Abstract

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) is a transcriptional factor involved in detoxification responses to pollutants and in intrinsic biological processes of multicellular organisms. We recently described that Vav3, an activator of Rho/Rac GTPases, is an Ahr transcriptional target in embryonic fibroblasts. These results prompted us to compare the Ahr−/− and Vav3−/− mouse phenotypes to investigate the implications of this functional interaction in vivo. Here, we show that Ahr is important for Vav3 expression in kidney, lung, heart, liver, and brainstem regions. This process is not affected by the administration of potent Ahr ligands such as benzo[a]pyrene. We also report that Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice display hypertension, tachypnea, and sympathoexcitation. The Ahr gene deficiency also induces the GABAergic transmission defects present in the Vav3−/− ventrolateral medulla, a main cardiorespiratory brainstem center. However, Ahr−/− mice, unlike Vav3-deficient animals, display additional defects in fertility, perinatal growth, liver size and function, closure, spleen size, and peripheral lymphocytes. These results demonstrate that Vav3 is a bona fide Ahr target that is in charge of a limited subset of the developmental and physiological functions controlled by this transcriptional factor. Our data also reveal the presence of sympathoexcitation and new cardiorespiratory defects in Ahr−/− mice.

Keywords: Axon, Cytoskeleton, Dioxin, Mouse Genetics, Neuron, Respiration, Rho, Xenobiotics, GDP/GTP Exchange Factors, Hypertension

Introduction

Ahr3 is a transcriptional factor that belongs to the class VII basic region helix-loop-helix/Per/Arnt-Sim protein family (1–3). This molecule has attracted a lot of attention in the toxicology field because it acts as the main intracellular target for polycyclic and halogenated aromatic environmental pollutants such as benzo[a]pyrene and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (1, 3, 4). Activation of Ahr by those drugs induces the transcription of genes containing XRE sites in their promoter regions (1, 4). Known Ahr targets include loci encoding cytochrome P450 family members in charge of the phase I detoxification response (5–9), phase II detoxification proteins (10–12), metabolism-related enzymes (13–15), and many other molecules (16, 17).

Recent results also suggest that Ahr can participate in xenobiotic independent functions. Accordingly, it has been discovered that Ahr can also become activated by natural ligands present in the diet or generated endogenously by mammalian cells (1). Ligand-independent functions have been also postulated for Ahr family proteins (18–22). The analysis of Ahr-deficient mice has confirmed the implication of Ahr in developmental and physiological events, including female fertility (23, 24), perinatal growth (25, 26), blood normotensia (27), and production of normal peripheral lymphocyte numbers (25). Ahr also plays critical roles in liver development and function, because its gene deficiency causes reductions in liver size (25, 28), hepatic portal fibrosis (25, 28), defective neonatal closure of the ductus venosus (29), disruptions in lipid metabolism (25, 28), and prolonged intrahepatic hematopoiesis (28). Although the biological cause of most of those defects remains unknown, recent reports have linked some of them to specific Ahr transcriptional targets. For example, the liver fibrosis seems to be mediated by the derepression of latent TGF-β-binding protein 1 in Ahr−/− mice (30–32). The increased wound healing observed in the skin of Ahr−/− mice has also been linked to increased TGF-β signaling in keratinocytes (33). Finally, the high retinoic acid content of livers from neonate Ahr−/− mice has been associated with reduced expression of the Cyp2C39 gene, a cytochrome P450 family member that displays retinoic acid 4-hydrolase activity (34). It is therefore likely that the transcriptional deregulation of other Ahr gene targets could contribute to additional dysfunctions present in Ahr-deficient mice.

We have recently reported that Ahr regulates the constitutive expression levels of the Vav3 proto-oncogene in MEFs and immortalized fibroblasts (35). This gene encodes a tyrosine phosphorylation GDP/GTP exchange factor for Rho/Rac family GTPases that plays important roles in cytoskeleton-linked signaling events activated by transmembrane and/or cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases (36, 37). Recent genetic experiments using knock-out mice have revealed that this GDP/GTP exchange factor is important for cardiovascular homeostasis (38), adequate control of sympathetic activity (38), the timely development of the cerebellum in early postnatal stages (39), and axon guidance events in inhibitory GABAergic cells of the VLM (40), a brainstem region involved in the coordinated control of cardiovascular, respiratory, adrenal, and renal activities (41, 42). Cooperating with other Vav family members (Vav1 and Vav2), Vav3 also participates in the development, selection, and antigen responses of lymphocytes (43), the effector functions of other hematopoietic lineages, angiogenesis (43), and axon guidance events (44). The regulation of Vav3 by Ahr relies on the recognition of one of the three XRE sites present in the Vav3 gene promoter and, unexpectedly, takes place in a ligand-independent manner (35). Vav3 appears to be a bona fide Ahr target, because Ahr−/− and Vav3−/− MEFs show similar cytoskeletal defects (35). Moreover, the defective cytoskeletal properties of Ahr-deficient MEFs can be rescued by overexpressing Vav3 (35).

These above observations prompted new questions, including the issues of whether Ahr controls Vav3 expression in other cell types and tissues, the actual physiological relevance of this new functional relationship, and whether the lack of Vav3 expression can recapitulate some of the phenotypic defects found in Ahr-deficient mice. To approach those issues, we decided to focus our attention on the side-by-side comparison of Ahr- (25) and Vav3-deficient (38) mice. Here, we provide evidence indicating that Ahr controls the expression of Vav3, but not other Vav family members, in a tissue-dependent manner in vivo. We also report previously unknown functions for Ahr in the control of brainstem-dependent functions, including cardiovascular and breathing activity, that mimic those observed in Vav3-deficient mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Use

Ahr and Vav3 knock-out mice have been reported previously (25, 38, 45). Vav1−/−;Vav2−/−;Vav3−/− mice were generated by crosses with Vav1−/− (46), Vav2−/− (45, 47, 48), and Vav3−/− mice and subsequent homogenization in the BL10 genetic background. Unless otherwise stated, 4-month-old mice were used in experiments. When appropriate, and depending on the experiment performed, animals were anesthetized with either sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg body weight, Sigma) or urethane (2 mg/kg body weight, Sigma). All animal work was carried out following regulations set forth by the respective Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Salamanca University, and Extremadura University Animal Care and Use Committees.

