Abstract

In ion-coupled transport proteins, occupation of selective ion-binding sites is required to trigger conformational changes that lead to substrate translocation. Neurotransmitter transporters, targets of abused and therapeutic drugs, require Na+ and Cl− for function. We recently proposed a chloride-binding site in these proteins not present in Cl−-independent prokaryotic homologues. Here we describe conversion of the Cl−-independent prokaryotic tryptophan transporter TnaT to a fully functional Cl−-dependent form by a single point mutation, D268S. Mutations in TnaT-D268S, in wild type TnaT and in serotonin transporter provide direct evidence for the involvement of each of the proposed residues in Cl− coordination. In both SERT and TnaT-D268S, Cl− and Na+ mutually increased each other's potency, consistent with electrostatic interaction through adjacent binding sites. These studies establish the site where Cl− binds to trigger conformational change during neurotransmitter transport.

Keywords: Amino Acid Transport, Chloride Transport, Neurotransmitter Transport, Protein Structure, Serotonin Transporters, Chloride-binding Site, Ion-coupled Transport

Introduction

Transport proteins of the neurotransmitter sodium symporter (NSS, SLC6)3 family use transmembrane concentration gradients of monovalent ions as driving forces for substrate accumulation (1). The family includes transporters for the neurotransmitters serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)), dopamine, norepinephrine, glycine, and GABA (2). Several of these proteins are associated with psychiatric disorders including major depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia (3) and are targets for widely used antidepressants (4) and drugs of abuse (5). Most mammalian NSS proteins couple both Na+ and Cl− influx to substrate transport. In serotonin transporter (SERT), one Na+ and one Cl− ion are transported into the cell along with one molecule of serotonin as one K+ is transported out of the cell (6). The mechanisms of sodium and Cl− binding have been illuminated to some extent by studies arising from high resolution crystal structures of a prokaryotic transporter (7–10), although important molecular details of these processes remain to be determined.

Prokaryotic NSS proteins are amino acid transporters, and they have been valuable for understanding structure and mechanism in this family (11–20). Of the bacterial NSS members that have been cloned, only four have been characterized functionally: a tryptophan transporter (TnaT) from Symbiobacterium thermophilum (21), an amino acid transporter (LeuT) from Aquifex aeolicus (11), a tyrosine transporter (Tyt1) from Fusobacterium nucleatum (22), and an amino acid transporter (MhsT) from Bacillus halodurans (23). Like mammalian NSS proteins, these transporters require Na+ for function. However, they are completely independent of Cl− (11, 21–23). Consistent with this finding, the x-ray crystal structure of LeuT contains two binding sites for Na+: the “Na1” site adjacent to the bound substrate and the “Na2” site located 6 Å away from the substrate. However, no bound Cl− was found near the substrate-binding area (11).

Functional biochemical data and amino acid sequence homology suggest that the Na1 and Na2 sites are also present in SERT, dopamine transporter, and γ-aminobutyric acid transporter (GAT-1) at positions equivalent to those in LeuT (24–26). In 2007, we and others proposed a Cl− site in the neurotransmitter transporters based on computational analysis of the LeuT structure and sequence differences between prokaryotic Cl−-independent and mammalian Cl−-dependent transporters (8, 10). Two similar homology models of SERT and GAT-1 were presented along with biochemical evidence consistent with the general location of the Cl− ions in those structures. In both models, Cl− is coordinated by the side chains of Tyr-121, Ser-336, and Ser-372 (in transmembrane helices (TMs) 2, 6, and 7, SERT numbering). The models differed in that ours included Asn-368 (8) (TM7) and that of Zomot et al. (10) included Gln-332 (TM6). Cl− binding was proposed to provide a stabilizing countercharge for the adjacent Na1, with which it would share two coordinating residues (Ser-336 and Asn-368 in SERT) (8). In Cl−-independent prokaryotic transporters, this stabilizing role was proposed to be fulfilled by an ionized carboxyl group from the protein (Glu-290 in LeuT) (8, 10). All of the residues proposed to coordinate Cl− are contained within a four-helix bundle that has been proposed to rock back and forth relative to the rest of the protein during the transport cycle (16, 19).

The principal evidence for the location of the Cl− site came from SERT and GAT-1 mutants with glutamate or aspartate residues inserted near the putative Cl− site to resemble the corresponding region of LeuT (8, 10). These mutants typically had very low activity but did not require Cl− for transport. Mutants of LeuT and Tyt1 from which glutamate or aspartate residues had been removed to mimic the Cl− site of GAT-1 also had very low activity but were stimulated by Cl− (9, 10). The lack of robust transport activity in these mutants creates some uncertainty as to the identification of the residues that directly coordinate Cl−. For example, replacing an endogenous residue near the Cl− site with aspartate or glutamate could render SERT or GAT-1 insensitive to Cl− even if the original residue did not participate in Cl− coordination.

To address these issues, we have generated a fully functional Cl−-dependent mutant of the prototypical Cl−-independent bacterial transporter TnaT. Comparison of wild type TnaT with this mutant, together with further studies of SERT mutants, provides a more precise understanding of Cl− coordination and demonstrates the interdependence of Cl− and Na+ binding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

[3H]5-HT (27.1 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA), and [3H]Trp (20 Ci/mmol) was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Sulfo-NHS-SS Biotin and streptavidin-agarose resin were from Pierce, the anti-FLAG antibody was from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO), and the anti-Penta His was from Qiagen.

Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of both rat SERT and TnaT was performed with the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as described (8). TnaT mutants were constructed in the background of a TnaT cDNA carrying a His10 tag at the N terminus under the control of a constitutively active promoter extracted from the pUC18 vector (bases 2487–2616). All of the mutants were sequenced to verify accuracy.

5-HT Transport and Binding Assays

Transport measurements were performed as described previously (27). Before 5-HT uptake, the cells were rinsed four times with Cl−-free or Na+-free 5 mm potassium Pi buffer to remove Cl− or Na+ and then incubated in the indicated buffer containing [3H]5-HT for 10 min at 25 °C. To maintain isotonicity in transport buffers, with altered Na+ concentrations, NMDG was used to substitute Na+. For Cl− substitution the appropriate concentrations of either isethionate or sulfate were used instead of Cl− as indicated in the figure legends. When the divalent sulfate was used to replace Cl−, osmolarity was maintained by adding sucrose. Binding of [125I]β-CIT to HeLa cells expressing rSERT mutants was measured as described (27).

SERT Cell Surface Expression

Cell surface proteins were labeled at 4 °C with the membrane-impermeant biotinylation reagent sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce), as described previously (28).

