Abstract

N2-Alkyl analogues of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (OG) were synthesized (alkyl = propyl, benzyl) via reductive amination of the protected OG nucleoside and incorporated into various positions of an RNA strand. Thermal stability studies of duplexes containing A or C opposite a single modified base revealed only moderate destabilization. Both OG as well as its N2-alkyl analogues can pair opposite A or C with nearly equal stability, potentially offering a new means of modulating RNA-protein interactions in the minor vs. major grooves.

Chemical modification of nucleosides has been a successful strategy for antiviral,1 antimetabolite,2 antitumor,3,4 and diagnostic agents.4 Modified nucleosides in oligomers exist naturally due to cellular reactions on both the bases and the sugars of DNA and RNA and have also been introduced into oligomers synthetically. Modified nucleosides are common in the RNA field due to applications in investigating reaction mechanisms,5,6 imparting favorable properties on siRNAs,7,8 probing RNA structure and function,9–11 and exploring interactions between RNA and proteins or small molecules.1

Both sugar and backbone modifications have been explored to improve nuclease stability and target identification in antisense and siRNA approaches;12,13 however, examples of base modification in these applications are few by comparison.14–16 The ability to alter the hydrophobicity and steric properties of the major and minor groove appeared to us as a possible means of modulating both interstrand interactions as well as nucleic acid-protein interactions7,17,18 thereby expanding the range of nucleic acid modifications in the design of DNA and RNA therapeutics.

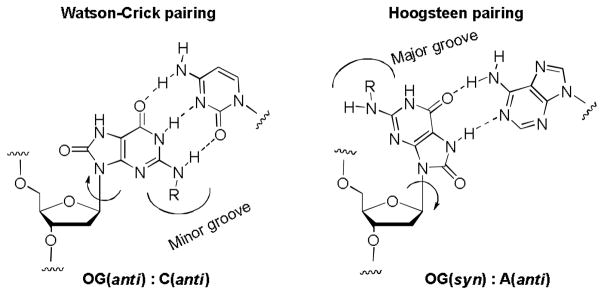

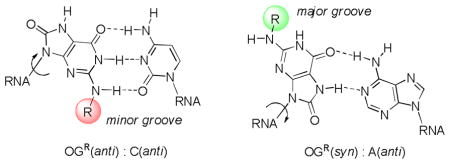

Inspiration for the present work came from one of the major products of oxidative damage to the DNA, namely 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (OG).19–21 Introduction of an oxo group at C8 of the purine increases the propensity of the purine to flip from the normal anti conformation to syn, where it exposes the Hoogsteen face of the purine to base pairing. Like its parent guanine, OG(anti) accepts cytosine as a Watson-Crick partner, while the complementary base for OG(syn) is adenosine (Figure 1). During the anti-syn conformational change, the N2-amino group and the C8-oxo groups exchange positions between the minor and major grooves (Figure 1). As a result, addition of an alkyl or aryl group to the exocyclic amine should enable the placement of the substituent in either groove, in a way that will be governed by the identity of the base opposite.

Figure 1.

8-Oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (OG) pairing with A and C.

OG can be synthetically incorporated into DNA and RNA oligomers via the corresponding phosphoramidite. While we, among others, have been studying OG and its incorporation into oligomers, including chemical characterization and enzymology with DNA processing enzymes,22,23 OG is rarely studied in RNA. Thermal denaturation studies,22,24,25 NMR studies,26 and x-ray crystallographic structures23,27,28 of the OG(syn):A(anti) base pair show that the B-form DNA helix is only very slightly perturbed by the presence of this non-canonical pair. Because the DNA-RNA duplex synthesized during transcription is A-form, the transcription studies suggest that both the Watson-Crick OG(anti):C(anti) and the OG(syn):A(anti) base pairs can be stably accommodated in A-form RNA.29,30