RT-PCR Determinations

Vav3, Vav2, and Ahr mRNA levels were determined by quantitative reverse transcription PCR in indicated tissues. To this end, total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), retrotranscribed (QuantiTech SYBR Green RT-PCR kit, Qiagen), and amplified in an iCycler iQ apparatus (Bio-Rad) using SYBR Green as the fluorescent probe. PCR controls included amplifications of RpLp0 mRNA. Sequences of primers used are available upon request.

Xenobiotic Treatments

Wild type mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/kg of body weight of benzo[a]pyrene (Sigma) and euthanized 24 h later for tissue extraction.

Determination of Breathing Activities

In the case of direct determinations, mice were slightly anesthetized with urethane (1 mg/kg body weight). In stereotaxic experiments, mice were deeply anesthetized with urethane (see under “Animal Use”). In both cases, mice were connected in their diaphragm region with a flexible wire to a force transducer. Breathing parameters under study were collected using a digital data recorder (MacLab/4e, AD Instruments) and integrated using the Chart version 3.4 software (AD Instruments).

Hemodynamic Studies

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and arterial pressures recorded by catheterization of the right carotid artery with a pressure probe connected to a digital data recorder (MacLab/4e, AD Instruments), as described previously (49). Recordings were subsequently analyzed with the Chart version 3.4 software (AD Instruments). Blood pressure and heart rates were recorded after a 20-min-long stabilization period of animals after catheterization. Blood pressure and heart frequency were also recorded in conscious mice using the tail-cuff method with an automated multichannel system and a photoelectric sensor (Niprem 546, Cibertec SA).

Analysis of Related Cardiovascular and Sympathetic Molecules

Angiotensin converting enzyme activities in heart extracts were determined using a luminescence method (50). ELISA kits were used to measure plasma levels of AngII (angiotensin II ELISA kit, SPI Bio), adrenaline (CatCombi ELISA, IBL), and noradrenaline (CatCombi ELISA, IBL). In the case of catecholamine determinations, animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital before euthanasia.

Histology and Pathological Assessment of Mice

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and paraffin-embedded. 2–3-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma). For immunohistochemical experiments, tissue sections were incubated with commercial antibodies obtained from either Millipore/Chemicon (tyrosine hydroxylase, v-GAT, GAD65, and GAD67) or Sigma (GABAA receptor, GABA). In the case of Vav3, a homemade rabbit polyclonal antibody was used (36, 39). After overnight incubations, tissue slides were rinsed with PBS, incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a milk/phosphate-buffered saline solution containing a goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare), rinsed with PBS, and developed with diaminobenzidine (Dako). Alternatively, we used Cy5- and Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) to visualize the recognized proteins by immunofluorescence microscopy. Quantifications of immunohistochemical experiments were done blindly using the Metamorph-Metaview software (Molecular Devices). Quantification of fluorescence signals was done using the LSM Image Browser software (version 3.2.0.115, Zeiss).

Tissue Fibrosis Analysis

For quantification of the total collagen present in tissues, the hydroxyproline content was determined using a spectrophotometric method (51). Total collagen was calculated assuming that collagen contains a 12.7% of hydroxyproline.

In Situ Hybridization Studies

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized, treated with proteinase K (Dako), washed with PBS, and soaked in 2× SSC. Digoxigenin-11-UTP-labeled Ahr and Vav3 sense and antisense cRNA probes were synthesized using the digoxigenin RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). Template plasmids for the reverse transcription were pVS27 (for Ahr, nucleotides 915–1413) (52) and pVS2 (for Vav3, nucleotides 2181–2661) (36). After the probe hybridization for 6 h at room temperature, signals were detected using the digoxigenin nucleic acid detection kit (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Cytoarchitectural Criteria and Terminology

The terminology used for mouse brainstem regions was taken from a well known brain atlas (53). The RVLM was considered as the VLM region limited medially by the gigantocellular reticular nucleus and the inferior olive; laterally by the spinal trigeminal nucleus and tract; ventrally by the ventral medullar surface; dorsally by the nucleus ambiguus and the reticular formation; caudally by the rostral pole of the lateral reticular nucleus; and rostrally by the caudal pole of the facial motor nucleus. The CVLM was considered as the brainstem area flanked by the lateral reticular nucleus rostral wings and located immediately caudal to the RVLM.

VLM Microinjection Experiments

Mice were anesthetized with urethane, cannulated in the carotid artery to monitor in real time arterial pressure variations, and gently placed in a stereotaxic device (Kopf). After exposing the skull, the position of the head was adjusted under the visual guidance of a microscope in the stereotaxic apparatus so that the height of the skull surface at the lambda and bregma was the same (53). The interaural and midlines were taken as landmarks for the stereotaxic coordinates as follows: RVLM (3.05 mm caudal and 0.20 mm ventral to the interaural line and 1.20 mm lateral to the midline) and CVLM (3.45 mm caudal and 0.1 mm ventral relative to the interaural line and 1.15 mm lateral to the midline). After drilling a window in the occipital bone, we microinjected bilaterally buffered vehicle (30 nl), bicuculline (50 pmol in 30 nl, Sigma), and/or l-glutamate (100 pmol in 30 nl, Sigma) using a 40-μm internal diameter glass micropipette attached to a Hamilton syringe. When muscimol (Sigma) was used, 10 pmol in 30 nl were microinjected unilaterally. Environmental conditions (light, temperature, and background noise) were kept constant during experiments. Optimal targeting of the RVLM region in the l-glutamate experiments was confirmed by injecting the same neurotransmitter in the CVLM, since this molecule is known to induce different effects in both blood pressure levels and breathing rates if injected in each of those areas. Furthermore, we also introduced the same drug in areas close to the initial injection site to confirm that the physiological response obtained in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems was restricted to the targeted VLM area (in the case of wild type animals) or, alternatively, to verify that the absence of physiological responses in Ahr−/− and Vav3−/− mice was not due microinjections made outside the desired VLM region. Finally, we also microinjected in the targeted regions 30 nl of a 1% solution of Fast Green FCF104022 (Merck) and, after sacrificing the mice, obtained tissue sections from the brainstem to verify the localization of the marker by direct microscope examination.