Tryptophan Transport Assays

TnaT was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain CY15212 (mtr−, aroP−, and tnaB−), which lacks endogenous tryptophan transporters. CY15212 was transformed with pET-22 bearing the TnaT gene under control of the constitutive promoter from pUC18. Transport of l-[5-3H]tryptophan into intact cells was measured as follows: CY15212 cells transformed with pET-22/TnaT were grown overnight in LB broth in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C with shaking. Subsequently, the culture was diluted 100-fold in LB/ampicillin, and the incubation was continued until the culture reached an A600 of 0.8. Transport was performed on either Multiscreen-FB 96-well filtration plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) or with rapid filtration through individual 24-mm glass microfiber filters (Whatman, 934-AH) as described below.

For assays on Multiscreen-FB plates, 200 μl of cell suspension was added to each well (previously soaked in 0.1% polyethyleneimine). The cells were washed twice by filtration with 200 μl of M9 minimal medium (Na2HPO4, 88.4 mm; KH2PO4, 21.6 mm; NaCl, 8.4 mm; NH4Cl, 18.3 mm) including 0.4% glucose at room temperature, and transport was initiated by the addition of 200 μl of the same medium containing ∼200,000 cpm of radiolabeled tryptophan. The reaction was terminated by washing the wells three times with 200 μl of ice-cold M9. Sodium was substituted by NMDG and Cl− by gluconate as indicated in the figure legends. The filters were placed in Wallac 96-well Isoplates (part number 6005070) with 150 μl of Optifluor scintillation fluid and were allowed to soak for 2 h before counting.

For assays in individual 24-mm glass microfiber filters, 10 mm potassium Pi buffer, pH 7.4, supplemented with 110 mm NaCl, NMDG-Cl, sodium diatrizoate, or sodium sulfate was used instead of M9 medium. CY15212 cells were washed and resuspended in the indicated buffer, and 180 μl of the suspension was added to individual tubes. Transport was initiated by the addition of 20 μl of the same buffer containing ∼200,000 cpm of radiolabeled substrate. The reaction was terminated with 3 ml of ice-cold 10 mm potassium Pi, rapidly filtered through a glass microfiber filter and washed twice with 3 ml of ice-cold potassium Pi. The filters were then transferred to individual tubes with 3 ml of Optifluor scintillation fluid, incubated overnight, and counted.

Preparation of CY15212 Membranes to Determine Expression of TnaT

CY15212 cells expressing different TnaT mutants were grown overnight in LB in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C with shaking. The next morning the cultures were diluted 100-fold in LB/ampicillin, and the incubation was continued until it reached an A600 of 0.8. The cells were then collected by centrifugation (6,000 rpm, Eppendorf 5403, 16F6-38 rotor) and washed in washing buffer (150 mm NaCl, 15 mm Tris, pH 7.5). Subsequently, they were resuspended in sucrose buffer (30% w/v sucrose, 30 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA) with lysozyme at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/μl and incubated for 20 min under shaking in 37 °C. The cells were then disrupted by osmotic shock by adding distilled H2O containing DNase, 15 mm MgSO4, and protease inhibitor mixture followed by incubation at 37 °C for 20 min to digest DNA. The membranes were collected by centrifugation with a Sorvall F-20/Micro rotor at 18,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The membrane pellet was resuspended in 1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside and incubated for 2 h with shaking to solubilize proteins. Finally, the n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside concentration was decreased to 0.1% by the addition of 150 mm NaCl, 15 mm Tris, pH 7.5. Samples containing equal amounts of protein (determined by the BCA protein assay; Pierce) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an antibody against the poly-His tag.

Homology Modeling

A homology model of SERT was described previously (8), and the same template and alignment were used to construct a homology model of the D268S mutant of TnaT with Cl− bound. Modeler 9v5 (29) was used to construct 800 different models of Tnat-D268S, and the model with the smallest probability density function score was subjected to 400 steps of steepest descents energy minimization with the Charmm27 force field implemented in Charmm v34a2 (30).

RESULTS

The Role of Tyr-121 and Ser-336 Side Chains in Chloride Binding to SERT

Our previous studies on Cl− binding by SERT suggested that the Cl− ion is coordinated by the side chain of Ser-372 and near Asn-368 (8). Homology models of the site predict that Cl− is also coordinated by the side chains of Tyr-121 and Ser-336 (Fig. 1A). To completely characterize the site biochemically and to verify the involvement of each position, we substituted candidate residues with an aliphatic amino acid. Our expectation was that such a substitution would weaken Cl− coordination and increase Km for Cl−. Moreover, we extended our previous studies by mutating additional residues to aspartate or glutamate to evaluate their proximity to the Cl− site. Based on previous observations (8, 10), we expected that carboxyl groups on side chains close to the Cl− site would substitute for the negatively charged Cl− ion and lead to Cl− independent transport, albeit with reduced activity.

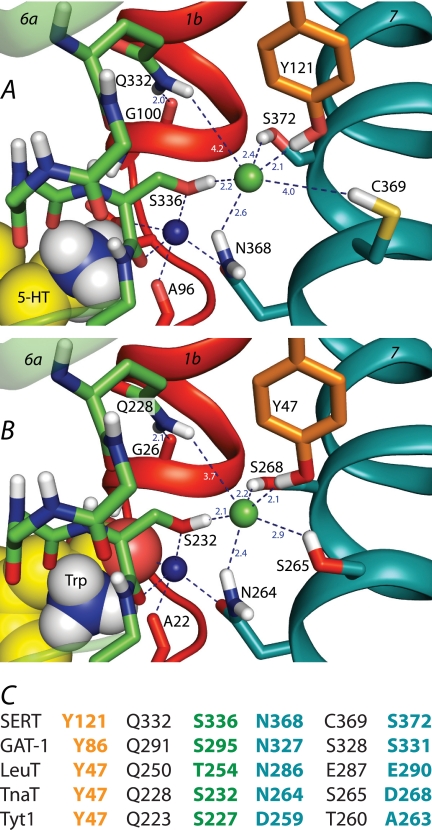

FIGURE 1.

A and B, the chloride-binding site in homology models of SERT (A) and of the D268S mutant of TnaT (B). TM helices 1 (red), 6 (green), and 7 (teal) are shown as ribbons, whereas side chains of selected residues are shown as sticks. The Cl− (green) and Na1 sodium (dark blue) ions are shown as spheres, as is the serotonin (A) or tryptophan (B) ligand. Relevant interactions or distances are indicated using dashed lines. C, comparison of candidate Cl−-binding site residues in mammalian transporters SERT and GAT-1 with the corresponding residues in bacterial NSS transporters LeuT, TnaT, and Tyt1. Cl−-binding site residues are shown in bold and color-coded by transmembrane helix (orange, TM2; green, TM6; teal, TM7).

