Abstract

Background -

The availability of multiple whole genome sequences has facilitated in silico identification of fixed and polymorphic transposable elements (TE). Whereas polymorphic loci serve as makers for phylogenetic and forensic analysis, fixed species-specific transposon insertions, when compared to orthologous loci in other closely related species, may give insights into their evolutionary significance. Besides, TE insertions are not isolated events and are frequently associated with subtle sequence changes concurrent with insertion or post insertion. These include duplication of target site, 3' and 5' flank transduction, deletion of the target locus, 5' truncation or partial deletion and inversion of the transposon, and post insertion changes like inter or intra element recombination, disruption etc. Although such changes have been studied independently, no automated platform to identify differential transposon insertions and the associated array of sequence changes in genomes of the same or closely related species is available till date. To this end, we have designed RISCI - 'Repeat Induced Sequence Changes Identifier' - a comprehensive, comparative genomics-based, in silico subtractive hybridization pipeline to identify differential transposon insertions and associated sequence changes using specific alignment signatures, which may then be examined for their downstream effects.

Results -

We showcase the utility of RISCI by comparing full length and truncated L1HS and AluYa5 retrotransposons in the reference human genome with the chimpanzee genome and the alternate human assemblies (Celera and HuRef). Comparison of the reference human genome with alternate human assemblies using RISCI predicts 14 novel polymorphisms in full length L1HS, 24 in truncated L1HS and 140 novel polymorphisms in AluYa5 insertions, besides several insertion and post insertion changes. We present comparison with two previous studies to show that RISCI predictions are broadly in agreement with earlier reports. We also demonstrate its versatility by comparing various strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for IS 6100 insertion polymorphism.

Conclusions -

RISCI combines comparative genomics with subtractive hybridization, inferring changes only when exclusive to one of the two genomes being compared. The pipeline is generic and may be applied to most transposons and to any two or more genomes sharing high sequence similarity. Such comparisons, when performed on a larger scale, may pull out a few critical events, which may have seeded the divergence between the two species under comparison.

Background

Mobile or transposable elements (TEs) are DNA sequences that have the ability to hop (transpose) in the genome, within their cell of origin. TEs constitute a highly diverse class of repeat elements [1,2] and have been reported in all genomes sequenced till date except Plasmodium falciparum [[3], reviewed in [4]]. Based on the mechanism of transposition [reviewed in [5]], TEs are broadly divided into two classes - Class I or Retrotransposons and Class II or DNA transposons. Retrotransposons transpose via an RNA intermediate which is reverse transcribed and integrated into the genome, thereby duplicating the element (copy paste mechanism). DNA transposons, on the other hand, excise from their source locus to reinsert at a new one without the involvement of an RNA intermediate (cut paste mechanism) [1].

TEs represent miniature genomes with a versatile repertoire of cis regulatory elements and/or trans acting factors. Long relegated as selfish DNA [6,7], they are turning out to be a treasure trove of genomic novelties as their impact on host genome evolution is beginning to be understood [8-13]. Besides serving as an inexhaustible source of novel genes and exons [13-20], gene functions [21-23], and regulatory motifs and signals [24-27], the insertion of a transposon at a locus may change its properties drastically with local and/or long range or global consequences [10,28-31]. These changes are more palpable when a transposon insertion results in gene disruption and is manifested as a disease condition [32-34]. Such insertions may be subject to negative selection and lost in due course [35].

Most transposon insertions that persist are, therefore, either silent or result in subtle and/or adaptive changes. The cumulative impact of these subtle changes may account for the observed phenotypic, physiological and behavioral differences between closely related genomes that share a high degree of sequence similarity [36]. Notable examples include human-specific inactivation of the CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase gene via Alu- mediated replacement resulting in widespread biochemical difference between human and non human primates [37] and the loss of exon 34 of tropleolastin gene in human via an Alu recombination-mediated deletion [38].

The challenge, then, is to selectively identify these differential insertions and the consequent alteration of the target locus. To this end, we have designed RISCI - "Repeat Induced Sequence Changes Identifier", a comprehensive comparative genomics based in silico subtractive hybridization pipeline to identify such changes, if exclusive to one of the two genomes being compared. It is modeled on LINEs or Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements (non Long Terminal Repeat retrotransposons) [reviewed in [39]], since they display a wide array of sequence changes upon insertion, such as target site duplication, 3'and 5' flank transduction, deletion of target locus upon insertion, inversion and truncation of repeat sequence during transposition besides post insertion modifications like disruption and recombination [40]. In the test dataset of 302 full length L1HS elements (LINE1- Human Specific) in the reference human genome, RISCI predicted and confirmed 26 human-specific 3' flank transduction events (in comparison with the chimpanzee genome), predicted 14 novel insertion polymorphism (compared to alternate human assemblies - Celera and HuRef), 1 inter element recombination in the human genome resulting in the loss of 13.4 kb of sequence and 4 inter element recombination events in the chimpanzee genome. 42 Human specific 3' flank transduction and at least 24 novel polymorphic insertions, besides several recombination events were inferred from analysis of truncated L1HS retrotransposons. RISCI also predicted 140 novel AluYa5 polymorphic insertions in the reference human genome (in comparison with alternate human assemblies - Celera and HuRef).

Results

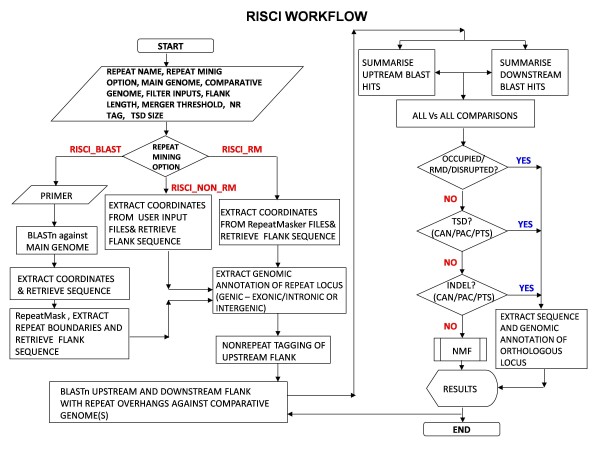

RISCI is a comparative genomics-based pipeline which sequentially picks the transposon loci in one genome ('Reference ' or 'Main' genome), using one of the three repeat mining options (see materials and methods), and precisely zooms into the corresponding orthologous loci in other genome(s) ('Comparative genome(s)') using user defined length of flanks (default 5000 bases) extending 50 bases into the transposon (repeat overhangs) and Blastn [41]. It then infers the nature of alteration either at the transposon locus in the reference genome or the ortholog in the comparative genome(s), based on event specific-alignment signatures (discussed below). The genomic context (intergenic or genic, if genic - exonic or intronic) of the transposon locus in the reference genome and the ortholog in the comparative genome(s) is also integrated by parsing the annotation files, if available. For each transposon locus in the reference genome, RISCI sequentially assesses whether the orthologous locus in the comparative genome is occupied (indicating shared ancestry), has undergone post insertion changes, or is empty. If empty, RISCI infers insertion-associated sequence changes based on the location of target site duplication (TSD - discussed later). If TSD is not found, the orthologous locus is checked for insertion-mediated deletion or parallel independent insertions or insertion deletion at the orthologous locus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RISCI flow chart depicting basic steps of the pipeline. Major inputs include the repeat name (as identified by Repeat Masker), repeat mining option, filter inputs, flank length (default 5000 bases), merger threshold (default 50 bases), size of non-repeat tag (default 500 bases), maximum target site duplication (TSD) size (default 50 bases) and speed options. The genomic annotation of the repeat locus is parsed from the gen bank file if made available. The upstream sequence is tagged with user defined length of non repeat sequence wherever possible (default 500 bases). The upstream and downstream flanks, each carrying 50 base overhang into the repeat, are BLASTed separately against the comparative genome(s) and the BLAST alignment files summarized. For each repeat locus in the main genome, all upstream blast hits are compared against downstream blast hits in the same orientation and sequentially checked for shared ancestry (occupied), post insertion changes (recombination-mediated deletions, disruptions etc.), target site duplication (orthologous locus empty) and classified as CAN, PAC or PTS. If no matches for TSD are found both on the corresponding chromosomal homologue as well as on other chromosomes, the locus is checked for miscellaneous events (INDELs) like insertion-mediated deletion or parallel insertion or insertion deletion on corresponding chromosomal homolog, else the locus is reported as no match found (NMF). In the final results file, RISCI annotation for each locus, genomic annotation of the repeat loci in the main or reference genome and of the orthologous locus in the comparative genome, percentage repeat content of the flanks, Blastn coordinates (query and subject) for the flanks, size of TSD or INDEL or RMD are reported. In case of TSD, sequence of 5' and 3' TSD in the reference genome and of the lone copy of TSD in the comparative genome are also reported.

RISCI was tested on full length (>6 Kb) (Table 1, Additional files 1, 2 and 3) and truncated L1HS elements (Table 1, Additional files 2, 4, 5 and 6) and AluYa5 (Table 1, Additional files 7, 8, 9 and 10) human-specific retrotransposons with the reference human genome [42] as the reference or main genome and the reference chimpanzee [43] and alternate human assemblies, Celera [44] and HuRef [45], as the comparative genomes. RISCI predicted several polymorphic loci in reference human genome comparison with the alternate human assemblies (Additional files 11 and 12). To test the efficacy of RISCI, we present a comparison with the data of Mills et al (Additional file 13) and partially recapitulate a study published earlier by Sen et al [46] (Additional files 14 and 15). Further, to demonstrate that RISCI can handle other transposon classes in other related genomes as well, we present a preliminary analysis checking for presence-absence of IS element (DNA transposon) in various strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Additional file 16). We describe here in details the findings of a study on full length and truncated L1HS and AluYa5 retrotransposons.

Table 1.

