Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the effects of krill oil and fish oil on serum lipids and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation and to evaluate if different molecular forms, triacylglycerol and phospholipids, of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) influence the plasma level of EPA and DHA differently. One hundred thirteen subjects with normal or slightly elevated total blood cholesterol and/or triglyceride levels were randomized into three groups and given either six capsules of krill oil (N = 36; 3.0 g/day, EPA + DHA = 543 mg) or three capsules of fish oil (N = 40; 1.8 g/day, EPA + DHA = 864 mg) daily for 7 weeks. A third group did not receive any supplementation and served as controls (N = 37). A significant increase in plasma EPA, DHA, and DPA was observed in the subjects supplemented with n-3 PUFAs as compared with the controls, but there were no significant differences in the changes in any of the n-3 PUFAs between the fish oil and the krill oil groups. No statistically significant differences in changes in any of the serum lipids or the markers of oxidative stress and inflammation between the study groups were observed. Krill oil and fish oil thus represent comparable dietary sources of n-3 PUFAs, even if the EPA + DHA dose in the krill oil was 62.8% of that in the fish oil.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3490-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plasma lipoproteins; Plasma lipids; Dietary fat; Nutrition, n-3 fatty acids; Lipid absorption; Phospholipids

Introduction

An association between consumption of fish and seafood and beneficial effects on a variety of health outcomes has been reported in epidemiologic studies and clinical trials [1–5]. These effects are mainly attributed to the omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) abundant in fish and seafood, and in particular to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The effects of marine n-3 PUFAs on various risk factors of cardiovascular disease (CVD) are in particular well documented. In large systematic reviews of the available literature, consistent reductions in triglyceride (TG) levels following consumption of n-3 PUFAs have been demonstrated as well as increases in levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [6, 7]. The net beneficial effects of these changes have been disputed, although several large intervention studies indicate that n-3 PUFAs reduce mortality in patients with high risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) [8]. Moreover, guidelines published by the American Heart Association for reducing CVD risk recommend fish consumption and fish oil supplementation based on the acknowledgement that EPA and DHA may decrease the risk of CHD, decrease sudden deaths, decrease arrhythmias, and slightly lower blood pressure [9].

Reports on health benefits have led to increased demand for products containing marine n-3 PUFAs. Since fish is a restricted resource, there is growing interest in exploiting alternative sources of marine n-3 PUFAs. Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) is a rich source of n-3 PUFAs. Krill is by far the most dominant member of the Antarctic zooplankton community in terms of biomass, which is estimated to be between 125 and 750 million metric tons (according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3393/en), and thus attractive for commercial harvest. The DHA content of krill oil is similar to that of oily fish, but the EPA content is higher [10]. The overall fatty acid composition resembles that of fish. In fish, the fatty acids are mainly stored as TG, whereas in krill 30–65% of the fatty acids are incorporated into phospholipids (PL) [10]. Whether being esterified in TG or in PL impacts on the absorption efficiency of FAs into the blood and on effects on serum lipid levels are issues for discussion. In a study by Maki et al. [11] comparing the absorption efficacy of n-3 PUFAs from different sources it was shown that EPA and DHA from krill oil were absorbed at least as efficiently as EPA and DHA from menhaden oil (TG) [11], and studies in newborn infants have indicated that fatty acids in dietary PL may be better absorbed than those from TG [12–14]. Studies addressing the compartmental metabolism of dietary DHA have indicated that the metabolic fate of DHA differs substantially when ingested as TG compared with phosphatidylcholine, in terms of both bioavailability of DHA in plasma and accumulation in target tissues [15]. Only a limited number of studies addressing health outcomes following ingestion of krill oil as compared with fish oil are currently available, but some of these have shown promising effects of krill oil on serum lipids and on markers of inflammation and oxidative stress (reviewed in [10]).

The aim of this study is to investigate the plasma levels of EPA and DHA, and the effects on serum lipids and on some biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and hemostasis, after krill oil and fish oil administration in healthy subjects after a 7-week intervention period. Safety was evaluated based on assessment of hematology and biochemistry parameters, and registration of adverse events.

Experimental Procedures

Study Subjects

The 129 subjects included in the study were healthy volunteers of both genders with normal or slightly elevated total blood cholesterol (<7.5 mmol/L) and normal or slightly elevated blood triglyceride level (<4.0 mmol/L). Subjects with body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary, peripheral or cerebral vascular disease were excluded from participating in the study. No concomitant medication intended to influence serum lipid level was permitted. All study subjects were informed verbally and in writing, and all subjects signed an informed consent form before entering the study. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee.