Statistical Analyses

Experimental data were analyzed using either the one-tailed Student's t test or the one-way analysis of variance test depending on the type of experiment performed. p values lower than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. In all figures, values are given as the mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Reduced Vav3 Gene Expression in Selected Tissues of Ahr-deficient Mice

We have shown previously that Ahr is required for the constitutive expression of Vav3 in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (35). To verify whether this is a general effect in other cell types, we evaluated by RT-PCR the expression levels of Vav3 transcripts in a number of tissues obtained from adult wild type and Ahr−/− mice. We observed that Vav3 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the kidney, lung, heart, and liver of Ahr-deficient mice relative to those found in control tissues (see supplemental Fig. S1A). Such effect was tissue-specific, since we found no statistically significant variations in Vav3 transcript levels in samples obtained from Ahr−/− cerebella (supplemental Fig. S1A). Ahr was only required for proper expression of this Vav family member, because no significant changes were observed in Vav2 mRNA levels between Ahr−/− and control samples (supplemental Fig. S1B). We found no changes in the expression of the Ahr mRNA in tissues obtained from wild type and Vav3-deficient mice (supplemental Fig. S1C), indicating that the Ahr/Vav3 functional interaction is established in a unidirectional manner. Confirming previous cell culture experiments using MEFs (35), we observed no elevation of Vav3 mRNA levels upon intraperitoneal administration of a strong Ahr activator (benzo[a]pyrene) to wild type mice (supplemental Fig. S1D). These results indicate that, unlike other Ahr transcriptional targets (1, 4), the regulation of the constitutive expression of the Vav3 proto-oncogene does not seem to entail activation of Ahr by xenobiotics.

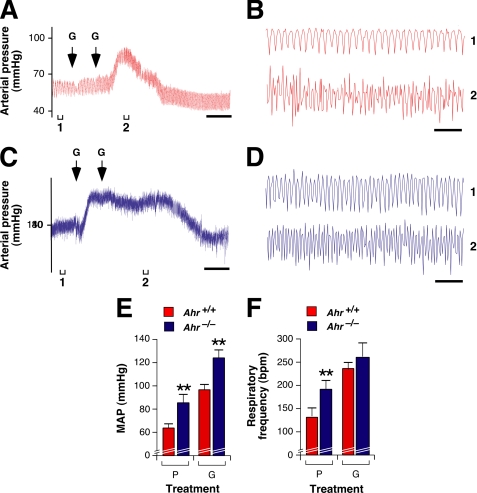

Ahr-deficient Mice Develop a Vav3−/−-like Respiratory and Cardiovascular Phenotype

Vav3-deficient mice display severe defects in breathing cycles and the cardiovascular system (38, 40). Given the reduced levels of Vav3 in Ahr−/− mice, we surmised that the phenotypes of Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice could show some overlap. In fact, previous results have shown that Ahr−/− mice develop hypertension by as yet unknown causes (27). In agreement with our hypothesis, we observed that Ahr−/− animals displayed tachypnea, showing inspiratory/expiratory cycles very similar to those observed in Vav3-deficient mice (Fig. 1, A and B). Likewise, as in the case of the latter mouse strain (38, 40), we detected high blood pressure (Fig. 1, C and E) and tachycardia (Fig. 1, D and F) in Ahr−/− animals both under sentient (Fig. 1, C and D) and unconscious (Fig. 1, E and F) conditions. This hypertensive condition was associated with up-regulation of the vasoconstrictor renin/AngII system, as demonstrated by the increased activity of the angiotensin-converting enzyme in the heart (Fig. 1G) and the elevated plasma levels of its biosynthetic end product, AngII (Fig. 1H). Similarly to Vav3-deficient mice (38), Ahr−/− animals also develop cardiovascular remodeling characterized by concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 2, A–E), thickening of the arterial media wall (Fig. 2, F and G), and increased numbers of vascular smooth muscle cells in arterial walls (Fig. 2H). We also found extensive fibrosis in the heart (Fig. 2I) and kidneys (Fig. 2J) obtained from Ahr-deficient mice. Instead, we found no evidence of pulmonary hypertension in Vav3−/− and Ahr−/− mice, as demonstrated by the lack of hypertrophy of the right heart ventricle (Fig. 2, A and C) and normal thickness of pulmonary arterioles (data not shown). Lack of pulmonary hypertension of Vav3−/− mice has been shown before (38, 40). These results indicate that Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice develop very similar dysfunctions in the respiratory and cardiovascular system.

FIGURE 1.

Ahr−/− mice display hyperventilation, hypertension, and tachycardia similar to those found in Vav3-deficient animals. A, example of representative real time recordings of the respiratory frequency of a wild type, an Ahr−/−, and a Vav3−/− mouse. Upward and downward deflections represent inspiration and exhalation movements, respectively. Scale bar, 1 s. B, quantitation of ventilation rates in mice of indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). bpm, breaths per min; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). NS, not statistically significant. C and D, systolic aortic pressure (SAP) (C) and heart rates (D) of conscious animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). bpm, beats per min. E and F, mean arterial pressure (MAP) (E) and cardiac activity (in beats/min) (F) of anesthetized animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). G, levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in hearts of the indicated mice (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). H, plasma levels of AngII in animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets).

FIGURE 2.

Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice develop similar cardiovascular remodeling. A, representative histological sections of hearts from a wild type and an Ahr-deficient mouse. Scale bar, 100 μm. B–E, evaluation of different heart parameters, including weight of left (LV) (B) and right ventricles (RV) (C), the LV/RV weight ratio (D), and the area of left ventricle myocytes (E) in animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5). *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). NS, not statistically significant. F, representative histological sections of aortas from a wild type and an Ahr−/− mouse. The aorta media wall is indicated by asterisks. Scale bar, 100 μm. G and H, evaluation of the thickness of the arteria media wall (G) and number of vascular smooth muscle cells present in the aorta of mice (H) of the indicated genotypes (n = 5). *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). I and J, fibrosis (evaluated as relative percentage of collagen content) in hearts (I) and kidneys (J) of mice of the indicated genotypes (n = 5). **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets).

