Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We assessed the incidence and outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy for patients with a pre-operative benign diagnosis and in patients who had an unexpected diagnosis of benign disease following resection. We have also compared how the introduction of endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has altered our pre-operative assessment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between January 1997 and April 2006, 499 patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Data were collected prospectively. A further 85 patients between 2006 and 2008 had a different diagnostic approach (after imaging these patients have been also studied by EUS-FNA).

RESULTS

Overall, 78 (15.6%) patients had no malignant disease on final histology. Out of 459 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for presumed malignancy, 49 (10.6%) had benign disease (sensitivity, 97%; positive predictive value, 89%). In a further 40 patients with a pre-operative benign diagnosis, we found 11 cases (27%) of malignancy (sensitivity, 37%; negative predictive value, 72%). Following the introduction of EUS-FNA, the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic work were 92% and 75%, respectively (positive predictive value, 93%; negative predictive value, 63%). The median follow-up was 35 months (range, 1–116 months).

CONCLUSIONS

Prior to the introduction of EUS-FNA, a significant number of patients, in whom pancreaticoduodenectomy is carried out for suspected benign disease, turn out to have an underlying malignancy. The use of EUS-FNA has improved the specificity of diagnostic work-up.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Benign disease, Chronic pancreatitis, Uncertain lesion head of pancreas, Diagnosis

Following its introduction by Kausch1 in 1930 and Whipple2 in 1935, the operation of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) has now become standard treatment for malignant, and occasionally benign, pathology of the head of the pancreas and peri-ampullary region. Historically, PD has been a high-risk procedure associated with considerable mortality and morbidity;3 however, improvements in surgical technique and postoperative care have led to better outcomes. In several centres, the mortality rate is less then 5%,4,5 with a few centres reporting large series without any deaths, although morbidity continues to be as high as 25%.6 It is well recognised that a small percentage of patients who undergo PD for suspected cancer will turn out to have benign pathology. The pathology in these fortunate patients is diverse and includes tuberculosis,7 foreign body or Crohn's disease-associated granulomas,8,9 eosinophilic pancreatitis,10 focal inflammatory ‘pseudotumour’,11 heterotopic pancreatitis,12 annular pancreas,13 localised sclerosing cholangitis14 or autoimmune pancreatitis.15–17

The purpose of this study was to audit the incidence of benign disease in patients who underwent PD, and analyse those patients in whom postoperative histology was different to the expected pre-operative diagnosis. The second aim was to examine how the introduction of EUS changed the diagnostic work-up in pre-operative assessment.

Patients and Methods

All patients undergoing PD at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, between January 1997 and April 2006 were retrospectively analysed from a collected departmental database. Past medical history (including alcohol abuse and diabetes) and diagnostic pathways and procedural details (including complications) were collected from the database and, where necessary, from medical records. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee.

The outcome measures studied included morbidity, mortality and overall survival. All specimens were evaluated in our histopathology department using standard haematoxylin and eosin processing and immunohis to chemistry where necessary. For the purpose of the study, pathological specimens were reviewed by a pathologist blind to the patient details and final diagnosis.

Patients underwent regular follow-up where possible. Pre-operative investigations included abdominal ultra-sonography, contrast enhanced (arterial and portal venous phase) computerised tomography (CT), and, in selected cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to delineate accurately tumour size, local disease stage and the presence of metastatic disease. Endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopancreatography (ERCP) was used in selected jaundiced patients to achieve biliary stenting and provided samples for cytology and histology. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) was introduced routinely in April 2006. In patients presenting with ampullary or duodenal adenomas, PD was carried out if the pre-operative histology showed features of severe dysplasia or if patients presented with obstructive jaundice provided that patients were considered fit enough to undergo PD. In patients with mild or moderate dysplasia or those not fit enough for PD, a transduodenal local excision was considered. Patients with cystic lesions were considered for PD if they presented with a clinical picture and imaging suggestive of a premalignant lesion. Since 2006, we have used EUS and cytology/tumour markers to determine which patients should be treated with resection. All imaging was discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and recorded on the database.

