Abstract

Surface functionalization of semiconductors has been the backbone of the newest developments in microelectronics, energy conversion, sensing device design, and many other fields of science and technology. Over a decade ago, the notion of viewing the surface itself as a chemical reagent in surface reactions was introduced, and adding a variety of new functionalities to the semiconductor surface has become a target of research for many groups. The electronic effects on the substrate have been considered as an important consequence of chemical modification. In this work, we shift the focus to the electronic properties of the functional groups attached to the surface and their role on subsequent reactivity. We investigate surface functionalization of clean Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1 surfaces with amines as a way to modify their reactivity and to fine tune this reactivity by considering the basicity of the attached functionality. The reactivity of silicon and germanium surfaces modified with ethylamine (CH3CH2NH2) and aniline (C6H5NH2) is predicted using density functional theory calculations of proton attachment to the nitrogen of the adsorbed amine to differ with respect to a nucleophilic attack of the surface species. These predictions are then tested using a model metalorganic reagent, tetrakis(dimethylamido)titanium (((CH3)2N)4Ti, TDMAT), which undergoes a transamination reaction with sufficiently nucleophilic amines, and the reactivity tests confirm trends consistent with predicted basicities. The identity of the underlying semiconductor surface has a profound effect on the outcome of this reaction, and results comparing silicon and germanium are discussed.

Keywords: adsorption, organic, nucleophile, spectroscopy

The recent boom in the development of microelectronics, energy conversion, and sensing devices is tied very closely to our ability to selectively modify well-defined surfaces by chemical means. The opportunities offered by the passivation and functionalization of semiconductor surfaces have already led to the concepts of ultrathin films and molecular-size features in devices being used for practical applications (1). Further development of the field will require that our understanding of the chemical processes on semiconductor surfaces reach a truly molecular level. Surface functionalization can affect either the electronic properties or the chemical reactivity of the semiconductor (2–4). For example, similarly to high-spatial-resolution doping, functionalizing selected areas of a semiconductor surface with predesigned molecules affects the electronic state of the semiconductor (5). Surface chemistry may bring new states into the midgap region of the material as well as affect the positions of HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) (6), a degree of control that is especially important in surface functionalization of semiconductor nanostructures, where electronic properties can be affected tremendously by the functional group present on the surface (3). In other cases, modification of semiconductor surfaces is aimed at providing a chemical “hook” for further surface functionalization, without explicit regard to the electronic properties of the functional groups that are placed on the surface (7–9). Hence the functional groups, such as ─OH, ─COOH, and ─NH2, attached to the surface are normally thought of as a starting point for further processing rather than interesting entities whose electronic properties are affected by the surface being functionalized. Granted, for potential applications in molecular electronics, the electronic properties of a molecule are the major force behind the development of this field, but in that case the aim is often to decouple these properties from the behavior of the solid substrate.

In the race for faster, cheaper, more reliable methods of semiconductor surface functionalization, much recent effort has focused on exploring new functionalities rather than on understanding and finely tuning the effects of a single one. The ability to add new functionalities to semiconductor surfaces builds upon two decades of research in which the concept of the surface as a chemical reagent in semiconductor surface chemistry has been shown to be a powerful construct (7–15). Specifically, surfaces of group IV elemental semiconductors are viewed as a collection of specific sites with different electrophilic or nucleophilic properties. On well-understood Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1 surfaces, the mechanisms of reactions are commonly analyzed and predicted by following the charge distribution within the surface dimers of the 2 × 1 reconstructions. The mechanisms of most of the addition processes are often described in these terms. For example, in a Diels–Alder reaction with butadiene, the dimers at the Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1 surfaces were considered the dienophile (16–18) and other pericyclic reactions on both clean Si and Ge surfaces are described in a similar manner (19–21).

In the current work, we extend this idea of describing the reactive surface moieties through their defined electrophilic or nucleophilic properties to the adsorbate species themselves. By taking the same approach for functionalized surfaces, we add to our ability to fine tune many chemical processes by selecting similar functionalities that exhibit different reactivities. Specifically, we explore the ability to control the electronic properties of adsorbates on semiconductor surfaces by varying both the adsorbate and the surface. The results are evaluated in the context of the Lewis basicity of the functionalized surface. Although the concepts of basicity and acidity are so well suited to describe the extent of reactivity in homogeneous processes and are indeed characteristics of the electronic properties of the functional groups, they are rarely applied to describe the behavior of adsorbates at semiconductor surfaces. The approach itself in general is not entirely new and has been previously applied to understand the reactivity of selected surface reactive sites on metallic surfaces in heterogeneous catalysis (22, 23), but quantitative application of this concept to surface reactions is a difficult task. Nevertheless, with the help of computational investigation, we can predict the reactivity of such modified surfaces by following the affinity of the functional groups to protons, which correlates with the basicity, and then test some of these predictions experimentally.

