Abstract

Ligand-induced proteolysis of Notch produces an intracellular effector domain that transduces essential signals by regulating target gene transcription. This function relies on formation of transcriptional activation complexes that include intracellular Notch, a Mastermind co-activator, and the CSL transcription factor bound to cognate DNA. These complexes form higher order assemblies on paired, head-to-head CSL recognition sites. Here, we report the X-ray structure of a dimeric human Notch1 transcription complex loaded on the paired site from the human HES1 promoter. The small interface between the Notch ankyrin domains can accommodate DNA bending and untwisting to allow a range of spacer lengths between the two sites. Remarkably, cooperative dimerization occurs on the Hes5 promoter at a sequence that diverges from the CSL-binding consensus at one of the sites. These studies reveal how promoter organizational features control cooperativity and thus, the responsiveness of different promoters to Notch signaling.

Notch proteins are highly conserved transmembrane receptors that regulate numerous developmental events through cell-cell contact in multicellular organisms. The importance of Notch as a developmental regulator in mammals is underscored by the developmental defects and embryonic lethality associated with loss-of-function of core components of the Notch pathway in both mice and humans1. The requirement for tight control of Notch activity is also highlighted by the association of dysregulated Notch activity with cancer. Most notably, mutations in human Notch1 that lead to increased Notch signaling activity are found in more than half of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphomas2.

Notch receptors are normally activated by regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP)3. After engagement with ligand, Notch becomes sensitive to metalloprotease cleavage at a juxtamembrane site 2 (refs. 4,5), resulting in ectodomain shedding. This step creates a transient membrane-tethered species that is subsequently cleaved by the γ-secretase multiprotein enzyme complex6–10 to release the intracellular portion of Notch (ICN, NICD or Notch-Intra) from the membrane, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus. There, it assembles into a DNA-bound Notch transcription complex (NTC) that also contains two other proteins: a ubiquitous DNA-binding transcription factor called CSL (named for CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, and LAG-1; refs. 11,12), and a co-activator of the Mastermind family (Mastermind-like or MAML in mammals)13–16.

Purified mammalian and worm CSL proteins bind as monomers to DNA in a sequence-specific fashion; the consensus sequence that mammalian CSL binds to is (C/A/T)(G/A)TG(G/A/T)GAA16. Structures of mammalian and worm multiprotein complexes containing portions of Mastermind, ICN, and CSL on cognate DNA have further revealed that the ankyrin domain of Notch (ANK) and a REL-homology domain of CSL create a composite binding site for the N-terminal region of Mastermind-like coactivators17,18; however, the binding of ICN and Mastermind-like proteins neither produces any new protein-DNA contacts, nor perturbs existing ones between CSL and DNA19.

Although CSL–ICN–MAML complexes can bind DNA as monomers, several well-characterized Notch target genes have more than one CSL-binding site in their proximal promoters. In particular, the promoters of some Drosophila and mammalian HESR (Hairy/Enhancer of Split related) genes contain a conserved pair of CSL binding sites in a psuedo-symmetrical head-to-head orientation that are separated by 15–19 base pairs, a type of element termed a Su(H)-paired site or sequence paired site (SPS)20–22. Disruption of a SPS by mutation of either site, inversion of a site, or insertion or deletion of base pairs between the sites abrogates Notch-dependent gene transcription in cell based assays and transgenic flies20,23.

Though the X-ray structures explain how Notch nuclear effector complexes readily assemble onto DNA containing a single CSL binding site, how the arrangement of multiple CSL binding sites influences the transcriptional activity of various Notch-responsive promoters has remained elusive. Some progress into understanding how cooperativity might take place has emerged from consideration of crystal contacts between two copies of the ANK domain related by a 2-fold symmetry axis18 in the structure of the human monomeric complex.

The interface between the symmetry-related complexes orients their respective single-site DNA duplexes head-to-head in a near-linear orientation about 65 Å apart. Biochemical studies showed that mutation of interacting residues at the crystal-packing interface of the Notch intracellular domains (NICD) disrupts cooperative complex assembly on the human HES1 SPS24. However, when modeled onto the human HES1 SPS as ideal B-form DNA, NICD residues implicated in higher order complex assembly lie almost 50 Å apart (Supplementary Fig. 1). If the observed contacts in the pseudo-dimer crystal indeed represent the actual dimer interface, then the two NTCs, the DNA to which they are bound, or both must undergo a substantial conformational change to bring the dimerization interfaces of the two complexes into close proximity when bound to an SPS.

