Abstract

BST-2/tetherin is a host antiviral molecule that functions to potently inhibit the release of enveloped viruses from infected cells. In return, viruses have evolved antagonists to this activity. BST-2 traps budding virions by using two separate membrane-anchoring regions that simultaneously incorporate into the host and viral membranes. Here, we detailed the structural and biophysical properties of the full-length BST-2 ectodomain, which spans the two membrane anchors. The 1.6-Å crystal structure of the complete mouse BST-2 ectodomain reveals an ∼145-Å parallel dimer in an extended α-helix conformation that predominantly forms a coiled coil bridged by three intermolecular disulfides that are required for stability. Sequence analysis in the context of the structure revealed an evolutionarily conserved design that destabilizes the coiled coil, resulting in a labile superstructure, as evidenced by solution x-ray scattering displaying bent conformations spanning 150 and 180 Å for the mouse and human BST-2 ectodomains, respectively. Additionally, crystal packing analysis revealed possible curvature-sensing tetrameric structures that may aid in proper placement of BST-2 during the genesis of viral progeny. Overall, this extended coiled-coil structure with inherent plasticity is undoubtedly necessary to accommodate the dynamics of viral budding while ensuring separation of the anchors.

Keywords: Innate Immunity, Interferon, Viral Replication, X-ray Crystallography, X-ray Scattering, Host Antiviral Response

Introduction

Viruses must utilize host cell machinery to replicate and produce new virions. Efficient amplification, including virus release and infection of new cells, is obligatory for virus survival and disease pathogenesis. To subvert this process, host cells encode several interferon-inducible antiviral factors that constitute the first line of innate immune defense (1, 2). These antiviral factors interfere with various steps in the viral replication pathway to aid in clearance.

BST-2 (bone marrow stromal antigen 2; also known as tetherin, CD317, and HM1.24) is a recently discovered host antiviral factor that blocks viral replication by trapping enveloped viral progeny on the surface of infected cells, which leads to their internalization and degradation (3, 4). In response, several viruses have evolved countermeasures to nullify BST-2 and facilitate release (5). Most investigations that demonstrated BST-2-mediated restriction of virus release were conducted using either mutant viruses deficient in their BST-2-mitigating proteins or virus-like particles. For example, BST-2 antiviral activity was first demonstrated for HIV-1 deficient in the viral membrane protein Vpu (6, 7). Since then, studies using either virus-like particles or antagonist-deficient viruses have demonstrated BST-2-mediated restriction of several retroviruses (alpha-, beta-, delta-, lenti-, and spumaretroviruses) (8), arenaviruses (Lassa and Machupo) (9, 10), herpesviruses (Karposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) (11), filoviruses (Ebola and Marburg) (8, 9), and paramyxoviruses (Nipah) (10). However, a recent study using intact infectious viruses indicated that BST-2 does not restrict filoviruses (Ebola and Marburg), poxviruses (cowpox), or bunyaviruses (Rift Valley fever virus), suggesting these viruses either encode antagonists or utilize budding pathways that circumvent BST-2 activity. Interestingly, infectious arenaviruses (Lassa and Machupo) (10) are restricted by BST-2. Thus, BST-2 exhibits a broad, but not universal, spectrum of activity targeting enveloped virus release. Furthermore, this appears to be an evolutionarily conserved function, as the BST-2 homologs from humans, several species of primates (12–14), mice (10, 15), and rats (15, 16) have all been shown to restrict HIV-1 and several other enveloped viruses (10).

BST-2 is a type II transmembrane protein with a unique topology consisting of a short N-terminal cytoplasmic tail; a single transmembrane region (TMR);3 an ectodomain; and a second membrane anchor, a C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI). It has been found to localize within lipid rafts on the cell surface and trans-Golgi network membrane (17). Because the activity of BST-2 requires co-localization with budding virions, many viruses encode countermeasures to remove it from the cell surface. HIV-1 Vpu interacts with the TMR and directs surface removal of BST-2, although the exact mechanism remains unclear (18–23). Karposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K5 interacts with the cytoplasmic tail and mediates a ubiquitin-dependent down-regulation of BST-2 (11, 24). Interestingly, the envelope glycoproteins of HIV-2 (Env) (19, 25) and Ebola (GP) (26, 27) antagonize BST-2 directly through interaction with the ectodomain.

The bulk of the literature suggests that BST-2 restricts enveloped virus release by directly bridging the host and viral membranes through simultaneous inclusion using its two opposing membrane anchors (28, 29). Indeed, deletion of either the TMR or GPI renders BST-2 nonfunctional for HIV-1 restriction (7, 28). BST-2 is surface-expressed as a disulfide-linked homodimer (30). Disulfide cross-linking through at least one of the three conserved cysteines is necessary for antiviral function (28, 31). Recent structural studies of a human BST-2 ectodomain C-terminal fragment revealed an irregular coiled coil that exhibits conformational flexibility (32).

Here, we present the first high resolution crystal structure of the full-length mouse BST-2 ectodomain. The structure reveals an extended α-helix spanning nearly the entire ectodomain, predominantly forming a disulfide-linked coiled coil. Thermal denaturation dictates this structure to be unstable in the absence of the disulfides. This instability produces structural plasticity in solution as detected by small angle x-ray scattering. Our structural and biophysical analysis of mouse and human BST-2 ectodomains suggests an evolutionarily conserved design encoding an unstable coiled coil that requires intermolecular disulfides for stability. Such a design produces a conformationally labile dimer that can adapt during the dynamic events of viral assembly and budding while providing necessary separation for the membrane anchors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs and Recombinant Proteins

The ectodomains of mouse (amino acids 53–151) and human (amino acids 45–160) BST-2 were cloned into pET23b with artificial start methionines as tagless constructs. The mouse BST-2 (mBST-2) ectodomain was generated by PCR amplification from full-length cDNA. A human BST-2 (hBST-2) ectodomain construct was codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli generated by PCR-based gene synthesis (33). Both constructs were confirmed by sequencing and transformed into Rosetta 2(DE3) cells (Novagen) for protein expression.

