Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and type 2 diabetes have independent adverse effects on sexual functioning (SF). Bupropion (BU) reportedly has few sexual side effects, but its use in diabetes has not been studied.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This article reports a planned secondary analysis of SF in 90 patients with type 2 diabetes treated with BU for MDD.

RESULTS

At baseline, 71.1% of patients had insufficient SF. Mean Sexual Energy Scale (SES) scores improved during treatment (P < 0.0001), as did the percentage with sufficient SF (30.6 vs. 68.1%, P = 0.001). Patients with persistent hyperglycemia had higher rates of sexual dysfunction; however, SES improvement was evident in some with persistent depression or hyperglycemia (18.2% and 25.9%, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS

Insufficient SF is prevalent and may be suspected in patients with MDD and type 2 diabetes. BU treatment of MDD had few sexual side effects and was associated with significant improvements in SF.

The adverse effects of diabetes on sexual functioning (SF) are well established. Depression and the medication used to treat it may impose additional risk of sexual dysfunction in patients with diabetes (1,2). Bupropion (BU) has gained favor in major depressive disorder (MDD) treatment, in part because of its lower potential for sexual dysfunction. This article reports a planned secondary analysis of SF data from a clinical trial of BU for MDD in patients with type 2 diabetes (3). The aims of this analysis were to determine the 1) prevalence of sexual dysfunction, 2) occurrence of sexual side effects with BU treatment, and 3) SF changes that occur during BU therapy.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This article reports on 18- to 80-year-old patients with symptomatic major depression disorder (MDD) defined by conventional criteria (4) and type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with extended-release BU in an open-label fashion over a 10-week study period (3). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and all subjects provided informed consent.

Measures

Demographic, anthropometric, medical, and diabetes history data were collected on participants at enrollment. Glycemic control was measured with A1C. Current depression severity was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (5). MDD remission was defined as a BDI score of ≤9 after BU treatment. The Sexual Energy Scale (SES) was used to provide an ordinal assessment of SF (1–10 scale; 1 = “lowest sexual energy,” 10 = “highest prior sexual experiences”). SES scores of ≥5 were regarded as satisfactory SF, and scores <5 denoted the presence of sexual dysfunction (6).

Statistical analyses

Independent sample t tests were performed to assess between-group differences in continuous variables. χ2 and Fisher exact tests were performed to determine between-group differences of categoric variables. Sexual dysfunction and hyperglycemia evident at both pre- and posttreatment are referred to as “persistent sexual dysfunction” and “persistent hyperglycemia,” respectively.

RESULTS

Ninety subjects (mean age 51.4 years, 63.3% were female, 46.7% were Caucasian) were initiated on BU therapy. Eighteen subjects (19.3%) failed to complete the study. Baseline rates of sexual dysfunction were similar between protocol completers and noncompleters (P = 0.48). Of the 72 participants who completed treatment, 61 (84.7%) met criteria for MDD remission. Sexual dysfunction was evident at baseline in 64 (71.1%) of the 90 study participants. Of these, 50 completed BU therapy and 28 (56%) experienced improved SF.

At baseline, participants with sexual dysfunction were older (52.8 vs. 48.0 years, P = 0.04) and had longer duration of MDD (25.5 vs. 18.3 years, P = 0.03). There were no significant between-group differences in depression or A1C. A trend toward longer duration of type 2 diabetes existed in those with sexual dysfunction (7.8 vs. 5.6 years, P = 0.14).

Those with persistent sexual dysfunction after therapy were older (55.1 vs. 52.0 years, P = 0.11) and had higher A1C (8.5 vs. 7.1%, P = 0.02). In contrast with baseline measures, significantly higher BDI scores after therapy were observed in those with persistent sexual dysfunction (9.0 vs. 4.9, P = 0.007).