Study Design

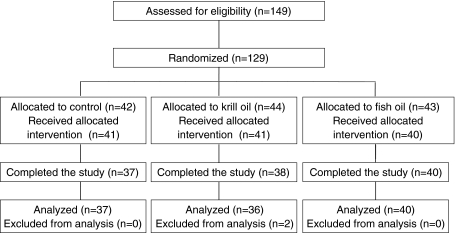

The study was an open single-center, randomized, parallel group designed study. Screening of subjects (N = 149) was performed at the first visit to include subjects that satisfied the eligibility criteria (N = 129). These were randomized into three study groups. Seven participants were lost before the baseline visit. The remaining 122 participants were given either 3 g krill oil daily (N = 41), 1.8 g fish oil daily (N = 40) or no supplementation (N = 41) for a period of 7 weeks. A total of 115 participants finished the study. The disposition of the subjects is illustrated in Fig. 1. None of the subjects regularly ate fatty fish more than once a week prior to inclusion or during the 7-week intervention period. None were using cod liver oil or other marine n-3 supplements during the study or at least 2 months prior to inclusion. All the participants were instructed by a nutritionist to keep their regular food habits during the study.

Fig. 1.

Disposition of subjects

Study Products

The krill oil capsules contained processed krill oil extracted from Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). The product was manufactured by Aker BioMarine ASA. Each capsule contained 500 mg oil that provided 90.5 mg EPA and DHA, and a total of 103.5 mg n-3 PUFAs. The capsules were made of gelatin softened with glycerol. The daily study dosage was six capsules (each of 500 mg oil). The comparator omega-3 fish oil product was manufactured by Peter Möller AS, Oslo, Norway. The daily study dosage was three capsules each containing 600 mg fish oil that provided 288 mg EPA and DHA, and a total of 330 mg n-3 PUFAs. The capsules were made of gelatin softened with glycerol. The fatty acid profile of the study products is presented in Table 1. The daily dose of EPA, DHA, and total n-3 PUFAs in the krill oil and fish oil groups is presented in Table 2. The daily EPA + DHA dose in the krill oil group was 62.8% of the dosage given in the fish oil group. dl-α-tocopheryl acetate (vitamin E), retinyl palmitate (vitamin A), and cholecalciferol (vitamin D) were added to the product.

Table 1.

Relative content of fatty acids in the study products

| Fatty acid | Fish oil (area %) | Krill oil (area %) |

|---|---|---|

| 14:0 | 3.2 | 7.4 |

| 16:0 | 7.8 | 21.8 |

| 18:0 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| 20:0 | 0.6 | <0.1 |

| 22:0 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| 16:1n-7 | 3.9 | 5.4 |

| 18:1n-9, -7, -5 | 6.1 | 18.3 |

| 20:1n-9, -7 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| 22:1n-11, -9, -7 | 2.5 | 0.8 |

| 24:1n-9 | <0.2 | 0.2 |

| 16:2n-4 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| 18:2n-6 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| 18:3n-6 | <0.2 | 0.2 |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.3 | <0.1 |

| 20:3n-6 | 0.2 | <0.1 |

| 20:4n-6 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| 22:4n-6 | 0.5 | <0.1 |

| 18:3n-3 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| 18:4n-3 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| 20:3n-3 | <0.2 | <0.1 |

| 20:4n-3 | <0.2 | 0.7 |

| 20:5n-3 | 27.0 | 19.0 |

| 21:5n-3 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| 22:5n-3 | 4.8 | 0.5 |

| 22:6n-3 | 24.0 | 10.9 |

| Other FA | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| Saturated FA | 16.0 | 30.7 |

| Monounsaturated FA | 18.0 | 25.9 |

| n-3 | 59.0 | 34.1 |

| n-6 | 2.9 | 2.5 |

Table 2.

n-3 fatty acid contents of the study products

| Study product | Daily study dose | Daily dose EPA | Daily dose DHA | Daily dose EPA + DHA | Daily dose n-3 PUFAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil | 3 capsules (1.8 g oil) | 450 mg | 414 mg | 864 mg | 990 mg |

| Krill oil | 6 capsules (3.0 g oil) | 348 mg | 195 mg | 543 mg | 621 mg |

Clinical Assessment

Demographic characteristics (gender, age, height, and weight), concomitant medication, and medical history were recorded at the screening visit. In addition, all subjects went through a physical examination to confirm satisfaction of the eligibility criteria.

Changes in concomitant medication from screening, smoking and alcohol habits, and clinical symptoms before intake of the study products were also registered.

Serum Lipids and Blood Safety Parameters

Blood from venipuncture was collected after an overnight fast (≥12 h) at baseline and at final visit. The subjects were instructed to refrain from alcohol consumption and from vigorous physical activity the day before the blood sampling. Serum was obtained from silica gel tubes (BD Vacutainer), kept at room temperature for at least 30 min until centrifugation at 1,300 × g for 12 min at room temperature. Serum analysis of total, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and HDL-cholesterol, TG, apolipoprotein A1, and apolipoprotein B was performed at the routine laboratory at Department of Medical Biochemistry at the National Hospital, Norway using standard methods. Blood samples for analysis of hematology and serum biochemistry parameters including hemoglobin, leukocytes, erythrocytes, thrombocytes, hematocrit, glucose, calcium, sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, albumin, and total protein were collected and analyzed at the routine laboratory at Department of Medical Biochemistry at the National Hospital, Norway using standard methods.

