Abstract

FimX is a multidomain signaling protein required for type IV pilus biogenesis and twitching motility in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FimX is localized to the single pole of the bacterial cell, and the unipolar localization is crucial for the correct assembly of type IV pili. FimX contains a non-catalytic EAL domain that lacks cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) phosphodiesterase activity. It was shown that deletion of the EAL domain or mutation of the signature EVL motif affects the unipolar localization of FimX. However, it was not understood how the C-terminal EAL domain could influence protein localization considering that the localization sequence resides in the remote N-terminal region of the protein. Using hydrogen/deuterium exchange-coupled mass spectrometry, we found that the binding of c-di-GMP to the EAL domain triggers a long-range (∼ca. 70 Å) conformational change in the N-terminal REC domain and the adjacent linker. In conjunction with the observation that mutation of the EVL motif of the EAL domain abolishes the binding of c-di-GMP, the hydrogen/deuterium exchange results provide a molecular explanation for the mediation of protein localization and type IV pilus biogenesis by c-di-GMP through a remarkable allosteric regulation mechanism.

Keywords: Bacterial Signal Transduction, Cyclic Nucleotides, Ligand-binding Protein, Prokaryotic Signal Transduction, Protein Structure, Allosteric Regulation, c-di-GMP, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Twitching Motility, Type IV Pili

Introduction

The emergence of the cyclic dinucleotide c-di-GMP2 as a major signaling molecule in bacteria has unveiled a previously hidden signaling network that controls a variety of cellular functions that contribute to bacterial pathogenicity (1, 2). The c-di-GMP network is usually composed of signaling proteins and riboswitches for c-di-GMP synthesis, degradation, and recognition (3). EAL and GGDEF domain-containing proteins are the most prevalent c-di-GMP signaling proteins, with the canonical GGDEF and EAL domains functioning as diguanylate cyclases for c-di-GMP synthesis and phosphodiesterases for c-di-GMP degradation, respectively (4–6). Recent studies have, however, uncovered a significant number of degenerate or non-catalytic GGDEF and EAL domains (5, 7–14). The discovery of the non-catalytic GGDEF and EAL domains adds another layer of complexity to the c-di-GMP signaling network that has yet to be fully understood.

Recent identification of the catalytic residues for the EAL domain phosphodiesterases led to the realization that 20–25% of the EAL domains encoded by the bacterial genomes are catalytically incompetent due to the absence of key catalytic residues (7, 15). FimX is a cytoplasmic protein (76 kDa) required for normal twitching motility and biofilm formation in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (16, 17). Although the EAL domain of FimX was first suggested to function as a phosphodiesterase domain, it was later established to be a non-catalytic domain (7, 16, 18). Recent studies from Sondermann and co-workers (18) have demonstrated that the EAL domain of P. aeruginosa FimX binds c-di-GMP with high affinity. The crystal structure of the stand-alone EAL domain in complex with c-di-GMP determined by the same group reveals the binding of c-di-GMP without the assistance of metal ion. Farah and co-workers (19) reported that the EAL domain of the FimX homolog in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri not only binds c-di-GMP but also interacts directly with the PilZ protein, a key protein in type IV pilus biogenesis. In addition to the EAL domain, FimX contains three other protein domains that include a CheY or REC (phosphoreceiver-like) domain, a PAS (Per/ARNT/Sim) domain, and a GGDEF domain (Fig. 1). The functions of the three domains remain unknown despite the overall sequence similarity shared with other homologous domains. Notably, the defective REC domain is unlikely to function as an archetypal phosphoreceiver domain because it lacks an essential Asp residue for phosphorylation.

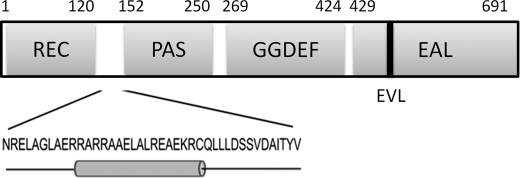

FIGURE 1.

Domain organization of FimX. The sequence and predicted secondary structure of the linker region between the PAS and REC domains are highlighted.