Protein Expression and Purification

BST-2 ectodomains were expressed in E. coli as insoluble proteins, which were recovered from inclusion bodies, denatured in guanidine hydrochloride, and then refolded under oxidative conditions by rapid dilution. The resulting soluble proteins were purified by gel filtration followed by ion exchange chromatography. The proteins were well folded as assessed by circular dichroism.

Antibody Binding Assay for the Refolded mBST-2 Ectodomain

The refolded mBST-2 ectodomain was assessed for proper folding using anti-mBST-2 mAb 927, which was raised against cell surface-expressed mBST-2. Direct binding was assessed by biolayer interferometry using a ForteBio Octet platform. Briefly, streptavidin-coated biosensors from ForteBio were used to capture biotinylated mAb 927 onto the surface of the sensor. After reaching base line, sensors were moved to the association step containing 900, 450, 225, 112.5, 56.3, 28.1, 14.1, or 7.03 nm mBST-2 ectodomain for 300 s and then dissociated for 300 s. A buffer-only reference was subtracted from all curves. The running buffer consisted of 10 mm Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 3.4 mm EDTA, 1% BSA, 0.01% azide, 0.05% Tween, and 0.005% Triton X-100. Affinities were estimated from global kinetic analysis of the three lowest concentrations (KD = 1.8 nm). No binding to the refolded hBST-2 ectodomain at 900 nm was observed under the same conditions.

Cell-based Competitive Binding Assay

The refolded mBST-2 ectodomain was additionally assessed for proper folding using a competitive binding assay. The mouse T cell hybridoma 14-3-1 (high BST-2-expressing) and human 293T cells (non-BST-2-expressing) were plated at 1–2 × 105 cells/well in 96-well round-bottom plates. The refolded mBST-2 ectodomain diluted in FACS buffer (2% BCS in PBS) was added to wells. Immediately after adding mBST-2, anti-mBST-2 mAb 927 (rat IgG2b) diluted in Fc block (1:100) was added to the wells (final dilution of 1:200). Cells were incubated for 30 min on ice and then washed three times with FACS buffer. Allophycocyanin-conjugated streptavidin (1:400 in FACS buffer) was added to the wells for 20 min on ice. Cells were then washed three times with FACS buffer, resuspended, and analyzed on a FACSCalibur using propidium iodide to gate out dead cells. Samples were run in duplicate and repeated. Fig. 1B shows the mean fluorescence intensity of mAb 927 staining using different concentrations of the mBST-2 ectodomain.

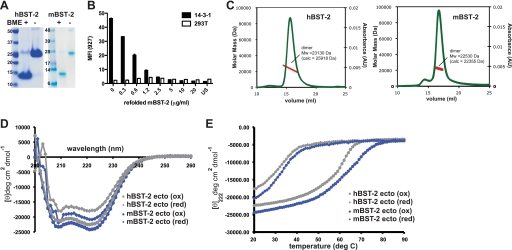

FIGURE 1.

Biochemical and biophysical properties of BST-2 ectodomains. A, refolded BST-2 ectodomains are disulfide-linked covalent dimers. SDS-PAGE of the hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains was performed with and without reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol (BME)). B, the refolded mBST-2 ectodomain competes with BST-2-expressing 14-3-1 cells for binding to anti-mBST-2 mAb 927. The bar graph shows the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of mAb 927 staining using increasing concentrations of mBST-2. HEK293T cells (which do not express BST-2) were used as a negative control. C, MALS of the mBST-2 (right panel) and hBST-2 (left panel) ectodomains. The molecular mass determined closely matched that of the covalent dimer in each case (for hBST-2, MALS and actual molecular masses = 23,130 and 25,918 Da, respectively; and for mBST-2, MALS and actual molecular masses = 22,530 and 22,355, Da, respectively). AU, absorbance units. D, CD spectra of the hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains (ecto) under native (oxidized (ox)) and reduced (red) conditions. Spectra are plotted as mean ellipticity per residue. deg, degrees. E, thermal denaturation by measurement of CD at 222 nm for the hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains under native and reduced conditions. Both showed a dramatic reduction in denaturation temperature when the disulfide bonds were broken. The calculated Tm values are as follows: for mBST-2, 68 °C (oxidized) and 32 °C (reduced); and for hBST-2, 61 °C (oxidized) and 31 °C (reduced).

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

Attempts to determine the crystal structure of the hBST-2 ectodomain were hindered by poorly diffracting crystals and endogenous proteolytic degradation of the protein that made optimization difficult. A single degradation product was always observed at ∼8 kDa. N-terminal sequencing and mass spectrometry of the degradation product revealed the cleavage site to be Phe-81.

Crystals of the mBST-2 ectodomain were obtained by mixing protein solution (at 10 mg/ml) with reservoir solution (100 mm phosphate/citrate (pH 4.6), 35% isopropyl alcohol, and 5% PEG 1000) at a 1:1 ratio. Crystals routinely formed over the course of 1 week. Crystals were cryoprotected in reservoir solution (with isopropyl alcohol reduced to 30%) supplemented with 25% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol and stream-frozen at 100 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected at Advanced Light Source beamline 4.2.2 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Crystals contained one dimer in the asymmetric unit with 42% solvent content. Data were processed using HKL-2000 (34). Data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic statistics for the mBST-2 ectodomain (amino acids 53–151)