Plasma Fatty Acid Composition

Plasma was obtained from ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes (BD Vacutainer) kept on ice immediately and within 12 min centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 10 min at 10°C. Plasma samples were kept frozen at −80°C until analysis. Plasma fatty acid composition was analyzed by Jurilab Ltd., Finland using a slight modification of the method of Nyyssonen et al. [16]. Plasma (250 μL), fatty acids, and 25 μL internal standard (eicosane 1 mg/mL in isopropanol) were extracted with 6 mL methanol–chloroform (1:2), and 1.5 mL water was added. The two phases were separated by centrifugation, and the upper phase was discarded. To the chloroform phase, 1 mL methanol–water (1:1) was added, and this extraction was repeated twice. The chloroform phase was evaporated under nitrogen. For methylation, the remainder was treated with 1.5 mL sulfuric acid–methanol (1:50) at 85°C for 2 h. The mixture was diluted with 1.5 mL water and extracted with light petroleum ether. The fatty acids from the ether phase were determined using a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies 6890)/mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies 5973) with electron impact ionization and a HP-5ms capillary column (Hewlett Packard). For retention time and quantitative standardization, fatty acids purchased from Nu-Chek-Prep (Elysian, MN, USA) were used. All work was carried out under a certified ISO 9001/2000 quality system.

Plasma α-Tocopherol

Human plasma (100 μL) was diluted with 300 μL 2-propanol containing the internal standard tocol and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) as an antioxidant. After thorough mixing (15 min) and centrifugation (10 min, 4,000 × g at 10°C), an aliquot of 1 μL was injected from the supernatant into the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. HPLC was performed with a HP 1100 liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alta, CA, USA) with a HP 1100 fluorescence detector (emission 295 nm, excitation 330 nm). Tocopherol isomers were separated on a 2.1 × 250 mm reversed-phase column. The column temperature was 40°C. A two-point calibration curve was made from analysis of a 3% albumin solution enriched with known concentration of tocopherols. Recovery is >95%, the method is linear from 1 to 200 μM at least, and the limit of detection is 0.01 μM. Relative standard deviation (RSD) is 2.8% (17.0 μM) and 4.6% (25.1 μM).

Urinary F2 Isoprostanes

Fasting urine samples were analyzed for 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) by a highly specific and validated radioimmunoassay as described by Basu [17]. Urinary levels of 8-iso-PGF2α were adjusted by dividing the 8-iso-PGF2α concentration by that of creatinine.

Markers of Inflammation and Hemostasis

Plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), thromboxane B2 (TxB2), interferon-gamma (INFγ), soluble E-selectin and P-selectin, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) were determined by Fluorokine® MAP kits (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Plasma leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and thromboxane B2 (TxB2) were assessed as described by Elvevoll et al. [18]. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) evaluation was performed at the routine laboratory at Department of Medical Biochemistry at the National Hospital, Norway using standard method.

Statistics

All continuous variables were summarized by product group and visit number and described using standard statistical measures, i.e., number of observations, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum. Absolute and percentage change from baseline to the week-7 visit are presented as summary statistics. All categorical (discrete, including ordinal) variables are presented in contingency tables showing counts and percentages for each treatment group at all time points. Continuously distributed efficacy laboratory parameters (lipids, EPA, DHA, and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA)) were analyzed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using the following model: change in parameter value = baseline value + treatment + gender + age + error.

Change from baseline to week 7 was used as a dependent variable in the model. A linear model using SAS GLM with gender as fixed effect, subject as random effect, and baseline value and age as covariates was applied. A reduced ANCOVA model with baseline value and treatment was used for the secondary efficacy parameters. Significant treatment effects were analyzed by pairwise tests. Changes from baseline to end of intervention were tested by paired t-test.

Results

Subject Characteristics at Baseline

Figure 1 shows the disposition of all subjects. One hundred fifteen of 129 randomized subjects completed the study. Withdrawal rates were similar in all three groups (three withdrawals in the fish oil group, six withdrawals in the krill oil group, and five withdrawals in the control group). Three subjects discontinued the study due to clinical symptoms (all in the krill group), three subjects violated the exclusion criteria (two in the fish oil group and one in the krill oil group), and one subject in each group was lost to follow-up. Two subjects in the control group were withdrawn due to concomitant treatments, and three subjects withdrew their consent (one subject in the krill oil group and two subjects in the control group). Clinical symptoms included symptoms of common cold or gastrointestinal symptoms. During database clean-up, it was detected that two subjects (in the krill oil group) had been allowed to enter the study although they violated the entry criteria. They where therefore excluded from the per protocol subjects. The statistical analyses of efficacy were performed on the data collected from 113 per protocol subjects (Fig. 1).

The study groups were comparable in terms of weight, height, BMI, gender, and age at baseline (Table 3). Vital signs including systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were within normal ranges. More females than males were included in all study groups.

Table 3.

