Abstract

Cdc42 is a member of the Rho GTPase family of intracellular molecular switches regulating multiple signaling pathways involved in actomyosin organization and cell proliferation. Knowledge of its signaling function in mammalian cells came mostly from studies using the dominant-negative or constitutively active mutant overexpression approach in the past 2 decades. Such an approach imposes a number of experimental limitations related to specificity, dosage, and/or clonal variability. Recent studies by conditional gene targeting of cdc42 in mice have revealed its tissue- and cell type-specific role and provide definitive information of the physiological signaling functions of Cdc42 in vivo.

Keywords: Cdc42, Cellular Regulation, Mouse Genetics, Rho, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Rho family GTPases belong to the Ras GTPase superfamily and act as binary molecular switches that are turned on in the GTP-bound state and turned off in the GDP-bound state in response to a variety of stimuli, including soluble factors such as growth factors and cytokines and cell-cell or integrin-extracellular matrix interactions (Fig. 1) (1, 2). They are well recognized signal mediators of a wide variety of pathways in eukaryotic cells (3–5). As a member of the Rho GTPase family, the cell division cycle protein Cdc42 was first discovered as an essential gene product in Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in actin cytoskeletal architecture (6), and its human homolog was shown to be highly conserved, suggesting that Cdc42 may play fundamental roles in mammalian cell biology. Subsequent genetic studies in yeast discovered a crucial function for Cdc42 in the establishment of cell polarity, particularly as it pertains to the assembly of bud emergence in yeast (7, 8). In Caenorhabditis elegans, depletion of Cdc42 results in polarity defects and mislocalization of Par (partitioning-defective) polarity proteins (PAR6, PAR3, and PAR2) (9, 10), indicating that Cdc42 is required for both establishing and maintaining cell polarity in the early embryo. Furthermore, expression of dominant-negative and constitutively active mutants of Cdc42 in Drosophila has also provided important insights into its involvement in polarity establishment and morphogenesis (11, 12).

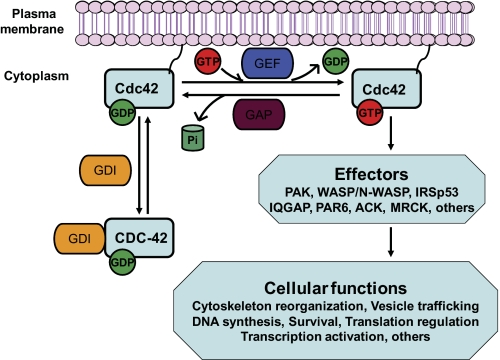

FIGURE 1.

Conventional view of the signaling function and regulation of Cdc42. Cdc42 cycles between the GDP-bound inactive state and the GTP-bound active state. The GTP binding and GTP hydrolysis cycle is tightly regulated at specific intracellular locations by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Upon activation by various stimuli, activated Cdc42 can transiently interact with multiple effector proteins to transduce signals that impact on cell functions, including cytoskeleton organization, vesicle trafficking, cell cycle progression, survival, translation, and transcription.

Early studies carried out in various mammalian cell lines by overexpressing dominant-negative and/or constitutively active mutants have shown that Cdc42 can have an important role in cytoskeleton organization, transcription, cell cycle progression, vesicle trafficking, survival, and other cell functions (Fig. 1) (1, 8, 13). Lagging behind the genetic studies in lower eukaryotes, genetic information of Cdc42 in mammalian systems was limited until recently in part due to an early embryonic lethality phenotype upon cdc42 gene deletion in mouse embryos. In this minireview, we discuss recent mouse genetic studies of Cdc42 utilizing conditional tissue-specific targeting strategies in cells, including heart, pancreas, nervous system, blood, bone, eye, immune system, and skin. These physiological characterizations of the tissue- and cell type-specific signaling function of Cdc42 revitalize an “old” field of cell signaling.

Signaling Function of Mammalian Cdc42 in Vitro

Extensive biochemical studies have been carried out in pursuing the role of Cdc42 in diverse cell responses and signaling pathways. The use of dominant-negative or constitutively active mutants of Cdc42 generated by single amino acid substitutions has been especially helpful in assigning its potential involvement in multiple signaling cascades in cell regulation (14–16). These have been extensively elaborated by several excellent reviews (17–21) and will not be the focus of this discussion. For example, Cdc42 has been implicated as a key regulator of actin filopodial induction and migration through the use of T17N dominant-negative mutant overexpression in fibroblasts and several other cell types. This cell function was also demonstrated in Cdc42−/− primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (22). Cells expressing the T17N mutant or loss of cdc42 were defective in adhesion, wound healing, polarity establishment, and migration, and these cell phenotypes are associated with deficiencies in PAK1 (p21-activated kinase 1), GSK-3β (glycogen synthase kinase-3β), myosin light chain (MLC),3 and focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. Another well recognized cell function of Cdc42 involves the interaction between Cdc42-GTP and the Par6-Par3-atypical PKC (aPKC) complex important for the establishment of epithelial polarity during directed cell migration and morphogenesis (23–25). The establishment of apical-basal polarity within a single cell and throughout growing tissue is a key feature of epithelial morphogenesis. Depletion of Cdc42 does not prevent the establishment of apical-basal polarity in individual cells but disrupts spindle orientation during cell division (26).