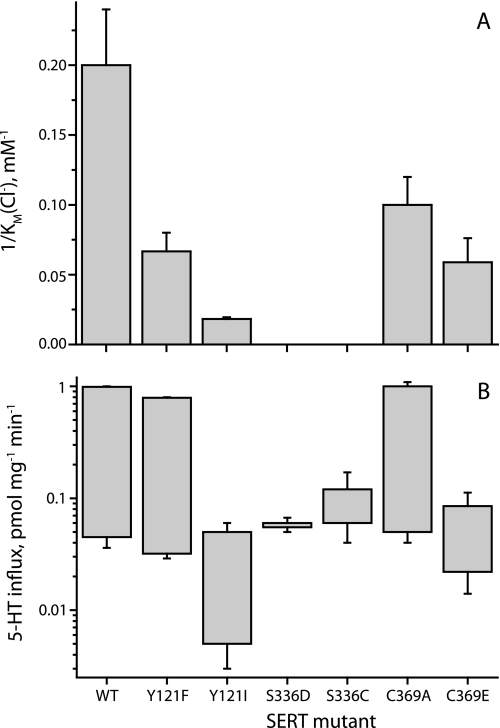

Mutagenesis at Tyr-121 provided support for the prediction that this residue participates in Cl− coordination. Conservative substitution of tyrosine with phenylalanine led to a 3-fold increase in the Km for Cl− relative to wild type rSERT, suggesting weaker coordination of the ion (Fig. 2A and Table 1). Y121F had high transport activity (Fig. 2B and Table 1), normal surface expression (supplemental Fig. S1) and bound the cocaine analog β-CIT as avidly as wild type rSERT, indicating correct protein folding (Table 1). More importantly, replacement with isoleucine, which is expected to interact unfavorably with Cl−, led to an 11-fold increase in the Km for Cl−. Substitution of Tyr-121 with glutamate resulted in low surface expression and activity (supplemental Fig. S1 and Table 1) and was not investigated further.

FIGURE 2.

Chloride dependence of SERT mutants. HeLa cells expressing wild type SERT or mutants Y121F, Y121I, S336D, S336C, C369A, and C369E were assayed for 5-HT influx for 10 min over a concentration range of Cl− (0–150 mm) using isethionate to replace Cl−. A, Km values for Cl− were calculated for each mutant and plotted as the reciprocal so that higher Cl− potency results in a taller bar. B, 5-HT influx at zero and 100 mm Cl− were plotted as floating bars, where the lower end of each bar represents the rate at 0 Cl−, and the higher end represents 150 mm Cl−. In this log plot, the length of the bar represents the degree of stimulation by Cl−. Each value represents the mean and S.E. of three to five experiments (corresponding values in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Initial rates of transport measured in HeLa cells

The initial rates of transport (10 min) were measured in HeLa cells expressing the wild type or indicated mutants as described under “Experimental Procedures” and expressed in terms of total cell protein. The percentage of activity at zero Cl− was calculated relative to that at maximal Cl− (100 mm). β-CIT binding was measured in similar cells. The Km for Cl− was calculated for functional Cl−-dependent mutants using a concentration range of Cl− and isethionate as a replacement. Each value represents the mean and S.E. of three to five independent experiments for the Km measurements and two to four independent experiments for the transport or binding activity measurements. Each experiment was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

| rSERT | 5-HT influx |

β-CIT binding | Km for Cl− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mm [Cl−] | 100 mm [Cl−] | |||

| pmol/mg/min | % of wild type | mm | ||

| Wild type | 0.045 ± 0.009 | 0.99 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 |

| S336D | 0.055 ± 0.005 | 0.06 ± 0.007 | 30 ± 3 | |

| S336E | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.009 ± 0.003 | 12 ± 1 | |

| S336V | 0.004 ± 1E-3 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 49 ± 2 | |

| S336A | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.03 ± 0.002 | 87 ± 2 | |

| S336C | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 93 ± 3 | |

| Y121F | 0.032 ± 0.003 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 93 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 |

| Y121I | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 38 ± 3 | 55 ± 4 |

| Y121L | 0.007 ± 0.003 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 49 ± 1 | |

| Y121E | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 17 ± 2 | |

| N368A | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.08 ± 0.007 | ||

| C369D | 0.021 ± 0.004 | 0.05 ± 0.001 | 14 ± 2 | |

| C369E | 0.022 ± 0.008 | 0.085 ± 0.027 | 54 ± 7 | 17 ± 5 |

| C369A | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 1 ± 0.06 | 100 ± 6 | 10 ± 2 |

| C369S | 0.1 ± 0.011 | 1.34 ± 0.08 | 96 ± 10 | 9 ± 2 |

| Q332E | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 98 ± 6 | |

| Q332L | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.027 ± 0.002 | 100 ± 2 | |

| Q332V | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 0.069 ± 0.020 | 88 ± 6 | |

| Q332C | 0.015 ± 0.003 | 0.109 ± 0.04 | 95 ± 7 | 42 ± 7 |

| Q332N | 0.002 ± 0.000 | 0.011 ± 0.002 | ||

In our analysis, we used Km values for Na+ and Cl− to estimate ion affinities. Although Km is influenced by kinetic parameters in addition to binding affinity, the dissociation constants for Na+ and Cl− are too high to measure directly. Consequently, we make the simplifying assumption that the primary effect of mutation on Km resulted from changes in ion affinity.

We were able to introduce aspartate in place of Ser-336 in TM6. Like the previously proposed Cl− binding residues Ser-372 and Asn-368 (8), a negative charge at Ser-336 prevented Cl− from stimulating 5-HT uptake (Fig. 2B and Table 1). The resulting transport activity of S336D was only 6% of wild type in the presence of 100 mm Cl− (Fig. 2B and Table 1), but this is characteristic of mutants with carboxylic side chains introduced near the proposed Cl−-binding site of SERT or GAT-1 (8, 10). As with previously described mutants, the low activity could not be attributed to decreased surface expression (supplemental Fig. S1), although S336D also had low β-CIT binding activity (Table 1). When we replaced Ser-336 with the aliphatic residues valine or alanine, transport activity was almost undetectable (Table 1). Decreased transport was not a result of low surface expression (supplemental Fig. S1) or improper protein folding because binding of β-CIT was 87% of wild type in S336A and 49% of wild type in S336V (Table 1). When cysteine replaced Ser-336, 5-HT transport was only moderately responsive to Cl−, with 50% of maximal activity at zero Cl− (Fig. 2B and Table 1). The sensitivity of SERT to mutation at Ser-336 might be explained by the fact that the corresponding residue in LeuT (Thr-254) interacts directly with bound Na1 (11), and thus substitutions at this position in SERT might disrupt the structure of both Na+ and Cl− sites.