In the first part of the study, we selected those patients without malignancy in the surgical specimen (i.e. ‘the benign group’) and studied them collectively. In the second part of the study, we looked at two separate cohorts; those who turned out to have a malignancy in the surgical resection specimen despite a pre-operative diagnosis of benign pancreatic disease (i.e. the ‘false negatives’ of the diagnostic work-up) and those who underwent PD for strong suspicion of malignancy but were found to have no malignancy on histology (i.e. the ‘false positives’).

Finally, we analysed how the introduction of EUS-FNA had altered practice. Histological findings obtained by EUS-FNA from April 2006 to June 2008 were compared with the final diagnosis assessed by surgery.

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. To estimate the utility of our diagnostic work-up, we used diagnostic statistics, calculating, sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values. For categorical variable analysis, we used Fisher's exact test. The program used was SPSSRRR v.13.0 (SPSS, 233 South Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

Results

Benign subgroup analysis

Between January 1997 and April 2006, 499 PDs were performed at the Liver Unit, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham. Of these, 78 (15.6%; 46 male; median age, 59 years; range, 18–86 years) patients were negative for malignant disease on final histology, i.e. the ‘benign group’. The median follow-up was 35 months (range, 1–116 months). The indications for surgery based on pre-operative imaging were: suspected ampullary carcinoma in 15 patients (19.2%); cystic or solid tumour in the head of pancreas (HOP) in 6 (7.6%) and 26 (31%), respectively; ampullary or duodenal adenoma in 10 (12.8%); bile duct stricture in 8 (10.3%); CP in 13 patients (16.7%) as summarised in Table 1. A pylorus-preserving PD was performed in 68 (86%) patients (including one patient in whom portal vein resection was carried out because of hard adhesion between parenchyma and portal vein due to severe CP), while 10 patients (12.8%) had a conventional Whipple procedure.

Table 1.

Indications for pancreaticoduodenectomy for the 78 patients with no malignancy at final histology

| Indications for surgery | Pre-operative MDT diagnosis | True negative | False positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic/HOP mass | Benign | 6 | – |

| Mass/tumour HOP mass | Malignancy | – | 26 |

| Ca of amp/duo | Malignancy | – | 15 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | Benign | 13 | – |

| Adenoma of amp/duo | Benign | 10 | – |

| CBD stricture | Malignancy | – | 8 |

| Total | 29 | 49 |

HOP, head of pancreas; Ca of amp/duo, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla or duodenum; Adenoma of amp/duo, adenoma of ampulla or duodenum; CBD, common bile duct stricture; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Of the patients, 76% (n = 59) did not have a peri-operative blood transfusion and 59% (n = 46) of the patients had no postoperative complications. A pancreatic leak occurred in four (5.1%) patients and a bile leak in two (2.5%). Four (5.1%) patients developed wound infections, one (1.2%) a pulmonary complication and two (2.5%) had an intra-abdominal abscess. The overall median postoperative stay was 10 days (range, 6–65 days). There were five (6.4%) deaths within 30 days of surgery, due to sepsis multi-organ failure in three (3.8%; one with a pancreatic leak), massive gastrointestinal bleeding from entero-entero anastomosis in one (1.2%), and primary bleeding requiring two re-laparotomies followed by sepsis and multi-organ failure in one (1.2%). The overall 5-year survival rate in the 78 benign disease patients was 83.3% with no difference between patients with CP and other benign disease (P = 0.09).

The final pathological diagnosis in these 78 patients revealed CP in 35 (44.8%) patients and 43 (55.2%) patients had other benign conditions, i.e. serous cyst adenoma (n = 19; 24.3%), inflammatory bile duct stricture (n = 10; 12.8%) and other rare benign diseases in 14 (18%) patients (Table 2). A review of relevant past medical histories (PMHs) revealed five (6.4%) patients with a history of CP; six (7.7%) patients had a history suggestive of alcohol abuse; three patients (3.8%) had had previous pancreatic surgery (one Puestow procedure and two distal pancreatectomies performed for the treatment of symptomatic chronic pancreatitis with therapy resistant pain).