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection statistics | |

| Space group | I212121 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = 33.7, b = 100.8, c = 110.4 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0007 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.60 (1.66-1.60) |

| Rsym (%) | 0.064 (0.368) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (100) |

| Redundancy | 6.6 (6.5) |

| I/σ | 28.0 (4.1) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.15-1.60 (1.66-1.60) |

| No. of reflections | 23,628 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.214/0.237 (0.222/0.276) |

| Protein/hydrogen/solvent atoms | 1457/1472/214 |

| Average B protein/solvent (Å2) | 30.4/40.4 |

| r.m.s.d. bond (Å)/angle | 0.003/0.564° |

| Luzzati error (Å) | 0.21 |

The phase problem was solved by molecular replacement in the program PHASER (35) by locating a single 40-residue polyalanine dimer fragment from the coiled-coil protein cortexillin I (Protein Data Bank code 1D7M) (36) followed by two copies of an ensemble consisting of 10 20-mer α-helices. The model was built by a combination of auto-rebuilding with PHENIX (37) using RESOLVE (38) and manual building with COOT (39). Refinement against data to 1.6 Å was carried out in PHENIX. Hydrogens were generated in the final stages of refinement and included as a riding model. The final model consisted of residues 57–151 (chain A) and residues 58–144 (chain B). All residues are within the most favored (98.3%) and additionally allowed (1.7%) regions of a Ramachandran plot. Molecular graphics figures were created using PyMOL. Structures were superposed using the “user defined match” option in CCP4MG Version 2.4.0 (40). Knobs-into-holes packing analysis with SOCKET (41) determined coiled-coil boundaries. Variations in coiled-coil structure were analyzed using TWISTER (42). Sequence conservation was calculated using ALSCRIPT (43), and GPI anchor positions were predicted using the BIG-PI predictor (44). The coordinates and experimental structure factors of the mBST-2 ectodomain have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 3NI0).

Circular Dichroism Studies

CD spectroscopy measurements were performed using a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. Thermal denaturation experiments were carried out in 20 mm phosphate (pH 7.0) and 100 mm NaCl. For reducing conditions, the buffer contained 1 mm DTT. Ellipticity was measured at 222 nm in 1 °C steps from 20 to 90 °C at a rate of 1 °C/min.

Small Angle X-ray Scattering

Solution x-ray scattering data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory) on beamline X-9. Scattering intensity data for both hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains were collected at 2, 5, and 10 mg/ml in buffer consisting of 20 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, and 5 mm EDTA. Scattering data for each concentration were collected in triplicate and averaged after normalization and buffer subtraction. All data analysis and calculations were performed using the ATSAS software suite (45). Data were processed in PRIMUS and regularized using GNOM. Calculated scattering plots from CRYSOL using the mBST-2 ectodomain crystal structure dimer as well as tetramers produced by crystal packing did not fit the observed scattering data well. Mixtures using these three models in OLIGMER did not fit the data well either; thus, ab initio modeling was employed. Models were created using GASBOR (46) with the final models a result of 10 independent predictions averaged in DAMAVER.

Multi-angle Light Scattering

Purified BST-2 ectodomains were subjected to size exclusion chromatography/multi-angle light scattering (MALS) using a Waters HPLC system connected to a DAWN HELEOS II 18-angle light scattering detector (Wyatt Technology Corp.) combined with an Optilab rEX differential refractometer. Protein samples (300 μl) were loaded onto a Superdex S-200 10/300 GL gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) at a concentration of ∼2.0 mg/ml and run at 0.5 ml/min in buffer consisting of 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.01% NaN3. Data were recorded and processed using ASTRA software (Wyatt Technology Corp.).

RESULTS

Biochemical and Functional Characterization of Refolded BST-2 Ectodomains

Recombinant mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains were produced by refolding from denatured inclusion bodies; thus, the proteins were characterized to verify that they were similar to the natively folded surface-expressed forms. Both hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains displayed a shift to dimer molecular masses on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions (Fig. 1A), indicating that intermolecular disulfide bonds had formed, as observed in the native surface-expressed protein (30). Additionally, the refolded mBST-2 ectodomain was assayed for binding to mAb raised against cell surface-expressed mBST-2 (47). The mBST-2 ectodomain bound with high affinity (KD = 1.8 nm) (data not shown) and was able to compete for binding with BST-2-expressing cells (Fig. 1B). No antibody binding to the hBST-2 ectodomain was observed. Thus, the refolded BST-2 ectodomains displayed features consistent with properly surface-expressed proteins. Defined higher order oligomers were not observed by gel filtration chromatography coupled with MALS, as both mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains eluted predominantly as a single species in solution with determined masses corresponding to the respective covalent dimers (Fig. 1C).

BST-2 Ectodomains Are Thermally Unstable in the Absence of Intermolecular Disulfide Bonds

Previous biophysical studies of the hBST-2 ectodomain indicated that the coiled-coil dimer is highly unstable upon reduction of the intermolecular disulfide bonds (32). We sought to evaluate whether or not this structural instability is a conserved feature of the BST-2 ectodomain. The hBST-2 and mBST-2 ectodomains display a sequence identity that is near the average for this molecule when compared across species (50% identical) (see Fig. 3, A and H). Both mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains are highly α-helical in solution as assessed by circular dichroism, and helical content was slightly reduced by breaking the intermolecular disulfide bonds via the addition of reducing agent (Fig. 1D). Thermostability was greatly affected, however, as the denaturing temperatures dropped dramatically in the presence of reducing agent (for the mBST-2 ectodomain, Tm(ox) = 68 °C and Tm(red) = 32 °C; and for the hBST-2-ectodomain, Tm(ox) = 61 °C and Tm(red) = 31 °C) (Fig. 1E). Thus, the intermolecular disulfide bonds are required to provide stability. This suggests that the coiled-coil instability encoded in the BST-2 ectodomain may be an evolutionarily conserved feature that is required for function.

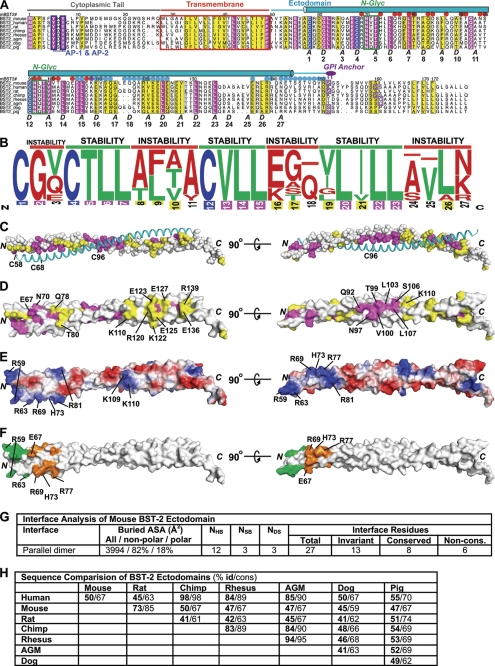

FIGURE 3.

