Abstract

We define two classes of calreticulin mutants that retain glycan binding activity; those that display enhanced or reduced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity, due to conformational effects. Under normal conditions, neither set of mutants significantly impacts the ability of calreticulin to mediate assembly and trafficking of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, which are calreticulin substrates. However, in cells treated with thapsigargin, which depletes endoplasmic reticulum calcium, major histocompatibility complex class I trafficking rates are accelerated coincident with calreticulin secretion, and detection of cell-surface calreticulin is dependent on its polypeptide binding conformations. Together, these findings identify a site on calreticulin that is an important determinant of the induction of its polypeptide binding conformation and demonstrate the relevance of the polypeptide binding conformations of calreticulin to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced interactions.

Keywords: Antigen Processing, Calcium-binding Proteins, Chaperone Chaperonin, ER Stress, Intracellular Trafficking, Protein Folding, Calreticulin, MHC Class I

Introduction

Calreticulin is a soluble protein chaperone that binds monoglucosylated N-linked oligosaccharides on newly synthesized substrate glycoproteins in the ER,2 acting along with its membrane-bound homolog calnexin and its partner thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 to maintain quality control of glycoprotein folding (for review, see Ref. 1). Calreticulin also suppresses the irreversible aggregation of non-glycosylated polypeptides in vitro (2). This activity is enhanced under conditions associated with ER stress such as calcium depletion and heat shock (3). The nature of the polypeptide binding site(s) of calreticulin and its relevance to calreticulin-mediated protein folding in a cell remain poorly understood.

Calreticulin plays an important role in the MHC class I assembly pathway (4). It is a component of the MHC class I peptide loading complex (PLC), which also contains the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP), tapasin, and ERp57 (for review, see Refs. 5 and 6). Calreticulin-deficient cells have reduced cell-surface MHC class I and display defects in the quality control of MHC class I peptide loading (4). Additionally, mutating certain residues within the glycan or ERp57 binding sites of calreticulin reduces its ability to aid in MHC class I assembly (7), although other mutants within these sites retain their abilities to be recruited into the PLC (8). It has been suggested that the calreticulin polypeptide binding site is important for its recruitment to the PLC (8), but this possibility has been difficult to directly test due to a lack of knowledge about the nature of the polypeptide binding site. Here we identify and characterize two classes of calreticulin mutants that retain glycan binding abilities; that is, overactive polypeptide chaperones and underactive polypeptide chaperones. The function of these mutants in MHC class I assembly was examined under normal conditions and ER stress conditions. Under normal conditions, MHC class I assembly and trafficking are not altered in the context of the different calreticulin constructs. However, after calcium depletion in the ER, calreticulin secretion was observed, and polypeptide binding conformations of calreticulin were important for mediating interactions with cell-surface substrates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs, Protein Expression, and Purifications

Generation of mutant mCRT constructs was undertaken by site-directed, ligase-independent mutagenesis (SLIM) (9) or the Finnzymes Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit using mCRT in pMSCV-puro, mCRT-FLAG in pMSCV-puro (encoding mCRT containing a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag inserted before the KDEL sequence) (7), or mCRT in the pCMV-SPORT6 (ATCC, MGC-6209) vector as templates and different primers as specified in supplemental Table SI. The mCRT construct in pCMV-SPORT6 was subsequently transferred into the pMSCV-puro vector by PCR amplification with primers specified in supplemental Table SI, digestion with XhoI and Hpa1, and ligation into pMSCV-puro digested with the same enzymes. All mCRT retroviral constructs retained the mCRT signal sequence and KDEL ER retention motif. mCRT(W302A) was generated as described in Del Cid et al. (7). Ligation-independent cloning was used to transfer all mCRT constructs into the pMCSG7 vector for bacterial expression, as previously described (7). All constructs were sequenced by the University of Michigan DNA Sequencing Core. All bacterially expressed mCRT constructs lacked the signal sequence and contained an N-terminal MHHHHHHSSGVDLGTENLYFQSNA fusion sequence for nickel affinity chromatography. mCRT purifications were undertaken using nickel affinity chromatography (7). Purified concentrated calreticulin constructs were analyzed by gel filtration at 4 °C using a Highload 16/60 Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare). Buffer used was 20 mm Hepes, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5. Ligation-independent cloning was used to clone a truncated version (LLO(d123)) of a full-length LLO construct (10) into the pMCSG7 vector using primers listed in supplemental Table SI. LLO and LLO(d123) purifications were undertaken by nickel affinity chromatography as previously described (7). Protein concentration was determined measuring absorbance at 280 nm. Extinction coefficients of 82975, 77240, and 35300 m−1 cm−1, respectively, were used to estimate concentrations of mCRT, LLO, and LLO(d123).

Thermostability Analyses by Sypro Orange Binding

These analyses were undertaken as previously described (7, 11, 12). Proteins (16 μm) were incubated in buffer (20 mm Hepes, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5) and 1× Sypro Orange Stain (Invitrogen) diluted from a 5000× stock solution in the presence or absence of 48 μm Glcα1–3Manα1–2Manα1–2Man (G1M3) (Alberta Research Council) in a total reaction volume of 10 μl. Thermal scans were performed using an ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System using temperature increments of 1 °C starting at 25 °C. Within an experiment, each condition was analyzed in triplicate wells. Fluorescence emission was measured across different wavelength bins, and the bin with maximum fluorescence was chosen for further analysis. Fluorescence was normalized within wells as % maximum fluorescence ((Fobs − Fmin)/(Fmax − Fmin) × 100) and plotted against the sample temperature.

Aggregation Assays

In gel-based assays, 1 μm LLO or LLO(d123) was incubated with purified mCRT constructs (4–16 μm) at 37 °C for 1 h. Assays were conducted in the presence of 0.5 mm CaCl2 unless specified as −Ca2+, which were undertaken in 5 mm EDTA. After incubation, aggregated proteins were separated from solution by microcentrifugation at maximum speed for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatants containing non-aggregated protein were removed, and the pellets containing the aggregated protein were resuspended in an equal volume of buffer. Proteins present in the supernatants and pellets were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized with a Coomassie Blue stain. Protein band intensity was quantified using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare) and used as a measure of aggregation suppression activity of calreticulin. For LLO aggregation, LLO pellets under each mCRT condition were compared with pellets of LLO in the absence of mCRT. For LLO(d123) aggregation, LLO(d123) pellets were quantified as a percentage of the total intensity of the pair of pellet and supernatant bands combined.

Cell Cultures

Calreticulin-deficient K42 cells (4) or wild type counterparts (K41) were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin. Thapsigargin (EMD Biochemicals) was reconstituted in DMSO at a concentration of 5 mm and subsequently diluted 1000-fold in media with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 units/ml of penicillin (Invitrogen) for a final drug concentration of 5 μm. 7 ml of drug-containing media were added to cells in a 10-cm dish and incubated for 5 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 before drug media was removed. Bosc cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) containing 4.5 g/liter glucose, l-glutamine, and 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml of penicillin (Invitrogen). For generation of retroviral supernatants, 5.5 μg of pMSCV-puro vector (encoding different mCRT or control vector lacking mCRT) DNA was mixed with 4 μg of pCL-EcoDNA and 0.5 μg of VSV-G encoding plasmid and added to a mixture of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science). After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the mixture was added to Bosc cells that had been grown to 70% confluency in a 10-cm tissue culture dish. Media were changed after 24 h, and after 48 h, supernatants containing retroviruses were harvested and used to infect calreticulin-deficient K42 cells.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric assays to assess the abilities of different mutants to restore MHC class I cell-surface expression were undertaken as previously described (7). For cell-surface MHC class I and thapsigargin-induced cell-surface calreticulin analyses by flow cytometry, infected K42 cells were detached with PBS/EDTA, washed, and then resuspended in flow cytometry buffer containing MHC class I antibody (1:100 dilution of ascites fluid) (anti-H2-Kb; ATCC HB-176) or chicken anti-calreticulin (Pierce) (2.5 μg/ml) with or without preincubation of the calreticulin-specific antibody with the peptide KEQFLDGDAWTNRWVESKHK (1 mm) for 30 min. The peptide is a calreticulin-derived sequence against which the antibody was raised. Cells were washed two times with buffer and then resuspended in 100 μl of buffer containing goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (1:500) for MHC class I assays or donkey anti-chicken antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (1:250) for calreticulin assays and incubated for 15 min on ice. Cells were washed two times and then resuspended in a 1× dilution of annexin V conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Biosciences) and 7-aminoactinomysin D in annexin V binding buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm CaCl2), and data for each sample were collected on the FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric analyses were performed using WinMDI Version 2.9.

Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblots

K42 cells expressing or lacking mCRT constructs were harvested and lysed in digitonin lysis buffer (10 mm Na2HPO4, 10 mm Tris, 130 mm NaCl, 1% digitonin, complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors, pH 7.5). Cells were lysed on ice for 1 h followed by a 30-min centrifugation to remove cell debris. Supernatants were normalized for protein using BCA assay (Pierce). An aliquot from each cell type was boiled for 5 min with SDS and DTT for lysate samples, and equal protein amounts were incubated with or without antibodies overnight at 4 °C for immunoprecipitations. Samples were then centrifuged to remove precipitated proteins and incubated for 2 h with Protein G beads (GE Healthcare). Beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer containing 0.1% digitonin. Samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon membranes (Millipore) for immunoblotting. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in TBS for 1 h at room temperature followed by an overnight incubation with primary antibody in TBS + 0.05% Tween 20 (TTBS) at 4 °C. Membranes were washed for 2 h in TTBS, incubated for 30 min with secondary antibody, and washed again for 2 h. Chemiluminescence was detected using the GE Healthcare Amersham Biosciences ECL Plus kit.

The following antibody was used to immunoisolate TAP1 protein: rabbit anti-mouse TAP1 serum (1:15) (kindly provided by Dr. Ted Hansen). The following antibodies were used in immunoblotting analyses: goat anti-TAP1 antibody (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; catalog #sc-11465), goat antibody specific to the N terminus of mCRT (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog #sc-7431), rabbit anti-ERp57 antibody (1:3000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog # sc-28823), hamster anti-tapasin (1:3000) (kindly provided by Dr. Ted Hansen), and rabbit anti Kb antiserum EX8 (1:7500) (kindly provided by Dr. Jonathan Yewdell). Secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were all conjugated to horseradish peroxidase: mouse anti-rabbit (light chain specific), bovine anti-goat, and goat anti-hamster.

Pulse-Chase Analyses

K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT) or various mCRT mutants were incubated for 45 min with DMEM lacking cysteine and methionine and containing 5% dialyzed fetal bovine serum. Cells were metabolically labeled for 10 min with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine and chased for the indicated times. Cells were lysed by incubation for 45 min on ice in 10 mm Tris, 10 mm phosphate, 130 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.5, centrifuged for 30 min at full speed in a microcentrifuge. Supernatants were collected and immunoprecipitated for 2 h at 4 °C with 10 μl of Y3 antibody (mouse anti-H2-Kb) and then for 1 h with 20 μl of protein G beads (GE Healthcare). Beads were washed three times with 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer and boiled for 5 min in the presence of SDS and DTT. Supernatants were removed, and half the samples were treated with endoglycosidase Hf (New England Biolabs) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, gels were dried, and radiography images were acquired on a Typhoon Scanner. Band intensities were quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). Some cells, as indicated, were thapsigargin-treated before the start of the assay as described above.

Supernatant Immunoprecipitations

The day before drug treatment, 1 × 106 cells were seeded in a 10-cm dish and allowed to grow overnight. The next day the media were removed, and cells were treated with thapsigargin as described above. Supernatant from two 10-cm plates for each condition was then centrifuged to remove cell debris, transferred to a fresh tube, and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-mCRT antibody (1:15,000) (Abcam; catalog #ab2907) rotating at 4 °C. The following day samples were centrifuged to remove precipitated proteins, transferred to new tubes, and incubated for 5 h with Protein G beads (GE Healthcare). The beads were then washed three times with 1 ml of 1% Nonidet P-40 wash buffer and then boiled in the presence of SDS and DTT. The entire sample was loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting was performed as described in the protocol for immunoprecipitations.

RESULTS

Calreticulin Conformations Impact Its in Vitro Chaperone Activity

To better understand residues contributing to polypeptide-based substrate recognition by calreticulin, a mutational analysis of mCRT was conducted within its the globular domain targeting hydrophobic residues that were predicted to be surface-exposed or occurring in sequence proximity to surface-exposed hydrophobic residues (Fig. 1A, supplemental Table SII). We excluded hydrophobic surface-exposed residues contained within the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the globular domain as well as those contained within the P domain, as calreticulin truncation constructs lacking these regions retain polypeptide-specific chaperone activity (Refs. 7 and 13 and data not shown). W302A was included in the analysis as a mutant deficient in glycan binding and one that displays induced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity (7). H153A was included as it has previously been suggested to be deficient in polypeptide-specific chaperone activity when measured at 44–45 °C (14).

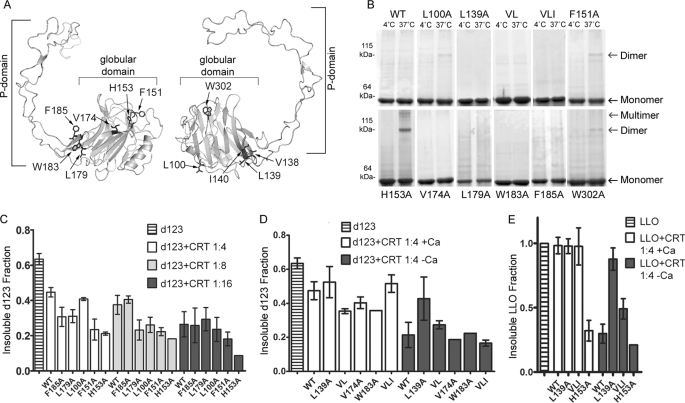

FIGURE 1.

Calreticulin conformations impact its in vitro chaperone activity. A, shown is a structural model for mCRT (34) derived from the crystal structure of its homolog calnexin (35). PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to render the structures. Two different views are shown that illustrate locations and identities of mutants characterized in this study. B, native PAGE gels of mCRT(WT) and mutants, after purifications of monomer peaks by gel filtration (supplemental Fig. S1, show representative gel filtration profiles for mutant protein purifications, with brackets indicating the fractions that were considered monomeric). Proteins (8 μm) were incubated for 1 h at 4 or 37 °C in buffer containing 0.5 mm Ca2+ followed by native-PAGE separation and Coomassie Blue staining. Data are representative of multiple experiments. C, quantifications of chaperone activities of calreticulin mutants toward the substrate LLO(d123) are shown. Substrate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in buffer containing in 0.5 mm Ca2+ in the absence or presence of wild type or mutant mCRT proteins. Tested molar ratios of LLO(d123):mCRT are indicated. LLO(d123) present in the pellet fraction was quantified as ratio relative to the total LLO(d123) present in pellet and supernatant fractions. Data for each mutant are the average of 2–3 independent experiments or from a single analysis (H153A at the 1:8 and 1:16 ratios). D, analyses were similar to C, with the difference that buffers contained either 0.5 mm Ca2+(+Ca) or 5 mm EDTA (−Ca). Data for each mutant are averaged from two-three independent experiments or represent a single analysis (W183A under both conditions and V174A in the −Ca condition). E, analyses were similar to D, with the difference that the substrate protein used was full-length LLO, and quantifications were done of each pellet fraction and expressed as a fraction of the pellet in the LLO alone condition. For each mutant, data are averaged from multiple independent experiments or from a single analysis (H153A in the −Ca condition). Representative gels for C-E are shown in supplemental Fig. S2.

