Authorship and writing for the Technical Section

Authorship

There has been a trend towards increasing numbers of authors on Technical Notes and Tips: this sometimes seems excessive and unreasonable. A simple technical idea usually has one originator (or perhaps two, as a product of discussion) and it is then common to supervise a trainee in writing it up. That means that a tip or note might reasonably have two or three authors. Submissions are becoming more frequent with four or five names above them. This needs to be fully justified. I have started to write to any lead author who has more than two co-authors asking for a full explanation of the contribution of each and will do so increasingly. I advise that any submissions with more than three authors should be accompanied by a letter giving those details.

Writing

Submissions of 100 or 250 words should be perfect. Especially if they are being used to increase the experience (and CV) of trainees, senior authors should be sure that they are faultless. The shoddy presentation of some of the submissions we receive is difficult to excuse – the more so when there are a number of authors, each of whom should have read the final manuscript. Each author bears personal responsibility for its content and quality. I write some fairly blunt letters to the authors of short submissions with imperfect text and (commonly) references that are not cited in proper Vancouver style. I would like to remind all authors (not least senior ones) of their responsibilities to check that manuscripts are perfect. That ought to be easy with such short submissions.

Bruce Campbell

Editor, Technical Section

BACKGROUND

A nephrostomy tube allows maximal renal drainage where internal drainage is unachievable. Prosthetic tubes exposed to urine may calcify leading to significant difficulties in removal. A multi-modal combination of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and even open surgery have been described to remove these challenging encrusted tubes,1 in most cases requiring multiple procedures.2 We report a minimally invasive technique which has proved definitive in two such cases, thereby avoiding PCNL.

TECHNIQUE

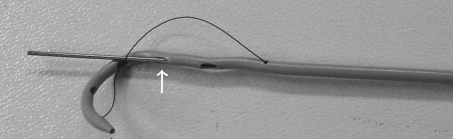

Under anaesthesia, the 1-mm lithoclast probe (fig. 1) is inserted into the lumen of the nephrostomy tube under fluoroscopic guidance. The ‘Jack-hammer’ lithoclast causes intra- and extraluminal stone to be disrupted, allowing the nephrostomy tube to uncoil and be removed without renal injury. The nephrostomy tube is pulled onto the lithoclast to prevent inadvertent progression of the lithoclast and subsequent tube fracture (fig. 2), which could potentially lead to retained fragments within the renal pelvis or tissue damage. We have used the same technique to avoid PCNL for a retained ureteric stent in a woman's transplanted kidney.

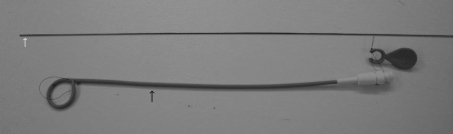

Figure 1.

The lithoclast probe (white arrow) beside the nephrostomy tube (black arrow).

Figure 2.

Intraluminal insertion of lithoclast probe into nephrostomy tube.

DISCUSSION

Removal of an encrusted stent or nephrostomy tube presents a major challenge to the urologist. This technique features once in the literature by Canby-Hagino et al.3 They describe advancing the lithoclast, which in our experience can progress out of the nephrostomy tube (fig. 3), potentially into adjacent tissue. This technique may also be considered for removing encrusted drainage. Traditionally, large seromas require multiple aspirations using a 60-ml syringe with the contents dispensed into a kidney bowl. This method can introduce infection, which is of particular significance when the seroma cavity is associated with a biomedical ureteric stents, but is probably only suitable in women where the distal coil is more readily accessible. In conclusion, this minimally invasive technique appears safe and definitive.

Figure 3.

The potential for the lithoclast probe to exit the nephrostomy tube side holes (white arrow).

References

- 1.Bultitude MF, Tiptaft RC, Glass JM, Dasgupta P. Management of encrusted ureteral stents impacted in upper tract. Urology. 2003;62:622–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam JS, Gupta M. Tips and tricks for the management of retained ureteral stents. J Endourol. 2002;16:733–41. doi: 10.1089/08927790260472881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canby-Hagino ED, Caballero RD, Harmon WJ. Intraluminal pneumatic lithotripsy for the removal of encrusted urinary catheters. J Urol. 1999;162:2058–60. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]