Cys-369 and Gln-332 Do Not Play a Major Role in Chloride Binding to SERT

In addition to the four residues previously proposed to form the Cl− site in SERT (8) and GAT-1 (10), Zomot et al. (10) identified Cys-369 as also being near the modeled Cl− ion (10). In GAT-1, introduction of a negatively charged residue at the equivalent of SERT Cys-369 (Ser-328 in GAT-1; see Fig. 1C) reduced, although it did not completely abolish, the Cl− dependence of transport (10). However, these effects do not discriminate between direct coordination of Cl− by that residue or simply close proximity of the ionizable side chain to the binding site.

To investigate what role the side chains of SERT Cys-369 and Gln-332 play in Cl− coordination, we mutated these positions in SERT to both carboxylic and aliphatic residues. Mutation of SERT Cys-369 to glutamate, aspartate, alanine, or serine did not eliminate the Cl− dependence of transport (Fig. 2B and Table 1). With either alanine or glutamate replacing Cys-369, the Km for Cl− was modestly elevated compared with that of wild type rSERT (Fig. 2A and Table 1). These results indicate that the side chain of the cysteine is unlikely to contribute strongly to direct Cl− coordination in SERT, consistent with the prediction from a homology model of SERT, in which the distance between the ion and the side chain sulfur atom of Cys-369 is ∼4 Å (Fig. 1A). We considered the possibility that a small, indirect effect on Cl− binding upon mutation at this site might result from stabilizing interactions between the Cys-369 side chain and the phenolic oxygen of Tyr-121, which in turn coordinates the ion (Fig. 1A). However, in Y121F, which lacks this oxygen atom, mutation of Cys-369 to Ala had essentially the same effect as in wild type SERT (data not shown), rendering this indirect stabilizing effect unlikely.

Gln-332 is strictly conserved in all members of NSS and is irreplaceable in GAT-1, suggesting an important functional role (31). This residue was proposed by Zomot et al. (10) to coordinate Cl−. Based on the predicted distance between Gln-332 and the bound Cl− (>4 Å), it seems unlikely that Gln-332 could directly coordinate the Cl− ion. We tested a number of mutations at this position and found measurable transport activity in only one mutant, Q332C (∼10% of wild type; Table 1). 5-HT transport by Q332C was stimulated by Cl−, although it had low activity and an elevated Km for Cl− (Table 1). More information on the role of this residue was obtained from analysis of its function in TnaT (see below).

An Artificial Chloride-binding Site in TnaT

Prokaryotic members of the NSS family do not require Cl− for substrate transport (11, 21–23). Nevertheless, most of the residues predicted to coordinate Cl− are conserved or conservatively substituted between SERT, GAT-1, LeuT, and TnaT (8) (Fig. 1C). An exception is the position corresponding to Ser-372 in SERT, which is serine in most Cl−-dependent transporters but is aspartate in TnaT (Asp-268) or glutamate in LeuT (Glu-290). We and others previously proposed that in the Cl−-independent NSS transporters, a fixed negative charge at this position might play the same role that Cl− does (8, 10). Consistent with this hypothesis, mutation of LeuT Glu-290 to a serine rendered binding of leucine dependent on Cl−, and corresponding mutations in Tyt1 resulted in a Cl−-dependent transporter (10). However, the E290S LeuT mutant was inactive for transport, and the Tyt1 mutant had only ∼1% of wild type activity (9), precluding further biochemical analysis.

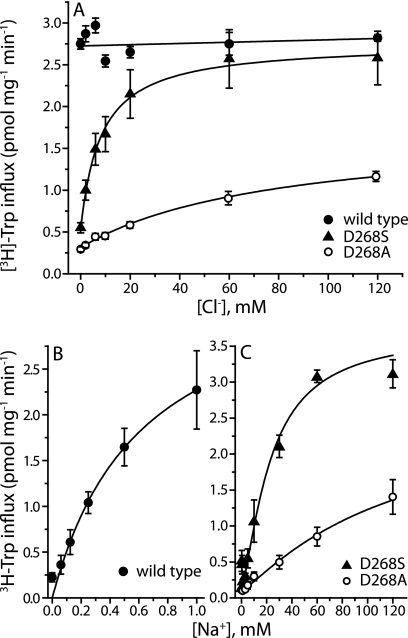

We studied the bacterial tryptophan transporter TnaT to test whether mutating the equivalent position, Asp-268, to serine would create a Cl−-dependent transporter with sufficient activity for definitive biochemical analysis. Remarkably, transport by D268S TnaT was stimulated by Cl− with a Km similar to that of SERT and a vmax similar to that of wild type TnaT (Fig. 3A and Table 2). When Asp-268 was replaced with alanine, the resultant transporter also required Cl−, but the Km was more than 10-fold higher than that of D268S (Fig. 3A and Table 2), consistent with the idea that the serine hydroxyl contributes to Cl− coordination. D268S protein was expressed at levels similar to that of wild type TnaT, although D268A expression levels were lower (supplemental Fig. S2). We also found that the Na+ dependence of Trp transport was altered in TnaT D268S and D268A mutants. Specifically, the Km for Na+ increased 35-fold from wild type to D268S and a further 13-fold in D286A (Fig. 3, B and C, see legend to Fig. 3 for Km values), suggesting that in TnaT the carboxyl group of Asp-268 may stabilize Na+ binding more effectively than the presence of Cl− in the D268S or D268A mutants. Similarly, the Cl−-dependent mutant of Tyt1 also required higher Na+ concentrations for activation of transport (9). The availability of fully functional Cl−-dependent and -independent forms of TnaT allowed us to study the effect of mutation at candidate Cl−-binding site residues in both settings. Thus, we would be able to link observed changes to the formation of a functional Cl− site in a way that was not possible with SERT, GAT-1, or previously studied prokaryotic transporters.

FIGURE 3.

Substitution of Asp-268 with a serine renders TnaT chloride-dependent. A, initial transport rates of [3H]tryptophan were obtained for wild type TnaT (filled circles) and mutants D268S (triangles) and D268A (open circles) over a range of Cl− concentrations (0–120 mm, with gluconate replacing Cl−). Mutation of Asp-268 to serine introduced a Cl− requirement for transport, and mutation to alanine led to a profound increase in the Km for Cl− (Table 2). B and C, mutation of Asp-268 also affected the Km for Na+ which increased from 0.6 ± 0.11 mm in wild type (B in the absence of Cl−) to 22.1 ± 2.4 mm in D268S and 286 ± 51 mm in D268A (C in the presence of saturating Cl−). Na+ was substituted with NMDG (B and C) and Cl− with SO42− (B) or gluconate (C). SO42− and gluconate were equally good as inert Cl− replacements. Each value represents the mean and S.E. of three independent experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

TABLE 2.