Structural integrities of the mutant proteins were assessed by gel filtration analysis of purified proteins. mCRT(WT) and all mutants were all predominantly in monomeric form, although significant levels of oligomeric species were observed with mCRT(L179A) and mCRT(F185A) (supplemental Fig. S1E). In all cases, fractions corresponding to the monomeric peak of each protein (supplemental Fig. S1, A–F) were collected and used for further in vitro analysis (Fig. 1). By native-PAGE analyses, there was a lower recovery of monomeric mCRT(L179A) and mCRT(F185A) compared with other proteins, reflecting the re-equilibration of gel filtration-purified monomers into multiple oligomeric species (Fig. 1B). All other mutants were predominantly monomeric at 4 °C as was mCRT(WT). After incubation at 37 °C, mCRT(L100A), mCRT(F151A), and mCRT(W302A) formed detectable dimers, whereas dimers were most pronounced with mCRT(H153A) (Fig. 1B).

mCRT mutants varied in their intrinsic conformational stabilities as assessed by thermostability measurements that quantified mCRT binding to the hydrophobic dye, Sypro Orange, using a previously described assay (7) (Table 1). mCRT(H153A) displayed the lowest mean Tm among all mCRT tested, of 43.09 ± 1.84 °C, whereas mCRT(L139A) displayed the highest mean Tm of 49.23 ± 0.31 °C (Table 1). As previously reported (7), mCRT(WT) displayed a Tm of 47.78 ± 0.45 °C. The Tm was not significantly increased for mCRT(V138A/L139A) relative to mCRT(WT) (abbreviated henceforth as mCRT(VL)), whereas the triple mutant mCRT(V138A/L139A/I140A) (abbreviated henceforth as mCRT(VLI)) showed reduced stability relative to mCRT(WT) (Table 1). Thus, mutations in the 138–140 region of mCRT significantly and differentially impact its conformational stability.

TABLE 1.

Thermostabilities of different mCRT constructs assessed by binding to Sypro Orange

The indicated purified mCRT constructs in 0.5 mm Ca2+ were incubated with the fluorophore Sypro Orange alone or with G1M3 tetrasaccharide and subjected to a thermal stability analysis using a real-time PCR machine. Compiled Tm values for all constructs are shown. S.E. indicates the standard error of the mean Tm value measurement. Data are averaged across two-six independent analyses (indicated by n), each performed in triplicate. ΔTm indicates the observed increase in Tm value for each mCRT construct in the presence of G1M3.

| Constructs |

Tm ± S.E. (n) |

ΔTm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Protein + G1M3 | ||

| ° C | ° C | ||

| mCRT(WT) | 47.78 ± 0.45 (6) | 50.95 ± 0.35 (6) | 3.17 |

| mCRT(L100A) | 44.94 ± 0.45 (2) | 48.72 ± 0.35 (2) | 3.78 |

| mCRT(L139A) | 49.23 ± 0.31 (3) | 51.72 ± 0.42 (2) | 2.49 |

| mCRT(VL) | 47.99 ± 0.56 (2) | 50.44 ± 0.17 (2) | 2.45 |

| mCRT(VLI) | 45.58 ± 0.40 (3) | 49.10 ± 1.31 (2) | 3.52 |

| mCRT(F151A) | 44.28 ± 1.32 (2) | 48.72 ± 0.52 (2) | 4.44 |

| mCRT(H153A) | 43.09 ± 1.84 (2) | 47.85 ± 2.37 (2) | 4.76 |

| mCRT(V174A) | 46.61 ± 0.24 (2) | 50.46 ± 0.87 (2) | 3.85 |

| mCRT(L179A) | 48.46 ± 1.49 (2) | 50.10 ± 0.63 (2) | 1.64 |

| mCRT(W183A) | 47.20 ± 0.30 (4) | 48.94 ± 0.20 (3) | 1.74 |

| mCRT(F185A) | 45.73 ± 0.06 (2) | 49.37 ± 0.27 (2) | 3.64 |

| mCRT(W302A) | 44.82 ± 0.94 (3) | 45.67 ± 0.95 (3) | 0.85 |

We previously also showed that glycan (G1M3 tetrasaccharide) binding causes a significant right shift of the Tm value for mCRT(WT) but not for mutants deficient in glycan binding (7). As shown previously (7), the Tm for mCRT(WT) shifted to 50.95 ± 0.35 °C in the presence of G1M3 (Table 1), corresponding to an average G1M3-induced Tm shift of 3.2 °C. In contrast, a much smaller shift of 0.85 °C was observed for mCRT(W302A), the mutant within the predicted glycan binding site. All other mutants displayed ΔTm values of 2-fold or greater increase in Tm compared with mCRT(W302A) (Table 1), suggesting that all mutants are capable of glycan binding, as expected based on the design of the mutations to target residues outside of the predicted glycan binding site. In general, mutants with a Tm lower than that of mCRT(WT) in the unliganded (apo) state were stabilized to a greater degree upon sugar binding (L100A, VLI, F151A, H153A, V174 and F185A mutants), whereas a higher Tm in the apo state resulted in a slightly smaller window for stabilization upon sugar binding (L139A and VL) (Table 1). The mCRT(L179A) and mCRT(W183A) mutants yielded lower ΔTm values compared with mCRT(WT) and other mutants, which could result from distant conformational effects of these mutations upon the glycan binding site.

To investigate the chaperone activities of these mutants, LLO(d123), a truncated version of Listeriolysin O (LLO) lacking domain 4, was used as a non-glycosylated polypeptide substrate of calreticulin. LLO(d123) displays reduced kinetics of aggregation compared with the parent LLO construct as only 60 and 70% of LLO(d123) aggregates after 1 h of incubation at 37 °C, whereas full-length LLO is completely aggregated under these conditions (supplemental Fig. S2, left panels). mCRT(WT) can partially rescue aggregation of LLO(d123) at 37 °C in 0.5 mm CaCl2 when present in stoichiometric excess (1:4 or higher LLO(d123):mCRT), and several mutants were more active chaperones than mCRT(WT) at mCRT:substrate ratios of 1:4 and 1:8 (Fig. 1, C and D and supplemental Fig. S2, A–C). Consistent with previous findings (3, 7), calcium-depleting conditions induced the chaperone activities of mCRT(WT) and several mutants tested (Fig. 1D). mCRT(H153A), the mutant with lowest conformational stability (Table 1), was in fact a more active chaperone than mCRT(WT) and all other mutants at all stoichiometric ratios tested (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the conformationally stable mCRT(L139A) mutant displayed low chaperone activity resembling that of mCRT(WT) in 0.5 mm CaCl2 and impaired chaperone activity under calcium-depleting conditions (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S2). Results similar to these were obtained for mCRT(L139A) and mCRT(H153A) when full-length LLO was used as the substrate, which aggregates more rapidly than LLO(d123), requiring calcium-depleting conditions for visualization of the chaperone activity of mCRT(WT) at a 1:4 ratio (Ref. 7, Fig. 1E, and supplemental Fig. S2). Notably, when further mutations are made on the mCRT(L139A) background, the resulting double or triple mutants (VL or VLI) have similar or stronger polypeptide-specific chaperone activity toward LLO(d123) and LLO as does mCRT(WT) (Fig. 1, D and E). These findings indicate that leucine 139 does not represent a specific site for polypeptide binding, but rather it is a crucial determinant of conformational stability of mCRT, which in turn impacts its chaperone activity.

mCRT Mutants with Induced or Reduced Chaperone Activities Induce Cell-surface Expression of MHC Class I Molecules

Calreticulin-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (K42 cells) express reduced cell-surface MHC class I compared with their wild type counterparts (K41 cells), and cell-surface MHC class I levels can be restored by expression of mCRT(WT) in K42 cells (4). The abilities of all mutants discussed in Fig. 1 to restore MHC class I cell-surface expression were compared. When expressed at levels comparable with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 2A), all mutants restored cell-surface expression of H2-Kb (Fig. 2, B and C) and H2-Db (Fig. 2D) MHC class I allotypes to the level of cells expressing mCRT(WT) or mCRT(WT-FLAG), with the exception of the previously described glycan binding mutant mCRT(W302A) (7). In all cases, levels of surface MHC class I for cells expressing mCRT(WT) and mCRT(WT-FLAG) were significantly different from that of control vector-infected cells, which were normalized to a value of 1 for these analyses. Additionally, the chaperone-impaired mCRT(L139A) mutant does not impact the ability of mCRT to induce MHC class I cell-surface expression (see the Fig. 2 legend for statistical analysis). Furthermore, inducing chaperone activity in the context of mutants that are also able to interact with glycans does not enhance MHC class I surface expression (Fig. 2, B–D). Although the induction of MHC class I cell-surface expression in K42 cells by mCRT(WT) compared with control vector-infected cells was statistically significant in these assays (Fig. 2, B–D), the differences were small. Thus, additional assays were used with a select group of mutants to further address whether inducing or reducing the chaperone activity of calreticulin impacted other aspects of the MHC class I assembly pathway.

