Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Request for Treatment (RFT) is a new approach to consent which aims to facilitate patients’ understanding of their treatment and addresses some of the flaws highlighted in a literature review of current consent practice. It aims to provide a complete clinical, medicolegal, and documentary framework for consent and places patients at the centre of their care. It also provides doctors with more robust evidence that adequate consent has been obtained, and can be implemented with ease in most clinical scenarios, especially elective surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A thorough critical analysis and literature review is undertaken looking at the current state of consent world-wide. For the first time, a complete documentary system for ‘request for treatment’ is devised including Request for Treatment forms (RFTFs) alternatively termed Patient-centred Consent Forms (PCCFs). The arguments for the legal validity and other advantages of RFT are presented.

CASE STUDY

A case with all the documentation of a full consent episode is provided which illustrates RFT in action, demonstrating the simplicity of implementation, and the robustness of the completed RFT form as a source of evidence for both consent and capacity.

CONCLUSIONS

Request for Treatment (RFT) is a request-based model for consent that facilitates patient-centred care. It has a number of advantages including unrivalled documentary evidence of consent in the patient&s own handwriting and vocabulary, demonstration of capacity, ease of implementation, and a sound legal basis. For those who may wish to use it, RFT provides a useful and novel patient-centred method of consent, and is likely to protect against negligent consent practice by highlighting patient misunderstandings early and by providing irrefutable documentary evidence that consent has been gained. It may also provide a simple method by which Gillick competence can be assessed and documented. RFT forms are available for download at www.rft.org.uk.

Keywords: Patient-centred care, Request for Treatment, Consent, Negligence

Please sign here

The complexities of consent for medical treatment can be embodied in these three words. Indeed, it is rare, but not unheard of, for these words to be the entirety of the consent process. Fortunately, they are more typically the culmination of a more extensive process - a process that is unfortunately flawed in many ways. These flaws emerge as soon as we look closely at the objectives of the consent process and the law upon which it is based.

Contradictions in law, procedural guidelines and practice are common and substantial evidence points to the fact that patients understand significantly less than we think - and that they should - about their treatment. It appears that consenting practice works more on an administrative and procedural level than on a fundamental and constructive one, and the current system does not lend itself to excellence when communicating with, and providing information for, patients. Pointing out how and why this is the case, ways in which the current system can be improved are explored and elaborated. This culminates in the proposition that consent, as it is known, could be replaced by an entirely different system altogether: a system whereby patients request treatment rather than consent to treatment, and one that puts patients at the centre of their care.

The challenge of improving a system of consent is compounded by the fact that this is a legal process as well as a clinical one. A thorough examination of the legal complexities of consent has been crucial in the development of Request for Treatment (RFT), which is based on understanding the principles of legislation and case law both in the UK and internationally, and which are touched on briefly herein.

What is the purpose of consent?

As societal values have changed, so the importance of autonomy has grown, especially in relation to medical treatment. In the last century, there has been a change from the traditional ‘doctor knows best’ model of healthcare. That approach was overtly paternalistic, and defined the doctor-patient relationship in the times before the latter half of the 20th century. In 1767, the importance of consent was acknowledged by the courts for the first time when, in the legal case of Slater v. Baker & Stapleton, surgery was performed against the wishes of the patient.1

The principle of autonomy is now so fundamental in British law that a patient of sound mind can refuse treatment even if that refusal is foolhardy and could lead to death of the patient or even that of an unborn child of a pregnant patient.2 With so much potentially at stake, it is important to have a robust process for consent not only to uphold patient autonomy and the law, but also to ensure best practice for patients and healthcare professionals.