Initial rates of transport measured in E. coli

The initial rates of transport (1 min) were measured in E. coli CY15212 expressing the wild type or indicated mutants as described under “Experimental Procedures” and expressed in terms of total cell protein. The percentage of activity at zero Cl− was calculated relative to that at maximal Cl− (100 mm). Each value represents the mean and S.E. of two to four independent experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

| TnaT | [3H]Trp influx |

Km Cl− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mm [Cl−] | 100 mm [Cl−] | ||

| pmol/mg/min | |||

| Wild type | 3.15 ± 0.03 | 3.26 ± 0.09 | |

| D268S | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 2.87 ± 0.19 | 3.07 ± 0.21 |

| D268A | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 1.65 ± 0.11 | 37.34 ± 6.5 |

| D268T | 0.67 ± 0.09 | 2.76 ± 0.10 | 5.78 ± 0.87 |

| Y47F | 2.93 ± 0.26 | ||

| Y47D | 0.43 ± 0.01 | ||

| Y47A | 0.55 ± 0.03 | ||

| Y47F/D268S | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 1.83 ± 0.21 | 30.13 ± 7.92 |

| Y47D/D268S | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | |

| Y47A/D268S | 0.12 ± 0.006 | 0.11 ± 0.003 | |

| N264A | 2.05 ± 0.15 | ||

| N264A/D268S | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | |

| N264D | 2.81 ± 0.19 | ||

| N264D/D268S | 2.52 ± 0.10 | 1.82 ± 0.23 | |

| S232A | 0.11 ± 0.01 | ||

| S232A/D268S | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | |

| S232D | 0.67 ± 0.1 | ||

| S232D/D268S | 3.41 ± 0.15 | 3.22 ± 0.16 | |

| S265A | 3.91 ± 0.73 | ||

| S265A/D268S | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 2.67 ± 0.22 | 11.68 ± 0.84 |

| S265E/D268S | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.006 | |

| Q228A | 0.25 ± 0.007 | ||

| Q228A/D268S | 0.15 ± 0.007 | ||

| Q228C | 0.17 ± 0.007 | ||

| Q228D | 0.06 ± 0.007 | ||

| Q228E | 0.07 ± 0.007 | ||

| Q228L | 0.05 ± 0.007 | ||

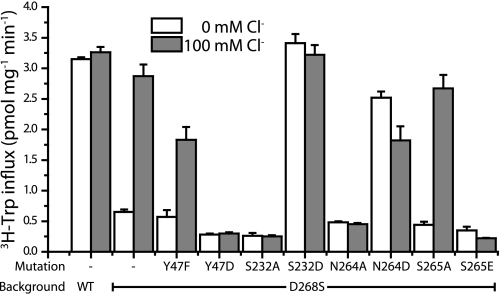

Based on the above findings, we generated a structural model for a putative Cl− binding-site in TnaT D268S (Fig. 1B). In the background of D268S, we introduced mutations at each position proposed to participate in Cl− binding to SERT. As in SERT, introduction of a carboxylic side chain at putative coordinating residues rendered TnaT Cl−-independent (S232D/D268S and N264D/D268S; Fig. 4 and Table 2). The latter mutant was actually slightly more active in the absence of Cl−.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of the artificial chloride site in TnaT. CY15212 cells expressing TnaT mutants were assayed for tryptophan uptake. Residues Tyr-47, Asn-264, Ser-232, and Ser-265 were mutated to aliphatic or negatively charged amino acids. The initial transport rates were obtained in the presence (gray) and absence (white) of Cl−, which was substituted by 100 mm gluconate. Transport activity is presented as pmol mg protein−1 min−1. Each value represents the mean and S.E. of three independent experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

Replacement by alanine at each position (in the D268S background) resulted in proteins with low transport activity (Fig. 4 and Table 2). In the case of N264A/D268S, this was not accompanied by changes in protein expression (supplemental Fig. S2), and moreover, in the wild type Cl−-independent background, the N264A mutant retained most of its transport activity (Table 2). In LeuT, the corresponding residue (Asn-286) coordinates Na1 (11), and in TnaT, the N264A mutation raised the Km for Na+ over 100-fold (from 0.6 ± 0.2 to 82 ± 34 mm), consistent with Asn-264 in TnaT having a similar role in addition to Cl− coordination (Fig. 1B). Additive decreases in Na+ affinity from N264A and D268S mutations are therefore likely to contribute to the low activity of N264A/D268S, but the complete lack of Cl− stimulation in this mutant indicates a direct role for Asn-264 in Cl− coordination (Table 2).

The other residue predicted to coordinate both Na+ and Cl− in our model is Ser-232 (Fig. 1B). S232A/D268S had low transport activity (but normal expression; see Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S2), but the S232A single mutant also had low activity (Table 2), consistent with the idea that this position in TnaT coordinates Na1, like the corresponding Thr-254 in LeuT.

Aliphatic substitutions were not tolerated at Tyr-47, although the Y47A mutation in wild type TnaT also led to low activity (Table 2) and low expression (supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that the effect was not entirely due to an influence on Cl− binding. Like the corresponding mutant in SERT (Fig. 2), Y47F/D268S was functional and had a significantly higher Km for Cl− than D268S (Table 2), supporting the idea that the phenolic hydroxyl participates in Cl− coordination.

We also tested whether Ser-265 (equivalent to Cys-369 in SERT) also plays a role in the TnaT Cl− site. S265E/D268S was slightly inhibited by Cl−, but its activity was too low to accurately determine the extent of inhibition (Fig. 4 and Table 2). However, substitution by alanine at this position (S265A/D268S) led to a 4-fold increase in the Km for Cl− compared with that of D268S (Table 2), suggesting that this position might play a role in Cl− coordination in TnaT. Importantly, the S265A mutation did not inhibit transport in wild type TnaT (Table 2).

Replacement of the conserved Gln-228 in TnaT-D268S with alanine or in wild type TnaT with aspartate, glutamate, leucine, alanine, or cysteine led to mutants with activity too low to allow further analysis (Table 2). However, we note that the Q228A mutation was slightly more active in the wild type background than in D268S (Table 2). The fact that mutation of this residue led to dramatically decreased activity, even in wild type TnaT, indicates that it is critical for normal function independent of the Cl− requirement. The side chain amide of the equivalent residue in LeuT (Gln-250) donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone oxygen of Gly-26, providing an interaction between TM helices 1b and 6a that is conserved in our models of SERT and TnaT, despite the other local differences between the proteins (Fig. 1). Destabilization of this interaction by mutation may therefore have a significant, but indirect, effect on the formation of both the Na1- and Cl−-binding sites.