Mattick and co-workers (20) first reported that GFP-tagged FimX adopts a unipolar localization in P. aeruginosa. The cellular localization of FimX was shown to be critical for the function of FimX in the assembly of unipolar type IV pili (16, 20). In vivo studies demonstrated that the N-terminal REC domain and the adjacent linker region are indispensible for retaining the unipolar localization of FimX, indicating that the localization sequence resides in the N-terminal region (16, 20). It is puzzling that deletion of the EAL domain or mutation of the signature EVL motif of the EAL domain has a dramatic effect on protein localization by greatly reducing the probability of the protein to adopt the unipolar distribution (16). A molecular mechanism that can rationalize the in vivo observation is still lacking. In this study, we examined FimX using the method of amide hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange-coupled mass spectrometry. The highly sensitive H/D exchange method revealed that the binding of c-di-GMP to the EAL domain triggers a distinctive conformational change in the REC domain and the adjacent linker region. Binding assays demonstrated that mutation of the EVL motif completely abolishes the c-di-GMP-binding capability of FimX. Together, the results provide a novel molecular explanation for the mediation of protein function and cellular location by c-di-GMP through an allosteric regulation mechanism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The chemicals and biological reagents used for protein cloning and expression were obtained from common commercial sources. c-di-GMP was synthesized enzymatically using a thermophilic diguanylate cyclase protein as described previously (21, 22).

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Proteins

The gene encoding full-length FimX was amplified from the genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa PAO1. The gene fragment was cloned into the expression vector pET-26b(+) (Novagen) between the NdeI and NotI restriction sites. The DNA fragment that encodes the EAL domain (FimX-(436–691)) was cloned into the expression vector pET-28a(+) between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The plasmid harboring the gene construct and the His6 tag-encoding sequence was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3). For protein expression, 2 ml of culture inoculated by the cell stock was added to 1 liter of LB medium. The bacterial culture was grown at 37 °C up to A = 0.8 before induction with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 16 °C for 16 h. The harvested cell pellet was lysed with 40 ml of lysis buffer containing 50 mm NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0), 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 mm imidazole. After centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatants were filtered and then incubated with 2 ml of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) for 30 min. The resin was washed with 50 ml of wash buffer (lysis buffer with 50 mm imidazole). The protein was eluted with elution buffer (lysis buffer with 300 mm imidazole). Fractions with a purity of >95% were pooled together after SDS-PAGE analysis. Size-exclusion chromatography was carried out at 4 °C using the ÄKTA FPLC system equipped with a Superdex 200 HR 16/60 column (GE Healthcare). Because c-di-GMP was found to be copurified with FimX, the protein solution was treated with the c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase RocR and Mg2+ to remove c-di-GMP (7). The ligand-free protein used in this study was subsequently separated from RocR by size-exclusion chromatography. Purified protein was flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C after measurement of the concentration. The mutant was generated using the Stratagene site-directed mutagenesis II kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mutant protein was expressed and purified following the same procedure.

Amide H/D Exchange by Mass Spectrometry

The experimental setup for H/D exchange was similar to the one described previously (23–26). Prior to H/D exchange, FimX was exchanged into 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 100 mm sodium chloride and 2 mm DTT. The peptides generated by pepsin digestion were first identified by MS/MS. The H/D exchange reactions were initiated by the addition of 10 μl of newly thawed protein solution to 90 μl of D2O. After incubation for various lengths of time (10 s, 1, 5, 20, 40, 60, and 90 min), the exchange reaction was rapidly quenched by lowering the pH to 2.4 and the temperature to 0 °C, followed by pepsin digestion. The generated peptides were passed through a homemade capillary reverse-phase C-18 HPLC column and eluted into an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 20 μl/min using a stepped gradient (7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, 25, 30, 40, and 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid). The time from initiation of digestion to elution of the last peptide was ∼25 min. Xcalibur software was used for spectrum analysis and data extraction, and the H/D exchange data were processed using the program HX-Express (27). Measured peptide masses were corrected for artifactual in-exchange and back-exchange following the methods described by Hoofnagle et al. (23). The time-dependent H/D exchange data were fit by nonlinear regression method as described previously (26).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The dissociation constants (Kd) and stoichiometric ratio for the interaction between FimX and c-di-GMP were measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) using an ITC200 calorimeter (MicroCal). Calorimetric titration of c-di-GMP (1 mm in the syringe; 0.5-μl injections) and full-length FimX or FimX mutants (40 μm in the cell) was performed at 25 °C in assay buffer containing 10 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and 100 mm NaCl. A time spacing of 240 s was set between injections. ITC data were analyzed by integrating the heat effects after being normalized to the amount of injected protein. Data fitting was based on a single-site binding model using the embedded software package (MicroCal) to obtain the dissociation constants.