Demographic information and body measurements

| Parameter, mean (SD) | Study groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil (N = 43) | Krill oil (N = 44) | Control (N = 42) | |

| Age (years) | 38.7 (11.1) | 40.3 (14.8) | 40.5 (12.1) |

| Height (cm) | 171.2 (7.8) | 171.3 (8.6) | 172.2 (9.4) |

| Weight (kg) | 71.7 (12.0) | 69.8 (13.7) | 71.7 (12.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 (3.0) | 23.6 (3.3) | 23.9 (3.0) |

| Gender | |||

| Female (n) | 34 (79.1%) | 31 (70.5%) | 28 (66.7%) |

| Male (n) | 9 (20.9%) | 13 (29.5%) | 14 (33.3%) |

Fatty Acid Composition in Plasma

Plasma levels of EPA, DHA, and DPA increased significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention phase in the groups receiving fish oil and krill oil, but not in the control group. The changes in EPA, DHA, and DPA differed significantly between the subjects supplemented with n-3 PUFAs and the subjects in the control group, but there was no significant difference in the change in any of the n-3 PUFAs between the fish oil and the krill oil groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Fatty acid composition in plasma

| Parameter (μmol/L) | Treatment | N | Baseline | End of study | Change | p-Valuea for change | p-Valueb between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C14:0 myristic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 67.4 ± 57.07 | 69.4 ± 62.32 | 2.0 ± 44.05 | 0.77 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 55.5 ± 32.43 | 57.8 ± 26.15 | 2.3 ± 30.93 | 0.65 | 0.71 | |

| Control | 37 | 60.5 ± 29.25 | 58.1 ± 38.01 | −2.4 ± 35.46 | 0.69 | ||

| C15:0 pentadecanoic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 18.2 ± 14.42 | 16.2 ± 8.22 | −2.1 ± 12.01 | 0.28 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 14.7 ± 5.03 | 15.5 ± 3.69 | 0.8 ± 4.44 | 0.30 | 0.27 | |

| Control | 37 | 15.0 ± 5.02 | 15.0 ± 5.26 | 0.1 ± 4.32 | 0.94 | ||

| C16:0 palmitic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 1,661.0 ± 496.5 | 1,522. ± 339.3 | −139.0 ± 409.5 | 0.038 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 1,548.9 ± 477.9 | 1,547. ± 260.0 | −2.3 ± 414.9 | 0.97 | 0.35 | |

| Control | 37 | 1,652.7 ± 374.2 | 1,578. ± 315.6 | −74.6 ± 327.7 | 0.17 | ||

| C16:1n-7 palmitoleic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 67.7 ± 35.41 | 63.0 ± 33.54 | −4.7 ± 27.91 | 0.29 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 66.1 ± 49.18 | 61.8 ± 26.56 | −4.4 ± 35.91 | 0.47 | 0.62 | |

| Control | 37 | 68.7 ± 32.98 | 63.9 ± 35.07 | −4.8 ± 28.62 | 0.31 | ||

| C17:0 margaric acid | Fish oil | 40 | 24.2 ± 8.38 | 23.9 ± 8.44 | −0.3 ± 6.09 | 0.76 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 22.6 ± 5.85 | 24.0 ± 5.84 | 1.4 ± 5.49 | 0.14 | 0.089 | |

| Control | 37 | 23.3 ± 5.46 | 21.7 ± 5.84 | −1.6 ± 4.85 | 0.048 | ||

| C18:0 stearic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 580.6 ± 136.6 | 578.5 ± 130.2 | −2.2 ± 133.2 | 0.92 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 548.5 ± 116.7 | 568.9 ± 112.6 | 20.4 ± 91.7 | 0.19 | 0.17 | |

| Control | 37 | 594.8 ± 103.5 | 562.4 ± 147.2 | −32.4 ± 125.4 | 0.12 | ||

| C18:1n-9 oleic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 558.9 ± 166.1 | 516.2 ± 146.8 | −42.7 ± 154.0 | 0.087 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 532.8 ± 198.5 | 521.8 ± 109.1 | −11.0 ± 191.0 | 0.73 | 0.71 | |

| Control | 37 | 570.2 ± 146.8 | 547.2 ± 156.1 | −23.0 ± 151.9 | 0.36 | ||

| C18:2n-6 linoleic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 829.3 ± 349.8 | 779.8 ± 254.5 | −49.6 ± 251.3 | 0.22 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 742.0 ± 214.0 | 744.2 ± 187.9 | 2.2 ± 215.8 | 0.95 | 0.44 | |

| Control | 37 | 812.0 ± 219.6 | 735.7 ± 212.4 | −76.3 ± 167.5 | 0.0088 | ||

| C18:3n-3 alpha-linoleic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 61.7 ± 17.89 | 61.9 ± 20.22 | 0.2 ± 20.95 | 0.95 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 67.3 ± 25.24 | 68.4 ± 21.88 | 1.1 ± 20.08 | 0.73 | 0.15 | |

| Control | 37 | 68.3 ± 20.40 | 62.8 ± 22.07 | −5.5 ± 19.55 | 0.094 | ||

| C20:3n-3 eicosatrienoic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 39.6 ± 18.08 | 33.5 ± 17.97 | −6.0 ± 10.00 | 0.0005 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 39.3 ± 19.20 | 34.9 ± 13.20 | −4.4 ± 13.23 | 0.054 | 0.22 | |

