Abstract

A 9-year-old girl presented with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. Esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy (EGD) identified a long and large gastric trichobezoar extending into the duodenum. We attempted endoscopic retrieval after informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother. Initially, a gasper with 5-prolongs, commonly used for retrieval of endoscopically excised polyps, failed to remove the whole trichobezoar. When a net was used instead, it proved impossible to remove the trichobezoar completely. Therefore, we withdrew the scope from the mouth, leaving the net grasping the tricobezoar firmly in the stomach. Subsequently, we were able to retrieve about 70% of the trichobezoar manually by grasping the snare part of the net directly. A second pass found no deep laceration or perforation endoscopically. The remaining trichobezoar was completely retrieved with the net. The procedure was completed within 15 min. The retrieved specimens were 34 cm in length and 100 g in weight. The patient was discharged uneventfully 5 d thereafter. She was advised to visit a psychiatrist to avoid suffering from a relapse. Follow-up EGD showed no trichobezoar, and the patient’s frontal hair grew back.

Keywords: Gastric bezoar, Trichobezoar, Endoscopic retrieval, Grasper, Retrieval net

INTRODUCTION

Bezoars are collections of indigestible materials that accumulate to form a mass in the gastrointestinal tract. Most are commonly found in the stomach, and they can be categorized into five major groups: (1) phytobezoars; (2) pharmacobezoars; (3) trichobezoars; (4) lactobezoars; and (5) foreign body bezoars, according to their composition. Trichobezoars, composed of hair, usually occur in young women and cases which extend throughout the small bowel into the cecum, are known as the Rapunzel syndrome[1]. Gastric trichobezoars are generally more difficult to remove endoscopically and, thus, most reported cases require surgery[2]. Herein we report a case of a gastric trichobezoar successfully retrieved with endoscopy.

CASE REPORT

A 9-year-old girl presented with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. She had experienced bullying at her elementary school for two years. Over the same period, her mother noticed her habit of trichotillomania (hair pulling) and trichophagia (hair eating). The girl was unconscious of this habit but had tried to vomit the eaten hair when it was noticed or she was warned. She had no prior history of medical problems or mental disturbance. At first, she visited a nearby hospital because of abdominal pain. Physical examination showed a healthy 9-year-old girl with a body weight of 33 Kg and a height of 1.33 m. There was frontal balding and mild tenderness without defense or rigidity in the epigastric region, although no abdominal mass was palpable. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed an inhomogenous mass in the stomach. Therefore, she was sent to our hospital for further investigation and treatment. Laboratory data were within normal limits except for a slight elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP; 1.3 g/dL).

Endoscopic technique

A transnasal esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy (EGD) identified a long and large gastric trichobezoar extending into the duodenum (Figure 1). We attempted endoscopic retrieval after informed consent had been obtained from the patient’s mother. A standard gastroscope (GIFQ260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used after intravenous administration of midazolam (7 mg). To avoid bowel movement and to relax the lower esophageal sphincter, scopolamine butylbromide (20 mg) was administered intravenously before endoscopic removal. Carbon dioxide (CO2) was administered using a CO2 regulator (Olympus UCR; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) connected to the endoscope supply tube for insufflation during the endoscopic procedure.

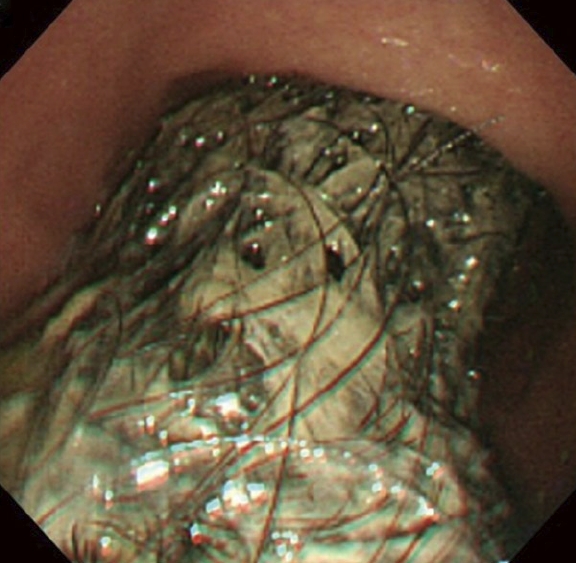

Figure 1.

A transnasal esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy identified a long and large gastric trichobezoar extending into the duodenum.

Initially, we used a gasper with 5-prolongs, commonly used for retrieval of endoscopically excised polyps, (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). However we could only remove completely the portion of the trichobezoar present in the stomach as passage of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) was impossible (Figure 2). We then attemted retrieval using a net, also commonly used for retrieval of excised colorectal polyps (Figure 3). The trichobezoar did pass EGJ in part but we could not retrieve the whole of it with the endoscope. Therefore, we withdrew the scope from the mouth leaving the net grasping the trichobezoar firmly in the stomach. Subsequently, we were able to retrieve about 70% of the trichobezoar manually by grasping the snare part of the net directly. A second pass found mild erosion at the EGJ, although no deep laceration or perforation was detected endoscopically. The remaining trichobezoar was completely retrieved with the net. The whole procedure was electronically recorded and was completed within 15 min. The retrieved specimens were 1.8 cm × 3.2 cm × 34 cm in length and 100 g in weight (Figure 4). The patient was discharged uneventfully 5 d after endoscopic retrieval. She was advised to visit a psychiatrist to avoid suffering from a relapse. Follow-up EGD showed no trichobezoar, and her frontal hair grew back.