Although the conventional cell biological approach has led to proposals of many functions of Cdc42, it does have limitations given the signaling cross-talk between different Rho GTPases and the potential nonspecific nature of the mutants. The dominant-negative mutant of Cdc42 works by sequestering the upstream Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), but there are more than 70 GEFs in the mammalian genome, many of which are known to regulate multiple Rho GTPases (17, 27). Thus, overexpression of a dominant-negative mutant can block endogenous Cdc42 activity while impacting on multiple GEF functions and affecting the activities of multiple Rho GTPases (28, 29). Conversely, the constitutively active Cdc42 mutant can activate a number of shared effectors with Rac or other GTPases (e.g. the Cdc42/Rac-interactive binding domain-containing molecules and IQGAPs) and may not allow a dynamic activation/dissociation of the downstream effectors to execute their normal functions. Another potential experimental limitation of conventional studies is the wide usage of clonal cell lines. One study in clonal fibroblastoid cells generated by differentiation and immortalization of Cdc42-null embryonic stem cells found normal formation of filopodia and normal cell migration, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis (30), whereas another study using early passage Cdc42−/− primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts found Cdc42 to be essential for filopodial induction, directional migration, and proliferation. These studies suggest that it is possible that immortalization and/or clonal variability may impact on cell phenotypes, as Cdc42-related Rho GTPases such as Rac1, Wrch-2, and TC10 could play a redundant role required for similar functions (22). Therefore, although conventional cell biological studies have provided an excellent framework of possible functions and signaling pathways regulated by Cdc42, how each signaling function suggested by such studies would manifest in specific tissue cell types needs to be verified or repudiated to put the suggested biochemical mechanisms in a proper physiological context.

Signaling Functions of Mammalian Cdc42 in Vivo

Given the above considerations of the conventional biochemical and cell biological approaches, tissue-specific mouse gene targeting clearly represents an improved strategy in determining the functions of Cdc42 in vivo. Recent studies employing the Cre/loxP mouse conditional knock-out methodology have revealed a number of physiologically relevant, sometimes unexpected, functions of Cdc42 in a tissue/organ-specific manner (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of tissue-specific gene targeting studies of Cdc42 signaling function in mice

SC, Schwann cell.

| Gene-targeting driver | Phenotypes and pathways |

|---|---|

| Heart | |

| Cardiac-specific α-MHC-Cre | Heart-specific deletion of Cdc42 enhances cardiac growth response and renders JNK1/2 inactive along with an increase in NFAT activity (37). |

| Nervous system | |

| Emx1-Cre, hGFAP-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 in neural progenitors results in apical-basal polarity defects mediated through altered location of the Par complex and lost adherens junctions (47). |

| Foxg1-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 in mouse telencephalon leads to Shh-independent holoprosencephaly associated with a loss of neural epithelium polarity (48). |

| Wnt-1-Cre | Ablation of Cdc42 in neural crest stem cells shows defects in maintenance, migration, and differentiation of these cells through attenuated EGF signaling (49). |

| Nestin-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 in neural progenitors causes defects in formation of axon tracts along with an increased inactivation of cofilin (50). |

| Dhh-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 in SCs alters axon sorting through impaired proliferation and delayed differentiation of SCs. Cdc42 is downstream of and activated by NRG1, a known SC mitogen (54). |

| Liver | |

| Alb-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 in liver results in hepatomegaly, chronic jaundice, enlarged canaliculi, and hepatocellular carcinoma. E-cadherin expression and gap junctions are distorted (85). |

| Alb-Cre | Loss of Cdc42 followed by partial hepatectomy in liver results in delayed recovery with reduced and delayed DNA synthesis associated with dampened JNK and p70S6K signaling (86). |

| Pancreas | |

| Pdx1-Cre | Ablation of Cdc42 in pancreatic progenitors leads to loss of tube formation and up-regulation of acinar cell differentiation associated with polarity defects, including altered Par3 and aPKC localization (42). |

| Eye | |

| LE-Cre | Lens epithelium-specific deletion of Cdc42 leads to decreased filopodia and lens pit invagination through its effector IRSp53 during development (76). |

| Skin | |

| K5-Cre | Keratinocyte-specific Cdc42 deletion showed impaired hair formation and reduced growth of all hair. Increased degradation of β-catenin following decreased GSK-3β and increased axin phosphorylation is seen, which is dependent on PKCζ (77). Loss of Cdc42 in keratinocytes leads to aberrant deposition of basement membrane in keratinocytes and loss of polarization with impaired processing of laminin-5 (78). |

| Blood | |

| Mx1-Cre | HSPC deletion of Cdc42 leads to cell cycle re-entry and hyperproliferation of blood progenitors. It also causes impaired adhesion, homing, migration, and retention that lead to an engraftment failure. Deregulation of c-Myc, p21Cip1, β1-integrin, and N-cadherin expression in HSCs is evident (56). |

| Mx1-Cre | Blood stem/progenitor deletion of Cdc42 results in an increase in early myeloid progenitors and fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Up-regulation of promyeloid genes such as PU.1, C/EBP1α, and Gfi-1 in CMPs and GMPs and down-regulation of the proerythroid gene GATA-2 in MEPs are evident (5, 55). |