Table 2.

Final diagnosis (on histology) of the 78 patients in our series with benign disease

| Histological findings | Number | Overall %* |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic pancreatitis | 35 | 7 |

| Benign serous cystadenoma | 19 | 3.8 |

| Benign CBD stricture | 10 | 2 |

| Rare benign disease | 14 | 2.8 |

| Adenomyoma ampulla | 1 | 0.2 |

| Para-ampullary cyst | 1 | 0.2 |

| Choledochal cyst | 1 | 0.2 |

| Pseudotumour | 2 | 0.4 |

| Gardener's syndrome | 1 | 0.2 |

| Chronic inflammation ampulla | 1 | 0.2 |

| Papillary hyperplasia | 1 | 0.2 |

| Vas malformation CBD | 1 | 0.2 |

| Duodenal adenoma | 1 | 0.2 |

| Bile duct papilloma | 2 | 0.4 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 1 | 0.2 |

Overall % of patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy

FALSE-NEGATIVE SUBGROUP ANALYSIS

A total of 40/499 (8%) patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of benign pathology (14 CP, 14 ampullary or duodenal adenomas, 12 pancreatic cysts). The final histology confirmed the pre-operative diagnosis in 29 cases (73%) – 12 patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of CP, 9 ampullary or duodenal adenomas, 8 pancreatic cyst) and reported malignancy in 11 cases (27%). In the 14 with the pre-operative diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, the final pathology revealed adenocarcinoma in one patient and non-functioning endocrine tumour with malignant features in another. Among the 14 who had a diagnosis of ampullary or duodenal adenomas, final histology revealed three cases of ampullary carcinoma (pre-operative ERCP biopsies in these three patients had shown two patients with ampullary adenomas with mild dysplasia and one with a villous adenoma of the duodenum) and two cases of adenocarcinomas (pre-operative ERCP biopsies in these two had shown ampullary adenomas again, both with mild grade dysplasia).

In the 12 patients with pancreatic cysts, there were two cystadenocarcinomas (CyAdCa) arising from intrapapillary mucinous neoplasm, one acinar carcinoma and one solid/cystic papillary cystic adenocarcinoma (solid PapCyCa). The CT scans in those with CyAdCa, showed simple cysts in HOP in both with negative ERCP brush cytology. In patients with solid PapCyCa and acinar cell carcinoma, a large simple cyst was found on imaging with negative ERCP brushings in both (Table 3).

Table 3.

Details of histological findings in the 11 patients in whom pancreaticoduodenectomy was carried out for presumed benign disease with an unsuspected underlying malignancy found at histology

| Age (yrs) | Sex | Main symptoms | MDT diagnosis | Histo | Grading (cm) | TNM | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 82 | F | Jaundice | Adenoma duodeno | Ampullary carcinoma | Well diff | pT1N0 | 0.6 |

| 63 | F | Asymptomatic | Ampullary adenoma, mild dysplasia | Ampullary carcinoma | Mod diff | pT1N0 | 1.2 |

| 57 | M | Abdominal pain | Ampullary adenoma, mild dysplasia | Ampullary carcinoma | Mod diff | pT2N0 | 1.2 |

| 55 | M | Abdominal pain | Ampullary adenoma, mild dysplasia | Ampullary carcinoma | Mod diff | pT2N0 | 2.5 |

| 75 | M | Abdominal pain | Ampullary adenoma, mild dysplasia | Adenocarcinoma | Poorly diff | pT3N1 | 3.5 |

| 75 | F | Abdominal pain | Chronic pancreatitis | Adenocarcinoma | Mod diff | pT3N1 | 3.5 |

| 59 | F | Jaundice | Cystic head mass | Acinar cell Carcinoma | Well diff | – | 9 |

| 56 | F | Abdominal discomfort | Cystic head mass | IPMN/AdCa | – | pT3N1 | 8 |

| 42 | F | Abdominal pain vomiting | Chronic pancreatitis | NFET | – | – | 2 |

| 59 | F | Abdominal pain | Cystic head mass | Solid pap Cys Ca | – | – | 9 |

| 56 | M | Jaundice | Cystic head mass | IPMN/AdCa | – | pT3N1 | 6 |

All tumour sizes are in maximum dimension.