To understand consent fully, one first needs to get to terms with its function. There are a number of benefits gained from the consent process. For the patient, these include an expression of patient autonomy per se, and this is a fundamental right of patients in a modern health service. Consent allows patients to make an informed calculation of the best course of action for themselves in the wider context of their own lives, the nuances of which are not known to doctors. The chances of successful treatment are also increased due to better co-operation. Perhaps most importantly, it provides the infrastructure for dialogue and communication between doctors and patients, and a sign of respect for patients by the medical profession. However, consent also remains a moral, ethical and professional duty as well as a legal one and, as such, provides evidence as defence against litigation in trespass and negligence.24 Poor communication is often the problem that leads to litigation; so good consenting practice is a key part of minimising this unfortunate scenario.

Upholding patient autonomy can be seen, therefore, as a philosophical and policy ideal that gains importance based upon societal values. Similarly, the importance of human rights in society grew stronger in the latter part of the 20th century and culminated in the enshrinement of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) into UK law through the Human Rights Act, 1998. Legal rulings, such as Malette v. Shulman (a life-saving blood transfusion given to a Jehovah's witness carrying a card stating their wish not to have blood was interpreted as assault) enshrined the principles of autonomy:

The judge stated:3 ‘At issue here is the freedom of the patient as an individual to exercise her right to refuse treatment and accept the consequences of her own decision.… The concepts inherent in this right are the bedrock upon which the principles of self-determination and individual autonomy are based.’

Amongst the aims of the consent process include a better understanding of the procedure and its implications and a better understanding of the risks and of any alternatives. The signing of a consent form, however, does not in itself constitute actual consent, nor provides proof that consent has been obtained - its role has been defined as mainly evidentiary:4

I regard the consent form immediately before operation as pure window dressing in this case and designed to avoid the suggestion that a patient has not been told.4

and Lord Donaldson commented in the case of Re T [1992]:

Signed consent forms will be wholly ineffective…if the patient is incapable of understanding them, they are not explained to him and or there is no good evidence (apart from a signature) that he had that understanding and fully appreciated the significance of signing it.

This specific fact is poorly recognised by many healthcare professionals; whilst written consent is good practice, the assumption that ‘the patient is not consented’ if they have not signed a consent form is false. Yet it is also important to differentiate ‘the law’ from hospital and professional guidelines and policies (e.g. General Medical Council [GMC] guidelines) to which doctors are also bound, whilst recognising the importance of each, and our duties as clinicians.

The specific legal requirements for consent are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The requirements for consent in English law

| In general, for true consent to be achieved, the patient must: |

| 1. Have capacity |

| 2. Have sufficient information |

| 3. Have understood this information |

| 4. Give consent without duress |

| As per Chatterton v. Gerson [1981] 1 All ER 257. |

The failings of consent

Cassileth and colleagues5 concluded in their paper in 1980:

[Studies] have shown that patients remain inadequately informed, even when extraordinary efforts are made to provide complete information and to ensure their understanding. This appears to be true regardless of the amount of information delivered.5

Almost 30 years on, studies continue to highlight the failings of consent: for example, in a study of 1057 audio-taped consent encounters, only 9% met the authors' definition of completeness for informed decision-making.6 In another audit of 100 consultant orthopaedic surgeons, a large proportion of consent episodes did not conform to legal or professional stipulations or guidelines.7

Indeed, ‘consent’ as a concept may also actually thwart true autonomy by enforcing the notion of patients in a passive or permissive role, rather than as equals, in the doctor–patient relationship.8

The problem of capacity

Competence is a pivotal concept in decision making about medical treatment. Competent patients' decisions about accepting or rejecting proposed treatment are respected. Incompetent patients' choices, on the other hand, are put to one side, and alternative mechanisms for deciding about their care are sought. Thus, enjoyment of one of the most fundamental rights of a free society – the right to determine what shall be done to one's body – turns on the possession of those characteristics that we view as decision-making competence.9

This eloquently sums up the importance of competence (capacity). The problem is that the evidence suggests capacity as is currently defined by law is often lacking in ‘normal’ patients:10

It is well known that many patients, despite all efforts to the contrary, remember or understand little of what they agree to during the consent process.10