RISCI annotates the transposon locus in the main genome or the orthologous locus in the comparative genome into several classes based on specific alignment signatures.

| Data set | L1HS (Full length) | L1HS (Truncated) | AluYa5 (all) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference genome - Reference human genome | Comparative genomes | Comparative genomes | Comparative genomes | |||||||

| Class | RISCI annotation | Chimp | Celera | HuRef | Chimp | Celera | HuRef | Chimp | Celera | HuRef |

| Shared ancestry | OCCUPIED | 1 | 217 | 171 | 274 | 1227 | 1174 | 314 | 3529 | 3334 |

| Post insertion changes | C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD | 1 | 7 | 43 | 16 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED | 4 | 12 | 11 | 32 | 13 | 21 | 90 | 22 | 74 | |

| M_INTRA_RMD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 7 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| C_INTRA_RMD | 0 | 15 | 24 | 10 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Orthologous locus empty | CAN | 170 | 27 | 25 | 426 | 62 | 76 | 3132 | 326 | 420 |

| PAC | 68 | 9 | 10 | 109 | 16 | 22 | 54 | 2 | 4 | |

| PTS | 32 | 3 | 3 | 78 | 12 | 14 | 23 | 2 | 4 | |

| INDELS | INDEL_CAN | 3 | 2 | 7 | 43 | 4 | 6 | 164 | 34 | 79 |

| INDEL_PAC | 6 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |

| INDEL_PTS | 9 | 5 | 5 | 28 | 6 | 3 | 96 | 24 | 53 | |

| Others | TWIN PRIMING | 0 | 0 | 0 | 142 | 17 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | FRAGMENTED | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| NMF | NMF | 8 | 4 | 2 | 203 | 44 | 19 | 165 | 106 | 81 |

| Total | 302 | 302 | 302 | 1421 | 1421 | 1421 | 4056 | 4056 | 4056 | |

1. Full length L1HS elements

302 full length (> = 6 kb) L1HS elements were identified using the RISCI_RM option for repeat mining (See materials and methods). Among these, RISCI identified 100 insertions as genic (all intronic). Unless otherwise stated, the inferences refer to the transposon locus in the reference or main genome (Table 1, Additional file 1).

Inferences based on the orthologous locus in the reference chimpanzee genome

a. Shared ancestry

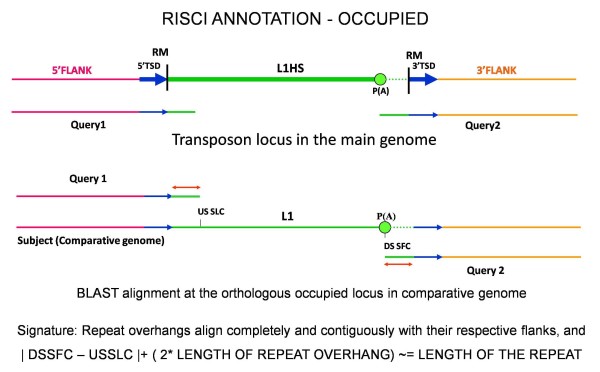

Retrotransposons represent identity by descent markers and are largely homoplasy free [[47] and references therein, [48]]. Therefore, the orthologous locus is considered to have shared ancestry and is annotated as "OCCUPIED" if the repeat overhangs align completely and contiguously with their respective flanks in the comparative genome and the separation between the upstream and downstream flanks is approximately equal (± 100) to the size of the transposon in the reference genome (Figure 2). It is in context to add that the homoplasy free attribute of retrotransposon markers has been questioned occasionally [49,50].

Figure 2.

Alignment signatures for shared ancesstory or OCCUPIED loci in the comparative genome. Complete alignment of the repeat overhangs contiguously with their respective flanks and the separation between the flanks within 100 base range of the transposon length in the main genome. From left to right - Pink line - upstream flank, blue arrows - Target site duplication sequence, Green line - repeat sequence, dotted lines- poly (A) tails, orange line - downstream flank. DSSFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate.

Only 1 locus, L1HS_4_31 (see materials and methods for nomenclature of repeat locus), was found to be occupied in chimpanzee, L1HS being human-specific.

b. Post insertion changes

two major types of post insertion changes are possible viz. recombination and disruption.

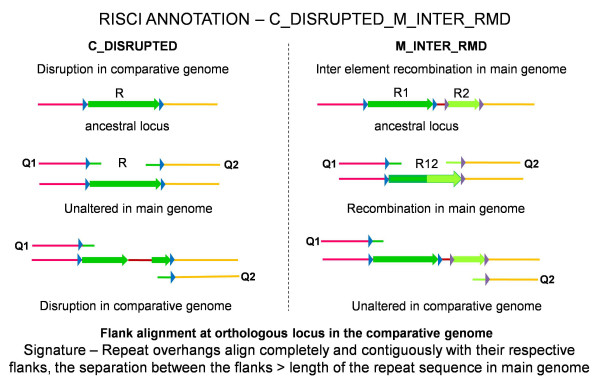

Homology-based recombination between two similarly oriented repeats on a chromosome results in loss of the intervening sequence and one copy of the homologous sequence. The recombination event may be exclusive to the main or reference genome - M_INTER_RMD (Main genome INTER element Recombination Mediated Deletion) or to the comparative genome, C_INTER_RMD (Comparative genome INTER element Recombination Mediated Deletion). In M_INTER_RMD, the repeat overhangs align completely and contiguously with their respective flanks in the comparative genome (assuming that the insertions are not specific to the reference genome), the separation between the flanks is greater than the size of the repeat in the reference genome and the transposon in the reference genome aligns completely (full length) with one of the two transposon copies in the comparative genome (Figure 3). A similar alignment is obtained in case the transposon locus is disrupted in the comparative genome (C_DISRUPTED). However, in this case, the transposon in the main or reference genome does not show full length alignment with any of the two repeats in the comparative genome (Figure 3). Based on the alignment signatures, the locus is annotated as C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD and resolved later by pair-wise blast between the transposon in the main genome and the orthologous locus in the comparative genome. L1HS_4_29c was annotated as C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD, and was shown to be a disruption due to Ns in chimpanzee.

Figure 3.

Alignment signatures for M_INTER_RMD (Inter element recombination in main genome) or C_DISRUPTED (Disruption in comparative genome). In both cases, the repeat overhangs align completely and contiguously with their respective flanks and the separation between Q1 and Q2 is greater than the length of the transposon in the main genome. Left panel - Lone transposon in main genome (R1 - green arrow) disrupted by insertion of exogenous sequence (brown line) in the comparative genome. Q1 - upstream flank with 50 base repeat overhang. Q2 - downstream flank with 50 base repeat overhang. Right panel-From left to right - Pink line - 5' flank of R1, blue triangles - target site duplications of R1, green arrow - first repeat copy (R1), brown line - intervening sequence, grey triangles - target site duplications of R2, light green arrow - second repeat copy (R2 - same color indicating homology), orange line - 3' flank of R2. R12 - recombined repeat with a consequential loss of one copy of homologous region (R2) and the intervening sequence. Note that the 5' TSD of R12 comes from R1 (blue triangle) and the 3' TSD comes from R2 (grey triangle).

Disruptions in main genome are resolved using specific alignment signatures by the RISCI defragmentation module (discussed later). On the other hand, if the repeat overhangs align completely and contiguously with their respective flanks in the comparative genome, but the separation between the flanks is less than the transposon locus in the main genome, the locus is annotated as C_INTRA_RMD (intra-element recombination mediated deletion in comparative genome). No C_INTRA_RMD event was identified in chimpanzee.

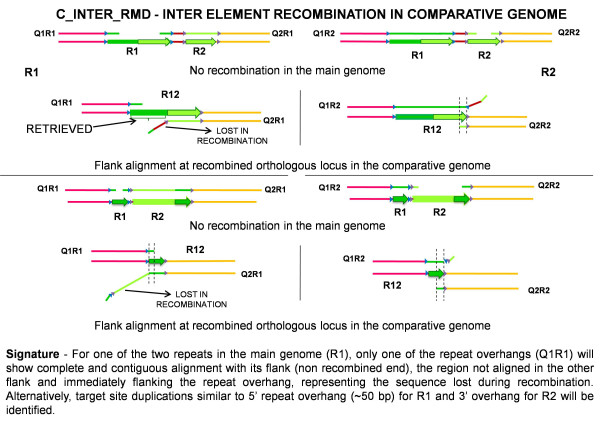

C_INTER_RMD presents more complex signatures. Given sufficient flank length (large enough to span beyond the two repeats in question in the reference genome), such events can also be identified by RISCI. For one repeat in the main genome (R1), only one of the repeat overhangs shows complete and contiguous alignment with the flank (non recombined end). The region immediately flanking the repeat overhang and not aligned in the other flank represents the sequence lost during recombination (Figure 4). For the other repeat (R2), an overlap between upstream and downstream query in the repeat overhang is seen. Alternatively, overlap between upstream and downstream query in the 5' repeat overhang for one repeat, and 3' overhang for the other repeat may also be identified (Figure 4). A disruption specific to the reference genome, the orthologous locus in the comparative genome being occupied and intact also gives a similar signature (Additional file 17, Figure S1). Therefore, RISCI classifies such loci as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED.

Figure 4.

Alignment signatures for C_INTER_RMD (Inter element recombination in the comparative genome). Two possible recombination scenarios and the possible alignments for R1 and R2, which recombine in the comparative genome to form R12 are shown. From left to right - Pink line - 5' flank of R1, blue triangles - target site duplications of R1, green arrow - first repeat copy (R1), brown line - intervening sequence, grey triangles - target site duplications of R2, light green arrow - second repeat copy (R2), orange line - 3' flank of R2. Region of homology between R1 and R2 shown in light green in top panel and dark green in bottom panel, R12 - recombined repeat with a consequential loss of one copy of the homologous region and the intervening sequence. Note that the 5' TSD of R12 comes from R1 (blue triangle) and the 3' TSD comes from R2 (grey triangle). Q1R1 - 5' flank of R1 with 50 bp repeat overhang, Q1R2-5' flank of R2 with 50 bp repeat overhang, Q2R1 - 3' flank of R1 with 50 bp repeat overhang, Q2R2 - 3' flank of R2 with 50 bp repeat overhang. As can be seen from the figure, the flank size should be sufficiently long to span the entire intervening region and other copy of the repeat to pick up such changes.

Contrary to expectations of no C_INTER_RMD events in chimpanzee, 4 such recombination events (L1HS_ 2_14, 3_13, 5_3 and 12_10) were reported with high RISCI scores (refer methods) and low N-scores (%Ns in a sequence). For each of these loci, 5' truncated L1 element was found in close proximity downstream of the transposon locus in the human genome. All retrieved orthologous loci in chimpanzee aligned with the L1HS sequence in the human genome except L1HS_5_3. This sequence was, however, annotated as L1MA9 by RepeatMasker suggesting homology with L1HS sequence. 1586 bases of intervening sequence in L1HS_3_13 were lost in recombination. In the other three cases the recombining repeats were located next to each other.