Figure 2.

A standard gastroscope (GIFQ260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for retrieval. A gasper with 5-prolongs (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), commonly used for retrieval of polyps excised endoscopically, was used to retrieve the gastric trichobezoar.

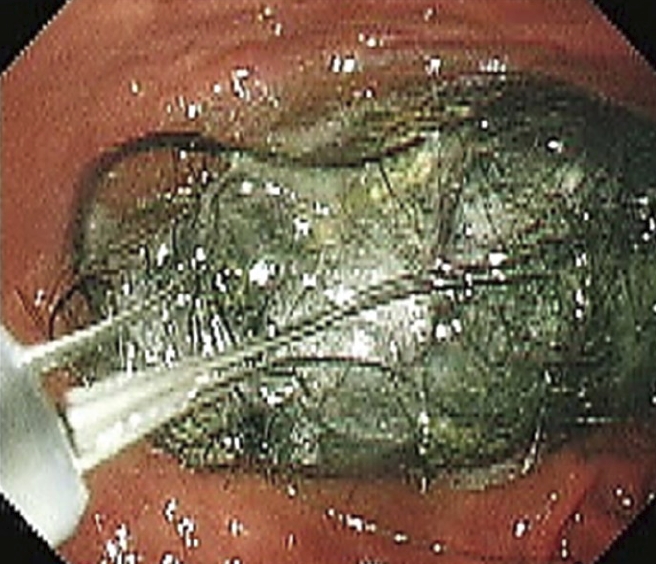

Figure 3.

A net for collecting the removed colorectal polyps was used instead of a grasper for endoscopic retrieval.

Figure 4.

The retrieved specimens were 1.8 cm × 3.2 cm × 34 cm in length and 100 g in weight.

DISCUSSION

Endoscopic retrieval or surgical removal are chosen for bezoar removal based on the size and composition. As gastric trichobezoars are generally more difficult to remove endoscopically, most of the reported cases required surgery[2]. Laparoscopic removal is cosmetically superior to open laparotomy[3,4]. However, if possible, endoscopic removal is less invasive and can save time, cost and abdominal damage. To the best of our knowledge, however, there are only two successful cases reported in the English literature[5,6]. Soehendra used a Nd: YAG laser to disrupt the bezoar followed by the retrieval of its fragments, requiring more than 100 passages of the endoscope in three sessions of 2 to 3 h[5]. This procedure is, therefore, troublesome and needs special equipment. Meanwhile, Saeed carried out successful retrieval using a two-channel endoscope, an overtube, and a grasping forceps with the patient under intubation[6].

In our case, we used a single channel endoscope, a grasper, and a net to remove the trichobezoar completely in one session (two passages of endoscope) with the patient under sedation and without intubation. We conducted the endoscopic procedure under sedation instead of general anesthesia after discussion with the anesthetists and pediatric surgeons in our hospital. We would have performed the procedure under general anesthesia if we could not have completed the endoscopic retrieval safely within 30 min. The shape of the trichobezoar in our case was most important for successful endoscopic retrieval. If the maximal diameter had been too large to pass the esophagogastric junction, we would not have been able to retrieve it endoscopically. Considering the whole procedure retrospectively, the grasping power of a grasper with 5-prolongs was not as great as that of a net, although the trichobezoar could not be removed with the endoscope even used together with a net. If we had used a two channel endoscope backloaded with an overtube according to Saeed’s suggestion, the bezoar would have been grasped more firmly, enabling the passage of the EGJ more easily. However, holding the snare part of the net directly following withdrawing the endoscope from the mouth, eventually enabled us to retrieve the grasped trichobezoar successfully. Furthermore, we used CO2 insufflation to avoid esophageal perforation associated with laceration caused by endoscopic retrieval.

In conclusion, we have reported a case of a gastric trichobezoar successfully retrieved endoscopically using a net made for polyp retrieval. Endoscopic removal of a gastric trichobezoar is less invasive and cost effective than surgical removal and this procedure should, therefore, be considered as an option for treatment with various endoscopic accessories.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Takayuki Yamamoto, MD, PhD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Yokkaichi Social Insurance Hospital, 10-8, Hazuyamacho, Yokkaichi 510-0016, Japan; Philip Wai Yan Chiu, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Institute of Digestive Disease, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, 30-32 Ngan Shing Street, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Liu N

References

- 1.Vaughan ED Jr, Sawyers JL, Scott HW Jr. The Rapunzel syndrome. An unusual complication of intestinal bezoar. Surgery. 1968;63:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Backer A, Van Nooten V, Vandenplas Y. Huge gastric trichobezoar in a 10-year-old girl: case report with emphasis on endoscopy in diagnosis and therapy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:513–515. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199905000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nirasawa Y, Mori T, Ito Y, Tanaka H, Seki N, Atomi Y. Laparoscopic removal of a large gastric trichobezoar. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:663–665. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanetaka K, Azuma T, Ito S, Matsuo S, Yamaguchi S, Shirono K, Kanematsu T. Two-channel method for retrieval of gastric trichobezoar: report of a case. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:e7. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soehendra N. Endoscopic removal of a trichobezoar. Endoscopy. 1989;21:201. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS, Dixon WB. A method for the endoscopic retrieval of trichobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:698–700. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]