Abstract

Objective

An extensive literature uses reconstructed historical smoking rates by birth-cohort to inform anti-smoking policies. This paper examines whether and how these rates change when one adjusts for differential mortality of smokers and non-smokers.

Methods

Using retrospectively reported data from the US (Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1986, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005), the UK (British Household Panel Survey, 1999, 2002), and Russia (Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Study, 2000), we generate life-course smoking prevalence rates by age-cohort. With cause-specific death rates from secondary sources and an improved method, we correct for differential mortality, and we test whether adjusted and unadjusted rates statistically differ. With US data (National Health Interview Survey, 1967–2004), we also compare contemporaneously measured smoking prevalence rates with the equivalent rates from retrospective data.

Results

We find that differential mortality matters only for men. For Russian men over age 70 and US and UK men over age 80 unadjusted smoking prevalence understates the true prevalence. Results using retrospective and contemporaneous data are similar.

Conclusions

Differential mortality bias affects our understanding of smoking habits of old cohorts and, therefore, of inter-generational patterns of smoking. Unless one focuses on the young, policy recommendations based on unadjusted smoking rates may be misleading.

1. Introduction

A plethora of studies examine smoking trends by birth cohort with data from a wide range of countries (Ahacic et al., 2008; Anderson and Burns, 2000; Birkett, 1997; Brenner, 1993; Burns et al., 1998; Escobedo and Peddicord, 1996; Federico et al., 2007; Fernandez et al., 2003; Harris, 1983; Hill, 1998; Kemm, 2001; Laaksonen et al., 1999; La Vecchia et al., 1986; Marugame et al., 2006; Menezes et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Perlman et al., 2007; Ronneberg et al., 1994; Warner, 1989). These studies use generational patterns of smoking prevalence to assess the spread of smoking habits, the need for government intervention, or the effectiveness of existing tobacco control policies. Some also use the smoking patterns to inform policy improvements, such as focusing anti-smoking campaigns on specific sub-populations (by age, sex, or education level) and/or on specific smoking decisions (e.g. discouraging initiation or encouraging cessation).

To measure smoking behavior, some researchers combine retrospective and prospective smoking information (Ronneberg et al., 1994; Kemm, 2001). Others use data from repeated cross-sectional surveys to construct a pseudo panel that tracks smoking behavior contemporaneously (Ahacic et al., 2008; Hill, 1998; Laaksonen et al., 1999; Park et al., 2009). Most researchers measure smoking behavior with retrospectively reported data (Anderson and Burns, 2000; Birkett, 1997; Brenner, 1993; Burns et al., 1998; Escobedo and Peddicord, 1996; Federico et al., 2007; Fernandez et al., 2003; Harris, 1983; La Vecchia et al., 1986; Marugame et al., 2006; Menezes et al., 2009; Perlman et al., 2007; Warner, 1989). Virtually all acknowledge that estimates of historical smoking prevalence are potentially biased because smokers die sooner than non smokers. Due to this differential mortality, in any given sample of people who survive to answer a survey, one may underestimate smoking prevalence rates, especially for older cohorts. Consequently, resulting policy recommendations may be unreliable.

Harris (1983) was the first to draw attention to this issue, presenting evidence of bias with US data. However, because mortality data were scarce at the time, he used time-invariant correction factors derived from an unrepresentative population (US veterans). Further, he did not formally test whether his bias estimates were statistically significant. The substantial literature that follows generally acknowledges but only sometimes corrects for differential mortality. Even when researchers make the correction, they typically apply Harris’s method (Brenner, 1993; Fernandez et al., 2003; La Vecchia et al., 1986; Marugame et al., 2006; Warner, 1989) and, therefore, suffer many of the same shortcomings.

Using a more refined method and detailed mortality data, we aim to accurately measure the degree to which differential mortality of smokers and non-smokers biases estimates of historical smoking prevalence. We also examine how the bias differs across age-cohorts, genders, countries (Russia, UK, US), and types of data (retrospective and cross-sectional).

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We compute life-course smoking prevalence using retrospective collected data from the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID, 1986, 1999, 2001, 2003, and 2005); the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS, 1999, 2002); and the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Study (RLMS 2000). All surveys collect information on current and past smoking habits. Detailed descriptions of these surveys are widely-available.