The fact that an orthologous locus each in chimpanzee was found to be occupied and disrupted and 4 orthologous loci showed recombination suggests that though largely human specific, as evidenced by the large number of empty alleles in chimpanzee, L1HS predate human chimpanzee divergence, as has been reported earlier [51]

c. Inferences based on empty allele at the orthologous locus

Target site duplication (TSD) upon transposon insertion is almost universal [1]. Exceptions include DIRS (Dictyostelium Interspersed Repeats) among retrotransposons [52] and Crypton [53] and Helitron [54] super families of DNA transposons. Loci not found to be occupied or altered post insertion in the comparative genome(s) are then screened for the empty locus using a novel TSD finding strategy.

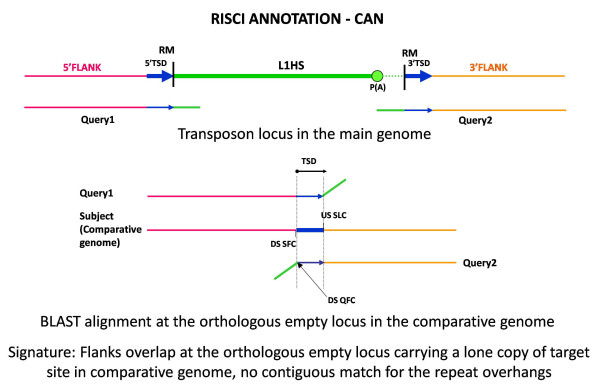

The rationale behind this strategy is that since both the upstream and downstream flanks of the transposon carry the target site duplication sequence, of which only one copy is present at the orthologous empty locus in the comparative genome, when the upstream and downstream flanks are separately blasted against the comparative genome, the flanks would show an overlap in the comparative genome in the region of the TSD (Figures 5 and 6). The TSD sequence is thus used as a clamp to accurately identify the empty orthologous locus in the comparative genome(s). A TSD size of zero is allowed to accommodate endonuclease independent L1 insertions [55] and transposons which do not duplicate target site. RISCI further classifies the transposition event in the reference genome as canonical (excusive mobilization of the transposon sequence) or non canonical (transposition with flank transduction), based on the position of the TSD in the downstream flank. TSDs were identified for 270 loci in chimpanzee.

Figure 5.

Alignment signature for CAN (canonical transposition). Query1 and Query2 show an overlap in the region of target site duplication at the orthologous empty locus, while the repeat overhangs do not align (represented by oblique green lines) and DSQFC is < 71 or A and AT score > 0.65 or 0.90 respectively. From left to right - Pink line - upstream flank, blue arrows and line - target site duplication sequence, green line - repeat sequence, dotted lines- poly (A) tails, orange line - downstream flank. DSQFC - downstream sequence query first coordinate, DSSFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate.

Figure 6.

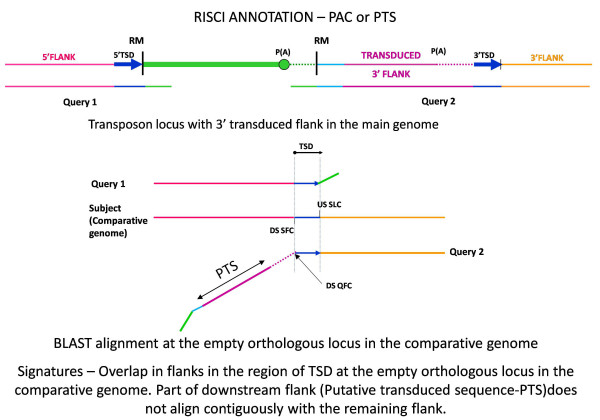

Alignment signatures for PAC and PTS. Query 1 aligns at the orthologous empty locus starting from the TSD upwards. Likwise, Query 2 aligns from the TSD, downwards. The region of Query 2 preceding the TSD (represented by oblique line), which does not find a contiguous match, consists of the 3' repeat overhang and the misannotated poly A tail or the transduced flank depending on the A and AT scores. From left to right - Pink line - upstream flank, blue arrows and line-target site duplication sequence, green line - repeat sequence, dotted lines- poly (A) tails, dark pink line - transduced flank, orange line - downstream flank. DSQFC- downstream sequence query first coordinate, DSSFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, PTS - putative transduced sequence, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate.

Canonical transposition

The 3' end of non LTR retrotransposons are generally under or overestimated by RepeatMasker since they end in highly variable poly-A tails. To accommodate this anomaly, even if the TSD is found 20 bases downstream of the RepeatMasker annotated 3' end, the retrotransposition event is annotated as CAN (Canonical). 170 loci in the reference human genome were annotated as CAN (Figure 5).

Additionally, the RNA transcription machinery occasionally skips the retrotransposon's weak polyadenylation signal resulting in a readthrough transcript. This transcript when subsequently integrated at another locus effectively duplicates the original 3' flank to the extent of the readthrough [56-58]. This mechanism may lead to exon shuffling [58,59] and gene duplication [60]. Therefore, in non-LTR retrotransposons where the TSD is found beyond 20 base pairs of the RepeatMasker annotated 3' end, the unmatched region beyond the repeat overhang till the beginning of the TSD may either represent a grossly misannotated poly-A tail or a true 3' transduced flank (Figure 6).

If the A-score (∑A/length of unmatched downstream sequence) > 0.65 or AT-score (∑(A+T)/length of unmatched downstream sequence) is > 0.90, the transposition is annotated as PAC (Poly A Canonical-canonical transposition with a grossly misannotated poly A tail). The score thresholds were fixed on the basis of empirical observations and may be reset by the user. 68 Loci were annotated as PAC. It is important to restate here that both CAN and PAC represent canonical insertions (exclusive mobilization of transposons sequence). RISCI thus precisely defines transposition boundaries in the reference genome if the orthologous locus is empty in the comparative genome, providing an improvement over RepeatMasker annotations (Additional file 17 Figures S2 and S3). The remaining 32 loci, for which TSDs were identified, qualify as putative 3' flank transduction events and are annotated as PTS (loci with Putative Transduced Sequence, Figure 6).

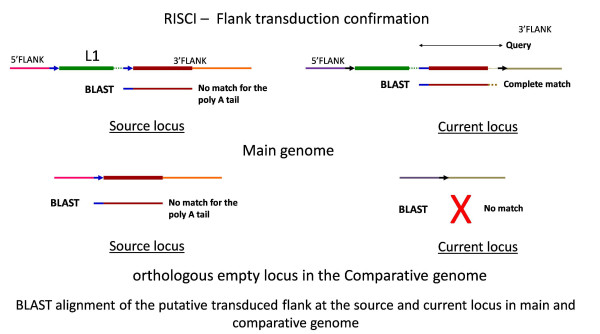

3' flank transduction

RISCI has inbuilt confirmation module for 3' flank transductions. A putative transduced flank is confirmed as a true transduction event when it has at least two non-redundant Blast high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) in the reference genome - one from where the sequence is picked - target or current locus (complete match), and the other from where it has moved to the target locus - source locus (partial - no match for the polyA tail), and/or one hit (partial) in the comparative genome on the chromosomal homolog corresponding to the source locus in the reference or main genome (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Signatures of true 3' flank transduction. The source locus in the main genome consists of an L1 element with TSDs (blue arrows) which moves to the target or current locus along with a part of the 3' flank (brown bold line) forming new TSDs (black arrows). In contrast, no flank transduction takes place in the current locus in the comparative genome. As indicated, the query consists of one copy of the original TSD (blue line), the transduced flank (brown bold line) and the second poly A tail (dotted brown line). When blasted on the main genome, at least two hits are obtained - one complete match at the current locus and one almost complete match (barring the poly A tail) at the source locus. In the comparative genome, no match is found at the orthologous current locus (since no transposition event has taken place for lack of L1 element at the source locus as shown here, or otherwise). The match at the source locus in the comparative genome is similar to the match at the source locus in the main genome and on corresponding chromosomal homologue. RISCI has an inbuilt module for 3' flank transduction confirmation which enlists the putative transduced sequence, the number of blast hits obtained in the main and comparative genomes and the most probable source locus in the two genomes in case multiple hits are obtained. From left to right - Pink line - 5' flank at the source locus, blue arrows - TSDs at the source locus, green line - repeat, dotted line - poly A tail, brown and orange lines - 3' flank at the source locus, purple line - 5' flank at the current locus, black arrows - TSDs at the current locus, grey line - 3' flank at the current locus.

Of the 32 loci predicted as PTS, the source locus was unambiguously identified for 23 both in the main genome and the comparative genome. For another 3 (L1HS_5_18c, 9_8 and 18_10), the source locus in human was clear and the only hit in chimpanzee was partial but on the chromosome corresponding to the identified source locus in the main genome. The source locus for L1HS_7_14 in chimpanzee is ambiguous. No matches in chimpanzee were found for L1HS_1_24c. The A-score or AT-score of L1HS_4_22, L1HS_18_7 and L1HS_X_9c were very close to the threshold and actually represent misannotated poly-A tails. L1HS_8_6c is falsely reported as PTS. The length of the confirmed transduced flanks ranged from 50 bp to 1600 bp. (Additional file 2).

5' flank transductions

5' flank transductions occur when a strong upstream promoter drives transcription into the L1 sequence. In such cases the 5' TSD is found slightly upstream of the actual L1 5' end. Template switching [61-63] may also result in formation of 5' TSD upstream of the transposon 5' end. Of the 12 reported 5' flank transductions by RISCI, 4 (L1HS_ 7_11, 11_10c, 15_1c and X_19c) were found to satisfy flank transduction criteria (mentioned earlier) and represent confirmed 5' flank transductions (Additional file 3). In the remaining cases, the putative transduced flank was a repeat sequence with multiple hits and may have come to occupy the current locus either as a consequence of 5' flank transduction or insertion into the 5' end of L1. The possibility of template switching is minimal since L1 reverse transcriptase is known to have low processivity.