To reveal the topology of Notch transcription complexes bound to an actual SPS, we determined the X-ray structure of a human Notch1 ANK–CSL–MAML1 dimeric complex bound to hHES1 paired-site DNA. To complement the structural studies, we also investigated the dimerization-dependence of other Notch target genes with clustered CSL binding sites in biochemical studies and reporter gene assays. These studies revealed one subset of Notch responsive promoter elements that are dimer-independent, represented by mHey2 and hHEYL. Our studies also uncovered a conserved, cryptic paired element in the mouse and human Hes5 promoter that supports cooperative assembly of dimeric Notch transcription complexes, even though the target DNA sequence diverges substantially from the CSL-binding consensus at one of the two paired sites, suggesting that some Notch-responsive promoters may be dimerization-dependent despite the absence of recognizable paired sites. Together these studies elucidate how cooperativity in the formation of Notch transcription complexes can act as a critical control point to regulate the transcriptional response of different promoters to Notch activation.

Results

The structure of the Notch1 ANK–CSL–MAML1 dimeric complex bound to hHES1 paired-site DNA was solved by molecular replacement to 3.45 Å resolution (Table 1). The final model includes two CSL–ANK–MAML1 complexes (NTCs) bound to a 37 base pair DNA oligonucleotide. Residues 12–434 of CSL, residues 1921–2119 of Notch1, and residues 16–70 of MAML1 are all built for both copies of the NTC, and all of the DNA is resolved in the final model (Table 1). The first ankyrin repeat of Notch1, which is partially ordered in the structure of a monomeric NTC on single-site DNA, is not observed for either copy of the Notch1 ANK domain in this structure.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Dimeric NTC on hHES1 DNA | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 295.11, 108.06, 87.24 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 102.52, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50−3.45 (3.51−3.45)* |

| R sym | 0.063 (0.393) |

| I / σI | 30.7 (4.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 9.5 (7.2) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 45.02−3.45 (3.54−3.45) |

| No. reflections | 33559 (2394) |

| Rwork / Rfree | 25.1/30.0 |

| No. atoms | 12204 |

| Protein | 10692 |

| DNA | 1512 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 122.5 (ANK, 94.4; CSL, 135.3; MAML, 121.7) |

| DNA | 174.4 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.699 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Complex architecture

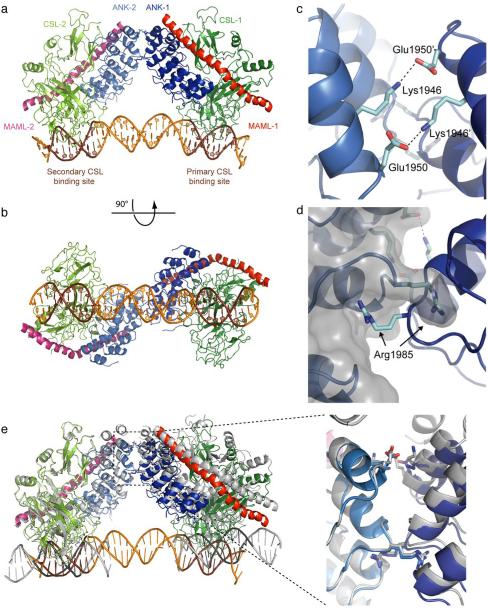

The protein complex assembles as a dimer of heterotrimers exhibiting two-fold symmetry on the sequence paired site (SPS) DNA, with the two CSL protein subunits anchoring the protein assembly to the DNA at the two binding sites in a head-to-head orientation (Fig. 1a, b). Contacts between the two NTCs are only observed on the convex face of the Notch1 ANK domains, with little conformational change in each individual NTC trimer upon dimer formation. To bring the two ANK domains into contact with each other, the hHES1 paired-site DNA bends and untwists substantially relative to B-form DNA, with an average helical twist of 34.3° across each base of the 16 base-pair spacer that results in a cumulative untwisting of 28° across the DNA spacer between the two CSL sites.

Figure 1.

Structure of a dimer of Notch transcription complexes on paired-site DNA. (a) Ribbon representation of two copies of the Notch1 ANK–CSL–MAML1 complex on the paired-site DNA element from the human HES1 promoter. The NTC complex bound to the primary CSL binding site (TGTGGGAA) contains ANK (blue), CSL (green), and MAML1 (red). The complex bound to the secondary CSL binding site (CGTGTGAA) includes a second molecule of ANK (light blue), CSL (chartreuse) and MAML1 (pink). The DNA is colored orange with the two CSL binding sites highlighted in brown. (b) A view related by a 90° rotation around the DNA axis of panel (a). (c, d) Interactions in the NTC dimer interface, including salt-bridges between Lys 1946 of one Notch ANK domain and Glu 1950 of the other ANK domain (c), and between Arg 1985 of one Notch ANK domain and a pocket created by Arg 1985 and surrounding residues in the other ANK domain (d). (e) Comparison of the NTC dimeric structure to the crystallographic pseudo-dimer seen for two symmetry mates in 2F8X (grey)18. The panel to the right shows a zoomed view of the superimposed dimer interface.