To correct for differential mortality we use a rich set of age and gender-specific data on mortality and population. We draw cause-specific death and population data for the US and the UK from the World Health Organization mortality database. These data start in 1950 and 1953, respectively. For the US, we add cause-specific mortality data by age and gender-category for 1933–1949 from US Bureau of the Census reports. For the UK, earlier cause-specific mortality data are not available; our calculations for the years before 1953 use overall mortality data from the Human Mortality Database (HMD). Finally, for Russia we draw cause-specific mortality rates over 1994–2000 from the WHO database, and over 1965–1993 from Mesle et al. (1996). For 1959–1964 we add overall mortality rates from the HMD. For all countries, we calculate smoking-attributable mortality using non-smokers from the Cancer Prevention Study II as the reference population.

Finally, we compare smoking prevalence estimates from retrospective reports with estimates from prospective National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) data. The NHIS asks respondents whether they (currently) smoke regularly. These data are available over 1965–2005, except: 1967–69, 1971–73, 1975, 1981–82, 1984, 1986, 1989, 1996, 2004.

2.2. Adjustment for differential mortality on retrospective data

To create life-course smoking trajectories, we assume that a person smoked in each year from the age she started until either the age she quit (ex-smokers) or the year of the survey (current smokers). Due to lack of relevant information, we ignore any periods during which a person might have temporarily quit. With these data we construct a smoking-status indicator for every person-year observation, which equals 1 if that person smokes and 0 if she does not. We then identify members of the same sex who were born in different ten-year calendar periods. We measure smoking prevalence rates over the life-course as the mean smoking status in each year by gender and cohort (weighted by sampling weights).

Let PtT denote this prevalence; i.e. the proportion of smokers in t among individuals year interviewed in year T, with t ≤ T. We adjust this rate to account for the fact that smokers and non smokers die at different rates using the formula proposed by Harris. This formula implicitly assumes equal start and quit rates between survivor and non-survivor smokers and, thus, provides a lower bound for adjusted prevalence. The formula is as follows:

| (1) |

Ptt denotes the proportion of the population that smokes in year t (and survives until year t); and respectively denote the proportion of smokers and non-smokers who were alive in year t and who survived to answer the survey in year T.

We use richer and more precise estimates of the S variables. The bulk of the extant literature assumes that the ratio of the mortality rates of smokers and non smokers is constant over time and within broad age-categories. However, abundant evidence suggests it is not (Peto et al., 2006). To improve on this, we use the Peto et al. (1992) method to calculate the number of smoking-attributable deaths for each smoking-related disease by sex, year, and 5-year age category (if age>35). The Peto et al. method is straightforward to implement as it requires only widely available vital statistics, and its validity has been confirmed against other methods (Bronnum-Hansen and Juel, 2000; Preston et al., 2010). We then compute the death rate of non-smokers as the difference between all deaths and smoking-attributed deaths divided by the total population, and the death rate of smokers as the ratio of total deaths to the total population. Finally, we use these inputs to calculate survival probabilities by standard life-table techniques.

For the years when we have only overall mortality data, we assume that the relative mortality of smokers and non-smokers is time-invariant. We set this equal to the mean relative mortality by cohort and gender derived from the cause-specific data. For consistency with the Peto et al. procedure, we assume that smokers and non smokers younger than 35 both die at the same rate.

2.3. Comparison with cross-sectional data

As an additional exercise, we compare contemporaneously measured smoking prevalence rates with the equivalent rates from retrospective data. Kenkel et al. (2003) follow a similar strategy and find that retrospectively reported smoking behavior of young women matches reasonably well with that estimated from contemporaneous reports. We use this method with only the US NHIS data because we found no comparable series of UK or Russian surveys. We define contemporaneous smoking prevalence as the population share of each gender and age group that regularly smokes. With these data we construct cohort and sex-specific smoking trajectories that compare directly with the ones from the retrospective data.

Because cross-sectional data measure the current smoking status among people alive in the year of interest, one might presume that life-course smoking prevalence derived from repeated cross-sectional surveys reflect the “true” prevalence rate more accurately than that derived from retrospective data. However, differential mortality bias may affect cohort smoking histories in both prospective and retrospective study designs; both types of data fail to count smokers who die sooner. In both cases, a declining cohort prevalence over time reflects not only the increasing share of quitters, but also the decreasing share of surviving smokers relative to non-smokers.

