Abstract

Incidence and rate of cardiovascular disease differ between men and women across the life span. Although hypertension is more prominent in men than women, there is a group of vasomotor disorders [i.e. Raynaud’s disease, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) of menopause and migraine] with a female predominance. Both sex and hormones interact to modulate neuroeffector mechanisms including integrated regulation of the Sry gene and direct effect of sex steroid hormones on synthesis, release and disposition of monoamine neurotransmitters, and distribution and sensitivity of their receptors in brain areas associated with autonomic control. The interaction of the sex chromosomes and steroids also modulates these effector tissues, that is, the heart, vascular smooth muscle and endothelium. While involvement of central serotonergic centers has been studied in regard to mood disorders such as depression, their contribution to cardiovascular risk is gaining attention. Studies are needed to further evaluate how hormonal treatments and drugs used to modulate adrenergic and serotonergic activity affect progression and risk for cardiovascular disease in men and women.

Keywords: adrenergic, baroreflex, estrogen, female, male, norepinephrine, parasympathetic, sympathetic, vasospasm

Introduction

Sex differences in cardiovascular function are well documented and it is generally considered that women are at reduced risk and rate for adverse cardiovascular events compared to men of similar age and health status. These differences diminish for women at menopause when estrogen levels decrease [43]. Altered activation of the autonomic nervous system contributes to some cardiovascular disease, the most prominent of which is hypertension. While hypertension is more frequent and occurs at earlier ages in men compared to women, there are a group of vasomotor syndromes which show a female predominance. These disorders include Raynaud’s disease, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) of menopause and migraine. However, unlike hypertension, the underlying mechanisms contributing to these disorders are poorly understood and few studies have evaluated the basis for the sex disparity in presentation.

Sex steroid hormones directly modulate vascular function through regulation of endothelium-derived factors and regulation of intracellular calcium and calcium-sensitivity of the vascular smooth muscle [18, 50, 58]. The goal of this brief review is to present and evaluate evidence for the role of sex steroids on autonomic control of vasomotor function, with a primary focus on mechanisms involving estrogen. Evidence will be presented in the context of integrated physiology including the spectrum of in vitro studies, in vivo animal preparations and studies conducted in conscious humans. Influences of sex steroids on neuroeffector junction, in terms of both peripheral vascular and central neuronal responses will be discussed in order to link regulation of blood pressure to overall vasomotor function. Hormonal modulation of neuronal nitric oxide and cholinergic mechanisms of vasodilatation as related to erectile function and dysfunction are outside the scope of the present review. However, the interested reader is referred to several reviews focusing on these important topics [61, 69, 77, 78].

Peripheral sympathetic neuroeffector mechanisms

Vascular smooth muscle is innervated by efferent autonomic neurons, which form the primary mechanism for the regulation of vascular tone in the resistance arteriole network. This innervation in humans is primarily by sympathetic neurons where there is little evidence for efferent cholinergic innervation of the peripheral resistance arterioles [62] (with the exception of the nitrergic neurons which innervate the vasculature of the penile arteries [77]). Consequently, alterations in sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerve activity and the transduction of this activity into vasomotor tone have significant effects on the regulation of blood flow and arterial pressure. In young men, the resting activity of sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerves is positively related to total peripheral vascular resistance. Interestingly, this relationship is not present in young women [11, 31], suggesting that sex or sex hormones might influence peripheral sympathetic neuroeffector mechanisms in humans.

In humans, cutaneous circulation of the head, limbs and trunk is controlled by two types of sympathetic neurons: adrenergic neurons control cutaneous vasoconstriction and cholinergic neurons control vasodilatation [40]. Skin blood flow changes during the menstrual cycle in women suggesting that female sex steroids modulate sensitivity and responses of these circuits [8, 10]. The relationship of hormonal modulation of these pathways as related to vasomotor symptoms of menopause has not been investigated. The absence of research in this area may reflect the lack of appropriate animal models as sympathetic cholinergic neurons are unique to humans.

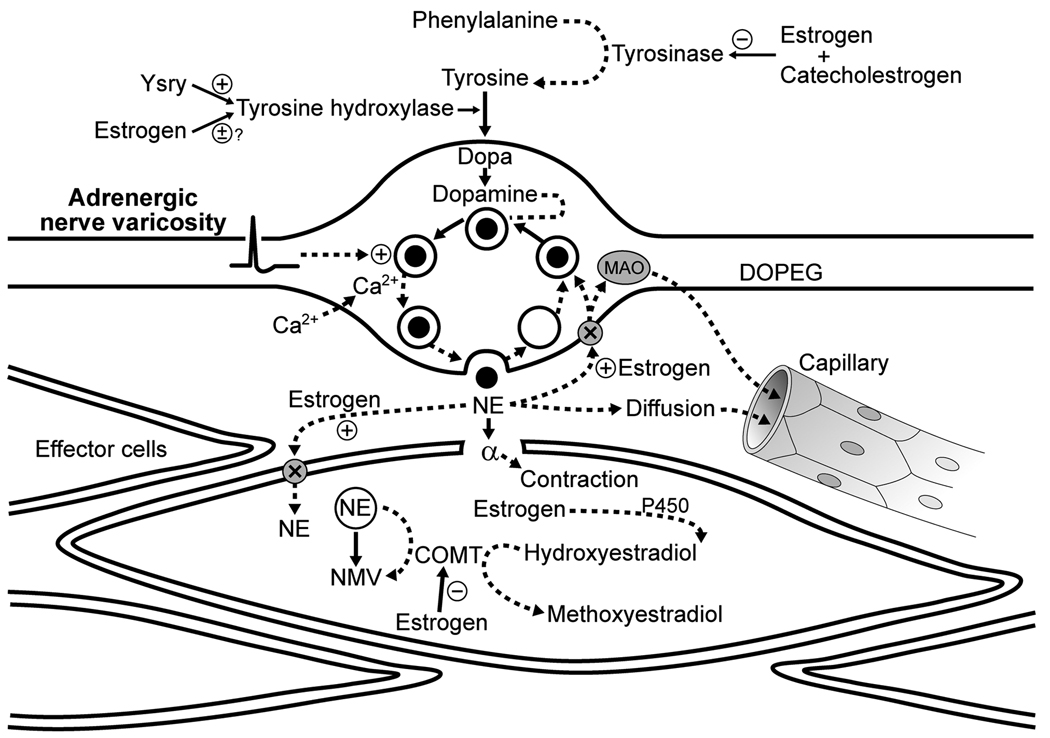

At the postganglionic sympathetic adrenergic neuroeffector junction there are several sites where sex hormones could influence the transduction of nerve activity into changes in vascular smooth muscle tone (Figure 1): a) the synthesis and release of the main neurotransmitter, norepinephrine, b) re-uptake and degradation of norepinephrine, and c) post-junctional activation of adrenergic receptors on the smooth muscle. These same target sites for hormone action would also influence sympathetic cholinergic transmission although there are no data available on this topic. Therefore, only effects of sex steroids on sympathetic adrenergic neurotransmission will be discussed in detail.