Features of the interface between the ANK domains

The two NTCs contact each other via Notch1 ankyrin domain interactions that exhibit 2-fold symmetry perpendicular to the DNA helical axis. The three residues previously implicated in dimerization of NTC complexes, Arg1985, Lys1946, and Glu1950, all make direct contact at this ANK–ANK interface in the complex. Arg1985 of one ANK domain packs into a pocket created by Arg1985 and surrounding residues of the adjacent ANK domain, while Lys1946 of each ANK subunit forms a salt-bridge to Glu1950 of the other subunit (Fig. 1c, d).

A comparison of the structure of the naturally-occurring NTC dimer bound to the hHES1 paired site to that of the pseudo-dimer created at the crystal-packing interface of NTCs bound on single-site DNA24 also provides insight into how NTC dimers might form on DNA response elements with different spacer lengths (Fig. 1e). Whereas superposition of one ANK domain of the true dimer onto an ANK domain of the symmetry-related pseudo-dimer reveal that the alpha carbon atoms of Arg1985 and the Lys1946–Glu1950 residues engaged in salt bridge contacts nearly superimpose on one another, a substantial displacement is observed in the relative orientations of the CSL and MAML molecules in the second complex of the true dimer when compared with the pseudo-dimer. The entire NTC in the second copy of the native dimer is twisted relative to the second NTC of the pseudo-dimer, shifting the position of the CSL protein by 12–17 Å at its contact point with the DNA so that it occupies its preferred binding site (Fig. 1e). Since the same protein contacts are maintained at both dimer interfaces, the evolution of the ANK–ANK interface had to maintain the integrity of the dimer interface while accommodating different degrees of twist and bending angles of the DNA, necessitated by the varying distances between the two CSL binding sites in different promoter elements (15–18 base-pairs)20,22,24.

Dimer-dependence of SPS elements in other Notch-responsive genes

To explore the range of naturally occurring promoter sequences that might load NTC complexes cooperatively onto DNA, we first identified several putative Notch targets with paired sites in their proximal promoters, defined as sequences up to 5 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site. In our initial search of the human genome, we restricted consideration to paired sites that had a 16 base-pair spacer, because this distance is the spacing seen in the mouse and human HES1 paired site. Genes with sequences fitting these criteria include hHES4 and hFJX125, which have two predicted CSL binding sites (Fig. 2a) separated by spacers with relatively high GC content (69% and 81%, respectively) compared to the spacer in the HES1 SPS (38%). We then tested whether NTCs cooperatively dimerized on the SPS elements from these two promoters using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Fig. 2b). For these studies, we utilized a region of intracellular Notch1 that includes both the RAM and ANK regions of the protein (RAMANK). On a DNA probe containing a single CSL binding site, both wild-type RAMANK and the R1985A mutant readily assemble into ternary DNA-bound complexes with CSL and MAML. When the probes are composed of DNA sequences with the SPS architecture (two CSL sites oriented head to head with a spacer of 16 base-pairs), CSL alone binds non-cooperatively to the DNA, with most probes loading a single copy of the CSL protein. The addition of either wild-type or R1985A RAMANK supershifts the CSL bands without substantially altering the stoichiometry of singly and doubly bound probe molecules. Upon addition of MAML1 to wild-type RAMANK–CSL–DNA complexes, there is a dramatic change in the stoichiometric distribution of complexes; all of the DNA probe molecules are either free or in a higher molecular weight NTC dimeric complex, demonstrating cooperativity in the assembly of these higher order complexes when MAML1 is present. In contrast, addition of MAML to R1985A RAMANK–CSL–DNA complexes does not produce this single higher-order complex (see also ref. 24). These studies show that NTCs containing wild-type ICN1, but not the R1985A dimer-defective mutant, undergo cooperative dimerization on these sites.

Figure 2.

NTC dimer formation on putative Notch targets hHES4 and hFJX1 and on SPS elements with 15–17 bp spacers. (a) Oligonucleotide duplexes used for Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays. (b) EMSAs performed using CSL, MAML1 and wild-type Notch1 RAMANK or R1985A on SPS elements from the promoters of putative Notch target genes, hHES4 and hFJX1. Schematic representation of the complexes assembled include CSL (green), RAMANK (blue) and MAML1 (red) on DNA (grey). (c) EMSAs performed on DNA with CSL sites in the SPS arrangement with spacers of 16 bp (the HES1 SPS), 15 bp (from the SYT14 promoter) and 17 bp (from the CUL1 promoter).

To extend these findings, we identified other naturally occurring SPS elements in the human genome with a range of spacer lengths between the two CSL sites and tested whether these elements also bound NTC dimers cooperatively in our electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Fig. 2c). These studies show that intersite spacers of 15–17 base-pairs also permit cooperative loading of higher-order complexes, consistent with our previous biochemical studies analyzing mutated forms of the human HES1 SPS24.