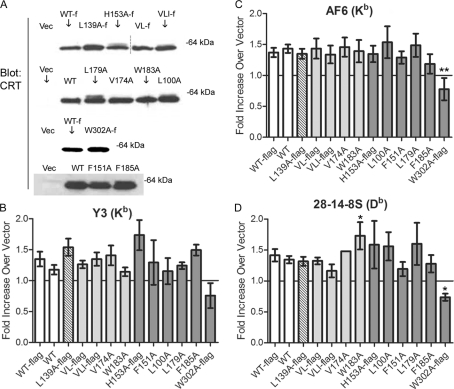

FIGURE 2.

mCRT mutants with induced or reduced chaperone activities are able to induce cell-surface expression of MHC class I molecules. A, cell lysates from K42 cells expressing each mCRT mutant or lacking mCRT expression (Vec) were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting analyses were undertaken for detection of mCRT. B–D, shown are flow cytometric analyses of cell-surface expression of MHC class I on K42 cells infected with retroviruses encoding the indicated mCRT constructs or control virus lacking CRT. The -fold induction of mean fluorescence by each mCRT construct relative to parallel infections with control virus is indicated. Y3 (anti-H2-Kb), AF6 (anti-H2-Kb), or 28–14-8S (anti-H2-Db) antibodies were used in the analyses as indicated. Data are averaged over at least two independent analyses from separate infections that had similar levels of calreticulin expression for the mutant proteins as for mCRT(WT), except for V174A in (D), which was measured once. Shading is added for ease of interpretation and indicate degree of chaperone ability based on assays in Fig. 1, C–E. White represents wild type. Dark gray represents mutants that had strongly induced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity. Light gray represents mutants that had similar or slightly induced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity relative to wild type. The L139A mutant (hashed) is the only mutant that displayed reduced chaperone activity relative to wild type. * and ** indicate statistical difference from the appropriate WT control with p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively. All p values were generated using a two-tailed, unpaired t test. W302A-FLAG is significantly different from WT-FLAG in C (p = 0.007) and D (p = 0.012) and shows the most statistical difference of all mutants from WT or WT-FLAG in B, with p = 0.074. W183A is significantly different from WT in D (p = 0.037) but not in B (p = 0.816) or C (p = 0.799). Neither H153A-FLAG nor L139A-FLAG was significantly different from WT-FLAG; in B, C, and D, respectively, p = 0.186, p = 0.892, p = 0.596 for H153A-FLAG versus WT-FLAG; p = 0.358, p = 0.860, p = 0.612 for L139A-FLAG versus WT-FLAG. Statistical analyses could not be performed on the single replicate of V174A in D. Surface MHC class I for WT, WT-FLAG, and L139A-FLAG-expressing cells are significantly different from vector (normalized to a value of 1 for each assay) when measured by all three antibodies (in B, C, and D, respectively, p = 0.039, p < 0.0001, p = 0.0001 for WT versus vector; p = 0.009, p = 0.0001, p = 0.0007 for WT-FLAG versus vector; p = 0.006, p = 0.004, p = 0.012, for L139A-FLAG versus vector). Dashed lines in panel A indicate lanes that were cut and pasted from the same blot to preserve the order of presentation of lanes. Some constructs contain a FLAG epitope tag inserted at the C terminus, before the KDEL retention sequence, and are indicated with “-f” or “-flag”.

mCRT Mutants with Induced or Reduced Chaperone Activities Can Restore Steady-state Levels of Tapasin and MHC Class I and Become Incorporated into the Peptide Loading Complex

We have previously shown that steady-state levels of MHC class I heavy chains as well as the assembly factor tapasin are low in cells lacking calreticulin expression or in cells expressing mCRT mutants that are non-functional in the context of MHC class I assembly (7). We analyzed the abilities of mCRT mutants to restore steady-state levels of tapasin and MHC class I heavy chains. The steady-state level of ERp57 is not decreased in cells lacking calreticulin and is in fact induced (Fig. 3A) (15), and thus, ERp57 serves as a loading control for comparisons of abilities of different calreticulin mutants to stabilize MHC class I heavy chains and tapasin. The two mutants that represent the extreme phenotypes of polypeptide-specific chaperone activity in vitro, mCRT(H153A) and mCRT(L139A), stabilized MHC class I heavy chain and tapasin steady-state levels, whereas glycan binding deficient mCRT(W302A) did not, as previously noted for the latter mutant (7) (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the polypeptide binding deficiency of the conformationally rigid mCRT(L139A) mutant does not impact its ability to stabilize tapasin and MHC class I heavy chains. We also analyzed MHC class I heavy chain and tapasin levels in cells expressing the remaining mCRT mutants. Although ERp57 was not analyzed in the context of all mutants, the use of multiple protein loads along with the corresponding control cells expressing wild type (positive control) or lacking calreticulin (negative control) allows for the conclusion that all mutants can restore steady-state levels of MHC class I heavy chains and tapasin to the level of mCRT(WT)-expressing cells (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

mCRT mutants with induced or reduced chaperone activities can restore steady-state levels of tapasin and MHC class I heavy chains and become incorporated into the peptide loading complex. A, cell lysates from K42 cells expressing the indicated mCRT mutant or lacking mCRT expression (Vec) were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting analyses were undertaken for detection of mCRT, tapasin, MHC class I heavy chain, and ERp57, as indicated. Steady-state levels of ERp57 were not reduced and may in fact be enhanced in calreticulin-deficient cells, with ERp57 blots thus serving as a loading control. The abilities of different calreticulin mutants to restore steady-state levels of MHC class I and tapasin were verified from at least two separate infections. Only mCRT(W302A) was impaired in its ability to rescue heavy chain and tapasin expression. MHC class I is occasionally observed as a doublet (indicated by arrows). NS indicates a nonspecific band. B, immunoprecipitations (IP) with anti-TAP1 of lysates from cells expressing the indicated mCRT constructs or control vector-infected (Vec) cells. Immunoblotting analyses were undertaken with antibodies directed against various PLC components. Data are representative of three independent analyses. No antibody (No Ab) controls were performed by incubating indicated lysates with beads in the absence of antibody, and the Ab lane in the TAP1 IP group indicates an IP control with buffer. Ab marks the position of the antibody heavy chain band. The left-most lane (WT lysate) marks the migration position of each immunoblotted protein (from cell lysates).

To further test the function of polypeptide binding on interactions within the PLC, the two mutants that represented the extreme phenotypes of thermostability and polypeptide-specific chaperone activity in vitro, mCRT(H153A) and mCRT(L139A), were next compared for their interactions with the PLC. mCRT(W302A) was also included in these analyses as a control for lack of PLC incorporation due to its glycan binding deficiency (7). In a TAP1 immunoprecipitation, although mCRT(W302A) association was not detectable as previously described (7), comparable levels of mCRT(WT), mCRT(L139A), and mCRT(H153A) were co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 3B, left panel, CRT blot). Thus, polypeptide binding efficiency does not appear to significantly impact the incorporation of mCRT into the PLC.

mCRT Mutants with Induced or Reduced Chaperone Activity Can Reduce the Kinetics of MHC Class I Export from the ER

Calreticulin functions in the retrieval of sub-optimally loaded MHC class I molecules from the cis-Golgi to the ER (4, 16), and thus, calreticulin deficiency enhances the rate of export of these MHC class I molecules from the ER. We wanted to compare abilities of calreticulin mutants with differential polypeptide binding abilities to reduce the rate of MHC class I trafficking in K42 cells. To do this, K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT), selected mutants, or no calreticulin were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine and chased with cold media for the indicated times. Calreticulin mutants selected were those with the highest (mCRT(L139A)) or lowest (mCRT(H153A)) conformational stabilities (Table 1), which also represented constructs with the lowest or highest chaperone activity, respectively (Fig. 1). mCRT(W302A), which was deficient in glycan binding and had induced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity relative to mCRT(WT) (7), was also included. Lysates from the relevant cells were immunoprecipitated for the MHC class I H2-Kb allotype. Immunoprecipitated MHC class I molecules were either left undigested or digested with endoglycosidase Hf (Endo Hf), separated by SDS-PAGE, imaged by autoradiography, and Endo Hf-resistant and -sensitive bands were quantified (Fig. 4A). Consistent with previous findings (4), MHC class I trafficking in calreticulin-deficient cells is accelerated compared with that in cells expressing mCRT(WT) (Fig. 4B). Additionally, MHC class I trafficking was accelerated in the context of mCRT(W302A), likely due to the glycan binding deficiency of this mutant (Fig. 4B), whereas the rates of class I trafficking in cells expressing mCRT(L139A) and mCRT(H153A) were similar to those of cells expressing mCRT(WT) (Fig. 4B). Similar results were observed for the trafficking of the MHC class I H2-Db allotype (data not shown).