Still, one cannot directly compare smoking prevalence derived from the two types of data. The contemporaneous data do not count as current smokers people who recently “quit” but who will later restart. Retrospective data may not count as smokers people who smoked only a few cigarettes on a daily basis (Kenkel et al. 2004). In both cases, smoking prevalence may be underestimated. A priori, it is not clear which type of missing smoker (temporary-quitter or light smoker) matters more. This depends on how much each type contributes to smoking-related mortality. The comparison of prevalence rates from the NHIS with both unadjusted and adjusted prevalence rates from the PSID can show which effect drives the data.

3. Results

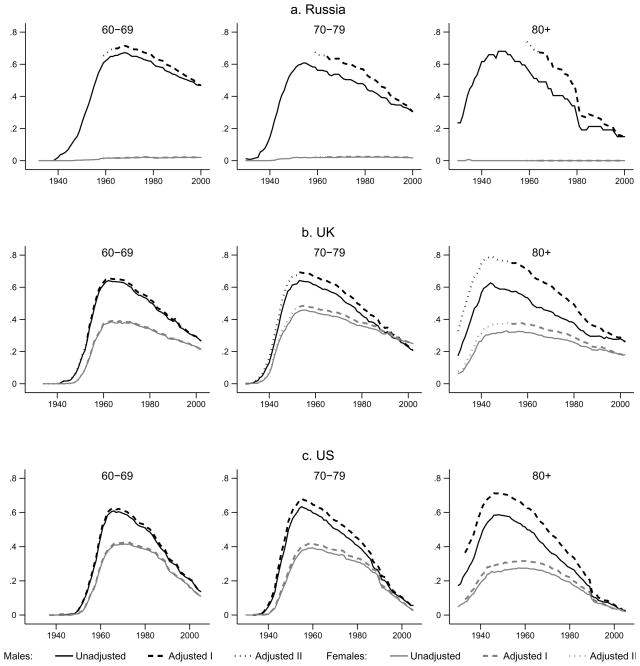

Figure 1 presents unadjusted and adjusted smoking prevalence rates over time by country, cohort, and gender. Our focus is on cohorts that, at the time of the survey, were ages 60–69, 70–79, and 80 and older. We do not present results for younger generations because smoking-related mortality differences are small and the adjustment has negligible effects. In each sub-figure, we plot the prevalence derived from the retrospective data as a solid line, the prevalence adjusted using the Peto et al. calculation as a dashed line (Adjusted I), and the prevalence adjusted using invariant mortality ratios as a dotted line (Adjusted II). Solid and non-solid lines overlap almost completely for the 60–69 generation in the UK and the US and for all generations of Russian women (whose smoking prevalence rates never exceed 2 percent). They diverge for US and UK men and women who are 70 and older, and all cohorts of Russian men. The adjustment appears to have the biggest effect in Russia, smaller in the UK, and smaller still in the US. While Russian women are clearly different, results are similar for women in the UK and the US.

Figure 1.

Correction of smoking prevalence for differential mortality by country, gender, birth cohort, and year (Smoking data are from: PSID, various waves; BHPS, 1999, 2002; RLMS 2000. Mortality data are from: WHO, US Bureau of Census, HMD, Mesle et al., various years)

Table 1 presents details of these findings and results from a standard test of independence for binary variables (Pearson χ2 with the Yates (1934) correction for small samples). The difference between unadjusted and adjusted prevalence appears largest for the oldest generation of Russian men (17 percentage points or 30 percent of unadjusted prevalence). The Pearson test, however, does not reject the hypothesis that the two rates are equal. The mean sample size of only 47 for this generation suggests that the test is under-powered. More power is available for Russian men aged 70–79. At the peak prevalence rate for this group, the two rates differ by 9 percentage points (15.5 percent of unadjusted prevalence). Unadjusted prevalence for this group is significantly underestimated in all years prior to 1977 when the average cohort member was 49 years old. The next two largest differences appear for the oldest cohorts of UK and US men. In those cohorts, at the peak smoking prevalence rate, the differences are 16 and 12 percentage points (25.4 percent and 19.3 percent), respectively. In both countries, unadjusted prevalence rates for these groups are significantly underestimated in all years prior to 1983, when the average cohort member was around 67 years old. In all other cases, differences between adjusted and unadjusted peak prevalence are statistically insignificant.