SNS Hyperactivation in Ahr-deficient Mice

An important functional feature of Vav3-deficient mice is the development of sympathoexcitation even before the hypertension and cardiovascular dysfunctions develop in animals (38). The detection of tachycardia in Ahr−/− mice (Fig. 1, D and F) indicated that the Ahr gene deficiency may also have a hyperactivated SNS. To investigate this possibility, we first measured the plasma levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline, two catecholamines produced by the SNS (54). We detected 2-fold higher catecholamine plasma levels in Ahr−/− mice than in wild type animals (Fig. 3, A and B). These levels were, however, significantly lower than those found in the plasma of Vav3-deficient mice (Fig. 3, A and B). Given previous results with Vav3−/− mice, we next analyzed the structure of the adrenal gland medulla, a region composed of sympathetic cells that, upon upstream stimulation by SNS signals, releases adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream (55). Using histological analyses of serial sections, we observed that Ahr−/− mice had a marked hypertrophy of the adrenal medulla (Fig. 3C), leading to a significant increase in the total size of the gland (Fig. 3D). This hypertrophy was specific to this region, because we did not observe any significant change in the size of the cortical region of the gland (Fig. 3C). Because of this, the medulla/cortex ratio is significantly higher in adrenal glands of Ahr−/− mice than in those derived from wild type animals (Fig. 3E). Despite those marked histological changes, we did not detect any sign of pheochromocytoma in Ahr-deficient mice (data not shown). Similar histological alterations were observed in adrenal glands obtained from Vav3−/− mice (Fig. 3, D and E). To determine whether the medullary chromaffin cells were hyperactivated in Ahr−/− mice, we performed immunohistological experiments with antibodies to tyrosine hydroxylase, the protein that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the catecholamine biosynthesis (56). These experiments revealed higher expression levels of this enzyme in the adrenal medulla of Ahr−/− and Vav3−/− mice than in sections obtained from control animals (Fig. 3, F and G).

FIGURE 3.

Similar deregulation of the sympathetic nervous system in Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice. A and B, levels of adrenaline (A) and noradrenaline (B) in the plasma of 4-month-old mice of the indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). C, representative histological sections of adrenal glands from a wild type and an Ahr-deficient mouse. Scale bar, 150 μm. D and E, total adrenal gland weight (D) and medulla/cortex area ratio (E) in animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). au, arbitrary units. F, representative immunohistochemical staining with an anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (brown color) of adrenal gland sections obtained from a wild type and an Ahr−/− mouse. m, medulla; c, cortex. G, quantitation of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in adrenal gland sections obtained from animals of the indicated genotypes (n = 5). **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). NS, not statistically significant.

Phenotype of Ahr- and Vav3-deficient Mice Is Not Identical

Given the above results, we next explored whether other defects previously described in either Ahr−/− or Vav3−/− mice were shared between those two mouse strains. We could not detect in Vav3-deficient mice the previously described defects in the reproductive system (23, 24), early growth rates (25, 26), liver (25, 28, 29), spleen (28), and peripheral lymphocytes (25) of Ahr−/− mice (Table 1). This is not due to compensation events by either Vav2 or Vav3, because we did not find Ahr−/−-like defects in triple Vav1−/−;Vav2−/−;Vav3−/− mice (Table 1). Taken together, these results indicate that the Ahr and Vav3 gene deficiencies induce a similar, but not identical, phenotype in mice.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the noncardiovascular phenotypes of Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice

| Defects | Ahr−/− mice | Vav3−/− mice | Vav1−/−;Vav2−/−;Vav3−/− mice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced female fertility | Yes | No | No |

| Reduced postnatal growth rates | Yes | No (38)a | No |

| Smaller liver | Yes | No | No |

| Prolonged liver hematopoiesis | Yes | No | No |

| Improper closure of ductus venosus | Yes | No | No |

| Increased lipid content in neonate livers | Yes | No | No |

| Splenomegalia | Yes | No | No |

| Defects in peripheral lymphocytes | Yes | No (38) | Yes (69)b |

| Skin wound healing | Increased | Decreased (70) | Not determined |

a References for data already published in the case of Vav family knockout mice are indicated in parentheses.

b Note that the lack of peripheral lymphocytes in triple Vav family knockout mice is probably due to ineffective development and positive selection of thymocytes (69).

Ahr Controls Vav3 Expression in the VLM

We have recently discovered that Vav3 is important for axon pathfinding events in the VLM (40), a region of the brainstem that controls respiratory activity and, via sympathetic efferents, several cardiovascular system components such as the heart, kidneys, subsets of adrenal chromaffin cells, and most classes of resistance arterioles. Because of this, this region is a key element in the regulation of blood pressure (41, 42). From a functional point of view, the VLM can be segregated in the rostral (RVLM) and caudal (CVLM) subregions that exert effector and regulatory roles, respectively (Fig. 4A) (41, 42, 57). The effector functions of the RVLM are controlled positively by glutamatergic signals derived from other brain areas that, in turn, receive and process information coming from peripheral baroreceptors (Fig. 4A). In addition, the RVLM is tonically inhibited by GABAergic signals derived from neurons present in the CVLM (Fig. 4A). In the case of Vav3−/− mice, we have found that axons from GABAergic CVLM neurons do not properly reach the RVLM, leading to loss of inhibitory GABAergic transmission and up-regulation of RVLM-dependent functions (40). To investigate whether a similar defect could be present in Ahr−/− mice, we first determined whether Ahr was expressed in the VLM and, if so, whether its knock-out led to alterations in Vav3 expression. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated that Ahr and Vav3 transcripts were present in the CVLM (Fig. 4, B and C). Moreover, we demonstrated by immunohistochemistry that Vav3 levels were reduced in Ahr−/− CVLMs (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Expression of Vav3 and Ahr in the CVLM. A, schematic representation of ventrolateral medulla regions, its synaptic interconnections, and regulatory functions. Inhibitory signals are indicated in red and as blunted lanes. Activation signals are indicated as arrows. Further details are found in the main text. B and C, representative examples of coronal brainstem sections containing the CVLM that were processed to detect the expression of the Vav3 (B and C, upper panel) and Ahr (C, lower panel) mRNAs by in situ hybridization. B, we indicated selected anatomical areas used for the localization of the CVLM (shaded in gray). Amb, nucleus ambiguus; CC, central canal; PY, pyramidal tract; Sp5I, spinal trigeminal nucleus interpolar; D, dorsal; V, ventral. The square shows the area considered to contain the CVLM. Scale bars, 1 mm. D, detection of Ahr mRNA by in situ hybridization (upper panel) and of Vav3 protein by immunohistochemical techniques (lower panels) in the CVLM of wild type (left panels) and Ahr−/− (right panels) mice. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Inhibitory GABAergic Signals Are Missing in the Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla of Ahr-deficient Mice