This paper will use the well-understood reactions of amines on group IV semiconductor surfaces to explore the validity of such an approach. We will start with modification of Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1 surfaces with primary amines that have different electronic properties, including ethylamine (CH3CH2NH2) with an electron donating ethyl group, and aniline (C6H5NH2) with electron withdrawing phenyl ring, and predict the reactivities of the surfaces functionalized with these amines in a test reaction where the functionalized surface acts as a nucleophile. We will then show experimentally that the surface basicity can indeed be varied, consistent with concepts from homogeneous chemistry, leading to the ability to control subsequent reaction on the functionalized surface.

Results and Discussion

To study the tunability of the reactivity of adsorbates on semiconductor surfaces, two model amines were chosen for investigation—ethylamine and aniline. They have very different basicities, with pKb(ethylamine) = 4.8 and pKb(aniline) = 9.7 (pKb is defined as - log 10Kb, where Kb is a base dissociation constant; Kb = [HB+] × [OH-]/[B] for a reaction B + H2O↔HB+ + OH-), and hence are expected to exhibit different reactivities to incoming electrophiles following their attachment to a clean semiconductor surface. The same conclusion can be reached by applying a more rigorous perspective, the gas-phase basicity (or intrinsic basicity), which considers the energy produced upon protonation of gas-phase, solution-free molecules (24). Although the basicity of the surface species produced by the dissociation of these amines on a semiconductor surface is expected to differ from that of the molecular precursors and the basicity itself is difficult to quantify for surface species, the trend in reactivity is expected to follow the trend in reactivity of the starting amines, ethylamine and aniline, in this study.

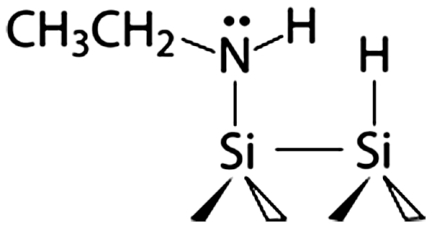

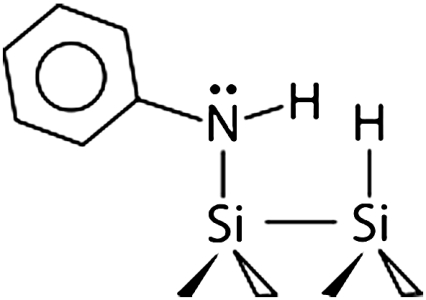

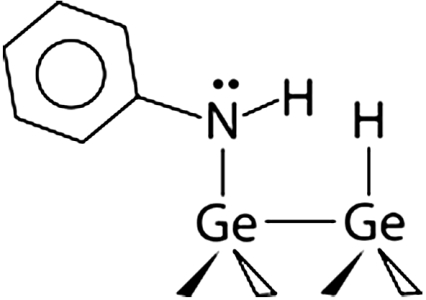

Surfaces precovered by the amine functional groups were produced by dissociating these molecules on clean Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1 surfaces. Both alkyl and aromatic amines have been thoroughly studied by several research groups and shown to adsorb via N─H dissociation at room temperature on Si(100)-2 × 1 (25–34). Although the long-range arrangement of the produced surface species remains to be understood, their chemical identity is known, as shown in Scheme 1. Ethylamine is expected to dissociate into surface-bound CH3CH2NH─ and H─ species and aniline should produce C6H5NH─ and H─ functionalities. As expected, in our studies a Si(100)-2 × 1 crystal exposed to saturation doses of ethylamine or aniline shows infrared absorptions corresponding to the Si─H, C─H, and N─H characteristic stretching vibrations consistent with the previous studies. The results presented by blue lines in Fig. 1 collected by multiple internal reflection Fourier transform infrared (MIR-FTIR) spectroscopy illustrate the representative spectral regions characteristic of amine dissociation at a full coverage for both ethylamine and aniline.