Interaction between Sodium and Chloride

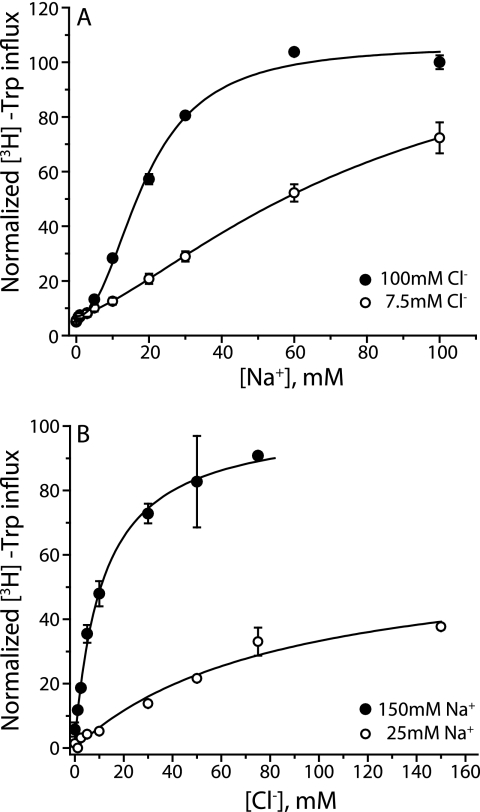

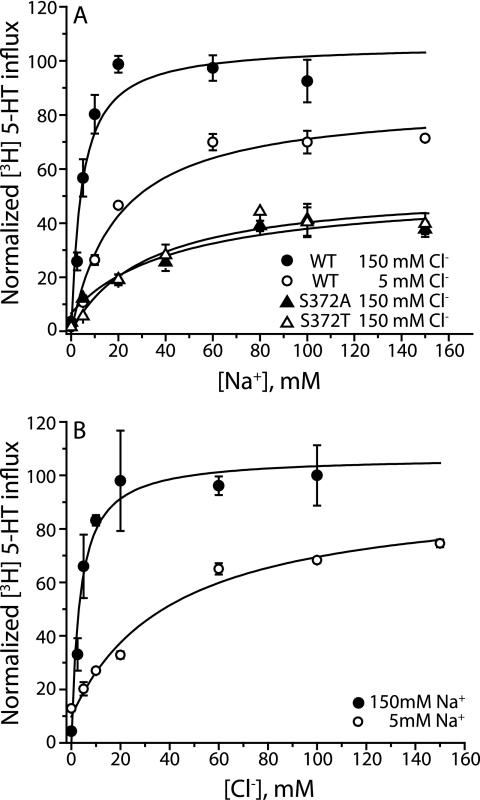

Calculation of the electrostatic interaction energy between Glu-290 and Na1 in LeuT suggested that the negatively charged carboxylate favored Na1 binding (8), and the effect of Cl− on transient Na+ currents in GAT-1 suggested that it increased Na+ affinity (32). To test whether a bound Cl− ion could similarly enhance Na+ binding in SERT and in the Cl−-dependent D268S TnaT mutant, we measured the Km for Na+ at saturating and subsaturating Cl− concentrations. In TnaT-D268S, Cl− enhanced the potency for Na+ 4-fold when transport measured in saturating Cl− was compared with that in low Cl− (Fig. 5A). Likewise, in SERT, the Km for Na+ was more than 3-fold higher at low Cl− than at saturating Cl− (Fig. 6A). To extend these observations, we tested alanine and threonine mutants at Ser-372 (a Cl−-binding site residue) previously found to have 10-fold higher Km for Cl−, suggesting weak Cl− coordination (8). We found that S372A and S372T mutants also had increased Km for Na+ compared with wild type SERT, even at saturating Cl− (Fig. 6A). This is unlikely to be a direct effect of the mutation on Na+ coordination because the corresponding residue in LeuT (Glu-290) was not found to interact with either bound Na+ ion in x-ray crystal structures (11). These results are consistent with Cl− enhancing the binding affinity for Na+ in both SERT and the Cl−-dependent TnaT-D268S. The Na+ dependence of TnaT was frequently found to be sigmoidal (as in Fig. 5A), suggesting the participation of more than one Na+ ion. The two Na+ sites found in LeuT are preserved in TnaT, providing a structural basis for the sigmoidicity. However, the Na2 ion in our model of TnaT is >7.5 Å from any residue proposed here to coordinate Cl−, and therefore Na2 is less likely to be directly influenced by Cl− binding.

FIGURE 5.

Mutual interactions between chloride and sodium in TnaT D268S. A, effect of Cl− on Na+ potency was measured in CY15212 cells expressing D268S TnaT. Tryptophan uptake was tested over a range of Na+ concentrations in saturating (100 mm, filled circles; Km = 22.1 ± 2.4 mm) or subsaturating Cl− (7.5 mm, open circles; Km = 81 ± 7 mm). B, the effect of Na+ on Cl− potency was measured over a range of Cl− concentrations at saturating (150 mm, filled circles; Km Cl− = 3 ± 0.2 mm) or subsaturating (25 mm, open circles; Km Cl− = 80 ± 14 mm) Na+. Sodium was substituted by NMDG (A and B) and Cl− with gluconate (A) or diatrizoate (B). Transport activity was normalized so that 100 is maximal activity in saturating Cl− (A) or maximal activity in saturating Na+ (B). Km values represent the means and S.E. of three independent experiments. The error bars in the figure represent S.D. in a representative experiment.

FIGURE 6.

Mutual interactions of chloride and sodium in SERT. A, HeLa cells expressing wild type SERT were assayed for 5-HT uptake for 10 min at the indicated Na+ concentrations in saturating (150 mm, filled circles; KmNa+ = 4.4 ± 0.1 mm) or subsaturating Cl− (5 mm, open circles; KmNa+ = 14.5 ± 0.4 mm). Activation by Na+ was also measured for mutants S372A (filled triangles; KmNa+ = 37 ± 5 mm) and S372T (open triangles; KmNa+ = 46 ± 9 mm), known to have increased Km for Cl−. B, potency for Cl− was measured at saturating (150 mm Na+, filled circles; KmCl− = 3.6 ± 0.9 mm) or subsaturating (5 mm Na+, open circles; 44 ± 2 mm) Na+ concentrations. Sodium was substituted with NMDG and Cl− with SO42−. Transport activity was normalized as in Fig. 5. The Km values represent the means and S.E. of three (A) and four (B) independent experiments. The error bars in the figure represent S.D. in a representative experiment.