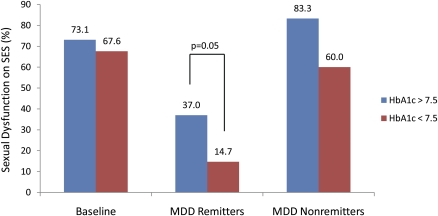

SES improved significantly during treatment (SES mean pre- and posttreatment: 3.4–5.6, P < 0.0001), with 51 (70.8%) free of sexual dysfunction per established SES thresholds. This represented a significant improvement in rates of satisfactory SF (50/72, 69.4% vs. 23/72, 31.9%; χ2 = 10.9, P = 0.001). Although improvement in SF was greatest in those with gains in depression and glycemic measures, it was also observed in two of 11 subjects (18.2%) who did not achieve depression remission and in seven of 27 subjects (25.9%) who had persistently elevated A1C levels (Fig. 1). Nominal improvements in SES after BU therapy (mean SES change of 0.6 ± 1.3) were experienced by those without improvement in SF. By comparison, those who had improved SF had a sevenfold change in SES (4.3 ± 1.7, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Rates of sexual dysfunction (broken down by mean A1C) at baseline and in those with depression remission to BU. At baseline, no differences in sexual dysfunction were seen based on A1C after therapy; however, those with higher A1C levels had greater rates of sexual dysfunction, irrespective of depression remission to BU therapy. Whereas improvement in sexual functioning was greatest in those who experienced MDD remission and lower A1C levels, it was also observed in some subjects who did not achieve remission or who had persistently elevated A1C levels. Sexual dysfunction was determined using an SES score <5.

CONCLUSIONS

We found a high rate (71.1%) of sexual dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes and MDD despite a modest rate of neuropathy (22.2%). SF improved significantly during BU therapy of MDD, with 58% of subjects experiencing substantial gains in SF during this interval. This effect was more robust in those with greater improvements in depression and glycemic control, but was still observed in approximately 20% of those with persistent MDD or hyperglycemia.

Diabetes may negatively influence SF though multiple pathophysiologic pathways, that is, vascular, neurologic, and hormonal effects (7–10). Hyperglycemia also impairs SF and may have been a factor in this sample (mean A1C >8%) (11). MDD imposes additional risk of hyperglycemia (12), and indeed, A1C and BDI scores were positively correlated both at baseline and after BU therapy. Although depression, A1C, and SF tended to improve in concert, SF also improved significantly in 25% of those with persistent hyperglycemia.

In persons without diabetes, the risk of treatment-related sexual dysfunction is four to six times higher with selective serotonin- and norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors compared with BU (13), possibly because of BU’s lack of influence on serotonergic presynaptic reuptake. Our findings add to evidence suggesting low sexual side effects with BU; indeed, new onset of sexual dysfunction occurred in only one subject. BU augmentation of dopamine effects regarded as important to arousal and orgasm may account for observed improvements in SF (14).

In summary, this study is the first to report on the high rate of sexual dysfunction in persons with diabetes and depression. Significant improvements in mood, glycemic control, and SF were observed during BU treatment of MDD. However, improvement in SF was still seen in approximately 20% of those with persistent depression or hyperglycemia. Limitations of the study relate to its small sample size, short-term treatment period, open treatment design, and use of a global measure of SF, the latter precluding comment on the specific nature of experienced sexual difficulties or improvements. Our findings support the need for routine assessment of SF in patients with type 2 diabetes and MDD, and affirm the importance of mood and glycemic control in SF. Selection of antidepressants with lower sexual side effects, such as BU, should yield the greatest potential for sexual and mental well-being in patients with type 2 diabetes and depression.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

G.S.S. researched data, contributed to discussion, wrote the article, and reviewed and edited the article. B.M.G. researched data, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the article. B.D.N. researched data. P.J.L. contributed to discussion, wrote the article, and reviewed and edited the article.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Montejo-González AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J Sex Marital Ther 1997;23:176–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane RM. A critical review of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-related sexual dysfunction; incidence, possible aetiology and implications for management. J Psychopharmacol 1997;11:72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lustman PJ, Williams MM, Sayuk GS, Nix BD, Clouse RE. Factors influencing glycemic control in type 2 diabetes during acute- and maintenance-phase treatment of major depressive disorder with bupropion. Diabetes Care 2007;30:459–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., Text Revision Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Association, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry 1974;7:151–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnock JK, Bundren JC, Morris DW. Female hypoactive sexual desire disorder due to androgen deficiency: clinical and psychometric issues. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33:761–766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morano S. Pathophysiology of diabetic sexual dysfunction. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26(Suppl):65–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCulloch DK, Young RJ, Prescott RJ, Campbell IW, Clarke BF. The natural history of impotence in diabetic men. Diabetologia 1984;26:437–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser FE, Korenman SG. Impotence in diabetic men. Am J Med 1988;85(5A):147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim NN. Sex steroid hormones in diabetes-induced sexual dysfunction: focus on the female gender. J Sex Med 2009;6(Suppl. 3):239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romeo JH, Seftel AD, Madhun ZT, Aron DC. Sexual function in men with diabetes type 2: association with glycemic control. J Urol 2000;163:788–791 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM. Depression and poor glycemic control: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 2000;23:934–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F, Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl. 3):10–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]