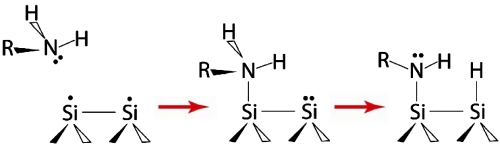

Scheme 1.

Reaction of a primary amine on a clean Si(100)-2 × 1 surface.

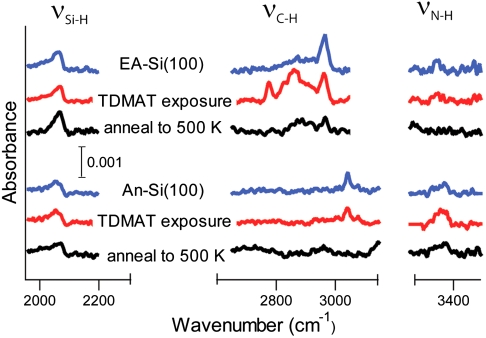

Fig. 1.

Representative spectral regions in the MIR-FTIR studies of full coverage of ethylamine (EA) and aniline (An) (blue lines) on the Si(100)-2 × 1 surface, these same surfaces exposed to a saturating dose of TDMAT (red lines), and then heated to 500 k (black lines).

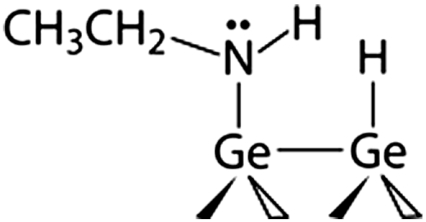

The products of adsorption of an amine on Ge(100)-2 × 1 may differ from that on Si(100)-2 × 1. On Ge(100)-2 × 1, whereas some amines undergo N─H dissociative adsorption at room temperature, others remain trapped in the dative bonded state under the same conditions (29, 32). To determine whether aniline adsorbs on Ge(100)-2 × 1 dissociatively or molecularly, that adsorption was studied using both MIR-FTIR spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Fig. 2 shows infrared absorption spectra of a saturation coverage of aniline at room temperature and a multilayer of aniline formed by low temperature physisorption on Ge(100)-2 × 1. A calculated spectrum for the N─H dissociated adduct is also shown for comparison. The analysis of the infrared spectra for aniline/Ge(100) indicates that aniline adsorbs on Ge(100)-2 × 1 via N─H dissociation at room temperature. First, one of the primary features gained upon adsorption of aniline is the peak at 1,977 cm-1, corresponding to a Ge─H stretch. The appearance of this mode implies that hydrogen has transferred from the molecule to the surface, indicating that N─H and/or C─H dissociation has occurred. Second, the chemisorbed spectrum (Fig. 2B) lacks the NH2 scissoring mode at 1,620 cm-1 in the aniline multilayer, thus supporting N─H dissociation. Further support for N─H dissociation is provided by the excellent match between the chemisorbed spectrum (Fig. 2B) and the vibrational spectrum (Fig. 2C) calculated for the N─H dissociated adduct. DFT normal mode analysis indicates that the peaks at 1,246 and 1,362 cm-1 in the chemisorbed spectrum are specific to an N─H dissociated adduct. C─H dissociation can be ruled out by the retention of peaks associated with these bonds, as well as by separate infrared studies of aniline-d5 that show the presence of Ge─H and not Ge─D.

Fig. 2.

(A) IR spectrum (intensity scaled by a factor of 0.004) of an aniline multilayer on Ge(100) at 130 K. (B) An average of IR spectra taken following saturation exposure of aniline to Ge(100)-2 × 1 at 300 K. (C) IR spectrum calculated for intradimer N─H dissociated aniline on a two-dimer Ge23H24 cluster. Calculated frequencies are scaled by 0.96.

