Abstract

The phenotype produced by a given genotype can be strongly modulated by environmental conditions. Therefore, natural populations continuously adapt to environment heterogeneity to maintain optimal phenotypes. It generates a high genetic variation in environment-sensitive gene networks, which is thought to facilitate evolution. Here we analyze the chromatin regulator crm, identified as a candidate for adaptation of Drosophila melanogaster to northern latitudes. We show that crm contributes to environmental canalization. In particular, crm modulates the effect of temperature on a genomic region encoding Hedgehog and Wingless signaling effectors. crm affects this region through both constitutive heterochromatin and Polycomb silencing. Furthermore, we show that crm European and African natural variants shift the reaction norms of plastic traits. Interestingly, traits modulated by crm natural variants can differ markedly between Drosophila species, suggesting that temperature adaptation facilitates their evolution.

Author Summary

The fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster was initially endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and started to colonize Europe and Asia around 10,000 years ago. Northern populations have adapted to these colder environments and differ from Sub-Saharan populations for temperature sensitive traits. Here we analyze cramped (crm), a gene previously identified as a putative target of adaptive selection during the colonization of northern latitudes. crm is involved in the regulation of chromosome structure, a process known to be strongly modulated by temperature. We show that crm is limiting for distinct processes at different temperatures and that crm natural variation modulates temperature sensitive phenotypes. Our results suggest that environmental heterogeneity maintains functional variation in environment sensitive gene networks and might facilitate evolution.

Introduction

Environmental conditions can strongly modulate the phenotypes produced by particular genotypes (phenotypic plasticity). Recent studies have stressed how important it is to take into account genetic variation and environmental conditions to analyze the properties of gene regulatory networks [1], [2]. Indeed gene regulatory networks have been selected to cope with variable genetic backgrounds and environmental conditions. This explains, for example, the redundancy of particular regulatory sequences [3], [4]. Selection can limit the influence of the environment (environmental canalization) [5] or compensate it so that different genotypes maintain the same phenotype in different environments (genetic compensation) [6]. Alternatively, the influence of the environment can be selected for so that the different phenotypes produced in distinct environments by a given genotype are optimal in each environment (adaptive phenotypic plasticity) [7]. The spatial and temporal heterogeneity of environmental conditions leads to continuous adaptation of natural populations. It maintains a high genetic variation in environment sensitive gene networks, which can be easily revealed in artificial selection experiments [5], [8], [9]. This high genetic variation is thought to facilitate evolution. These ideas are actively discussed [10]–[12], but experiments analyzing the effect of variation in individual genes in different environmental conditions are required to test them.

We analyze here a candidate gene for adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. This species was initially endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and started to colonize the rest of the world around 10,000 years ago. Sub-Saharan and European populations now differ dramatically for temperature sensitive traits (such as ovariole number, pigmentation, size, and cold resistance) [13]–[15], indicating that flies have adapted to these new, partially colder, environments. A region of the X chromosome containing the gene cramped (crm) was identified as being putatively involved in adaptation to northern latitudes [16]. crm is involved in Polycomb silencing and position effect variegation (PEV) [17]. These two processes, linked to chromatin regulation, are known to be strongly modulated by temperature [18]. Here, we investigate the involvement of crm in thermal plasticity and whether crm natural variation could have contributed to the adaptation of Drosophila populations to environmental temperature.

Results

CRM molecular variation and divergence

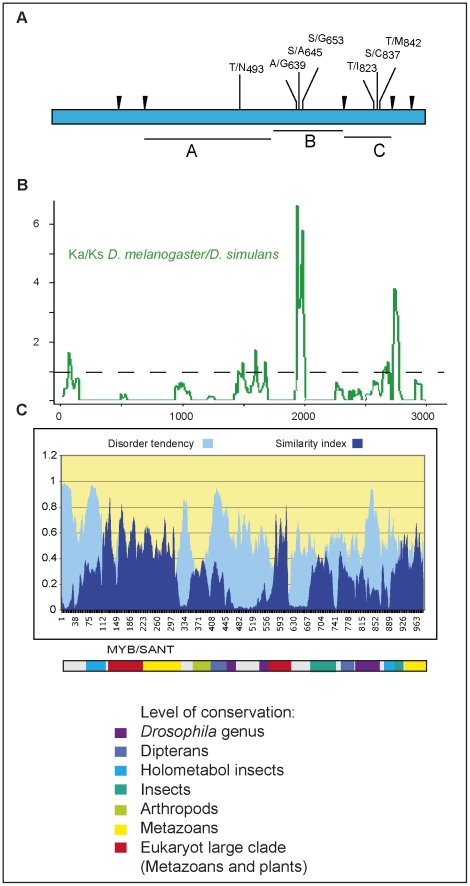

In natural D. melanogaster populations, apart from rare amino acid polymorphisms segregating in some African alleles only, amino acid polymorphisms are observed in three regions (A, B, C) in the C-terminal half of CRM [16] (Figure 1A). Analysis of the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks), when compared to the CRM homologue of the closely related species D. simulans using a sliding window (Figure 1B) suggests that recurrent selection is driving amino acid replacements in these regions. These rapidly evolving regions are located between conserved domains, and are predicted to be intrinsically disordered [19] (Figure 1C). Disordered domains are natively unfolded. They are frequently found in transcription factors and are thought to facilitate protein complex formation. They often carry post-translational modifications modulating protein interactions and stability [20], [21]. The geographic partitioning of variation in D. melanogaster strongly suggests that natural selection has recently shaped the distribution of CRM variants during and after the out of Africa expansion: the derived mutations A639G and T842M are absent in the African sample but found at high frequency in Europe (Text S1; Figure S1, Figure S2).

Figure 1. Amino acid polymorphisms in CRAMPED.

A: Structure of CRM product in Drosophila melanogaster. Intron positions are indicated as inverted black triangles. Several amino acid polymorphisms are observed in the C-terminal half. They cluster in three regions that we named A, B and C. B: Ka/Ks ratio of CRM calculated using the 35 D. melanogaster sequences and D. simulans crm homologue and analyzed with a sliding window. The amino acid polymorphisms observed in D. melanogaster are located in rapidly evolving regions with Ka/Ks>1, indicating positive selection. C: identification of conserved domains in CRM using alignments with homologues from various species. The percentage of similarity is represented in dark blue. The color code indicates the level of conservation. A MYB/SANT domain is conserved with plant homologues [25]. MYB domains are DNA binding domains, but the related SANT domains are frequently observed in proteins interacting with histones [65]. Disorder tendency is represented in light blue.

Altogether the patterns of coding variation and divergence in crm suggest that spatially varying selection favors particular amino acid replacements and leads to the rapid evolution of specific domains. We first sought to identify processes particularly sensitive to crm in controlled temperature conditions in order to test later how crm natural variants affect these processes.

