Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Failure rates of laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) vary from 2–30%. A degree of anatomical failure is common, and the most common failure is intrathoracic wrap herniation. We have assessed anatomical integrity of the crural repair and wrap using marking Liga clips placed at the time of surgery and compared this with symptomatic outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A prospective study was undertaken on 50 patients who underwent LARS in a single centre over a 3-year period. Each had an X-ray on the first postoperative day and a barium swallow at 6 months at which the distance was measured between the marking Liga clips. An increase in interclip distance of > 25–49% was deemed ‘mild separation’, and an increase of > 50% ‘moderate separation’. Patients completed a standardised symptom questionnaire at 6 months.

RESULTS

At 6 months' postoperatively, 22% had mild separation of the crural repair with a mean Visick score of 1.18, and 54% had moderate separation with a mean Visick score of 1.26. Mild separation of the wrap occurred in 28% with a mean Visick score of 1.21 and 22% moderate separation with a mean Visick score of 1.18. Three percent had mild separation of both the crural repair and wrap with a mean Visick score of 1.0, and 16% moderate separation with a mean Visick score of 1.13. Of patients, 14% had evidence of some degree of failure on barium swallow but only one of these was significant intrathoracic migration of the wrap which was symptomatic and required re-do surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of some form of anatomical failure, as determined by an increase in the interclip distance, is high at 6 months' postoperatively following LARS. However, this does not seem to correlate with a subjective recurrence of symptoms.

Keywords: Laparoscopic antireflux surgery, LARS, Intrathoracic wrap herniation, Anatomical failure

Correction of the physiological factors contributing to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is only possible by surgical fundoplication and, since the advent of laparoscopic fundoplication by Dallemagne et al. in 1991,1 is an increasingly attractive option for patients due to low morbidity and greatly reduced length of hospital stay. As a result, laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) has become the gold standard in the surgical treatment of GORD. Lundell et al.2 reported a 7-year follow-up comparing results in patients randomised to proton-pump inhibition or open antireflux surgery, and surgery was shown to be more effective at controlling overall disease symptoms, but post-fundoplication complaints were problematic.

Failure rates of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication vary from 2% to 30%,3–7 depending on the definition of ‘failure’. Both patients and clinicians may interpret resumption of medical treatment as failure, but the majority of patients taking antireflux medication are taking it for atypical or non-reflux related symptoms.7–9 An anatomical explanation for failed reflux surgery can often be found, such as breakdown of the fundoplication, an over-tight wrap, intrathoracic herniation of the wrap or telescoping of the lower oesophageal sphincter through the wrap.10–12 In a series of 307 re-do fundoplications, Smith et al.6 found that fundoplication herniation was the most common mechanism of failure. Symptomatic patients with objective evidence of failure of LARS can be offered re-do surgery: several studies have demonstrated that this can be safely undertaken laparoscopically.6,13–16 Donkervoort et al.17 studied anatomical wrap position and the outcome following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and, 2 years' postoperatively, found that the anatomical repair failed in 27% using ‘strict’ criteria and 55% using ‘less strict’ criteria, although there was no demonstrable influence on subjective outcome.

Our study, examined the relationship between the anatomical integrity of both wrap and crural repair, using Liga clips placed at the time of surgery, with postoperative symptoms to investigate further the postoperative outcome in patients with GORD.

Patients and Methods

Fifty patients (27 males, 23 females) aged 22–72 years (median, 47 years) were included in this prospective study, recruited from a single centre from March 2004 until November 2007. All patients undergoing LARS at a single hospital were included in the study. A further 18 patients with incomplete postoperative data (imaging or symptom scores) were excluded from the study.

Pre-operative evaluation included structured symptom questionnaire, endoscopy, 24-h pH monitoring and oesophageal manometry studies as described previously.8

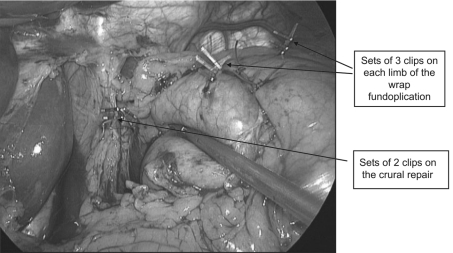

All patients underwent standardised laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for GORD, performed by two experienced laparoscopic upper GI surgeons. The operative technique has been described in detail previously.8 Three Liga clips were sited on a single suture on each limb of the wrap, and two Liga clips on each arm of the crural repair (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Intra-operative photograph illustrating the positionin the clips.