Fig. 3 shows the Ge(3d), N(1s) and C(1s) XP spectra taken after saturation exposure of aniline on Ge(100)-2 × 1 at room temperature. The N(1s) spectrum shows the core-level peak is fit to only one component centered at 397.8 eV. This suggests that only one chemically distinct type of nitrogen is present at the surface, with the N(1s) binding energy consistent with nitrogen covalently bonded to the germanium surface according to the literature (29). The two peaks centered at 285.0 and 283.8 eV visible in the C(1s) XPS spectrum of aniline/Ge(100)-2 × 1 at room temperature correspond to carbon bonded and not bonded to the relatively more electronegative nitrogen atom within the adsorbate, respectively, with the peak area ratio (3∶1) the same that was reported in the room-temperature study of aniline/Si(100)-2 × 1 (28) for which N─H dissociation was also observed. An analysis of the C(1s) peak area normalized to the area of the bulk Ge 3d 5/2 peak yields a total saturation coverage of 0.35, i.e., approximately 1 aniline molecule per 3 Ge surface atoms. Because each adsorbed aniline molecule bonds to two Ge atoms after dissociative adsorption, saturation corresponds to 70% of the Ge surface atoms covered. The XPS spectra also indicate that the Ge surface remains unoxidized during the adsorption experiments. The Ge(3d) spectrum shows a single peak associated with bulk Ge, and no feature in the Ge(3d) spectrum from oxidized germanium can be observed. Although detection of small amounts of oxidation using the Ge(3d) peak is difficult in our system, an O(2p) scan confirms the absence of germanium oxide after adsorption of aniline.

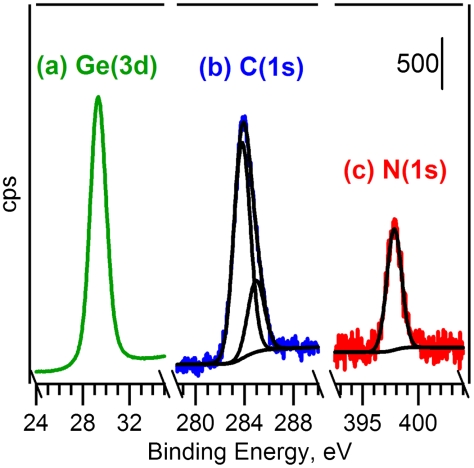

Fig. 3.

(A) Ge(3d), (B) C(1s) and (C) N(1s) photoelectron spectra taken after 260 L saturation exposure of aniline to Ge(100)-2 × 1 at room temperature. The Ge(3d) spectrum has been scaled by 1/15.

Thus we have confirmed the amine dissociation on Si(100)-2 × 1 and Ge(100)-2 × 1. For each system, the reaction generates a surface-bound secondary amine as shown in Scheme 1. This amine is itself characterized by a reactivity toward subsequent nucleophilic/electrophilic reactions, which is affected by both the R group (ethyl versus phenyl) and the surface (Si versus Ge).

Although at room temperature the reactivity of both primary amine reactants is sufficient to dissociate an N─H group, it is expected that the reactivities of the secondary surface-bound amine groups produced during this process may differ depending on the R group and the surface itself. Here we use a reaction with a metalorganic compound, tetrakis(dimethyldamido)titanium (TDMAT), as a model system to test the reactivity of the surfaces precovered with amines. TDMAT is known to undergo a transamination reaction with the amine-terminated surface (35) produced by adsorption of ammonia on Si(100)-2 × 1 (36), as illustrated in Scheme 2. This process has been well studied because the transamination reaction can be used as an initial step in thin film growth targeting diffusion barrier films such as TiCN (35, 37–39). The transamination reaction is known to follow the nucleophilic attack of the lone electron pair of a nitrogen atom of the surface functionality onto a metal center of the metal-organic precursor. Hence it serves as an excellent test-bed for probing the basicity of the adsorbed amine.

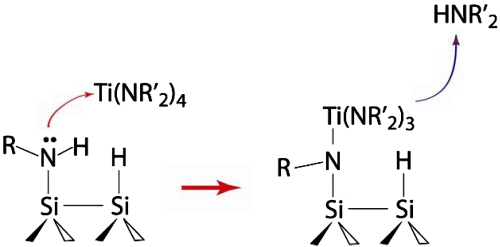

Scheme 2.

Reaction of transamination used to test the reactivity of amine-precovered semiconductor surfaces.

To characterize the basicity of the adsorbed amine functionalities, we first carried out a computational study to determine reaction energetics that are correlated with basicity. Because the pKb values are not easily determined computationally for this type of surface and also because they may not directly predict the reactivity of surface species in heterogeneous surface chemistry, we consider instead a process that is in essence identical to that employed for calculating the intrinsic basicity of the gas-phase molecules. We evaluate the ability of the surface-bound secondary amine groups to accept a proton as a measure of the basicity of the surface species. Table 1 summarizes the results of this computational investigation. These calculated energies allow us to understand in general terms the relative reactivity of the four species studied (ethylamine/Si, aniline/Si, ethylamine/Ge, aniline/Ge) toward nucleophilic attack of an electrophile.

