A, Walmsley DL, Webb P, Wood M, Workman P, Wright L. 4,5-Diarylisoxazole Hsp90 chaperone inhibitors: potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. J Med Chem. 2008;51:196–218. doi: 10.1021/jm701018h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruening W, Giasson B, Mushynski W, Durham HD. Activation of stress-activated MAP protein kinases up-regulates expression of transgenes driven by the cytomegalovirus immediate/early promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:486–489. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood SK, Khaleque MA, Sawyer DB, Ciocca DR. Heat shock proteins in cancer: chaperones of tumorigenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Nathan DF, Lindquist S. In vivo analysis of the Hsp90 cochaperone Sti1 (p60) Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:318–325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Bailey EC, McCune SL, Dong JY, Townes TM. Reactivation of silenced, virally transduced genes by inhibitors of histone deacetylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5798–5803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlmann B. Proteasomes. Essays Biochem. 2005;41:31–48. doi: 10.1042/EB0410031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B, Caplan AJ, Boschelli F. The Ydj1 molecular chaperone facilitates formation of active p60v-src in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:91–100. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B, Lightbody JJ, Boschelli F. CDC37 is required for p60v-src activity in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1405–1417. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey CA, Eriksen J, Kamal A, Burrows F, Kasibhatla S, Eckman CB, Hutton M, Petrucelli L. Development of a high throughput drug screening assay for the detection of changes in tau levels—proof of concept with HSP90 inhibitors. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:231–238. doi: 10.2174/1567205053585927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould GW, Cuenda A, Thomson FJ, Cohen P. The activation of distinct mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades is required for the stimulation of 2-deoxyglucose uptake by interleukin-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 in KB cells. Biochem J. 1995;311(Pt 3):735–738. doi: 10.1042/bj3110735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Rocha K, Bali P, Pranpat M, Fiskus W, Boyapalle S, Kumaraswamy S, Balasis M, Greedy B, Armitage ES, Lawrence N, Bhalla K. Abrogation of heat shock protein 70 induction as a strategy to increase antileukemia activity of heat shock protein 90 inhibitor 17-allylamino-demethoxy geldanamycin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10536–10544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle A, Tomlin P, Norris C, Richards J, Cordwell M, Boxall K, Rowlands M, Jones K, Collins I, McDonald E, Workman P, Aherne W. A duplexed phenotypic screen for the simultaneous detection of inhibitors of the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 and modulators of cellular acetylation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1112–1122. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Brott BK, Leon JH, Perdew GH, Jove R, Pratt WB. Reconstitution of the multiprotein complex of pp 60src, hsp90, and p50 in a cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2902–2908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Ogura M, Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Miura AB, Tashima Y. A novel chaperone-activity-reducing mechanism of the 90-kDa molecular chaperone HSP90. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 3):697–703. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3430697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MR, Schoepfer J, Radimerski T, Massey A, Guy CT, Brueggen J, Quadt C, Buckler A, Cozens R, Drysdale MJ, Garcia-Echeverria C, Chene P. NVP-AUY922: a small molecule HSP90 inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical breast cancer models. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R33. doi: 10.1186/bcr1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RC, Farrell AT, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. United States Food and Drug Administration approval summary: bortezomib for the treatment of progressive multiple myeloma after one prior therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2955–2960. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Taldone T, Clement CC, Fewell SW, Aguirre J, Brodsky JL, Chiosis G. Design of a fluorescence polarization assay platform for the study of human Hsp70. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3749–3751. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasibhatla SR, Hong K, Biamonte MA, Busch DJ, Karjian PL, Sensintaffar JL, Kamal A, Lough RE, Brekken J, Lundgren K, Grecko R, Timony GA, Ran Y, Mansfield R, Fritz LC, Ulm E, Burrows FJ, Boehm MF. Rationally designed high-affinity 2-amino-6-halopurine heat shock protein 90 inhibitors that exhibit potent antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2767–2778. doi: 10.1021/jm050752+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Felts S, Llauger L, He H, Huezo H, Rosen N, Chiosis G. Development of a fluorescence polarization assay for the molecular chaperone Hsp90. J Biomol Screen. 2004;9:375–381. doi: 10.1177/1087057104265995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Yahara I, Lindquist S. Role of the protein chaperone YDJ1 in establishing Hsp90-mediated signal transduction pathways. Science. 1995;268:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.7761857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Rutherford SL, Miyata Y, Yahara I, Freeman BC, Yue L, Morimoto RI, Lindquist S. Cdc37 is a molecular chaperone with specific functions in signal transduction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1775–1785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs JJ, Murphy PJ, Gaillard S, Zhao X, Wu JT, Nicchitta CV, Yoshida M, Toft DO, Pratt WB, Yao TP. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell. 2005;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz GP, Lin H, Harst A, Obermann WM. Aha1 binds to the middle domain of Hsp90, contributes to client protein activation, and stimulates the ATPase activity of the molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17228–17235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu MG, Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Catelli M, Neckers LM. The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37181–37186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AJ, Tam S, Kaganovich D, Frydman J. Protein quality control: chaperones culling corrupt conformations. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:736–741. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum AK, Teneyck CJ, Sauer BM, Toft DO, Erlichman C. Up-regulation of heat shock protein 27 induces resistance to 17-allylamino-demethoxygeldanamycin through a glutathione-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10967–10975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough H, Patterson C. CHIP: a link between the chaperone and proteasome systems. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:303–308. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0303:CALBTC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimnaugh EG, Xu W, Vos M, Yuan X, Isaacs JS, Bisht KS, Gius D, Neckers L. Simultaneous inhibition of hsp 90 and the proteasome promotes protein ubiquitination, causes endoplasmic reticulum-derived cytosolic vacuolization, and enhances antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:551–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata Y. Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin and its derivatives as novel cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1131–1138. doi: 10.2174/1381612053507585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PJ, Morishima Y, Kovacs JJ, Yao TP, Pratt WB. Regulation of the dynamics of hsp90 action on the glucocorticoid receptor by acetylation/deacetylation of the chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33792–33799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MV, Clarke PA, Workman P. Dual targeting of HSC70 and HSP72 inhibits HSP90 function and induces tumor-specific apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao R, Fiskus W, Yang Y, Lee P, Joshi R, Fernandez P, Mandawat A, Atadja P, Bradner JE, Bhalla K. HDAC6 inhibition enhances 17-AAG-mediated abrogation of hsp90 chaperone function in human leukemia cells. Blood. 2008;112:1886–1893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggins BT, Robzyk K, Wang D, Marcu MG, Tsutsumi S, Beebe K, Cotter RJ, Felts S, Toft D, Karnitz L, Rosen N, Neckers L. An acetylation site in the middle domain of Hsp90 regulates chaperone function. Mol Cell. 2007;25:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefton BM, Patschinsky T, Berdot C, Hunter T, Elliott T. Phosphorylation and metabolism of the transforming protein of Rous sarcoma virus. J Virol. 1982;41:813–820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.3.813-820.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S, Workman P. Inhibitors of the HSP90 molecular chaperone: current status. Adv Cancer Res. 2006;95:323–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp SY, Boxall K, Rowlands M, Prodromou C, Roe SM, Maloney A, Powers M, Clarke PA, Box G, Sanderson S, Patterson L, Matthews TP, Cheung KM, Ball K, Hayes A, Raynaud F, Marais R, Pearl L, Eccles S, Aherne W, McDonald E, Workman P. In vitro biological characterization of a novel, synthetic diaryl pyrazole resorcinol class of heat shock protein 90 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2206–2216. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solit DB, Rosen N. Hsp90: a novel target for cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1205–1214. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RU, Barnes JM, Rokhlin OW, Cohen MB, Henry MD. Chemotherapeutic agents up-regulate the cytomegalovirus promoter: implications for bioluminescence imaging of tumor response to therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10445–10454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taldone T, Gozman A, Maharaj R, Chiosis G. Targeting Hsp90: small-molecule inhibitors and their clinical development. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler PA, Boschelli F. Src homology 2 domain deletion mutants of p60v-src do not phosphorylate cellular proteins of 120–150 kDa. Oncogene. 1989;4:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerheide SD, Kawahara TL, Orton K, Morimoto RI. Triptolide, an inhibitor of the human heat shock response that enhances stress-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9616–9622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DS, Borgognoni J, Clay A, Daniels Z, Dokurno P, Drysdale MJ, Foloppe N, Francis GL, Graham CJ, Howes R, Macias AT, Murray JB, Parsons R, Shaw T, Surgenor AE, Terry L, Wang Y, Wood M, Massey AJ. Novel adenosine-derived inhibitors of 70 kDa heat shock protein, discovered through structure-based design. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1510–1513. doi: 10.1021/jm801627a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:202–216. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DD, Sefton BM, Kamps MP. Oncogenic activation of the Lck protein accompanies translocation of the LCK gene in the human HSB2 T-cell leukemia. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2429–2437. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Lindquist S. Heat-shock protein hsp90 governs the activity of pp 60v-src kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7074–7078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaarur N, Gabai VL, Porco JA, Jr, Calderwood S, Sherman MY. Targeting heat shock response to sensitize cancer cells to proteasome and Hsp90 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1783–1791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 32.5 kb)