Structural Modeling

The structural model of the REC domain was constructed by homology modeling. The model of FimX was built by incorporating the model of the REC domain into the original FimX model obtained from Sondermann and co-workers (18) with the helix linker between the REC and PAS domains arbitrarily positioned.

RESULTS

Effect of c-di-GMP Binding by Amide H/D Exchange

The binding of c-di-GMP by FimX does not induce a change in global structure or oligomeric state because the free and c-di-GMP-bound FimX proteins appear to be almost identical in solution scattering and analytic ultracentrifugation analysis (18). We postulated that the effect of c-di-GMP binding might be exerted through a local conformational change that was undetectable by the scattering and sedimentation methods. Amide H/D exchange by mass spectrometry is a highly sensitive technique for detecting ligand binding and conformational change in native proteins by monitoring the incorporation of deuterons (23). We reasoned that H/D exchange by mass spectrometry would be an ideal tool for detecting small local conformational changes in FimX.

H/D exchange by mass spectrometry was performed following an established protocol (23–26). The peptides generated by pepsin digestion were identified by a MS/MS experiment. H/D exchange of FimX was conducted in the absence and presence of 10 μm c-di-GMP. A total of 38 peptides that encompass 88% of the protein sequence were chosen for data analysis (Fig. 2). The deuteration patterns of every peptide in the absence and presence of c-di-GMP were compared by examining the time-dependent deuteration profiles. Overall, 30 of the 38 peptides exhibited almost identical H/D exchange patterns (supplemental Fig. S1). Statistically significant exchange patterns were observed only for eight peptides in repeated experiments. The eight peptides are found exclusively in the EAL domain, the REC domain, and the adjacent linker region as discussed below.

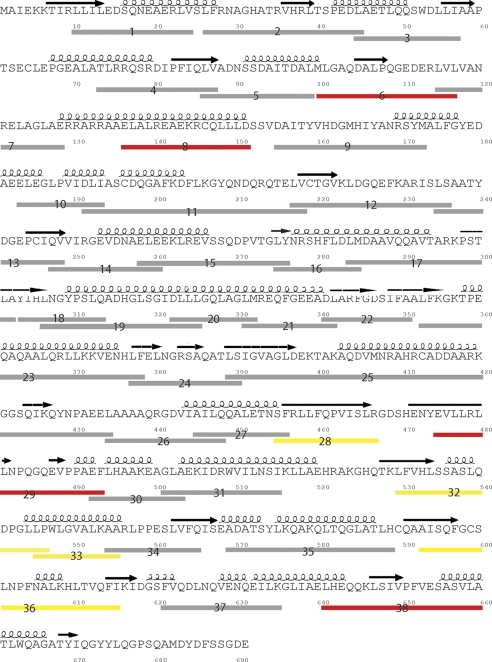

FIGURE 2.

Sequence coverage map of FimX. The peptides include peptides 1–8 from the REC domain and the adjacent linker, peptides 9–14 from the PAS domain, peptides 15–26 from the GGDEF domain, and peptides 27–38 from the EAL domain. The peptides used for analysis of deuteration patterns are represented by bars. The red and yellow bars represent peptides with large and moderate changes in deuteration upon binding c-di-GMP, whereas the gray bars represent peptides without significant changes in deuteration.