Figure 1.

Schematic of potential influence of sex and estrogen on synthesis and disposition of norepinephrine from the peripheral adrenergic nerve terminal. Norepinephrine is synthesized from a series of enzymatic steps which are modulated by estrogen and catecholestrogens. Gene products of Sry modulate tyrosine hydroxylase which provides a male gene linkage to control of sympathetic transmitter. Estrogen and metabolites also increase uptake of norepinephrine into the terminal but decrease degradation through inhibition of catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT). Other abbreviations: Ca2+, calcium; DOPEG, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NE, norepinephrine; NMV, normetanephrine;. P450, cytochrome P450; +, activation; −, inhibition; X, transporter.

Sex and norepinephrine synthesis

Tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme for norepinephrine synthesis within the sympathetic synapse (Figure 1), is regulated by the Sry locus on the Y chromosome [19, 53, 80]. Transfection of a Y chromosome from a hypertensive male animal into a normotensive male resulted in hypertension while the reverse procedure, transfection of the Y chromosome from a normotensive male into a hypertensive animal, reduced blood pressure [55]. Thus, this locus contributes to development of hypertension in male animals. Furthermore, transfection of Sry into the adrenal medulla of normotensive male rats increased tyrosine hydroxylase activity concomitant with elevated systolic blood pressure and plasma catecholamines [19]. Transfection of the Sry1 locus into the kidney of normotensive male animals also increased blood pressure, resting plasma concentrations of norepinephrine, renal tyrosine hydroxylase, and the pressor response to air stress [20]. Thus, increased tyrosine hydroxylase activity in males due to Sry expression may partially explain why men are more at risk for developing hypertension compared to women of the same age [9, 85].

The Sry gene is also required for the development of the testes. Removal of the testes decreases development of some forms of hypertension in experimental animals [36] suggesting that testosterone may contribute to development of hypertension in males. In order to dissociate effects of the gonadal hormones from those of the sex chromosomes, an animal model has been developed in which the Sry gene is deleted from the Y chromosome resulting in an XY animal without testes. When the Sry gene is inserted into an autosome of an XX animal, testes develop. These manipulations result in what is called 4 core genotype: XX and XY−Sry animals with ovaries and XXSry and XY animals with testes [4]. Although baseline blood pressure was not different among groups, removal of the gonads resulted in a greater increase in blood pressure in XX and XXSry animals compared to XY and XY−Sry animals suggesting that regulation of enzymes other than tyrosine hydroxylase (although this was not measured in the study) may contribute to sex differences in development of hypertension and that the X chromosome may contribute to hypertension associated with the renin/angiotensin system [36].

Whether female gonadal hormones modulate tyrosine hydroxylase activity is controversial. In the superior cervical ganglia of female rats, levels of tyrosine hydroxylase were higher in cervical ganglia from female rats during proestrus compared to ovariectomized females; moreover, cervical ganglia from pregnant rats had a higher tyrosine hydroxylase level compared to those from normally cycling females. Despite the effect of female reproductive status on expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, the level of this enzyme in the ganglia was not correlated with levels of circulating progesterone or estradiol [2]. Conversely, chronic administration of 17β-estradiol alone actually decreased tyrosine hydroxylase levels in the superior sympathetic ganglia of ovariectomized female rats [39]. Differing results between studies might be explained by a possible antagonising effect of progesterone. Moreover, these studies did not control for different levels of sympathetic nerve activity which occur in differing hormonal states, thus, altered expression of tyrosine hydroxylase protein may be explained by changes in sympathetic nerve activity induced by the central effects of the hormones (see section Central neuroeffector mechanisms and baroreflex) and not by any direct effects of the gonadal hormones on expression or activity of the enzyme.

Formation of norepinephrine also depends on tyrosinase activity (which forms the substrate for norepinephrine synthesis; tyrosine). Tyrosinase activity appears to be inhibited by 17β-estradiol and its metabolic by-products, the catecholestrogens. The catecholestrogens, 2- and 4-hydroxylestradiol, are formed by hydroxylation of estradiol by several enzymes, the most prominent being a cytochrome P-450-dependant monooxygenase [6, 60]. Thus, 17β-estradiol could limit the production of norepinephrine indirectly by decreasing the amount of substrate (tyrosine). Indeed, plasma levels of tyrosine decreased in male to female transsexuals treated with estrogens plus anti-androgen but increased in female to male transsexuals treated with testosterone [28]. In addition, catecholestrogens directly inhibit tyrosine hydroxylase activity. Thus hormonal regulation of the adrenergic transmitter occurs at several points in the synthetic pathway (Figure 1 [44]). Thus, gonadal steroids also regulate synthesis of adrenergic transmitter independent of the X or Y chromosome complement.

Sex and norepinephrine release, re-uptake and degradation

Release of norepinephrine from the nerve terminal is inhibited by activation of alpha2-adrenergic receptors (as well as other receptor activated processes) on the nerve terminal [56]. Little is known regarding how gonadal hormones or sex modulates the distribution of the various receptor subtypes on the synaptic terminal and if their regulation would parallel the expression of the same receptor subtype on the post-synaptic neuron or tissue. However, superfusion of 17β-estradiol onto isolated segments of canine saphenous veins increased the concentration of norepinephrine in the overflow superfusate during electrical stimulation [30]. Since estradiol may inhibit enzymes involved in norepinephrine synthesis, increased concentrations of norepinephrine in the superfusate when estradiol is superfused is perplexing. Consequently, those authors concluded that the augmented concentration of norepinephrine was likely due to changes in the degradation of the neurotransmitter perhaps due to inhibition of either neuronal or extraneuronal uptake of the transmitter in the presence of estradiol [30].