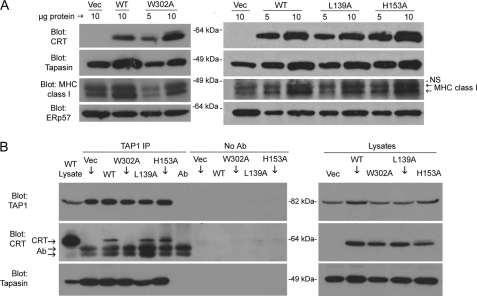

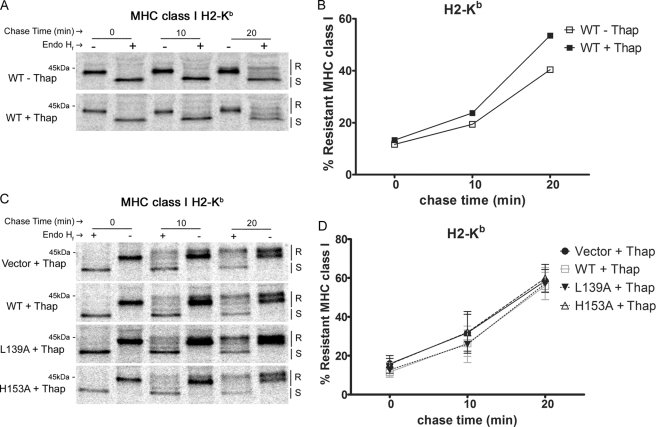

FIGURE 4.

mCRT mutants with induced or reduced chaperone activity can reduce the kinetics of MHC class I export from the ER. A, K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT), the indicated mutants, or no calreticulin (Vector) were metabolically labeled for 10 min and chased for indicated times. Proteins in lysates were immunoprecipitated with Y3 (anti H2-Kb) antibody, then digested with Endo Hf (+ lanes) or left undigested (− lanes) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging analyses. R and S indicate Endo Hf digestion-resistant and -sensitive bands, respectively. B, Endo Hf-resistant MHC class I heavy chain (HC) bands in the gels from A were quantified using ImageQuant and plotted as a percentage of total HC. Data in B are averaged from two-three independent analyses.

In Thapsigargin-treated Cells, Calreticulin Is Unable to Reduce the Kinetics of MHC Class I Export from the ER

The above findings showed that inducing or reducing the polypeptide binding activity of calreticulin mutants did not significantly impact the ability of calreticulin to promote MHC class I assembly under normal conditions, as assessed by a number of different assays (Figs. 2–4). We have previously shown that ER stress induces polypeptide binding conformations of calreticulin, enhancing its binding to MHC class I heavy chains in vitro and in cells (3). Based on these findings, we expected that conditions that induce ER stress might enhance ER retention of MHC class I heavy chains and reduce the kinetics of MHC class I trafficking, particularly in cells expressing mutant calreticulin proteins with induced chaperone activities. To examine these possibilities, cells were treated for 5 h with thapsigargin, a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump inhibitor, before the metabolic labeling of the cells. During these short time points of drug treatment, the majority of cells were viable, as assessed by staining with annexin V and 7-aminoactinomysin D (data not shown). Surprisingly, in the context of mCRT(WT), we found that MHC class I molecules were trafficked more rapidly in thapsigargin-treated cells compared with untreated cells (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, after thapsigargin treatment, MHC class I trafficking rates in cells expressing mCRT(WT) or any of the tested mutants approached the rates observed in the calreticulin-deficient cells (Fig. 5, C and D). This was in contrast to the results obtained in untreated cells (Fig. 4, A and B), where mCRT(WT) and all mutants except mCRT(W302A) were able to reduce the kinetics of MHC class I trafficking. These findings suggested an impaired ability of calreticulin to mediate MHC class I ER retention in thapsigargin-treated cells.

FIGURE 5.

In thapsigargin-treated cells, calreticulin is unable to reduce the kinetics of MHC class I export from the ER. A and C, K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT), the indicated mutants, or no calreticulin (Vec) were metabolically labeled for 10 min and chased for indicated times. Proteins in lysates were immunoprecipitated with Y3 (anti H2-Kb) antibody, then digested with Endo Hf (+ lanes) or left undigested (− lanes) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging analyses. Cells were untreated (− Thap) or treated with thapsigargin (+ Thap) as indicated. R and S indicate Endo Hf digestion-resistant and -sensitive bands, respectively. B and D, Endo Hf-resistant MHC class I heavy chain bands in the gels from A and C were quantified using ImageQuant and plotted as a percentage of total heavy chain. Data in B are based on a single analysis, and data in D are averaged from three independent experiments.

Thapsigargin Treatment of Cells Reduces MHC Class I Cell-surface Expression and Induces Calreticulin Cell-surface Expression

Correlating with the accelerated trafficking rates of H2-Kb molecules in thapsigargin-treated cells compared with untreated cells (Fig. 5A), we found that levels of cell-surface MHC class I (H2-Kb) were reduced in thapsigargin-treated cells compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6, A and B). The extent of thapsigargin-mediated reduction in cell-surface MHC class I was less pronounced in calreticulin-deficient K42 cells compared with the counterpart wild type K41 cells (Fig. 6, A and B), indicating that a loss of calreticulin function may be partially responsible for the failed ER retention of MHC class I molecules in the context of thapsigargin-treated cells.

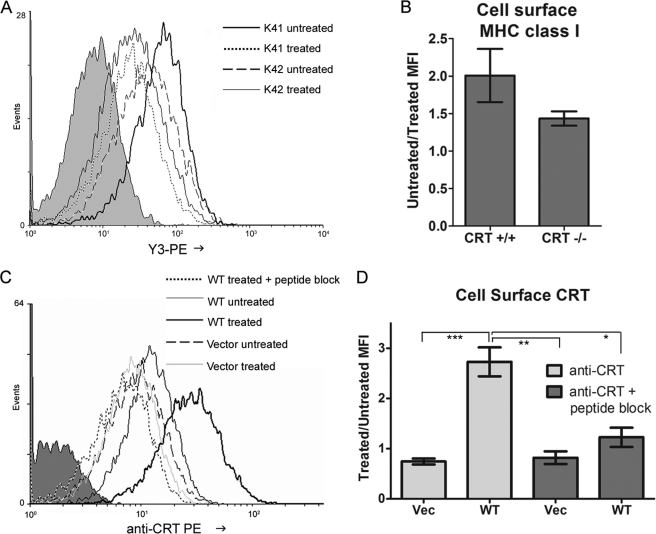

FIGURE 6.

Thapsigargin treatment reduces cell-surface MHC class I and induces cell-surface calreticulin expression. A and B, representative flow cytometric analyses show staining of cell-surface MHC class I with the mouse MHC class I (H2-Kb-specific) antibody Y3 in thapsigargin-treated cells compared with untreated cells using K41 (CRT +/+) or K42 (CRT −/−) cells. Data shown in B are averaged over three independent experiments. PE, R-Phycoerythrin. C and D, representative flow cytometric analyses show cell-surface calreticulin induction by thapsigargin treatment. K42 cells infected with retroviruses encoding mCRT(WT) (WT) or control virus (Vector/Vec) were used. Shaded histograms indicate cells stained only with secondary antibody. Detection of cell-surface CRT is inhibited by preincubating the antibody with its peptide immunogen (peptide block). Data in D are averaged over three-four experiments. MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01. *** indicates p < 0.001. All p values were generated using a two-tailed, unpaired t test.