Table 1.

Thermodynamics of protonation reaction

| Species | E(A + H+) (vs. aniline/Si(100)), kJ/mol |

Ethylamine/Si(100)

|

−27.5 |

Aniline/Si(100)

|

−0.0 |

Ethylamine/Ge(100)

|

−68.9 |

Aniline/Ge(100)

|

−40.5 |

Analysis of the thermodynamics of the protonation reaction for amine species on Si(100) and Ge(100) performed by a computational analysis using B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) method as an illustration of surface reactivity in a transamination reaction. The thermodynamic change in kJ/mol is given with respect to the gas-phase protonation of the aniline-covered Si(100) represented by the Si9H12 cluster. The absolute value obtained computationally for this species is -959.8 kJ/mol.

Although the analysis of the protonation process in secondary amines provides only a partial view of their reactivity in a nucleophilic attack, the data in Table 1 predict that this reactivity will be substantially different for ethylamine compared to aniline dissociated on Si(100)-2 × 1 or Ge(100)-2 × 1, and also that the nature of the surface may influence the reactivity dramatically. For both surfaces, the attachment of a proton on the secondary amine is much more exoenergetic for ethylamine than for aniline. This result correlates well with the pKb values for ethylamine and aniline and is expected based on the electron donating and withdrawing character of the alkyl and phenyl groups, respectively. Moreover, the energies of proton attachment are more favorable on Ge for both amines than they are on Si. Thermodynamically, then, nucleophilic attack of the lone pair of a nitrogen atom onto a target molecule should be less favorable for aniline-exposed silicon than for ethylamine-covered Si(100)-2 × 1, and at the same time the energetic propensity of the aniline-exposed Ge(100)-2 × 1 surface toward the same proton attachment reaction is even higher than that of ethylamine-covered Si(100)-2 × 1. Thus, if nucleophilic attack is the rate-determining step in a reaction, the more basic the amine, the more facile the reaction with an electrophile is expected to be. A simple protonation analysis provides a convenient and relatively easy-to-predict computational handle for estimating the basicity of a surface-bound amine group, with energetics of this process expected to parallel the relative kinetic barriers for the test reactions.

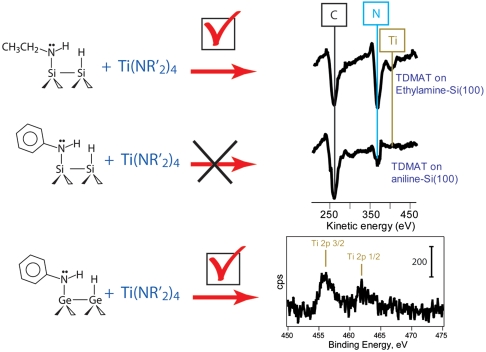

In order to test this hypothesis, we investigated the reactivities of ethylamine- and aniline-exposed Si(100)-2 × 1 and compared them to that of aniline-covered Ge(100)-2 × 1 in the transamination reaction with a TDMAT molecule. This reaction has been previously shown to occur on ammonia-exposed Si(100)-2 × 1 and the full mechanism was presented for this process previously (35). It is important to use a test reaction that is insensitive with respect to possible unoccupied surface sites or defects, and TDMAT provides this opportunity because of the large size of this metalorganic molecule. Despite its size, the transamination process with TDMAT was shown to proceed selectively for ammonia-exposed Si(100)-2 × 1, replacing only a single dimethylamino-group of TDMAT with surface species, as schematically shown in Scheme 2 (35). The results of the current study show that this test reaction easily occurs on ethylamine-covered Si(100)-2 × 1 and does not occur on aniline-exposed silicon as confirmed by the MIR-FTIR spectroscopy studies presented in Fig. 1 by the red lines. Representative vibrational features corresponding to the TDMAT reaction product are clearly observed for the ethylamine-covered surface and are absent for the aniline-covered surface. Fig. 4 presents the corresponding Auger electron spectroscopy studies consistent with this conclusion. Clearly, an elemental composition consistent with TDMAT reaction at the ethylamine-covered surface, including the presence of a titanium signal and a large increase in the N signal, is evident in the AES spectra collected for the TDMAT exposed to the ethylamine-covered Si(100)-2 × 1 whereas titanium is clearly absent following the reaction of TDMAT on aniline-exposed Si(100)-2 × 1. The surface species produced in this reaction are stable as confirmed by the results of annealing the surface produced by TDMAT exposure to 500 K, shown in black lines in Fig. 1, confirming the transamination reaction as opposed to the presence of weakly adsorbed species following TDMAT reaction on ethylamine-covered Si(100).