Sequence and surface analysis of the BST-2 ectodomain. A, alignment of BST-2 sequences. Invariant residues (except cysteines) are magenta, invariant cysteines are blue, and residues highlighted yellow denote a conservation index of 6 or higher as determined by ALSCRIPT (43). The secondary structure of the mBST-2 ectodomain is shown above the alignment. Numbering is from mBST-2 (mBST-2#). Green boxes denote the N-linked glycosylation (N-Glyc) sites, and blue boxes highlight trafficking motifs utilized by AP-1 and AP-2. GPI anchor positions predicted by the BIG-PI Predictor (44) are shown as purple boxes. The letters A and D indicate coiled-coil core heptad repeat positions as determined by TWISTER. Dots above the sequence indicate residues located at the interface of the two possible dimer-of-dimers assemblies in the crystal: assembly 1 (red dots), assembly 2 (blue dots), and both assemblies (violet dots). Suffixes in sequence names indicate species as follows: mouse, Mus musculus; human, Homo sapiens; rat, Rattus norvegicus; chimp, Pan troglodytes; rhesus, Macaca mulatta; African green monkey (agm), Chlorocebus tantalus; dog, Canis lupus familiaris; and pig, Sus scrofa. B, sequence logo frequency plot of coiled-coil interface residues. Blue, cysteine; green, favorable coiled-coil interface residues (ILVT); red, unfavorable coiled-coil interface residues (all others). Numbering of interface position is color-coded according to sequence conservation as shown above. C, sequence conservation and invariance at the covalent dimer interface. One chain of the dimer is shown as space-filled and colored according to the sequence alignment shown in A, whereas the other is shown as a cyan coil. D, sequence conservation mapped onto the solvent-accessible surface of the mBST-2 ectodomain. E, charge-smoothened electrostatic surface as calculated by PyMOL. Blue denotes positively charged surfaces, whereas red denotes negatively charged surfaces (gradient, +70 to −70). F, surface mapping of cluster mutations previously demonstrated (32) that do not (green) and do (orange) prevent hBST-2 from restricting HIV-1 budding. These residues (mouse/human) are Arg-59/Arg-54, Asp-60/Asp-55, and Arg-63/Arg-58 (green) and Glu-67/Glu-62, Arg-69/Arg-64, Asn-70/Asn-65, His-73/His-68, Gln-76/Gln-71, Arg-77/Gln-72, and Gln-78/Glu-73 (orange). G, interface analysis of the mBST-2 ectodomain covalent dimer. ASA, accessible surface area; NHB, number of hydrogen bonds; NSB, number of salt bridges; NDS, number of disulfide bonds; Non-cons., non-conserved. H, table of direct sequence comparisons between BST-2 ectodomains from various species.

Crystal Structure of the Full-length mBST-2 Ectodomain

The crystal structure of the mBST-2 ectodomain was determined to a very high resolution (1.6 Å). The final model was very high quality (Table 1) and consisted of one homodimer in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 2A). Electron density was visible for nearly the entire ectodomain (Fig. 2B), with chain A missing only four N-terminal residues and chain B missing five N-terminal and seven C-terminal residues. The structure reveals an elongated parallel α-helical dimer bridged by three intermolecular disulfide bonds. The ectodomain is α-helical for nearly the entire length with the exception of the C-terminal seven-residue GPI-connecting loop and presumably the initial disordered five-residue TMR-connecting loop. The extended conformation has the approximate dimensions of 25 Å (width) × 145 Å (length).

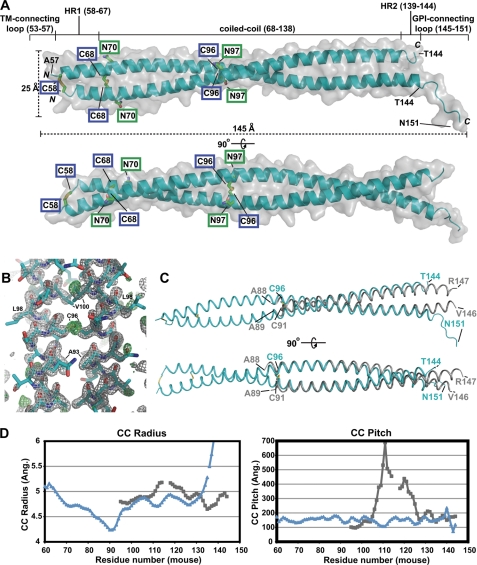

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of the mBST-2 ectodomain (amino acids 53–151). A, the 1.6-Å crystal structure of the mBST-2 ectodomain reveals a parallel α-helical covalent dimer bridged by three intermolecular disulfide bonds. The approximate dimensions shown were calculated in MOLEMAN2. Chain A includes residues 57–151, whereas chain B includes residues 58–144. Cysteine residues involved in intermolecular disulfides (blue boxes) are shown as sticks, as are the two N-linked glycosylation sites (green boxes). TM, transmembrane region. B, electron density after rigid body refinement of the molecular replacement solution. The model shown is the final coordinates. Grey mesh represents a 2Fo − Fc map contoured at 2.0 σ, whereas green mesh represents Fo − Fc contoured at 3.0 σ. Note the readily identifiable disulfide electron density. C, superposition of the mBST-2 ectodomain (cyan) and an hBST-2 ectodomain fragment (grey; Protein Data Bank code 2X7A) (32). Structures were superposed using the “user defined match” option in CCP4MG Version 2.4.0. The Cα r.m.s.d. between superposed dimers is 2.35 Å (r.m.s.d. for individual chains are 1.15 and 1.10 Å, respectively). D, comparison of coiled-coil (CC) parameters for the mBST-2 (blue) and hBST-2 (grey) ectodomains. Values were measured using TWISTER (42). Ang., angstrom.