Thapsigargin treatment of cells has been reported to deplete intracellular calreticulin (17) and induce cell-surface calreticulin expression in some studies (18). We examined the possibility of cell-surface calreticulin exposure in murine fibroblasts after thapsigargin treatment. K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT) or no calreticulin (vector) were treated for 5 h with thapsigargin, a time point shown to induce ER chaperone secretion in cells treated with calcium ionophores (17). We found that thapsigargin treatment did indeed induce strong cell-surface exposure of mCRT(WT) in these cells (Fig. 6, C and D). Specificity of the signal was established using counterpart cells infected with a control virus lacking calreticulin (Fig. 6, C and D, Vec), and the surface calreticulin signal was inhibited by preincubating the anti-CRT antibody with a calreticulin-derived peptide against which the antibody was raised (Fig. 6, C and D, peptide block). Thus, coincident with accelerated MHC class I trafficking and reduced cell-surface MHC class I expression in thapsigargin-treated cells, cell-surface expression of calreticulin was induced by thapsigargin treatment.

Polypeptide-based Interactions Contribute to Calreticulin Binding to the Cell Surface in ER calcium-depleted Fibroblasts

This finding that ER retention of mCRT is compromised in thapsigargin-treated cells coincident with accelerated intracellular trafficking of a substrate protein raised the possibility that a substrate such as MHC class I could mediate the export and/or cell-surface expression of calreticulin in thapsigargin-treated cells. If calreticulin is released into the Golgi complex with substrates, it is possible that cell-surface expression of calreticulin is mediated through its substrate binding sites. Glycan-mediated binding of calreticulin to substrates could allow for the co-trafficking of substrate-calreticulin complexes through the secretory pathway, preventing Golgi glycosidase access to substrate glycans, as has been suggested for calnexin trafficking in thymocytes (19). Alternatively, generic polypeptide binding sites of calreticulin could become relevant to calreticulin-substrate interactions upon their co-trafficking into the Golgi and cleavage of calreticulin-specific glycans.

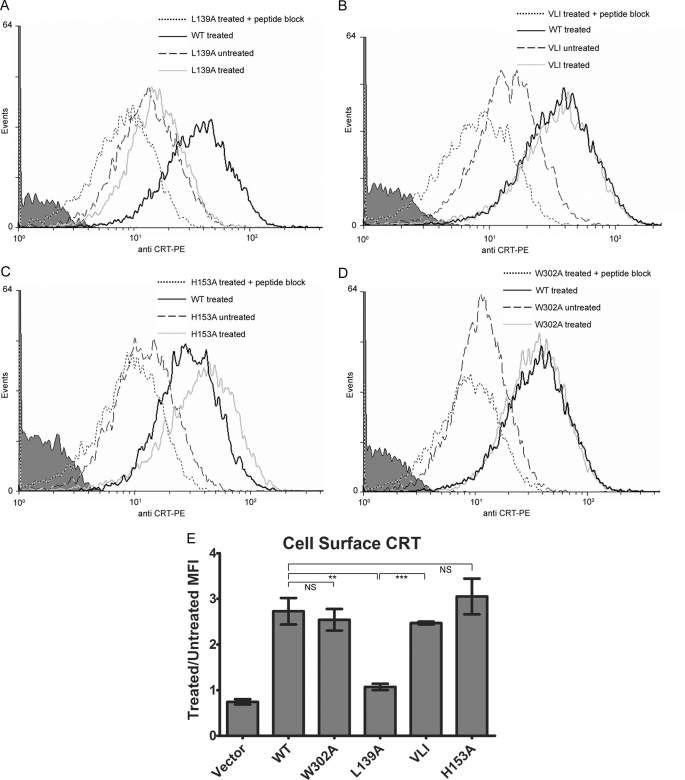

We examined the possibility of calreticulin binding to cell-surface substrates via either its glycan or generic polypeptide binding sites by comparing cell-surface expression and secretion of select calreticulin mutants in thapsigargin-treated cells. The mCRT mutants tested were again those with the lowest or highest polypeptide-specific chaperone activities (mCRT(L139A) and (mCRT(H153A)) and the glycan binding-deficient mCRT(W302A) mutant as well as the mCRT(VLI) mutant, which was included to test the site specificity versus conformational effects of mCRT(L139A). We found that, compared with mCRT(WT), the conformationally stable mCRT(L139A) was strongly impaired in its cell-surface expression after thapsigargin treatment of cells (Fig. 7, A and E). Surface expression of the triple mutant mCRT(VLI) was significantly enhanced relative to mCRT(L139A), indicating that the conformational stability of mCRT(L139A), rather than the direct involvement of leucine 139 in cell-surface substrate binding, contributes to the low cell-surface expression of mCRT(L139A) in thapsigargin-treated cells (Fig. 7, B and E). mCRT(H153A) was found at higher levels on the cell surface than mCRT(WT) within individual experimental comparisons undertaken (for example, that shown in Fig. 7C), although the difference did not achieve significance when averaged values were compiled (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

Polypeptide-based interactions contribute to calreticulin binding to the cell surface of ER calcium-depleted fibroblasts. A–D, representative histograms show thapsigargin-induced cell-surface calreticulin in K42 cells expressing mCRT(WT) or indicated mutants. Analyses were performed as described in Fig. 6C. E, results are averaged across two-four independent analyses for each mutant. MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity. NS indicates not significant. ** indicates p < 0.01. *** indicates p < 0.001. All p values were generated using a two-tailed, unpaired t test. PE, R-Phycoerythrin.

We would generally expect that trafficking of substrate proteins through the Golgi to the cell surface would result in modifications of the classical monoglucosylated ER glycan substrates of calreticulin. However, it is possible that co-trafficking of calreticulin-substrate complexes through the Golgi could protect monoglucosylated glycans from processing in the Golgi and result in cell-surface expression of glycan substrates of calreticulin. As noted above, this model has previously been proposed for binding of the calreticulin homolog, calnexin, to the thymocyte cell surface (19). It appears, however, that classical ER glycans are not relevant to the observed cell-surface interactions of calreticulin after ER calcium depletion, as cell-surface expression of mCRT(W302A) mutant was comparable with that of mCRT(WT) (Fig. 7, D and E). Together, these findings indicate that mCRT cell-surface expression in thapsigargin-treated cells is dependent on its polypeptide-receptive conformation (Fig. 7E).

Calreticulin Conformations Impact Its Secretion from Thapsigargin-treated Cells

MHC class I trafficking was accelerated by thapsigargin treatment in the context of all tested calreticulin mutants, yet mCRT(L139A) was not observable at the cell surface (Fig. 7). This raised the possibility that the impaired polypeptide-specific chaperone activity of mCRT(L139A) resulted in its secretion rather than retention at the cell surface. To further examine this possibility, supernatants and lysates of untreated and thapsigargin-treated versions of K42 cells expressing the different mCRT constructs were compared for their calreticulin content and conformational signatures (Fig. 8).

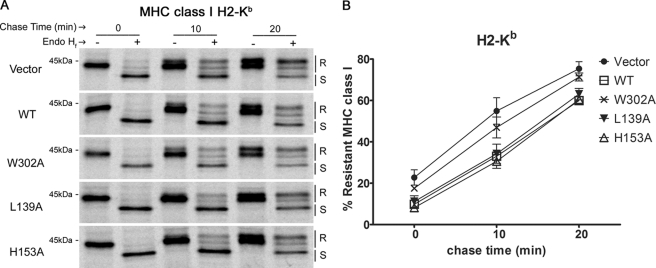

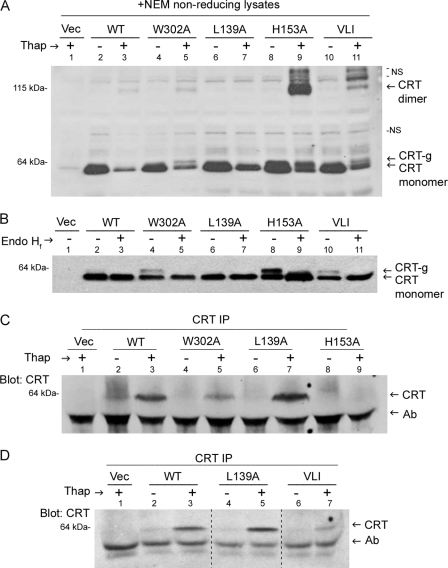

FIGURE 8.