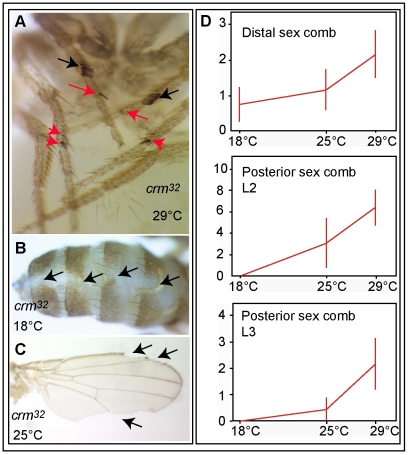

CRM buffers distinct processes at low and high temperature

Processes particularly sensitive to crm can be identified by the aberrant phenotypes observed in crm mutants. We analyzed the phenotypes of crm mutants at different temperatures using a null allele, crm32. The phenotypes observed with the crm32 allele at different temperatures are caused by this allele and not by another mutation in the genome because they are not observed when a crm genomic rescue construct is present in the genome (see below). Wild type Drosophila melanogaster males have a single sex comb located on the first tarsal segment of each prothoracic leg. crm null mutant males, however, display ectopic sex combs, both distally on the prothoracic leg and on more posterior legs [17] (Figure 2A). Posterior sex combs represent the canonical Polycomb phenotype, caused by a defect in the repression of the homeotic gene Sex comb reduced (Scr) [22]. We observed that both ectopic sex comb phenotypes are increased at higher temperatures (Figure 2D: N = 10 for each temperature point), as previously described with another crm allele, crm7 [17], [23]. Conversely, other mutant phenotypes (abdominal dorsal fusion defects and wing margin defects) are enhanced at lower temperatures (Figure 2B, 2C). This is most obvious for the dorsal fusion defects, which are observed at 18°C but not at 25°C or 29°C. These experiments indicate that crm is involved in at least two distinct processes, and that its ability to buffer these processes is differentially required at low or high temperatures.

Figure 2. crm is limiting for distinct processes at low and high temperature.

Analysis with the null mutant crm32 of crm limiting roles on development at different temperatures (A–C). Morphological defects observed in crm mutants are temperature sensitive: ectopic sex combs (up, red arrows) are enhanced at high temperature (A) whereas abdominal dorsal fusion (middle, arrows) are observed only at low temperature (B). Wing margin defects (bottom, arrows) are enhanced at low temperature (C). The wing is from a hemyzygote escapers that can occasionally be obtained at 25°C. D: quantification of ectopic sex comb teeth (+/−1 standard deviation) in crm32 mutants at 18, 25 and 29°C in the distal sex comb on the second tarsal segment of the first leg, posterior sex comb on the second leg (L2) and the third leg (L3).

Two additional pieces of evidence demonstrate the pleiotropic nature of crm. First, the different phenotypes found in crm mutants can be enhanced by mutations in different chromatin regulators. For example, the ectopic posterior sex comb phenotype can be enhanced by mutations in Polycomb Group genes (PcG) such as Polycomb-like (Pcl) (Figure S3). The distal sex comb phenotype was shown previously to be dramatically enhanced by heterozygosity for a null allele of the transcription factor bric-à-brac (bab) [23]. In contrast, the ectopic sex comb phenotypes are decreased and the dorsal fusion defects are enhanced by mutations in Su(var)3-9, required for the formation of centromeric heterochromatin [24] (Figure S3). Indeed, dorsal fusion defects are visible at 25°C in crm32; Su(var)3917 males, and are not observed in Su(var)3917 males. Second, deletions of different conserved domains in CRM, affect different phenotypic read-outs. Indeed, it is possible to find CRM homologues in organisms as distantly related as plants [25] and to identify several conserved domains, labeled I to VII (Figure 1C, Figure S4). We generated transgenes allowing the conditional expression of mutant forms with deletions of particular conserved domains (Figure S4). We observed that several of them behave as dominant negatives. Although these types of mutants are very artificial and may induce defects difficult to interpret, they represent a way to disturb the network in vivo from inside as these truncated forms are able to interact with some cofactors, but not with others. In our case, this approach turned out to be very informative as the dominant mutants differently affect the processes sensitive to crm loss of function at low or high temperature: ubiquitous expression of CRM mutant forms with deletion of domain II or VI induces the formation of ectopic sex combs (both distal and posterior) (Figure S4B, S4C). Ubiquitous expression of a mutant form with a deletion of domain V leads to dorsal fusion defects (Figure S4B), and when expressed in the wing imaginal disc using the bi/omb-Gal4 driver, induces a strong wing growth defect (Figure S4E). Furthermore, the expression of this del-V dominant mutant in the dorsal region using the driver Pnr-Gal4 increases thoracic and abdominal pigmentation (Figure S4D). In contrast, it induces much more weakly ectopic sex combs. In conclusion, CRM is a highly pleiotropic protein with a modular structure. Furthermore, at particular temperatures (cold/hot), CRM is limiting for distinct processes (dorsal fusion/posterior sex comb restriction) through interactions involving different domains (V/II, VI) and different factors (Su(var)3.9/Pcl).

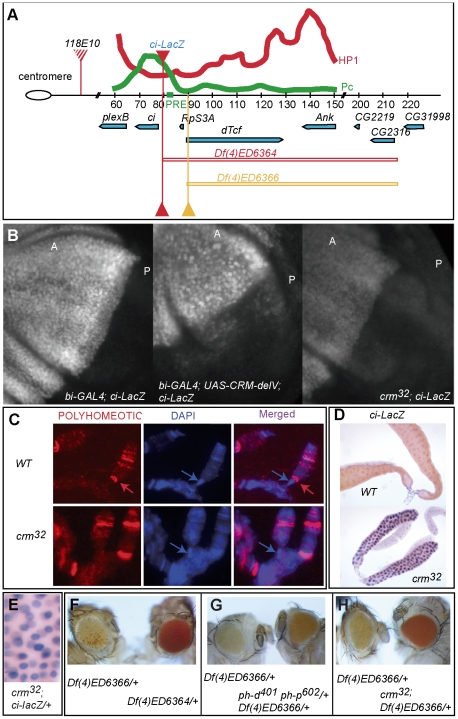

crm is required for the PcG silencing of cubitus interruptus

We used the strong phenotypes induced by the crm dominant negative crm-del-V to identify genes particularly sensitive to crm disruption. By testing genetically several genes involved in wing development we identified cubitus interruptus (ci) encoding the effector of the Hedgehog signaling pathway as interacting with crm. We tested whether ci is mis-regulated in crm mutants using the LacZ enhancer trap inserted in ci (Figure 3A). In the wing disc, ci is spatially regulated. It is expressed in the anterior compartment and repressed in the posterior compartment. We observed that driving the expression of a CRM-del-V dominant negative in the wing disc leads to an ectopic expression of ci-LacZ in the posterior compartment (Figure 3B). To confirm the relevance of this finding, we also tested crm LOF mutants. Loss of crm function also leads to ectopic (though weaker) ci expression in the posterior compartment (Figure 3B). Interestingly, ci-LacZ expression is also reduced in the anterior compartment in crm null mutants (Figure 3B), suggesting that crm is required for both repression and activation of ci in the wing disc.