| PF4-Cre | Platelet-specific deletion of Cdc42 leads to mild thrombocytopenia and an increase in platelet size. Additionally, Cdc42-deficient platelets have a shorter life span and deficiencies in platelet activation and granule organization, notably through GPIb signaling (87). |

| Immune system | |

| CD19-Cre | Cdc42 deletion at the pro-B/pre-B cell stage leads to impaired B cell development and decreased proliferation and survival. Defects in B cell receptor signaling are attributed to increased ERK and decreased Akt activation (62). |

| Mx1-Cre | Cdc42 deletion in blood stem/progenitor cells leads to impaired leading edge coordination and decreased in vivo motility in dendritic cells, in part through global change of the shape of the actin cytoskeleton (65). |

| Mx1-Cre | Bone marrow deletion of Cdc42 leads to decreased polarity, directionality, and maintenance of the single leading edge in neutrophils. Contractile signals at the uropod are affected through altered CD11b distribution and phosphorylation of MLC (68). |

| Lck-Cre | T cell-specific deletion of Cdc42 leads to dramatic loss of naive T cells. Cdc42 loss results in an increase in Gfi-1 and repressed expression of IL-7 receptor-α. Additionally, it causes an increase in T cell receptor-mediated ERK1/2 activity and T cell proliferation (61). |

| Bone | |

| Ctsk-Cre | Osteoclast-specific deletion of Cdc42 leads to osteopetrosis and reduced bone resorption. M-CSF-stimulated cyclin D expression and phosphorylation of Rb, as well as RANKL-induced osteoclastogenic signals, are altered (84). |

Cardiovascular Regulation

Cardiac organogenesis is characterized by a precise temporal and region-specific regulation of cell proliferation, migration, death, and differentiation that is related to Rho GTPase-mediated signaling (31, 32). Inhibition of Rho GTPase activities through expression of Rho guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI)-α resulted in lethality around embryonic day 10.5 (33) associated with cardiac abnormalities such as an incomplete cardiac looping and lack of chamber maturation, trabeculation, and hypocellularity. Further examination revealed a significant up-regulation of p21Cip, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, and down-regulation of cyclin A. Overexpression of constitutively active Rac1 in the heart caused an early cardiac hypertrophy or dilated cardiac failure (34), whereas cardiac-specific deletion of Rac1 reduced cardiac growth (35). Interestingly, cardiac expression of an active RhoA mutant is associated with atrial enlargement, alterations in the cardiac conduction system, and ventricular dilation as opposed to ventricular hypertrophy (36).

It was recently demonstrated that Cdc42 acts as an antihypertrophic mediator in mouse heart (37). Heart-specific deletion of Cdc42 enhanced the cardiac growth response to both pathological and physiological stimuli and resulted in an inability to activate JNK signaling. Interestingly, an increase in JNK signaling was also seen in Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein (GAP) knock-out mice (22, 38). Restoration of JNK signaling in the heart reversed the enhanced growth effect (37). The involvement of Cdc42 in cardiac hypertrophy was also inferred from studies of microRNAs. Decreased expression of microRNA-133, which targets both Cdc42 and RhoA, was observed in both mouse and human models of cardiac hypertrophy (39).

Pancreatic Development

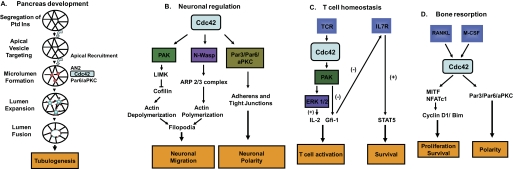

Many organs such as lung, kidney, pancreas, salivary gland, and mammary gland consist of epithelial tubes (40). Tubulogenesis involves a series of dynamic and interdependent cellular processes, including cytoskeletal reorganization, assembly of intercellular complexes, and cell polarization. The molecular mechanisms that integrate cell polarity with tissue architecture during epithelial morphogenesis remain poorly defined. In a three-dimensional organotypic culture of Madin-Darby canine kidney and Caco-2 cells, it was demonstrated that the phosphatase PTEN and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulate Cdc42 and an effector kinase, aPKC, to generate the apical plasma membrane domain and maintain apical-basal polarity (41). Cdc42 knockdown experiments show that Cdc42 regulates epithelial tissue morphogenesis by controlling the spindle orientation during cell division rather than affecting the establishment of apical-basal polarity in individual cells (26). A recent mouse model study of pancreatic progenitors showed that tube formation starts at embryonic day 11.5 by the initiation of scattered microlumens throughout the epithelium (42). These microlumens then expand through the spreading of cell polarization, followed by fusion of lumens and their rearrangement into an interconnected tubular system. In this context, inducible deletion of Cdc42 during pancreatic development revealed that Cdc42 is required for multicellular apical polarization of Par3 and aPKC and is responsible for microlumen formation during the early stages of pancreatic development (Fig. 2A). Loss of tube formation as a consequence of Cdc42 ablation causes a failure to organize pancreatic epithelial progenitors into tubes and subsequently results in an up-regulation of acinar cell differentiation at the expense of duct and endocrine cell differentiation. Significantly, the effect of Cdc42 appears to be mediated by the extracellular matrix and the resulting microenvironment, which in turn determines cell fate. Thus, Cdc42 is critical in initiating the formation of the apical lumens that ultimately combine to form tubules and thus connects cell polarization with differentiation during pancreatic development.