Calreticulin conformations impact its secretion from thapsigargin-treated cells. A, immunoblotting analysis of 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) lysates from K42 cells expressing indicated mCRT constructs or control cells lacking calreticulin (Vec). Untreated cells (−) or cells treated for 5 h with 5 μm thapsigargin (Thap, +) were analyzed under non-reducing (−DTT) conditions. Results are representative of two independent analyses. NS denotes nonspecific bands. B, reducing lysates from indicated thapsigargin-treated cells were left undigested (−) or digested with endoglycosidase Hf (+). Results are representative of two independent analyses. C and D, shown is an immunoblotting analysis for detection of mCRT in an anti-calreticulin-based immunoprecipitation (IP) of supernatants from the indicated untreated cells (−) or cells treated with 5 μm thapsigargin for 5 h (+). K42 cells lacking calreticulin (Vec) or cells expressing mCRT(WT) or the indicated mutants were used. Results are representative of two-four independent analyses. Ab denotes migration position of antibody heavy chain band. Dashed lines in panel D indicate lanes that were cut and pasted from the same blot to preserve the order of presentation of lanes.

Upon thapsigargin treatment of cells, a dimeric form of calreticulin is induced, as previously described (3). The calreticulin dimer is disulfide-linked (3) and, therefore, visualized when samples are separated by non-reducing SDS-PAGE before immunoblotting analyses (Fig. 8A, CRT dimer). Calreticulin dimers were overrepresented in thapsigargin-treated cells expressing mutants with reduced thermostability, particularly mCRT(H153A), as also observed with the purified protein in vitro (Fig. 8A, lane 9, and Fig. 1B, WT versus H153A panels, 37 °C lanes). On the other hand, dimers were essentially undetectable with mCRT(L139A) (Fig. 8A, lane 7). Thus, reduced thermostability of calreticulin correlates with enhanced dimer formation.

Notably, the strong overrepresentation of dimeric calreticulin with mCRT(H153A) compared with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 8A, lanes 3 and 9) is accompanied by only a small induction in cell-surface expression of mCRT(H153A) relative to mCRT(WT) (Fig. 7, C and E). Consistent with these findings, we have previously shown that calreticulin dimerization per se is not required for polypeptide substrate binding in vitro (3).

Upon thapsigargin treatment of the cells, a slower migrating species of calreticulin monomers, previously suggested to be a glycosylated form of calreticulin, is also induced as previously described (3) (Fig. 8, A and B, CRT-g). CRT-g was Endo Hf-sensitive (Fig. 8B), consistent with the possibility that it is an ER-retained glycosylated form of calreticulin, although more detailed analyses will be needed to confirm this possibility. It is noteworthy that CRT-g is also more strongly induced in the context of mutants with reduced thermostability (mCRT(H153A), mCRT(W302A), and mCRT(VLI)) compared with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 8B). Based on the recent crystal structure analysis of a truncated form of mCRT lacking the C-terminal acidic and P domains (20), the single N-linked glycosylation site present within the C-terminal helix of calreticulin (Asn-327 in mature protein numbering) is predicted to be surface-exposed. The finding that calreticulin is largely non-glycosylated in murine fibroblasts under normal conditions suggests that in the context of the full-length protein, this glycosylation site is in fact buried, likely by interactions with the acidic domain, and rendered non-accessible. Based on the data shown in Fig. 8B, it is reasonable to speculate that under calcium-depleting conditions, the glycosylation site could become exposed to an extent that is dependent upon the degree of conformational flexibility of particular calreticulin construct used.

Calreticulin was not detectable in cell supernatants by direct immunoblotting (data not shown). Thus, a calreticulin immunoprecipitation was performed on supernatants of untreated or thapsigargin-treated cells expressing relevant mCRT constructs or from cells lacking calreticulin expression. We found that thapsigargin treatment did induce calreticulin secretion, and recovery of the conformationally stable mCRT(L139A) from supernatants was in fact enhanced relative to mCRT(WT), whereas mCRT(H153A) was barely detectable and mCRT(W302A) showed reduced recovery relative to mCRT(WT) (Fig. 8C, lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9). Recovery of mCRT(VLI) was also reduced relative to mCRT(L139A) and mCRT(WT) (Fig. 8D, lanes 3, 5, and 7). Thus, the mutant mCRT(L139A) that displays reduced capacity to bind polypeptide substrates and is impaired in its surface expression on thapsigargin-treated cells is released into cell supernatants at higher levels than mCRT(WT) and other mutants. Lower recoveries of the conformationally labile mCRT mutants relative to mCRT(WT) may reflect reduced stabilities of the mutants in cell supernatants or their enhanced intracellular/surface retention. Putative glycosylation of calreticulin appears not to be required for secretion, as suggested by the absence of glycosylated mCRT(L139A) after thapsigargin treatment and by the Endo Hf sensitivity of all glycosylated calreticulin species in thapsigargin-treated cells (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

Calreticulin can suppress the in vitro aggregation of a number of different misfolded non-glycosylated polypeptide substrates in a substrate-nonspecific manner (2, 3), indicating the presence of one or more generic polypeptide binding site(s) on calreticulin. Previous studies have shown that exposure of such polypeptide binding sites is induced by conditions of heat shock and calcium depletion (3). Several calreticulin truncations and mutations also induce the exposure of generic polypeptide binding sites on calreticulin at 37 °C in the presence of calcium (Fig. 1 and Ref. 7). As we show here, the induction of chaperone activities of calreticulin mutants generally correlates with reduced thermostabilities of mutant proteins as assessed by binding to a hydrophobic dye, suggesting that enhanced exposure of hydrophobic surfaces in the mutant proteins is responsible for the chaperone hyperactivity phenotype. Among those tested, the only mutation that significantly enhanced calreticulin thermostability was mCRT(L139A) (Table 1). The mCRT(L139A) mutant also displayed inhibited induction of the conformation relevant to the polypeptide-specific chaperone activity of calreticulin (Fig. 1, D and E) and offered a valuable tool to test the relevance of calreticulin generic polypeptide binding sites to its protein folding functions under normal and ER stress conditions. It is important to re-emphasize that leucine 139 does not represent a specific site for polypeptide binding. Rather, it is a crucial determinant of conformational stability of mCRT, which in turn impacts chaperone activity. Precise mechanisms underlying the strong effects of leucine 139 upon calreticulin conformation remain unclear.

Previously, a role for calreticulin polypeptide binding function has been suggested in the context of the PLC and MHC class I assembly (21). However, we demonstrate here using mCRT mutants with induced or reduced polypeptide-specific chaperone activity that generic polypeptide binding sites of mCRT do not significantly impact the MHC class I assembly pathway (Figs. 2–4). These findings are in agreement with our previous report that glycan, ERp57, and other specific associations mediated by calreticulin are important for its interactions with PLC components and/or a subsequent step of the assembly pathway (7). However, polypeptide-based, rather than glycan-based interactions, contributed to the cell-surface expression of mCRT in thapsigargin-treated cells (Fig. 7). It is possible that glycan-based binding could dominate the intracellular interactions mediated by calreticulin, rendering the impacts of polypeptide-based binding difficult to detect. However, as the classical glycan substrates of calreticulin are modified during transit through the secretory pathway, polypeptide-based binding interactions with substrates could persist and contribute to the cell-surface expression of calreticulin in complex with a membrane-linked substrate.

The question of how calreticulin escapes from the ER in the context of thapsigargin treatment remains to be further investigated. One possibility is that perturbation of ER calcium causes disorder in the ER protein gel/matrix resulting in broad protein leakage (suggested in Ref. 17). In several studies, ER calcium depletion has been shown to have major effects on the organization of the ER and the function of the secretory pathway. For example, the addition of the calcium ionophore ionomycin or thapsigargin to rat basophilic leukemia cells as well as to 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells was shown to induce fragmentation of the ER, resulting in a marked decrease in the rate of diffusion observed for the contents of this organelle (22). Such a restriction on the movement dynamics of proteins within the ER may trap certain proteins in budding vesicles that may otherwise have been excluded. Other studies have shown that the depletion of ER calcium by the calcium ionophores ionomycin and A23187 as well as by thapsigargin in 3T3 mouse fibroblasts and human hepatoma HepG2 cells decreases the rate of secretion and maturation of some proteins while leaving others relatively unaffected (23, 24). It appears that the mechanisms controlling protein quality control, retention, and secretion under calcium-depletion conditions are complex and potentially different for different proteins.

