Abstract

Background

HPV vaccine uptake is low among adolescent girls in the United States. We sought to identify l ongitudinal predictors of HPV vaccine initiation in populations at elevated risk for cervical cancer.

Methods

We interviewed a population-based sample of parents of 10–18 year-old girls in areas of North Carolina with elevated cervical cancer rates. Baseline interviews occurred in summer 2007 and follow-up interviews in fall 2008. Measures included health belief model constructs.

Results

Parents reported that 27% (149/567) of their daughters had initiated HPV vaccine between baseline and follow-up. Of parents who at baseline intended to get their daughters the vaccine in the next year, only 38% (126/348) had done so by follow-up. Of parents of daughters who remained unvaccinated at follow-up but had seen a doctor since baseline, only 37% (122/388) received an HPV vaccine recommendation.”

Rates of HPV vaccine initiation were higher among parents who at baseline perceived lower barriers to getting HPV vaccine, anticipated greater regret if their daughters got HPV because they were unvaccinated, did not report “needing more information” as the main reason they had not already vaccinated, intended to get their daughters the vaccine, or were not born-again Christians.

Conclusions

Missed opportunities to increase HPV vaccine uptake included unrealized parent intentions and absent doctor recommendations. While several health belief model constructs identified in early acceptability studies (e.g., perceived risk, perceived vaccine effectiveness) were not longitudinally associated with HPV vaccine initiation, our findings suggest correlates of uptake (e.g., anticipated regret) that offer novel opportunities for intervention.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, adherence, cervical neoplasia, health belief model

Introduction

Each year, an estimated 3,700 women in the United States die from cervical cancer,1 even though it is largely preventable through screening and early treatment. African Americans and women living in rural areas have higher rates of cervical cancer than white and urban-dwelling women.1,2 Promising new prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines prevent viral infections associated with 70% of cervical cancers.3,4 The US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends HPV vaccine for adolescent girls aged 11–12, with catch up for girls and women aged 13–26.5

HPV vaccine may be more likely to achieve its potential to reduce cervical disease, genital warts and other HPV-related cancers if it is widely disseminated to girls before first sexual intercourse, especially among populations at high risk.6 While uptake has increased since the US Food and Drug Administration approved quadrivalent HPV vaccine in June 2006, the proportion of adolescent girls initiating the first dose of the three dose HPV vaccine series has remained relatively low, at 37% in 2008.7 Uptake is markedly higher (~80%) in countries, like Australia and the United Kingdom, where school-based vaccine programs are more centralized and extensive than in the US.8, 9

Reasons for low HPV vaccine uptake remain unclear. Parent and physician behavior may be more important to vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in the US, where healthcare delivery is less centralized. Studies of willingness to receive HPV vaccine, conducted primarily before vaccine licensure among relatively homogenous populations, found that most parents and young adults approved of HPV vaccination.10 However, since vaccine licensing, only a few cross-sectional studies of HPV vaccine uptake have examined facilitators and barriers identified in the pre-licensing acceptability studies.11,12,13 Furthermore, no longitudinal studies have examined our previous assertion that the health belief model, which was developed in part to address vaccination behavior, is a useful rubric for thinking about predictors of HPV vaccine uptake.10 The model suggests that people get vaccines they think are safe, effective, doctor recommended, with few barriers to uptake, and addressing common and severe hazards.

We sought to characterize HPV vaccine initiation by a racially diverse sample of adolescent girls from both rural and urban areas with elevated rates of cervical cancer. We also sought to identify reasons for low HPV vaccine initiation rates, using a longitudinal study design that could yield results to inform future vaccine interventions and shed light on theoretical assumptions about correlates of uptake.

Methods

Settings and Participants

As part of the Carolina HPV Immunization Measurement and Evaluation (CHIME) Project14, trained staff conducted interviews using computer assisted telephone interviewing equipment. Baseline interviews occurred between July and October 2007, and follow-up interviews occurred in October and November 2008. Participants received ten dollars for completing each survey. The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina approved the study.