FIGURE 2.

Examples of the signaling role of Cdc42 in selective tissue cell types. A, Cdc42 controls pancreatic progenitor cell polarity and the formation of apical lumens that ultimately combine to form tubules during pancreatic development (adapted from Ref. 42). Ptd Ins, phosphatidylinositol. B, Cdc42 regulates multiple neuronal cell functions. Through the Par3-Par6-aPKC complex, Cdc42 controls neural epithelial progenitor polarity. The PAK-mediated cofilin pathway and N-WASP-mediated Arp2/3 pathway may counterbalance the dynamic actin structures required for neuronal migration and axonal expansion. LIMK, LIM kinase. C, Cdc42 coordinates the survival signal from the IL-7 receptor (IL7R) and the proliferative signal from the T cell receptor (TCR) in regulating naive T cell homeostasis. D, Cdc42 integrates M-CSF- and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenic signals to regulate osteoclast proliferation, survival, and bone resorption.

Nervous System Regulation

Earlier biochemical studies in neuronal cells have shown that Cdc42, along with Rac1, is a positive regulator, whereas RhoA functions as a negative regulator in neurite initiation, axon growth and branching, and spine formation (43–45). In particular, Cdc42 plays a key role in oligodendrocyte differentiation and in neuronal polarity/axon outgrowth and neuronal migration (44, 46). Recent mouse gene targeting studies have demonstrated that Cdc42 participates in the establishment of apical-basal polarity of neural epithelial progenitors (47). Deletion of Cdc42 in mouse telencephalon resulted in a detachment of neural progenitors from the apical/ventricular surface, and this was associated with mislocalization of Par6, aPKC, β-catenin, F-actin, and Numb, the polarity-based components (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the global loss of apical-basal polarity of the neural progenitors can lead to Shh (Sonic Hedgehog)-independent holoprosencephaly, a phenotype of failed bifurcation of the left versus right brain hemisphere (48). Ablation of either Cdc42 or Rac1 in neural crest stem cells shows they are not required for the maintenance, migration, and differentiation of these cells in the early phase of neural crest development; however, Cdc42 is essential for proliferative control during later phases of development when neural crest stem cells acquire responsiveness to mitotic signals (49). Conditional ablation of Cdc42 in mature brain through the use of several promoters to drive Cre recombinase expression resulted in multiple abnormalities, including striking defects in the formation of axon tracts (50). Neurons from Cdc42-null animals showed disrupted cytoskeletal organization, enlargement of growth cones, and inhibition of filopodial dynamics, along with increased inactivation of the Cdc42 effector cofilin. These results suggest that Cdc42 is a key regulator of axon specification (Fig. 2B).

Accumulating evidence indicates that Cdc42 transduces signals to the cytoskeleton at least in part through the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome family of scaffolding proteins (51). N-WASP regulates the formation of dendritic spines and synapses in hippocampal neurons (52). Knockdown of endogenous N-WASP expression by RNA interference or inhibition of its activity by treatment with a specific inhibitor, wiskostatin, causes a significant decrease in the number of spines and excitatory synapses, a phenotype similar to observed when Cdc42 is down-regulated (Fig. 2B) (52).

In the CNS and peripheral nerves, the formation of myelin sheaths is the result of a complex series of events involving oligodendrocyte or Schwann cell progenitor proliferation, directed migration, and the morphological changes associated with axon ensheathment and myelination. Interestingly, ablation of Cdc42 in Schwann cells showed that, although it is required, along with Rac1, for Schwann cell proliferation and the correct formation of myelin sheaths (53), it appears that Rac1, not Cdc42, critically regulates Schwann cell process extension and stability, thereby allowing efficient radial sorting of axon bundles (54).

Blood Development

The role of Rho GTPases, including Cdc42, in blood development has been extensively studied by the mouse gene targeting approach (20, 21, 55). Genetic deletion of Cdc42GAP, a negative regulator of Cdc42, resulted in multiple phenotypes in blood development (5). The gain-of-Cdc42 activity mice were anemic, and their blood stem/progenitor cells displayed impaired cortical F-actin assembly, decreased migration and adhesion, defective engraftment, and elevated JNK-driven apoptosis (5). Conversely, conditional knock-out of Cdc42 from bone marrow resulted in a loss of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) quiescence and massive HSPC egress from bone marrow to the periphery, phenotypes attributable to deregulated β1-integrin, p21Cip, c-Myc, N-cadherin, and possibly other hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) intrinsic factors (56). Interestingly, Cdc42−/− HSPCs displayed impaired F-actin assembly, adhesion, homing, and migration in bone marrow, similar to the results obtained with the Cdc42 gain-of-activity mice, suggesting that non-physiological levels of Cdc42 activity, either higher or lower, may cause similar cellular defects.