Table 1.

Summary of results (Smoking data are from: PSID, various waves; BHPS, 1999,2002; RLMS 2000. Mortality data are from: WHO, US Bureau of Census, HMD, Mesle et al., various years)

| Country | Gender | Cohort (age at interview) | Mean sample sizea | Peak unadjusted prevalence rate | Peak adjusted prevalence rate | Difference | Pearson χ2 test Statisticb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russiac | Males | 60–69 | 413 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.04 | 1.6 |

| 70–79 | 240 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 4.3 | ||

| 80+ | 47 | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 2.6 | ||

| Females | 60–69 | 663 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.0 | |

| 70–79 | 506 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.1 | ||

| 80+ | 165 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.0 | ||

| UK | Males | 60–69 | 467 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| 70–79 | 379 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 2.5 | ||

| 80+ | 223 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.14 | 17.5 | ||

| Females | 60–69 | 493 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.6 | |

| 70–79 | 457 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.6 | ||

| 80+ | 386 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 2.2 | ||

| US | Males | 60–69 | 565 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.4 |

| 70–79 | 421 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 2.1 | ||

| 80+ | 385 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 18.0 | ||

| Females | 60–69 | 552 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| 70–79 | 524 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.6 | ||

| 80+ | 549 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 2.4 | ||

Notes:

Average number of observations over available years;

Critical value at the 5% level of significance is 3.84;

For the two oldest Russian cohorts, for which we do not observe the peak prevalence, we report prevalence rates at the earliest available year.

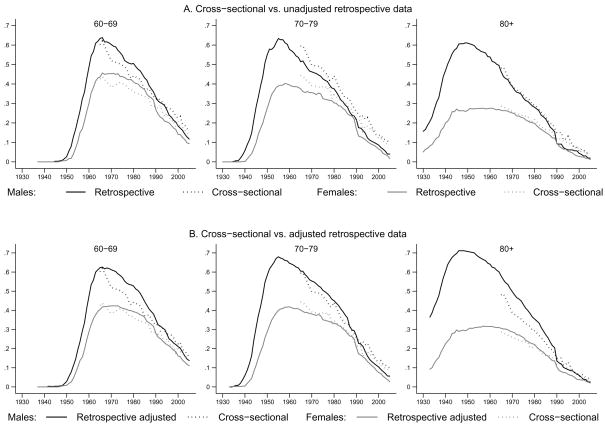

Finally, Figure 2 compares the contemporaneous smoking prevalence rate derived from cross-sectional data (dotted line) to the unadjusted (Panel A) and adjusted (Panel B) smoking prevalence rate derived from retrospective information (solid line). In Panel A, the dotted line appears over the solid line for the two oldest generations. This pattern would be consistent with the findings of Kenkel et al. (2004) if the members of these older cohorts were light smokers. Those authors found that people who reported smoking less than 6 cigarettes a day in contemporaneous survey data were more likely to retrospectively report that they had never smoked. The dotted line is somewhat lower than the solid line for 60–69 year-olds - a result consistent with the absence, in our retrospective data, of information on temporary abstinence from smoking (e.g. when we calculate cross-sectional prevalence counting as smokers those who quit smoking in the past 3 months, the rate increases by 1–2%). In Panel B, the dotted line appears lower than the solid line for all male cohorts, while differences for women shrink in most cases. This finding is in line with our earlier result that differential mortality bias significantly affects smoking prevalence for men but not for women.

Figure 2.

Comparison of life-time smoking prevalence rates derived from cross-sectional and retrospective data (Smoking data are from: PSID and NHIS, various waves. Mortality data are from: WHO and US Bureau of Census, various years)

4. Discussion

There are three important patterns in our results. First, correcting for differential mortality affects how peak smoking prevalence differs across birth cohorts, especially for men. While unadjusted peak prevalence follows no consistent pattern across cohorts, adjusted prevalence appears to be monotonically increasing with cohort age. Peak prevalence for men is, in fact, higher among older cohorts, thus the adjustment alters inferences one draws about historical patterns of smoking.