A majority of the ectodomain (amino acids 68–138) conforms to coiled-coil packing. Deviations from coiled-coil packing occur in short α-helical regions on either side of the central coiled coil (HR1 and HR2). Near the N terminus, the α-helices are slightly splayed due to the presence of two destabilizing residues that occur at heptad interface positions, an α-helix-destabilizing glycine (Gly-61) followed by a hydrophilic residue (Gln-65) (see Fig. 3, A and B). The C-terminal end of the coiled coil is disrupted by Lys-142, which lies at a heptad interface position and splays apart the coiled coil. In contrast to the previously determined structure of a C-terminal fragment of the hBST-2 ectodomain (Fig. 2C) (32), the mBST-2 ectodomain is more tightly packed as gauged by the coiled-coil radius and pitch (Fig. 2D) and displays no stutters (discontinuities) in the coiled-coil heptad repeat. Overall, the two structures are quite divergent (root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 2.35 Å for C-α overlay of the dimers and r.m.s.d. of 1.15 and 0.94 Å for individual chains A and B, respectively). This is due mostly to four nearly consecutive conservative differences at heptad positions in a short section from Lys-110 to Ile-121. The comparative positions between mBST-2 and hBST-2 are Lys-110/Glu-105, Ala-114/Gly-109, Ile-121/Val-113, and Val-128/Ile-120. The largest variation in this stretch is the Glu-105 and Gly-109 combination in hBST-2, which causes a stutter (discontinuity) in the heptad repeat at Gly-109 (32). In comparison, the equivalent positions of mBST-2 actually pack tighter as evidenced by the decrease in coiled-coil radius in this section (Fig. 2D). The other major structural divergence occurs near the C-terminal end, where the mBST-2 ectodomain starts to splay apart due to Lys-142, whereas this section of hBST-2 becomes more tightly packed.

The interface residues in the region N-terminal to Cys-96 are highly conserved when comparing mouse and human. There are four differences in this region: Gln-65/Val-60, Thr-82/Ala-77, Leu-86/Phe-81, and Ala-89/Val-84. Interestingly, the occurrence of Phe-81 (in the hBST-2 ectodomain) at the coiled-coil interface may explain the proteolytic susceptibly at this position compared with the mBST-2 ectodomain, as the large Phe side chain would upset regular coiled-coil packing. In summary, the mBST-2 coiled coil displays tighter packing, no coiled-coil discontinuities, and reduced endogenous proteolytic susceptibility compared with the hBST-2 ectodomain due largely to a handful of conservative substitutions at the dimer interface. However, despite these structural observations, the mBST-2 ectodomain is highly unstable in the absence of the intermolecular disulfide bonds.

Design of an Unstable Coiled Coil Revealed by Structure-based Sequence Analysis

Elucidation of the full structure of the coiled-coil ectodomain allowed analysis of the heptad interface across all BST-2 sequences (Fig. 3, A and B). Much of the sequence conservation and invariance across species are found at the coiled-coil interface (Fig. 3, C and G). Coiled coils possess characteristic heptad sequence repeats in which the A and D positions are normally occupied by small hydrophobic residues (e.g. valine, isoleucine, and leucine). This creates a hydrophobic seam that zippers α-helices together with A and D positions interlocked in what is termed “knobs-into-holes” packing. Introduction of hydrophobic side chains that are too large (e.g. phenylalanine) or too small (alanine) or hydrophilic residues is not favored and can disrupt the interface. Sequence analysis of the BST-2 coiled-coil interface across species revealed a unique design composed of short stretches of invariant stabilizing residues alternating with stretches of destabilizing residues (Fig. 3B). Coiled-coil formation is a cooperative phenomenon, requiring a critical fragment length for stability. Thus, it appears that BST-2 has been evolutionarily designed with encoded instability and that this designed instability is required for optimal antiviral function.

Surface Analysis of the BST-2 Ectodomain

Surface mapping of sequence conservation can highlight functional hot spots. So far, the antiviral activity is the only function of BST-2 that is conserved across all species studied. Thus, we would expect clusters of sequence-conserved surface residues to highlight regions important for the antiviral function. Two major patches of surface conservation occur in the areas near the two N-linked glycosylation sites, Asn-70 and Asn-97 (Fig. 3B). A third major patch occurs at the C-terminal half in a region from Arg-120 to Val-128. It is possible that this could be a binding site for a yet unidentified accessory protein. Interestingly, a cluster of surface mutations near the N terminus that were shown to disrupt BST-2 antiviral function against HIV-1 are partially coincident with the first patch of sequence conservation (Fig. 3F) (32). The electrostatic surface of mBST-2 shows some features, most notably a large patch of basic residues at the N terminus (Fig. 3E).

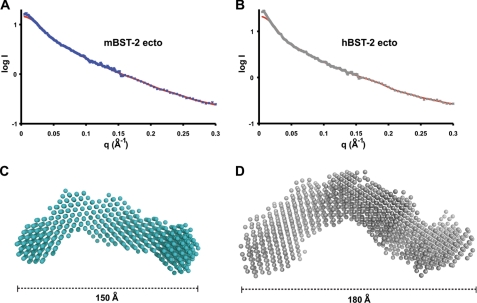

BST-2 Ectodomains Are Conformationally Labile in Solution

The solution structures of the mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains were evaluated by small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS). Guinier analysis revealed radii of gyration of 46.2 Å for the mBST-2 ectodomain and 51.2 Å for the hBST-2 ectodomain (supplemental Fig. S1). Calculation of the predicted scattering pattern using the mBST-2 ectodomain dimer did not fit the experimental data well, so ab initio modeling was employed. Maximal protein dimensions (Dmax) calculated from the distance distribution function p(r) were 150 Å for the mBST-2 ectodomain and 180 Å for the hBST-2 ectodomain. The ab initio models fit experimental data well with discrepancies (χ) of 1.7 and 2.6 for the mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Individual predictions were all irregular twisted rods, which averaged together to produce overall models of elongated bent rods for both ectodomains (Fig. 4, C and D). The distribution of dimensions for the mBST-2 ectodomain is 150 × 60 × 45 Å, whereas that for the hBST-2 ectodomain is 180 × 85 × 65 Å. The predicted structure for the hBST-2 ectodomain showed a much more diffuse distribution than that for the mBST-2 ectodomain, indicating a higher degree of conformational lability. Further analysis of scattering data revealed features at very low angles indicative of oligomerization (45). In summary, SAXS analysis indicated that the BST-2 ectodomain is conformationally flexible in solution, that the hBST-2 ectodomain is more labile than the mBST-2 ectodomain, and that both appear to form higher order associations in solution.