At the neuroeffector junction there are several mechanisms for neurotransmitter disposition: neuronal re-uptake, non-neuronal re-uptake and degradation and removal of the neurotransmitter via the capillary network (Figure 1). Transmembrane neurotransmitter sodium symporter (NSS) transporters function to remove transmitter from the synaptic cleft by uptake of norepinephrine, as well as serotonin and dopamine, into the nerve terminals [83]. Activity of these transporters, especially the norepinephrine transporter (NET), may regulate sympathetic signals at the heart, blood vessels and kidney [46]. Inhibition of the transporter with reboxetine augmented the heart rate response to an orthostatic challenge to a greater extent in men than women [71]. The authors of that study conclude that the contribution of NET activity in the heart may not be as great in women as in men. However, systemic inhibition may affect central components of sympathetic activation because, inhibition of NET resulted in the same attenuation of responses to a cold pressor test in men and women [71].

Alterations in transporter activity by female sex steroids may be organ specific. For example, inhibiting the transporter resulted in a greater increase in blood pressure during the follicular than luteal phase of the menstrual cycle but heart rate and cardiac output increased to a greater extent in the luteal compared to follicular phase [52]. Changes in the activity of NET transporter are implicated in orthostatic intolerance including POTS which occurs more frequently in young women than young men and may be associated with a coding mutation of the NET gene [25].

Evidence also suggests that estradiol and the catecholestrogens affect norepinephrine disposition via non-neuronal degradation in the vascular smooth muscle [6, 50]. The enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) in the vascular smooth muscle degrades norepinephrine to normetanephrine. Additionally, this enzyme also metabolizes the catecholestrogens to methyloxyestrogens [6, 17]. Thus, the catecholestrogens appear to competitively bind to COMT and inhibit the methylation of catecholamines in the liver [5, 7], in canine adrenergic nerve endings [30] and the rat heart [16]. Consequently, when catecholestrogens are high, the concentration of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft may increase, with the net effect of prolonging the impact of an adrenergic neuronal signal on both pre- and post-junctional adrenergic receptors [6] and perhaps increasing the amount of norepinephrine which can be removed by the capillaries. In this context, plasma levels of norepinephrine are greater during the luteal phase (estrogen and progesterone high) compared to the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle in young healthy women [51]. Given the multiple points of potential modulation of estradiol and its metabolites on synthesis, uptake, neuronal degradation and spill over, measures of norepinephrine in the plasma may not always correlate with sympathetic nerve activity in women. More work is needed to identify possible genetic variance in enzymes associated with estrogen metabolism and their relationship in women with vasomotor syndromes [14, 72].

Sex and post-junctional activation of adrenergic receptors

How then do these various actions of estrogen on synthesis, uptake, and degradation of norepinephrine affect vasoconstrictor responses to sympathetic nerve activity? Premenopausal women have either a similar or blunted vasoconstrictor response to efferent adrenergic stimuli compared to men [34]; whereas, postmenopausal women appear to become more responsive to adrenergic stimuli [59]. In addition, as mentioned earlier, sympathetic nerve activity is not related to the resistance of the peripheral vessels in women as it is in young men [11, 31]. One additional factor contributing to these sex differences is the distribution and sensitivity of post-junctional adrenergic receptors (Figure 1). Estrogen administration to male rats enhanced α-adrenergic mediated vasoconstrictor responses of the mesenteric arteries [12]. These studies in gonadally intact male animals are in contrast to studies in female animals which demonstrate a blunted vasoconstrictor response to norepinephrine infusion following estrogen treatment of ovariectomized female rats [86] and perimenopausal women [74]. The influence of the female sex hormones on the adrenergic receptors can further be emphasized by evidence which shows that young women appear to have an attenuated forearm vasoconstrictor response to norepinephrine infusion during the luteal phase (high estradiol) vs. the early follicular phase (low estradiol) of their menstrual cycle [24]. Distribution and sensitivity of alpha adrenergic receptors on digital arteries are implicated in the etiology of Raynaud’s disease [13]. Adrenergic activation of the cerebral blood vessels is also implicated in migraine (see [50]).