| Control | 37 | 39.8 ± 18.24 | 37.7 ± 18.28 | −2.1 ± 8.65 | 0.16 | ||

| C20:4n-6 arachidonic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 192.6 ± 50.0 | 178.5 ± 45.3 | −14.1 ± 29.6 | 0.0046 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 180.1 ± 52.4 | 192.1 ± 40.2 | 12.0 ± 32.8 | 0.035 | 0.0010 | |

| Control | 37 | 189.8 ± 44.2 | 182.8 ± 38.0 | −7.0 ± 32.3 | 0.20 | ||

| C22:0 behenic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 21.5 ± 6.05 | 21.8 ± 6.36 | 0.4 ± 3.30 | 0.49 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 20.2 ± 5.29 | 22.0 ± 6.25 | 1.9 ± 3.51 | 0.003 | 0.040 | |

| Control | 37 | 18.9 ± 6.02 | 18.3 ± 4.83 | −0.6 ± 4.07 | 0.36 | ||

| C24:0 lignoceric acid | Fish oil | 40 | 10.0 ± 4.07 | 10.3 ± 4.19 | 0.3 ± 1.71 | 0.22 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 9.7 ± 2.86 | 10.4 ± 3.15 | 0.7 ± 2.04 | 0.040 | 0.26 | |

| Control | 37 | 8.9 ± 3.37 | 8.5 ± 3.05 | −0.4 ± 2.57 | 0.40 | ||

| C24:1n-9 neuronic acid | Fish oil | 40 | 18.2 ± 6.88 | 18.9 ± 6.15 | 0.6 ± 3.75 | 0.29 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 16.7 ± 5.99 | 17.3 ± 5.87 | 0.6 ± 5.00 | 0.48 | 0.17 | |

| Control | 37 | 15.7 ± 5.39 | 16.7 ± 5.70 | 1.0 ± 5.67 | 0.30 | ||

| C20:5n-3 EPA | Fish oil | 40 | 31.2 ± 23.11 | 76.3 ± 36.02 | 45.2 ± 29.65 | <0.0001 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 30.4 ± 21.57 | 74.9 ± 38.66 | 44.5 ± 35.21 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Control | 37 | 43.9 ± 40.74 | 37.2 ± 28.64 | −6.6 ± 28.58 | 0.17 | ||

| C22:6n-3 DHA | Fish oil | 40 | 47.0 ± 22.08 | 70.4 ± 25.70 | 23.4 ± 16.55 | <0.0001 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 44.8 ± 21.36 | 64.2 ± 26.15 | 19.4 ± 23.75 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Control | 37 | 57.4 ± 30.94 | 51.3 ± 23.70 | −6.1 ± 21.25 | 0.088 | ||

| C22:5n-3 DPA | Fish oil | 40 | 8.8 ± 3.98 | 12.7 ± 5.06 | 3.9 ± 3.24 | <0.0001 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 8.2 ± 3.33 | 11.9 ± 3.56 | 3.6 ± 3.68 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Control | 37 | 9.6 ± 5.09 | 8.6 ± 3.84 | −1.0 ± 3.56 | 0.090 | ||

| Total fatty acids | Fish oil | 40 | 4,250.7 ± 1,148.1 | 4,064.6 ± 890.8 | −186.0 ± 921.8 | 0.21 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 3,958.1 ± 983.7 | 4,045.5 ± 662.5 | 87.4 ± 810.7 | 0.52 | 0.15 | |

| Control | 37 | 4,261.3 ± 804.2 | 4,016.8 ± 774.4 | −244.5 ± 685.5 | 0.037 |

aTest of within-group changes

bTest comparing change from start to end of intervention between the fish oil, krill oil, and control groups

There were significant within-group changes in individual FAs from start to end of intervention, but no clear trends in changes in the plasma FA composition were apparent in any of the study groups (Table 4).

The level of arachidonic acid (C20:4n-6) increased from baseline in the krill group, whereas a decrease was observed in the fish oil group. The changes in arachidonic acid between the fish oil and the krill oil groups, and the control group differed significantly (p = 0.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that the mean increase in arachidonic acid in the krill oil group was significantly different from the mean decreases in the fish oil and control groups, but there was no significant difference between the mean changes in arachidonic acid level between the fish oil and control groups.

Serum Lipids

Small changes in the levels of HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and TG were observed in all study groups from start to end of the intervention phase, but only the within-group increase in LDL-cholesterol seen in the fish oil group (p = 0.039) was statistically significant. The tests comparing the differences between the study groups gave no statistically significant results (Table 5). The HDL-cholesterol/TG ratio and the change from start to end of the intervention were calculated for all study groups. No significant changes in the HDL-cholesterol/TG ratio from start to end of the interventions were detected in the fish oil or control groups. In the krill oil group, however, there was a significant increase in the HDL-cholesterol/TG ratio. The test for differences between the study groups gave no significant results (Table 5).

Table 5.