In the G:C or OG:C Watson-Crick base pair, only one hydrogen on the N2 nitrogen of the purine is involved in hydrogen-bonding to the opposite base; the other hydrogen projects into the minor groove. In the OG:A base pair, the entire exocyclic amino group of OG projects into the major groove. Thus, replacement of one of the hydrogens of OG’s N2 group by an alkyl should have a very minimal effect on the hydrogen bonding ability in a duplex. However, the presence of a bulky substituent could have other effects on local solvation or steric interactions that are not easily predicted. Therefore our current focus was to study the effects of different substitutions that vary in steric bulk at the N2 position of OG on the stability of duplex formation in RNA. Chemical modifications in siRNA are an important wayto address issues such as stability, delivery and reducing off-target effects.14,31,32 The ability of OG to base pair in two alternative conformations, syn and anti, could play a major role in siRNA therapeutics. The switching of steric bulk between minor (OG(anti)) vs. major (OG(syn)) grooves may prevent undesirable interactions depending on pairing with C or A, respectively, in the complementary strand.

In previous work, we reported the stability of OG and its oxidation products in DNA strands.22 The Beal laboratory has shown that chemical modification of Gs in caspase-2 siRNAs can reduce their ability to bind to off-target proteins such as Protein Kinase R (PKR) while maintaining caspase-2 gene knockdown capability.33 Hence, in our current experiments, we have synthesized various N2-alkyl derivatives of OG phosphoramidites and incorporated them into a caspase-2 siRNA sequence by replacing selected uracils with the modified OGs. The caspase-2 sequence selected has Us situated near the 5′ end, near the 3′ end and in the middle of the guide strand sequence. Accordingly, we chose positions 4 (5′ seed region), 11 (middle; at the Argonaute2 cleavage site) and 16 (near the 3′ terminus) for incorporation of modified bases (vide infra). These three positions would allow us to understand the effects of the modified nucleosides on stability of RNA duplexes in detail. Furthermore, by forming the RNA duplex with either A or C opposite modified guanosines, we could evaluate the duplex stability with both Watson-Crick (OG:C) and Hoogsteen (OG:A) base pairs in these three regions. The 2′-deoxynucleoside of OG was selected for study because the absence of the 2′-OH group might readily facilitate both the syn and anti conformations in comparison to the ribonucleoside analogue.30 Previous studies have shown that the presence of a few 2′-deoxynucleosides in an RNA strand does not dramatically alter its physical or biological properties.14 In the current work, the N2 substituents are propyl or benzyl in comparison to H in order to evaluate a small vs. medium-sized hydrophobic group added to either the major or minor groove.

Initially, attempts were made to follow a synthetic scheme similar to that of alkyl-substituted 2-aminopurines by substitution of the diacylated-2-bromo-2′-deoxyinosine nucleoside.17 Unfortunately, substitution of 2-bromoinosine with ethyl, propyl and benzyl amine all proceeded in low yields. Furthermore, diazotization of deoxyguanosine to yield the 2-bromo-2′-deoxyinosine base led to many different products as in previous work.34,35

As a second approach, we attempted reductive amination of aldehydes with guanosine; reaction of 2′-deoxyguanosine with the respective aldehyde in the presence of NaBH3CN led to a ~60% yield along with a small amount of dialkylated side product (~20%). However, subsequent conversion into 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine yielded many side products complicating the purification.