We surmised that the lack of proper Vav3 expression levels in the absence of Ahr could cause neurological defects in the VLM similar to those observed in Vav3 null mice (40). Using immunofluorescence techniques with antibodies to GABAergic axon terminal markers (GAD67, GAD65, and v-GAT), we found a 25–30% reduction in the total number of these presynaptic markers in the RVLM of Ahr−/− animals relative to the levels detected in control mice (Fig. 5, A and B). However, we did not observe any alteration in the expression of postsynaptic GABAA receptors in the same VLM area (Fig. 5, A and B). Similar results were observed in Vav3−/− mice (Fig. 4C) (40). Immunohistochemical analyses of serial sections also revealed that, similar to what happens in Vav3−/− animals (40), neurons located in the RVLM of Ahr−/− mice contained higher levels of tyrosine hydroxylase than those present in the RVLM of wild type mice (Fig. 5, C and D). This result demonstrates high levels of catecholaminergic activity in this brainstem area of Ahr-deficient mice, a result consistent with the reduction of inhibitory GABAergic synapses detected by the above immunofluorescence studies (see above and Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

Ahr and Vav3 gene deficiencies reduce the number of GABAergic signals in the RVLM. A, GAD67 (top panels), GAD65 (2nd panel from top), v-GAT (3rd panel from top), and GABAA receptor (GABA-R, bottom panels) immunoreactivity (red signals) in the RVLMs of wild type (left panels) and Ahr-deficient mice (right panels). Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue signals). Scale bar, 40 μm. B, intensity of signals for the indicated markers in RVLM sections from mice of the indicated genotypes (n = 3–5). *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.01 compared with control animals or the indicated experimental pair (in brackets). NS, not statistically significant. C, scheme of brainstem sections containing the RVLM (shaded in gray). Other areas used for histological analysis include the nucleus ambiguous (Amb), the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (LPGi), the pyramidal tract (PY), and the spinal trigeminal nucleus interpolar (Sp5I). Images taken from serial sections of the brainstem containing the RVLM were used for the anti-tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemical experiments shown in the next panel. D, tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity levels in coronal sections of the brainstem containing the RVLM from wild type (upper panels) and Ahr−/− (lower panels) mice. Sections were taken serially from a more rostral (left) to a more caudal (right) position within the RVLM. Scale bar, 80 μm.

To demonstrate the deficiency in inhibitory GABAergic transmission between the CVLM and RVLM of Ahr−/− mice, we carried out microinjection experiments in those two brainstem areas as previously done for Vav3−/− mice (40). The stereotaxic coordinates selected for the RVLM and CVLM in this work (see “Experimental Procedures”) were accurate, as demonstrated by the expected responses induced by microinjections of l-glutamate in the RVLM (increase in blood pressure and breathing frequency, see below and Fig. 6), CVLM (reduction in blood pressure and bradypnea, see below and Fig. 8, G, H, K, and L), and in an area outside the VLM (no effect on those two parameters, data not shown) of wild type mice.

FIGURE 6.

GABAergic signal defects in the RVLM of Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice. A, C, and E, example of representative recordings of the real time fluctuations of the blood pressure upon microinjecting bicuculline (B) and l-glutamate (G) in the RVLM of wild type (A, red color), Ahr- (C, blue color) and Vav3-deficient (E, green color) mice. The time of injection of each drug is indicated by arrows. Brackets (labeled 1–3) shown at the bottom of charts indicate the time intervals for the breathing recordings shown in B, D, and F, respectively. Intervals 2 and 3 were also used to measure the drug-induced arterial pressure shown in G. Scale bar, 2 min. B, D, and F, representative recordings of the variations of respiratory frequency of a wild type (B, red color), an Ahr−/− (D, blue color), and a Vav3−/− (F, green color) mouse at the times indicated in A, C, and E, respectively. G, arterial pressure levels in animals of the indicated genotypes microinjected in the RVLM with placebo (P), bicuculline (B), or l-glutamate (G) (n = 3–5). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with wild type controls. H, ventilation rates in mice of the indicated genotypes subjected to the microinjection protocol shown in B, D, and F (n = 3–5). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with wild type controls.

FIGURE 8.

GABAergic signal transmission defects from the CVLM to the RVLM of Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice. A–D, blood pressure (A and C) and breathing rate (B and D) changes occurring in a wild type (A and B, red color) and an Ahr−/− (C and D, blue color) mouse upon an unilateral microinjection of muscimol (M) in the RVLM using stereotaxic techniques. Time of microinjection is indicated by arrows. Brackets (labeled 1 to 2) shown at the bottom of charts in A and C indicate the time intervals for the breathing recordings shown in B and D, respectively. Segments 2 were also used to measure the drug-induced arterial pressure shown in E. Scale bar, 2 min. E and F, arterial pressure levels (E) and respiratory frequency values (F) detected in animals of the indicated genotypes microinjected in the RVLM with either placebo (P) or muscimol (M) (n = 3–5). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with placebo-treated wild type mice. G–J, representative real time recordings of blood pressure levels (G and I) and ventilation rates (H and J) of a wild type (G and H, red color) or an Ahr−/− (I and J, blue color) mouse upon bilateral microinjections of l-glutamate (G) within the CVLM. Time of microinjections is indicated by arrows. Brackets (labeled 1 to 2) shown at the bottom of charts present in G and I indicate the time intervals for the breathing recordings shown in H and J, respectively. Segments 2 were also used to measure the drug-induced arterial pressure shown in K. Scale bar, 2 min. K and L, average arterial pressure (K) and ventilation rates (L) in animals of the indicated genotypes microinjected in the CVLM with either placebo (P) or l-glutamate (G) (n = 3–5). **, p < 0.01 compared with wild type controls.