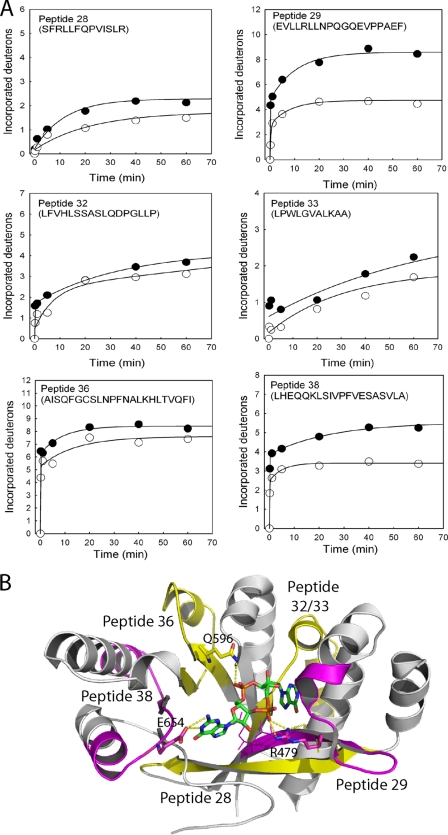

In the EAL domain, six peptides exhibited reduced levels of deuteration, indicating a decreased solvent accessibility for the six peptides upon c-di-GMP binding (Fig. 3A). The six peptides were mapped onto the crystal structure of the c-di-GMP-bound EAL domain of FimX (Protein Data Bank code 3HV8) (Fig. 3B). Peptides 29 and 38 exhibited the greatest suppression in deuteration. The crystal structure shows that both peptides contain residues that are in direct contact with the guanine moiety of c-di-GMP. In addition, Arg479 of peptide 29 is involved in charge-charge interaction with the phosphate group. Peptide 29 also harbors the signature motif EVL and a short helix that was seen to undergo a rigid body shift upon c-di-GMP binding (18). Minor suppression of deuteration was observed for four peptides (peptides 28, 32, 33, and 36) in the EAL domain. Peptide 28 consists of the first β strand of the central barrel, whereas peptides 33 and 36 contain β strands and loops from the c-di-GMP-binding pocket. A small reduction in deuteration was observed for peptide 32, which is the only peptide that does not make direct contact with c-di-GMP. In the crystal structure of the stand-alone EAL domain, the N-terminal helix (α0) becomes unstructured upon c-di-GMP binding (18). No difference in deuteration was observed between the free and c-di-GMP-bound forms of the α0 helix-containing peptide 27 (supplemental Fig. S1), indicating that the secondary structure of the helix does not change in full-length FimX.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of c-di-GMP binding on the deuteration patterns of the peptides in the EAL domain of FimX. A, time courses of H/D exchange for the six peptides that exhibited altered deuteration upon c-di-GMP binding. ●, 0 μm c-di-GMP; ○, 10 μm c-di-GMP. B, crystal structure of the FimX EAL domain in complex with c-di-GMP (Protein Data Bank code 3HV8). The peptides that exhibited large and moderate changes in deuteration upon binding c-di-GMP (stick model) are colored magenta and yellow, respectively. The residues involved in hydrogen bonding or charge-charge interaction are shown as sticks. The residues of the EVL motif are shown as lines.