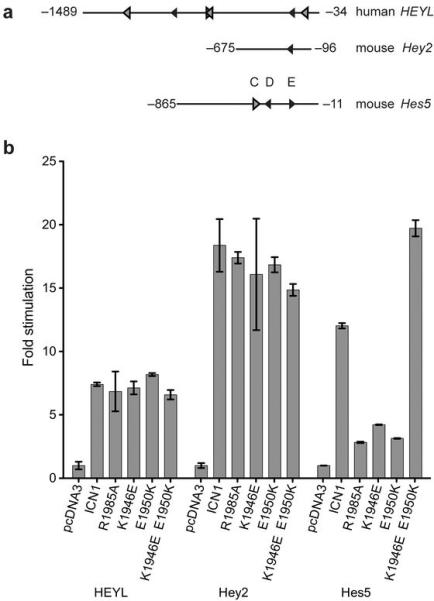

Dimerization dependence of target genes without a canonical SPS

To explore whether other well-established Notch transcriptional targets might rely on formation of dimeric ICN-CSL-MAML complexes, we tested a panel of known Notch responsive genes23,26 for their dimerization-dependence using a collection of dimerization-competent and dimerization-deficient forms of activated Notch in luciferase reporter gene assays (Fig. 3). These studies revealed two distinct classes of Notch-responsive proximal promoters. The first class, represented by hHEYL and mHey2 (Fig. 3a), do not exhibit any detectable dimerization dependence (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, the second class, represented by mHes5 (Fig. 3a), shows a dramatic decrease in reporter activity when transfected with dimerization incompetent forms of activated Notch (R1985A, K1946E, and E1950K). The charge-swapped double mutant K1946E/E1950K, which restores dimerization competence, rescues this reduction in activity (Fig. 3b). To test the role of dimerization in ligand dependent signaling, we also examined the responsiveness of the promoter elements from hHES1, mHes5, mHey2, and hHEYL, and the strong TP1 response element (predicted to be dimerization independent) to full-length Notch1 and to the R1985A dimerization-deficient mutant. Two different sets of experiments were performed: one with immobilized DLL1 ligand and the other with CHO cells expressing DLL1 ligand. The results from these studies show that the conclusions derived from the reporter assays carried out with intracellular Notch also hold for the full-length receptors in a ligand-dependent configuration (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Together, these findings show that formation of dimeric Notch complexes contributes to the observed transcriptional activation of the hHES1 and mHes5 reporters, but not to that of hHEYL or mHey2 reporters.

Figure 3.

Dimer-dependent and dimer-independent DNA elements identified in the promoters of Notch responsive genes hHEYL, mHey2 and mHes5. (a) Diagram of the promoter elements used to control the expression of luciferase reporter genes. Predicted high affinity CSL binding sites (black arrowheads) and low affinity sites (grey arrowheads) are depicted with the direction of the arrowhead representing the relative orientation of the CSL binding site. (b) Responsiveness of luciferase reporter genes under control of hHEYL, mHey2, or mHes5 promoter elements upon expression of various activated Notch1 receptors (see methods). Fold stimulation is expressed relative to empty vector control, which is set to a value of 1. Error bars correspond to standard deviations.

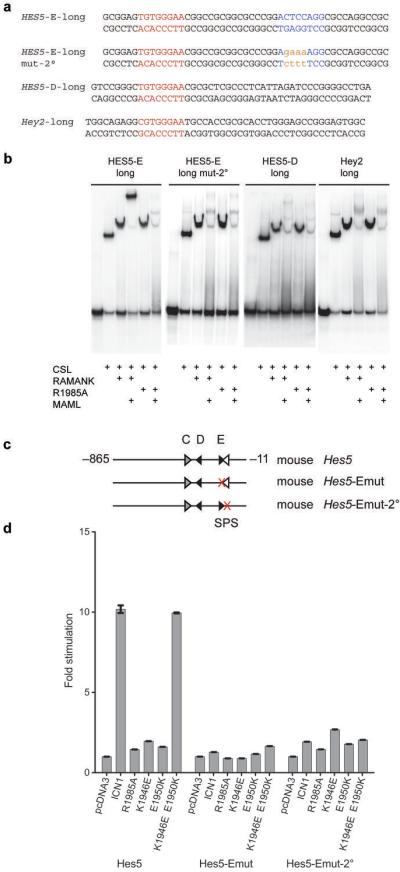

Although the conserved mouse and human Hes5 promoters have several consensus CSL binding sites clustered in the proximal promoter region23, none are partnered with a consensus second site in an SPS arrangement. To identify the origin of the observed dimer-dependence of the Hes5 promoter, we performed a series of complementary gel shift experiments and reporter assays. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays first confirmed that NTCs assemble on isolated D and E site sequences (Fig. 4a,b), which are the two sites most proximal to the transcriptional start site (see Fig. 4c). The reporter assays then confirmed that only the integrity of site E (the most proximal consensus site) is essential for transcriptional activation by all forms of ICN1, as mutation of this site (Emut) results in almost complete loss of activity in the reporter assay (Fig. 4d and ref. 23). In contrast, mutation of the upstream site D has a much less pronounced effect on reporter activity (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the dimerization dependence of this activity is retained in the promoter with the D site mutation, indicating that the E site harbors the dimerization-responsive element.

