Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The aim of the study was to identify whether Trendelenburg position helps detect any further bleeding points following Valsalva manoeuvre in order to achieve adequate haemostasis in head and neck surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Fifty consecutive patients undergoing major head and neck surgical procedures were included. The protocol consisted in performing Valsalva manoeuvre to check haemostasis and treated any bleeding points identified. The operating table was tilted 30° and haemostasis was checked again and treated accordingly. The number of vessels identified and the treatment was recorded.

RESULTS

Twelve male and 38 female patients were included. The median age was 53 years and 74% had an ASA of 1. Twelve patients had complicating features such as retrosternal extensions or raised T4 levels pre-operatively. Thyroid resections were the most common operations performed. The total number of bleeding vessels identified in Trendelenburg tilt was significantly greater than when using Valsalva manoeuvre (P < 0.0001). All bleeding points found on Valsalva manoeuvre were minor (< 2 mm) and dealt with using diathermy. In Trendelenburg position, 11% of bleeding vessels required ties or stitching. The time taken during Valsalva manoeuvre was 60 s on average and 360 s in Trendelenburg position.

CONCLUSIONS

The results show that the Trendelenburg position is vastly superior to the Valsalva manoeuvre in identifying bleeding vessels at haemostasis. It has become our practice to put patients in Trendelenburg tilt routinely (we have discontinued the Valsalva manoeuvre), to check its adequacy before closing the wound. We have not noticed any intracranial complications using a tilt angle of 30°.

Keywords: Haemostatic technique, Haemostasis, Head-down tilt, Trendelenburg position, Valsalva manoeuvre

Meticulous haemostasis is important in all surgical procedures. However, the head and neck area is particularly susceptible to bleeding due to rich vascular supply in the area. It is prone to forming haematomas which might have severe consequences, such as airway compromise. Various methods have been advocated to optimise intra-operative haemostasis, which are not well documented in the current literature. These include the Valsalva manoeuvre and tilting the patient with the head down (Trendelenburg tilt), both of which may reveal occult bleeding vessels by increasing venous pressure. Another technique that is widely used is washing the wound with hydrogen peroxide in order to make bleeding points more evident.

The aim of the study was to identify whether Trendelenburg helps detect any further bleeding points following Valsalva manoeuvre in order to achieve adequate haemostasis. This is particularly important in the head and neck surgical practice by our group where we do not routinely used surgical drains.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Fifty consecutive patients undergoing major head and neck surgical procedures performed in a regional unit were included in the study. The senior author performed or supervised in all the operated cases.

Technique

After the completion of the surgical resection and performing haemostasis by standard ligation and diathermy techniques, a Valsalva manoeuvre was performed for 45 s by applying 30 cm PEEP to the ventilatory circuit. During this time, any extra bleeding points were identified and treated with diathermy, or ligatures. Following this procedure, the operating table was inclined with the head down (Trendelenburg tilt) to 50°. In this position, any further bleeding vessels were identified and treated accordingly.

Outcome

The main outcome was to identify whether Trendelenburg helps detect any further bleeding points following Valsalva manoeuvre. Secondary outcome measures were the size of the vessels identified, classified as diathermised (< 2 mm), tied or suture ligated (> 2 mm) and length of achieving haemostasis by each method. Co-morbidities and complicating features (e.g. mediastinal extension of a tumour) were recorded in case they had an adverse effect on haemostasis. Patients who had drains inserted were identified and the length of in-patient stay recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into an access database and the statistical analysis was done using SPSS (Mann–Whitney test and chi-squared used for main outcome). The project was registered with the hospital audit department.

Results

Fifty patients were included in the project, 12 males and 38 females. Two patients (one with a sternal split and one with a maxillectomy) were excluded, as they were prone to bone bleeding and the procedures were not strictly speaking in the neck. The median age was 53 years (range, 22–80 years). In the study cohort, 37 (74%) had an ASA of 1. Complicating features of the operation, such as marked neck fibrosis from Riedel's thyroiditis (in five patients) and large goitre with retrosternal extension (in four patients) were noted. In addition, three patients were thyrotoxic with TSH levels below 0.03 mIU/l (normal, 0.35–3.5 mIU/l) and two of these patients had a raised T4 level (levels, 56 and 29.8 pmol/l: normal, 11.5–22.7 pmol/l). Thyroid resections were the most common operations preformed. Table 1 shows the number and type of operations in detail.

Table 1.

Type of head and neck procedures performed

| Type of operation | Patients (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total thyroidectomy | 7 | 14 |

| Thyroid lobectomy | 23 | 46 |

| Subtotal thyroidectomy | 2 | 4 |

| Modified radical neck dissection | 5 | 10 |

| Functional neck dissection | 2 | 4 |

| Excision of lesion post triangle | 2 | 4 |

| Submandibular gland excision | 2 | 4 |

| Branchial cyst excision | 2 | 4 |

| Operations 1 & 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Superficial parotidectomy | 1 | 2 |

| Total laryngectomy | 1 | 2 |

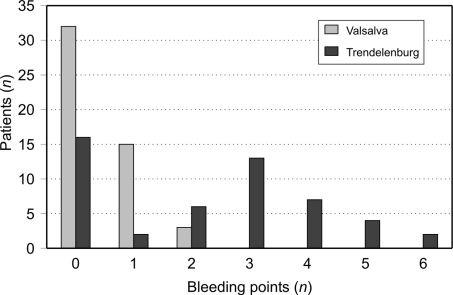

The total number of bleeding vessels identified in Trendelenburg tilt was significantly greater than when using Valsalva manoeuvre (P < 0.0001). Figure 1 shows the number of bleeding points identified in all patients using both techniques. In 32 (64%) patients, no bleeding points were identified with the Valsalva manoeuvre technique. Fifteen patients (30%) had only one visible bleeding point and in no patient were more than two bleeding points identified. Using the Trendelenburg tilt following Valsalva, further bleeding points were identifiable in 34 patients (68%).