First, we used a GABAA receptor inhibitor (bicuculline) known to induce elevations of blood pressure and accelerated ventilation when microinjected in the RVLM. These effects are induced by the blockage of the tonic inhibitory GABA signaling in RVLM neurons (58). This antagonist induced the expected cardiovascular (Fig. 6A) and ventilation (Fig. 6B) responses when injected in RVLMs of wild type mice. By contrast, it did not cause any significant effect in any of those two systems when introduced in RVLMs of either Ahr−/− (Fig. 6, C and D) or Vav3−/− (Fig. 6, E and F) mice. A quantification of the effect of bicuculline in the blood pressure and respiratory cycles is shown in Fig. 6, G and H, respectively.

The subsequent administration of l-glutamate in the RVLM of wild type mice after the bicuculline treatment promoted the expected elevations in the blood pressure (Fig. 6A) and breathing frequency (Fig. 6B). This neurotransmitter also elicited hypertension (Fig. 6, C and E) and hyperventilation (Fig. 6, D and F) in Ahr−/− and Vav3−/− mice. Hypertension (Fig. 7, A, C, and E) and acceleration of breathing frequencies (Fig. 7, B, D and F) were also observed in Ahr−/− mice when l-glutamate was microinjected in the RVLM without prior introduction of bicuculline (Fig. 7). However, these time courses indicated that the high blood pressure and ventilation rates induced by l-glutamate lasted twice as long in microinjected Ahr−/− than in wild type mice (Fig. 7, compare A with C), further suggesting that they were not properly counterbalanced by negative GABAergic feedback signals. The enhanced response to l-glutamate was also observed in Vav3-deficient mice (40).

FIGURE 7.

Hypersensitivity of Ahr-deficient mice to l-glutamate injections in the RVLM. A–D, changes in blood pressure (A and C) and breathing rates (B and D) taking place in a wild type (A and B, red color) and an Ahr−/− (C and D, blue color) mouse upon a bilateral microinjection of l-glutamate (G) in the RVLM using stereotaxic techniques. Time of microinjection is indicated by arrows. Brackets (labeled 1 and 2) shown at the bottom of charts in A and C indicate the time intervals for the breathing recordings shown in B and D, respectively. Segments 2 were also used to measure the drug-induced arterial pressure shown in E. Scale bar, 2 min. E and F, arterial pressure levels (E) and respiratory frequency values (F) detected in animals of the indicated genotypes microinjected in the RVLM with either placebo (P) or l-glutamate (G) (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 compared with placebo-treated wild type mice.

In contrast to the bicuculline and l-glutamate microinjections, the administration of a GABA receptor agonist (muscimol) in the RVLM promoted hypotension and bradypnea responses in all animals under study independently of their genotype (Fig. 8, A–F). Taken together, these results indicate that the tonic GABAergic signaling, but not the GABAergic responses of postsynaptic receptors, is defective in both Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice.

Abnormal GABAergic Connectivity between the CVLM and RVLM

We have recently observed that the impaired GABAergic transmission in the VLM of Vav3−/− is caused by a defective wiring of the RVLM by axons coming from CVLM GABAergic neurons (40). To verify whether this defect was also present in Ahr−/− mice, we resorted again to the use of stereotaxic techniques to investigate the efficiency of GABAergic signal transmission from the CVLM to the RVLM. These experiments used as a main premise previous data indicating that the injection of l-glutamate in CVLM leads to the stimulation of GABAergic cells present in this region (59). As a result, the microinjection of this neurotransmitter in this brainstem area leads to hypotension and bradypnea due to enhanced inhibitory GABAergic signaling from l-glutamate-stimulated CVLM neurons. We observed that l-glutamate induced the expected physiological responses when introduced in the CVLM of wild type mice (Fig. 8, G and H). Instead, we did not record any significant effect of this neurotransmitter in blood pressure (Fig. 8I) and breathing rates (Fig. 8J) when microinjected in Ahr−/− mice. Similar results were observed when the same experiments were performed on Vav3−/− mice (40). A quantification of results obtained in these experiments is shown in Fig. 8, K and L. Collectively, these data indicate that GABAergic transmission between the CVLM and RVLM is impaired in Ahr−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have provided in vivo evidence that Vav3 is a bona fide Ahr transcriptional target. Thus, we have shown that specific tissues of Ahr−/− mice have low levels of expression of this Rho/Rac GDP/GTP exchange factor. Instead, the expression of other Vav family members whose genes lack XRE motifs in their promoter region remains unaffected by the Ahr loss of function. Furthermore, we have found that the cardiorespiratory phenotype of Ahr-deficient mice mimics closely that exhibited by mice carrying null Vav3 alleles. This work has also allowed us to expand the pathological portfolio present in Ahr-deficient mice. Thus, we report for the first time that these animals develop sympathoexcitation, hypertrophy, and hyperactivation of sympathetic chromaffin cells present in the adrenal gland medulla, tachycardia, and respiratory hyperventilation.

Further underscoring the relationship between Ahr and Vav3, our stereotaxic experiments have found quite equivalent GABAergic transmission defects from the CVLM to the RVLM in both Ahr- (this work) and Vav3-deficient mice (40). Although we have not dissected the biological mechanism underlying the VLM defects present in Ahr−/− mice, we surmise that they are probably caused by the defective wiring of the RVLM by axons emanating from CVLM GABAergic neurons as has been observed in Vav3-deficient mice (40). In agreement with this hypothesis, we have observed that Ahr−/− mice show reduced Vav3 protein levels in the CVLM and a significant reduction of presynaptic GABAergic markers (GAD67, GAD65, and v-GAT) in the RVLM. Thus, it is likely that the absence of Ahr will lead to Vav3-dependent cytoskeletal defects that, in the case of primary GABAergic neurons, are important for proper axon branching and growth cone morphology as well as for Ephrin-dependent axon collapsing responses in GABAergic cells (40). A Vav3-dependent cytoskeletal phenotype in Ahr−/− MEFs has been described by us before (35). To our knowledge, this is the first neurological defect reported for any mammalian Ahr protein. However, it is worth noting that previous reports have indicated that Ahr-1 and Spineless, the single Ahr family members present in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, regulate lineage determination events, migration, and/or dendritogenesis in a number of neuronal subsets (60–62).