IPMN/Ad Ca, intrapapillary mucinous neoplasm with advanced adenocarcinoma; NFET, non-functioning endocrine tumour with malignant futures; Solid pap Cys Ca, solid papillary cystic carcinoma; diff, differentiation.

FALSE-POSITIVE SUBGROUP ANALYSIS

Final histology reported a benign neoplasm in 49 of 459 suspected malignant cases (10.6%; Fig. 1), including CP (n = 20) (pre-operative diagnostic work-up suggested ampullary/duodenal adenocarcinoma in 5 cases, mass/tumour in HOP in 14 cases and cholangiocarcinoma in 1 case), cystic/simple adenomas (n = 11; seven patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of ampullary/duodenum adenocarcinoma and four of mass/tumour HOP), inflammatory bile duct strictures (n = 10; pre-operative diagnosis suggested cholangiocarcinoma in five cases and mass/tumour HOP in five cases), benign ampullary disease (n = 4; pre-operative suspicion of ampullary carcinoma in one patient, cholangiocarcinoma in two and mass/tumour HOP in one) and one case each of bile duct papilloma and benign duodenal ulcer (pre-operative diagnosis was ampullary carcinoma in both), inflammatory pseudotumour and vascular malformation of the distal common bile duct (pre-operative diagnosis was mass/tumour HOP in both cases).

Figure 1.

Pre-operative diagnosis and final histology in all patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy from 1997 to 2006.

The diagnostic accuracy was 87% and sensitivity/specificity of the diagnostic workup was 97% (95% confidence interval [CI], 95.2–98.6%) and 37% (95% CI, 26.7–48.9%), respectively (positive predictive value, 89%; negative predictive value, 72%).

EUS-FNA diagnostic work-up analysis

From April 2006 and June 2008, 85 patients, with suspected benign neoplasm on the pre-operative imaging, had an EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of solid head pancreatic masses (56 were studied with ERCP also and all patients had ultra-sonography and CT scan before surgery). Fifty-five (64%) were men and 30 (36%) women. Median follow-up was 8 months (range, 1–28 months). Median age was 63 years (range, 29–81 years). The median size of the lesion was 25 mm (range, 9–170 mm). Complications occurred in four (4.7%) patients (two patients had post-procedure minor bleeding and two had abdominal discomfort). Nine (10%) patients underwent classical Whipple procedure and 76 (90%) had a pylorus preserving PD after biopsy. Sixty-two (72%) had a final histological diagnosis that confirmed the pre-operative diagnosis, 9 (11%) had different pre- and postoperative histology, 11 (13%) had no diagnostic material following EUS-FNA (uncertain group) and three (3%) had an unsuccessful procedure.

FALSE NEGATIVE

A total of 17 (20%) patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of benign pathology (8 villous adenoma, 3 IPMN, 4 chronic pancreatitis and 2 mucinous cystic tumour). The final histology confirmed the pre-operative diagnosis in 12 cases (71%) (4 patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, 3 ampullary adenomas, 3 IPMN and 2 mucinous tumours) and reported malignancy in five cases (29%); in five cases where a pre-operative diagnosis of villous adenoma was made, final histology revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (median size, 15 mm; range, 10–25 mm).