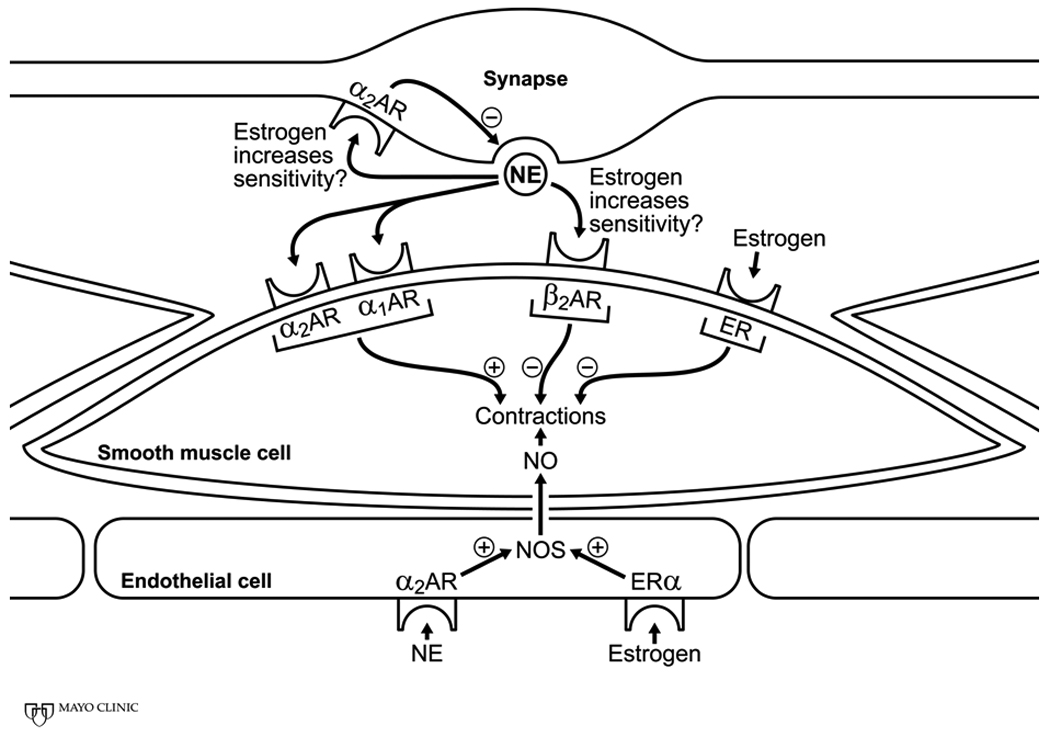

The vasoconstrictor response to α-adrenergic stimulation may also be blunted in women compared to men because of direct actions of estrogen on the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle. These effects express as a functional antagonism of the sympathetic activation [45, 49, 75, 81] (Figure 2). For example, circulating norepinephrine may stimulate release of nitric oxide from the vascular endothelium through activation of alpha2 adrenergic receptors on these cells [3]. Estrogen increases transcription of nitric oxide synthase which increases the amount of available enzyme in these cells (see [18, 50]). Also, estrogen binds to membrane estrogen receptors stimulating release of nitric oxide from the endothelium [18]. Tonic release of nitric oxide would oppose vasoconstrictor effects of sympathetic stimulation. Activation of estrogen receptors on (in) the smooth muscle reduces calcium influx, facilitates calcium efflux and reduces the calcium sensitivity of the contractile elements [42]. In addition, 2-methoxyestradiol, (the metabolic by-product of estradiol, after methylation by COMT) may also increase basal production of nitric oxide from both endothelial and smooth muscle cells[17, 22]. COMT and 2-methoxyestradiol are low in women with severe pre-eclampsia and could serve as targets to prevent pre-eclampsia in pregnant women [37].

Figure 2.

Schematic of potential sites through which estrogen modulates sympathetic neuronal activation of vascular smooth muscle contraction. Estrogen may increase the sensitivity of both alpha and beta adrenergic receptors which depending upon the distribution of these receptors in specific arterial beds would increase or decrease arterial tone. These increases or decreases in arterial tone could result from direct estrogen receptor mediated regulation of intracellular calcium and calcium sensitivity of the contractile elements or indirect modulation of contraction through release of nitric oxide from the endothelium or modulation of pre-synaptic inhibition. Abbreviations: AR, adrenergic receptors; ER, estrogen receptor; NE, norepinephrine; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; +, activation; −, inhibition.

There appears to be a pseudo-decrease in α-adrenergic receptor sensitivity when estrogen is present in the arterial network which may reflect increased β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity [23]. In ovariectomized female rats, estrogen treatment increased β2-adrenergic receptor mediated vasodilator response to isoproterenol. Thus, concurrent β-adrenergic vasodilator activity via norepinephrine stimulation may offset α-adrenergic mediated vasoconstriction in young women. In this context, the β2-adrenergic receptors on the vascular smooth muscle are more sensitive in young women vs. men of a similar age [41]. In humans, vasoconstrictor responses of the brachial artery to infusions of norepinephrine are enhanced by concurrent administration of β-blockers in women, but not in young men [41], supporting the observations in rats that estrogen increases the affinity or the number of β-adrenergic receptors for catecholamines.

Central neuroeffector mechanisms and baroreflex

The autonomic nervous system is essential for regulating heart rate and arterial pressure via the arterial baroreflex. The activity of the autonomic nerves is controlled centrally via nuclei which relay excitatory or inhibitory information to the pre-ganglionic autonomic fibers in the sympathetic and/or parasympathetic pathways. Sex hormones directly affect the activity of these pathways, thus altering peripheral sympathetic and parasympathetic neural activity, and subsequently, cardiovascular function.

Central estrogen receptors

Since multiple central neurons express estrogen receptors [1, 29], estrogen directly influences the central transduction of neuronal messages to the autonomic ganglia [63, 64]. Acute intra-venous administration of 17β-estradiol increases parasympathetic nerve activity in female and male rats [64, 65], whereas, decreases in renal sympathetic nerve activity appears only in female rats [68]. These effects were blocked by injection of an estrogen receptor antagonist either into the nucleus ambiguous [65] or the intrathecal space of the spinal cord [64], suggesting that the peripheral effects were mediated centrally.

The direct action of 17β-estradiol on the central nuclei depends on the brain area exposed to the hormone. For example, 17β-estradiol injected into the central nucleus of the amygdala decreased sympathetic nerve activity, but 17β-estradiol injected into the lateral hypothalamic area increased sympathetic nerve activity [67]. Estrogen receptor α appears to be the most prominent estrogen receptor subtype in the brain, however, estrogen receptor β has also been identified [29]. The distribution of these receptors throughout the central nuclei might account for some of the differential sympathetic effects of central estrogen administration [73]. Peripheral vasodilatation associated with vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes/flushes) of menopause is most likely centrally mediated through estrogenic modulation of hypothalamic regions associated with temperature regulation. Although estrogen treatment reduces the severity and frequency of these periodic episodes, insight into the mechanisms and regulatory pathways involved remains to be clarified as investigative work is hampered by the lack of a robust animal model to study this phenomenon. The contribution of sympathetic cholinergic fibers in expression of hot flashes remains to be explored.

Whether or not vasomotor instability in post-menopausal women confers cardiovascular risk is unclear. Vasomotor symptoms were more prominent in women with other conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as higher total cholesterol, elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure and higher fasting glucose than women without symptoms [26]. Women with symptoms also showed greater dilatation of the radial artery to nitroglycerin, and more calcification of the coronary arteries than asymptomatic women [76, 79]. These differences may reflect other underlying disease processes such as changes in endothelial function in addition to differences in autonomic control.

In light of the evidence that estrogen alters autonomic nerve activity via central stimulation of estrogen receptors, decreases in circulating estrogen would therefore be expected to alter the balance in parasympathetic (vagal tone) and sympathetic nerve activity. Accordingly, heart rate variability was lower in oophorectomized women compared to age-matched controls [48], suggesting decreased parasympathetic tone in these women. Although changes in heart rate variability may be associated with subclinical arterial calcification in women [27], this measurement has not gained widespread clinical utility to assess risk of cardiovascular disease or events.