Second, the age at which mortality bias first matters differs by country. For UK and US retrospective data, the adjustment is not significant for anyone younger than 80 at interview. This finding is unsurprising given that, while smoking affects morbidity at younger ages, mortality rates of smokers and non smokers only start to diverge around age 70. However, for Russia, differential mortality starts to matter for younger generations. The finding of a significant bias for men aged 70–79, which is not observed in the US and UK, suggests that accounting for smoking related mortality is likely to be more important for developing countries or countries with less robust health care systems.

Finally, differential mortality matters only for men. We conjecture that this occurs not because women are immune to smoking-related diseases, but because of gender differences in tobacco use over time. As tobacco use increases, smoking-attributable mortality follows a hump-shaped pattern; it initially increases at a slow pace, then speeds up to a peak, and finally falls gradually to lower levels (Lopez et al., 1994). Thus, the mortality effects initially appear among groups who adopted smoking first (men). In groups that take up smoking later (women), effects should show up later. This also accounts for differences of bias found among US and UK women, and Russian women.

We re-emphasize that our estimates of adjusted smoking prevalence are conservative. One can read them as a lower bound of the true prevalence, since the adjustment assumes equal start and quit rates among smokers who survive and do not survive to answer the survey. In reality, non-survivors likely have different smoking preferences and face different cost of quitting than smokers who survive. The expectation is that non-survivor smokers are on average less likely to quit smoking and might also start smoking sooner than survivors.

5. Conclusion

Differential mortality of smokers and non-smokers affects our understanding of the smoking habits of old cohorts during youth and, therefore, of inter-generational patterns of smoking. It follows that, unless one focuses on the young, policy recommendations based on unadjusted smoking rates may be misleading. When data do not capture all smokers (survivors and non-survivors), derived inferences are not representative of the population. This conclusion is especially important for studies that analyze smoking prevalence at the cohort level (see citations in introduction), but also affects studies that examine how individual smoking behaviors vary with price (Douglas, 1998; Douglas and Hariharan, 1994; Foster and Jones, 2001; Kenkel et al., 2009; Nicolas, 2002), and whether smoking diffusion predicts mortality (Preston and Wang, 2006; Wang and Preston, 2009).