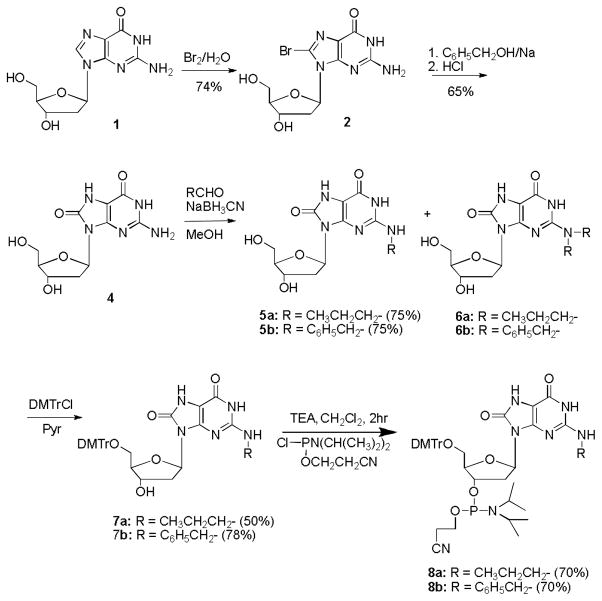

Thus, the most promising procedure was to install the 8-oxo moiety first and then carry out reductive amination to prepare the N2-alkyl derivatives of OG; these were then finally converted into the corresponding phosphoramidites.49 The overall procedure, shown in Scheme I, involved conversion of 8-bromo-2′-deoxyguanosine (2) to 8-O-benzyl-2′-deoxyguanosine (3) in the presence of sodium benzylate and DMSO. Compound 3 is highly unstable in acidic conditions and yields OG (4) upon stirring with 1 M HCl for 2 hours. Reductive amination of OG in the presence of sodium cyanoborohydride in 20% aqueous methanol and the appropriate aldehyde yielded the respective N2-alkylated products (5) in good yield. Modest changes in the the concentration of NaBH3CN or the aldehyde did not alter the yield of the mono-alkylated or di-alkylated products (5 vs. 6) significantly; however, a large excess of the aldehyde and longer reaction times yielded predominately the dialkylated compound. The mono-N2-alkylated product was purified chromatographically, and the 5′-OH was protected by DMTrCl in pyridine to yield (7). This compound was then converted into its phosphoramidite (8) using triethylamine as base in CH2Cl2 under anhydrous conditions.36 The modified phosphoramidites were introduced at either one, two or three positions via standard solid-phase synthesis. Coupling efficiencies for the modified phosphoramidites were similar to those of unmodified bases. The deprotected oligonucleotides were purified by ion-exchange chromatography, analyzed by negative ion ESI-MS, and hybridized to form RNA duplexes.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of N2-alkyl-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine phosphoramidites

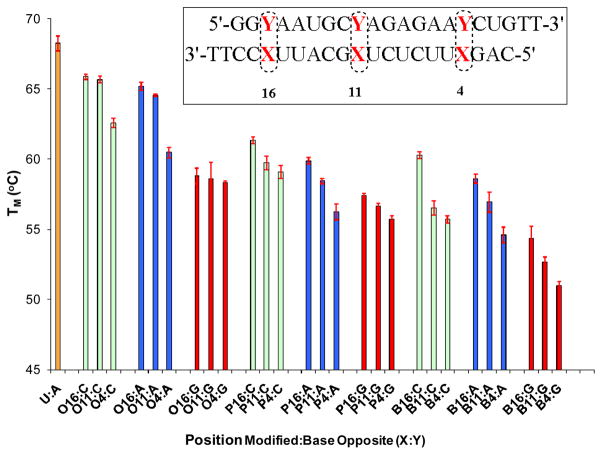

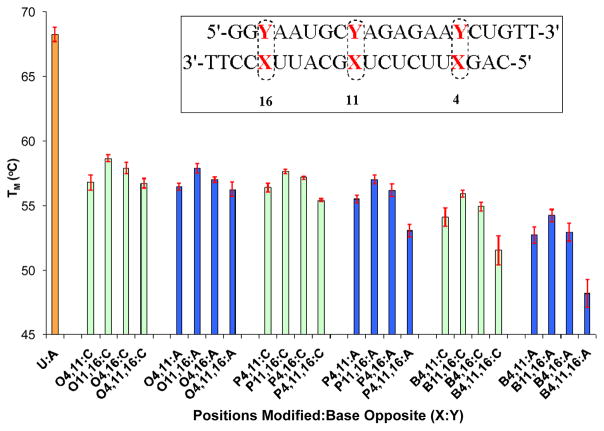

The effect of the 2′deoxy-OG nucleosides with and without N2-alkyl substituents on duplex stability was investigated via thermal denaturation (TM) studies at pH 7.4 in 100 mM NaCl. In the initial set of experiments, the nucleoside analogs were incorporated into the duplex at each of three different positions (4, 11 or 16) of the guide strand sequence from caspase 2 with C, A and G in the strand opposite (Figure 2). The modified strands containing OG and its analogues were also compared with the unmodified strand containing a U:A base pair. In the second set of experiments, the nucleoside analogs were incorporated into the duplex at more than one position, i.e. (4,11), (11,16), (4,16) or (4,11,16) of the antisense strands opposite A or C (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

TM values of RNA duplexes singly modified at positions 4, 11 or 16 of the caspase-2 guide sequence compared to native U:A base pairs in these positions. The passenger strand has either Y = C (green bars), A (blue bars) or G (red bars) opposite the modified site X, in which the R group on N2 of OG is H (X = O), propyl (X = P), or benzyl (X = B).