In a more direct assessment of autonomic function, postmenopausal women exhibited elevated peripheral sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerve activity compared to young women [54, 82]. Augmented sympathetic nerve activity (and peripheral vasoconstriction) might contribute to the increased rate of hypertension in postmenopausal women [9]. These autonomic changes can be reversed with estrogen therapy [48, 82, 84]. The effect of estrogen therapy appears to be dependent on which type of estrogen is used; transdermal 17β-estradiol but not oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) appear to attenuate sympathetic nerve activity in postmenopausal women [82]. The difference in effects of the two types of products may reflect that transdermal 17β-estradiol is absorbed directly into the circulation and thus, bypasses immediated degradation in the liver. Conjugated equine estrogen contains multiple metabolites of 17β-estradiol including estrone and estrone sulphate and the oral product will be further metabolized by direct absorption from the gut and metabolism in the liver.

In young women, sympathetic nerve activity actually increased during the luteal phase (when estrogen and progesterone are elevated) compared to the early follicular phase when both hormones are low [51] suggesting that progesterone may also have an effect on central sympathetic outflow. Future studies should therefore consider both the separate and interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on the function of central autonomic nuclei.

Central stimulation of estrogen receptors also alters baroreflex sensitivity, or responsiveness. An increase in baroreflex sensitivity means that the baroreflex becomes more effective in buffering changes in arterial blood pressure. In ovariectomized female rats, acute and chronic estrogen administration increased cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity [63, 66], an effect that was blocked by administration of an estrogen receptor antagonist that was administered to the nucleus ambiguous [65]. However, effects of estrogen on baroreflex sensitivity in humans have yielded varying results. Minson et al [51] demonstrated that cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity was not different between the mid-luteal and early follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in young women, whereas, sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity was increased in the luteal phase. Hunt et al demonstrated that conjugated estrogen treatment in postmenopausal women did not affect cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity but increased sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity [35]. Conversely, a report from Vongpatanasin et al [82] indicated that neither transdermal or conjugated equine estrogen therapy increased baroreflex sensitivity in postmenopausal women. Due to the many potential targets of estrogen in neural and cardiovascular organs, some of the variability reported for effects of estrogen on baroreflex sensitivity may relate to heterogeneity in end-organ responsiveness to the hormone. More information is needed regarding the route and dose of estrogen treatments on baroreflex control in postmenopausal women and evaluation as to how these changes might relate to development and control of hypertension.

Central adrenergic receptors

Adrenergic receptors are distributed throughout the central nervous system and regulate neuronal release of neurotransmitters. Alterations in the expression/sensitivity of these pre- and post-synaptic receptors alters the activity of the central nuclei controlling sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow. Estrogen alters the sensitivity and/or expression of α-adrenergic receptors in rodent brains. For example, pre-synaptic α2-adrenergic receptor inhibition of norepinephrine release was reduced in hypothalamic brain slices derived from ovariectomized rats treated with estrogen. This decreased pre-synaptic inhibition increased the amount of norepinephrine released from the slice (Karkanais and Etgen, 1993). Conversely, estradiol treatment to ovariectomized rats increased post-synaptic α1b-adrenergic mRNA expression in the hypothalamus [38]. Taken together, these data suggest that estradiol administration increases turnover of norepinephrine in the brain and enhances post-synaptic norepinephrine signalling. Elevated norepinephrine turn-over in the sub-cortical regions of the brain is associated with increased sympathetic nerve activity in young and aging men [21]. Whether these levels of sympathetic nerve activity are related to age-dependent changes in testosterone or testosterone:estrogen ratio in men is unclear.

As discussed in other sections, exogenous administration of estrogen decreased sympathetic nerve activity in postmenopausal women, therefore, it seems contradictory that estradiol supplementation would decrease pre-synaptic inhibition of norepinephrine release in the brain. However, studies in cerebral cortex, in contrast to the hippocampus, indicate that both the α1a/d- and α2-adrenergic receptors are down-regulated by estrogen treatment in ovariectomized female rats [38]. Thus, effects of systemic administration of estradiol on the central α-adrenergic receptor are not well defined. Central effects of systemically administered hormone may depend on dose as well as synthesis and biodegradation of 17β-estradiol locally within the brain. The systemic concentration of 17β-estradiol or the bio-available product will be determined in part by the mode of administration as oral products degraded by first pass through the liver may not achieve the same circulating level of bio-available active ligands delivered subcutaneously or transdermally.