Figure 4.

The mouse and human HES5 proximal promoters each contain two conserved high affinity CSL binding sites, one of which is essential for activation of expression. (a) HES5 D and E site single CSL site oligonucleotide duplexes (which have identical CSL binding sites and are conserved between mouse and human) used for EMSAs. (b) EMSAs performed on single CSL site DNA from the D and E sites of the human HES5 promoter. (c) Diagram of the promoter elements used to control expression in luciferase reporter constructs. Predicted high affinity CSL binding sites (black arrowheads) and low affinity sites (grey arrowheads) are depicted with the direction of the arrowhead representing the relative orientation of the CSL binding site. Mutated CSL binding sites are indicated by a red X. (d) Luciferase reporter assays performed on the Hes5-Dmut and Hes5-Emut response elements using the indicated forms of ICN1. Fold stimulation is expressed relative to empty pcDNA3 vector control, which is set to a value of 1. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Identification of a cryptic SPS in the mouse and human Hes5 promoters

The above observations suggested that a second, “cryptic” paired CSL-binding site might exist in the head-to-head orientation 15–17 base pairs from the primary E site. To test this hypothesis, we first extended the E-site DNA sequence used in the mobility shift assay to encompass the proposed secondary site, and tested the mouse and human versions (which differ at 1 base-pair in the putative secondary binding site) for the ability to cooperatively load higher order Notch complexes (Fig. 5a, b, human E site and Supplementary Fig. 3, mouse E site). This analysis confirmed that the extended E-site sequence did indeed support cooperative assembly of higher order Notch transcription complexes, and that this cooperativity was lost when the R1985A mutation was used to disrupt the dimerization interface. In contrast, extended Hes5 D-site and mHey2 sequences (Fig. 5a) did not promote the cooperative formation of higher order complexes or alter the loading of wild-type ICN1 or the R1985A mutant from of ICN1 onto DNA (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Identification of a non-consensus SPS element in the HES5 promoter. (a) Long oligonucleotide duplexes used for EMSAs, spanning the primary CSL binding site and flanking sequence. 2°: secondary site. (b) EMSAs performed on the DNA sequences in (a) using CSL, MAML1 and wild-type Notch1 RAMANK or R1985A RAMANK as indicated. (c) Diagram of the promoter elements used to control expression in luciferase reporter constructs. Predicted high affinity CSL binding sites (black arrowheads), low affinity sites (grey arrowheads) and the cryptic binding site (white arrowhead) are depicted with the direction of the arrowhead representing the relative orientation of the CSL binding site. Mutated CSL binding sites are indicated by a red X. (d) Luciferase reporter assays, performed on the normal mHes5 promoter or on promoters with mutations at the primary or cryptic secondary CSL binding sites (mHes5-Emut or mHes5-Emut-2°) using the indicated forms of ICN1. Fold stimulation is expressed relative to empty pcDNA3 vector control, which is set to a value of 1. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To further evaluate the role of the secondary site, we tested the effects of mutating this site on reporter gene transcription and on cooperative dimerization in the mobility shift assay (Fig. 5). The secondary site mutation (Emut-2°) abrogates ICN1 responsiveness in the reporter assays to the same extent as mutation of the primary E site (Emut) (Fig. 5c,d). The same mutation in the context of extended hHES5 E-site DNA also prevents higher order complex formation in the mobility shift assay without affecting the loading of an NTC onto the primary CSL binding site (Fig. 5a,b). Together, these studies argue that the dimerization-dependence of the Hes5 promoter results from the presence of a low affinity CSL binding site that in the context of the flanking high affinity E-site creates a cryptic SPS response element. Importantly, mHes5 promoter constructs containing this cryptic site but missing elements upstream to the E site are not fully active23, suggesting that unlike the HES1 SPS, this cryptic site alone is not sufficient for full transcriptional output.

Discussion

Here, we report the structure of a dimeric NTC on paired-site promoter DNA from the HES1 gene, and show that dimeric NTCs can form cooperatively on a cryptic paired site from the mouse and human Hes5 promoter. Our studies also identify examples of dimer-independent and dimer-dependent promoter elements, providing new insights into the intrinsic biochemical factors likely to govern the transcription response of target genes to Notch in different developmental, physiologic, and pathophysiologic contexts.

The structure reveals the mode by which NTCs cooperate to bind paired-site DNA elements. The dimer interface is restricted to the Notch ANK domain, and buries a modest surface of less than 500 Å2 on each ANK molecule. By utilizing a limited contact interface, the two NTCs can rotate relative to each other to accommodate longer or shorter spacers between the two CSL binding sites, supporting the idea that there is some flexibility in spacer lengths between sites.