Figure 3. crm is required for the Polycomb silencing of cubitus interuptus.

A: drawing of the cubitus interuptus (ci) genomic region. ci is located on the proximal part of the fourth chromosome around 70Kb from the chromocenter. Four P-element insertions used in this study are represented (118E-10, ci-LacZ, df(4)ED6364, and df(4)ED6366) [27], [66], [67], [68]. A Polycomb response element identified in ci [26] is indicated as a green rectangle. The relative levels of HP1 and Polycomb in the ci region are redrawn from the study of de Wit et al. (2007) in Kc cells using DamID fusion. B: Immunodetection of ci-LacZ in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs of a bi-GAL4 control, bi-GAL4; UAS-CRM-del-V (dominant mutant) and crm32 (null mutant). Magnification 40×, exposure time: 455ms. A: anterior compartment; B: Posterior compartment. C: Immunodetection of the Polycomb group protein Polyhomeotic (PH) on salivary gland polytene chromosomes of WT and crm32 larvae. PH binds ci (red arrow) located close to the fourth chromosome chromocenter (blue arrow) as previously described [26]. In crm mutants the PH binding on ci is no longer visible whereas other binding sites on the fourth chromosome remain. D: ci-LacZ is de-repressed in salivary glands of crm32 mutants. E: higher magnification of salivary glands of crm32; ci-LacZ stained for LacZ. A strong stockasticity is observed. F: The lines Df(4)ED6364 and Df(4)ED6366 which differ in the absence or presence of the ci-tcf intergene region have markedly different white expression. These two deficiencies have the same distal break, but differ in their proximal extension. Def(4)ED6364 deletes ci PRE, whereas Def(4)ED6366 keeps it intact (A). Both deletions carry a functional white gene inserted in the deleted region in the same orientation [27]. G: In ph-d401 ph-p602/+ femelles the expression of white inserted in the trangene Df(4)ED6366 is increased. H: When placed in a crm32 background the expression of white inserted in the trangene Df(4)ED6366 is even more increased.

The PcG protein Polyhomeotic (PH) has been shown to repress ci directly [26]. Accordingly, in salivary gland nuclei, where ci is repressed, the PH protein is bound to the ci locus [26]. We therefore tested whether crm is required for PH binding to the ci locus, by comparing PH distribution in crm null mutant and wild type salivary glands. Interestingly, while most PH bands on salivary gland polytene chromosomes remain unchanged in crm mutants, the PH band at ci disappears (Figure 3C), suggesting a very specific role for crm in the regulation of ci. A role of crm in regulating ci is further demonstrated by the derepression of a ci-LacZ reporter gene in salivary glands of crm mutants (Figure 3D). Note that the ci-LacZ de-repression is stochastic as the intensity of the staining differs strongly between nuclei (Figure 3E). Altogether, these experiments on salivary glands indicate that crm is specifically required for the direct and stable repression of ci by PH.

Further evidence supporting a role for crm in the silencing of ci comes from examining white marked transposons inserted near the ci locus. Previously, a Polycomb response element (PRE) has been mapped on a 1Kb fragment, 4 kb upstream of ci [26] (see Figure 3A). Two Drosophila deletion lines, Df(4)ED6364 and Df(4)ED6366, differing by a 10 kb region covering the ci PRE, contain a copy of the white gene, in an identical transgene, just upstream of ci [27] (Figure 3A). The silencing effect of the region containing the PRE can be seen in these two lines, which have markedly different eye colors. Df(4)ED6366, which retains the PRE is variegated and much lighter than Df(4)ED6364, in which the PRE is absent (Figure 3F). When the deletion retaining the PRE (Df(4)ED6366), is introduced in ph heterozygote females or crm32 mutant males, the eye color becomes uniform and much darker, showing that both ph and crm are required for the repression of the white transgene (Figure 3G, 3H). As in the line Df(4)ED6366, the white gene is inserted around 10kb upstream of ci (approximately 400 bp downstream of the dTcf promoter), we believe that more than just ci is sensitive to the PRE. In agreement with this hypothesis, previous mapping of Polycomb (Pc) binding sites revealed that the whole ci-dTcf region corresponds to a Pc enriched domain, centered on ci, but reaching the promoter of dTcf [28] (Figure 3A).

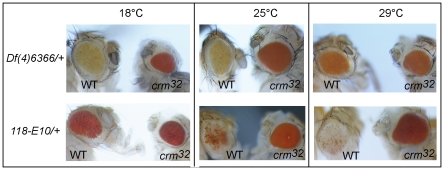

Temperature modulates chromatin regulation in the ci-dTcf region

Interestingly, ci lies close to the fourth chromosome pericentromeric heterochromatin. This heterochromatic environment is required for ci regulation as translocations separating ci from the pericentromeric heterochromatin of the fourth chromosome do not fully complement the ci1 mutant allele [29]–[31]. Furthermore, previous data suggested that silencing by constitutive heterochromatin is stronger at low temperatures, whereas PcG silencing is stronger at higher temperatures [18]. We therefore investigated whether this antagonistic effect of temperature also applies to the genomic region around ci.

We analyzed the effect of temperature on chromatin regulation in the ci-dTcf region using the line Df(4)ED6366. To compare it to the effect of temperature on neighboring constitutive heterochromatin, we used the line 118E10, carrying a transgene inserted in fourth chromosome pericentromeric heterochromatin [32]. We observed that high temperature reduces silencing in the ci-dTcf region (Figure 4). In contrast, we observed a strong reduction of PEV at low temperature with the line 118E10. The down regulation of the reporter gene near pericentromeric heterochromatin therefore shows temperature sensitivity opposite to that of the neighboring ci-dTcf region in the eye (Figure 4). Furthermore, mutating crm de-represses the monitored reporter genes at all temperatures tested, in both lines. Silencing of the ci-dTcf region is weaker in crm mutants at all temperatures, but this effect is particularly pronounced at low and intermediate temperature (Figure 4). Thus, crm is essential for the stronger down regulation observed at low temperature. Furthermore, LOF mutation in crm, has a strong effect on the 118E10 transgene in particular at intermediate and high temperature (Figure 4). This confirms a role for crm in the formation of constitutive heterochromatin, previously shown with X chromosome pericentromeric heterochromatin [17] and shows that crm is required for the stronger silencing by pericentromeric heterochromatin observed at high temperature.

Figure 4. The regulation of the ci-dTcf region is temperature sensitive.