On the first postoperative day, all patients underwent an anteroposterior X-ray coned to the diaphragmatic hiatus on arrested inspiration (dose 65.9 cGy/cm2), to identify the marking clips and hence confirm the anatomical position of the wrap and crural repair. At 6 months' postoperatively, patients underwent a barium swallow to verify anatomical position of the wrap and integrity of the crural repair. All radiographs were reviewed and reported by a single radiologist (RR) who was blinded to symptomatic outcome of the surgery. A single author (ND), blinded to the symptom scores at the time of data collection, measured the distance between the clips on both the focused hiatal X-ray and barium swallow (Fig. 2). An increase in inter-clip distance (ICD) of < 24% was deemed to be an ‘intact’ repair. Anatomical failure at 6 months' postoperatively was described as an increase in the inter-clip distance of > 25–49% for ‘mild separation’, or > 50% for ‘moderate separation’ by comparison to the first postoperative day imaging. These percentages were chosen arbitrarily since there may be some lateral movement artefact of the clips.

Figure 2.

X-ray showing inter-clip distance measurement for the wrap on the left, and the inter-clip distance measurement of the crural repair on the right.

Patients completed a standardised symptom questionnaire at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months following surgery, and gave their Visick score. These data were collected by gastrointestinal physiology nurses.

The relationship between anatomical failure and symptomatic outcome (using the Visick score) was analysed using the Mann–Whitney test, with P < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Results

All 50 patients were deemed to have satisfactory positioning of the Liga clips on the X-ray taken on the first postoperative day.

At day 1 postoperatively, the mean inter-clip distance for the crural repair was 8.4 mm (range, 4–22 mm) and for the wrap 26.2 mm (range, 10–63 mm).

At 6 months' postoperatively, the mean inter-clip distance for the crural repair was 11.4 mm (range, 5–22 mm) and for the wrap 31 mm (range, 14–50 mm).

Six months' postoperatively, 11 patients (22%) had mild separation of the crural repair, and 27 patients (54%) had moderate separation. Similarly, 14 patients (28%) had mild separation of the wrap, and 11 (22%) had moderate separation. Three patients (6%) had mild separation of both the crural repair and the wrap, compared with 8 patients (16%) with moderate separation.

The mean 6-month Visick score for patients who had an anatomically intact crural repair was 1.17, and for an intact wrap was 1.24; those patients who had both an anatomically intact crural repair and wrap had a mean 6-month Visick score of 1.22 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The relationship between the status of the crural repair and Visick score at 6 months' postoperatively

| Crural repair | Visick Score | Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Median | Range | Mann–Whitney test | |

| Intact | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Intact vs mild P = 0.925 |

| Mild separation | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Intact vs moderate P = 0.532 |

| Moderate separation | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Mild vs moderate P = 0.615 |

The mean 6-month Visick score for patients with mild separation of the crural repair was 1.18 compared with 1.26 for moderate separation (Table 1).

The mean 6-month Visick score for patients with mild separation of the wrap was 1.21 compared with 1.18 for moderate separation (Table 2).

Table 2.

The relationship between the status of the wrap and Visick score 6 months' postoperatively

| Wrap | Visick Score | Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Median | Range | Mann–Whitney test | |

| Intact | 19 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Intact vs mild P = 0.857 |

| Mild separation | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Intact vs moderate P = 0.703 |

| Moderate separation | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1–2 | Mild vs moderate P = 0.844 |

Those who had mild separation of both the crural repair and the wrap had a mean 6-month Visick score of 1.0; those with moderate separation had a mean 6-month Visick score of 1.13 (Table 3).

Table 3.

The relationship of anatomical failure of both the crural repair and the wrap to Visick score at 6 months' postoperatively

| Crural repair and wrap failure | Visick score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Mild separation | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate separation | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

There was no significant difference between the status of the crural repair or wrap, and the 6-month Visick score (Tables 1 and 2).

Visick scores measured at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months following surgery remained the same in 78% of patients, and in 12% Visick scores improved over time. The remaining 10% of patients reported deterioration in Visick score over time and of these 60% had moderate separation of the crural repair with an intact wrap.