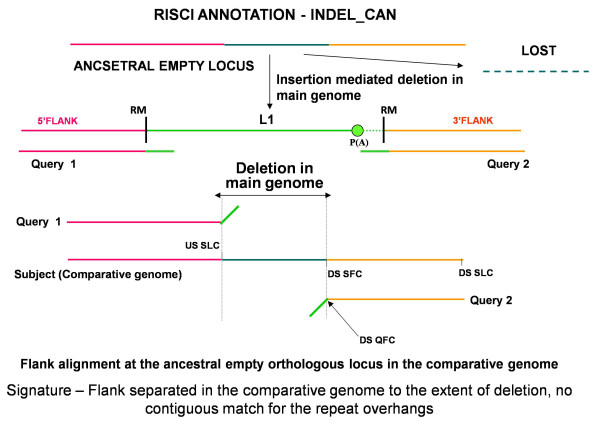

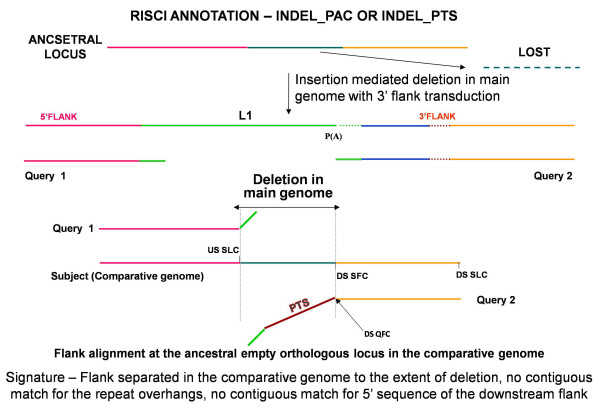

c. Insertion-mediated deletion or parallel independent insertions or insertion-deletions

Retrotransposons like L1s and Alus have been reported to occasionally cause deletions at the target site in cell culture assays as well as by comparative genomics approaches [64-66]. Additionally, though rare, parallel independent insertion at the same locus in the comparative genome is also possible [67,68]. The orthologous locus may also undergo independent changes (insertion, deletions or gene conversions). In all cases the upstream and downstream flanks in the comparative genome are separated from each other by the extent of deletion or parallel insertion or other changes and the repeat overhangs do not align contiguously with their respective flanks (Figures 8 and 9) as opposed to recombination.

Figure 8.

Alignment signatures for Insertion-mediated deletion with exclusive mobilization of the transposon. Insertion-mediated deletion results in replacement of original sequence by the transposon without the duplication of target site. On alignment at the orthologous locus in the comparative genome, no match is found for the repeat overhangs (represented by oblique green lines) and the upstream and downstream flanks are separated by a sequence stretch representing the original sequence lost upon insertion of the repeat in the main genome. Ancestral locus - from left to right - Pink line - 5' flank, turquoise line - sequence lost on L1 insertion, orange line - 3' flank. DS QFC - downstream sequence query first coordinate, DS SFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate.

Figure 9.

Alignment signatures for insertion-mediated deletion concurrent with 3' flank transduction. Ancestral locus - from left to right - Pink line - 5' flank, turquoise line - sequence lost on L1 insertion, orange line - 3' flank. Green line - repeat sequence, brown line - transduced sequence, dotted lines - poly A tails. DS QFC - downstream sequence query first coordinate, DS SFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate. Insertion mediated deletion results in replacement of earlier sequence by the repeat with transduced flank (brown line) without the duplication of target site. On alignment at the orthologous locus in the comparative genome, no match is found for the repeat overhangs (represented by oblique green lines) and the transduced sequence, and the upstream and downstream flanks are separated by a sequence stretch representing the sequence lost upon insertion of the repeat in the main genome. Depending on the A and AT scores of the unmatched portion of the downstream flank, RISCI annotates the locus as INDEL_PAC or INDEL_PTS.

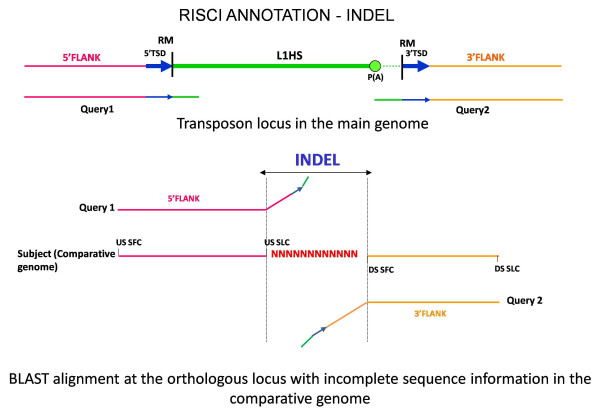

As in normal transposition, insertion-mediated deletions may result from a normal (CAN) or 3' misannotated (PAC) or readthrough transcript (PTS). Hence INDELs are sub annotated as INDEL_CAN (Figure 8), INDEL_PAC and INDEL_PTS (Figure 9), depending on how far from the annotated 3' end of the repeat does the match for the downstream flank starts. Most INDEL predictions by RISCI are a consequence of substitution of actual sequence by an estimated number of Ns (Figure 10). If the N-score is less than 10 and the locus annotated as "INDEL_PTS", the PTS is also retrieved and confirmed as in normal 3' flank transduction.

Figure 10.

Misannotation because of sequencing gaps. Since a certain amount of sequence information at the orthologous locus is missing and substituted by approximate number of Ns, only partial matches for the upstream and downstream sequences are obtained resulting in false annotation by RISCI. From left to right - Pink line - upstream flank, blue arrows - Target site duplication sequence, Green line - repeat sequence, dotted lines- poly (A) tails, orange line - downstream flank. DSSFC - downstream sequence subject first coordinate, Query1 - 5' or upstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, Query2 - 3' or downstream flank with 50 bp repeat overhang, RM - RepeatMasker start and end coordinates, USSLC - upstream sequence subject last coordinate.

It is important to mention that though annotated only after exclusion of all other possibilities and two rounds of check, INDEL annotations per se have relatively relaxed criteria of the flanks being separated by a maximum of 10000 bases and at least a 1000 base query coverage in case of INDEL_PTS. Given the high repeat content of the flanks, random matches may not be ruled out. User discretion is, therefore, advised while dealing with INDELs and INDEL_PTS in particular.

18 INDELS were reported. Of these, 9 had N-scores approximately greater than 10 (ranging from ~ 9.22 to 100) or N-stretch at the 3' end (L1HS_9_1c) of sequence, resulting in misannotation. TSDs were not found in the reference genome (checked by blast2 between 500 bp of upstream flank and 2500 bp of downstream flank) for L1HS_10_9c, 12_8c, 18_9c, 20_2 and 22_2c leaving only two possibilities. The indel sequences either represent the sequences deleted during L1 insertion in human or the intervening sequence between two L1s which recombine to form the present L1 in the main genome. In comparison with Celera and HuRef genomes, L1HS_18_9c was definitively identified as M_INTER_RMD (recombined L1 in the main genome). The fact that the intervening sequence in Celera and HuRef genomes showed high similarity with the INDEL sequence in the chimpanzee genome unambiguously suggests that this sequence is ancestral to human specific L1 insertions and the subsequent recombination. The other four loci were either non differential (OCCUPIED) in Celera and HuRef genomes or had high N-scores and hence cannot be definitively classified as insertion-mediated deletions.

TSDs were identified in the reference genome (checked by blast2 as above) for L1HS4_3c, 4_19c, 7_7 and 10_1 immediately before and after the transposon. Intriguingly though, both L1HS_4_19c and 7_7 were annotated as INDEL_PTS by RISCI and the flank transductions were confirmed (Table 2). This might just be coincidental. However, the fact that the only blast hit in chimpanzee corresponds to the source locus chromosome in the human genome and that the sequence carries a poly A-stretch for which no match is found at the source locus in both human and chimpanzee genomes unambiguously links the transposition of this sequence with the preceding L1HS. This is suggestive of an insertion-mediated deletion mechanism with duplication of the target site in the main genome. It is important to note here that both L1HS4_19c and L1HS7_7 are insertions into intronic region of genes HSD17B11 (alias DHRS8) and AUTS2 respectively.

Table 2.

Target and source locus for the 3' transduced flank in the main (human) and comparative genomes (chimpanzee) for loci annotated as INDEL_PTS

| GENOME | LOCUS | L1HS | CHR | CONTIG | ORIENT | QFC | QLC | SFC | SLC | Source-Genic/Intergenic (based on CDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human | Target | L1HS_4_19c | 4 | NC_000004 | Minus | 1 | 91 | 88487299 | 88487209 | |

| human | Source | L1HS_4_19c | 4 | NC_000004 | Plus | 16 | 91 | 88496516 | 88496591 | HSD17B11, INTRON 5 |

| Chimp | Source | L1HS_4_19c | 4 | NC_006471 | Plus | 16 | 91 | 90265309 | 90265384 | DHRS8, INTRONS 4,5 |

| human | Target | L1HS_7_7 | 7 | NC_000007 | Plus | 1 | 619 | 69306280 | 69306898 | |

| human | Source | L1HS_7_7 | 5 | NC_000005 | Minus | 3 | 606 | 140466972 | 140466369 | Intergenic |

| Chimp | Source | L1HS_7_7 | 5 | NC_006472 | Minus | 3 | 606 | 142876752 | 142876149 | Intergenic |

RISCI confirmation of 3' flank transduction concurrent with insertion mediated deletion (INDEL_PTS) by unambiguous identification of the source locus in main and comparative genomes. As expected, no hit is found for the target locus in the comparative genome, and one to one chromosomal correspondence for the source locus in main and comparative genome is noticed. Also the source locus hit both in the main genome and in the comparative genome is shorter than the target hit since no match is found for the poly A tail at the source locus. CHR - chromosome, ORIENT - orientation, QFC - Query first coordinate, QLC - Query last coordinate, SFC - Subject first coordinate, SLC - Subject last coordinate. Source loci found within genes (and within exons or introns if CDS coordinates are available are also reported). HSD17B11 and DHRS8 are aliases of eachother.