Comparison of the effect of crm LOF and temperature on the expression of white in the transgenes from the lines Def(4)6366 and 118E-10.

ci and dTcf are the effectors of the Hedgehog (Hh) and Wingless (Wg) signaling pathways. These two major signaling pathways (and the dpp signaling pathway that is regulated by them) are involved in the development of many morphological traits, including several temperature sensitive traits under the control of crm, such as abdominal dorsal fusion and sex comb development [33]–[35]. In addition, Hedgehog and Wingless regulate together dpp and optomotor-blind/bifid (omb/bi), both involved in the control of abdominal pigmentation, a very plastic trait [23], [36]–[38]. As the regulation of the ci-dTcf region is temperature sensitive, it likely contributes to the thermal plasticity of these traits.

crm natural variants shift the reaction norms of plastic traits

We designed sensitive phenotypic tests based on the results above to analyze functional differences between natural alleles. As we expected these differences to be much weaker than those observed with typical laboratory mutants and to be obscured by variation at other loci, we performed the tests in isogenic backgrounds to remove the effect of variation at other loci (see Methods). Four crm alleles corresponding to the pairwise combinations of the two amino acid polymorphisms A639G and T842M that are presumably affected by adaptation in cosmopolitan D. melanogaster were tested. We scored abdominal pigmentation in females, and distal sex combs or posterior sex combs in males (Figure S5). Because D. melanogaster males do not have distal or posterior sex combs, we analyzed the modification by the crm variants of the ectopic distal or posterior sex comb phenotypes induced by mutations in genes interacting with crm (see Methods). In addition, we tested the effect of crm natural variants on the ci-dTcf region. For this, we analyzed how they modify the wing vein phenotype caused by the dominant allele ciD, which induces an ectopic expression of ci in the posterior compartment [31]. This phenotype was shown previously to be very sensitive to both natural genetic variation and temperature [39]. We observed indeed a strong interaction with temperature as the ciD vein gap phenotype was not visible in flies grown at 18°C. We analyzed it only for flies grown at 25°C (Figure S5). These dominant sex comb and wing vein phenotypes are therefore not used as wild type traits, but as read out to compare the effects of the crm natural variants on crm sensitive processes.

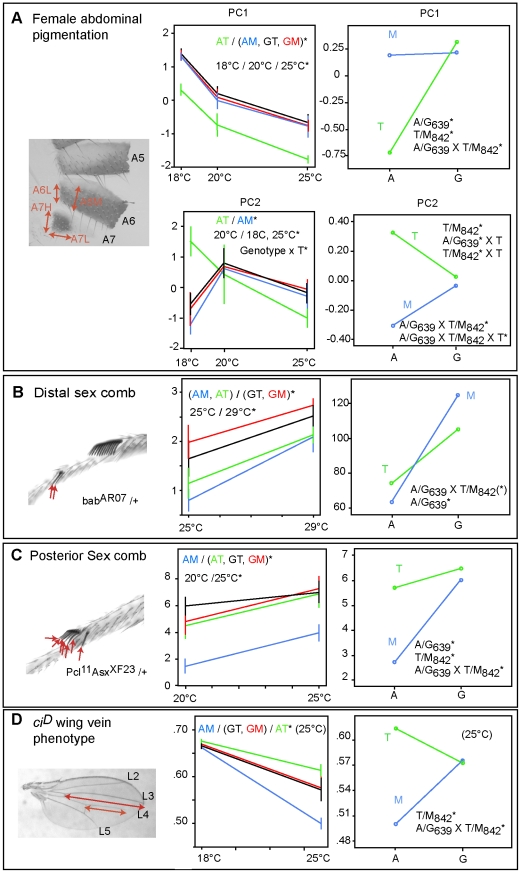

The four crm variants have different reaction norms for all traits: abdominal pigmentation (Two-way ANOVA PC1 p<0.001 and PC2 p<0.005), distal sex combs (Scheirer-Ray-Hare test p<0.05), posterior sex combs (Two-way ANOVA p<0.01), and ciD phenotype (One-way ANOVA p<0.001). However, depending on the phenotypic trait, the crm variants behave differently (Figure 5). The AT combination, which represents an African variant is different from the two non-African variants (GT and GM), for female abdominal pigmentation, distal sex combs and the ciD phenotype. A significant genotype X temperature interaction is observed for female abdominal pigmentation with this allele (principal component 2). The artificial AM form is clearly different from all three other variants for the posterior sex comb and the ciD phenotypes. It groups together with the AT variant for distal sex combs.

Figure 5. Phenotypic analysis of CRM natural variants.

A, B, C, D left: Plots of the mean phenotypes (with 95% confidence interval) scored for each genotype in different temperature conditions. For female abdominal pigmentation, we used the first and second principal components extracted from the four pigmentation scores. The significant differences of genotypes and temperatures according to post hoc tests are indicated. Because the vein gap phenotype was visible only at 25°C, we analyzed it only at this temperature (D). Right: Interaction plots with estimated marginal means for the same phenotypic traits showing interaction between the two polymorphic amino acids A639G and T842M. Significant main effects and interactions are indicated. The A639G×T842M interaction for the distal sex comb is significant with a two way anova on ranked data, but not according to the non parametric ANOVA (Scheirer-Han extension of the Kruskall-Wallis test).

To partition the effect of each site on the phenotype, we used three-way ANOVA. In addition to temperature (p<0.001 for all traits), we found significant main effects for each of the polymorphic sites with posterior sex combs and pigmentation. For distal sex combs, the A639G polymorphism, (but not the T842M polymorphism) has a significant main effect (Scheirer-Ray-Hare test p<0.01). In addition, the two polymorphic sites show significant interactions for all traits. In other words, our data show strong intra-molecular epistasis (posterior sex comb p<0.001; pigmentation p<0.001; ciD phenotype <0.001) (Figure 5). For the distal sex comb, the interaction A639G×T842M is significant for the ANOVA on ranks (p = 0.01), but not with the very conservative Scheirer-Ray-Hare test (p = 0.37).

Discussion

In a genome wide screen for adaptation during the out of African expansion of Drosophila melanogaster, crm was identified as a candidate gene [16]. Consistent with a role for crm in adaptation to temperature, we show here, using mutants, that crm is limiting for different developmental regulatory processes at distinct temperatures. We identified the ci-dTcf region as particularly sensitive to crm. crm affects ci regulation through both constitutive heterochromatin and Polycomb silencing. Our results based on white expression in the eye suggest that pericentromeric heterochromatin is negatively correlated to Polycomb silencing in the ci-dTcf region and that temperature affects inversely Polycomb silencing and pericentromeric heterochromatin. This temperature sensitivity of the ci-dTcf regulation contributes to phenotypic plasticity. By maintaining Polycomb silencing and constitutive heterochromatin, crm appears to contribute to environmental canalization of plastic traits.