We selected North Carolina counties that had 1) high cervical cancer rates (defined as annual cervical cancer incidence >10 cases and annual cervical cancer mortality>4 deaths; cervical cancer statistics are per 100,000 women); 2) >20% African American residents; and 3) >1,500 girls in the targeted age range of 10–18 years. One county was urban (Cumberland) and four others were rural (Duplin, Harnett, Sampson, Wayne). Annual cervical cancer rates in these counties ranged from 10.2–13.9 incident cases during 1993–2003 and 4.2–6.5 deaths during 1994–2004, substantially higher than corresponding U.S. rates (8.6 incident cases and 2.9 deaths).15

Interviewers contacted a probability sample of households with telephone line access in these five counties using a dual-frame approach. Five percent of the sample came from a list-assisted random digit dialing telephone frame, while the remainder came from a non-overlapping targeted-list frame of directory-listed residential telephone numbers with available recent household demographic information. We stratified the samples at the telephone exchange level by concentration of African-American residents and rural versus urban status (based on U.S. Census 2000 block-level classification).16 We over-sampled households likely to contain an age-eligible female child or African Americans, as well as rural telephone exchanges.

Eligible households had to have 1 or more female children age 10–18 years. If a household had more than 1 eligible child, software randomly selected 1 as the index child for questions. Participants were parents, grandparents, or any other individual who self-identified as being responsible for the index child’s care. Interviewers attempted first to speak with female caregivers and then male caregivers if a female caregiver was unavailable. As most caregivers interviewed (97%) reported being the parent or guardian of the index child, for the sake of simplicity, we refer to caregivers as parents hereafter.

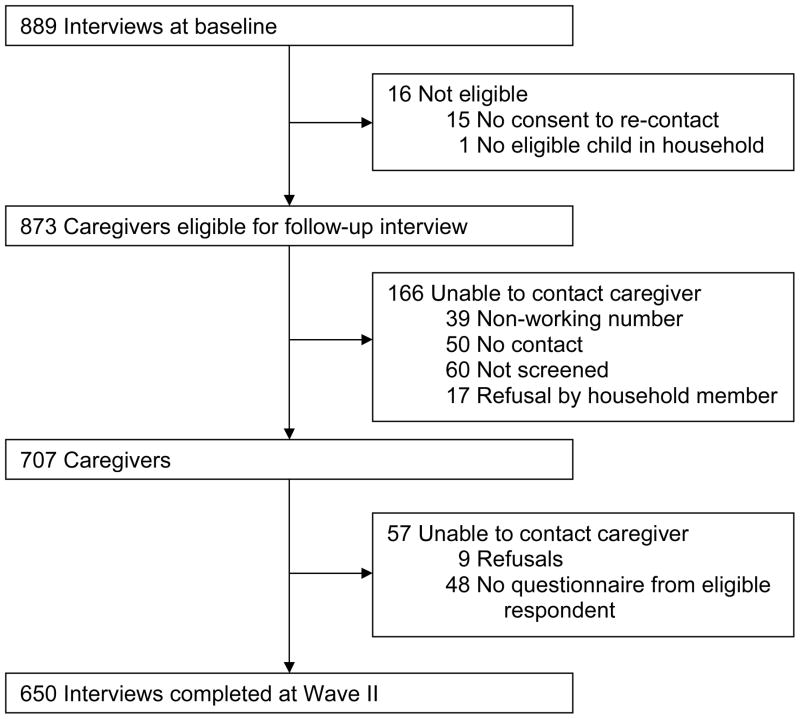

Interviewers completed baseline surveys with 889 (73%) of 1,220 eligible parents (flow diagram reported previously14). Interviewers completed follow-up surveys with 650 (74%) of 873 baseline respondents, after excluding 16 ineligible respondents (Figure 1). The mean age of parents was 41 (range 21–73), and their daughters’ mean age was 14 (range 10–18). Half lived in rural areas. The majority of parents completing follow-up interviews were non-Hispanic white (56%) or black (35%), had attended college (76%), and lived in households with incomes greater than $50,000 per year (57%). Parents who completed follow-up interviews and non-respondents had the same proportion of daughters who had initiated HPV vaccine at baseline and similar demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for follow-up interviews. Diagram for baseline interviews reported by Hughes et al., 2008.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants and non-respondents in follow-up interview.