Inferences based on comparisons with Celera and HuRef genomes

In contrast to the chimpanzee genome, 217 loci in the Celera and 171 in the HuRef genome were annotated as OCCUPIED. Among these, 149 loci were commonly occupied in all 3 human genomes representing the more ancestral or fixed loci. 57 Of these were insertions into genes. Though not informative for phylogenetic studies, some of these may have evolutionary significance. TSDs were identified for 39 elements in Celera and 38 in HuRef assembly comparisons (Table 1). These represent recent and, therefore, polymorphic insertions in the human genome, amenable to phylogenetic studies. Of these, 27 in Celera and 25 in HuRef were canonical insertions in the reference human genome, 9 in Celera and 10 in HuRef had misannotated poly A tails (PAC) and 3 each were annotated as PTS (3' flank transduction). All the 3 PTS in Celera and 2 in HuRef were confirmed by RISCI. As mentioned in comparison with chimpanzee (Additional file 2), X_9c in HuRef has A-score (0.61) close to the threshold (0.65). 5' flank transduction was predicted for L1HS _1_5c, 4_35 and 15_1c both in Celera and HuRef, and the source locus was unambiguously identified for L1HS_15_1c both in Celera and HuRef (Additional file 3). Multiple hits were obtained for the other two, both in reference and comparative genomes.

7 C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD were reported in comparison with the Celera genome, of which L1HS_18_9c is M_INTER_RMD, with full length L1s at the 5' and 3' end at the orthologous locus in both Celera and HuRef resulting in loss of 13.8 kb of sequence (6 kb L1HS and 7.8 kb of intervening sequence). Additional L1 sequence was found at the 5' end of L1HS_1_6 (N-score - 0.3) and 3' end of L1HS_11_6 (N-score -0). These may be true insertions into pre-existing repeats. Others had very high N-scores. Of the 12 C_INTER_RMD reported, only 5 had N-score < 10, 3 of which had Ns either at the 5' or 3' end of the sequence. For the remaining 2 (L1HS_5_15 and 16_2C), Ns were strategically located at the 3' (L1HS_5_15) or 5' (L1HS_16_2c) end of partial L1 sequence, followed by partial duplication of the upstream (L1HS_5_15) or downstream (L1HS_16_2c) sequence in the ortholog, clearly suggesting errors in assembly. 15 C_INTRA_RMD were reported in Celera genome. 4 had N-score less than 10, and two of these (L1HS_2_16 and L1HS_6_2) were less than 5000 bases (full length L1 is 6 kb) and may represent true intra element recombination. 8 INDELS are reported in comparison with Celera genome. Only 1 had low N-score (0) and represents an occupied locus misannotated as INDEL because of partial match for the 3' repeat overhang.

43 C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD were reported by RISCI in the HuRef assembly. L1HS_18_9c (N-score 1.1), as mentioned earlier, is a recombined L1 in the human genome with clear full length L1s at either end. All others, except L1HS_11_6, appear to be a consequence of assembly errors. Even when the N-scores were lower than 0.5 (L1HS_ 1_3, 1_18c, 1_25c, 4_27, 5_18c, 5_23c, 6_7, 7_1, 13_7c, 16_2c, 16_4c and 17_1), no non L1 sequence was reported by RepeatMasker and there was a distinct overlap in the L1 sequence before and after the N-stretch pointing to problems in assembly. L1HS_11_6 appears to have been disrupted by insertion of a truncated L1 sequence in the opposite orientation.

11 C_INTER_RMD are reported in HuRef. 8 Of these had N-scores > 10 or N-stretch at the 5' or 3' end of the retrieved sequence. As in the Celera assembly, the N-stretch is placed next to the partial L1HS sequence, followed by duplication of the upstream sequence in L1HS_4_4, 5_15 and 10_1, indicating errors in assembly. 24 C_INTRA_RMD were reported in HuRef. Only three (L1HS_3_13, 7_9 and 11_1) of these were less than 5000 bases, had low N-scores and may possibly be true intra element recombinations.

13 INDELs were reported in the HuRef assembly. Of these, 9 either had N-score >10 or had N-stretch at the 5' (L1HS_ 8_6c) or 3' end (L1HS_ 8_5 and 12_9) of the indel sequence. L1HS_1_2c, 1_11 and 13_8c represent occupied loci but are classified as INDEL because of partial or no match for the 3' repeat overhang, possibly because of the decay of the poly-A tail or the 3' target site duplication. L1HS_11_11 presents an interesting case. In the HuRef genome, it is annotated as 9 bp (N-score 0.0) INDEL with almost full query coverage for upstream and downstream flanks. However, in the chimpanzee genome the orthologous locus is annotated as CAN with a TSD of 18 bp, which suggests that L1 insertion-mediated deletion of the ancestral locus did not take place and that the orthologous empty locus in the HuRef genome has undergone independent changes.

2. Analysis of truncated repeats

Retrotransposons get truncated in several ways e.g. 5' truncation because of low processivity of reverse transcriptase and competition by RNAse H in LINES, twin priming [69] resulting in loss of intermediate sequence and inversion of the 5' end, looping of m RNA resulting in loss of intermediate sequence without inversion of the 5' end [65] etc. Besides, false truncations may also result from disruption of the full length insertions. True truncations and disruptions pose stiff challenges to repeat detection and annotation programs. The two parts of a disrupted transposon may frequently get annotated as different repeats and small truncated repeats may escape detection or be misannotated [70]. RISCI has special modules for analysis of such repeats.

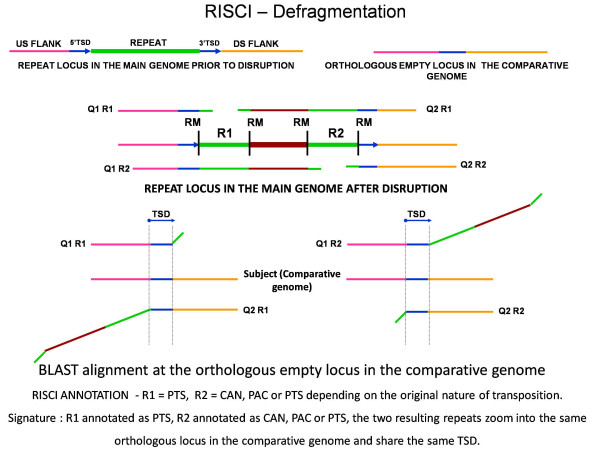

a. Defragmentation module

Defragmentation refers to the identification of the constituent parts of a disrupted or partially deleted repeat in the genome. All disrupted or partially deleted parts of a parent repeat would be in the same orientation, annotated as independent repeats by RepeatMasker, and the target site duplication would be located at the first (5' end) and the last fragment (3' end) of the disrupted repeat. If the orthologous locus in the comparative genome is empty, the upstream and downstream flanks for each fragment would show an overlap in the region of the single copy of the TSD in the comparative genome (Figure 11). In case of a parent repeat fragmented into two, the first half would be annotated as PTS (false annotation) and the second half as CAN, PAC or PTS (depending on mobilization of exclusive repeat sequence or also of the 3' flank) by RISCI and the two would share the same TSD (Figure 11). In the final results file, names of all fragments of a disrupted repeat are concatenated and marked by "!" suffix. As can be seen, the flank length is crucial to read these signatures and only small disruptions can be identified in this manner. To identify large disruptions, blast HSPs of the upstream flank of a repeat locus, for which no annotation is assigned by RISCI, are compared with the blast HSPs of the downstream flanks of all repeat loci in the same orientation downstream of this locus to check for the TSD in the comparative genome. RISCI identified 14 repeat disruptions in the reference genome (Additional file 4) in the analysis of truncated L1HSs (< 6000 bases-reference human genome Vs chimpanzee genome).

Figure 11.

Alignment signatures for defragmentation by RISCI. The original repeat is disrupted into R1 and R2 due to insertion of an exogenous sequence (brown bold line). Blastn alignments for R1 and R2 at the orthologous empty locus in the comparative genome are shown. Query 2 of R1 (Query2 R1), starting from R1 and downstream, consists of the 50 base overhang into the 3' end of R1, the exogenous sequence (brown line), R2, 3' target site duplication and its downstream flank, of which, only the TSD and its downstream flank find a match at the orthologous empty locus (parallel lines) resulting in PTS annotation for R1. For R2, starting from R2 upstream, Query 1 (Query1 R2) consists of 50 bp overhang into 5' end of R2, the exogenous insertion, R1, 5' TSD and its upstream flank, of which only the TSD and its upstream flank find a match at the orthologous empty locus (parallel lines). RISCI annotation of R2 depends on the nature of the original transposition event and RepeatMasker estimation of the 3' end of repeat (CAN, PAC or PTS). The flank length is crucial in indentifying such events and must be long enough to span the exogenous sequence, R1 or R2 and their respective flanks. From left to right - pink line - 5' flank of the original repeat before disruption, blue arrows and lines - TSDs, R1 - first fragment, brown bold line - exogenous insertion, R2 - second fragment, orange line - 3' flank of original repeat. Query1 R1 - upstream flank of R1 with 50 base overhang into R1, Query2 R1, downstream flank of R1 with 50 base overhang into R1, Query1 R2 - upstream flank of R2 with 50 base overhang into R2, Query2 R2 - downstream flank of R2 with 50 base overhang into R2, TSD - target site duplication sequence.

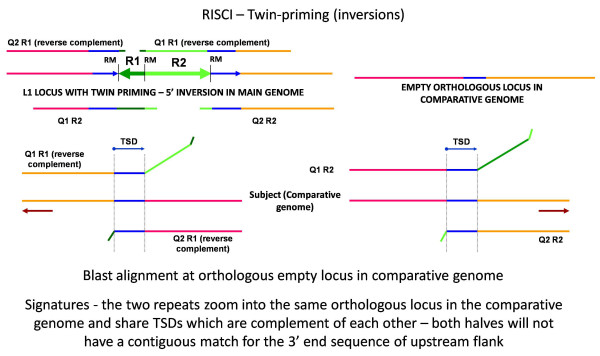

b. Identifying inversions using RISCI

Owing to twin priming [69], LINE insertion may result in inversion of the 5' end sequence and truncated insertions. In such cases, the 5' end is in opposite orientation to the 3' end and each is annotated as a separate repeat by RepeatMasker. The two repeats share the same TSD (in opposite orientations) at the orthologous empty locus in the comparative genome and show an alignment similar to 5' flank transduction (Figure 12). In the final result file names of the elements of a twin priming event are concatenated and suffixed by "*". 142, 17 and 24 twin priming events were identified in the reference human genome when compared to chimpanzee, Celera and HuRef genomes, respectively. As expected, no twin priming was reported in AluYa5 comparisons since probability of a twin priming event is directly proportional to the length of the template.