Central serotonergic receptors

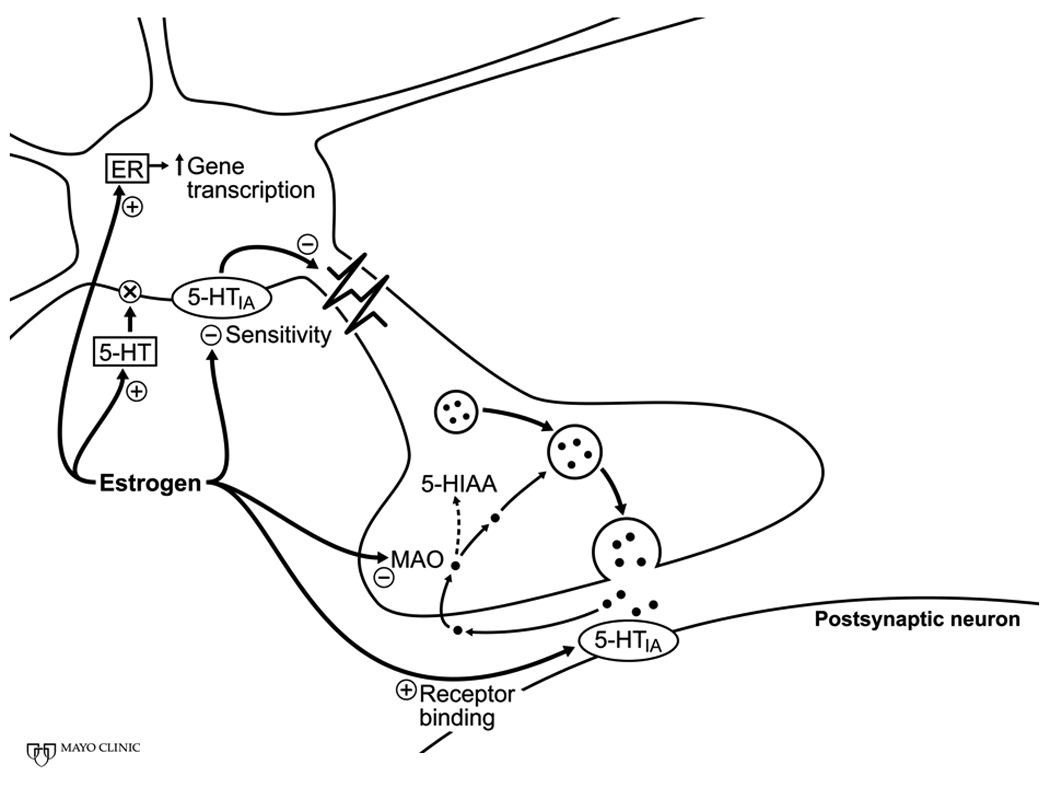

Other areas of the brain including areas of the brain stem involved with blood pressure regulation are innervated by serotonergic (5-hydroxytryptamine) neurons. Activation of certain serotonergic receptors can centrally inhibit/excite sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity (see[47] for review). Estrogen modulates several components of serotonergic neuronal activity including gene transcription in the neuronal nucleus. Estrogen also has two opposing effects on serotinergic signalling: estrogen augments activity of the serotonin uptake transporter which would reduce the duration of the serotonergic signal, but in contrast, estrogen inhibits monoamine oxidase, thus reducing degradation of the amine and increasing the duration of the signal (Fig. 3). Estrogen also augments sensitivity of 5-HT1A receptors on post-synaptic neurons which would also potentiate the neuronal signal as would increased sensitivity of the same receptor subtype on the pre-synaptic neuron, thus reducing presynaptic inhibition (see [15], Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of potential sites through which estrogen modulates serotonergic neuronal activity. Genomic actions of estrogen are reflected by increased gene transcription. Non-genomic actions of estrogen include activation of re-uptake transporters, inhibition of degradation of the transmitter and changes in receptor sensitivity. Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptors; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Revised from Figure 1 of reference [11].

Loss of estrogen as would occur at menopause would decrease the activity of the serotonergic system. This effect might be compounded by the interaction of the serotonergic pathways with adrenergic pathways [15]. The serotonergic system is implicated in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms of menopause as selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRI’s) as well as clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonist which activates pre-synaptic inhibition in the brain, may be effective in relieving menopausal vasomotor symptoms in some women [70].

Decreased serotonin and/or receptors are associated with depression and hypertension both of which may increase at menopause. Depression is associated with increased cardiovascular disease [32, 33, 57]. However, it is unclear as to whether depression is an independent risk factor or that the mental state of depression promotes lifestyles that increase cardiovascular risk (smoking, inactivity, poor diet, etc.). More work is needed to assess autonomic function in patients diagnosed with depression to better understand how central regulatory systems affect peripheral vascular function and development and progression of cardiovascular disease.

Summary and future directions

Both sex and hormones interact to modulate neuroeffector mechanisms that impact control of vascular tone. These interactions explain in part the greater incidence and younger age at which hypertension presents in men compared to women and the greater prevalence of vasomotor disorders in women. While many investigations have focused on how estrogen regulates neuronal function through actions on synthesis, release, degradation and uptake of transmitter at the neuroeffector junction much less is known about how testosterone, progesterone or corticosteroids would further modulate these processes. In addition, effects of the sex steroids on central nuclei associated with vasomotor control are complex. Additional studies are needed to better understand adrenergic and serotonergic interactions in the brain associated with mood disorders and cardiovascular risk. Other studies also need to focus on how genetic imprinting from the maternal or paternal chromosomes affects cardiovascular risk and to separate these effects from those modulated by the sex steroids.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: This work was supported in part by grants from NIH HL 083947, UL1 RR024150 and the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Miller is President of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences and serves on the Board of the Society for Women’rsquo;s Health Research.