Recent studies showed that the affinity of CSL for the high affinity site in the HES1 SPS (TGTGGGAA) was twice as strong as that seen for the second site (CGTGTGAA; ref. 27). Similarly, we observe cooperative dimer formation on SPS elements with a range of predicted individual site affinities. One important consequence of variation in the details of paired sites may well be differential tuning of the threshold for assembly of dimeric Notch transcription complexes in response to Notch activation, but the weight of this input relative to other variables is not clear. Computational searches aiming to map potential SPS elements in the regulatory regions controlling transcription of Notch target genes may also need to loosen the definition of the second site consensus motif to account for these observations.

Although no direct contacts between MAML proteins are observed in the structure, cooperative dimerization of NTCs is MAML-dependent. One possible explanation for this dependence is that the ANK domain of Notch is dynamic in the absence of MAML, exchanging between CSL-bound and free positions upon engagement of CSL by the RAM polypeptide. In this model, addition of MAML would then lock the ANK domain into the position seen in the crystal structures of Notch transcription complexes. This model is consistent with the small buried surface area at the ANK–ANK dimer interface, and the failure of the Notch1 ANK domain alone to form dimers in solution at typical intracellular protein concentrations18,28. Though fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assays do show that the ankyrin domain of RAMANK molecules do sample the closed conformation in the context of RAMANK–CSL–DNA complexes29, this finding remains compatible with the possibility of a dynamic ANK–CSL interaction in the absence of the MAML polypeptide. Further examination of the effect of MAML on ANK–CSL interactions at the single-molecule level may help to explain its critical importance.

Our cell-based assays also reveal the existence of two kinds of Notch response elements: those that are dimerization dependent and those that are dimerization independent. There are a number of potential mechanistic explanations for dimerization dependence at some sites but not others. One possibility is that dimerization is needed for effective displacement of repressors such as Ikaros family proteins, which are important negative regulators of Notch transcriptional targets in certain cell types and which have binding-site preferences that overlap with those of CSL30. Formation of dimeric complexes might also increase the duration of DNA binding-site occupancy though an avidity effect. This mechanism might be needed in the case of Notch transcription complexes because the affinity of CSL for consensus DNA binding sites is relatively low when compared to other transcription factors27. It is also possible that dimeric complexes in the paired-site arrangement either directly or indirectly recruit additional proteins, such as E-box binding proteins (see e.g. ref. 20) that drive the transcriptional response, and that monomeric target genes recruit additional factors through different mechanisms. Structurally undetermined regions N-terminal to the ankyrin domain of Notch, the N-terminal region of MAML, and the C-terminus of CSL are in all in close proximity to the putative dimerization interface of ANK. It seems possible, therefore, that flanking regions of Notch, CSL, and MAML may enhance dimerization of NTCs or provide a new composite surface for accrual of additional factors.

Finally, complementary studies of murine models for T-cell development and leukemogenesis highlight the relevance of NTC dimerization in vivo31. Bone-marrow transplantation of hematopoetic precursors expressing both wild-type ICN1 and the R1985A mutant both support T cell fate specification from a multipotential precursor. However, only ICN1 supports full T-cell maturation in this model. Moreover, hematopoetic precursors expressing normal ICN1 rapidly induce leukemia with virtually 100% penetrance when introduced into lethally irradiated mice, whereas the R1985A mutant fails to induce leukemia at all in this model. These data strongly support the presence of both dimer-dependent and dimer-independent Notch transcriptional targets in both physiologic and pathologic contexts. Thus, the dimerization interface itself presents a potential new target for therapeutic manipulation that would be selective for certain, but not all, Notch-dependent cellular functions.

Materials and Methods

Protein purification and complex assembly

Notch complexes containing the ankyrin domain of human Notch1 (1873–2127), CSL (9–435), and MAML (13–74) have been produced and purified as described with minor modifications18,28. Protein complexes are assembled by combining MAML, ANK and CSL and buffer exchanging into 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT and purified by size-exclusion chromatography. Duplex DNA is generated by annealing complementary oligonucleotides at 100°C for 5 min and slowly cooling to room temperature. Purified trimeric protein complexes are mixed with DNA including the HES1 SPS element in a ratio of protein to DNA of 2:1.2.

Crystallization

Small crystals were observed in trials with NTCs with several oligonucleotide duplexes varying in length from 35–43 base-pairs. After optimization, the largest and best diffracting crystals included a 37-mer with a 1 base overhang, (HES1-36-1o, TACTGTGGGAAAGAAAGTTTGGGAAGTTTCACACGAG, ACTCGTGTGAAACTTCCCAAACTTTCTTTCCCACAGT). Dimeric NTC on HES1-36-1o crystallized by vapor diffusion using the hanging drop method in 3% (w/v) PEG3350, 10% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 0.1M MgCl2, 0.1M Bis-Tris pH 6. Crystals were transferred to cryoprotectant (5% (w/v) PEG3350, 25% (w/v) ethylene glycol, 0.1M MgCl2, 0.1M BisTris pH 6) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline 24-ID-C (NE-CAT). Crystals diffracted to 3.45 Å (Table 1).