Figure 12.

Alignment signatures for twin priming. Twin priming results in inversion of the 5' end of L1 (R1) as opposed to its 3' end (R2), the arrowheads indicating opposite orientations. Since Query1 R1 and Query2 R1 are in opposite orientation to Query1 R2 and Query2 R2, the alignment of query sequences at the orthologous empty locus in the comparative genome is in opposite orientations (indicated by opposite facing brown arrows). Also for Query1 R1, no match is found for 50 base overhang into R1, and the R2 sequence. Similarly, for Query1 R2, no match is found for 50 base overhang into R2, and the R1 sequence. Since the alignments are in opposite orientations, the TSDs identified are reverse complements of each other. From left to right - Pink line - 5' flank of the repeat, blue arrows and lines - target site duplication sequence, R1 - inverted 5' sequence, R2 - normal 3' sequence, orange line - 3' flank of the repeat. Query1 R1 - upstream flank of R1 with 50 base overhang into R1, Query2 R1, downstream flank of R1 with 50 base overhang into R1, Query1 R2 - upstream flank of R2 with 50 base overhang into R2, Query2 R2 - downstream flank of R2 with 50 base overhang into R2. In the final result file, inversions are indicated by '*' suffixed to the repeat name.

It may be noted that since both disruptions and twin priming events are identified in a secondary screening based on the primary annotations by RISCI, misannotations are possible if one of the two constituents of a disruption or twin priming event is not annotated to the same repeat class by RepeatMasker.

2.1 Truncated L1HS analysis

A total of 1421 truncated L1HS elements (< 6 kb) were mined by RISCI in the reference human genome by using the RISCI_RM option (direct parsing of repeat coordinates from pre-masked files). However, 1421 does not represent the true number of truncated L1HS elements in the human genome. Twin primed L1HS elements are counted as two despite being the constituent parts of a single parent. Likewise, disrupted L1HS elements are also counted twice. On the other hand, some of the truncated L1HS elements may escape detection or may be misannotated as L1HS. Unless otherwise stated, the inferences refer to the transposon locus in the reference or main (reference human) genome (Table 1, Additional files 4, 5 and 6).

Inferences based on the orthologous locus in the reference chimpanzee genome

a) Shared ancestry

274 loci were found to be occupied at the orthologous loci in chimpanzee. This partly reflects the problem of truncated repeat misannotation, as also the fact that L1 insertions may not be truly human-specific. Most repeat annotation programs rely on homology to consensus sequences and characteristic nucleotides substitutions to classify a given repeat into a particular class and subclass. However, in the case of truncated repeats the quality of annotation is compromised for lack of sequence information, frequently leading to misannotation. This becomes strikingly evident in the case of twin priming and repeat disruption events, where constituent parts of the same repeat are assigned to different subclasses.

b) Post insertion changes

Both recombination and disruptions were reported by RISCI. The details may be referred to in Additional files 1 and 2. 16 C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD events were inferred on the basis of alignments obtained at the orthologous loci in chimpanzee. Since the RepeatMasker files for both reference human and reference chimpanzee genomes were available, we pulled out the repeat annotations for the locus and its flank in the human genome and the identified ortholog and flanks in the chimpanzee genome to confirm recombination (Additional file 1). For example, Y_31c represents a perfect case of inter element recombination in the human (reference or main) genome (M_INTER_RMD) and preservation of the ancestral locus in chimpanzee. The orthologous locus in chimpanzee has no Ns and partially homologous sequences at the 5' and 3' ends (Figure 13, Additional file 2). The recombination between the two results in loss of 11,354 bases in the human genome.

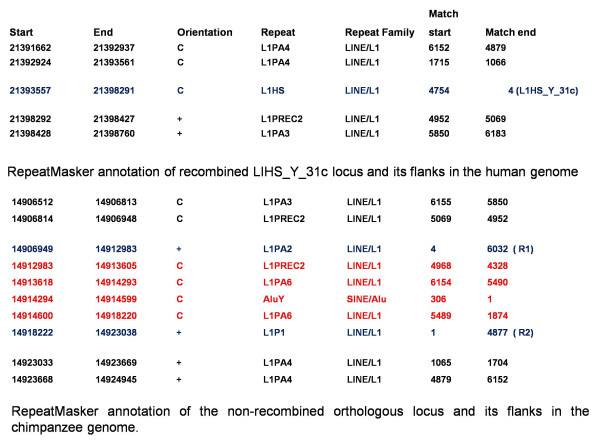

Figure 13.

Repeat Masker annotations for the recombined locus in the human genome and the original non-recombined ortholog in chimpanzee - Please note that the ortholog in chimpanzee was identified in the opposite orientation and should therefore be read in reverse direction when comparing with the human locus. Loci marked as R1 and R2 (in blue) in chimpanzee annotation represent the loci that recombine in the human genome to give rise to the Y_31c locus. The region marked in red represents the intervening sequence lost in recombination.

N-scores ranging from 0.36 to 8.11 were found for the remaining 11 loci. L1HS_1_28, 1_40, 8_35, 9_25, 11_17c, 14_35 and 18_38 also represent M_INTER_RMD. In each of the above cases, stretches homologous to the repeat locus in the reference genome were present at 5' and 3' ends of the identified ortholog, and recombination resulted in the loss of one copy equivalent of the homologous sequence and the intervening sequence. However, in most of these cases (except L1HS_9_25 and 18_38) Ns were strategically located in between the two potential homologous stretches of L1s in chimpanzee which recombine to form the lone L1 in the human genome. L1HS 9_25 and 18_38 result from recombination between distant L1s leading to loss of more than 5 kb of intervening sequence.

L1HS_11_4 on the other hand represents minor disruption (C_DISRUPTED) of the orthologous locus in the chimpanzee genome. L1HS_4_84c, 7_73 and 11_4 represent occupied loci in chimpanzee, but are annotated so because of overrepresentation of Ns and misannotation of boundaries by RepeatMasker. L1HS_17_2 is doubtful. The remaining 4 (L1HS 2_72c, 5_46c, 7_29 and X_63c) had N-scores greater than 10 and were not considered further.

32 C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED events were identified in chimpanzee of which 9 (L1HS 1_61, 1_63, 3_17c, 6_19c, 6_41, 7_21, 8_19, 16_16c and 19_12c) were found to be true inter element recombination events in chimpanzee (C_INTER_RMD). On closer inspection, another 14 loci were found to be disrupted in the human (reference) genome (M_DISRUPTED), with only one of the two fragments annotated as L1HS (except 13_34c and 13_35c). These include L1HS 1_45, 3_7c, 3_57, 4_59, 4_114c, 4_130c, 4_134, 5_54c, 6_38, 6_71, 7_67, 12_31c, 13_34c and 13_35c. Alu element insertion into the parent L1 was the most common cause of disruption. Intriguingly, Alu showed preferential insertion around 300 bases starting from the 5' end of L1. L1HS_6_38 harbors an SVA insertion. Three (L1HS 6_56, L1HS 7_52 and 8_32c) of the identified orthologs had high N-scores. The orthologous loci for 16_11 and X_85 are actually occupied but were annotated so since no contiguous match is found for one of the two repeat overhangs. The remaining 5 loci, L1HS2_3c, 3_14c, 14_20 and 16_24 are difficult to explain. L1HS_2_3c may be a result of parallel independent insertions. L1HS_3_14c is annotated as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED in Celera and HuRef comparisons as well and the separation between the flanks is identical. There is homologous L1 sequence in the opposite orientation immediately downstream where recombination may have taken place in these genomes to give rise to the present ortholog. The ortholog for 14_20 has N-stretch at its 3' end, confounding the analysis and, 16_24 locus in the human genome has several Alus inserted into an L1 cluster. The ortholog in chimpanzee is also similar.

10 orthologs were annotated as C_INRA_RMD. L1HS_3_24c presents a picture perfect C_INTRA_RMD event. The identified ortholog has no Ns in the chimpanzee genome. The L1 locus in the human genome is annotated as

36637972 36641523 C L1HS LINE/L1 (1) 6154 2621

The RepeatMasker annotation for the orthologous locus in chimpanzee is

37462397 37462754 C L1PA3 LINE/L1 (0) 6155 5837

37462759 37462898 C L1P1 LINE/L1 (3397) 2749 2611

This clearly suggests intra element recombination resulting in the loss of 3076 bases of L1 sequence in chimpanzee. Orthologs for L1HS 2_15, 4_51, 10_30c, 14_31, 15_23 and X_45c had low N-scores but the breakpoint was located in Ns. If the Ns are truly representative, these represent true intra element recombination events. L1HS_3_10, X_96 and X_105 had N-scores > 10 and were discarded.

Another 32 loci were annotated as M_INTRA_RMD (Intra element recombination mediated deletion in the reference or main genome). 6 of these had N-score greater than 10 and were not considered. L1HS_4_5 (N-score-0) presents a perfect M_INTRA_RMD event. The RepeatMasker annotation for the complete locus in the human genome is -

13409700-13411042 + L1HS LINE/L1 1 1334 (L1HS_4_5)

3411031-13415298 + L1PA3 LINE/L1 1901 6168

And the identified orthologous locus in chimpanzee is annotated as -

13672242 13678285 + L1PA3 LINE/L1 1 6045

This very clearly suggests that the ancestral full length insertion in the human genome has undergone intra element recombination resulting in loss of intervening sequence between regions of micro-homology and producing 2 truncated elements, only one of which is annotated as L1HS. Similarly, L1HS_3_118, 3_88c, 4_4c, 4_129, 7_19c, 8_5 and 13_18 have N-scores of 0 and represent confirmed M_INTRA_RMD loci. L1HS_10_39 and 11_25 represent special cases where the recombined locus has further undergone disruption in the human genome, while full length L1 element is conserved in chimpanzee. Ns were found at the breakpoint for L1HS_1_13, 1_48, 3_54, 3_83, 9_44, 10_29c, 16_23 and 18_22, confounding the analysis. L1HS_3_20c, 4_52, 5_52, 5_93c, 8_50c and 12_11 are falsely reported as M_INTRA_RMD and are probably parallel independent insertions.

c) Inferences based on empty allele at the orthologous locus

TSDs were identified for 763 loci. Among these, 138 were annotated as twin priming events and 12 were annotated as disruptions. Thus, effectively 613 empty orthologous loci were found in chimpanzee. These were further subdivided into three classes based on the position of the 3' TSD and sequence composition of the stretch between the annotated 3' end of L1 and start of the 3' TSD.