We would also expect a reciprocal increase in Cl− affinity upon Na+ binding, as an additional consequence of the proximity between Na+- and Cl−-binding sites. To test the hypothesis that Na+ stabilizes Cl− binding, we measured the Km for Cl− in both the Cl−-dependent TnaT-D268S mutant and wild type SERT, at saturating Na+ and at a concentration close to the Km for Na+. In TnaT-D268S, the Km for Cl− increased 25-fold at low Na+ relative to saturating Na+ (Fig. 5B). Consistent with these results, in wild type SERT the Km for Cl− was 12-fold higher at 5 mm than at saturating Na+ (Fig. 6B), suggesting that Na+ indeed enhances the Cl− binding affinity.

DISCUSSION

Ion binding and release are critical steps in the mechanism of ion-coupled substrate transport. In SERT, Na+ and Cl− are required for 5-HT-dependent conformational changes that lead to translocation (33–35). Previous studies provided preliminary information about the location of the Cl−-binding site (8, 10). The strategy involved substituting glutamate or aspartate near the predicted Cl− sites in SERT or GAT-1 and replacing carboxylic residues in LeuT and Tyt1 with potential Cl− coordinating amino acids such as serine. Although these studies established that the Cl− requirement could be bypassed by inserting a carboxylic side chain at a given position, the data did not identify the replaced residue as a direct Cl− ligand because the mere proximity of a carboxylate at any position near Na1 might stabilize its binding and remove the Cl− requirement.

An additional problem with previous studies was the relatively poor functional activity of the mutants. For the Cl−-insensitive SERT and GAT-1 mutants and the Cl−-dependent LeuT and Tyt1 mutants, the loss in activity relative to wild type made them unattractive as models from which to draw firm conclusions about the role of individual residues. We now show that a single mutation, D268S, in the homologous bacterial tryptophan transporter TnaT produces a fully active Cl−-dependent protein that allowed us to examine potential Cl− coordinating residues in both Cl−-dependent and Cl−-independent settings and to relate the effect of mutations directly to the participation of Cl− in transport. The results give us a much more precise characterization of the Cl− site and its interaction with Na+ in this family of transporters.

In the work described here, we show that a set of four residues in both SERT and TnaT-D268S are responsible for directly coordinating Cl−. These residues are Tyr-121, Ser-336, Asn-368, and Ser-372 in SERT and Tyr-47, Ser-232, Asn-264, and the serine-replacing Asp-268 in TnaT (Fig. 1). Two of the residues, Ser-336(232) and Asn-368(264) (SERT(TnaT) numbering), correspond to LeuT residues that form the site for Na1 (11), and the other two are distal to the Na1 site. For the two positions likely to participate in coordination of both Na+ and Cl−, mutation to glutamate or aspartate led to Cl−-independent transport both in SERT (Fig. 2 and Ref. 8) and in TnaT-D268S (Fig. 4), presumably because the ionized side chain carboxylate can partially satisfy the need for a negative charge near Na1. Mutation to alanine at either position severely diminished activity in the Cl−-dependent forms of SERT and TnaT (Tables 1 and 2). At least part of this inhibitory effect was apparently due to impaired Na1 binding because in the context of Cl−-independent wild type TnaT, the S232A mutation also ablated transport activity, and the N264A mutation led to partial activity loss and a higher Km for Na+ (results). However, the N264A mutation dramatically decreased transport in the Cl−-dependent TnaT-D268S compared with the modest decrease in wild type TnaT. Although this decrease in the double mutant might result from additive decreases in Na+ affinity, the remaining activity of this mutant was completely independent of Cl− despite retaining all of the other proposed Cl− coordinating residues. These results strongly support a role for Asn-264 in coordinating Cl−, a point on which previous binding models differed (8, 10).

The two residues that coordinate Cl− but not Na+ are Ser-372(268) and Tyr-121(47). Replacement of Ser-372(268) with aspartate produced Cl−-independent proteins in both cases (in TnaT, this is the wild type protein) likely by placing a negative charge near Na1 as described above (8). Replacement with alanine dramatically increased the Km for Cl− in both transporters (Fig. 3A and Ref. 8), as expected if Cl− was still required, but affinity was reduced by loss of the coordinating hydroxyl group. Mutations to aspartate or glutamate at Tyr-121(47) were not well tolerated, leading to low expression, but loss of the phenolic hydroxyl group in the phenylalanine mutants increased the Km for Cl− (Tables 1 and 2), consistent with reduced Cl− affinity.

Two additional nearby positions were examined, despite being more distant from the bound Cl− ion in SERT and TnaT homology models. Both transporters were extremely sensitive to mutation of Gln-332(228), an effect unlikely to result from a change in Cl− affinity because the mutations had similar effects in wild type TnaT (Table 2). In SERT, Q332C had measurable activity and was still stimulated by Cl−, although the Cl− Km was elevated (Table 1). In GAT-1, Kanner and co-workers (36) observed that mutation of the corresponding Gln-291 inhibited transport significantly less in a Cl−-independent mutant than in wild type, suggesting participation of this residue in Cl− coordination. Because the side chain nitrogen atom of this glutamine residue is >7 Å from that of Asn-368(264) in our models, it seems unlikely that both residues simultaneously coordinate Cl− (Fig. 1). It is possible that both participate, but they do so at different points in the reaction cycle, or that the homology models exaggerate the actual distance between the two.

Replacement of Cys-369 in SERT by glutamate did not ablate Cl− stimulation, but the corresponding S265E mutation in TnaT-D268S decreased stimulation by Cl−, suggesting that this residue affects the Cl−-binding site created in TnaT more than the binding site in SERT. The corresponding S328E mutation in GAT-1 was also less responsive to Cl− than wild type transporter (10). C369S and C369A in SERT and S265A in TnaT-D268S were highly functional and Cl−-dependent. However, Km values for Cl− were elevated in the alanine mutants, with a 2-fold increase in SERT C369A and a 4-fold increase in TnaT-S265A/D268S. Thus, the effect of replacing TnaT-Ser-265 with either glutamate or alanine was greater than with the corresponding mutations of Cys-369 in SERT, suggesting that coupling between this position and the Cl− site varies among NSS transporters. Part of this difference may be due to distance. Specifically, in the SERT homology model, Cys-369 is farther from the Cl− than Ser-265 in the homology model of TnaT-D265S, although this ∼1-Å difference is relatively small given the likely uncertainty in the structural models (8, 37).