Figure 3.

TM values of RNA duplexes doubly and triply modified at positions 4, 11 and/or 16 of the caspase-2 guide sequence compared to native U:A base pairs in these positions. The passenger strand has either Y = C (green bars) or A (blue bars) opposite the modified site X, in which the R group on N2 of OG is H (X = O), propyl (X = P), or benzyl (X = B).

TM measurements showed that replacement of a single U:A base pair with a single O:C (O = OG with R=H) at positions 16 or 11 decreased the TM by ~ 2°C whereas at position 4 it decreased by 5 °C. Indeed, position 4 proved to be consistently more sensitive to the effects of modified bases. Introduction of O:A at the same positions showed a further slight decrease in TM of ~1°C. However, on introduction of guanosine opposite the modified bases, which is expected to be a destabilizing mispair, the TM decreased considerably (ΔTm ~ 8°C). In DNA, the OG(syn):G(anti) base pair can form, but is somewhat less stable,37 therefore it was of interest to know the likelihood of mispairing with G if OG was present in the guide strand of an siRNA.

Introduction of alkyl substituents onto the N2 position of OG, either propyl (P) and benzyl (B), showed similar TM patterns, of which the benzyl modification was somewhat more destabilizing than the propyl analogue or OG itself. In brief, the order of stability of these duplex oligonucleotides can be listed as: Unmodified > O > P > B. From the pattern observed from the data, it was clear that the larger the N2 group, the greater the destabilizing effect, although all duplexes with single modifications were still quite stable (TM ~60°C). The small difference in TM between the pairing against A and C further supports the concept that OG can switch conformations according to the complementary base, projecting the N2 substituent into either the major or minor groove. Interference with RNA-protein contacts at these sites is expected to disrupt complexes with double-stranded RNA binding motifs in key proteins.

In the next set of experiments (Figure 3), the alkylated OGs were incorporated into the duplex at 2 or 3 positions of the caspase-2 guide strand sequence with either As or Cs in the strand opposite. As expected, this decreased the stability even further with most of the TM values of strands having modifications at more than one position being around 55°C. These strands still form stable duplexes, however, and the differences in TM values between pairing against A or C remained very similar.

In conclusion, we have developed an optimized route to N2-alkyl derivatives of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′deoxyguanosine phosphoramidites and incorporated them into the caspase-2 siRNA guide sequence at one, two or three positions in which a U site was replaced by an OG nucleotide. The thermal stabilities of duplexes containing OG(anti):C(anti) vs. OG(syn):A(anti) were consistent with the conclusion that OG can exist in either the syn or anti orientation depending on the identity of the base opposite. Introduction of alkyl groups onto the exocyclic amino group led to only modest decreases in stability. No major sequence effects were evident although modification at position 4, a 5′GXU-3′ sequence context, led to slightly greater destabilizing effects than at positions 11 (5′-UXG-3′) or 16 (5′-UXC-3′). The overall stabilities of the duplexes and the small differences in stabilities of N2-alkyl-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine on pairing with A and C suggests that these modifications can be successfully incorporated into siRNA duplexes with a view to switching between modes that might prevent unwanted protein interactions while permitting silencing activity.