Our analysis shows that crm natural variants shift the reaction norms of plastic traits. We observe two effects: a change in slope indicating a modification of the environmental canalization of these traits, or a change in mean, interpretable as genetic compensation (see below). The ancestral combination A639T842 present in Africa reduces the ectopic distal sex comb and the ciD phenotypes. Compared to the European combinations GT and GM, it reduces the effect of high temperature on these traits, allowing different genotypes to maintain similar phenotypes in different environments, a process called genetic compensation [6]. The ancestral African combination AT also decreases female abdominal pigmentation and interacts with temperature for this trait (principal component 2). Abdominal pigmentation shows a complex pattern of geographical variation with both pale and dark phenotypes observed in Sub-Saharan and European regions [40], [41]. In general, flies living in colder regions (high altitude in Africa, Europe versus Indian) are more pigmented [42], [43]. It is thought to be adaptive because darker flies warm up more quickly [15]. The reduced pigmentation of the ancestral African combination A639T842 fits therefore this thermal budget hypothesis.

An effect of the G842M mutation is observed in our tests only in combination with A639. The AM form is observed neither in Africa nor in Europe, because the T842M mutation likely occurred on a G639T842 haplotype. This combination could theoretically be produced by recombination between African AT and European GM forms. Interestingly, admixture between European and African Drosophila melanogaster populations is known to have happened in America [44], [45]. In a limited sequencing survey, such a combination (A639M842) was identified in a population from the Caribbean island Gossier, indicating that it actually exists in the wild (Harr and Schlötterer, unpublished data). As our phenotypic tests show that this recombinant form differs functionally strongly from the others, future studies on Caribbean flies could provide interesting insights on the modulation of the crm network.

The strong epistasis we observe between the two amino acid positions suggest that the elevated divergence observed in these regions between closely related Drosophila species might be caused by a permanent adjustment of one region to the other in particular environmental conditions. Although the molecular interactions modulated by these amino acid polymorphisms are unknown, we note that these regions contain several potential sites of phosphorylation. Our results suggest that amino acid replacements in pleiotropic factors play a significant role in evolution. In contrast, recent studies have stressed the role of regulatory sequences in evolution as their modification has less pleiotropic consequences than amino acid changes [46]. However comparison of closely related species such as D. melanogaster and D. simulans reveals that many amino acid replacements seem to be under positive but weak selection [47]. Our results suggest that many of these changes might correspond to compensatory mutations adjusting to variation in other genomic regions and environmental conditions to stabilize gene regulatory networks.

Other studies analyzing natural variation have suggested also a role of several chromatin regulators in adaptation to different temperature regimes [48]. In addition, African alleles of PH, the Polycomb group factor that requires crm to bind to the ci region, also shows the footprint of positive selection [49]. Furthermore, the bab locus, which interacts genetically with crm, harbors natural variation that strongly modulates abdominal pigmentation [50]. Thus, a whole network of chromatin regulators is apparently involved in local temperature adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. Interestingly, distal sex comb and abdominal pigmentation, which are modulated by crm polymorphisms and are also regulated by bab and ph in Drosophila melanogaster, can differ markedly between Drosophila species [51]–[53]. It suggests that local adaptation might facilitate the evolution of these traits, although it probably primarily optimizes other more crucial correlated temperature sensitive traits. For example, ovary development or male fertility are also temperature sensitive and show geographical variation [15], [54]. We do not mean that selection does not play any role in the evolution of sex combs or pigmentation. Indeed, the sex comb is under strong selection as its genetic ablation reduces mating performance [55]. Similarly, clinal and altitudinal variation suggest that abdominal pigmentation is under selection [42], [43]. However, selection can act only if genetic variation has phenotypic consequences. We suggest that by maintaining functional genetic variation in temperature sensitive gene networks, environment heterogeneity contribute to the high evolvability of particular correlated traits.

Material and Methods

CRM natural variation and divergence

We used the data set previously published [16] and added the crm haplotype from the sequenced strain of Drosophila melanogaster [56]. As outgroup we used a crm haplotype from Drosophila sechellia [16] and a consensus between the sequenced traces from different Drosophila simulans haplotypes (Genome sequencing center, Washington School of Medicine).

We used TREE-PUZZLE 5.2 [57] with the Tamura-Nei (1993) model of sequence evolution to build maximum likelihood phylogenies using the nucleotide sequences of the region A, B and C. Region A (1000 bp) and B (576bp) are two parts of exon 4. Region C (374bp) corresponds to the exon 5.

Ka/Ks ratio was analyzed using all the D. melanogaster and the Drosophila simulans CRM coding sequences with 50 sites windows step size of 10, excluding sites with gaps, using DNASP5 [58].

CRM homolgues were identified by BLAST in other Drosophila (D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, D. wilistoni, D. mojavensis, D. virilis and D. grimshawi), the mosquito Aedes aegypti, the beetle Tribolium castaneum, the aphid A. pisum, the wasp Nasonia vitripennis, the chelicerate I. scapularis, several vertebrates including Homo sapiens and the zebrafish B. rerio, two basal metazoans, the cnidarian N. vectensis and the placozoan T. adherens, several plants (including A. thaliana and O. sativa) and an alga M. pusilla.

Sequences were aligned using clustal w [59]. Alignments were improved manually. In order to associate the prediction of disordered domains in Drosophila melanogaster CRM and the level of conservation with its homologues (Figure 1C), positions with a gap in the D. melanogaster CRM were removed from the alignment. Similarity index was calculated with the JProfieGrid Software with a window size of 5 and a threshold of 0.7 [60]. Disorder tendency was calculated for the D. melanogaster CRM sequence using the IUpred server [19].

Origin and maintenance of the fly stocks

The crm32 null allele was generated by imperfect excision of the P-element inserted in the line P{EPgy2}crmEY05302. The promoter and the first 286 codons are deleted. All other fly stocks are described in flybase (http://flybase.org). Flies were grown on standard agar-corn medium. We used standard balancer chromosomes.

Generation of CRM deletion mutants

WT or mutant crm coding sequences with deletion of particular conserved domains were inserted in frame 3′ to the coding sequence of the fluorescent protein Venus [61] in the vector PUAST-attB [62]. The amino acid deleted in the mutant forms were: 68–271 (replaced by a proline, CRM-Del-I), 351–476 (CRM-Del-II), 487–621 (CRM-Del-III), 620–747 (replaced by an alanine, CRM-Del-IV), 736–821 (CRM-Del-V), 848–950 (CRM-Del-VI) and 951–982 (CRM-Del-VII). The crm cDNA used to construct these forms was the clone LD29481 from the BDGP Gold collection. The obtained plasmids were integrated in the plattform 22A on the second chromosome using the PhiC31 transgenesis method [62]. They are thus under the same position effects and can be compared to one another.