Aside from HSPC maintenance, Cdc42 plays a pivotal role in multilineage blood development. Loss of Cdc42 in bone marrow causes both myeloid and erythroid defects, i.e. an increase in early myeloid progenitors that leads to a fatal myeloproliferative disorder and an anemia caused by a block in the early stages of erythropoiesis (57). The cause of the imbalance between myelopoiesis and erythropoiesis in Cdc42−/− HSPCs is intimately associated with changes in the transcriptional program. Promyeloid genes, including PU.1, C/EBP1α, and Gfi-1, were up-regulated in progenitor populations (common myeloid progenitor (CMP), granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP), and megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor (MEP), whereas the proerythroid transcription factor GATA-2 was down-regulated in short-term repopulating HSPC, CMP, and MEP populations (5, 55). In comparison, the Cdc42GAP−/− gain-of-activity mice showed a reduction in cellularity of both fetal liver and bone marrow, number and composition of HSPCs, and erythroid blast-forming unit and colony-forming unit activities (5). Therefore, a physiological level of Cdc42 activity is critically involved in the delicate balance of blood stem/progenitor cell differentiation into myeloid versus erythroid lineages.

Immune System Regulation

As in other systems, Cdc42 was first examined for its role in immunity using dominant-negative and constitutively active mutants (55, 58). Expression of an active Cdc42 mutant in Jurkat T lymphocytes led to increased apoptosis through increased activity of JNK (59). Mice transgenically expressing an active Cdc42 mutant exhibited increased peripheral T cell and thymocyte apoptosis (60). Gene targeting studies revealed recently that, through its effector PAK1 signaling axis, Cdc42 is involved in regulating mature T cell homeostasis by coordinating IL-7 receptor-mediated survival and T cell receptor-mediated proliferation signals (Fig. 2C) (61). Interestingly, contrary to the conventional view of Cdc42 function, loss of Cdc42 resulted in a hyperproliferative phenotype in naive T cells through elevated ERK signaling. In contrast, deletion of cdc42 in HSPCs did not affect common lymphoid progenitor development; however, deletion of cdc42 in the pro-B/pre-B cell stage resulted in blockage of B cell development at both T1 and later stages (62), implicating Cdc42 in B cell precursor differentiation. Cdc42-deficient B cells exhibited impaired proliferation and survival, effects associated with a defect in B cell receptor signaling through ERK and Akt, and BAFF receptor presentation. Distinct from that of T cell or hematopoietic progenitor cells, Cdc42 appeared to be dispensable for SDF-1α- or BLC-induced B cell migration.

In dendritic cells (DCs), Cdc42 is increasingly expressed during development from HSCs, remains highly active in immature DCs, and can be further up-regulated by maturation stimuli (63). Developmental control of endocytosis in DCs also seems to be regulated through Cdc42 (64). The migratory activity of DCs is controlled by Cdc42 because Cdc42−/− DCs had impaired leading edge coordination and ultimately showed a loss of in vivo motility (65). In addition, Cdc42 controls the transport of essential immunostimulatory molecules to the DC surface (63). In neutrophils, Cdc42 has been recognized as a critical regulator of neutrophil polarity and may coordinate other Rho GTPases, RhoA and Rac1/2 in particular, in establishing the trailing and leading edges of migrating cells (66–68). In a gain-of-Cdc42 activity mouse model, Cdc42 was found to be required for neutrophil movement and directionality through distinct MAPK pathways (67). On the other hand, Cdc42 knock-out caused a loss of polarity mediated through the CD11b integrin-RhoA-Rho kinase-phosphorylated MLC signaling cascade (68). These studies reinforce the importance of a balanced Cdc42 activity in the maintenance of polarity in innate immune cell responses and clarify the signaling pathways involved.

Eye Development

Like many organs, the development of the eye involves complex processes, including the invagination and folding of layers of cells. These dramatic changes are known to involve cell polarization, as well as actin and microtubule dynamics. Expression of Cdc42 has been characterized in several model systems of eye development (69–71). In Drosophila, Cdc42 is thought to regulate photoreceptor morphogenesis through its downstream effector Mbt, a PAK homolog (72). Mbt mutants showed a decrease in neurons in the brain and eye through a loss of adherens junction localization and kinase activity in photoreceptor cells, both of which are dependent on Cdc42. Loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila cdc42 resulted in failure of epithelial cells to elongate, leading to defects in ommatidial units and photoreceptor differentiation (73). Additionally, activation of Cdc42 through the expression of a constitutively active mutant induced ectopic antennae, whereas a dominant-negative mutant caused a small eye phenotype (74). In mice, lens-specific overexpression of RhoGDI disrupted membrane translocation of Cdc42, as well as Rac1 and RhoA, resulting in defects in lens fiber migration, elongation, and organization (75). Targeted deletion of Cdc42 in the lens epithelia caused a loss of filopodia in these cells and resulted in a reduction of lens pit invagination during development, and this effect was mediated through the effector IRSp53 (76). Close inspection revealed that the extensions seen between the base of the lens and presumptive retina are filopodia coming from the presumptive lens, putting to rest conflicting earlier views. Furthermore, these filopodia are essential in tethering the two epithelial layers of the lens and retina to precisely coordinate this morphogenetic event.