Our study is timely because of the growing number of surveys which ask respondents to retrospectively report on past smoking behavior. Such studies are ongoing or planned in the US (HRS), Europe (SHARE), United Kingdom (ELSA), Korea (KLSA), China (CHRLS), Indonesia (IFLS), and India (LASI). All of these surveys include or focus on respondents who are 50 year old or older. We have demonstrated how future users of such databases can benefit from the increasing availability of cause-specific mortality data to elaborately account for smoking-related mortality.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge research assistance from Karen Calabrese and funding from National Institute on Aging grants 1 R03 AG 021014-01 and 1 R01 AG030379-01A2. We are also grateful to M.J. Thun for generously providing us with the CPS-II 1982-88 cause-specific mortality data.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahacic K, Kennison R, Thorslung M. Trends in smoking in Sweden from 1968 to 2002: age, period and cohort patterns. Prev Med. 2008;46:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Burns DM. Patterns of adolescent smoking initiation rates by ethnicity and sex. Tob Control. 2000;9:ii4–ii8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_2.ii4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett NJ. Trends in smoking by birth cohort for births between 1940 and 1975: a reconstructed cohort analysis of the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. Prev Med. 1997;26:534–541. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner H. A birth cohort analysis of the smoking epidemic in West Germany. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1993;47:54–58. doi: 10.1136/jech.47.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronnum-Hansen H, Juel K. Estimating mortality due to cigarette smoking: two methods, same result. Epidemiology. 2000;11:422–426. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DM, Lee L, Shen LZ, Gilpin E, Tolley HD, Vaughn J, Shanks TG. Cigarette Smoking Behavior in the United States. In: Burns D, Garfinkel L, Samet J, editors. Changes in Cigarette-Related Disease Risk and Their Implications for Prevention and Control. Natl Inst Health; Bethesda: 1998. pp. 13–112. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S. The duration of the smoking habit. Econ Inq. 1998;36:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S, Hariharan G. The hazard of starting smoking: estimates from a split population duration model. J Health Econ. 1994;13:213–230. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo LG, Peddicord JP. Smoking prevalence in US birth cohorts: the influence of gender and education. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:231–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federico B, Costa G, Kunst AE. Educational inequalities in initiation, cessation, and prevalence of smoking among 3 Italian birth cohorts. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:838–845. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E, Schiaffino A, Borras JM, Shafey O, Villalbi JR, La Vecchia C. Prevalence of cigarette smoking by birth cohort among males and females in Spain, 1910–1990. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:57–62. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Jones A. The Role of Tobacco Taxes in Starting and Quitting Smoking: Duration Analysis of British Data. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 2001;164:517–547. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JE. Cigarette smoking among successive birth cohorts of men and women in the United States during 1900–80. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71:473–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. Trends in tobacco smoking and consequences on health in France. Prev Med. 1998;27:514–519. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemm JR. A birth cohort analysis of smoking by adults in Great Britain 1974–1998. J Public Health Med. 2001;23:306–311. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel D, Lillard DR, Liu F. An Analysis of Life-Course Smoking Behavior in China. Health Econ. 2009;18:S147–S156. doi: 10.1002/hec.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel D, Lillard DR, Mathios A. Smoke or Fire? Are Retrospective Smoking Data Valid? Addiction. 2003;98:1307–1313. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel D, Lillard DR, Mathios A. Accounting for Measurement Error in Retrospective Smoking Data. Health Econ. 2004;13:1031–1044. doi: 10.1002/hec.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen M, Uutela A, Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Helakorpi S, Puska P. Development of smoking by birth cohort in the adult population of Eastern Finland 1972–97. Tob Control. 1999;8:161–168. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vecchia C, Decarli A, Pagano R. Prevalence of cigarette smoking among subsequent cohorts of Italian males and females. Prev Med. 1986;15:606–613. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control. 1994;3:242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Marugame T, Kamo K, Sobue T, Akiba S, Mizuno S, Satoh H, Suzuki T, Tajima K, Tamakoshi A, Tsugane S. Trends in smoking by birth cohorts born between 1900 and 1977 in Japan. Prev Med. 2006;42:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes AM, Lopes MV, Hallal PC, Muino A, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, Val-divia G, Pertuze J, de Oca MM, Talamo C, Victora CG. Prevalence of smoking and incidence of initiation in the Latin American adult population: the PLATINO study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesle F, Shkolnikov V, Hertrich V, Vallin J. Tendances récentes de la mortalité par cause en Russie, 1965–1994 Données statistiques. Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED); Paris: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas AL. How Important Are Tobacco Prices in the Propensity to Start and Quit Smoking? An Analysis of Smoking Histories from the Spanish National Health Survey. Health Econ. 2002;11:521–535. doi: 10.1002/hec.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Koh HK, Kwon JW, Suh MK, Kim H, Cho SI. Secular trends in adult male smoking form 1992 to 2006 in South Korea: Age-specific changes with evolving tobacco-control policies. Public Health. 2009;123:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman F, Bobak M, Gilmore A, McKee M. Trends in the prevalence of smoking in Russia during the transition to a market economy. Tob Control. 2007;16:299–305. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries, 1950–2000. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C. Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet. 1992;339:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91600-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Glei DA, Wilmoth JR. A new method for estimating smoking-attributable mortality in high income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:430–438. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Wang H. Sex Mortality Differences in the United States: The Role of Cohort Smoking Patterns. Demography. 2006;43:631–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberg A, Lund KE, Hafstad A. Lifetime smoking habits among Norwegian men and women born between 1890 and 1974. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:267–276. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of the Census, various years. Vital Statistics of the United States. United States Government Printing Office; Washington: [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Preston SH. Forecasting United States mortality using cohort smoking histories. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:393–398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811809106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE. Effects of the antismoking campaign: an update. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:144–151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates F. Contingency table involving small numbers and the χ2 test. Supplement to J R Stat Soc. 1934;1:217–235. [Google Scholar]