Generation of isogenic stocks with different crm natural variants

We generated in vitro the four pairwise combinations of the amino acid variants A639G (GCC/GGC) and T842M (ACG/ATG). The mutagenesis was performed on a 4912 pb genomic fragment containing the crm allele from the OregonR stock (G639T842 allele). The genomic fragments (including crm regulatory sequences) were cloned in a modified PUAST-attB vector where a PstI-EcoRI fragment containing the HSP70 promoter and the UAS sequences was replaced by a primer containing the restriction sites PstI, NdeI, StuI and EcoRI. We used a natural NotI site present in the middle of the crm genomic fragment to amplify and clone independantly the 5′ half (2621 pb including a BglII restriction site added to the direct primer) and 3′ half (2312 pb including an XbaI site added to the reverse primer) of OregonR crm in the pGEMT easy cloning vector. Sequences were checked for error. The 5′ half was cloned first using the restriction sites BglII and NotI in the modified PUAST-attB vector. The allele G639M842 was amplified from a Drosophila melanogaster dutch line, Tex12, differing only by the substitution responsible for the T842M replacement from OrR. The reverse mutation G639A was induced using a primer by PCR in a strategy similar to the QuickChangeR Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and checked by sequencing. The four different 3′ crm halves were cloned using the restriction sites NotI and XbaI 3′ to the 5′ half of crm. The obtained plasmids were integrated in the plattform 22A on the second chromosome using the PhiC31 transgenesis method [62]. We introduced them in an isogenic y, crm32 mutant background using balancer chromosomes and a fourth chromosome labeled by a Pw+ transgene. The third chromosome used to construct these stocks was extracted from the OregonR stock.

Staining protocols

LacZ staining on drosophila tissues [63] and immunostaining on squashed polytene chromosomes were done as previously described [23]. Immuno-staining on whole mount salivary glands and imaginal discs were done according to standard protocols. We used monoclonal mouse anti Beta-galactosidase (Promega, Z378), and rabbit anti-PH [26]. Observation and image capture of immuno-fluorescent staining were made on an Axioplan microscope (Zeiss) with an Optronix camera and Magnafire software.

Phenotypic tests of crm natural alleles

We scored abdominal pigmentation in females homozygotes for each of the four alleles in a crm32 isogenic mutant background grown at 18, 20 or 25°C. They were identical and thus not informative at 29°C. We scored four pigmentation traits on each side: width of the transversal melanin stripe in the lateral region of the sixth tergite (A6L) and in the middle of the sixth hemitergite (A6M), width of the melanic pigmentation along the anteroposterior axis in the lateral region of the seventh tergite (A7H) and length of melanic pigmentation along the dorso-ventral axis in the seventh tergite (A7L). For the restriction of the sex comb, because wild type flies do not show ectopic sex comb, we analyzed how crm natural alleles modify the ectopic sex comb induced by mutations in particular genes interacting with crm. We used heterozygosity for a loss of function mutation at the bric-à-brac locus (babAR07) to induce a distal sex comb phenotype as it was shown previously to interact genetically particularly strongly with crm [23]. In a distinct phenotypic test, we used a second chromosome carrying mutant alleles of Polycomblike (Pcl11) and Additionnal sex comb (AsxXF23) to induce a strong ectopic sex comb phenotype on the second and third leg. We scored the number of sex comb teeth on the third leg.

For the two sex comb traits, we crossed, at particular temperatures, females homozygote for particular crm alleles (on the second chromosome) in a crm32 mutant background with males from freshly isogenized stocks carrying the tester mutation over a balancer chromosome (babAR07/TM6b or AsxXF23, Pcl11/CyO). We scored sex comb phenotypes in the male progeny (carrying the crm32 allele on the X chromosome, heterozygote for the rescue allele inserted on the second chromosome and heterozygote for the tester mutations). Bristles partially transformed into sex comb teeth (identified by the presence of a large socket) were scored as sex comb teeth in the babAR07 test. Ectopic sex comb teeth were always unambiguously identifiable in the Pcl11AsxXF23 test.

For the wing vein phenotype caused by the ciD allele, we crossed, at 18 and 25°C, females homozygote for particular crm alleles (on the second chromosome) in a crm32 mutant background with males from a freshly isogenized ciD/eyD. We scored the wing vein phenotype in the male progeny (carrying the crm32 allele on the X chromosome, heterozygote for the rescue allele inserted on the second chromosome and heterozygote for ciD). We did not detect any vein gaps in flies grown at 18°C, which shows that the ciD phenotype is extremely temperature sensitive as previously described [39]. We therefore used only the flies grown at 25°C for statistical analyzes. We calculated the ratio between the length of the intact portion of the fourth vein distally to the posterior crossvein and the length of the third vein portion distal to the anterior crossvein (Figure 5D). Vein lengths were measured using the “Measure” function and the “line” tool of the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 17. Phenotypes were scored on both sides and averaged between left and right side for each individual. Means and standard deviation are given in Figure S5. Plotting of the data showed that the four pigmentation traits were strongly correlated (Figure S6) so we extracted principal components. The first component captured more than 82% of the total variance and had an eigen value of 3.311. The second component captured 9.9% of the total variance (eigen value 0.396). We therefore used only these two components. We used ANOVA when the residuals did not deviate significantly from normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, p>0.05). The phenotypic data were analyzed using two way ANOVA (genotype, temperature) and three way ANOVA (Temperature, A639G, T842M) except the distal sex comb data which did not respect the assumptions of parametric test. For this data set we used non parametric ANOVA on ranked data (Scheirer-Ray-Hare extension of the Kruskal-Wallis test) and calculated p values using SS/MS total and degrees of freedom [64]. One way ANOVA (genotype) and two-way ANOVA (A639G, T842M) were used to analyzed ciD data. In order to evaluate the effect size we calculated classical eta squared from the type III Sum of Squares provided in the ANOVA output by SPSS for abdominal pigmentation and posterior sex combs as SSfactor/SScorrected total. Tukey post hoc tests were performed to identify the differences between genotypes for pigmentation and posterior sex combs. For the distal sex comb phenotype we use Tamhane post hoc test, which does not assume equality of variance. Statistical analysis can be found in Figure S7.

Supporting Information

Molecular phylogenies using maximum likelihood based on the nucleotide sequences of region A, B, and C (see Materials and Methods). The data set contains 7 African sequences, 27 European sequences from two populations, and the sequence from the strain sequenced for the genome project. Color code identifies haplotypes sharing the same combination of the amino acids discussed in the text. In A, B and C, the ancestral combination is colored in yellow. Red dots identify African alleles.

(0.32 MB TIF)

Schematic representation of the nucleotide haplotypes in regions A, B, and C. Each color represents a single haplotype in region A, B, and C. In region A, several haplotypes correspond to a unique amino acid combination. It is visible that several events of recombination have occurred between the different regions. The primitive combinations are represented at the top of the figure.