At 6 months' postoperatively, eight patients (16%) were taking anti-acid medication: six were taking proton-pump inhibitors – one for gastroprotection due to concurrent medication for arthritis, one for symptoms of reflux, and the remaining four for other indications. One patient took an H2 blocker for 1 month only, and one patient took the occasional Rennie.

On barium swallow at 6 months' postoperatively, seven patients (14%) had radiological evidence of some degree of anatomical failure in addition to some degree of increase in clip distance, but only one patient was symptomatic. The symptomatic patient had complained of feeling something ’moving’ at his 6-month follow-up, and intrathoracic herniation of the stomach was seen on barium swallow. He underwent laparoscopic re-do surgery at 8 months' postoperatively, at which time the wrap was found to have herniated due to disruption of the crural repair. The wrap inter-clip measurement had increased with moderate clip separation but, interestingly, the crural repair clip distances remained static. The Visick score in this patient was 1.

Discussion

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) has been shown to be a safe and effective treatment for GORD. The most common reason for failure is intrathoracic migration of the wrap, leading to recurrent GORD symptoms.11 A review of 104 failed antireflux operations by Iqbal et al.13 showed that 50% of patients had disruption of the crural closure and 35% had partial disruption of the fundoplication.

A successful outcome from LARS is dependent on individual patient's expectations. We employ the Visick score to represent patients' satisfaction with the procedure since it is a well-validated and reproducible scoring system. The success of the surgery can be assessed objectively with barium swallow, endoscopy, pH monitoring and manometry. We have used barium swallow as our routine follow-up investigation, since it affords the necessary information at a reasonable cost and is considerably more acceptable to the patient than other methods such as pH monitoring and/or endoscopy. The use of ICD measurement is a new means of identifying wrap herniation and possible separation/attenuation of crural and or wrap repair. We have used the radiological identification of normal clip position and ICD to re-assure patients. Ours is the first study to use this method.

Our study had shown that the prevalence is high of some form of anatomical failure at 6 months following LARS, with 54% of patients having moderate separation of the crural repair and 22% of patients having moderate separation of the wrap. We have reported the individual findings for wrap separation, crural separation and combined separation since this is what we and others have found at the time of re-do surgery.18 What our study has shown, however, is that objective evidence of anatomical failure does not appear to correlate with subjective recurrence of symptoms. This finding is in agreement with that from Donkervoort et al.,17 who also reported that the repair did not stand the test of time anatomically in 55% of patients but with no demonstrable influence on subjective outcome. It is possible that the proportional increase in interclip distance (25% and 50%) may be too rigorous owing to the possible lie of the wrap marker clips, although similar variation in lie is not possible for the crural clips. This is further supported by the fact that only one patient had a major wrap herniation confirmed on barium swallow. Both the wrap and crural repair interclip distances measured on day 1 postoperatively show considerable variation; this may be because some wraps are more bulky than others, thus the sutures lie further apart. In some patients sutures for the clips may have been placed more laterally than in others and, finally, although the sutures lie vertically at laparoscopy (Fig. 1), on desufflation each wrap suture may take on a more lateral or rotated lie, thus increasing the interclip distance.

Donkervoort et al.17 undertook barium swallows at 2 years' postoperatively as part of their follow-up, which is a commendable time period. We have noticed a progressive reduction in the number of patients willing to attend follow-up appointments (18 patients in this study). To date, no further patients have returned with symptoms requiring investigation but it is likely that some of these patients would have experienced anatomical failure. Indeed, it is surprising that crural failure and wrap herniation is not more common considering the exceptionally high pressure exerted on the diaphragm during activities such as coughing, sneezing and forced expiration against a closed glottis during lifting and straining. In the absence of hiatal hernia, when no crural repair was undertaken, Watson et al.19 reported an unacceptably high rate of post-LARS wrap herniation.

Wrap herniation has been to shown to be the most common mechanism of failure in LARS, as a result of failure of the crural repair, and some centres recommend the use of a prosthetic mesh to reinforce the crural repair. Granderath et al.20 compared simple sutured crural closure with simple sutured cruroplasty and onlay of a polypropylene mesh. Eight percent of the mesh patients had intrathoracic wrap migration by comparison with 26% in the simple sutured group. Prosthetic mesh reinforcement has been shown to increase the incidence of early postoperative dysphagia: this, however, commonly resolves so that, at 1-year postoperatively, the dysphagia rates are comparable with those of simple sutured crural repair.21 We reserve this technique for those with significant hiatal defects.