Canonical transposition

426 (of 613) loci in the reference human genome were annotated as CAN - exclusive mobilization of the transposon sequence (Figure 5). Another 109 loci were annotated as PAC (Canonical with a misannotated 3'end, Figure 6).

Non-canonical transposition (3' flank transduction)

The remaining 78 loci qualified as putative 3' flank transduction events and were annotated as PTS (loci with Putative Transduced Sequence). The source locus was unambiguously identified for 42 both in the human and chimpanzee genomes. The source locus was clearly identified in the human genome for L1HS_3_80, 11_43 and 15_1 but no matches were found in the chimpanzee genome. Another 13 loci, (L1HS_1_103, 2_43, 3_26, 5_3, 9_22, 11_11c, 11_34, 12_7, 14_28, 20_19, 21_12, X_50 and X_97), represent twin primed or disrupted L1s in the human genome for which only one of the two constituents is annotated as L1HS by RepeatMasker, leading to misannotation by RISCI. For another 4 (L1HS_2_51, 5_61, 8_40 and X_60) matches were not found for one of the two constituent halves leading to misannotation by RISCI. The A-score and/or AT-score of L1HS_1_58, 1_75, 1_79, 4_21, 4_93 and 9_45 were very close to the threshold and represent marginally misannotated poly-A tails. The PTS was very small for X_84 (20 bases). The PTS for another 6 (L1HS_1_29, 2_32, 2_45, 4_33, 7_24c, X_33) was repeat rich preventing identification of the source locus. The remaining 2 (L1HS_3_39 and 5_22c) are misannotated as PTS by RISCI. The length of the confirmed transduced flanks ranged from 30 bp to 2100 bases (Additional file 2).

Insertion-mediated deletion or parallel independent insertions or insertion-deletions

86 INDELS (43 INDEL_CAN, 14 INDEL_PAC and 28 INDEL_PTS) were reported. Of the 44 loci annotated as INDEL_CAN, 4 had N-score above 10. Of the remaining 40, for 24 loci (L1HS_1_47, 1_84c, 3_2, 3_5, 4_58c, 5_5c, 5_51c, 5_65c, 7_7c, 7_10, 8_27, 8_41, 8_42c, 8_43c, 10_24, 12_14, 12_27, 15_18, 18_5c, 18_8, 20_3, X_13, X_72 and X_114), the flanks were separated by less than 50 bases and probably represent insertion-mediated deletions. Of these, 3, (L1HS_7_7c, 8_41, 8_42c), were earlier reported by Han et al. L1HS_1_3 is a false positive. L1HS_1_69c is peculiar since the L1 insertion in chimpanzee is slightly smaller than the insertion in human suggesting parallel independent insertion post divergence of human and chimpanzee genomes. N-stretch at the beginning of the identified ortholog for L1HS_1_86c confounds its analysis. L1HS_9_31 represents an occupied locus, but is annotated as INDEL_CAN for lack of complete matches for the repeat overhangs. L1HS_2_55 and 3_53 insertions in the human genome result in deletion of 385 and 69 bases of non repeat sequence respectively. L1HS_11_41c actually represents a recombination event in the human genome (M_INTER_RMD) but is annotated as INDEL_CAN for lack of complete match for the 3' overhang. L1HS_10_43c has been earlier reported as confirmed L1 insertion-mediated deletion. The identified orthologs for L1HS_2_83, 3_108, 4_48, 16_25, 22_2c and Y_14c are repeat rich and could either represent sequences deleted upon L1 insertion in the human genome or parallel independent insertions. L1HS_4_74 has very low query coverage for the 5' flank and may be a false positive. L1HS_7_11 also has very low query coverage for the 5' flank and an N-score ~10 and therefore discarded.

14 orthologs were annotated as INDEL_PAC. Of these, 2 had N-score > 10 and were not considered further. Of the remaining 12, 8 (L1HS_2_18c, 3_48, 3_74, 4_37, 5_12, 7_45c, 12_38 and 18_18) had the flanks separated by not more than 50 bases and most likely represent insertion-mediated deletion. L1HS_11_62 and 16_1 (16_1 - also reported as insertion-mediated deletion earlier by Han et al.) have RISCI score of 100 and almost full query coverage and represent insertion-mediated deletions. L1HS_7_47 and 8_21c have low RISCI score and are doubtful.

28 loci were annotated as INDEL_PTS by RISCI. Of these, 15 had N-scores lower than or equal to 10. Most of the transduced sequence is repetitive in nature and could not be traced to the source locus.

Inferences based on comparisons with Celera and HuRef genome

In contrast to the chimpanzee genome, 1227 loci in the Celera and 1174 in the HuRef genome were annotated as OCCUPIED (Additional file 4). Among these, 1107 loci were commonly occupied in all 3 human genomes representing the more ancestral or fixed loci. Of these, 382 were inserted in genes.

8 C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD were reported in comparison with Celera genome. Of these, 4 have N-score below 10, 3 of which (L1HS 4_117c, 8_26 and 11_41c) are true inter-element recombination in the human genome. The recombining L1s were separated by 437 and 1216 bases in L1HS_8_26 and 11_41c respectively, and adjacent to each other in L1HS_4_117c. L1HS_2_42 represents a minor disruption of the parent repeat (C_DISRUPTED) in the Celera genome. Of the 13 C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED reported, 9 had N-score below 10. Of these, 12_41 is a confirmed inter-element recombination (C_INTER_RMD) in the Celera genome. L1HS_4_8, 4_9, 18_2c and 18_3c represent disruption in one of the two halves of a twin-primed L1 in the human genome (M_DISRUPTED). 11_30c is actually OCCUPIED but misannotated due to lack of match for the 3' repeat overhang. L1HS_3_14c, 4_23c and 7_15c are annotated as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED, but the region of homology where recombination may have taken place is not apparent. 3 C_INTRA_RMD events identified in Celera have varying length N-stretch and are possibly assembly errors. Of the 7 M_INTRA_RMD loci, only one had an N-score <10 (N-score = 0) and represents true M_INTRA_RMD event (Additional files 4, 5 and 6).

11 C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD were reported by RISCI in the HuRef assembly 5 of which had N-scores less than 10 (Additional files 1 and 2). Of these L1HS_2_41, 9_49c, 14_20 and 18_5c represent inter element recombination in the human genome. L1HS_11_57 is doubtful. 1 C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED are reported in HuRef assembly. Of these, 5 had N-score > 10. Of the remaining 16, 6 (L1HS_4_29, 5_80, 5_97, 18_12c, 20_16c and Y_19) had Ns at the 5' or the 3' end of the identified ortholog. These are most likely to be OCCUPIED loci but annotated so for lack of match to one of the repeat overhangs due to Ns. L1HS_11_30c is also OCCUPIED but misannotated. L1HS_1_63 represents inter element recombination in the HuRef genome. L1HS_2_49c, 2_50c, 4_8, 4_9, 13_34c, 18_2c and 18_3c represent disruptions in the main genome (M_DISRUPTED). L1HS_3_14, as mentioned earlier, is annotated as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED in all the three comparative genomes. However, the region of homology where recombination takes place is not apparent. 12 C_INTRA_RMDs were reported in HuRef. 7 had low N-scores. Of these, the orthologs for L1HS_10_25 and 13_20 have low N-scores and differ considerably from reference human insertion and may represent true intra element recombination in HuRef. Of the 36 reported M_INTRA_RMD events, only 6 had N-score less than 10. L1HS_2_51c, 5_93c and 8_5 represent true M_INTRA_RMD events. A longer length L1 was found at the orthologous locus in HuRef for each of these and the L1 sequence from the main genome matched perfectly either to the 5' or the 3' end of ortholog.

TSDs were identified for 90 elements in Celera and 112 in comparison with HuRef assembly. These represent recent and, therefore, polymorphic insertions in the human genome, amenable to phylogenetic studies. Of these, 62 in Celera and 76 in HuRef comparisons were canonical insertions in the reference human genome, 16 in Celera and 22 in HuRef had misannotated poly A tails (PAC) and 12 loci in Celera and 14 in HuRef were annotated as PTS (3' flank transduction). The source locus in the reference genome and comparative genomes was unambiguously identified for 6 (L1HS_10_28, 18_12c, 4_92, 5_74, 7_32 and X_113) loci in Celera and 5 (L1HS_4_92, 5_74, 6_12c, 7_32 and 4_83) in HuRef (Additional file 2). The PTS sequence for others was repeat-rich, preventing identification of the source locus.

9 INDELS were reported in comparison with the Celera genome. 5 had N-scores less than ten. Of the 3 loci annotated as INDEL_CAN or INDEL_PAC, L1HS_4_37 (annotated as INDEL_CAN in Chimpanzee and HuRef as well) and X_72 represent insertion mediated deletions. The ortholog identified for L1HS_5_93c has Ns at the beginning of the sequence confounding the analysis. Of the 6 loci annotated as INDEL_PTS, 2 had N-score < 10. L1HS_6_12c was found to true and the source locus for the PTS was also unambiguously identified. L1HS_12_42 may be false positive. 11 INDELS were reported in the HuRef assembly. Of these, 6 had N-score below 10. Three of the remaining 5 loci (L1HS_9_31, X_45c and Y_9) have Ns either in the beginning or end of the ortholog sequence. L1HS_4_37 represents insertion-mediated deletion. Y_30c is a false positive.

17 twin-priming events and 1 disruption were identified in Celera comparisons since most loci are nondifferential. 24 twin priming events and 1 disruption were identified in HuRef genome.

3. Analysis of AluYa5 retrotransposons

A total of 4056 (full length and truncated) AluYa5 elements were mined by RISCI in the reference human genome by using the RISCI_RM (direct parsing of repeat coordinates from pre-masked files) option. Using an arbitrary threshold of 285 bases, 3418 qualified as full length and 638 as truncated. 1594 of all Alus were inserted into genes in the reference human genome (5' UTR or intronic). Unless otherwise stated, the inferences refer to the transposon locus in the reference (reference human) genome (Table 1, Additional files 7, 8, 9 and 10).

