Abstract

Very-long-term (VLT) chromatic adaptation results from exposure to an altered chromatic environment for days or weeks. Color shifts from VLT adaptation are observed hours or days after leaving the altered environment. Short-term chromatic adaptation, on the other hand, results from exposure for a few minutes or less, with color shifts measured within seconds or a few minutes after the adapting light is extinguished; recovery to the pre-adapted state is complete in less than an hour. Here, both types of adaptation were combined. All adaptation was to reddish-appearing long-wavelength light. Shifts in unique yellow were measured following adaptation. Previous studies demonstrate shifts in unique yellow due to VLT chromatic adaptation, but shifts from short-term chromatic adaptation to comparable adapting light can be far greater than from VLT adaptation. The question considered here is whether the color shifts from VLT adaptation are cumulative with large shifts from short-term adaptation or, alternatively, does simultaneous short-term adaptation eliminate color shifts caused by VLT adaptation. The results show the color shifts from VLT and short-term adaptation together are cumulative, which indicates that both short-term and very-long-term chromatic adaptation affect color perception during natural viewing.

Keywords: Chromatic adaptation, equilibrium yellow, equilibrium hue, long-term adaptation

INTRODUCTION

Chromatic adaptation from viewing light of selective wavelengths causes reversible changes in color appearance. Chromatic adaptation for a few seconds or minutes (short-term adaptation) or for days or weeks (very-long-term adaptation) has been studied experimentally, but the work here is the first to study shifts in color appearance when both types of adaptation are combined.

Short-term adaptation is a well-studied phenomenon. It results from exposure of 15 minutes or less to a chromatic light. The adapting effect decays within seconds or minutes (Jameson, Hurvich & Vaner, 1979; Rinner & Gegenfurtner, 2000). Many studies support a two-process model of short-term chromatic adaptation (Jameson & Hurvich, 1972; Cicerone et al., 1975; Shevell, 1978; Guth et al., 1980; Drum, 1981; Larimer 1981; Ware & Cowan, 1982; Hayhoe & Wenderoth, 1991).

Very-long-term (VLT) chromatic adaptation has been little studied until recently. It results from exposure to an altered chromatic environment for an hour or more each day over many days or weeks. Several adapting techniques have been used, including natural viewing with chromatically selective (typically long-wave-transmitting) lenses (Eisner & Enoch, 1982; Neitz et al., 2002; Yamauchi et al., 2002) or with a spectrally filtered illuminant that predominantly emits long wavelengths (Neitz et al., 2002; Belmore & Shevell, 2008). VLT adaptation can be induced also by viewing a long-wavelength grating on a video display for an hour each day (a technique suggested to us by Dr. J. Neitz). Different VLT-adapting methods and durations produce similar shifts in unique yellow, which are maintained for days or even weeks after the end of the adapting period (Neitz et al., 2002; Belmore & Shevell, 2008).

The color shifts from VLT adaptation cannot be fully explained by a gain (von Kries) theory of adaptation (Belmore & Shevell, 2008). As with short-term chromatic adaptation, VLT adaptation causes shifts in unique yellow consistent with a two-process model.

VLT and short-term adaptation often have been distinguished by the temporal properties of the color shifts resulting from the adaptation. VLT adaptation is characterized by color changes (i) that can increase in magnitude with recurring exposure to the adapting light over several days or longer and (ii) that persist for tens of hours, days or even weeks after chromatic adaptation ends. Short-term adaptation typically is assumed to reach its asymptotic impact within an hour or less of viewing the adapting stimulus, and any effect of adaptation is presumed (though seldom demonstrated) to dissipate within an hour. The different time courses for the influence of VLT versus short-term adaptation suggest distinct neural mechanisms, which may be isolated to a significant degree with carefully chosen adapting durations and testing periods. Both mechanisms, however, conceivably may drive a common, higher-level neural pathway that mediates the color shifts caused by either type of adaptation. Even though each type of adaptation may be initiated by a separate mechanism with distinct temporal properties, if they share a later nonlinear neural pathway then one type of adaptation may completely dominate the other. If so, VLT adaptation may not affect color perception in natural viewing when both short-term and VLT adaptation occur simultaneously.