Skin Development and Maintenance

Several studies in the last few years have addressed the function of Cdc42 in differentiation during skin development. A keratinocyte-specific cdc42 deletion in mice did not cause observable defects at birth but displayed impaired hair formation and growth at 2 weeks of age (77). Within 4 weeks, the mutant mice had lost all hair. Examination of the hair follicles from these mice revealed dramatic changes, i.e. the loss of Cdc42 skewed epithelial progenitor cells in the hair follicles from a hair follicle keratinocyte fate to an epidermal keratinocyte fate, and the mechanism appeared to hinge on a Cdc42-dependent regulation of β-catenin. Deletion of Cdc42 in keratinocytes led to aberrant deposition of basement membrane components and impaired processing of laminin-5 in segments of the dermal-epidermal junction (78), suggesting that Cdc42 is required for the maintenance of the basement membrane. The Cdc42 effector N-WASP has recently been implicated in several skin processes (79). Conditional knock-out of N-Wasp from epidermal keratinocytes and other squamous epithelia resulted in severe alopecia, epidermal hyperproliferation, and facial ulcerations, as well as abnormal proliferation and ultimate depletion of skin progenitors over time (79). Importantly, a direct link between N-WASP and Wnt signaling was found, confirming a Cdc42-N-WASP-β-catenin signaling cascade. The N-WASP deficiency resulted in decreased GSK-3β phosphorylation, reduced nuclear β-catenin, and decreased Wnt-dependent transcription in follicular keratinocytes, implicating N-WASP as a positive regulator of β-catenin-dependent transcription.

Bone Modeling Regulation

Osteoclast activation requires cytoskeletal reorganization that may involve Cdc42. Earlier studies using inhibitors and mutant expression in vitro yielded conflicting results regarding the role of Rho GTPases (80, 81). Additional studies suggested roles for the Cdc42 effector WASP-Arp2/3 in actin ring formation and bone resorption (82, 83). A recent comprehensive examination of the role of Cdc42 in osteoclast regulation in mouse models was able to convincingly implicate Cdc42 in the RANKL-mediated bone resorption process (84). Loss of Cdc42 resulted in osteopetrosis and resistance to ovariectomy-induced bone loss, whereas animals with constitutively elevated Cdc42 activity were osteoporotic. Cdc42-deficient osteoclasts had reduced bone resorption, whereas osteoclasts with elevated Cdc42 activity showed increased resorption. In this process, Cdc42 was shown to regulate macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-stimulated cyclin D expression and phosphorylation of Rb, leading to osteoclast proliferation and induction of Bim and caspase-3, which are involved in osteoclast apoptosis (Fig. 2D). Moreover, Cdc42 was found to be essential for M-CSF- and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenic signals, including MITF and NFATc1, and to be a component of the Par3-Par6-aPKC polarization complex (84). These combined genetic and biochemical studies demonstrate that Cdc42 regulates osteoclast formation and function and may be a useful target for bone loss prevention.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Decade-old biochemical studies of the signaling function of Cdc42, along with other Rho GTPases, have provided a wealth of its possible roles in cell regulation. It is evident that Cdc42 has integral functions in many cell systems and achieves this by mediating signaling through multiple pathways (67, 77). Recent mouse gene targeting studies in diverse tissue/organ cell types have provided powerful genetic evidence for physiological roles of Cdc42 that, in some circumstances, contradicts conventional wisdom derived from previous in vitro studies. It is clear that the function and signaling pathways regulated by Cdc42 are tissue- and cell type-specific, and the general principles of Cdc42 function defined by in vitro methods or from one tissue cell type may or may not apply to another cell type in in vivo situations (Table 1). One unifying theme from these studies appears to be that Cdc42 is critically involved in actin-based morphogenesis of diverse cell types, and it serves as a central regulator of cell polarity, the phenotype of which is manifested in unique physiologies of distinct tissues. Such an expansion of our knowledge of the physiological function of Cdc42 will undoubtedly accelerate translation to future therapy in areas including immunosuppression, stem cell mobilization, anti-inflammation, and anticancer metastasis.

It is important to note that the gene targeting approach has its inherent limitations such that other related Rho GTPase pathways may insert a compensatory effect upon Cdc42 loss, and the complete abrogation of Cdc42 does not truly reflect certain functional outputs resulting from relatively subtle changes of Cdc42 activity under normal or pathological challenges. To this end, RNA interference technology provides a complementary method, especially when examining the role of overexpressed or elevated activity of Cdc42 in diseases such as cancer. Future mouse genetic studies by knock-in or inducible systems of Cdc42 mutants under Cdc42 native promoter control, combined with specific effector knock-out studies, will be useful to attribute specific downstream pathways regulated by Cdc42 causally to its multifaceted functions in defined cell types. To further apply the mouse studies to benefit human pathophysiology conditions will be an aspiring goal of the field that is poised to see potential translations of the knowledge gained.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA150547, R01 HL085362, and P30 DK090971. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2011 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2012.