Serum lipids and lipoproteins

| Parameter | Treatment | N | Baseline | End of study | Change | p-Valuea for change | p-Valueb between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 1.56 ± 0.384 | 1.61 ± 0.396 | 0.05 ± 0.157 | 0.063 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 1.50 ± 0.368 | 1.63 ± 0.517 | 0.13 ± 0.404 | 0.061 | 0.50 | |

| Control | 37 | 1.59 ± 0.354 | 1.63 ± 0.395 | 0.04 ± 0.228 | 0.29 | ||

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 2.96 ± 0.747 | 3.09 ± 0.827 | 0.13 ± 0.377 | 0.039 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 3.07 ± 0.724 | 3.16 ± 0.796 | 0.09 ± 0.390 | 0.18 | 0.45 | |

| Control | 37 | 2.98 ± 0.824 | 3.03 ± 0.802 | 0.05 ± 0.361 | 0.44 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 0.95 ± 0.541 | 0.94 ± 0.542 | −0.01 ± 0.462 | 0.84 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 1.10 ± 0.638 | 1.01 ± 0.649 | −0.09 ± 0.417 | 0.21 | 0.65 | |

| Control | 37 | 0.92 ± 0.414 | 0.93 ± 0.523 | 0.02 ± 0.429 | 0.82 | ||

| HDL/triglycerides (%) | Fish oil | 40 | 225.8 ± 151.08 | 216.8 ± 119.33 | 109.5 ± 44.62 | 0.19 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 196.9 ± 134.24 | 228.3 ± 146.62 | 129.2 ± 68.99 | 0.016 | 0.41 | |

| Control | 37 | 217.7 ± 138.65 | 234.4 ± 148.20 | 113.0 ± 49.28 | 0.12 | ||

| Total-cholesterol (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 4.93 ± 0.778 | 5.13 ± 0.809 | 0.20 ± 0.424 | 0.0049 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 4.99 ± 0.815 | 5.20 ± 0.917 | 0.21 ± 0.496 | 0.014 | 0.78 | |

| Control | 37 | 4.95 ± 0.925 | 5.07 ± 0.861 | 0.12 ± 0.524 | 0.18 | ||

| Apo A1 (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 1.64 ± 0.269 | 1.68 ± 0.250 | 0.04 ± 0.130 | 0.058 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 1.64 ± 0.241 | 1.73 ± 0.376 | 0.09 ± 0.267 | 0.047 | 0.70 | |

| Control | 37 | 1.68 ± 0.272 | 1.75 ± 0.272 | 0.07 ± 0.173 | 0.023 | ||

| Apo B-100 (mmol/L) | Fish oil | 40 | 0.81 ± 0.184 | 0.80 ± 0.199 | −0.01 ± 0.100 | 0.64 | |

| Krill oil | 36 | 0.83 ± 0.208 | 0.81 ± 0.226 | −0.02 ± 0.126 | 0.35 | 0.80 | |

| Control | 37 | 0.79 ± 0.197 | 0.78 ± 0.198 | −0.01 ± 0.098 | 0.41 |

aTest of within-group changes

bTest comparing change from start to end of intervention between the fish oil, krill oil, and control groups

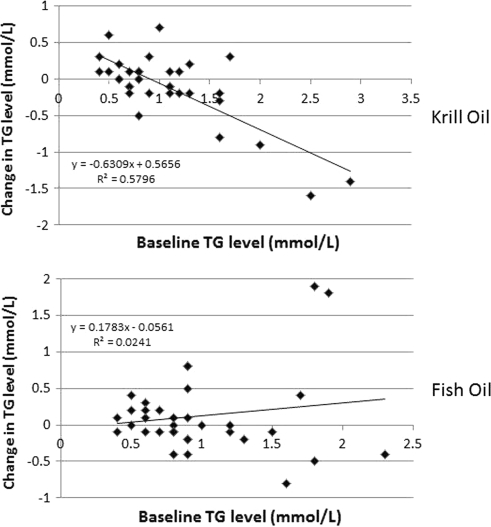

Although the interventions did not significantly change TG levels a reduction was seen in those subjects in the krill oil group having the highest baseline values (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between baseline TG levels and change in TG levels after 7 weeks of intervention with krill oil or fish oil

The changes in levels of Apo B-100 from baseline to end of study were minor in all study groups. Moreover, the test for differences between the study groups in changes in Apo A1 was not significant. However, the within-group changes of Apo A1 levels from start to end of the interventions were statistically significant in the krill oil group.

Oxidative Stress, Markers of Inflammation, and Hemostasis

α-Tocopherol is considered an antioxidant, and an increase in PUFAs may lead to increased oxidative stress. Although α-tocopherol was added to both supplements, no significant change in levels of α-tocopherol was detected (Supplementary Table). A tendency towards a reduced level of α-tocopherol was observed in all study groups. F2-isoprostanes, formed from free-radical-induced peroxidation of membrane-bound arachidonic acid, are considered a reliable biomarker of oxidative stress. However no differences were observed in urine F2-isoprostane, suggesting that there was not an increase in oxidative stress. No significant changes were observed in levels of hsCRP, markers of inflammation or hemostasis (Supplementary Table).