FIGURE 4.

Solution SAXS of BST-2 ectodomains. A and B, experimental scattering for the mBST-2 ectodomain (ecto) at 5 mg/ml (blue ×) and the hBST-2 ectodomain at 5 mg/ml (grey ×), respectively, along with calculated scattering (red lines) from ab initio models with lowest χ values. Experimental scattering is the average of three experiments with subtraction of buffer scattering. C and D, ab initio models of mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains, respectively, indicate bent flexible structures in solution. Models are the average of 10 independent GASBOR predictions averaged in DAMAVER.

DISCUSSION

The literature to date indicates that BST-2 restricts enveloped virus release through simultaneous inclusion in both host and viral membranes (28, 29). The BST-2 ectodomain performs the crucial role of linking the two membrane-anchoring regions (TMR and GPI anchor). Although an artificial BST-2 mimic in which much of the native ectodomain is replaced by a generic coiled coil from dystrophia myotonica protein kinase is still able to inhibit virus release, activity against HIV-1 is ∼10-fold lower compared with native BST-2 (28), implying that the unique features of the BST-2 ectodomain outlined in this study have optimized the protein for antiviral function. Here, we have shown for the first time that the entire BST-2 ectodomain can form an extended α-helical confirmation, much of which is a coiled coil that is similar in appearance to a two-stranded rope. This extended structure allows for maximal separation of the membrane anchors to preclude inclusion of both into a budding virion, which would thwart successful virus capture. In addition, the length of the BST-2 ectodomain (150 Å for mouse and 180 Å for human) is longer than that of many virus spikes (e.g. ∼120 Å for HIV-1 (48)), which would also be required to bridge the separating membranes.

The BST-2 ectodomain displays conserved structural and physical properties that are crucial to function. The mBST-2 ectodomain is a parallel homodimer bridged by three disulfide bonds. The functional importance of the intermolecular disulfides has been demonstrated, as mutation of single cysteines has little effect on virus-tethering function, whereas mutation of all three destroys antiviral function against HIV-1 (28, 31). Here, we have demonstrated that the coiled-coil ectodomain is unstable in the absence of the intermolecular disulfides, as both mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains displayed greatly decreased thermostability under reducing conditions. This appears to be a evolutionarily conserved feature of the ectodomain, as sequence analysis suggested a design composed of alternating stretches of residues that stabilize and destabilize the coiled-coil interface. The importance of proper formation of the last two intermolecular disulfides is highlighted by the invariant stretch of coiled coil-stabilizing residues immediately preceding them. Interestingly, the first disulfide is preceded by an invariant α-helix-destabilizing glycine followed mostly by a hydrophilic residue. These residues disrupt regular coiled-coil packing, yet the disulfide is able to form. It should be noted that clusters of mutations designed to completely disrupt the coiled-coil interface ablate the antiviral function against HIV-1 (32). Thus, a fine balance between instability and functional design has been achieved.

These encoded instabilities also likely produce the conformational lability observed for the mBST-2 and hBST-2 ectodomains in solution. Although both are predicted to be bent, non-rigid structures in solution, hBST-2 appears to be more conformationally diffuse, likely due to the introduction of more coiled coil-destabilizing side chains and discontinuities compared with mBST-2. In terms of antiviral function, the assembly and budding of virions are structurally dynamic processes, and the conformational plasticity of the BST-2 ectodomain would be advantageous for viral trapping. Similar coiled coil-destabilizing designs are also observed in streptococcus M1 protein (49), tropomyosin (50), and myosin (51). In these proteins, the instabilities cause helical unwinding, which, for myosin, is necessary for function (51, 52). BST-2 is unique in this regard, as the intermolecular disulfides prevent major separation of the helices, so the end result of the coiled-coil instabilities is a dynamic structure. It is also possible that BST-2 may have a yet unidentified conserved cellular function involving a cell-surface binding partner as suggested by the presence of large surface patches of sequence conservation. Indeed, hBST-2 has been shown to bind the plasmacytoid dendritic cell receptor ILT7 and signal to inhibit type I interferon secretion (53). However, this function may not be conserved between humans and mice, as there is no known murine ortholog for ILT7.

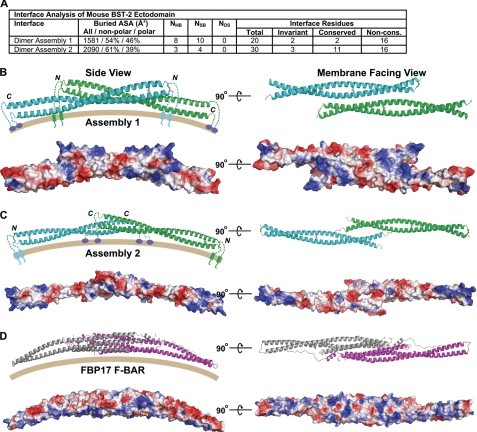

Analysis of crystal contacts can highlight possible oligomers that may have functional relevance. Such analysis for the mBST-2 ectodomain revealed two possible dimer-of-dimers assemblies that bury significant amounts of surface area (Fig. 5, A–C). These associations may be weak, as they were not observed under the flow conditions of size exclusion chromatography. However, extensive contacts are observed in the crystal, and features of SAXS in solution suggest that some self-association may occur. Interestingly, both bear a slight similarity to the BAR domain family (Fig. 5D). BAR domains are α-helical modules that dimerize and form crescent-shaped structures that bind to and stabilize curved membranes during membrane trafficking events (54). Of the two assemblies, assembly 2 is more likely to occur, as the interface is larger, is composed of more non-polar residues, and is composed of residues near the C terminus, away from the N-linked glycosylation sites that would prevent dimerization. In addition, this assembly would place the GPI anchors of adjacent dimers near each other, which is also consistent with the propensity of GPI anchors to localize to lipid rafts. This assembly also contains patches of basic residues on the predicted membrane-facing side, consistent with a possible membrane-binding function. Because viral assembly and release from the cell surface involve membrane deformation and bending, it is reasonable to hypothesize that these curved assemblies may have some functional purpose in the antiviral function of BST-2.