(1.64 MB TIF)

Morphological defects observed in crm mutants can be enhanced selectively by mutations in particular chromatin regulators. Mutation in Su(var)3.9 reduces the number of sex comb teeth in ectopic and normal sex combs and enhances abdominal dorsal fusion defects. Mutation in Polycomb-like dramatically enhances ectopic posterior sex comb phenoytpes.

(5.00 MB TIF)

Phenotypic analysis of CRM mutant forms. The deletion of a conserved domain often turns the protein into a toxic product more deleterious than a null mutant (dominant negative), which can be very useful to identify limiting process in which a particular factor is involved. We use this approach to generate 7 crm mutant forms, by deleting domains I to VII (A). We tested their effect on wing development using the bi-gal4 driver (E). A single wing is illustrated, but more than ten wings were observed for each genotype and show consistent phenotypes. Deletion II, VI and, to a lesser extant V, induce both distal and posterior sex comb (B). Deletion V leads to dorsal fusion defects with da-GaL4 (B) and with pnr-GAL4 (expressed in the dorsal region) to increased melanin production both on the thorax in both sexes and in the 4th abdominal segment in males (D).

(4.02 MB TIF)

Mean, standard deviation, and sample size for the phenotypes scored to analyze the effect of CRM natural variants.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Plots of the raw data for the four pigmentation traits scored on female abdomen.

(0.60 MB TIF)

Statistical analysis of the phenotypic traits used to characterize functionally crm natural variants.

(0.19 MB DOC)

Description of CRM coding haplotypes.

(0.02 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock center (Bloomington, USA), Marion Delattre (Geneva, Switzerland), and Frédérique Peronnet (Paris, France) for fly stock and/or reagents. We thank Henrik Gyurkovics (Szeged, Hungary), Rob Maeda (Geneva, Switzerland), Alistair McGregor (Vienna, Austria), Martin Müller (Basel, Switzerland), Frédérique Peronnet (Paris, France), and all members of the Karch, Pauli, Spierer, and Schlötterer groups for stimulating discussions. FlyBase provided important information used in this work.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