Fig. 4.

A summary of AES studies of transamination reaction for TDMAT on ethylamine- and aniline-precovered Si(100)-2 × 1 and of XPS investigation of the same reaction on aniline-precovered Ge(100)-2 × 1.

To test the effect of the surface on the basicity of the surface-bound amine moiety and its corresponding reactivity toward the transamination reaction, aniline-covered Ge(100)-2 × 1 was investigated. According to Table 1, this secondary amine is predicted thermodynamically to exhibit reactivity even more favorable than that of the ethylamine-covered Si(100) surface. Based on the XPS studies we can conclude that a reaction with TDMAT does occur with aniline attached to the Ge(100)-2 × 1 surface at room temperature. The XPS data over the Ti 2p core-level region given in Fig. 4 show clear presence of titanium. Although the complexity of the spectrum suggests that following the transamination process, further reactions may take place on Ge(100) at room temperature, the result supports the prediction that the transamination step occurs on aniline-precovered Ge(100) but not on aniline-precovered Si(100).

The results show that the basicity of the surface-attached amine group, as paralleled with the proton affinity and measured through the transamination reaction with TDMAT, can be tuned by choice of amine adsorbate and by selection of the semiconductor substrate. Control over the adsorbate basicity, using concepts from homogeneous chemistry, leads to the ability to control subsequent reaction on the functionalized surface. This scheme provides another way of controlling reactions at semiconductor surfaces important for ultimate applications in a variety of electronic and optoelectronic devices. Because only a partial view of the complex surface chemistry was used as an indicator of surface reactivity here, additional studies will be required to decouple steric and electronic effects on the reaction, to understand the effects of surface coverage, and to investigate the complexity of the reactions following the initial steps on the surface. However, these results clearly show that the reactivity in nucleophilic reactions is affected by the nature of the surface species participating in the reaction as a nucleophile and also by the nature of the solid surface itself.

Materials and Methods

The experimental and computational investigations presented in this manuscript were conducted in two research laboratories. Infrared and Auger electron spectroscopy investigations of silicon surfaces, as well as the computational description of all the surface species except aniline/Ge(100)-2 × 1, were performed at the University of Delaware. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and vibrational spectroscopy investigation of germanium surfaces were conducted at Stanford University.

At the University of Delaware, the experiments were done in an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) chamber (base pressure of approximately 5 × 10-10 torr) set up to perform infrared spectroscopy measurements in a multiple internal reflection mode using a Nicolet Magna 560 spectrometer with an external MCT detector. Each spectrum was collected at room temperature and compared to the background corresponding to the clean Si(100) surface. Spectra were averaged over 2,048 scans with a resolution of 4 cm-1. This instrument was also equipped with a mass spectrometer and an Auger electron spectrometer, which were used to confirm the purity of the compounds used and the cleanliness of the silicon surface, respectively. The silicon sample [25 × 20 × 1 mm trapezoidal Si(100) crystal polished on both sides, with 45° beveled edges (Harrick Scientific)] was mounted on a manipulator capable of heating it to 1,150 K using an e-beam heater (McAllister Technical Services) and cooling it with liquid nitrogen. The silicon surface before every experiment was prepared by argon (Mathesson, 99.999%) sputtering, followed by annealing to temperatures of 1,100 K. These sputtering-annealing cycles were performed until the Auger spectrum of a clean silicon surface was obtained.

At Stanford, infrared spectroscopy experiments were completed in a previously described UHV chamber (31) paired with a BioRad FTS-60A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer equipped with an MCT detector. A trapezoidally shaped Ge(100) crystal (19 × 14 × 1 mm, 45° beveled edges) designed for multiple internal reflection (MIR) experiments was conductively heated by a resistive tungsten heater and cooled by heat exchange with a copper braid connected to a liquid nitrogen reservoir. Ge(100) surface cleaning via two cycles consisted of sputtering at room temperature followed by annealing to 900 K. XPS studies were performed in a separate UHV chamber, which has also been described previously (40). Due to interference by the Ge Auger series, the C(1s) photoelectron spectra were recorded with the Al anode and the N(1s) spectra with the Mg anode, where anode power is 250 W (12.5 kV anode voltage, 20 ma emission current.) Spectra were collected with a pass energy of 25 eV, and the Ge(3d) photoelectron peak was used as an internal standard for calibration of the energy scale and peak intensity.