It is undoubtedly the case that information overload can cause patients to ‘switch off and impede the consent process, thus hampering understanding and ‘informed’ consent. At the same time, not providing such information may be deemed negligent consenting practice. Doctors are, therefore, inherently vulnerable to a ‘Catch-22’ situation. As highlighted by a study published in The Lancet, the law, by its own stipulations regarding consent in terms of capacity, has made the attainment of valid consent impossible in a large proportion of consent episodes because capacity as defined by the law is indeed lacking in many of the patients in whom it is presumed to be present.11 Furthermore, this important fact is not generally acknowledged, and only brought to light during detailed analyses such as by Schneider and Farrell,12 who point out:

We have only scant evidence about how patients analyse what they hear and remember. But that evidence gives us good reason to doubt that their analyses meet the expectations of the bioethicists who advocate informed consent or the judges who demand it.12

The requirements of ‘informed consent’ have, therefore, been derived in the absence of the evidence which shows that these apparently reasonable stipulations are, perhaps unexpectedly, not possible.

The case for change

As with many failings in large institutions, it is often system failures rather than individual failures that are accountable. This is no more so than with the current system of consent which, through its structure, dooms the doctor-patient encounter to fail in its objectives (Table 2).

Table 2.

The failings of consent

| • The law stipulates a level of understanding from patients that decades of research have shown to be impossible to achieve consistently |

| • Consent forms are not robust documents in a court of law4 |

| • Current consent fails to pick up on patients lacking capacity11 |

| • Consent as it stands remains paternalistic by placing patients in a permissive/passive role |

| • Listing large numbers of risks to patients immediately before an operation is inhumane, counterproductive, stressful, and is rarely well-informed |

| • There is no pressure on the system to facilitate excellence in communication or information provision: constructive dialogue is often lacking |

| • The context of ‘consent’ in law, such as the age of consent (to sex) and the criminality associated with lack of consent in this context is inappropriate in the doctor–patient relationship |

| • Consent is usually a one-off episode rather than a process of recurrent interaction and mutual understanding |

This has led eminent lawyers as well as clinicians to seek alternatives:13

Doctors should surely do their best to give patients the information they want. But it is time to consider the possibility that doctors will never be able to communicate to patients all the information they need in a way that they can use effectively. It may therefore be time to chart the limits of informed consent and to consider what other approaches might help patients secure what they want and need from medicine.13

The substantial body of evidence above in addition to the ‘shop-floor’ experiences of many doctors illustrates how current consenting practice does not achieve its goals and fails both doctors and patients. It appears in particular that the consent process fails to facilitate the necessary level of communication between doctors and patients – often evidenced by the junior doctor ‘consenting’ patients just before they are taken into an anaesthetic room for surgery. Furthermore, it is illogical on a fundamental level as doctors are seeking consent in a relationship where they are not the main benefactors. Re-organising this relationship in a manner whereby patients request treatment, rather than consenting to it, provides the opportunity to alter the passive nature of the patient in the doctor-patient relationship, lessen the potential for paternalism, and put patients more ‘in the driving seat’ upholding their autonomy. It also affords patients greater responsibility with regards to their own treatment, and facilitates better communication.

Request for Treatment

Putting the patient at the centre of their care is one of the key principles of RFT. Patient-centred care is a popular buzz phrase in healthcare, but rightly so. It is about aligning the delivery of medical care with the needs and preferences of patients which can lead to superior clinical outcomes; the evidence for this is summarised in an important document entitled Educating Health Professionals to be Patient Centered produced by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (<www.iom.edu>):