In general, the relative strength of VLT versus short-term chromatic adaptation is not easily determined. Under some comparable conditions, for example exposure to a long-wavelength adapting light in the laboratory, short-term chromatic adaptation can produce a shift in equilibrium (neither reddish nor greenish) yellow far greater than that produced by VLT adaptation. Consider a test stimulus that is an admixture of 540 and 660 nm light. With the level of the 540 nm light fixed, the observer sets the radiance of the 660 nm component so the test appears equilibrium yellow. Introducing short-term long-wavelength chromatic adapting light can increase the required 660 nm radiance by a full log unit, but VLT adaptation may raise the 660 nm level by as little as 0.1 log unit. Laboratory measurements of VLT adaptation, however, do not extend for a sufficiently long period of time to examine VLT-adapting mechanisms that may depend on light stimulation over months or longer. Also, other color-measurement paradigms may yield a different relative contribution from short-term versus VLT adaptation. A challenge, therefore, is to assess whether color shifts from short-term and VLT adaptation are cumulative without having to determine a “baseline” state of color perception without VLT adaptation.

The aim of this study was to assess whether the color shifts found in laboratory experiments of VLT adaptation are important for natural viewing. This can be determined without knowing the absolute magnitude of the color changes that may result from VLT adaptation. The critical question is whether the color shifts induced by VLT laboratory adaptation are the same, with or without short-term adaptation that alone causes large color shifts; that is, are the color shifts from short-term and VLT adaptation cumulative even when short-term adaptation causes a much larger change in color appearance than VLT adaptation? If so, then laboratory studies of VLT adaptation reveal a neural process of color perception whose effect survives even in the presence of far larger color shifts due to short-term adaptation, and thus reveal an important neural process in natural viewing.

METHODS

Overview of procedure

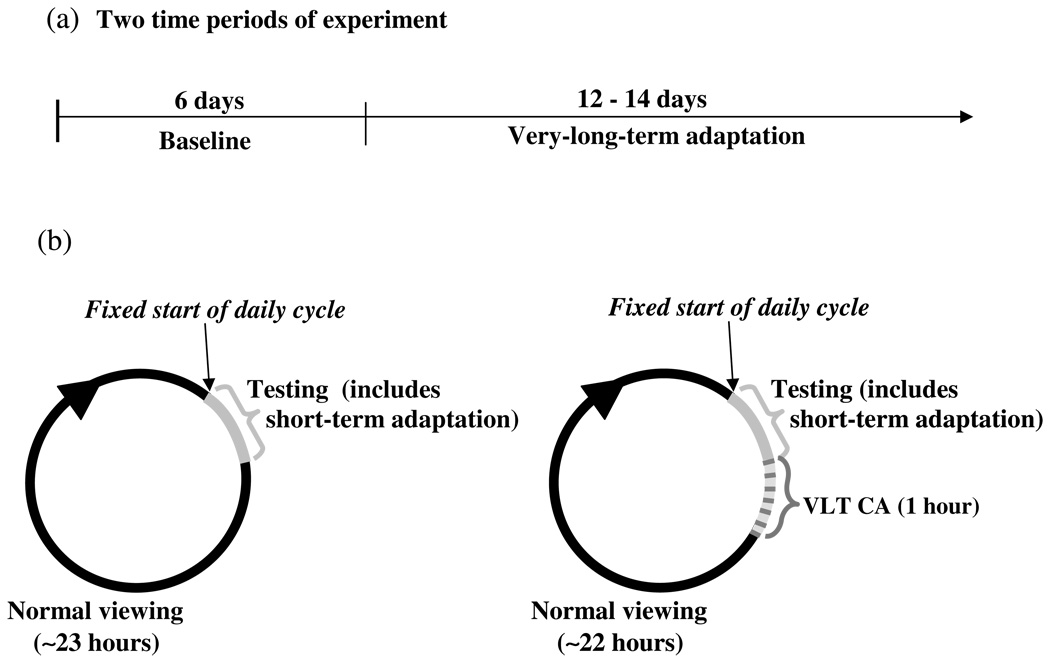

The experiment was divided into two contiguous time periods: a baseline period followed by VLT chromatic adaptation (Figs. 1a,b). During both periods, the observer made equilibrium yellow measurements at approximately the same time each day. Two sets of baseline measurements were taken during the first six days of the experiment. One set immediately followed dark adaptation, and then another set was taken during short-term chromatic adaptation. At the end of the testing session on the sixth day, the observer began the VLT chromatic adaptation, which lasted one hour. On the following (seventh) day, testing began at least 22 hours after the end of the previous day’s VLT adaptation. This sequence of taking equilibrium-yellow measurements and then, immediately afterward, one hour of VLT adaptation continued for 12 or 14 days.