FALSE POSITIVE

Fifty-four (64%) patients had a pre-operative diagnosis of malignancy (48 adenocarcinoma, 1 hamartoma and 5 neuroendocrine tumour). The final histology confirmed the pre-operative diagnosis in 50 (93%) and reported benign neoplasm in 4 (7%). The pre-operative biopsies reported three adenocarcinoma and one neuroendocrine tumour and, at the final histology, they were found to have inflammatory changes with low/mild dysplasia and benign serous cyst adenoma, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Pre-operative diagnosis and final histology for patients who had endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration biopsy.

The diagnostic accuracy was 90% with a sensitivity and specificity of 92% (95% CI, 79.2–96.6%) and 75% (95% CI,47.4–91.6%), respectively (positive predictive value, 93%; negative predictive value, 63%; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Pre-operative diagnostic accuracy with and without EUS-FNA biopsy.

Discussion

The overall incidence of benign disease in patients who undergo PD for suspected carcinoma of head of pancreas and peri-ampullary region ranges from 10–18%. 18–21 Smith et al.22 reported a series of 603 patients who underwent PD finding benign disease in 5% and Van Gulik et al.23 reported on 220 patients with an incidence of benign disease of 6%. In 1997, the John Hopkins group published their 6-year experience of PD in 650 patients of whom 71 had chronic pancreatitis, 21 peri-ampullary adenoma and 25 cystadeno-ma with overall incidence of benign disease of 18%.24 The same group then reported a large series with an incidence of benign disease of 10.6%, finding CP in 19 patients, benign biliary tract disease in 9 patients and lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis in 11 patients.25 Kennedy et al.,26 in 2006, evaluated the incidence of chronic inflammatory disease in 162 patients who underwent PD for suspected peri-ampullary cancer, finding 21 with benign inflammatory disease (12.9%). This wide variation depends on several factors including the extent of pre-operative staging and the approach taken by the reporting pancreatobiliary surgical team to resectional surgery for benign disease. In our study, the overall incidence of benign disease was 15.6% in 499 PDs reviewed, including those on whom we performed PD for a cystic or solid mass of unknown histology, pancreatic head masses (secondary to CP) refractory to medical management or where a malignancy was suspected, inflammatory bile duct strictures and adenomas of the ampulla.

The overall 5-year survival rate was 83%, similar to series reported by Traverso (93% 5-year survival in PD for CP)27 and the Chicago group (90% survival).26 Barnes28 reported on 53 (49%) patients without peri-operative complications, the most common complication being delayed gastric emptying. We had 32 patients (41%) with peri-operative complications; none of our patients suffered delayed gastric emptying despite predominantly using the pylorus-preserving PD technique.

The analysis of the patients undergoing a PD for a pre-operative diagnosis of a benign neoplasm showed a 25% incidence of malignancy on the final histology. This suggests that, despite advances in cross sectional imaging, improvements need to be made to discriminate between benign inflammatory conditions and neoplastic disease.29 The recent use of EUS-FNA has improved diagnostic work-up and accuracy and is able to provide a cytological diagnosis in a majority of patients undergoing PD for an indeterminate pancreas head mass. The sensitivity and specificity of the procedure is 82% and 100%, respectively, with a diagnostic accuracy of 90%30 and a complication rate of approximately 5%.31 In our experience, the specificity of the diagnostic work-up following the routine introduction of EUS-FNA in 2006 is much better then without (75% vs 37%) with an acceptable complication rate (4.7%).

Although several papers report a high concordance between cytology and histological findings,32–34 there are some limitations associated with the use of cytology such as autoimmune and non-specific pancreatitis, cystic pancreatic tumours, vascular tumours and some ductal carcinomas. The EUS trucut biopsy (EUS-TCB) needle design overcomes many of the shortcomings of EUS-FNA by acquiring larger core tissue samples to allow histological examination.35 However, these techniques remain new with limited available data and seem to depend very much on personal experience.