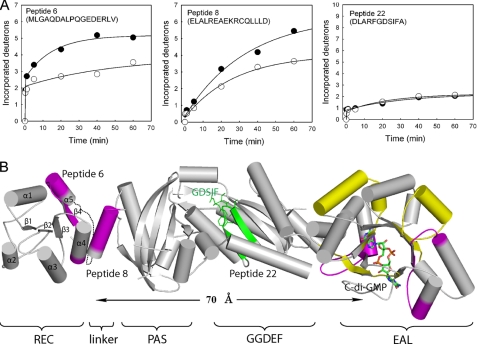

In contrast to the EAL domain, none of the peptides in the adjacent GGDEF and PAS domains showed significant change in deuteration. For instance, the exchange profile for the peptide (peptide 22) that contains the GDSIF motif in the GGDEF domain revealed that only two amide hydrogens were substituted with deuterons during H/D exchange regardless of the presence of c-di-GMP (Fig. 4A). The lack of changes indicates that c-di-GMP binding has little effect on the conformation or flexibility of the GGDEF and PAS domains. In contrast, two peptides from the N-terminal REC domain and the adjacent linker exhibited reduction in deuteration upon c-di-GMP binding (Fig. 4A). One peptide (peptide 6) resides in the REC domain, and the other (peptide 8) resides in the linker region (Fig. 4B). Peptide 6 contains the α5 helix, the β4 strand, and part of the α4 helix and constitutes most of the α4-β4-α5 face that is known as the interaction surface for CheY-like proteins. Peptide 8 consists of part of the predicted long helix linker between the REC and PAS domains. The orientation of the REC domain and the position of peptide 8 are arbitrary in the structural model shown in Fig. 3B because the full-length FimX or REC domain structure is unavailable at this moment. Interestingly, the gradual incorporation of deuterons observed for peptide 8 is indicative of cooperative or collective protein motions for the helix linker. The suppressed deuteration levels upon c-di-GMP binding for peptides 6 and 8 indicate a decrease in solvent accessibility in the region containing the two peptides, likely due to a conformational change as discussed below.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of c-di-GMP binding on the deuteration patterns of the peptides in FimX. A, time courses of H/D exchange are shown for peptides 6, 8, and 22 at 0 μm c-di-GMP (●) and 10 μm c-di-GMP (○). B, structural model of FimX. The regions that exhibited large or moderate changes in deuteration are colored magenta and yellow, respectively. The peptide that contains the GDSIF motif in the GGDEF domain is colored green.

Effect of Mutation of the EVL Motif on c-di-GMP Binding

In vivo studies showed that the N-terminal REC domain and the adjacent linker region harbor the protein sequence that is indispensible for the unipolar localization of FimX (16, 20). Intriguingly, Kazmierczak et al. (16) observed that mutation of the E475V476L477 motif to AAA in the EAL domain dramatically alters the unipolar localization of FimX, with the triple-mutant protein more likely adopting a bipolar or non-polar distribution. Overexpression of the mutant protein in the ΔfimX strain also failed to restore twitching motility (16). In the crystal structure of the FimX EAL domain complexed with c-di-GMP, c-di-GMP is bound in the pocket through the interaction with several polar and non-polar residues that include Tyr673, Glu654, Asp507, Arg479, and Leu477 (18). The EVL motif may contribute to c-di-GMP binding because Leu477 makes direct contact with the ribose and guanine moiety and Glu475 interacts with c-di-GMP indirectly through a water-mediated hydrogen bond network.

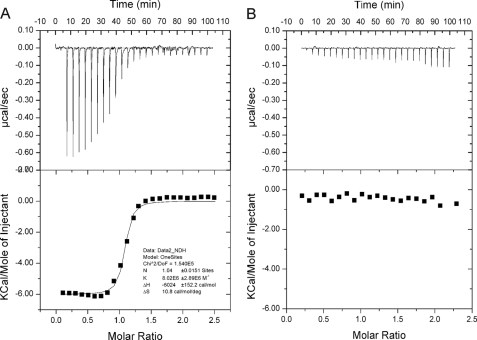

Given the structural information and the conformational change induced by c-di-GMP as suggested by the H/D exchange results, we further examined whether the effect of the EVL-to-AAA mutation is due to the perturbation of c-di-GMP binding. A binding assay by ITC was conducted to compare wild-type FimX and the AAA triple mutant. Full-length FimX binds c-di-GMP with a Kd of 0.12 ± 0.03 μm (Fig. 5), which is close to the reported Kd of 125 nm (18). Remarkably, the triple mutation reduced the binding affinity for c-di-GMP drastically, with no significant binding observed for the mutant under the experimental conditions in which the final concentration of c-di-GMP reached 100 μm. The disastrous effect of the mutation on the binding is surprising considering that the key residues (Arg479 and Glu654) for c-di-GMP binding remained in place. At the same time, the lack of c-di-GMP binding for the mutant also confirms that FimX possesses only a single c-di-GMP-binding site in the EAL domain.

FIGURE 5.

ITC analysis of the contribution of the EVL motif to c-di-GMP binding. A, isotherm for the binding of c-di-GMP by FimX. B, isotherm for the binding of c-di-GMP by the EVL-to-AAA triple mutant. DoF, degrees of freedom; deg, degrees.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the structures of the free and c-di-GMP-bound FimX EAL domains suggested that the EAL domain does not undergo large conformational changes upon ligand binding (18). The decreases in solvent accessibility in the EAL domain upon c-di-GMP binding are thus likely caused by direct protein-ligand interaction. The largest decreases are seen in the peptides that form hydrogen bonds with c-di-GMP, consistent with the idea that formation of hydrogen bonds between the protein and ligand can impede H/D exchange. The abolishment of the binding of c-di-GMP by mutation of the EVL motif to AAA reveals the critical roles of the three residues and local structure for c-di-GMP recognition. Considering the highly similar c-di-GMP-binding mode shared by EAL domains, such a critical role of the EAL or EVL motif in c-di-GMP binding may be common for EAL domains.