Figure 1.

Number of bleeding points identified in patients using Valsalva and Trendelenburg position.

All bleeding points found on Valsalva manoeuvre were minor (< 2 mm) and dealt with using diathermy. In the case of head-down (Trendelenburg) position, most bleeding points were dealt with using diathermy (101/113; 89%). However, there were 12 (11%) bleeding vessels that required ties or stitching. These included the anterior jugular vein punctures when the wound filled with blood as the patient was inclined head down, and another puncture in the internal jugular vein, during a neck dissection that required stitching. Neither of these bleeding vessels was identified on Valsalva manoeuvre. The haemostasis technique used for each bleeding vessel is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Haemostasis technique used for each modality

| Technique | Bipolar diathermy | Ties |

|---|---|---|

| Valsalva (number of bleeding points) | 21 | 0 |

| Head down (number of bleeding points) | 101 | 8 |

In terms of time taken to finish haemostasis, using the Valsalva manoeuvre it took 30–60 s (median, 30 s). The limiting factor was that sustained increased positive expiratory end pressure can only be maintained for approximately 60 s maximum. In the case of head down, final haemostasis took 2–25 min (median, 6 min). There were no complications recorded for all surgical procedures.

Discussion

Good haemostasis is important in all surgery, but the risk of haematoma in the head and neck area is particularly important due to the risk of airway compromise. Recently, the use of drains in thyroid surgery has decreased considerably, as their use does not benefit the patients' outcome and may increase hospital stay.1–4 Haemostasis is, therefore, paramount whatever the method used. In our unit, we perform a large number of major head and neck procedures, most of those being thyroid cases. The senior author does not use drains for thyroid excisions, partial or total, although drains are used neck dissections.

The aim of this study was to investigate a technique which provides adequate identification of any potential bleeding vessels in achieving intra-operative haemostasis. Using the head-down position, a significantly higher number of bleeding points were identified, in comparison with Valsalva manoeuvre. The Trendelenburg technique proved more sensitive in identifying bleeding vessels that were not seen by Valsalva (113/134 bleeding vessels identified). It is worth noting that, in five cases, significant bleeding that required stitching or tying was missed using Valsalva manoeuvre. In one patient, the bleeding was from a puncture in the internal jugular vein and was missed by Valsalva technique.

It has been suggested that Valsalva manoeuvre helps in haemostasis by increasing internal jugular venous pressure and by causing reflux of venous blood.5 The limiting factor using this technique is that sustained increased positive expiratory end pressure can cause complications, such as barotrauma. Therefore, the pressure cannot be held for more than a minute limiting the chances of identifying any potential bleeding vessels.

Rex et al.6 have shown that the optimal angle of tilt for Trendelenburg is 50° as there is no further significant increase in internal jugular vein diameter with increasing angle of tilt. In the head-down technique, there is a potential risk of increased intracranial pressure and cerebral compromise; therefore, in our study, the tilt was limited to approximately 6 min.

In general terms, any vessel wider than 2–5 mm was tied or repaired with a stitch in the case of the jugular vein. Vessels with a smaller diameter were diathermised. No visible ooze was left untreated.

Conclusions

The results show that Trendelenburg tilt is vastly superior to the Valsalva manoeuvre in identifying bleeding vessels at haemostasis. It has become our practice to put patients in Trendelenburg tilt routinely (we have discontinued the Valsalva manoeuvre), to check its adequacy before closing the wound. We have not noticed any intracranial complications using a tilt angle of 30°.

References

- 1.Shandilya M, Kieran S, Walshe P, Timon C. Cervical haematoma after thyroid surgery: management and prevention. Ir Med J. 2006;99:266–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanna J, Mohil RS, Chintamani, Bhatnagar D, Mittal MK, et al. Is the routine drainage after surgery for thyroid necessary? A prospective random ized clinical study. BMC Surg. 2005;19:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SW, Lee YM, Lee JY, Kim SC, Koh YW. Is lack of placement of drains after thyroidectomy with central neck dissection safe? A prospective, randomized study. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1632–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000231314.86486.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahluwalia S, Hannan SA, Mehrzad H, Crofton M, Tolley NS. A randomised con trolled trial of routine suction drainage after elective thyroid and parathyroid surgery with ultrasound evaluation of fluid collection. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung CP, Hsu HY, Chao AC, Wong WJ, Sheng WY, Hu HH. Flow volume in the jugular vein and related hemodynamics in the branches of the jugular vein. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:500–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rex S, Brose S, Metzelder S, Hüneke R, Schälte G, et al. Prediction of fluid responsiveness in patients during cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:782–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]