Multiple studies demonstrate that meeting the aim of patient-centeredness can improve the outcomes that patients desire (Roter etal., 1995;14 Lewin etal., 2001;15 Stewart et al., 199916). Evidence demonstrates that patients who are involved with their care decisions and management have better outcomes than those who are not (Wagner et al., 2001).17 Patient self management, particularly for chronic conditions, has been shown to be associated with improvements in health status and decreased utilization of services (Lorig et al., 2001).18 Being patient-centered also has been shown to lead to greater clinician satisfaction, reduction in malpractice claims, and patient loyalty to the clinician (Meryn, 1998).19 Although a more patient-centered approach is required to deal with the health needs of the population and is associated with better health outcomes, many patients express frustration with the current reality, specifically their inability to obtain information they need, to be heard, and to have their needs met. Studies have demonstrated substantial opportunities for improvement among health professionals in understanding and communicating with patients (Laine and Davidoff, 1996;20 Meryn, 1998;19 Braddock et al., 1999;21 Stewart et al., 199916).

A request-based system of consent is aimed at re-orientating patient care in a patient-centred manner by changing the process at the very core of important decisions and actions in the doctor-patient relationship: consent.

RFT has a number of roles (Table 3). One of the key parts of RFT includes the RFT forms (RFTFs), which are in effect patient-centred consent forms.22 The process of consent currently focuses on the consent form, which provides a stable and consistent infrastructure around which to base consent. This is not unreasonable. Unfortunately, some of the negative aspects of current consent practice – such as the common occurrence of poor quality consent being obtained immediately before treatment is instigated – occur because there is no ‘fail-safe’ built into the documentation process to prevent this from happening. The infrastructure means that the patient progresses to treatment so long as the form is signed, and it is the health professional who determines the important content of the form. RFT provides an infrastructure for consent that is more stringent: one important feature of RFT is that RFTFs/PCCFs will often need to be given to patients prior to treatment, as completing them will require time and deliberation (a prerequisite for true understanding and often lacking in consent episodes). This need not be prolonged, but depends on the context of treatment and provides most benefit in an elective setting.

Table 3.

The role of RFT (patient-centred consent)

| Consent using RFT becomes: |

| • An encompassing mechanism that facilitates, promotes and establishes patient-centred care |

| • A general approach to – and replacement for – consent, focussing on a mutual process of interaction and doctor–patient communication |

| • A method of documenting consent that is more robust than traditional consent, and forms the basis of a new in-patient system |

| • A mechanism to ensure high-quality information provision to patients |

| • A mechanism to involve patients more in their own healthcare decisions |

| • A ‘soft’ method of assessing capacity |

| • A method of consent for children (parental consent) |

| • A potential method of assessment and documentation of Gillick competence for those under 16 years of age |

| • A method of protecting doctors and patients against negligent consenting practice. |

Differences between traditional consent forms and patient-centred consent forms

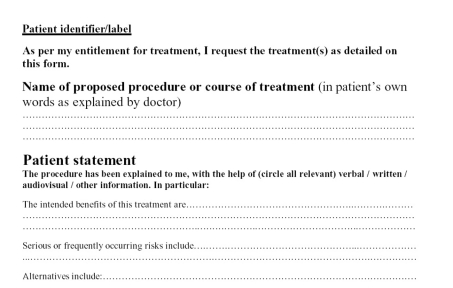

There are many similarities between RFTFs/PCCFs and existing consent forms, but the onus has changed from ‘I consent to…’ to ‘I request…’ (Fig. 1). Crucially, the majority of the text including the procedure, benefits, risks and complications, is completed by the patient, which transforms the process. This transformation is due to the much greater understanding that is required from patients to fill in sections that were previously filled in by doctors. The inevitable errors made by patients during the process are accommodated for by the provision of additional space at the end of the RFTF (Fig. 2) specifically to highlight such errors. Documentation of any errors of understanding is useful, not only to allow these to be addressed, but maybe also in any legal challenge to the validity of that consent. It also gives remarkable insights into what patients actually think about their treatment. The RFT process is complete when the clinician signs the form (Part A) – ‘I accept to undertake the treatment requested on this form’ (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Part of page 1 of the Request for Treatment Form (RFTF)/Patient-Centred Consent Form (PCCF) for completion by the patient.

Figure 2.