The highly similar profile of cardiovascular, respiratory, and sympathetic defects found in Ahr- and Vav3-deficient mice suggests that the hypertension phenotype described earlier in Ahr−/− mice (27) is caused by the defective wiring of the VLM. This is the case in Vav3−/− mice, because we did not find any other defect in their peripheral vasculature so far (40). Furthermore, we have previously shown that the chronic administration of propranolol, a β-adrenergic receptor antagonist, blocks the development of hypertension, the activation of the renin/angiotensin system, the cardiovascular remodeling, and the tissue fibrosis found in Vav3−/− animals (38). However, given the extensive implication of Ahr in embryonic and neonatal vascular development, we cannot exclude the possibility that other Vav3-independent defects could contribute to the evolution of the cardiovascular pathologies found in Ahr-deficient mice. For example, it has been described that Ahr is important for vasculogenesis, a process that may contribute to alterations in peripheral vascular resistance if not working properly (63). It has been also proposed that the Ahr deficiency may promote hypertension by defective fluid shear stress responses in arterioles (64). However, these defects cannot explain the rest of the sympathetic and respiratory changes seen in Ahr-deficient mice. In any case, the defective cardiovascular responses observed in our stereotaxic experiments suggest that the VLM defects probably play a major role in the cardiovascular phenotype of the mice. Formal resolution of this issue will entail the generation of tissue-specific Ahr gene knockouts in endothelial, vascular smooth muscle cells, and the VLM.

The data shown in this work also indicate that the loss of Vav3 is not involved in the hepatic, skin, and reproductive system defects developed by Ahr−/− mice. This is not due to compensation events by other Vav family members, because the compound Vav1−/−;Vav2−/−;Vav3−/− knock-out mice do not develop Ahr−/−-like phenotypes in those tissues. However, given that Vav3 expression is lost in many tissues from Ahr-deficient mice, we cannot rule out that it could be involved in additional defects present in specific cell types of those tissues. Further work with these two mouse strains will shed further light on the specific contribution of Vav3 to all Ahr-dependent physiological events.

Despite the clear correlation between Ahr and Vav3 expression in tissues, we have observed that the addition of xenobiotics either in culture (35) or in animals (this work) does not increase the levels of Vav3 mRNA. This indicates that, unlike the case of many Ahr transcriptional targets, the effect of Ahr on the Vav3 proto-oncogene is ligand-independent. Previous results suggest however that this functional relationship entails the prototypical interaction of transcriptional factors with the promoter region of the target gene. Thus, we have observed using ChIP analysis that Ahr binds to one of the XRE-binding sites present in the Vav3 promoter (35). Furthermore, luciferase reporter assays have shown that this XRE motif is required for the effective transcriptional activation of the Vav3 gene by Ahr (35). Ligand-independent Ahr functions have been shown before in the regulation of TGF-β (18), Slug (19), and c-Myc (20). The mechanism that regulates this ligand-independent function of Ahr is unknown, although recent data indicate that this protein can be either up- or down-regulated by different biological and signaling stimuli, including high cell density (65), shear stress (66), calcium levels (19), protein-tyrosine kinases (67), or G-coupled receptors (68). Interestingly, the Ahr homologues present in invertebrates do not bind xenobiotics (21, 22), suggesting that these ligand-independent functions could represent the most ancient functional strata of Ahr family proteins.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01CA073735. This work was also supported by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grants SAF2009-07172 and RD06/0020/0001, Castilla y León Autonomous Government Grant GR97, and the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (to X. R. B.), Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grants SAF2008-00462 and RD06/0020/1016, and Junta de Extremadura Grants GRU08012 and GRU09001 (to P. F.-S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- Ahr

