Because acute cough has a different range of causes in adults than it does in children, adults should be assessed and treated differently. The American College of Chest Physicians’ evidence-based clinical practice guidelines1 recommend that patients with acute cough be divided into children (younger than 15 years of age) and adults (15 years of age or older). Also, people with underlying and chronic diseases or compromised immune systems should be considered and treated differently; primary care clinicians will have no difficulty recognizing such patients.

Mr John Smith, a 37-year-old taxi driver, comes to see you on Thursday evening as a drop-in patient. He complains of a cough that has been bothering him for 9 days. He felt a bit shivery when it began, but that has passed. The cough is worse at night but it is also present during the day. He is coughing up slight amounts of yellow-green sputum, once with a slight streak of blood. He feels slightly under the weather because the cough is hindering his sleep.

During the past 5 years, you have seen him 3 times. Once he had an ingrown toenail, once he had an acute back strain (helping a passenger unload at the airport), and once he had tonsillitis. He is not currently taking any medication and has no chronic diseases. His patient record mentions that he is a smoker.

Epidemiology and population at risk

Acute cough is one of the most common presentations in general practice. This type of cough, also described as acute bronchitis, is the fifth most common new presentation to FPs in Australia2 and the United States.3 Figures from the United Kingdom suggest there are about 50 cases per 1000 people each year,4 and acute cough leads to 10 ambulatory visits per 1000 visits each year in the United States.5 Evidence from such general practice reports and the US and UK morbidity surveys shows that the overwhelming majority of acute coughs are infectious in origin.

Mr Smith’s story suggests an acute respiratory tract infection. He has no risk factors for serious respiratory disease, although you note he is a smoker and you do not know whether he has asthma. His job entails long hours in a confined space with many different people, which would certainly increase his risk of picking up an infection.

You question him further.

What else could it be?

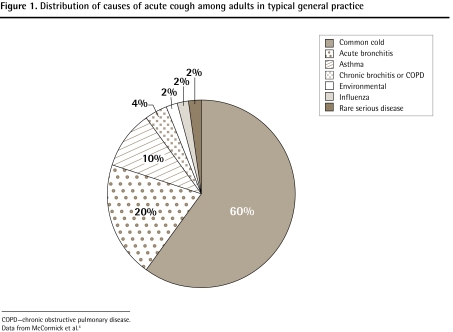

Figure 1 shows the distribution of cough causes in typical general practice.4

Figure 1.

Distribution of causes of acute cough among adults in typical general practice

COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Data from McCormick et al.4

Mr Smith says he does not, as far as he knows, have asthma or any heart troubles. Although he has smoked for 20 years, he felt fine until 9 days ago; he has not noticed any weight loss, chest pain, or hemoptysis. Because recent Health Canada regulations have prohibited smoking in the taxi, he has actually reduced his daily cigarette consumption from 20 to about 10. He has not felt short of breath. The illness came on slowly, over a day or so. He has not traveled out of town for 2 years.

Alarm symptoms

The patient might report a sudden fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]) or might have been in contact with an infected person (eg, influenza, SARS). He or she will remember recent air travel or surgical procedures (eg, pulmonary embolism), or being exposed to an unusual respiratory irritant (eg, chemicals, gases, excessive tobacco smoke). The patient will usually remember wheezing. The doctor will know whether the patient is immunosuppressed or suffers from asthma or dementia.

Alarm signs

The patient will seem unusually ill (eg, pneumonia, influenza) or short of breath (eg, congestive heart failure, SARS, acute asthma). There might be a high fever (eg, SARS, pneumonia, influenza). The respiratory rate might be increased. There might be signs of reduced air entry, consolidation, or restricted air entry.

Mr Smith looks slightly tired but otherwise well. He coughs once into a tissue while in your office; a small amount of yellowish sputum appears on the tissue. His temperature is 37.0°C, his pulse is 82 beats/min, and his respiratory rate is 17 breaths/min. Ears, nose, and throat examination findings are normal; no cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy is present. There is good air entry into all zones of his lungs. You hear 1 or 2 faint crackles on inspiration; these disappear when he coughs. You have not heard of any outbreaks of influenza or other respiratory disease in your area.