- MLC

- myosin light chain

- aPKC

- atypical PKC

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GDI

- guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- HSPC

- hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- DC

- dendritic cell

- M-CSF

- macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- CMP

- common myeloid progenitor

- GMP

- granulocyte/monocyte progenitor

- MEP

- megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hall A. (1998) Science 279, 509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burridge K., Wennerberg K. (2004) Cell 116, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ridley A. J. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 471–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moon S. Y., Zheng Y. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13, 13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang L., Yang L., Filippi M. D., Williams D. A., Zheng Y. (2006) Blood 107, 98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson D. I., Pringle J. R. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 143–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drubin D. G. (1991) Cell 65, 1093–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson D. I. (1999) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 54–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gotta M., Abraham M. C., Ahringer J. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 482–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kay A. J., Hunter C. P. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 474–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murphy A. M., Montell D. J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 133, 617–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etienne-Manneville S. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 1291–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lamarche N., Tapon N., Stowers L., Burbelo P. D., Aspenström P., Bridges T., Chant J., Hall A. (1996) Cell 87, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Servotte S., Zhang Z., Lambert C. A., Ho T. T., Chometon G., Eckes B., Krieg T., Lapière C. M., Nusgens B. V., Aumailley M. (2006) Protoplasma 229, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yasuda S., Oceguera-Yanez F., Kato T., Okamoto M., Yonemura S., Terada Y., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S. (2004) Nature 428, 767–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vanni C., Ottaviano C., Guo F., Puppo M., Varesio L., Zheng Y., Eva A. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 1675–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bustelo X. R., Sauzeau V., Berenjeno I. M. (2007) BioEssays 29, 356–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cerione R. A. (2004) Trends Cell Biol. 14, 127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Erickson J. W., Cerione R. A. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang L., Zheng Y. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heasman S. J., Ridley A. J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 690–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang L., Wang L., Zheng Y. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4675–4685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin D., Edwards A. S., Fawcett J. P., Mbamalu G., Scott J. D., Pawson T. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noda Y., Takeya R., Ohno S., Naito S., Ito T., Sumimoto H. (2001) Genes Cells 6, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki A., Ohno S. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 979–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaffe A. B., Kaji N., Durgan J., Hall A. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 183, 625–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A. (2002) Nature 420, 629–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwartz M. A., Meredith J. E., Kiosses W. B. (1998) Oncogene 17, 625–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woo S., Gomez T. M. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 1418–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Czuchra A., Wu X., Meyer H., van Hengel J., Schroeder T., Geffers R., Rottner K., Brakebusch C. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4473–4484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sucov H. M. (1998) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60, 287–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fishman M. C., Chien K. R. (1997) Development 124, 2099–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wei L., Imanaka-Yoshida K., Wang L., Zhan S., Schneider M. D., DeMayo F. J., Schwartz R. J. (2002) Development 129, 1705–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sussman M. A., Welch S., Walker A., Klevitsky R., Hewett T. E., Price R. L., Schaefer E., Yager K. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105, 875–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Satoh M., Ogita H., Takeshita K., Mukai Y., Kwiatkowski D. J., Liao J. K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7432–7437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sah V. P., Minamisawa S., Tam S. P., Wu T. H., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Ross J., Jr., Chien K. R., Brown J. H. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1627–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maillet M., Lynch J. M., Sanna B., York A. J., Zheng Y., Molkentin J. D. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3079–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang L., Yang L., Debidda M., Witte D., Zheng Y. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1248–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carè A., Catalucci D., Felicetti F., Bonci D., Addario A., Gallo P., Bang M. L., Segnalini P., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Elia L., Latronico M. V., Høydal M., Autore C., Russo M. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Ellingsen O., Ruiz-Lozano P., Peterson K. L., Croce C. M., Peschle C., Condorelli G. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lubarsky B., Krasnow M. A. (2003) Cell 112, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin-Belmonte F., Gassama A., Datta A., Yu W., Rescher U., Gerke V., Mostov K. (2007) Cell 128, 383–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kesavan G., Sand F. W., Greiner T. U., Johansson J. K., Kobberup S., Wu X., Brakebusch C., Semb H. (2009) Cell 139, 791–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Negishi M., Katoh H. (2002) J. Biochem. 132, 157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Govek E. E., Newey S. E., Van Aelst L. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Linseman D. A., Loucks F. A. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 657–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Osmani N., Vitale N., Borg J. P., Etienne-Manneville S. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 2395–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cappello S., Attardo A., Wu X., Iwasato T., Itohara S., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Eilken H. M., Rieger M. A., Schroeder T. T., Huttner W. B., Brakebusch C., Götz M. (2006) Nat. Neurosci 9, 1099–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen L., Liao G., Yang L., Campbell K., Nakafuku M., Kuan C. Y., Zheng Y. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16520–16525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fuchs S., Herzog D., Sumara G., Büchmann-Møller S., Civenni G., Wu X., Chrostek-Grashoff A., Suter U., Ricci R., Relvas J. B., Brakebusch C., Sommer L. (2009) Cell Stem Cell 4, 236–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Garvalov B. K., Flynn K. C., Neukirchen D., Meyn L., Teusch N., Wu X., Brakebusch C., Bamburg J. R., Bradke F. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 13117–13129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rohatgi R., Ma L., Miki H., Lopez M., Kirchhausen T., Takenawa T., Kirschner M. W. (1999) Cell 97, 221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wegner A. M., Nebhan C. A., Hu L., Majumdar D., Meier K. M., Weaver A. M., Webb D. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15912–15920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thurnherr T., Benninger Y., Wu X., Chrostek A., Krause S. M., Nave K. A., Franklin R. J., Brakebusch C., Suter U., Relvas J. B. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 10110–10119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Benninger Y., Thurnherr T., Pereira J. A., Krause S., Wu X., Chrostek-Grashoff A., Herzog D., Nave K. A., Franklin R. J., Meijer D., Brakebusch C., Suter U., Relvas J. B. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 1051–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mulloy J. C., Cancelas J. A., Filippi M. D., Kalfa T. A., Guo F., Zheng Y. (2010) Blood 115, 936–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang L., Wang L., Geiger H., Cancelas J. A., Mo J., Zheng Y. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5091–5096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang L., Wang L., Kalfa T. A., Cancelas J. A., Shang X., Pushkaran S., Mo J., Williams D. A., Zheng Y. (2007) Blood 110, 3853–3861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bustelo X. R. (2002) BioEssays 24, 602–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chuang T. H., Hahn K. M., Lee J. D., Danley D. E., Bokoch G. M. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1687–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Na S., Li B., Grewal I. S., Enslen H., Davis R. J., Hanke J. H., Flavell R. A. (1999) Oncogene 18, 7966–7974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guo F., Hildeman D., Tripathi P., Velu C. S., Grimes H. L., Zheng Y. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18505–18510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guo F., Velu C. S., Grimes H. L., Zheng Y. (2009) Blood 114, 2909–2916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jaksits S., Bauer W., Kriehuber E., Zeyda M., Stulnig T. M., Stingl G., Fiebiger E., Maurer D. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 1628–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Garrett W. S., Chen L. M., Kroschewski R., Ebersold M., Turley S., Trombetta S., Galán J. E., Mellman I. (2000) Cell 102, 325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lämmermann T., Renkawitz J., Wu X., Hirsch K., Brakebusch C., Sixt M. (2009) Blood 113, 5703–5710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Van Keymeulen A., Wong K., Knight Z. A., Govaerts C., Hahn K. M., Shokat K. M., Bourne H. R. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Szczur K., Xu H., Atkinson S., Zheng Y., Filippi M. D. (2006) Blood 108, 4205–4213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Szczur K., Zheng Y., Filippi M. D. (2009) Blood 114, 4527–4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Santos-Bredariol A. S., Santos M. F., Hamassaki-Britto D. E. (2002) J. Neurocytol. 31, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Muñoz-Descalzo S., Gómez-Cabrero A., Mlodzik M., Paricio N. (2007) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 51, 379–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mitchell D. C., Bryan B. A., Liu J. P., Liu W. B., Zhang L., Qu J., Zhou X., Liu M., Li D. W. (2007) Mol. Vis. 13, 1144–1153 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schneeberger D., Raabe T. (2003) Development 130, 427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Genova J. L., Jong S., Camp J. T., Fehon R. G. (2000) Dev. Biol. 221, 181–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Go M. J. (2005) Dev. Growth Differ. 47, 225–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Maddala R., Reneker L. W., Pendurthi B., Rao P. V. (2008) Dev. Biol. 315, 217–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chauhan B. K., Disanza A., Choi S. Y., Faber S. C., Lou M., Beggs H. E., Scita G., Zheng Y., Lang R. A. (2009) Development 136, 3657–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wu X., Quondamatteo F., Lefever T., Czuchra A., Meyer H., Chrostek A., Paus R., Langbein L., Brakebusch C. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 571–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wu X., Quondamatteo F., Brakebusch C. (2006) Matrix Biol. 25, 466–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lyubimova A., Garber J. J., Upadhyay G., Sharov A., Anastasoaie F., Yajnik V., Cotsarelis G., Dotto G. P., Botchkarev V., Snapper S. B. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 446–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Fukuda A., Hikita A., Wakeyama H., Akiyama T., Oda H., Nakamura K., Tanaka S. (2005) J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 2245–2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chellaiah M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32930–32943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Calle Y., Jones G. E., Jagger C., Fuller K., Blundell M. P., Chow J., Chambers T., Thrasher A. J. (2004) Blood 103, 3552–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hurst I. R., Zuo J., Jiang J., Holliday L. S. (2004) J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ito Y., Teitelbaum S. L., Zou W., Zheng Y., Johnson J. F., Chappel J., Ross F. P., Zhao H. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1981–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. van Hengel J., D'Hooge P., Hooghe B., Wu X., Libbrecht L., De Vos R., Quondamatteo F., Klempt M., Brakebusch C., van Roy F. (2008) Gastroenterology 134, 781–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yuan H., Zhang H., Wu X., Zhang Z., Du D., Zhou W., Zhou S., Brakebusch C., Chen Z. (2009) Hepatology 49, 240–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pleines I., Eckly A., Elvers M., Hagedorn I., Eliautou S., Bender M., Wu X., Lanza F., Gachet C., Brakebusch C., Nieswandt B. (2010) Blood 115, 3364–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]