References

- 1.Amandusson A, Hermanson O, Blomqvist A. Estrogen receptor-like immunoreactivity in the medullary and spinal dorsal horn of the female rat. Neurosci Lett. 1995;196:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11828-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anglin JC, Brooks VL. Tyrosine hydroxylase and norepinephrine transporter in sympathetic ganglia of female rats vary with reproductive state. Auton Neurosci. 2003;105:8–15. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(03)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus JA, Cocks TM, Satoh K. α2◻-adrenoceptors and endothelium-dependent relaxations in canine large arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;88:767–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb16249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold AP, Chen X. What does the "four core genotypes" mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball P, Knupen R, Haupt M, Breurer H. Kinetic properties of a soluble catechol O-methyltransferase of human liver. Eur J Biochem. 1972;26:560–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball P, Knuppen R. Formation, metabolism, and physiologic importance of catecholestrogens. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:2163–2170. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90558-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball P, Knuppen R, Haupt M, Breuer H. Interactions between estrogens and catechol amines. 3. Studies on the methylation of catechol estrogens, catechol amines and other catechols by the ctechol-O-methyltransferases of human liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1972;34:736–746. doi: 10.1210/jcem-34-4-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartelink ML, Wollersheim H, Theeuwes A, VanDuren D, Thien T. Changes in skin blood flow during the menstrual cycle: The influence of the menstrual cycle on the peripheral circulation in healthy female volunteers. Clin Sci. 1990;78:527–532. doi: 10.1042/cs0780527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–313. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Female reproductive hormones and thermoregulatory control of skin blood flow. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ, Johnson CP, Eisenach JH, Dietz NM, Wallin BG. Balance between cardiac output and sympathetic nerve activity in resting humans: role in arterial pressure regulation. J Physiol. 2005;568:315–321. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colucci WS, Gimbrone MA, Jr, McLaughlin MK, Halpern W, Alexander RW. Increased vascular catecholamine sensitivity and α-adrenergic receptor affinity in female and estrogen-treated male rats. Circ Res. 1982;50:805–811. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke JP, Mrshall JM. Mechanisms of Raynaud'rsquo;s Disease. Vasc Med. 2005;10:293–307. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm639ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crandall CJ, Crawford SL, Gold EB. Vasomotor symptom prevalence is associated with polymorphisms in sex steroid-metabolizing enzymes and receptors. Am J Med. 2006;119:S52–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deecher D, Andree TH, Sloan D, Schechter LE. From menarche to menopause: Exploring the underying biology of depression in women experiencing hormonal changes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du X-J, Dart AM, Riemersma RA, Oliver MF. Sex difference in presynaptic adrenergic inhibition of norepinephrine release during normoxia and ischemia in the rat heart. Circ Res. 1991;68:827–835. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Zacharia LC, Rosselli M, Korzekwa KR, Fingerle J, Jackson EK. Methoxyestradiols mediate the antimitogenic effects of estradiol on vascular smooth muscle cells via estrogen receptor-independent mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:27–33. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duckles SP, Miller VM. Hormonal Modulation of Endothelial NO Production. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2010;459:841–851. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ely D, Milsted A, Bertram J, Ciotti M, Dunphy G, Turner ME. Sry delivery to the adrenal medulla increases blood pressure and adrenal medullary tyrosine hydroxylase of normotensive WKY rats. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ely D, Milsted A, Dunphy G, Boehme S, Dunmire J, Hart M, Toot J, Martins A, Turner M. Delivery of sry1, but not sry2, to the kidney increases blood pressure and sns indices in normotensive wky rats. BMC Physiology. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-10. doi:10.1186/1472-6793-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esler M, Hastings J, Lambert G, Kaye D, Jennings G, Seals DR. The influence of aging on the human sympathetic nervous system and brain norepinephrine turnover. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R909–R916. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00335.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenoy FJ, Hernandez ME, Hernandez M, Quesada T, Salom MG, Hernandez I. Acute effects of 2-methoxyestradiol on endothelial aortic No release in male and ovariectomized female rats. Nitric Oxide. 2010;23:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrer M, Meyer M, Osol G. Estrogen replacement increases beta-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries. J Vasc Res. 1996;33:124–131. doi: 10.1159/000159140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman RR, Girgis R. Effects of menstrual cycle and race on peripheral vascular α-adrenergic responsiveness. Hypertension. 2000;35:795–799. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland EM, Hahn MK, Ketch TP, Keller NR, H KC, Kim KS, Biaggioni I, Shannon JR, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Genetic basis of clinical catecholamine disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;971:506–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gast GCM, Samsioe GN, Grobbee DE, Nilsson PM, van der Schouw YT. Vasomotor symptoms, estradiol levels and cardiovascular risk profile in women. Maturitas. 2010;66:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianaros PJ, Salomon K, Zhou F, Owens JF, Edmundowicz D, Kuller LH, Matthews KA. A greater reduction in high-frequency heart rate variability to a psychological stressor is associated with subclinical coronary and aortic calcification in postmenopausal women. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:553–560. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170335.92770.7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giltay EJ, Bunck MC, Gooren LJ, Zitman FG, Diamant M, Teerlink T. Effects of sex steroids on the neurotransmitter-specific aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan in transsexual subjects. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;88:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000135710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gundlah C, Kohama SG, Mirkes SJ, Garyfallou VT, Urbanski HF, Bethea CL. Distribution of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) mRNA in hypothalamus, midbrain and temporal lobe of spayed macaque: continued expression with hormone replacement. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamlet MA, Rorie DK, Tyce GM. Effects of estradiol on release and disposition of norepinephrine from nerve endings. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:H450–H456. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.4.H450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Wallin GG, Curry TB, Eisenach JH, Joyner MJ. Sex Differences in Sympathetic Neural-Hemodynamic Balance: implications for human blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 2009;53:571–576. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.126391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haukkala A, Konttinen H, Uutela A, Kawachi I, Laatikainen T. Gender differernces in the associations between depressive sumptoms, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes S. Broken-hearted women: the complex relationship between depression and cardiovascular disease. Women's Health. 2009;5:709–725. doi: 10.2217/whe.09.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogarth AJ, Mackintosh AF, Mary DA. Gender-related differences in the sympathetic vasoconstrictor drive of normal subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:353–361. doi: 10.1042/CS20060288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt BE, Taylor A, Hamner JW, Gagnon M, Lipsitz LA. Estrogen replacement therapy improves baroreflex regulation of vascular sympathetic outflow in postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2001;103:2909–2914. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, Liu J, Ecelbarger CM, Watkins R, Arnold AP, Sandberg K. Sex Chromosome Effects Unmasked in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:1275–1282. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanasaki K, Palmsten K, Sugimoto H, Ahmad S, Hamano Y, Xie L, Parry S, Augustin HG, Gattone VH, Folkman J, Strauss JF, Kalluri R. Deficiency in catechol-O-methyltransferase and 2-methoxyoestradiol is associated with pre-eclampsia. Nature. 2008;453:1117–1121. doi: 10.1038/nature06951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karkanias GB, Ansonoff MA, Etgen AM. Estradiol regulation of alpha 1b-adrenoceptor mRNA in female rat hypothalamus-preoptic area. J Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:449–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.04716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur G, Janik J, Isaacson LG, Callahan P. Estrogen regulation of neurotrophin expression in sympathetic neurons and vascular targets. Brain Res. 2007;1139:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kellog D., Jr In vivo mechanisms of cutaneous vasodlation and vasoconstiction in humans during thermoregulatory challenges. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1709–1718. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01071.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kneale BJ, Chowienczyk PJ, Brett SE, Coltart DJ, Ritter JM. Gender differences in sensitivity to adrenergic agonists of forearm resistance vasculature. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koledova VV, Khalil RA. Sex hormone replacement therapy and modulation of vascular function in cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2007;5:777–789. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e1–e170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lloyd T, Weisz J. Direct inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase activity by catechol estrogens. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:4841–4843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Main JS, Forster C, Armstrong PW. Inhibitory role of the coronary arterial endothelium to à-adrenergic stimulation in experimental heart failure. Circ Res. 1991;68:940–946. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer AF, Schroeder C, Heusser K, Tank J, Diedrich A, Schmieder RE, Luft FC, Jordan J. Influences of norepinephrine transporter function on the distribution of sympathetic activity in humans. Hypertension. 2006;48:120–126. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000225424.13138.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCall RB, Clement ME. Role of serotonin1A and serotonin2 receptors in the central regulation of the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:231–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mercuro G, Podda A, Pitzalis L, Zoncu S, Mascia M, Melis GB, Rosano GM. Evidence of a role of endogenous estrogen in the modulation of autonomic nervous system. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:787–789. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00865-6. A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller VM, Aarhus LL, Vanhoutte PM. Effects of estrogens on adrenergic and endothelium-dependent responses in the ovarian artery of the rabbit. In: Halpern W, Brayden JE, McLaughlin M, Osol G, Pegram BL, Mackey K, editors. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Resistance Arteries. Ithaca, NY: Perinatology Press; 1988. pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller VM, Duckles SP. Vascular Actions of Estrogens: Functional Implications. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:210–241. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minson CT, Halliwill JR, Young TM, Joyner MJ. Influence of the menstrual cycle on sympathetic activity, baroreflex sensitivity, and vascular transduction in young women. Circulation. 2000;101:862–868. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moldovanova I, Shroeder C, Jacob G, Hiemke C, Diedrich A, Luft FC, J J. Hormonal influences on cardiovascular norepinephrine transporter responses in healthy women. Hypertension. 2008;51:1203–1209. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner MonteE, Amy Milsted CJ, Ely DanielL. Sex Chromosomes. Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology. 2004;34:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moreau KL, Donato AJ, Tanaka H, Jones PP, Gates PE, Seals DR. Basal leg blood flow in healthy women is related to age and hormone replacement therapy status. J Physiol. 2003;547:309–316. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Negrin CD, McBride MW, Carswell HVO, Graham D, Carr FJ, Clark JS, Jeffs B, Anderson NH, Macrae M, Dominiczak AF. Reciprocal consomic strains to evaluate Y chromosome effects. Hypertension. 2001;37:391–397. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Rourke S, Vanhoutte PM, Miller VM. Vascular Pharmacology. In: Creager MAVD, Loscalzo J, editors. Vascular Medicine, A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohira T. Psychological distress and cardiovascular disease: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) J Epidemiol. 2010;20:185–191. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orshal JM, Khalil RA. Gender, sex hormones, and vascular tone. Am J Physiol: Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R233–R249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00338.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Owens JF, Stoney CM, Matthews KA. Menopausal status influences ambulatory blood pressure levels and blood pressure changes during mental stress. Circulation. 1993;88:2794–2802. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paul SM, Axelrod J, Diliberto EJ., Jr Catechol estrogen-forming enzyme of brain: demonstration of a cytochrome p450 monooxygenase. Endocrinology. 1977;101:1604–1610. doi: 10.1210/endo-101-5-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Priviero FB, Leite R, Webb RC, Teixeira CE. Neurophysiological basis of penile erection. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2007;28:751–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reed AS, Tschakovsky ME, Minson CT, Halliwill JR, Torp KD, Nauss LA, Joyner MJ. Skeletal muscle vasodilatation during sympathoexcitation is not neurally mediated in humans. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 1):253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saleh MC, Connell BJ, Saleh TM. Autonomic and cardiovascular reflex responses to central estrogen injection in ovariectomized female rats. Brain Res. 2000a;879:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saleh MC, Connell BJ, Saleh TM. Medullary and intrathecal injections of 17beta-estradiol in male rats. Brain Res. 2000b;867:200–209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saleh TM, Connell BJ. Centrally mediated effect of 17beta-estradiol on parasympathetic tone in male rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R474–R481. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.2.R474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saleh TM, Connell BJ. 17beta-estradiol modulates baroreflex sensitivity and autonomic tone of female rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;80:148–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saleh TM, Connell BJ. Central nuclei mediating estrogen-induced changes in autonomic tone and baroreceptor reflex in male rats. Brain Res. 2003;961:190–200. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03928-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saleh TM, Cribb AE, Connell BJ. Role of estrogen in central nuclei mediating stroke-induced changes in autonomic tone. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:182–195. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(03)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandner P, Neuser D, Bischoff E. Erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2009;(191):507–531. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santoro N. Symptoms of menopause: hot flushes. Clinical Obstetrics &Gynecology. 2008;51:539–548. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31818093f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schroeder C, Adams F, Boschmann M, Tank J, Haertter S, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Luft FC, J J. Phenotypical evidence for a gender difference in cardiac norepinephrine transporter function. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory Integrative & Comparative Physiology. 2004;286:R851–R856. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00689.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sowers MR, Wilson AL, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Kardia SR. Sex steroid hormone pathway genes and health-related measures in women of 4 races/ethnicities: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Am J Med. 2006;119:S103–S110. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spary EJ, Maqbool A, Batten TF. Oestrogen receptors in the central nervous system and evidence for their role in the control of cardiovascular function. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;38:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sudhir K, Esler MD, Jennings GL, Komesaroff PA. Estrogen supplementation decreases norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction and total body norepinephrine spillover in perimenopausal women. Hypertension. 1997;30:1538–1543. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tesfamariam B, Weisbrod RM, Cohen RA. Endothelium inhibits responses of rabbit carotid artery to adrenergic nerve stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H792–H798. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.4.H792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Matthews KA. Hot Flashes and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease. Findings From the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;118:1234–1240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T. Nitric oxide and penile erectile function. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:233–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toda N, Okamura T. The pharmacology of nitric oxide in the peripheral nervous system of blood vessels. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:271–324. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuomikoski P, Ebert P, Groop PH, Haapalahti P, Hautamaki H, Ronnback M, Ylikorkala O, Mikkola TS. Evidence for a Role of Hot Flushes in Vascular Function in Recently Postmenopausal Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:902–908. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819cac04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Turner ME, Farkas J, Dunmire J, Ely D, Milsted A. Which Sry Locus Is the Hypertensive Y Chromosome Locus? Hypertension. 2009;53:430–435. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vila JM, De Aguilera EM, Martinez Cuesta MA, Martinez MC, Irurzun A, Lluch S. Endothelium attentuates contractile responses of goat saphenous arteries to adrenergic nerve stimulation. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1989;94C:431–434. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(89)90093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vongpatanasin W, Tuncel M, Mansour Y, Arbique D, Victor RG. Transdermal estrogen replacement therapy decreases sympathetic activity in postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2001;103:2903–2908. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang CI, Lewis RJ. Emerging structure-function relationships defining monoamine NSS transporter substrate and ligand affinity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weitz G, Elam M, Born J, Fehm HL, Dodt C. Postmenopausal estrogen administration suppresses muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:344–348. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wiinberg N, Hoegholm A, Christensen HR, Bang LE, Mikkelsen KL, Nielsen PE, Svendsen TL, Kampmann JP, Madsen NH, Bentzon MW. 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in 352 normal Danish subjects, related to age and gender. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:978–986. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Y, Davidge ST. Effect of estrogen replacement on vasoconstrictor responses in rat mesenteric arteries. Hypertension. 1999;34:1117–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]