J-MG was a recipient of the Lise Meitner Fellowship (M804-B14). CS was the recipient of an Austrian Science Fund grant (FWF, P19467-B11). The Donation Claraz and grants from the state of Geneva and from the Swiss National Fund supported the work. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Crickmore MA, Ranade V, Mann RS. Regulation of Ubx expression by epigenetic enhancer silencing in response to Ubx levels and genetic variation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meireles-Filho AC, Stark A. Comparative genomics of gene regulation-conservation and divergence of cis-regulatory information. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankel N, Davis GK, Vargas D, Wang S, Payre F, et al. Phenotypic robustness conferred by apparently redundant transcriptional enhancers. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry MW, Boettiger AN, Bothma JP, Levine M. Shadow enhancers foster robustness of Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waddington CH. Canalization of development and genetic assimilation of acquired characters. Nature. 1959;183:1654–1655. doi: 10.1038/1831654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grether GF. Environmental change, phenotypic plasticity, and genetic compensation. Am Nat. 2005;166:E115–123. doi: 10.1086/432023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Via S, Gomulkievicz R, de Jong G, Scheiner SM, Schlichting CD, et al. Adaptive phenotypic plasticity: consensus and controversy. TREE. 1995;10:212–217. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki Y, Nijhout HF. Evolution of a polyphenism by genetic accommodation. Science. 2006;311:650–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1118888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson G, Hogness DS. Effect of polymorphism in the Drosophila regulatory gene Ultrabithorax on homeotic stability. Science. 1996;271:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moczek AP. Developmental capacitance, genetic accommodation, and adaptive evolution. Evol Dev. 2007;9:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price TD, Qvarnström A, Irwin DE. The role of phenotypic plasticity in driving genetic evolution. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2003;270:1433–1440. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(Suppl 1):6543–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501844102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trotta V, Calboli FCF, Ziosi M, Guerra D, Pezzoli MC, et al. Thermal plasticity in Drosophila melanogaster: a comparison of geographical population. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouletreau-Merle J, Fouillet P, Varaldi J. Divergent strategies in low temperature environment for the sibling species Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: overwintering in extension borders area of France and comparison with African populations,. Evolutionary Ecology. 2003;17:523–548. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibert P, Capy P, Imasheva A, Moreteau B, Morin JP, et al. Comparative analysis of morphological traits among Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: genetic variability, clines and phenotypic plasticity. Genetica. 2004;120:165–179. doi: 10.1023/b:gene.0000017639.62427.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harr B, Kauer M, Schlotterer C. Hitchhiking mapping: a population-based fine-mapping strategy for adaptive mutations in Drosophilamelanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12949–12954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202336899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto Y, Girard F, Bello B, Affolter M, Gehring WJ. The cramped gene of Drosophila is a member of the Polycomb-group, and interacts with mus209, the gene encoding Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen. Development. 1997;124:3385–3394. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fauvarque MO, Dura JM. polyhomeotic regulatory sequences induce developmental regulator-dependent variegation and targeted P-element insertions in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1508–1520. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hegyi H, Schad E, Tompa P. Structural disorder promotes assembly of protein complexes. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittag T, Kay LE, Forman-Kay JD. Protein dynamics and conformational disorder in molecular recognition. J Mol Recognit. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jmr.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pattatucci AM, Kaufman TC. The homeotic gene Sex combs reduced of Drosophila melanogaster is differentially regulated in the embryonic and imaginal stages of development. Genetics. 1991;129:443–461. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibert JM, Peronnet F, Schlotterer C. Phenotypic Plasticity in Drosophila Pigmentation Caused by Temperature Sensitivity of a Chromatin Regulator Network. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e30. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schotta G, Ebert A, Krauss V, Fischer A, Hoffmann J, et al. Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3-9 in histone H3-K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. Embo J. 2002;21:1121–1131. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehsan H, Reichheld JP, Durfee T, Roe JL. TOUSLED kinase activity oscillates during the cell cycle and interacts with chromatin regulators. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1488–1499. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.038117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chanas G, Lavrov S, Iral F, Cavalli G, Maschat F. Engrailed and polyhomeotic maintain posterior cell identity through cubitus-interruptus regulation. Dev Biol. 2004;272:522–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryder E, Blows F, Ashburner M, Bautista-Llacer R, Coulson D, et al. The DrosDel collection: a set of P-element insertions for generating custom chromosomal aberrations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004;167:797–813. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Wit E, Greil F, van Steensel B. High-resolution mapping reveals links of HP1 with active and inactive chromatin components. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubinin NP, Sidorov BN. Relation between the effect of a gene and its position in the system. Am Naturalist. 1934;18:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demakova OV, Belyaeva ES, Zhimulev IF. The somatic pairing of homologues of chromosome 4 causes the suppression of the Dubinin effect in Drosophila melanogaster. Russian Journal of Genetics. 1998;34:511–516. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locke J, Tartof KD. Molecular analysis of cubitus interruptus (ci) mutations suggests an explanation for the unusual ci position effects. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:234–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00280321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallrath LL, Elgin SC. Position effect variegation in Drosophila is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1263–1277. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minakuchi C, Zhou X, Riddiford LM. Kruppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) mediates juvenile hormone action during metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Dev. 2008;125:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker DS, Jemison J, Cadigan KM. Pygopus, a nuclear PHD-finger protein required for Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:2565–2576. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svendsen PC, Marshall SD, Kyba M, Brook WJ. The combgap locus encodes a zinc-finger protein that regulates cubitus interruptus during limb development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2000;127:4083–4093. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Towards a model of the organisation of planar polarity and pattern in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 2002;129:2749–2760. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopp A, Duncan I. Control of cell fate and polarity in the adult abdominal segments of Drosophila by optomotor-blind. Development. 1997;124:3715–3726. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopp A, Blackman RK, Duncan I. Wingless, decapentaplegic and EGF receptor signaling pathways interact to specify dorso-ventral pattern in the adult abdomen of Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:3495–3507. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scharloo W. The influence of selection and temperature on a mutant character (ciD) in Drosophila melanogaster. Arch Neerl Zool. 1962;14:433–511. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rebeiz M, Pool JE, Kassner VA, Aquadro CF, Carroll SB. Stepwise modification of a modular enhancer underlies adaptation in a Drosophila population. Science. 2009;326:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1178357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibert P, Moreteau B, David JR. Phenotypic plasticity of body pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster: genetic repeatability of quantitative parameters in two successive generations. Heredity. 2004;92:499–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pool JE, Aquadro CF. The genetic basis of adaptive pigmentation variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:2844–2851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibert P, Moreteau B, Moreteau J-C, Parkash R, David JR. Light body pigmentation in Indian Drosophila melanogaster: a likely adaptation to a hot and arid climate. Journal of Genetics. 1998;77:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caracristi G, Schlotterer C. Genetic differentiation between American and European Drosophila melanogaster populations could be attributed to admixture of African alleles. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:792–799. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yukilevich R, True JR. African morphology, behavior and phermones underlie incipient sexual isolation between us and Caribbean Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution. 2008;62:2807–2828. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prud'homme B, Gompel N, Carroll SB. Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(Suppl 1):8605–8612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawyer SA, Parsch J, Zhang Z, Hartl DL. Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6504–6510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701572104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levine MT, Begun DJ. Evidence of Spatially Varying Selection Acting on Four Chromatin-Remodeling Loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;179:475–485. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beisswanger S, Stephan W. Evidence that strong positive selection drives neofunctionalization in the tandemly duplicated polyhomeotic genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5447–5452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710892105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopp A, Graze RM, Xu S, Carroll SB, Nuzhdin SV. Quantitative trait loci responsible for variation in sexually dimorphic traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;163:771–787. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kopp A, Barmina O. Evolutionary history of the Drosophila bipectinata species complex. Genet Res. 2005;85:23–46. doi: 10.1017/s0016672305007317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopp A, True JR. Evolution of male sexual characters in the oriental Drosophila melanogaster species group. Evol Dev. 2002;4:278–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2002.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wittkopp PJ, Carroll SB, Kopp A. Evolution in black and white: genetic control of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Trends Genet. 2003;19:495–504. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00194-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rohmer C, David JR, Moreteau B, Joly D. Heat induced male sterility in Drosophila melanogaster: adaptive genetic variations among geographic populations and role of the Y chromosome. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:2735–2743. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng CS, Kopp A. Sex Combs are Important for Male Mating Success in Drosophila melanogaster. Behav Genet. 2008;38:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A. TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:502–504. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roca AI, Almada AE, Abajian AC. ProfileGrids as a new visual representation of large multiple sequence alignments: a case study of the RecA protein family. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:554. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific {varphi}C31 integrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. hedgehog and engrailed: pattern formation and polarity in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 1999;126:2431–2439. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dytham C. Choosing and using statistics: a biologist's guide, 2nd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boyer LA, Latek RR, Peterson CL. The SANT domain: a unique histone-tail-binding module? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:158–163. doi: 10.1038/nrm1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bushey D, Locke J. Mutations in Su(var)205 and Su(var)3-7 suppress P-element-dependent silencing in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004;168:1395–1411. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun FL, Haynes K, Simpson CL, Lee SD, Collins L, et al. cis-Acting determinants of heterochromatin formation on Drosophila melanogaster chromosome four. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8210–8220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8210-8220.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun FL, Cuaycong MH, Craig CA, Wallrath LL, Locke J, et al. The fourth chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: interspersed euchromatic and heterochromatic domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5340–5345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090530797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Molecular phylogenies using maximum likelihood based on the nucleotide sequences of region A, B, and C (see Materials and Methods). The data set contains 7 African sequences, 27 European sequences from two populations, and the sequence from the strain sequenced for the genome project. Color code identifies haplotypes sharing the same combination of the amino acids discussed in the text. In A, B and C, the ancestral combination is colored in yellow. Red dots identify African alleles.

(0.32 MB TIF)

Schematic representation of the nucleotide haplotypes in regions A, B, and C. Each color represents a single haplotype in region A, B, and C. In region A, several haplotypes correspond to a unique amino acid combination. It is visible that several events of recombination have occurred between the different regions. The primitive combinations are represented at the top of the figure.

(1.64 MB TIF)

Morphological defects observed in crm mutants can be enhanced selectively by mutations in particular chromatin regulators. Mutation in Su(var)3.9 reduces the number of sex comb teeth in ectopic and normal sex combs and enhances abdominal dorsal fusion defects. Mutation in Polycomb-like dramatically enhances ectopic posterior sex comb phenoytpes.

(5.00 MB TIF)

Phenotypic analysis of CRM mutant forms. The deletion of a conserved domain often turns the protein into a toxic product more deleterious than a null mutant (dominant negative), which can be very useful to identify limiting process in which a particular factor is involved. We use this approach to generate 7 crm mutant forms, by deleting domains I to VII (A). We tested their effect on wing development using the bi-gal4 driver (E). A single wing is illustrated, but more than ten wings were observed for each genotype and show consistent phenotypes. Deletion II, VI and, to a lesser extant V, induce both distal and posterior sex comb (B). Deletion V leads to dorsal fusion defects with da-GaL4 (B) and with pnr-GAL4 (expressed in the dorsal region) to increased melanin production both on the thorax in both sexes and in the 4th abdominal segment in males (D).

(4.02 MB TIF)

Mean, standard deviation, and sample size for the phenotypes scored to analyze the effect of CRM natural variants.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Plots of the raw data for the four pigmentation traits scored on female abdomen.

(0.60 MB TIF)

Statistical analysis of the phenotypic traits used to characterize functionally crm natural variants.

(0.19 MB DOC)

Description of CRM coding haplotypes.

(0.02 MB DOC)