FIGURE 5.

Possible assemblies created by crystal packing. A, interface surface analysis for the two major assemblies created by crystal packing. Symmetry operations creating the assemblies were as follows: assembly 1, −x + 5/2, y, −z + 1; and assembly 2, −x + 1/2, y, −z. ASA, accessible surface area; NHB, number of hydrogen bonds; NSB, number of salt bridges; NDS, number of disulfide bonds; Non-cons., non-conserved. B and C, assemblies 1 and 2, respectively, viewed from the perspective of a side view on an outwardly curving membrane (left) and the membrane-facing surface (right). Below the ribbon diagrams are the respective electrostatic surfaces as calculated by PyMOL. For B, the C-terminal GPI-connecting loop has been removed from chain A. D, comparison with the FBP17 F-BAR domain (Protein Data Bank code 2EFL), a member of the BAR domain superfamily that binds to curved membranes.

High local concentrations would support the formation of such oligomers, and in support of this, recent immunogold cryo-EM studies demonstrate that BST-2 forms clusters at HIV-1 budding sites (55, 56). Viral assembly is a dynamic process involving sorting and clustering of surface glycoproteins, membrane bending, and finally membrane fission. Thus, it is reasonable that such BAR-like curved shapes could have functional significance. For example, they could aid in targeting BST-2 to cluster around the neck of a budding virus for correct positioning to avoid full inclusion in the progeny virion, or higher order structures could form proteinaceous collars around the neck, such as observed for the CIP4 F-BAR module (57). Such collars could stall or inhibit viral budding.

On the basis of our structural analysis and the current literature, we propose the following model of BST-2-mediated restriction of virus release. BST-2 must first locate to regions of viral assembly. Most enveloped viruses are believed to begin their assembly processes in lipid rafts. Given that GPI anchors prefer these cholesterol-rich microdomains, this is the most likely mechanism of co-localization. Another possible mechanism could involve sorting via an intracellular partner, such as RICH2 (58). Given the current information, we prefer the former, with an orientation such as that observed in assembly 2 (Fig. 5C) being likely. This orientation allows clustering of the GPI anchors of a pair of BST-2 homodimers near a lipid raft viral assembly site (maximizing for probability of inclusion) and keeps the N-terminal TMRs at a safe distance to prevent their inclusion in the viral membrane. As the viral proteins assemble and the membrane begins to curve outward, the structural plasticity of the BST-2 ectodomain would come into play, as it would be able to change shape as needed while staying firmly anchored in the viral membrane. At this point, the curved structures of BST-2 assemblies could be utilized, allowing BST-2 to cluster and collar around the neck to keep it near the host membrane and prevent full inclusion in the viral membrane. Next, the virus buds off the surface with a membrane anchor of the BST-2 homodimer planted in the viral membrane. Thin-section EM images support a large distance between virions and the plasma membrane (7, 28), and immunogold cryo-EM studies suggest a rod-like structure for BST-2 connecting the virus to the plasma membrane (56). This evidence points to a model with opposite ends of the homodimer embedded in the host and viral membranes, respectively. Taking into account steric considerations, we prefer an orientation with the GPI anchor stationed in the viral membrane, as this would place the narrower end of the molecule in the viral membrane with the larger N-terminal end of the dimer (containing four bulky glycosylation appendages) juxtaposed. Having the narrower end of the molecule in the viral membrane would allow for better avoidance of viral coat proteins during assembly and budding.

The physical features of the BST-2 ectodomain appear to be optimally developed for function as a virus tether. First, the extended structure provides separation of the membrane anchors so as to avoid full inclusion in the viral membrane. This structure is also longer than many enveloped virus spikes, so it can span the distance between the host and viral membranes. The conformational plasticity of the dimeric ectodomain allows it keep up with dynamic membrane deformation and protein assembly events that occur during viral genesis. Finally, curved assemblies of BST-2 may bind curved membrane to correctly position BST-2 near the neck of the budding virus.

Although much mechanistic detail of BST-2 antiviral function has been elucidated in a short time, many questions remain. BST-2 appears to be effective against a number of enveloped viruses (in the absence of known antagonists); however, the full spectrum of BST-2 antiviral capability is unknown. Additionally, the contribution of intracellular binding interactions to BST-2 function has not been investigated. Also, in a broader context, the normal cellular function of BST-2 is largely unknown. Most importantly, the detailed mechanisms of viral antagonism of BST-2 are poorly understood. A full understanding of this host-pathogen relationship could lead to the development of broad-spectrum antiviral therapies against enveloped viruses that exploit BST-2 activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jay Nix for expert assistance with data collection at Advanced Light Source, Chris Nelson for assistance with MALS, William McCoy for assistance with biosensor experiments, Joe Batchelor for expert assistance analyzing SAXS data, and Robert Blankenship for use of a JASCO J-815 CD instrument.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3NI0) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- TMR