Because calreticulin is a unique protein that specifically functions as a calcium buffer in the ER (25), the effect of calcium depletion on its structure and retention may also be unique. From this perspective, another potential explanation for secretion of calreticulin under conditions of low ER calcium is that a conformational change involving the high capacity calcium coordinating C-terminal domain of calreticulin masks its KDEL retention sequence in calcium-depleting conditions, preventing retention of calreticulin through the KDEL receptor. It has also been shown that the acidic domain near the C terminus of calreticulin is partly responsible for the ER retention of calreticulin (26), and thus, disruption of the conformation of this domain could reduce the effectiveness of the retention mechanism.

A number of studies have reported cell-surface expression of calreticulin in different cell types, and a number of functions are ascribed to cell-surface calreticulin (for review, see Refs. 27 and 28). In the context of tumor cells, cell-surface calreticulin induced by anthracyclins is correlated with immunogenicity of drug-treated cells (29). Anthracyclin-induced cell-surface calreticulin is suggested to be dependent on co-translocation with ERp57 (30, 31). However, ERp57 binding was not required for calreticulin cell-surface expression in thapsigargin-treated cells.3 It is possible that under some conditions ERp57 substrates rather than direct substrates of calreticulin mediate the cell-surface expression of calreticulin.

A recent report suggests that the apoptotic stress-induced exposure of surface calreticulin could occur through its association with phosphatidylserine as it “flips” to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during apoptosis (32). This association between negatively charged phosphatidylserine and the acidic calreticulin protein was shown to require calcium. At the time points used in our study, thapsigargin treatment did not induce a significant increase in phosphatidylserine exposure, as measured by annexin V positivity (data not shown), and surface calreticulin levels in Figs. 6 and 7 are reported only for cells that stained negatively for annexin V. Thus, a phosphatidylserine-mediated mechanism is not likely to explain the cell-surface exposure of calreticulin under conditions of thapsigargin treatment that were used in this study.

It remains to be established whether thapsigargin can induce cell-surface calreticulin in other cell types including tumor cells. The immunological impacts of cell-surface calreticulin in thapsigargin-treated cells also require further investigation, given that thapsigargin pro-drugs are currently in clinical trial (33). Nonetheless, with this work, the polypeptide-specific binding site(s) of calreticulin gains a newfound significance in the extracellular environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Natasha Del Cid for generating a truncated version of LLO (LLOd123), Sanjeeva Wijeyesakere, Ramkumar Nandkumar, and Kalpana Krishnaswamy (Metaome Science Informatics, Ltd.) for assistance with supplemental Table 1, and Rachael Sturtevant, Laura Weiser, and Ericca Stamper for early contributions to the project. We thank the University of Michigan Hybridoma core for antibody production and the University of Michigan DNA sequencing core for sequencing DNA constructs used. We are grateful to Drs. Marek Michalak and Tim Elliott for providing calreticulin-deficient K42 cells and to Drs. Ted Hansen and Jon Yewdell for antibodies used in these studies.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI066131 (to M. R.). This work was also supported by the University of Michigan Rheumatic Diseases Core Center.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables I and II and Figs. S1–S3.

L. R. Peters and M. Raghavan, unpublished observations.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- MHC

- major histocompatibility complex

- G1M3

- Glcα1–3Manα1–2Manα1–2Man

- K41

- wild type mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line

- K42

- calreticulin-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line

- LLO

- listeriolysin O

- LLO(d123)

- LLO lacking domain 4

- mCRT

- murine calreticulin

- mCRT(VLI)

- mCRT(V138A/L139A/I140A)

- PLC

- peptide loading complex

- Endo Hf

- endoglycosidase Hf.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ellgaard L., Helenius A. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saito Y., Ihara Y., Leach M. R., Cohen-Doyle M. F., Williams D. B. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6718–6729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rizvi S. M., Mancino L., Thammavongsa V., Cantley R. L., Raghavan M. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 913–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao B., Adhikari R., Howarth M., Nakamura K., Gold M. C., Hill A. B., Knee R., Michalak M., Elliott T. (2002) Immunity 16, 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raghavan M., Del Cid N., Rizvi S. M., Peters L. R. (2008) Trends Immunol. 29, 436–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peaper D. R., Cresswell P. (2008) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 343–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Del Cid N., Jeffery E., Rizvi S. M., Stamper E., Peters L. R., Brown W. C., Provoda C., Raghavan M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4520–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ireland B. S., Brockmeier U., Howe C. M., Elliott T., Williams D. B. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2413–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9. Chiu J., March P. E., Lee R., Tillett D. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mandal M., Mathew E., Provoda C., Dall-Lee K. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 372, 319–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lo M. C., Aulabaugh A., Jin G., Cowling R., Bard J., Malamas M., Ellestad G. (2004) Anal. Biochem. 332, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malawski G. A., Hillig R. C., Monteclaro F., Eberspaecher U., Schmitz A. A., Crusius K., Huber M., Egner U., Donner P., Müller-Tiemann B. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 2718–2728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leach M. R., Cohen-Doyle M. F., Thomas D. Y., Williams D. B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29686–29697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo L., Groenendyk J., Papp S., Dabrowska M., Knoblach B., Kay C., Parker J. M., Opas M., Michalak M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50645–50653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fu H., Liu C., Flutter B., Tao H., Gao B. (2009) Mol. Immunol. 46, 3198–3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Howe C., Garstka M., Al-Balushi M., Ghanem E., Antoniou A. N., Fritzsche S., Jankevicius G., Kontouli N., Schneeweiss C., Williams A., Elliott T., Springer S. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 3730–3744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Booth C., Koch G. L. (1989) Cell 59, 729–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tufi R., Panaretakis T., Bianchi K., Criollo A., Fazi B., Di Sano F., Tesniere A., Kepp O., Paterlini-Brechot P., Zitvogel L., Piacentini M., Szabadkai G., Kroemer G. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 274–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wiest D. L., Burgess W. H., McKean D., Kearse K. P., Singer A. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 3425–3433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kozlov G., Pocanschi C. L., Rosenauer A., Bastos-Aristizabal S., Gorelik A., Williams D. B., Gehring K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38612–38620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang Y., Kozlov G., Pocanschi C. L., Brockmeier U., Ireland B. S., Maattanen P., Howe C., Elliott T., Gehring K., Williams D. B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10160–10173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Subramanian K., Meyer T. (1997) Cell 89, 963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lodish H. F., Kong N. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10893–10899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lodish H. F., Kong N., Wikström L. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 12753–12760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakamura K., Zuppini A., Arnaudeau S., Lynch J., Ahsan I., Krause R., Papp S., De Smedt H., Parys J. B., Muller-Esterl W., Lew D. P., Krause K. H., Demaurex N., Opas M., Michalak M. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154, 961–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sönnichsen B., Füllekrug J., Nguyen Van P., Diekmann W., Robinson D. G., Mieskes G. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107, 2705–2717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gold L. I., Eggleton P., Sweetwyne M. T., Van Duyn L. B., Greives M. R., Naylor S. M., Michalak M., Murphy-Ullrich J. E. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 665–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kepp O., Tesniere A., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. (2009) Curr. Opin. Oncol. 21, 71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Obeid M., Tesniere A., Ghiringhelli F., Fimia G. M., Apetoh L., Perfettini J. L., Castedo M., Mignot G., Panaretakis T., Casares N., Métivier D., Larochette N., van Endert P., Ciccosanti F., Piacentini M., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Obeid M. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 2533–2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Panaretakis T., Joza N., Modjtahedi N., Tesniere A., Vitale I., Durchschlag M., Fimia G. M., Kepp O., Piacentini M., Froehlich K. U., van Endert P., Zitvogel L., Madeo F., Kroemer G. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 1499–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tarr J. M., Young P. J., Morse R., Shaw D. J., Haigh R., Petrov P. G., Johnson S. J., Winyard P. G., Eggleton P. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 401, 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwarze S. R., Lin E. W., Christian P. A., Gayheart D. T., Kyprianou N. (2008) Prostate 68, 1615–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pieper U., Eswar N., Braberg H., Madhusudhan M. S., Davis F. P., Stuart A. C., Mirkovic N., Rossi A., Marti-Renom M. A., Fiser A., Webb B., Greenblatt D., Huang C. C., Ferrin T. E., Sali A. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D217–D222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schrag J. D., Bergeron J. J., Li Y., Borisova S., Hahn M., Thomas D. Y., Cygler M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.