Conclusions

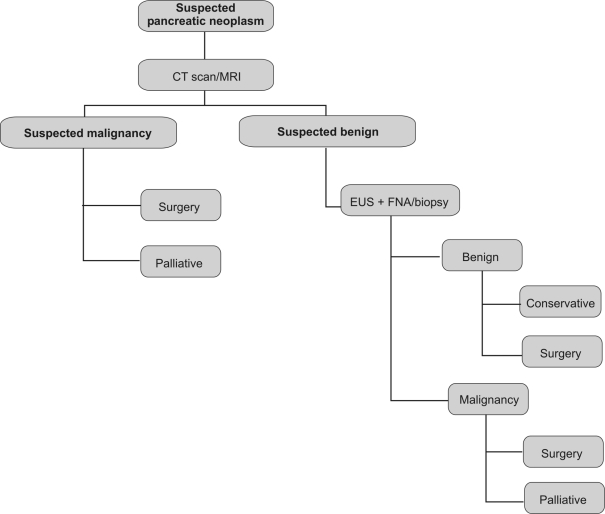

This study confirms previous reports that benign disease represents approximately 10% of PDs performed for suspected malignancy. It also demonstrates that, in a significant proportion of patients in whom PD is carried out for benign disease, there is an unsuspected underlying malignancy. Spiral CT allied to multislice technology and MRI proved advantageous in the identification of small tumours and respectability. The use of EUS-FNA is safe and improves the diagnostic work-up, reducing the discrepancy between the pre-operative diagnosis and the final histological report. The ideal, in the near future, should be to have a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, avoiding major surgery in those patients not suspected to be benign, but known to have benign disease. The retrospective analysis is the major limitation of this paper and the decision to perform a study from 1997 was done on the basis of reviewing the incidence of unexpected findings during the years and improving the diagnostic work-up. Although there has been an improvement in imaging and in the accuracy of cytology/histology, we are not yet ready to avoid surgery in all patients negative for malignant disease on EUS/ERCP cytology. It is our belief that, in view of the high incidence of false-negative diagnoses following a PD, this still remains the only option for many of these patients (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Pre-operative diagnostic algorithm.

Acknowledgments

These results were presented, in part, as an oral presentation at the Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons (AUGIS) in Cardiff, UK, in September 2007.