Figure 1.

(a) The two consecutive experimental time periods during which equilibrium yellow measurements were obtained. (b) The daily cycle of testing, VLT adaptation and normal viewing. The daily cycle for each observer began at approximately the same time each day throughout the experiment.

Adapting stimuli

The stimulus for VLT chromatic adaptation was a grating pattern (Fig. 2a) presented for one hour each day on a cathode ray tube (CRT) video display in an otherwise dark, windowless room. The screen displayed randomly located, parallel lines of some orientation; a new set of lines at a different randomly chosen orientation was presented every five seconds. The width of each line was approximately 10 min of arc. The line density covered 25% of the area of the display. Judd chromaticity coordinates for the lines were (x=0.60, y=0.35) at 22.4 cd/m2. The display, a carefully calibrated Sony Triniton monitor (GDM-F520), was controlled by a Macintosh G4 computer. The CRT display was set via software for 1360×1024 pixel resolution and a refresh rate of 75 Hz noninterlaced.

Figure 2.

(a) Example of CRT display for very-long-term chromatic adaptation (see text). (b) Test stimulus presentation sequence for conditions that included short-term chromatic adaptation (see text).

Short-term chromatic adaptation took place during the testing session as part of the test-stimulus presentation, using a Maxwellian-view optical system. The short-term adapting field was a 660 nm, 2.7 deg diameter disk at 100 td. At this light level, the additive and gain components that account for color perception under short-term adaptation are well differentiated (Shevell, 1982). Initially, the observer viewed this adapting field for three minutes; later, it was presented as part of the test-field presentation sequence (see “Test stimulus” below), which ensured that short-term adaptation was maintained throughout those equilibrium-yellow measurements.

Test stimulus

The test field for assessing equilibrium yellow was an annulus of inner-outer diameter 0.8 – 1.3 deg presented using the Maxwellian-view system. The observer viewed the field with the right eye. The test was composed of an admixture of 540 nm and 660 nm lights. The observer adjusted the level of the 660 nm light so the test appeared equilibrium (neither reddish nor greenish) yellow. The 540 nm component was fixed in retinal illuminance on each trial; the levels of 540 nm tested within each session were 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 log td (a 2.5 log td level was added for the combined-adaptation measurements).

For the combined-adaptation condition, or short-term adaptation alone, short-term chromatic adaptation was maintained with a repeating four-second cycle of stimulus presentation. The test field was presented alone for one second and then was presented superimposed on the adapting field for three seconds. The observer judged the color of the test during only the one-second test-alone presentation. The stimulus presentation sequence is diagrammed in Fig. 2b.

Procedure

In testing sessions, unique yellow measurements began at the lowest 540 nm light level and ended with the highest. The observer used a game pad to adjust the radiance of the 660 nm light in the admixture to achieve a percept that was neither reddish nor greenish. There were five trials at each 540 nm level in the test; measurements from the five trials were averaged. This protocol is similar to one used by Shevell (1982) in studies of color perception with a short-term chromatic adapting field. Both observers were practiced at setting equilibrium yellow before the start of data collection.

Each set of measurements began with five minutes of dark adaptation. Then measurements were taken for VLT adaptation alone (or, during the baseline period, for dark adaptation). There was one minute of further dark adaptation before measurements were taken at each new level of 540 nm light in the test field. An additional three minutes of dark adaptation preceded the following measurements that included short-term chromatic adaptation. An initial three-minute period of exposure to the short-term chromatic adapting field preceded short-term-adaptation measurements.

Observers

Observers were two University of Chicago undergraduate students. They were naïve about the purpose of the experiment and were paid for their participation. Both observers had normal color vision as assessed by Rayleigh matching using a Neitz anomaloscope. Consent forms were completed in accordance with the policy of the University of Chicago’s institutional review board.