Page 2 of the Request for Treatment Form (Patient-Centred Consent Form, PCCF), for joint completion by the doctor and patient before treatment to deal with any errors or omissions.

Figure 3.

Final part of RFTF (PCCF) – box for doctor's signature accepting to undertake treatment. Other boxes (B and C. not shown) defer or refuse surgery for the reasons stated in those boxes.

The difference in the two approaches becomes obvious when comparing the schematics for elective surgery below. The consent process is illustrated in Figure 4, RFT in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Typical consent schematic for elective surgery.

Figure 5.

Request for Treatment schematic for elective surgery.

For elective procedures, the RFTF is given to patients at the point of information provision during the consultation process. Patients then have a considerable period of time in which to fill in the form before their admission to hospital and, during this period, have access to information materials (leaflets, DVDs, websites) and points of contact. When they are admitted, they present the form to the ‘consenting’ doctor, who will address any queries and finalise the consent process. For emergency treatment, the time-scale is reduced but the overall process remains similar.

The process of RFT has been developed to deal with many of the flaws of traditional consent highlighted earlier, without losing any important components. The documentation is more robust, in that it is in the patients' own words and writing, and importantly requires sufficient deliberation on the part of patients to ensure a properly informed process. RFT thereby ensures informed consent ‘by default’, and places patients at the centre of their treatment as equals within the doctor-patient relationship. This helps to ensure patients actually understand their treatment and risks, and goes some way towards assessing their capacity to consent. Furthermore, the process removes the notion that consent is purely a process to limit litigation, instilling more the sense of partnership between doctor and patient.

The law requires a high standard of consent practice, but does not stipulate its form – indeed even verbal consent is perfectly legitimate in law, although not necessarily best practice. RFT, therefore, remains within the remit of current legislation, and can be used without legal obstacle, as it not only accomplishes the objectives of written consent, but does so to a high standard of evidence for the reasons argued above – evidence being the main purpose of written consent. Moreover, it continuously guides clinicians to improve their communication skills through feedback, as, at every consent episode, their ability to make patients understand is clearly evident from what patients write on the form.

The famous Gillick case23 led to the concept of Gillick competence, where a child can give valid consent if they are deemed sufficiently mature and possess an appropriate level of understanding. Until now, there has been no established method of undertaking the actual assessment of Gillick competence, or documenting that assessment. Request for Treatment may well provide an avenue for the simultaneous assessment of Gillick competence (the ability to successfully complete the RFT process) as well as documenting that assessment via the RFTF and this is an area for future development and investigation.

In general, the implementation of RFT is straightforward since it fits into current legal and clinical frameworks.

RFT in action: example case

A 42-year-old patient was referred by her GP requesting breast reduction. She was otherwise fit and well and there were no contra-indications to surgery and she was an appropriate surgical candidate. When she attended the pre-assessment clinic 2 weeks prior to surgery, she was provided with a Request for Treatment form and the process of RFT and consent explained to her. The details, risks and complications of surgery as discussed in the out-patient clinic were re-iterated and an RFT form provided to her for completion before she was admitted to hospital. The section she completed is reproduced in Figure 6. The text of the content is transcribed below.

Figure 6.

The patient not the doctor completes the majority of the consent form.

The entry in the patients' own words and handwriting provides fascinating insights into her understanding of her proposed treatment and into the consent process. It also illustrates the robustness of the completed form in demonstrating the completeness (or lack) of understanding of the patient on specific points. For example, under ‘benefits’, she specifies: ‘no more neck ache, no more back ache…able to do sports without discomfort’. Under serious or frequently occurring risks, she specifies: ‘nipple loss, infections and blood transfusions’. It is significant that she has not acknowledged the significant additional risks of the procedure imparted to her during two consultations and contained in the information leaflet provided to her. Again, this illustrates how powerful the RFT process is in demonstrating the level of patient knowledge and completeness of consent. The additional risks of the procedure that were not originally acknowledged by the patient are then re-iterated to the patient and documented on the ‘clarification of treatment details’ section which is completed by the doctor -these additions included: deep vein thrombosis, and implications for future breast feeding amongst others (Fig. 7). The form is then signed by the doctor: ‘I agree to undertake the treatment requested on this form’.