Inferences based on the orthologous locus in the reference chimpanzee genome

a) Shared ancestry

314 loci were found to be occupied at the orthologous loci in chimpanzee.

b) Post insertion changes

5 loci were annotated as C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD. Of these, 2 (Alu_1_38 and X_18c) had N-scores > 10 and were not considered further. Of the remaining 3, 2 (Alu_6_210 and 16_96c) were confirmed as M_INTER_RMD, while Alu_17_2 represents a truncated insertion in human and full length insertion in chimpanzee. A recombination between Alu monomers may be responsible for this situation. 90 C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED events were identified in chimpanzee. Of these, 72 were found to be true inter-element recombination (C_INTER_RMD) events in chimpanzee (Additinal files 3, 4). Another 8 (AluYa5_5_145c, 6_27c, 6_226c, 11_160c, 17_5, 20_69, 22_19, 22_31 were found to be OCCUPIED but were annotated so for lack of almost perfect match for the repeat overhangs. AluYa5_2_250 has Ns at the beginning of the identified ortholog and hence misannotated. It too is likely to be occupied. The remaining 7 (7_95c, 15_89, 17_100, 17_105, 19_57, 20_26, 7_95) are doubtful. As expected, no C_INTRA_RMD event was identified. M_INTRA_RMD option was inactivated for this run.

Inferences based on empty allele at the orthologous locus

TSDs were identified for 3209 loci, of which 3132 loci were annotated as CAN, 54 as PAC and 23 as PTS. However, all 23 predicted transduced sequences were either repeat rich or were too small to facilitate identification of source locus (Additional file 5).

Insertion-mediated deletion or parallel independent insertions or insertion-deletions

267 loci (164 INDEL_CAN, 7 INDEL_PAC and 96 INDEL_PTS) were annotated as INDELS. Of the 171 INDEL_CAN or INDEL_PAC, 132 had N-score less than 10. At least 60 of these (marked in blue) appear to be insertion-mediated deletions. Another 13 are recombination-mediated deletions, misannotated as INDEL_CAN for lack of match for the repeat overhang (marked in red or brown) (Additional files 7, 8 and 9). Of the 96 loci annotated as INDEL_PTS, 34 had N-score less than 10. As mentioned earlier, we advise user discretion while dealing with INDEL_PTS. Most of these may result from RISCI trudging into loci that are not truly orthologous for lack of sequence (substituted by Ns) at the actual orthologous locus.

Inferences based on comparisons with Celera and HuRef genomes

In contrast to the chimpanzee genome, 3530 and 3335 loci were found to be OCCUPIED in Celera and HuRef genomes respectively (Additional file 7).

9 loci in Celera and 6 in HuRef were annotated as C_DISRUPTED_M_INTER_RMD. All 8 orthologous loci in Celera (N-score < 10) and 4 in HuRef (N-score < 10) had homologous Alu sequences at the 5' and the 3' end, confirming inter-element recombination in the human genome. 22 in Celera and 74 in HuRef were annotated as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED. Of these, 13 in Celera had N-score < 10. Of these, 2 (AluYa5_3_94c and 18_41c) had Ns at the beginning or end of the identified ortholog. Of the remaining 11, 7 were confirmed as C_INTER_RMD. Other 3, AluYa5_2_181, 6_204 and 22_19, were found to be occupied. AluYa5_5_222c is doubtful. Of the 74 loci in HuRef, 46 had N-scores <10. Of these 46, 29 had Ns at the beginning or end of the identified ortholog sequence and are likely to be occupied in HuRef. AluYa5_2_67c, 8_19, 9_172c, 16_26, 16_67, 17_48 and 19_28 are true inter Alu recombinations in the HuRef genome. The orthologous locus identified for AluYa5_16_26, 16_28c, 16_37 and 16_38 was the same. 6 loci were found to be OCCUPIED but missannotaed as C_INTER_RMD_M_DISRUPTED for lack of match for one of the repeat overhangs.

330 (326 CAN, 2 PAC and 2 PTS) loci in Celera and 428 (420 CAN, 4 PAC and 4 PTS) in HuRef were found to be empty. 59 INDELS (34 INDEL_CAN, 1 INDEL_PAC and 24 INDEL_PTS) were reported in Celera genome. 19 of these had N-scores less than 10. Of these, 4 (AluYa5 3_54, 4_120c, 11_26 and X_7) had Ns at either the beginning or the end of the identified ortholog confounding the analysis. AluYa5 2_322c (10 bp), 4_245 (913 bp), 8_149 (3 bp), 15_74 (25 bp) and X_75 (1966 bp), represent insertion-mediated deletions. The orthologs for Alu_4_194c and 14_98c have full length Alu sequence at the 5' end followed by non Alu sequence suggesting gene conversion, while 6_52 represents parallel insertion of LTR sequence Alu_2_59 possibly results from recombination between Alu monomers. 132 (79 INDEL_CAN and 53 INDEL_PTS) in HuRef were reported. 33 of these had N-score less than 10. Of these, AluYa5_2_59, 2_322c, 4_194c, 4_245, 6_52, 8_149, 14_98c and 15_74 are exactly similar to Celera orthologs as described above. Another 7 (AluYa5_1_313, 5_10, 10_109c, 13_23, 14_100, 20_71c and X_4) had Ns either in the beginning or end of the ortholog sequence leading to misannotation.

Novel polymorphism

A total of 45 polymorphic sites were identified in comparison with the Celera and HuRef assemblies. Of these 32 were common to both Celera and HuRef, while for others the orthologous locus was empty either in Celera or HuRef assembly. To ascertain how many of the 45 polymorphisms were novel, we cross checked with the L1 insertion polymorphism data in dbRIP by using its recently incorporated 'Position mapping' utility [71]. Of the 45 polymorphic sites reported, 14 did not find a match in the dbRIP recently updated data and are novel (Table 3, Additional files 11 and 12). Of these, 9 had RISCI score of 100 (unique ortholog identified). Likewise, for truncated L1HS, of the 113 empty orthologous loci either in Celera or HuRef or in both, 47 were not found in dbRIP. 24 of these had RISCI score of 100. Of the 435 AluYa5 loci for which an empty ortholog was identified in Celera or HuRef genomes or in both, 140 are not mentioned in dbRIP. All of these had RISCI score of 100 suggesting unambiguity in identifying the ortholog (Additional file 12). The polymorphic sites essentially represent insertions in the reference human genome but absent in Celera or HuRef or in both.

Table 3.

Novel polymorphic loci predicted by RISCI for full length L1HS by comparison of reference human genome with the alternate human genomes

| LOCUS | Ortholog empty in | R-score | hg18 coordinates | Match in dbRIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1HS_1_4c | HuRef | 80 | chr1:81177500-81183677 | NA |

| L1HS_1_5c | Celera, HuRef | 100 | chr1:84290051-84296742 | NA |

| L1HS_4_3c | Celera, HuRef | 100 | chr4:18688621-18694707 | NA |

| L1HS_4_13c | Celera, HuRef | 56.5 | chr4:75861787-75867832 | NA |

| L1HS_5_24 | HuRef | 100 | chr5:177131852-177137889 | NA |

| L1HS_7_10c | Celera, HuRef | 100 | chr7:96313896-96319990 | NA |

| L1HS_9_2c | Celera, HuRef | 100 | chr9:46329639-46335695 | NA |

| L1HS_11_4c | Celera, HuRef | 57 | chr11:48825824-48831881 | NA |

| L1HS_11_12 | Celera, HuRef | 99 | chr11:92793798-92799846 | NA |

| L1HS_14_1c | Celera, HuRef | 88 | chr14:18130292-18136344 | NA |

| L1HS_X_9c | HuRef | 100 | chrX:65317263-65323363 | NA |

| L1HS_Y_1 | Celera | 100 | chrY:3371591-3378526 | NA |

| L1HS_Y_2c | Celera | 100 | chrY:4876952-4882987 | NA |

| L1HS_Y_3c | Celera | 100 | chrY:5534205-5540267 | NA |

Details for these loci may be referred to in Additional file 1.

Discussion

Salient features of RISCI

RISCI offers both whole genome as well specific region analyses. It runs on contig as well as on assembled chromosome sequence, allows multiple genome comparisons, offers three repeat mining utilities (RISCI_RM, RISCI_NON_RM and RISCI_BLAST, and two filters 'length' and 'gene' (see materials and methods). Wherever possible, the upstream query sequence is tagged with a user defined length of non repeat sequence (default- 500 bp) to avoid spurious hits (see materials and methods). In most cases this non repeat tag forms a part of the upstream blast hit used in RISCI annotation (Additional File 17 Figure S4). RISCI also uses improvised soft masking (see materials and methods) to arrive at the orthologous locus in the comparative genome. The blast databases of the genomes are made with the - o option set to T to enable use of fastacmd so as to speedily retrieve flank sequence from the reference genome and the ortholog sequence from the comparative genome. A merger option is also provided so as to merge BLAST hits in the comparative genome if the gap between two similarly oriented Blast HSPs is not greater than the user defined length (default 50 bp) both in terms of the query and subject coordinates. A scoring scheme has also been implemented to assign confidence scores in cases where multiple orthologous loci are predicted (see materials and methods). As mentioned above, specialized modules to take care of complications involved in truncated repeat analysis are inbuilt. Confirmation module for flank transduction is also inbuilt in RISCI. Besides, 3 speed options are inbuilt (Table 4).

Table 4.

Details of Speed options in RISCI

| Parameters | Fast | Medium | Slow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blast -v | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Maximum no of Blast HSPs compared | 100 (in each orientation) | 500 (in each orientation) | 10000 (in each orientation) |

| Pros and cons | fastest, least accurate | Fast, reasonably accurate | Most accurate |

For each of the speed options (Fast, Medium and Slow), speed may be further enhanced by selecting for "STOP AT FIRST MATCH (SFM)" as opposed to "ALL AGAINST ALL COMPARISONS". SFM option stops further comparisons as soon as the first match conforming to any of the RISCI alignment signatures is found. To avoid orientation bias, the control shifts between plus and minus hits every 15 hits. The scoring scheme becomes redundant since only one match is allowed, and hence duplications cannot be identified with SFM option.

Medium speed option with SFM off and merger on is recommended.

Comparison with other tools