Structure Determination

The structure was solved by molecular replacement (MR), using the protein components of the Notch1 transcription complex, ANK–CSL–MAML1, 2F8X18. After MR, density for DNA was observed indicating that a correct solution had been found. A nearly complete model for the protein–DNA complex has been built. The initial refinement was performed with strict non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) between the two protein trimers and restraints on DNA geometry. Rounds of refinement using CNS32 or REFMAC33 were alternated with rounds of manual building in COOT34 into density from Fo-Fc maps and simulated-annealing composite-omit maps. The final model, after REFMAC refinement, has tight NCS restraints. Residues 12–434 of CSL, residues 1921–2119 of ICN, and residues 16–70 of MAML have been built for both copies of the NTC in the structure. All of the DNA has been built. One end of the DNA duplex packs against itself at a 2-fold symmetry axis. The other end of the DNA packs against protein with the 1 base overhang flipped out and the first base pair packed against a tryptophan. The HES1 DNA in this crystal is non-palindromic and pseudo-symmetrical, and because the data diffracts only to a spacing of 3.45 Å, it is not possible to orient the DNA based on its electron density alone. Crystallization of NTC dimers on HES1 DNA with an overhang at one end and at the other a blunt end, was undertaken. This complex crystallized in the same space group and with a slightly elongated unit cell in the dimension parallel to the DNA, compared to the original HES1 duplex with overhangs at both ends. By comparison of the packing at the DNA ends of these two structures, we chose to orient the DNA such that the 2-fold DNA contacts involved the 1 base overhang shared in both structures.

EMSAs

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays were performed as described with minor modifications35. Double-stranded 32P-labelled DNA was prepared by 5' filling of annealed oligonucleotides with Klenow in the presence of 32P-labelled dCTP. Each duplex was designed to incorporate at least three labeled cytosine nucleotides, and non-wild-type nucleotides were added to the ends when necessary to achieve equivalent labeling between duplexes. Labelled DNA was incubated with protein for 30 min at 30°C in a 15 μl volume containing Hepes buffer (20 mM, pH 7.9), KCl (60 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), DTT (10 mM), BSA (0.2 mg ml−1), dGdC (200 ng), and 10% (v/v) glycerol. Typically, 0.4 pmol DNA is mixed with 5–15 fold excess CSL(9–435), and excess of wild-type or mutant RAMANK(1761–2127) and MAML(13–74). Samples were electrophoresed at 180 V on 10% Tris-glycine-EDTA gels. Gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography. Double-stranded DNA used for EMSAs: Human HES4, GGCGAGTGTGGGAAAGAATGCGGAGCCGGGTTCACACACCCCGCGG; human FJX1, GGACCTGTGAATCGCGCCCACCGGAGGGTCTCACAAGC; mouse and human HES1, AGTTACTGTGGGAAAGAAAGTTTGGGAAGTTTCACACGAGCCGTTC; Single-site control, GGAAACACGCCGTGGGAAAAAATTTGGC; 15bp (human chr1: 206494991 f,SYT14 promoter), GCCAAACATGGGAAATTGCTGCTATTCTTTTCCCACTACAGCC; 17bp (human chr7: 147828581 f, CUL1 promoter), GAATTACGTGGGAATTATAAATAAATTACTCTTCACACTCTTATCC; human HES5_E_single, GGAGGCCGCGGAGTGTGGGAACGGCCGCGGCAGC; mouse and human HES5_D_single, GGAGGCGAGCGCGTTCCCACAGCCCGGACATAGC; mouse and human HES5_D_long, TCAGGCCCCGGGATCTAATGAGGGCGAGCGCGTTCCCACAGCCCGGAC; human HES5_E_long, GCGGAGTGTGGGAACGGCCGCGGCGCCCGGACTCCAGGCGCCAGGCCGC; human HES5_E_long_mut2°, GCGGAGTGTGGGAACGGCCGCGGCGCCCGGAgaaaAGGCGCCAGGCCGC; mouse Hes5_E_long, GCCGAGTGTGGGAACGGCCGCGGCGCCCGGACCCCAGGCGCCGGGCCGC, mouse and human HES5_D_long, TCAGGCCCCGGGATCTAATGAGGGCGAGCGCGTTCCCACAGCCCGGAC; mouse Hey2_long, GCCACTCCCGGCTCCCAGGTGCGCGGTGGCATTCCCACGCCTCTGCCA;