Figure 7.

After the patient has completed the request form, errors, misperceptions and misunderstanding are usually revealed. The ‘clarification of treatment details’ section is completed by the doctor and signed by the patient to correct any such errors or omissions and provide evidence of the evolving and interactive nature of the consent episode. The form is then signed by the doctor: ‘I agree to undertake the treatment requested on this form’.

Conclusions

Consent as the law requires has, in practical terms, not been consistently achieved in medical practice for as long as the concept of consent has itself existed. The same questions regarding the failures of consent are being asked now as were being asked decades ago. It is without question that patients retain and understand very little regarding their treatment despite best efforts, and there appears to be a discrepancy between the understanding of this fact by the medical profession and by the courts, which do not seem to appreciate the extent of this problem.

As argued above, Request for Treatment provides a complete, simple, legally valid and practically implementable system for achieving consent, underpinned by medicolegal analysis. Importantly, RFT ensures good communication between doctors and patients through increased dialogue, good information provision, and transparent documentation. Those enthusiastic to implement RFT will need to develop excellent patient information resources; indeed, the ability to implement RFT for elective surgery should be a testament to a service's standard of communication and information provision. As the new framework becomes more familiar, the concepts and processes can be expanded to cover almost any clinical scenario.

The aim is for RFT to be non-prescriptive, and to be tailored individually to practices, hospitals or even specific operations or procedures. Dual-consent using RFT alongside current practise will be a likely starting point for most. It is hoped that this strategy can help improve consenting practice within the UK and beyond for those who may wish to use it.

Request for Treatment forms (patient-centred consent forms) are freely available for download for non-profit use at <www.rft.org.uk>.

References

- 1.Slater v. Baker & Stapleton. 95 Eng. 860, 2 Wils. KB 359 (1767)

- 2. St George's Healthcare NHS Trust v S [1998] 3 All ER 673.

- 3. JA Robins in Malette v Shulman (1990) 67 DLR (4th) 321 (Ont Canada) [PubMed]

- 4. J Popwell in Taylor v Shropshire HA [1998] Lloyds LR: Medical 395 p 398.

- 5.Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Informed consent – why are its goals imperfectly realised? N Engl J Med. 1980;302:896. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004173021605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice. JAMA. 1999;282:2313–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S, Mayahi R. Consent in orthopaedic surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:339–41. doi: 10.1308/147870804353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habiba M, Jackson C, Akkad A, Kenyon S, Dixon-Woods M. Women's accounts of consenting to surgery: is consent a quality problem? Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:422–7. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Miller DS, Hurwitz S. Attitudes towards clinical trials among patients and the public. JAMA. 1982;248:968–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raymont V, Bingley W, Buchanan A, David AS, Hayward P, et al. Prevalence of mental incapacity in medical inpatients and associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2004;364:1421–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider CE, Farrell MH. Law and medicine. In: Freeman M, Lewis A, editors. Current Legal Issues. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider CE. The Practice of Autonomy: Patients, Doctors, and Medical Decisions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians' interviewing skills and reducing patients' emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-manage ment program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meryn S. Improving communication skills: to carry coals to…. Med Teach. 1998;20:331–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine. A professional evolution. JAMA. 1996;275:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braddock 3rd CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282:2313–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. < www.rft.org.uk.>.

- 23. Gillick v. West Norfolk and Wisbech Area HA [1985] 3 All ER 402. [PubMed]

- 24.Shokrollahi K. Consent and other medicolegal issues. In: Leaper D, Whitaker IS, editors. Oxford Handbook of Postoperative Complications. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 451–462. ch.24. [Google Scholar]