You are becoming almost certain that he has acute bronchitis.

How sure of the diagnosis are you?

Acute bronchitis is usually a presumptive diagnosis, which is made based on history and examination, when the patient presents with an acute productive cough of less than 3 weeks’ duration. However, most GPs are worried that they might miss a case of acute community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), which still has relatively high mortality, especially among the elderly.6 The criterion standard for diagnosing CAP is the presence of consolidation on the chest radiograph, but GPs cannot be ordering chest x-ray scans for every patient with acute cough.

As no one symptom or sign has a large effect of the likelihood of pneumonia being present in a person with an acute cough, investigators have combined various symptoms and signs to make clinical decision rules for CAP7–9; unfortunately, even if a patient without asthma has fever, tachycardia, and crackles—a combination of symptoms and signs very suggestive of pneumonia—the rules still do not have enough power to definitively “rule in” pneumonia. They do, however, certainly suggest a chest x-ray scan should be done.

The American College of Chest Physicians1 recommends that absence of the following findings reduces the likelihood of pneumonia sufficiently to eliminate the need for a chest x-ray scan:

heart rate greater than 100 beats/min;

respiratory rate greater than 24 breaths/min;

oral temperature greater than 38°C; and

chest examination showing focal consolidation, egophony, or fremitus.

Similarly, when the history is suggestive of acute bronchitis and there are no alarm signs in the chest, there is no need for sputum analysis, viral culture, or serologic analysis.

Table 1 shows positive and negative likelihood ratios for pneumonia of various respiratory symptoms and physical signs.10 Note that, apart from egophony, neither symptoms nor signs have high positive likelihood ratios for pneumonia; in a low-prevalence primary care situation, the positive likelihood ratio has to be very high to significantly increase the chances of pneumonia being present. Similarly, apart from a previous history of asthma and a currently runny nose, few symptoms or signs have much of a negative likelihood ratio.

Table 1.

Likelihood ratios for pneumonia of various respiratory symptoms and physical signs

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | POSITIVE LIKELIHOOD RATIO | NEGATIVE LIKELIHOOD RATIO |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory symptoms | ||

| • Cough | 1.8 | 0.3 |

| • Dyspnea | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| • Sputum produced | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| Other symptoms | ||

| • Fever | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| • Chills | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| • Myalgia | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| • Sore throat | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| • Runny nose | 0.8 | 2.4 |

| Medical history | ||

| • Asthma | 0.1 | 3.8 |

| • Immunosuppression | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| • Dementia | 3.4 | 0.9 |

| Vital signs | ||

| • Tachypnea > 25 breaths/min | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| • Temperature > 37.8°C | 4.4 | 0.7 |

| Chest signs | ||

| • Dull percussion | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| • Decreased sounds | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| • Crackles | 2.7 | 0.8 |

| • Bronchial sounds | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| • Egophony | 8.6 | 1.0 |

Data from Metlay et al.10

You decide that the absence of alarm symptoms and signs, together with the absence of any features that would increase the possibility of pneumonia, confirm your diagnosis of acute bronchitis.

Is it likely to get worse?

Acute bronchitis is an infection of the tracheo-bronchial tree, which might transiently produce sputum and symptoms of airway obstruction. The cough commonly lasts 7 to 10 days, but can last up to 1 month in 25% of patients.11 When the clinical course of control-group patients in trials of antibiotic treatment of acute bronchitis was studied, it was found that 85% to 90% of patients improved spontaneously, just as quickly as if they had not taken antibiotics.12

Deciding on best treatment

Reports have shown that up to 80% of non-smokers and 90% of smokers with acute bronchitis receive antibiotics.13,14 There have been a number of reviews of the effects of antibiotics on the course of acute bronchitis. Half of them concluded that there was no benefit from taking antibiotics; the other half, including a Cochrane review, concluded that antibiotics can have some modest treatment effects compared with placebo.15 The use of antibiotics decreases the time feeling ill with cough and sputum production by about half a day, and reduces time lost from work by about a third of a day. These modest benefits, which might occur only in a subgroup of patients, must be weighed against the chance of antibiotic side effects.