Experimental Section

N2-Propyl-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (5a)

To a suspension of 4,3,31 (950 mg, 3.3 mmol) and NaBH3CN (628 mg, 9.9 mmol) in methanol (80 mL) was added propanal (8.16 mL, 114 mmol) in one portion, and the mixture was heated at 50oC overnight under nitrogen. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column chromatography using 20% MeOH-CH2Cl2 to yield 805 mg (75%) of 5a. 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO): δ10.4-9.9 (2 H, bs), 6.95 (1 H, bs), 6.03 (l H, t, J = 6.04 Hz), 5.17 (1 H, bs), 5.7 (1 H, bs), 4.36-4.30 (1H, m), 4.31-4.27 (1 H, m), 3.58-3.47 (1H, m), 3.65-3.52 (2 H), 3.42- 3.31 (1 H, m), 3.04-2.76 (1H, m), 1.88-1.88 (1 H, m), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz) 13C NMR ((CD3)2SO): δ 151.7, 146.9, 124.2, 98.5, 94.2, 87.1, 80.7, 71.2, 64.1, 62.4, 42.2, 35.6, 22.1, 11.3 ESI-MS (m/z): Calcd for C13H19N5O5Na (M+Na+) 348.1284; Found 348.1286.

5′-O-4,4′-Dimethoxytrityl-N2-propyl-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (7a)

To a solution of 5a (400 mg, 1.23 mmol) in dry pyridine (6 mL) cooled in ice water was added 4,4′-DMTrCl (500 mg, 1.47 mmol). The cooling bath was removed and stirring was continued at RT for 15 min, followed by cooling in ice and quenching with water (50 mL). The solution was extracted with CH2C12 (5 × 20 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with H2O (2 × 20 mL) and then dried over MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude residue was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using MeOH-CH2Cl2 containing 2% triethylamine to inhibit detritylation yielding 7a (385 mg, 50%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 10.22 (2 H), 7.50-6.89 (13 H, m), 6.41(1H, bs), 6.21 (l H, t, J = 6.05Hz), 4.55-4.51 (l H, m), 4.01-3.98 (l H, m), 3.88- 3.80 (1 H, m], 3.86 and 3.85 (6 H, 2 s), 3.57 -3.30 (2 H, 2 m), 3.18 -3.06 (2 H, m), 2.23-2.19 (2 H, m), 1.50-1.43 (2 H, m), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz); 13CNMR (CD2Cl2): δ 176.4, 154.5, 152.4, 147.6, 140.6, 128.9, 128.8, 127.7, 127.5, 127.3, 99.5, 87.6, 81.4, 71.9, 63.0, 44.4, 43.4, 36.0, 25.3, ESI-MS (m/z): Calcd for C34H37N5O7 Na (M+Na+) 650.2591; Found 650.2604.

3′-O-[(Diisopropylamino)-(2-cyanoethoxy)phosphino]-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-N2-propyl-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8a)