The most striking observation of this study is the change in solvent accessibility in the REC domain and the adjacent linker region upon binding of c-di-GMP. ITC experiments with full-length FimX and the AAA triple mutant confirmed that FimX harbors only a single c-di-GMP-binding site in the EAL domain. Thus, the altered solvent accessibility cannot be attributed to the direct binding of c-di-GMP in this region but is most likely due to a long-range conformational change triggered by c-di-GMP binding in the EAL domain. The observation is remarkable because the location of the conformational change is ∼70 Å away from the c-di-GMP-binding site, and no significant changes are seen in the intervening PAS and GGDEF domains. How the binding signal is transmitted over such a long distance in FimX remains an intriguing question for future exploration. It should be noted that the data can also be accommodated by a classic allosteric model that assumes the pre-existence of two discrete conformations for ligand-free FimX. The binding of the ligand c-di-GMP may just shift the equilibrium toward one of the conformations.

Regardless of the nature of signal propagation, the allosteric effect of c-di-GMP binding suggests a mechanistic link between the in vitro and in vivo observations from previous studies and provides an explanation for the mediation of the cellular localization of FimX by c-di-GMP. We propose that the binding of c-di-GMP induces a local conformational change in the region that encompasses most of the α4-β5-α5 face and the helix linker. Such a conformational change could impede the binding of FimX to its partner, a protein that is putatively localized to the single pole as suggested previously (16, 20). Instead of acting as a phosphoreceiver domain, the defective REC domain of FimX would function as an effector domain for the interaction with its partner through the α4-β5-α5 face and the adjacent helix. Alternatively, the α4-β5-α5 face may be part of the dimerization interface of FimX as proposed by Sondermann et al. (18), and the binding to the partner could be mediated solely by the helix linker. In this case, the change in deuteration may also result from a change in the subunit-subunit contact within the dimeric protein, possibly through a rotation of the REC domain. The postulated role of the α4-β5-α5 face in hetero- or homoprotein-protein interaction is not unprecedented considering the common role of the α4-β5-α5 surface in mediating intra- or interprotein interaction for CheY-like domain proteins (28–31). Note that although we did not observe a change in oligomeric structure upon c-di-GMP binding under the experimental conditions, the in vitro observations cannot totally rule out the possibility that c-di-GMP binding may affect higher order oligomer formation in the cells where other protein partners are present and high local FimX concentration may be attained at the pole of the bacterial cell. With the postulated effect of c-di-GMP binding on the interaction between FimX and its protein partners or protein oligomerization, it can be rationalized why deletion of the EAL domain (or mutation of the EVL motif) negatively affects the localization of FimX to the single pole for the correct assembly of type IV pili.

Mediation of bacterial motility through the interaction between flagellar proteins and the c-di-GMP-binding proteins YcgR and DgrA in E. coli, Salmonella, and Caulobacter crescentus has been established recently (32–35). The binding of YcgR and DgrA to their partners is highly dependent on the concentration of the local c-di-GMP pool. The results presented here suggest that c-di-GMP may also act in a similar fashion as an allosteric regulator controlling the binding of FimX to its partner in the mediation of the assembly of type IV pili and twitching motility. In contrast to YcgR and DgrA, which contain a PilZ domain for c-di-GMP binding, FimX proteins employ the non-catalytic EAL domain as the c-di-GMP-binding domain. The role of the non-catalytic EAL domain as a c-di-GMP-binding domain is also reminiscent of the role of the EAL domain of LapD, a Pseudomonas fluorescens protein that senses cellular c-di-GMP levels with its cytoplasmic EAL domain and modulates the function of the output domain in the periplasmic space (8). LapD and FimX thus represent an increasing number of EAL domain proteins that have lost the c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity and evolved to function as regulatory domains for binding the allosteric regulator c-di-GMP. Given that 20–25% of the EAL domains encoded by sequenced bacterial genomes are estimated to be catalytically inactive, the use of the non-catalytic EAL domain as a c-di-GMP-binding domain for the regulation of catalytic or binding function of the output domain through an allosteric mechanism may be a rather common phenomenon.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Holger Sondermann for providing the structural model of FimX.