You explain to Mr Smith that there is no sign of serious illness; he has acute bronchitis due to a viral infection. The condition is like a “cold on the chest” and it will get better by itself; there is no need for antibiotic treatment. It should take about 2 weeks to get better.

Mr Smith accepts your diagnostic explanation, but explains that the cough at night is preventing good sleep, and he does not wish to miss work because of the illness. Surely there is some medicine to relieve his illness?

Most adults who present to their FPs with cough are looking for relief of their symptoms.16 Unless the patient has a history of asthma, or the clinician can hear widespread wheezing, β-agonists are not recommended.17 There is no evidence that mucolytics help in acute bronchitis. Although cough suppressants and antihistamines have not specifically been well studied in patients with acute bronchitis, the former can be effective in chronic bronchitis and the latter provide some relief for patients with colds. It seems reasonable that a combined cough suppressant and antihistamine might provide short-term symptomatic relief in a patient with acute bronchitis.

Your careful history has excluded any likely serious causes for Mr Smith’s acute cough; in particular, your careful clinical examination has ruled out asthma and CAP. You are certain that his recent-onset productive cough is due to acute bronchitis. He accepts your explanation that antibiotics will be of no use, and you have suggested a short-term cough suppressant and antihistamine to relieve his annoying symptoms so that he can continue working.

You remind Mr Smith to try (once again) to give up smoking. You recommend that Mr Smith use an over-the-counter medication (dextromethorphan, with or without an antihistamine) at night for the next 7 to 10 days. You recommend that he return to see you if he gets worse, or does not improve, at the end of that time period.

You make a mental note to consider a chest x-ray scan if his cough persists, he loses weight, or he remains unwell.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, Boulet LP, Braman SS, Brightling CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):1S–23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meza RA, Bridges-Webb C, Sayer GP, Miles DA, Traynor V, Neary S. The management of acute bronchitis in general practice: results from the Australian Morbidity and Treatment Survey, 1990–1991. Aust Fam Physician. 1994;23(8):1550–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delozier JE, Gagnon RO. National ambulatory care survey: advance data. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1991. Publication no. 203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick A, Fleming D, Charlton C. Morbidity statistics from general practice—fourth National Morbidity Survey, 1991–92. London, UK: HMSO, Office for National Statistics; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Center for National Health Statistics . Data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1999. Atlanta, GA: US Center for National Health Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diehr P, Wood RW, Bushyhead J, Krueger L, Wolcott B, Tompkins RK. Prediction of pneumonia in outpatients with acute cough—a statistical approach. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(3):215–25. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal BM, Hedges JR, Radack KL. Decision rules and clinical prediction of pneumonia: evaluation of low-yield criteria. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, Mutha SS, Sankey SS, Weissfeld LA, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275(2):134–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckerling PS, Tape TG, Wigton RS, Hissong KK, Leikin JB, Ornato JP, et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(9):664–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-9-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metlay JP, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ. Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hueston WJ, Mainous WG., 3rd Acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(6):1270–6. 1781–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alberta Clinical Guidelines Program . Guideline for the management and treatment of acute bronchitis. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Clinical Guidelines Program; 2000. Available from: www.albertadoctors.org. Accessed 2010 Nov 26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stocks NP, Fahey T. The treatment of acute bronchitis by general practitioners in the UK. Results of a cross-sectional postal survey. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(7):676–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linder JA, Sim I. Antibiotic treatment of acute bronchitis in smokers: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):230–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SM, Fahey T, Smucny J, Becker LA. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD000245. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000245.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzales R, Barrett PH, Jr, Crane LA, Steiner JF. Factors associated with antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):541–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smucny J, Becker LA, Glazier R. Beta2-agonists for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001726. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001726.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]