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AngII

- angiotensin II

- CVLM

- caudal ventrolateral medulla

- GABA

- γ-aminobutyric acid

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- RVLM

- rostral ventrolateral medulla

- SNS

- sympathetic nervous system

- VLM

- ventrolateral medulla

- XRE

- xenobiotic responsive element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Denison M. S., Nagy S. R. (2003) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 309–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pascussi J. M., Gerbal-Chaloin S., Duret C., Daujat-Chavanieu M., Vilarem M. J., Maurel P. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48, 1–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barouki R., Coumoul X., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 3608–3615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Mimura J. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kimura S., Gonzalez F. J., Nebert D. W. (1986) Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 1471–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gonzalez F. J., Nebert D. W. (1985) Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 7269–7288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Savas U., Bhattacharyya K. K., Christou M., Alexander D. L., Jefcoate C. R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14905–14911 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sutter T. R., Tang Y. M., Hayes C. L., Wo Y. Y., Jabs E. W., Li X., Yin H., Cody C. W., Greenlee W. F. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13092–13099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen Z., Liu J., Wells R. L., Elkind M. M. (1994) DNA Cell Biol. 13, 763–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leung Y. K., Ho J. W. (2002) Biochem. Pharmacol. 63, 767–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Münzel P. A., Schmohl S., Buckler F., Jaehrling J., Raschko F. T., Köhle C., Bock K. W. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Auyeung D. J., Kessler F. K., Ritter J. K. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sato S., Shirakawa H., Tomita S., Ohsaki Y., Haketa K., Tooi O., Santo N., Tohkin M., Furukawa Y., Gonzalez F. J., Komai M. (2008) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 229, 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fletcher N., Wahlstrom D., Lundberg R., Nilsson C. B., Nilsson K. C., Stockling K., Hellmold H., Hakansson H. (2005) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 207, 1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boverhof D. R., Burgoon L. D., Tashiro C., Chittim B., Harkema J. R., Jump D. B., Zacharewski T. R. (2005) Toxicol. Sci. 85, 1048–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sutter T. R., Guzman K., Dold K. M., Greenlee W. F. (1991) Science 254, 415–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marlowe J. L., Puga A. (2005) J. Cell. Biochem. 96, 1174–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang X., Fan Y., Karyala S., Schwemberger S., Tomlinson C. R., Sartor M. A., Puga A. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6127–6139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikuta T., Kawajiri K. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 3585–3594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang X., Liu D., Murray T. J., Mitchell G. C., Hesterman E. V., Karchner S. I., Merson R. R., Hahn M. E., Sherr D. H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 7869–7881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Powell-Coffman J. A., Bradfield C. A., Wood W. B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2844–2849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butler R. A., Kelley M. L., Powell W. H., Hahn M. E., Van Beneden R. J. (2001) Gene 278, 223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abbott B. D., Schmid J. E., Pitt J. A., Buckalew A. R., Wood C. R., Held G. A., Diliberto J. J. (1999) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 155, 62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baba T., Mimura J., Nakamura N., Harada N., Yamamoto M., Morohashi K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10040–10051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernandez-Salguero P., Pineau T., Hilbert D. M., McPhail T., Lee S. S., Kimura S., Nebert D. W., Rudikoff S., Ward J. M., Gonzalez F. J. (1995) Science 268, 722–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mimura J., Yamashita K., Nakamura K., Morita M., Takagi T. N., Nakao K., Ema M., Sogawa K., Yasuda M., Katsuki M., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1997) Genes Cells 2, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lund A. K., Goens M. B., Kanagy N. L., Walker M. K. (2003) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 193, 177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt J. V., Su G. H., Reddy J. K., Simon M. C., Bradfield C. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6731–6736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lahvis G. P., Pyzalski R. W., Glover E., Pitot H. C., McElwee M. K., Bradfield C. A. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corchero J., Martín-Partido G., Dallas S. L., Fernández-Salguero P. M. (2004) Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 85, 295–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Santiago-Josefat B., Mulero-Navarro S., Dallas S. L., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gomez-Duran A., Ballestar E., Carvajal-Gonzalez J. M., Marlowe J. L., Puga A., Esteller M., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carvajal-Gonzalez J. M., Roman A. C., Cerezo-Guisado M. I., Rico-Leo E. M., Martin-Partido G., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 1823–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andreola F., Hayhurst G. P., Luo G., Ferguson S. S., Gonzalez F. J., Goldstein J. A., De Luca L. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3434–3438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carvajal-Gonzalez J. M., Mulero-Navarro S., Roman A. C., Sauzeau V., Merino J. M., Bustelo X. R., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1715–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Movilla N., Bustelo X. R. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7870–7885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bustelo X. R. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1461–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sauzeau V., Sevilla M. A., Rivas-Elena J. V., de Alava E., Montero M. J., López-Novoa J. M., Bustelo X. R. (2006) Nat. Med. 12, 841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quevedo C., Sauzeau V., Menacho-Márquez M., Castro-Castro A., Bustelo X. R. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1125–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sauzeau V., Horta-Junior J. A., Riolobos A. S., Fernandez G., Sevilla M. A., Lopez D. E., Montero M. J., Rico B., Bustelo X. R. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 4251–4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guyenet P. G. (2006) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thrasher T. N. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 288, R819–R827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turner M., Billadeau D. D. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 476–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cowan C. W., Shao Y. R., Sahin M., Shamah S. M., Lin M. Z., Greer P. L., Gao S., Griffith E. C., Brugge J. S., Greenberg M. E. (2005) Neuron 46, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sauzeau V., Jerkic M., López-Novoa J. M., Bustelo X. R. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 943–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turner M., Mee P. J., Walters A. E., Quinn M. E., Mellor A. L., Zamoyska R., Tybulewicz V. L. (1997) Immunity 7, 451–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Doody G. M., Bell S. E., Vigorito E., Clayton E., McAdam S., Tooze R., Fernandez C., Lee I. J., Turner M. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sauzeau V., Sevilla M. A., Montero M. J., Bustelo X. R. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 315–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jerkic M., Rivas-Elena J. V., Prieto M., Carrón R., Sanz-Rodríguez F., Pérez-Barriocanal F., Rodríguez-Barbero A., Bernabéu C., López-Novoa J. M. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 609–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chevillard C., Brown N. L., Mathieu M. N., Laliberté F., Worcel M. (1988) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 147, 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Flores O., Arévalo M., Gallego B., Hidalgo F., Vidal S., López-Novoa J. M. (1998) Exp. Nephrol. 6, 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ema M., Sogawa K., Watanabe N., Chujoh Y., Matsushita N., Gotoh O., Funae Y., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 184, 246–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Frankin B. J., Paxinos G. T. (1996) The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 54. Carrasco G. A., Van de Kar L. D. (2003) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 463, 235–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lifton R. P., Gharavi A. G., Geller D. S. (2001) Cell 104, 545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Molinoff P. B., Axelrod J. (1971) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 40, 465–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Blessing W. W. (1988) Am. J. Physiol. 254, H686–H692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yoshida S., Matsubara T., Uemura A., Iguchi A., Hotta N. (2002) Circ. J. 66, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tolentino-Silva F. P., Haxhiu M. A., Ernsberger P., Waldbaum S., Dreshaj I. A. (2000) J. Appl. Physiol. 89, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim M. D., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 2806–2819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Qin H., Powell-Coffman J. A. (2004) Dev. Biol. 270, 64–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Huang X., Powell-Coffman J. A., Jin Y. (2004) Development 131, 819–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lahvis G. P., Lindell S. L., Thomas R. S., McCuskey R. S., Murphy C., Glover E., Bentz M., Southard J., Bradfield C. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10442–10447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McMillan B. J., Bradfield C. A. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ikuta T., Kobayashi Y., Kawajiri K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19209–19216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mufti N. A., Bleckwenn N. A., Babish J. G., Shuler M. L. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208, 144–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Backlund M., Ingelman-Sundberg M. (2005) Cell. Signal. 17, 39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nakata A., Urano D., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Mizuno N., Tago K., Itoh H. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 622–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fujikawa K., Miletic A. V., Alt F. W., Faccio R., Brown T., Hoog J., Fredericks J., Nishi S., Mildiner S., Moores S. L., Brugge J., Rosen F. S., Swat W. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 1595–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sindrilaru A., Peters T., Schymeinsky J., Oreshkova T., Wang H., Gompf A., Mannella F., Wlaschek M., Sunderkötter C., Rudolph K. L., Walzog B., Bustelo X. R., Fischer K. D., Scharffetter-Kochanek K. (2009) Blood 113, 5266–5276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.