References

- 1.Kausch W. Das carcinoma der papilla duodeni und seine radikale Entfeinung. Beitr Z Clin Chir. 1912;78:439–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whipple AO, Parson WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg. 1935;102:763–79. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193510000-00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramhall SR, Allum WH, Jones AG, Allwood A, Cummins C, Neoptolemos JP. Incidence, treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer: an epidemiological study in the West Midlands. Br J Surg. 1995;82:111–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grace PA, Pitt HA, Tompkins RK, DenBesten L, Longmire WP., Jr Decreased mortality and morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 1986;151:141–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM, Sauter PK, Zahurak ML, et al. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticoje-junostomy following pancreaticodudodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:580–92. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199510000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron JL, Pitt JA, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Kaufman HS, Coleman J. One hun dred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomy without mortality. Ann Surg. 1993;217:430–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199305010-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varshney S, Johnson CD. Tuberculosis of the pancreas. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:564–6. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.839.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junghans R, Shumman U, Finn H, Riedel U. Foreign body granuloma of the head of pancreas caused by a fish bone; a rare differential diagnosis in the head of pancreas tumor. Chirurg. 1999;70:1489–91. doi: 10.1007/pl00002582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynaert H, Peters O, Van der Auwera J, Vanstapel MJ, Urbain D. Jaundice caused by a pancreatic mass: an exceptional presentation of Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:255–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200103000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Euscher E, Vaswani K, Frankel W. Eosinophilic pancreatitis: a rare entity that can mimic a pancreatic neoplasm. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:379–85. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2000.19371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Gulik TM, Moojen TM, van Geenen R, Rauws EA, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Differential diagnosis of focal pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 4):85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thognon P, Descottes B, Valleix D. Heterotopic pancreas: three cases. Ann Chir. 1998;52:491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urayama S, Kozarek R, Ball T, Brandabur J, Traverso L, et al. Presentation and treatment of annular pancreas in the adult population. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:995–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishizaki Y, Banday YK, Shimomura K, Shimada K, Itoh T, Idezuky Y. Localized sclerosing cholangitis in the intrapancreatic bile duct: report of case. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:294–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ectors N, Maillet B, Aerts R, Geboes K, Donner A, et al. Nonalcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1997;41:263–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang WI, Kim BJ, Lee JK, Kang P, Lee KH, et al. The clinical and radiological characteristics of focal mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis: comparison with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2009;38:401–8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31818d92c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamisawa T. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:404–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180cab67e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JS, Murayama KM, Edney JA, Rikkers LF. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for suspected but unproven malignancy. Am J Surg. 1994;169:571–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardacre JM, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Sohn TA, Abraham SC, Yeo CJ, et al. Results of pancreaticoduodenectomy for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2003;237:853–9. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000071516.54864.C1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo CF. Autoimmune sclerosing pancreatitis: the surgeon's perspective. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren KW, Choe DS, Plaza J, Relihan M. Results of radical resection for peri-ampullary cancer. Ann Surg. 1975;181:534–40. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197505000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith CD, Behrns KE, van Heerden JA, Sarr MG. Radical pancreatoduodenectomy for misdiagnosed pancreatic mass. Br J Surg. 1994;81:585–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Gulik TM, Reeders JW, Bosma A, Moojen TM, Smits NJ, et al. Incidence and clinical findings of benign inflammatory disease in patients resected for presumed pancreatic head cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticodudenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications and outcome. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00004. discussion 257–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham SC, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) in patients without malignancy: are they all ‘chronic pancreatitis’? Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:110–20. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy T, Preczewski L, Stocker SJ, Rao SM, Parsons WG, et al. Incidence of benign inflammatory disease in patients undergoing Whipple pro cedure for clinically suspected carcinoma: a single-institution experience. Am J Surg. 2006;191:437–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Traverso LW, Richard A, Kozarek RA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for chronic pan creatitis. Anatomic selection criteria and subsequent long-term outcome analysis. Ann Surg. 1997;226:429–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes SA, Lillemoe KD, Kaufman HS, Sauter PK, Yeo CJ, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign disease. Am J Surg. 1996;171:131–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80087-7. discussion 134–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasson AR, Gulizia JM, Galva A, Anderson J, Thompson J. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for suspected malignancy: have advancement in radiographic imaging improved results? Am J Surg. 2006;192:888–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeFrain C, Chang CY, Srikureja W, Nguyen PT, Gu M. Cytologic features and diagnostic pitfalls of primary ampullary tumors by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2005;105:289–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voss M, Hammel P, Molas G, Palazzo L, Dancour A, et al. Value of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses. Gut. 2000;46:244–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.2.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho JM, Darcy SJ, Eysselein VE, Venegas R, French SW, Stabile BE. Evolution of fine needle aspiration cytology in the accurate diagnosis of pancreatic neo plasms. Am Surg. 2007;73:941–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal B, Krishna NB, Labundy JL, Safdar R, Akduman EI. EUS and/or EUS-guided FNA in patients with CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging findings of enlarged pancreatic head or dilated pancreatic duct with or without a dilated common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eltoum IA, Chieng DC, Jhala D, Jhala NC, Crowe DR, et al. Cumulative sum procedure in evaluation of EUS-guided FNA cytology: the learn ing curve and diagnostic performance beyond sensitivity and specificity. Cytopathology. 2007;18:143–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy MJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided trucut biopsy of the pancreas: prospects and problems. Pancreatology. 2007;7:163–6. doi: 10.1159/000104240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber SM, Cubukcu-Dimopulo O, Palesty JA, Suriawinata A, Klimstra D, et al. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis: inflammatory mimic of pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:129–37. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00148-8. discussion 137–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shyr YM, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy justified for chronic pancreatitis masquerading as periampullary tumor? Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1163–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]