Reporter Assays

Luciferase reporter assays were performed using modified versions of published protocols23,35,36. In 24-well or 96-well plates, 3T3, HeLa, or U2OS cells were transfected with either pcDNA3 vector expressing wild-type or mutant Notch1-ICN or pCS2 vector expressing wild-type or mutant Notch1deltaE and pLUC+ or pGL2 luciferase reporter plasmids. Reporter plasmids consisting of wild-type or mutant segments of the proximal promoters of mHes5 (−865 to −11, relative to start codon) in pGL223, mHey2 (−675 to −96), and hHEYL (−1489 to −34) in pLUC+ were used23,26. Cells were harvested 24–48 hours after transfection. For each reporter, fold stimulation is expressed relative to the activity of the empty vector control, which is normalized to a value of 1. All data points were obtained in duplicate (mHey2 and hHEYL) or triplicate (mHes5) and error bars correspond to standard deviations. The data reported in the figures are representative of three independent experiments in each case. Equivalent results are observed for Hes5 reporter assays performed in 3T3, HeLa and U2OS cells and for Hey2 and HEYL reporter assays performed in 3T3 and HeLa cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Warren Pear for helpful discussions and for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA-092433 (to S.C.B.) and CA-119070 (to S.C.B. and J.C.A.). K.L.A. is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the American Cancer Society. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Database Accession Numbers. Protein Data Bank: Coordinates have been deposited with accession code 3NBN.

References

- 1.Gridley T. Notch signaling and inherited disease syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(Spec No 1):R9–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng AP, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, Goldstein JL. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000;100:391–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mumm JS, et al. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brou C, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Y, Lukinova N, Fortini ME. Neurogenic phenotypes and altered Notch processing in Drosophila Presenilin mutants. Nature. 1999;398:525–9. doi: 10.1038/19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe MS, et al. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;398:513–7. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Struhl G, Greenwald I. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature. 1999;398:522–5. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Strooper B, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398:518–22. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–6. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen S, Kodoyianni V, Bosenberg M, Friedman L, Kimble J. lag-1, a gene required for lin-12 and glp-1 signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to human CBF1 and Drosophila Su(H) Development. 1996;122:1373–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortini ME, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The suppressor of hairless protein participates in notch receptor signaling. Cell. 1994;79:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, et al. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–9. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petcherski AG, Kimble J. Mastermind is a putative activator for Notch. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R471–3. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petcherski AG, Kimble J. LAG-3 is a putative transcriptional activator in the C. elegans Notch pathway. Nature. 2000;405:364–8. doi: 10.1038/35012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tun T, et al. Recognition sequence of a highly conserved DNA binding protein RBP-J kappa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:965–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JJ, Kovall RA. Crystal structure of the CSL-Notch-Mastermind ternary complex bound to DNA. Cell. 2006;124:985–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam Y, Sliz P, Song L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for cooperativity in recruitment of MAML coactivators to Notch transcription complexes. Cell. 2006;124:973–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovall RA, Hendrickson WA. Crystal structure of the nuclear effector of Notch signaling, CSL, bound to DNA. Embo J. 2004;23:3441–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cave JW, Loh F, Surpris JW, Xia L, Caudy MA. A DNA transcription code for cell-specific gene activation by notch signaling. Curr Biol. 2005;15:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nellesen DT, Lai EC, Posakony JW. Discrete enhancer elements mediate selective responsiveness of enhancer of split complex genes to common transcriptional activators. Dev Biol. 1999;213:33–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey AM, Posakony JW. Suppressor of hairless directly activates transcription of enhancer of split complex genes in response to Notch receptor activity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2609–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong CT, et al. Target selectivity of vertebrate notch proteins. Collaboration between discrete domains and CSL-binding site architecture determines activation probability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5106–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam Y, Sliz P, Pear WS, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Cooperative assembly of higher-order Notch complexes functions as a switch to induce transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611092104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rock R, Heinrich AC, Schumacher N, Gessler M. Fjx1: a notch-inducible secreted ligand with specific binding sites in developing mouse embryos and adult brain. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:602–12. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maier MM, Gessler M. Comparative analysis of the human and mouse Hey1 promoter: Hey genes are new Notch target genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:652–60. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedmann DR, Kovall RA. Thermodynamic and structural insights into CSLDNA complexes. Protein Sci. 2010;19:34–46. doi: 10.1002/pro.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam Y, Weng AP, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural requirements for assembly of the CSL.intracellular Notch1.Mastermind-like 1 transcriptional activation complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21232–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Mutational and energetic studies of Notch 1 transcription complexes. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinmann E, Geimer Le Lay AS, Sellars M, Kastner P, Chan S. Ikaros represses the transcriptional response to Notch signaling in T-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7465–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00715-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, et al. Notch dimerization is required for leukemogenesis and T cell development. Genes & Development. 2010 doi: 10.1101/gad.1975210. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728–33. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC5 dictionary: organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2184–95. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng AP, et al. Growth suppression of pre-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by inhibition of notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:655–64. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.655-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malecki MJ, et al. Leukemia-associated mutations within the NOTCH1 heterodimerization domain fall into at least two distinct mechanistic classes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4642–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01655-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.