To a mixture of 7a (0.112 g, 0.18 mmol) dried over P2O5 in a vacuum desiccator for 24–48 h and then co-evaporated with 1:1 dry CH2Cl2 and benzene prior to reaction, plus dry Et3N (0.044 g, 0.43 mmol) in dry CH2C12 (1 mL) under N2 was added 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropyl-phosphoramidochloridite (0.050 g, 0.25 mmol). The reaction was monitored by TLC analysis for 20 min; the solvent was evaporated, and a mixture of dry THF-benzene (1:4; 25 mL) was introduced, stirred for 10 min and filtered under N2 to remove the Et3N•HCl. The process was then repeated twice using dry benzene as the solvent. The material was purified by column chromatography using 5% MeOH-CH2Cl2 containing 2% triethylamine. The resultant viscous foamy material, when dried over P2O5 in a vacuum desiccator at RT overnight, led to a yield of 105 mg of 8a (70%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): 7.42-6.74 (13 H, m), 6.25 (l H, t, J = 6.05 Hz), 4.72 (l H, m), 4.21-4.08 (2 H, m), 3.79 (6H, s), 3.59-3.52 (4 H, m,), 3.42- 3.14 (2 H, m), 3.12-3.01 (4H, m), 2.75-2.70 (2 H, m), 2.40-2.23 (2 H, m), 1.48- 1.05 (14 H, m), 0.85, (3H, t, J = 7.5). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 158.8, 152.9, 149.2, 147.9, 136.3, 130.3, 128.5, 128.4, 127.9, 126.9, 113.2, 98.6, 86.2, 81.3, 64.2, 58.6, 55.6, 55.4, 45.5, 43.3, 24.6, 22.6, 20.7, 11.6. 31PNMR (CD2Cl2): 147.69, 147.27 ESI-MS (m/z): calcd for C43H54N7O8PNa (M+Na+) 850.3669; Found 850.3662.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. P. A. Beal (UC, Davis) for valuable comments and the NIH for financial support (GM080784).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE. Additional experimental procedures, copies of 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectra for new nucleoside derivatives, sequence information, Tm curves and mass spectral data for oligomers. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Duong A, Mousa SA. Drugs Today (Barc) 2009;45:751–761. doi: 10.1358/dot.2009.45.10.1427441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foss FM. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2004;17:573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordheim LP, Dumontet C. Biochim Biophys Acta, Rev Cancer. 2007;1776:138–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ, Mariani G. Q J Nucl Med. 1996;40:301–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maydanovych O, Easterwood LM, Cui T, Veliz EA, Pokharel S, Beal PA. Methods Enzymol. 2007;424:369–386. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)24017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suydam IT, Strobel SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13639–13648. doi: 10.1021/ja803336y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrazas M, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:346–353. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watts JK, Deleavey GF, Damha MJ. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rist MJ, Marino JP. Curr Org Chem. 2002;6:775–793. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hougland JL, Piccirilli JA. Methods Enzymol. 2009;468:107–125. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)68006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2579–2619. doi: 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla S, Sumaria CS, Pradeepkumar PI. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:328–349. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozners E. Curr Org Chem. 2006;10:675–692. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu YL, Rana TM. RNA. 2003;9:1034–1048. doi: 10.1261/rna.5103703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somoza A, Silverman A, Miller R, Chelliserrykattil J, Kool E. Chemistry Euro J. 2008;14:7978–7987. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia J, Noronha A, Toudjarska I, Li F, Akinc A, Braich R, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Rajeev KG, Egli M, Manoharan M. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:176–183. doi: 10.1021/cb600063p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peacock H, Fostvedt E, Beal PA. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5 doi: 10.1021/cb100245u. ASAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Xu J, Karimiahmadabadi M, Zhou C, Chattopadhyaya J. J Org Chem. 2010;75:7112–7128. doi: 10.1021/jo101207d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood ML, Esteve A, Morningstar ML, Kuziemko GM, Essigmann JM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6023–6032. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Kreutzer DA, Essigmann JM. Mutat Res, Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 1998;400:99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burrows CJ, Muller JG, Kornyushyna O, Luo W, Duarte V, Leipold MD, David SS. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):713–717. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krahn JM, Beard WA, Miller H, Grollman AP, Wilson SH. Structure. 2003;11:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00930-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ober M, Mueller H, Pieck C, Gierlich J, Carell T. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18143–18149. doi: 10.1021/ja0549188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamm ML, Billig K. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:4068–4070. doi: 10.1039/b612597b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kouchakdjian M, Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Eisenberg M, Johnson F, Grollman AP, Patel DJ. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1403–1412. doi: 10.1021/bi00219a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brieba LG, Eichman BF, Kokoska RJ, Doublie S, Kunkel TA, Ellenberger T. EMBO J. 2004;23:3452–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu GW, Ober M, Carell T, Beese LS. Nature. 2004;431:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature02908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SK, Lee SH, Kwon OS, Moon BJ. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;37:657–662. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2004.37.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SK, Yokoyama S, Takaku H, Moon BJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:939–944. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiu Y-L, Ali A, Chu C-y, Cao H, Rana TM. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiu YL, Rana TM. Mol Cell. 2002;10:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puthenveetil S, Whitby L, Ren J, Kelnar K, Krebs JF, Beal PA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4900–4911. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki T, Yamaoka R, Nishi M, Ide H, Makino K. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2515–2516. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glaser R, Rayat S, Lewis M, Son MS, Meyer S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6108–6119. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Johnson F. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:608–617. doi: 10.1021/tx00029a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiviyanathan V, Somasunderam A, Hazra TK, Mitra S, Gorenstein DG. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:433–442. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.