Discussion

The primary finding of the present study was that plasma concentrations of EPA, DPA, and DHA increased significantly in both the krill oil and fish oil groups compared with the control group following daily supplementation for 7 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference between these two groups in the levels of the increases in EPA and DHA. Since the subjects in the krill oil group received 62.8% of the total amount of n-3 PUFAs received by the subjects in the fish oil group, these findings indicate that the bioavailability of n-3 PUFAs from krill oil (mainly PL) is as, or possibly more, efficient as n-3 PUFA from fish oil (TG). This supports the results of a previous study with krill oil and menhaden oil in humans [11]. In the study performed by Maki et al., plasma EPA increased 90% and DHA increased 51% from baseline levels. In the current study EPA increased 146% and DHA increased 43% from baseline levels. The small discrepancy between these two studies might be related to different levels of EPA and DHA in the oils used, different treatment time (7 versus 4 weeks), and different dose used (3 g oil versus 2 g). It has been hypothesized that PL improve the bioavailability of lipids, which may facilitate absorption of EPA and DHA from marine PL compared with TG, but the extent to which this contributes to the efficient absorption observed in the krill oil group is unknown.

AHA dietary guidelines for long-chain n-3 PUFAs and fish for primary prevention of coronary diseases are two servings of fatty fish per week [9]. This recommendation will provide the order of 250–500 mg EPA + DHA per day [19]. In the present study we have shown that daily intake of 3 g krill oil containing 543 mg EPA + DHA increases the plasma level of EPA and DHA to the same extent as intake of fish oil containing 864 mg EPA + DHA. A food-based approach for achieving adequate intake of n-3 PUFAs is recommended [20]. However, for some individuals nutritional supplements may be needed, such as those who do not like fish or for other reasons choose not to include fish in their diet. This study demonstrates that supplementation with krill oil will be a good source of EPA and DHA in their daily diet.

Serum TG and HDL-cholesterol have been observed to be inversely related [21]. Although the metabolic relation that exists between HDL-cholesterol and TG is not fully understood, the ratio between TG and HDL-cholesterol has been shown to be a powerful risk predictor for CHD [22, 23]. In the present study, no statistically significant differences in HDL-cholesterol, TG or HDL-cholesterol/TG ratio were observed between the study groups. However, the change in the HDL-cholesterol/TG ratio in the krill oil group was statistically significant (Table 5). This observation supports the impression of a more pronounced effect of krill oil supplementation on HDL-cholesterol and TG compared with other n-3 PUFA supplements. However, to verify these effects of krill oil, they should be studied in a population with elevated blood TG levels and lowered HDL-cholesterol, i.e., in a population with markers of metabolic syndrome. The increase in HDL-cholesterol was slightly higher in the krill oil group than in the fish oil group (8.7% versus 3.2%), although not significantly so (p = 0.061). Compared with fish oil, krill oil contains a high amount of astaxanthin, which has been indicated to increase HDL-cholesterol as well as decrease TG in humans [24]. Moreover, intake of PL may increase HDL-cholesterol [25]. The small increase in LDL-cholesterol, but no effect on HDL-cholesterol, in the fish oil group is in accordance with previous findings [7].

The analysis of the changes in the plasma fatty acid composition following 7 weeks of intervention with n-3 PUFAs showed that the levels of arachidonic acid and behenic acid significantly increased from baseline in the krill oil group as compared with the fish oil and control groups. Moreover, arachidonic acid was significantly decreased in the fish oil group. Intake of n-3 PUFAs from fish oil can be incorporated in cell PL in a time- and dose-dependent manner at the expense of arachidonic acid [26]. The explanation and importance of this finding are not clear. However, one possible explanation might be that arachidonic acid is mobilized from the cell membranes to the blood by EPA and DHA linked to the PL in the krill oil. However, the changes in plasma arachidonic acid were small compared with the changes in EPA and DHA, and there was no significant difference in the increase in EPA/arachidonic acid ratio between the two intervention groups.

The CRP level did not change during the study in any of the study groups, and no significant changes were observed in the other markers of inflammation and hemostasis (data not shown). This is in accordance with others who have examined the effect of fish oil among apparently healthy individuals [27–31]. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found in α-tocopherol levels and F2-isoprostanes in urine, suggesting that no oxidative stress occurred.

The safety analysis revealed no clear patterns in the changes in any of the hematological or serum biochemical variables, vital signs or weight that might indicate a relation with administration of any of the studied products. Clinical symptoms registered during the study included mainly symptoms of common cold or gastrointestinal symptoms. However, one subject in the fish oil group experienced moderate bruises, and one subject in the krill oil group withdrew from the study because of an outbreak of rash that was possibly related to intake of the study products. Safety laboratory parameters and other safety observations such as occurrence of adverse events indicate that krill oil is well tolerated. There were no apparent differences in the rate of adverse events or blood safety parameters between the krill oil, fish oil or control groups.