Although mutants of both Tyr-121 and Cys-369 increased the Km for Cl− in SERT, replacement with aliphatic residues was much more deleterious for Tyr-121 (or Tyr-47 in TnaT) than for Cys-369 (or Ser-265), indicating that the tyrosine is more critical (Tables 1 and 2). Even the relatively conservative mutation of TnaT Tyr-47 to Phe led to a 10-fold increase in the Km for Cl−. The ability of Phe to replace Tyr as a Cl− ligand was also observed in crystal structures of E. coli ClC (38). By comparison, the less conservative mutation of Ser-265 to alanine increased Km only 4-fold (Table 2). Similar results were obtained with the corresponding SERT mutants (Table 1).

We recently showed that mutations at the same positions shown here to coordinate Cl− also affected the Cl− dependence of antidepressant binding to SERT (39). Aliphatic substitutions generally reduced affinity for imipramine and fluoxetine (Prozac) and prevented Cl− from stimulating their binding. Substitutions with aspartate also prevented Cl− from enhancing antidepressant affinity but did not decrease affinity markedly. In contrast, cocaine affinity was not influenced by Cl−, and these mutations generally did not affect cocaine binding. These results highlight the variety of Cl−-dependent behaviors that rely on the Cl− site in SERT.

Both Na1- and Na2-binding sites present in LeuT are well conserved in SERT (12), but the Na+:5-HT stoichiometry is 1:1 (40, 41). Therefore, only one of the two Na+ ions bound to SERT is transported, and the other is likely to remain bound throughout the transport cycle. The results presented here strongly support the proposed location of bound Cl− immediately adjacent to the Na1 site, separated only by side chain atoms of Ser-336(232) and Asn-368(264) (8, 10). Because the Na+ dependence of transport is sensitive to Cl−, we consider it likely that this Na+ dependence represents binding and dissociation of Na1. Nevertheless, x-ray structures of the structurally related transporters vSGLT and Mhp1, which resemble our own model of the cytoplasm-facing conformation of LeuT, show that coordination of Na2 is poor in that conformation due to separation of TMs 1 and 8 (16, 42–44). Thus, although binding of Na1 appears to determine the Na+ dependence of transport, Na2 is more likely to be released to the cytoplasm with substrate, indicating that the two Na+ ions play distinct roles in the transport cycle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joan Gesmonde for excellent technical support. We greatly appreciate Baruch Kanner for sharing his unpublished study on the Cl−-binding site of GAT-1.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM075347 and DA007259 (to G. R.). This work was also supported by an Autism Speaks postdoctoral fellowship (to S. T.) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Collaborative Research Center 807 “Transport and Communication across Biological Membranes” (to L. R. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- NSS

- neurotransmitter:sodium symporter

- 5-HT

- 5-hydroxytryptamine

- SERT

- serotonin transporter

- GAT-1

- γ-aminobutyric acid transporter

- β-CIT

- (−)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) tropane

- NMDG

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- TM

- transmembrane helix.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rudnick G. (1998) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 30, 173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gether U., Andersen P. H., Larsson O. M., Schousboe A. (2006) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murphy D. L., Lerner A., Rudnick G., Lesch K. P. (2004) Mol. Interv. 4, 109–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iversen L. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, (Suppl. 1) S82–S88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howell L. L., Kimmel H. L. (2008) Biochem. Pharmacol. 75, 196–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rudnick G. (2002) in Neurotransmitter Transporters, Structure, Function, and Regulation (Reith M. E. A., ed) pp. 25–52, 2nd Ed., Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caplan D. A., Subbotina J. O., Noskov S. Y. (2008) Biophys. J. 95, 4613–4621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forrest L. R., Tavoulari S., Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G., Honig B. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12761–12766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao Y., Quick M., Shi L., Mehler E. L., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2010) Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zomot E., Bendahan A., Quick M., Zhao Y., Javitch J. A., Kanner B. I. (2007) Nature 449, 726–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamashita A., Singh S. K., Kawate T., Jin Y., Gouaux E. (2005) Nature 437, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beuming T., Shi L., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1630–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh S. K., Yamashita A., Gouaux E. (2007) Nature 448, 952–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou Z., Zhen J., Karpowich N. K., Goetz R. M., Law C. J., Reith M. E., Wang D. N. (2007) Science 317, 1390–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh S. K., Piscitelli C. L., Yamashita A., Gouaux E. (2008) Science 322, 1655–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forrest L. R., Zhang Y. W., Jacobs M. T., Gesmonde J., Xie L., Honig B. H., Rudnick G. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10338–10343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Celik L., Schiøtt B., Tajkhorshid E. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 1600–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi L., Quick M., Zhao Y., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 667–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forrest L. R., Rudnick G. (2009) Physiology 24, 377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao Y., Terry D., Shi L., Weinstein H., Blanchard S. C., Javitch J. A. (2010) Nature 465, 188–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Goldberg N. R., Ueda K., Beppu T., Beckman M. L., Das S., Javitch J. A., Rudnick G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12703–12709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quick M., Yano H., Goldberg N. R., Duan L., Beuming T., Shi L., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26444–26454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quick M., Javitch J. A. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3603–3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamdar G., Penado K. M., Rudnick G., Stephan M. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4038–4045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen N., Reith M. E. (2003) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479, 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Y., Zomot E., Kanner B. I. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22092–22099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30807–30813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen J. G., Liu-Chen S., Rudnick G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12675–12681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Šali A., Blundell T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brooks B. R., Bruccoleri R. E., Olafson B. D., States D. J., Swaminathan S., Karplus M. (1983) J. Comp. Chem. 4, 187–217 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mari S. A., Soragna A., Castagna M., Santacroce M., Perego C., Bossi E., Peres A., Sacchi V. F. (2006) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 100–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mager S., Kleinberger-Doron N., Keshet G. I., Davidson N., Kanner B. I., Lester H. A. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 5405–5414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitchell S. M., Lee E., Garcia M. L., Stephan M. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24089–24099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sato Y., Zhang Y. W., Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Rudnick G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22926–22933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36213–36220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ben-Yona A., Bendahan A., Kanner B. (November 23, 2010) J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M110149732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Forrest L. R., Tang C. L., Honig B. (2006) Biophys. J. 91, 508–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Accardi A., Lobet S., Williams C., Miller C., Dutzler R. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362, 691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tavoulari S., Forrest L. R., Rudnick G. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 9635–9643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Talvenheimo J., Fishkes H., Nelson P. J., Rudnick G. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 6115–6119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Quick M. W. (2003) Neuron 40, 537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Faham S., Watanabe A., Besserer G. M., Cascio D., Specht A., Hirayama B. A., Wright E. M., Abramson J. (2008) Science 321, 810–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shimamura T., Weyand S., Beckstein O., Rutherford N. G., Hadden J. M., Sharples D., Sansom M. S., Iwata S., Henderson P. J., Cameron A. D. (2010) Science 328, 470–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li J., Tajkhorshid E. (2009) Biophys. J. 97, L29–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.