RESULTS

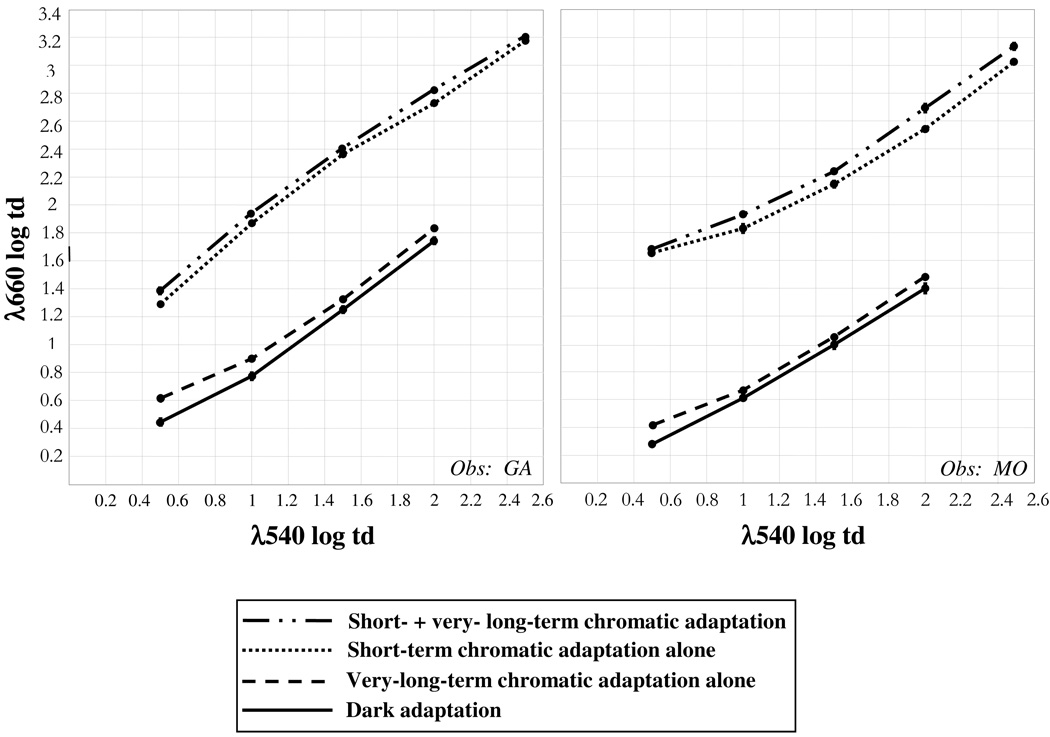

Either VLT or short-term chromatic adaptation shifted color perception. Following either type of adaptation, the amount of 660 nm light in the test field had to be increased for the percept of equilibrium yellow, compared to dark adaptation. These measurements are shown in Fig. 3 for each level of 540 nm light in the test field (horizontal axis), for dark adaptation (solid line), VLT adaptation alone (dashed line) and short-term adaptation alone (dotted line). Each plotted value is the average of measurements made on many days. Error bars show standard errors of the mean, though most of them are smaller than the plotted point so are not visible. Each panel shows results for a different observer.

Figure 3.

Average measurements of equilibrium yellow during the baseline and very-long-term chromatic adaptation experimental periods. Baseline measurements: dark adaptation (solid line) and short-term chromatic adaptation alone (dotted line). Shifts in unique yellow due to introducing very-long-term adaptation: VLT adaptation alone (dashed line); VLT together with short-term adaptation (dash-dot line). The amount of 660 nm test light (vertical axis) needed to establish equilibrium yellow is given as a function of the amount of 540 nm test light (horizontal axis).

The main aim of this experiment was to compare the color shifts with combined VLT and short-term chromatic adaptation to shifts with either type of adaptation alone. Measurements with combined adaptation (dash-dot line, Fig. 3) fall above the shifts found with short-term chromatic adaptation (dotted line); this shows that adding VLT chromatic adaptation increased the color shifts beyond those due to short-term adaptation alone (p<0.01 for each observer by Tukey HSD test, comparing the four types of adaptation: dark, short-term alone, VLT alone and combined). VLT adaptation alone (dashed line) also caused a color shift compared to dark adaptation (solid line; p<0.01 for each observer by Tukey HSD test). Furthermore, the magnitude of the average shift from VLT adaptation alone compared to dark adaptation (0.12 log td for Obs. G.A., 0.09 log td for M.O.) was comparable to the shift from combined adaptation compared to short-term adaptation alone (0.08 log td for G.A., 0.09 log td for M.O.). Thus, the shifts in equilibrium yellow produced by short-term and VLT adaptation together were cumulative; this shows that VLT adaptation can significantly affect color perception in natural viewing where, of course, VLT and short-term adaptation operate simultaneously.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, there is no previous comparison of the color shifts from VLT chromatic adaptation combined with short-term adaptation, to the color shifts from short-term adaptation alone. The results here showed that the color shifts caused by short-term and VLT chromatic adaptation together were cumulative. The incremental shift due to VLT adaptation was very similar whether or not the observer also was exposed to short-term adaptation.