In all experiments, ethylamine and aniline (Aldrich, research purity) and TDMAT (Epichem, 99.99%) were cleaned by several freeze-pump-thaw cycles before introduction into the UHV chamber. Purity of the compounds was confirmed in situ by mass spectrometry. Doses of the compounds are expressed in Langmuirs (1 Langmuir = 1L = 10-6 torr· sec). Density functional calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level of theory (41, 42). A Si9H12 cluster model, representing one silicon surface dimer, was used to simulate the Si(100)-2 × 1 surface. An analogous Ge9H12 cluster model was used to represent the Ge(100)-2 × 1 surface. Predicted vibrational frequencies of optimized structures were calculated and compared to experimental spectroscopic features, using a correction factor of 0.96. Calculations were performed using the GAUSSIAN 03 suite of programs (43).

Acknowledgments.

S.F.B. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) (Grant CHE 0910717). A.V.T. acknowledges support from NSF (Grant CHE 0650123) and from the donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Yaffe O, et al. Molecular electronics at metal/semiconductor junctions. Si inversion by sub-nanometer molecular films. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2390–2394. doi: 10.1021/nl900953z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanrath T, Korgel BA. Chemical surface passivation of Ge nanowires. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15466–15472. doi: 10.1021/ja0465808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashouti MY, Tung RT, Haick H. Tuning the electrical properties of Si nanowire field-effect transistors by molecular engineering. Small. 2009;5:2761–2769. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasudevan S, et al. Controlling transistor threshold voltages using molecular dipoles. J Appl Phys. 2009;105:093703. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avouris P. Manipulation of matter at the atomic and molecular levels. Acc Chem Res. 1995;28:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamers RJ. Formation and characterization of organic monolayers on semiconductor surfaces. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2008;1:707–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bent SF. Organic functionalization of group IV semiconductor surfaces. Principles, examples, applications, and prospects. Surf Sci. 2002;500:879–903. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loscutoff PW, Bent SF. Reactivity of the germanium surface: Chemical passivation and functionalization. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2006;57:467–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leftwich TR, Teplyakov AV. Chemical manipulation of multifunctional hydrocarbons on silicon surfaces. Surf Sci Rep. 2008;63:1–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buriak JM. Organometallic chemistry on silicon and germanium surfaces. Chem Rev. 2002;102(5):1271–1308. doi: 10.1021/cr000064s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filler MA, Bent SF. The surface as molecular reagent: Organic chemistry at the semiconductor interface. Prog Surf Sci. 2003;73:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamers RJ, et al. Cycloaddition chemistry of organic molecules with semiconductor surfaces. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:617–624. doi: 10.1021/ar970281o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu X, Lin MC. Reactions of some [C, N, O]-containing molecules with Si surfaces: Experimental and theoretical studies. Int Rev Phys Chem. 2002;21:137–184. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao F, Xu GQ. Attachment chemistry of organic molecules on Si(111)-7 × 7. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:882–893. doi: 10.1021/ar0400488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciampi S, Harper JB, Gooding JJ. Wet chemical routes to the assembly of organic monolayers on silicon surfaces via the formation of Si─C bonds: surface preparation, passivation and functionalization. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:2158–2183. doi: 10.1039/b923890p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teplyakov AV, Kong MJ, Bent SF. Vibrational spectroscopic studies of Diels-Alder reactions with the Si(100)-2 × 1 surface as a dienophile. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11100–11101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teplyakov AV, Kong MJ, Bent SF. Diels-Alder reactions of butadienes with the Si(100)-2 × 1 surface as a dienophile: Vibrational spectroscopy, thermal desorption and near edge X-ray absorption fine structure studies. J Chem Phys. 1998;108:4599–4606. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teplyakov AV, Lal P, Noah YA, Bent SF. Evidence for a Retro-Diels-Alder reaction on a single crystal surface: Butadienes on Ge(100) J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7377–7378. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bocharov S, Dmytrenko O, Méndez De Leo LP, Teplyakov AV. Azide reactions for controlling clean silicon surface chemistry: Benzylazide on Si(100)-2 × 1. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9300–9301. doi: 10.1021/ja0623663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Méndez De Leo LP, Teplyakov AV. Nitro group as a means of attaching organic molecules to silicon: Nitrobenzene on Si(100)-2 × 1. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:6899–6905. doi: 10.1021/jp057415x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leftwich TR, Teplyakov AV. Cycloaddition reactions of phenylazide and benzylazide on a Si(100)-2 × 1 surface. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:4297–4303. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu XY, Madix RJ, Friend CM. Unraveling molecular transformations on surfaces: a critical comparison of oxidation reactions on coinage metals. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:2243–2261. doi: 10.1039/b800309m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong JL, Mullins CB. Surface science investigations of oxidative chemistry on gold. Accounts Chem Res. 2009;42:1063–1073. doi: 10.1021/ar8002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter EPL, Lias SG. Evaluated gas phase basicities and proton affinities of molecules: An update. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1998;27:413–656. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugler T, Ziegler C, Gopel W. Characterization and simulation of organic adsorbates on the Si(100)(2 × 1)-surface using photoelectron spectroscopy and quantum mechanical calculations. Mater Sci Eng B. 1996;37:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bitzer T, Alkunshalie T, Richardson NV. An HREELS investigation of the adsorption of benzoic acid and aniline on Si(100)-2 × 1. Surf Sci. 1996;368:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rummel RM, Ziegler C. Room temperature adsorption of aniline (C6H5NH2) on Si(100)(2 × 1) observed with scanning tunneling microscopy. Surf Sci. 1998;418:303–313. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao X, et al. Bonding of nitrogen-containing organic molecules to the silicon(001) surface: The role of aromaticity. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:3759–3768. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim A, Filler MA, Kim S, Bent SF. Ethylenediamine on Ge(100)-2 × 1: The role of interdimer interactions. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:19817–19822. doi: 10.1021/jp054340o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mui C, Wang GT, Bent SF, Musgrave CB. Reactions of methylamines at the Si(100)-2 × 1 surface. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:10170–10180. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mui C, Han JH, Wang GT, Musgrave CB, Bent SF. Proton transfer reactions on semiconductor surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4027–4038. doi: 10.1021/ja0171512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang GT, et al. Reactions of cyclic aliphatic and aromatic amines on Ge(100)-2 × 1 and Si(100)-2 × 1. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:4982–4996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widjaja Y, Musgrave CB. A density functional theory study of the nonlocal effects of NH3 adsorption and dissociation on Si(100)-2 × 1. Surf Sci. 2000;469:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widjaja Y, Mysinger MM, Musgrave CB. Ab initio study of adsorption and decomposition of NH3 on Si(100)-2 × 1. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:2527–2533. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Reyes JCF, Teplyakov AV. Surface transamination reaction for tetrakis(dimethylamido)titanium with NHX-terminated Si(100) surfaces. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:16498–16505. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez-Reyes JCF, Teplyakov AV. Cooperative nitrogen insertion processes: Thermal transformation of NH3 on a Si(100) surface. Phys Rev B. 2007;76:075348-075348-16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodríguez-Reyes JCF, Teplyakov AV. Mechanisms of adsorption and decomposition of metal alkylamide precursors for ultrathin film growth. J Appl Phys. 2008;104:084907-084907-6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez-Reyes JCF, Teplyakov AV. Chemistry of diffusion barrier film formation: Adsorption and dissociation of tetrakis-(dimethylamino)-titanium on Si(100)-2 × 1. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:4800–4808. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodríguez-Reyes JCF, Ni C, Bui HP, Beebe TP, Jr, Teplyakov AV. Reversible tuning of the surface chemical reactivity of titanium nitride and nitride-carbide diffusion barrier thin films. Chem Mater. 2009;21:5163–5169. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filler MA, Van Deventer JA, Keung AJ, Bent SF. Carboxylic acid chemistry at the Ge(100)-2 × 1 interface: Bidentate bridging structure formation on a semiconductor surface. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:770–779. doi: 10.1021/ja0549502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becke AD. A new mixing of Hartree–Fock and local density-functional theories. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron-density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian, Inc. Pittsburgh: Gaussian, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]