A small percentage of patients undergoing LARS will be dissatisfied with the outcome of surgery despite no objective evidence of anatomical failure. Previous studies have assessed the ability to predict poor outcome. Velanovich22 employed quality of life measurements to predict patient satisfaction outcomes following LARS: he found that 34 of 290 patients who were dissatisfied postoperatively had statistically significant worse scores pre-operatively and less symptomatic improvement.

Patient satisfaction with LARS is generally high and can be maintained in the long-term.7,8,17 The present study demonstrates that, even though there may be evidence of anatomical failure, the symptomatic outcome following LARS remains successful.

References

- 1.Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:138–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Hatlebakk JG, Wallin L, et al. Seven-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial comparing proton-pump inhibition with surgical therapy for reflux oesophagitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:198–203. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson GG, Watson DI, Britten-Jones R, Mitchell PC, Anvari M. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg. 1994;220:137–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199408000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuschieri A, Hunter JG, Wolfe B, Swanstrom LL, Hutson W. Multicentre prospective evaluation of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc. 1995;7:505–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00316690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinder RA, Filipi CJ, Wetscher G, Neary P, DeMeester TR, Perdikis G. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is an effective treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 1994;220:472–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199410000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CD, McClusky DA, Rajad MA, Lederman AB, Hunter JG. When fundopli cation fails redo? Ann Surg. 2005;241:861–71. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000165198.29398.4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Delattre JF, Meyer C, Baulieux J, Mosnier H. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: five-year results and beyond in 1340 patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:946–51. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth MI, Jones L, Stratford J, Dehn TCB. Results of laparoscopic Nissen fun doplication at 2–8 years after surgery. Br J Surg. 2002;89:476–81. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2002.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonatti H, Bammer T, Achem ST, Lukens F, DeVault KR, et al. Use of acid suppression medications after laparoscopic antireflux surgery: prevalence and clinical indications. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:267–72. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Hanrahan T, Marples M, Bancewicz J. Recurrent reflux and wrap disruption after Nissen fundoplication: detection, incidence and timing. Br J Surg. 1990;77:545–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein HJ, Feussner H, Siewert JR. Failure of antireflux surgery: causes and management strategies. Am J Surg. 1996;171:36–40. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soper NJ, Dunnegan D. Anatomical fundoplication failure after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg. 1999;229:669–77. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iqbal A, Awad Z, Simkins J, Shah R, Haider M, et al. Repair of 104 failed anti-reflux operations. Ann Surg. 2006;244:42–51. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217627.59289.eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne J, Smithers B, Nathanson LK, Martin I, Ong HS, Gotley DC. Symptomatic and functional outcome after laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux sur gery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:996–1001. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khajanchee YS, O'Rourke R, Cassera MA, Gatta P, Hansen PD, Swanström LL. Laparoscopic reintervention for failed antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 2007;142:785–92. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safranek PM, Gifford CJ, Booth MI, Dehn TC. Results of laparoscopic reopera tion for failed antireflux surgery: does the indication for redo surgery affect the outcome? Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:341–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donkervoort SC, Bais JE, Rijnhart-de Jong H, Gooszen HG. Impact of anatomi cal wrap position on the outcome of Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2003;90:854–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb PJ, Myers JC, Jamieson GG, Thompson SK, Devitt PG, Watson DI. Long-term outcomes of revisional surgery following laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2009;96:391–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Mitchell PC, Game PA. Paraoesophageal hiatus hernia: an important complication of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. BrJ Surg. 1995;82:521–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granderath FA, Schweiger UM, Kamolz T, Asche KU, Pointner R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with prosthetic hiatal closure reduces postoperative intrathoracic wrap herniation. Arch Surg. 2005;140:40–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pointner R. Impact of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with prosthetic hiatal closure on esophageal body motility. Arch Surg. 2006;141:625–32. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.7.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velanovich V. Using quality-of-life measurements to predict patient satisfaction outcomes for antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 2004;139:621–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]