While the results from short-term and VLT adaptation are additive, this additivity does not imply separate, independent neural mechanisms. Consider for example a single linear process, such that introducing adapting stimulus A results in a color shift of magnitude S, regardless of the initial adapted state (and thus of any color shift already induced) when A is introduced. This single mechanism could account for the cumulative color shifts found with combined short-term and VLT adaptation. Nonetheless, distinct short-term and VLT neural mechanisms are supported by other properties of the color shifts they induce. Color shifts from VLT adaptation, but not short-term adaptation, increase with additional adaptation over many days; and the color shifts from VLT adaptation, but not short-term adaptation, persist for days after the adaptation ends (Neitz et al., 2002). The question of independent mechanisms for each type of adaptation, however, is not the focus here, because even fully independent mechanisms at one stage of the visual system may interfere with each other. As mentioned earlier, if short-term and VLT chromatic-adaptation mechanisms converge on a later nonlinear neural mechanism or some other bottleneck, then short-term chromatic adaptation could saturate or otherwise inhibit neural responses that mediate color shifts from VLT adaptation alone.

Different processes of adaptation have been described at many levels of the visual system. A classical distinction is photochemical (pigment bleaching; Wyszecki & Stiles, 1980) versus neural processes of adaptation, and of course there is a variety of different neural mechanisms. For example, two distinct mechanisms are posited to explain color shifts that persist for a longer duration following a 10-sec-on/10-sec-off chromatic adapting cycle (0.05 Hz), compared to presenting the same adapting light continuously (Jameson, Hurvich & Varner, 1979). Within the realm of neural adaptation, some mechanisms depend on the space-average or time-average of the adapting stimulus (Valberg & Lange-Malecki, 1990; Fairchild & Lennie, 1992; Webster & Wilson, 2000), while other mechanisms are driven by the variation in the adapting stimulus over space (Brown & MacLeod, 1997; Shevell & Wei, 1998; Monnier & Shevell, 2003) or time (Webster & Mollon, 1991; 1994).

Additional evidence in support of multiple mechanisms comes from the observation that a given long-wavelength adapting light can shift color appearance toward either greenness or redness, depending on whether the light is presented to the same eye as the test, as is typical, or to only the contralateral eye (Shevell & Humanski, 1984); presumably, the contralateral stimulus drives only a central neural mechanism while the same-eye adapting field affects also retinal mechanisms of adaptation that influence the neural representation of the test field. In addition, separate mechanisms are revealed by their distinct time scales (Vul, Krizay & MacLeod, 2008; Webster & Leonard, 2008). Multiple, hierarchical mechanisms of adaptation are posited even for short-term adaptation to a steadily presented adapting field in the same eye as the test (Rinner & Gegenfurtner, 2000).

Given the broad evidence for multiple mechanisms of adaptation, it may not be considered surprising that short-term and VLT chromatic adaptation act cumulatively. Isolating distinct mechanisms, however, does not guarantee that each one has an influence on color perception when other mechanisms are also active. The findings here show the importance of understanding VLT adaptation because the color shifts it causes persist even with strong, simultaneous short-term chromatic adaptation.

Research Highlights

-

*

Changes in color appearance following very-long-term (VLT) chromatic adaptation (for days or weeks) were studied in combination with more typical short-term chromatic adaptation.

-

*

Changes in color appearance caused by VLT chromatic adaptation can be substantially smaller than from short-term adaptation. If both types of adaptation depend on mechanisms that later converge on a common nonlinear pathway, then short-term adaptation may dominate or eliminate color shifts from VLT adaptation. This would imply color shifts from VLT adaptation may be unimportant in natural viewing.

-

*

Color shifts were measured with short-term adaptation alone, VLT adaptation alone, and combined VLT + short-term adaptation. The results show the color shifts from VLT and short-term adaptation are cumulative; that is, the color shifts from VLT adaptation added to the shifts from short-term adaptation, which reveals the importance of VLT adaptation in natural viewing.

-

*

Note: The experimental results are presented in one figure but they represent measurements made in several conditions during periods of adaptation and testing that went on for several weeks. We believe they make an important point about the significance of VLT adaptation for color perception.