- transmembrane region

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- mBST-2

- mouse BST-2

- hBST-2

- human BST-2

- MALS

- multi-angle light scattering

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolf D., Goff S. P. (2008) Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 143–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sadler A. J., Williams B. R. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sauter D., Specht A., Kirchhoff F. (2010) Cell 141, 392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evans D. T., Serra-Moreno R., Singh R. K., Guatelli J. C. (2010) Trends Microbiol. 18, 388–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Douglas J. L., Gustin J. K., Viswanathan K., Mansouri M., Moses A. V., Früh K. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Damme N., Goff D., Katsura C., Jorgenson R. L., Mitchell R., Johnson M. C., Stephens E. B., Guatelli J. (2008) Cell Host Microbe 3, 245–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neil S. J., Zang T., Bieniasz P. D. (2008) Nature 451, 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jouvenet N., Neil S. J., Zhadina M., Zang T., Kratovac Z., Lee Y., McNatt M., Hatziioannou T., Bieniasz P. D. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 1837–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sakuma T., Noda T., Urata S., Kawaoka Y., Yasuda J. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 2382–2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radoshitzky S. R., Dong L., Chi X., Clester J. C., Retterer C., Spurgers K., Kuhn J. H., Sandwick S., Ruthel G., Kota K., Boltz D., Warren T., Kranzusch P. J., Whelan S. P., Bavari S. (2010) J. Virol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansouri M., Viswanathan K., Douglas J. L., Hines J., Gustin J., Moses A. V., Früh K. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 9672–9681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McNatt M. W., Zang T., Hatziioannou T., Bartlett M., Fofana I. B., Johnson W. E., Neil S. J., Bieniasz P. D. (2009) PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim E. S., Emerman M. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 11673–11681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia B., Serra-Moreno R., Neidermyer W., Rahmberg A., Mackey J., Fofana I. B., Johnson W. E., Westmoreland S., Evans D. T. (2009) PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goffinet C., Allespach I., Homann S., Tervo H. M., Habermann A., Rupp D., Oberbremer L., Kern C., Tibroni N., Welsch S., Krijnse-Locker J., Banting G., Kräusslich H. G., Fackler O. T., Keppler O. T. (2009) Cell Host Microbe 5, 285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goffinet C., Schmidt S., Kern C., Oberbremer L., Keppler O. T. (2010) J. Virol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kupzig S., Korolchuk V., Rollason R., Sugden A., Wilde A., Banting G. (2003) Traffic 4, 694–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dubé M., Roy B. B., Guiot-Guillain P., Binette J., Mercier J., Chiasson A., Cohen E. A. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hauser H., Lopez L. A., Yang S. J., Oldenburg J. E., Exline C. M., Guatelli J. C., Cannon P. M. (2010) Retrovirology 7, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iwabu Y., Fujita H., Kinomoto M., Kaneko K., Ishizaka Y., Tanaka Y., Sata T., Tokunaga K. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35060–35072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwabu Y., Fujita H., Tanaka Y., Sata T., Tokunaga K. (2010) Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 366–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitchell R. S., Katsura C., Skasko M. A., Fitzpatrick K., Lau D., Ruiz A., Stephens E. B., Margottin-Goguet F., Benarous R., Guatelli J. C. (2009) PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rong L., Zhang J., Lu J., Pan Q., Lorgeoux R. P., Aloysius C., Guo F., Liu S. L., Wainberg M. A., Liang C. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 7536–7546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pardieu C., Vigan R., Wilson S. J., Calvi A., Zang T., Bieniasz P., Kellam P., Towers G. J., Neil S. J. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le Tortorec A., Neil S. J. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 11966–11978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaletsky R. L., Francica J. R., Agrawal-Gamse C., Bates P. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2886–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lopez L. A., Yang S. J., Hauser H., Exline C. M., Haworth K. G., Oldenburg J., Cannon P. M. (2010) J. Virol. 84, 7243–7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perez-Caballero D., Zang T., Ebrahimi A., McNatt M. W., Gregory D. A., Johnson M. C., Bieniasz P. D. (2009) Cell 139, 499–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fitzpatrick K., Skasko M., Deerinck T. J., Crum J., Ellisman M. H., Guatelli J. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ohtomo T., Sugamata Y., Ozaki Y., Ono K., Yoshimura Y., Kawai S., Koishihara Y., Ozaki S., Kosaka M., Hirano T., Tsuchiya M. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258, 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrew A. J., Miyagi E., Kao S., Strebel K. (2009) Retrovirology 6, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hinz A., Miguet N., Natrajan G., Usami Y., Yamanaka H., Renesto P., Hartlieb B., McCarthy A. A., Simorre J. P., Göttlinger H., Weissenhorn W. (2010) Cell Host Microbe 7, 314–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoover D. M., Lubkowski J. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burkhard P., Kammerer R. A., Steinmetz M. O., Bourenkov G. P., Aebi U. (2000) Structure 8, 223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Potterton L., McNicholas S., Krissinel E., Gruber J., Cowtan K., Emsley P., Murshudov G. N., Cohen S., Perrakis A., Noble M. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2288–2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walshaw J., Woolfson D. N. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1427–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strelkov S. V., Burkhard P. (2002) J. Struct. Biol. 137, 54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barton G. J. (1993) Protein Eng. 6, 37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eisenhaber B., Bork P., Eisenhaber F. (2001) Protein Eng. 14, 17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mertens H. D., Svergun D. I. (2010) J. Struct. Biol. 172, 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Svergun D. I., Petoukhov M. V., Koch M. H. (2001) Biophys. J. 80, 2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blasius A. L., Giurisato E., Cella M., Schreiber R. D., Shaw A. S., Colonna M. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 3260–3265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhu P., Winkler H., Chertova E., Taylor K. A., Roux K. H. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McNamara C., Zinkernagel A. S., Macheboeuf P., Cunningham M. W., Nizet V., Ghosh P. (2008) Science 319, 1405–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brown J. H., Kim K. H., Jun G., Greenfield N. J., Dominguez R., Volkmann N., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E., Cohen C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8496–8501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blankenfeldt W., Thomä N. H., Wray J. S., Gautel M., Schlichting I. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17713–17717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li Y., Brown J. H., Reshetnikova L., Blazsek A., Farkas L., Nyitray L., Cohen C. (2003) Nature 424, 341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cao W., Bover L., Cho M., Wen X., Hanabuchi S., Bao M., Rosen D. B., Wang Y. H., Shaw J. L., Du Q., Li C., Arai N., Yao Z., Lanier L. L., Liu Y. J. (2009) J. Exp. Med. 206, 1603–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frost A., Unger V. M., De Camilli P. (2009) Cell 137, 191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Habermann A., Krijnse-Locker J., Oberwinkler H., Eckhardt M., Homann S., Andrew A., Strebel K., Kräusslich H. G. (2010) J. Virol. 84, 4646–4658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hammonds J., Wang J. J., Yi H., Spearman P. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frost A., Perera R., Roux A., Spasov K., Destaing O., Egelman E. H., De Camilli P., Unger V. M. (2008) Cell 132, 807–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rollason R., Korolchuk V., Hamilton C., Jepson M., Banting G. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 184, 721–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.