In conclusion, the present study shows that n-3 PUFAs from krill oil in the form of PL are readily and effectively absorbed after ingestion and subsequently distributed in the blood. The krill oil supplement is safe and well tolerated. Krill oil thus represents a valuable source of n-3 PUFAs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the volunteers who participated in this study. This work was partially funded by Aker BioMarine ASA.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- EPA

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- DHA

Docosahexaenoic acid

- FA

Fatty acid

- PL

Phospholipids

- PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- TG

Triglycerides

References

- 1.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, Sweetnam PM, Elwood PC, Deadman NM. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2:757–761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He K, Rimm EB, Merchant A, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Fish consumption and risk of stroke in men. JAMA. 2002;288:3130–3136. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.24.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He K, Song Y, Daviglus ML, Liu K, Van Horn L, Dyer AR, Greenland P. Accumulated evidence on fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circulation. 2004;109:2705–2711. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132503.19410.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marckmann P, Gronbaek M. Fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:585–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balk EM, Lichtenstein AH, Chung M, Kupelnick B, Chew P, Lau J. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on serum markers of cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris WS. n-3 fatty acids and serum lipoproteins: human studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1645S–1654S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1645S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GISSI-Prevenzione-Investigators Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;114:82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tou JC, Jaczynski J, Chen YC. Krill for human consumption: nutritional value and potential health benefits. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:63–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maki KC, Reeves MS, Farmer M, Griinari M, Berge K, Vik H, Hubacher R, Rains TM. Krill oil supplementation increases plasma concentrations of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in overweight and obese men and women. Nutr Res. 2009;29:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnielli VP, Verlato G, Pederzini F, Luijendijk I, Boerlage A, Pedrotti D, Sauer PJ. Intestinal absorption of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in preterm infants fed breast milk or formula. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:97–103. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan C, Davies L, Corcoran F, Stammers J, Colley J, Spencer SA, Hull D. Fatty acid balance studies in term infants fed formula milk containing long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:136–142. doi: 10.1080/08035259850157552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez M, Amate L, Gil A. Absorption and distribution of dietary fatty acids from different sources. Early Hum Dev. 2001;65 Suppl:S95–S101. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(01)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemaitre-Delaunay D, Pachiaudi C, Laville M, Pousin J, Armstrong M, Lagarde M. Blood compartmental metabolism of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in humans after ingestion of a single dose of [(13)C]DHA in phosphatidylcholine. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1867–1874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyyssonen K, Kaikkonen J, Salonen JT. Characterization and determinants of an electronegatively charged low-density lipoprotein in human plasma. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1996;56:681–689. doi: 10.3109/00365519609088815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu S. Radioimmunoassay of 15-keto-13, 14-dihydro-prostaglandin F2alpha: an index for inflammation via cyclooxygenase catalysed lipid peroxidation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1998;58:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(98)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elvevoll EO, Barstad H, Breimo ES, Brox J, Eilertsen KE, Lund T, Olsen JO, Osterud B. Enhanced incorporation of n-3 fatty acids from fish compared with fish oils. Lipids. 2006;41:1109–1114. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S, Ammerican Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada (2007) Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: dietary fatty acids. J Am Diet Assoc 107:1599–1611 [PubMed]

- 21.Thelle DS, Shaper AG, Whitehead TP, Bullock DG, Ashby D, Patel I. Blood lipids in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1983;49:205–213. doi: 10.1136/hrt.49.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Luz PL, Favarato D, Faria-Neto JR, Jr, Lemos P, Chagas AC. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:427–432. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittner V, Johnson BD, Zineh I, Rogers WJ, Vido D, Marroquin OC, Bairey-Merz CN, Sopko G. The triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio predicts all-cause mortality in women with suspected myocardial ischemia: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Am Heart J. 2009;157:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida H, Yanai H, Ito K, Tomono Y, Koikeda T, Tsukahara H, Tada N. Administration of natural astaxanthin increases serum HDL-cholesterol and adiponectin in subjects with mild hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:520–523. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien BC, Andrews VG. Influence of dietary egg and soybean phospholipids and triacylglycerols on human serum lipoproteins. Lipids. 1993;28:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02536352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibney MJ, Hunter B. The effects of short- and long-term supplementation with fish oil on the incorporation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids into cells of the immune system in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993;47:255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geelen A, Brouwer IA, Schouten EG, Kluft C, Katan MB, Zock PL. Intake of n-3 fatty acids from fish does not lower serum concentrations of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1440–1442. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vega-Lopez S, Kaul N, Devaraj S, Cai RY, German B, Jialal I. Supplementation with omega3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and all-rac alpha-tocopherol alone and in combination failed to exert an anti-inflammatory effect in human volunteers. Metabolism. 2004;53:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madsen T, Christensen JH, Blom M, Schmidt EB. The effect of dietary n-3 fatty acids on serum concentrations of C-reactive protein: a dose-response study. Br J Nutr. 2003;89:517–522. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yusof HM, Miles EA, Calder P. Influence of very long-chain n-3 fatty acids on plasma markers of inflammation in middle-aged men. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;78:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujioka S, Hamazaki K, Itomura M, Huan M, Nishizawa H, Sawazaki S, Kitajima I, Hamazaki T. The effects of eicosapentaenoic acid-fortified food on inflammatory markers in healthy subjects—a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2006;52:261–265. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.52.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.