Acknowledgement

Supported by NIH grant EY-04802.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Belmore SC, Shevell SK. Very-long-term chromatic adaptation: test of gain theory and a new method. Visual Neuroscience. 2008;25:411–414. doi: 10.1017/S0952523808080450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RO, MacLeod DIA. Color appearance depends on the variance of surround colors. Current Biology. 1997;7:844–849. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen JH, D'Antona AD, Shevell SK. The neural pathways mediating color shifts induced by temporally varying light. Journal of Vision. 2009;9(5):1–10. doi: 10.1167/9.5.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone CM, Krantz DH, Larmier J. Opponent-process additivity III: Effects of moderal chromtic adaptation. Vision Research. 1975;15:1125–1135. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(75)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drum B. Additive effect of backgrounds in chromatic induction. Vision Research. 1981;21:959–961. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner A, Enoch JM. Some effects of 1 week's monocular exposure to long-wavelength stimuli. Perception and Psychophysics. 1982;31:169–174. doi: 10.3758/bf03206217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild MD, Lennie P. Chromatic adaptation to natural and incandescent illuminants. Vision Research. 1992;32:2077–2085. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90069-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth SL, Massof RW, Benzschawel T. Vector model for normal and dichromatic color vision. Journal of the Optical Society of America. 1980;70:197–212. doi: 10.1364/josa.70.000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayhoe M, Wenderoth P. Adaptation mechanisms in color and brightness. In: Valberg A, Lee BB, editors. From Pigments to Perception. New York: Plenum; 1991. pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson D, Hurvich LM, Varner FD. Receptoral and postrecptoral visual processes in recovery from chromatic adaptation. Proceedings National Academy of Sciences USA. 1979;76:3034–3038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson D, Hurvich LM. Color adaptation: sensitivity, contrast and afterimages. In: Jameson D, Hurvich LM, editors. Handbook of sensory physiology Vol. VII/4. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1972. pp. 568–581. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer J. Red/green opponent colors equilibria measured on chromatic adapting fields: evidence for gain changes and restoring forces. Vision Research. 1981;14:1127–1140. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier P, Shevell SK. Large shifts in color appearance from patterned chromatic backgrounds. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:801–802. doi: 10.1038/nn1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neitz J, Carroll J, Yamauchi Y, Neitz M, Williams DR. Color perception is mediated by a plastic neural mechanism that is adjustable in adults. Neuron. 2002;15:783–792. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinner O, Gegenfurtner KR. Time course of chromatic adaptation for color appearance and discrimination. Vision Research. 2000;40:1813–1826. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell SK. The dual role of chromatic backgrounds in color perception. Vision Research. 1978;18:1649–1661. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell SK. Color perception under chromatic adaptation: equilibrium yellow and long-wavelength adaptation. Vision Research. 1982;22:279–292. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell SK, Humanski RA. Color perception under contralateral and binocularly fused chromatic adaptation. Vision Research. 1984;24:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell SK, Wei J. Chromatic induction: Border contrast or adaptation to surrounding light. Vision Research. 1998;38:1561–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valberg A, Lange-Malecki B. “Colour constancy” in Mondrian Patterns: A partical cancellation of physical chromaticity shifts by simultaneous contrast. Vision Research. 1990;30:371–380. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90079-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vul E, Krizay E, MacLeod DIA. The McCollough effect reflects permanent and transient adaptation in early visual cortex. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(12):1–12. doi: 10.1167/8.12.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware C, Cowan WB. Changes in perceived color due to chromatic interactions. Vision Research. 1982;22:1035–1062. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Leonard D. Adaptation and perceptual norms in color vision. Journal of the Optical Society of America A. 2008;25:2817–2815. doi: 10.1364/josaa.25.002817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Mollon JD. Changes in colour appearance following postreceptoral adaptation. Nature. 1991;349:235–238. doi: 10.1038/349235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Mollon JD. The influence of contrast adaptation on color appearance. Vision Research. 1994;34:1993–2020. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Wilson JA. Interactions between chromatic adaptation and contrast adaptation in color appearance. Vision Research. 2000;40:3801–3816. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyszecki G, Stiles WS. High-level trichromatic color matching and the pigment-bleaching hypothesis. Vision Research. 1980;20:23–37. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(80)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y, Williams DR, Brainard DH, Roorda A, Carroll J, Neitz M, Neitz J, Calderone JB, Jacobs GH. What determines unique yellow, L/M cone ratio or visual experience?. Paper presented at the 9th Congress of the International Colour Association, Proceedings of SPIE; 2002. pp. 275–278. [Google Scholar]