This work was supported by Biomedical Research Council Grant 06/1/22/19/464 (to Z.-X. L.) and University Research Council Grant RG62/06 (to K. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- c-di-GMP

- cyclic diguanylate

- H/D

- hydrogen/deuterium

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry.

REFERENCES

- 1. Römling U., Gomelsky M., Galperin M. Y. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 57, 629–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hengge R. (2009) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schirmer T., Jenal U. (2009) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 724–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ryjenkov D. A., Tarutina M., Moskvin O. V., Gomelsky M. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 1792–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schmidt A. J., Ryjenkov D. A., Gomelsky M. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 4774–4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tamayo R., Tischler A. D., Camilli A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33324–33330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao F., Yang Y., Qi Y., Liang Z. X. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 3622–3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newell P. D., Monds R. D., O'Toole G. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3461–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tschowri N., Busse S., Hengge R. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 522–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christen B., Christen M., Paul R., Schmid F., Folcher M., Jenoe P., Meuwly M., Jenal U. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32015–32024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duerig A., Abel S., Folcher M., Nicollier M., Schwede T., Amiot N., Giese B., Jenal U. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 93–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rao F., See R. Y., Zhang D., Toh D. C., Ji Q., Liang Z. X. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 473–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki K., Babitzke P., Kushner S. R., Romeo T. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 2605–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qi Y., Rao F., Luo Z., Liang Z. X. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 10275–10285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barends T. R., Hartmann E., Griese J. J., Beitlich T., Kirienko N. V., Ryjenkov D. A., Reinstein J., Shoeman R. L., Gomelsky M., Schlichting I. (2009) Nature 459, 1015–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kazmierczak B. I., Lebron M. B., Murray T. S. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 60, 1026–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kulasakara H., Lee V., Brencic A., Liberati N., Urbach J., Miyata S., Lee D. G., Neely A. N., Hyodo M., Hayakawa Y., Ausubel F. M., Lory S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2839–2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Navarro M. V., De N., Bae N., Wang Q., Sondermann H. (2009) Structure 17, 1104–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guzzo C. R., Salinas R. K., Andrade M. O., Farah C. S. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 393, 848–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang B., Whitchurch C. B., Mattick J. S. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 7068–7076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rao F., Pasunooti S., Ng Y., Zhuo W., Lim L., Liu A. W., Liang Z. X. (2009) Anal. Biochem. 389, 138–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pasunooti S., Surya W., Tan S. N., Liang Z. X. (2010) J. Mol. Catal. B Enzyme 67, 98–103 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoofnagle A. N., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32, 1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao F., Qi Y., Chong H. S., Kotada M., Li B., Li J., Lescar J., Tang K., Liang Z. X. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 4722–4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang Z. X., Tsigos I., Lee T., Bouriotis V., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G., Klinman J. P. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14676–14683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang Z. X., Lee T., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G., Klinman J. P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9556–9561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weis D. D., Engen J. R., Kass I. J. (2006) J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1700–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Djordjevic S., Goudreau P. N., Xu Q., Stock A. M., West A. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1381–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinson V. L., Wu T., Stock A. M. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 4186–4194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ye S., Vakonakis I., Ioerger T. R., LiWang A. C., Sacchettini J. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20511–20518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guhaniyogi J., Wu T., Patel S. S., Stock A. M. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 1419–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boehm A., Kaiser M., Li H., Spangler C., Kasper C. A., Ackermann M., Kaever V., Sourjik V., Roth V., Jenal U. (2010) Cell 141, 107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fang X., Gomelsky M. (2010) Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1295–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paul K., Nieto V., Carlquist W. C., Blair D. F., Harshey R. M. (2010) Mol. Cell 38, 128–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ryjenkov D. A., Simm R., Römling U., Gomelsky M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30310–30314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.