| Non-respondents | Participants | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=239 | n=650 | ||

| n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | ||

| Daughter | |||

| Initiated HPV vaccine | 23 (7.3) | 83 (11.7) | .15 |

| Age | .55 | ||

| 10–12 years | 66 (33.3) | 184 (35.1) | |

| 13–15 years | 77 (30.2) | 219 (34.3) | |

| 16–18 years | 90 (36.5) | 247 (30.6) | |

| Health insurance | .75 | ||

| Private | 195 (74.0) | 540 (76.2) | |

| Public | 29 (20.2) | 80 (20.0) | |

| None | 14 (5.8) | 28 (3.8) | |

| Parent | |||

| Age, | .10 | ||

| <40 years | 82 (55.5) | 163 (46.0) | |

| 40+ years | 157 (45.5) | 487 (54.0) | |

| Sex | .51 | ||

| Female | 223 (91.9) | 612 (94.3) | |

| Male | 16 (8.1) | 38 (5.7) | |

| Race | .12 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 144 (43.6) | 480 (56.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 74 (43.4) | 132 (35.2) | |

| Hispanic or other | 21 (13.0) | 38 (8.6) | |

| Education | .09 | ||

| High school or less | 67 (34.2) | 123 (24.5) | |

| Some college or more | 172 (65.8) | 527 (75.5) | |

| Marital status | .15 | ||

| Married | 193 (73.5) | 557 (81.2) | |

| Other | 46 (26.5) | 93 (18.8) | |

| Annual household income | .10 | ||

| <$50,000 | 93 (48.7) | 195 (39.7) | |

| $50,000+ | 130 (45.4) | 430 (56.8) | |

| Missing | 16 (5.8) | 25 (3.47) | |

| Residence | .85 | ||

| Rural | 114 (46.1) | 323 (47.2) | |

| Urban | 126 (53.9) | 327 (52.8) | |

Note. Demographic data are from baseline interview. Non-respondents participated in baseline, but not follow-up, interviews.

Outcomes and Follow-Up

We assessed parents’ report of daughters’ receipt of one or more doses of HPV vaccine at baseline and follow-up. The primary outcome was HPV vaccine initiation at follow-up among daughters not vaccinated at baseline. We also assessed reported timely vaccine completion at follow-up, defined as having received all three doses or having received one or two doses but being not more than two months past the time recommended for receiving the next dose. The recommended HPV vaccine regimen at the time of the study was to receive the second dose 2 months after the initial dose, and the final dose at 6 months.5

Potential predictors of vaccine initiation included health belief model constructs (beliefs about likelihood and severity of cervical cancer; beliefs about HPV vaccine benefits, safety, and perceived barriers assessed using the Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CHIAS)17; and doctor’s recommendation) as well as demographic characteristics of parents and their daughters. The survey used an open-ended question to assess parents’ “main” reason for not having gotten their daughters HPV vaccine.

Statistical Analyses

We applied sampling weights to analyses (including percents, means, and risk ratios [RRs]) to account for the study design. Frequencies are not weighted. We used Poisson regressions to calculate RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for predictors of reported vaccine initiation (defined as one or more doses). Models examined predictors assessed during the baseline interview (except for political affiliation and being a born-again Christian, which we assessed at follow-up) and vaccine initiation assessed at follow-up, for daughters not vaccinated at baseline. We entered statistically significant bivariate predictors (p<.05) into a multivariate Poisson regression model. To identify items in multi-item scales that predicted vaccine initiation, we conducted post-hoc multivariate regressions controlling for other statistically significant multivariate predictors. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (College Station, TX), two-tailed tests, and critical alpha=.05.

Results

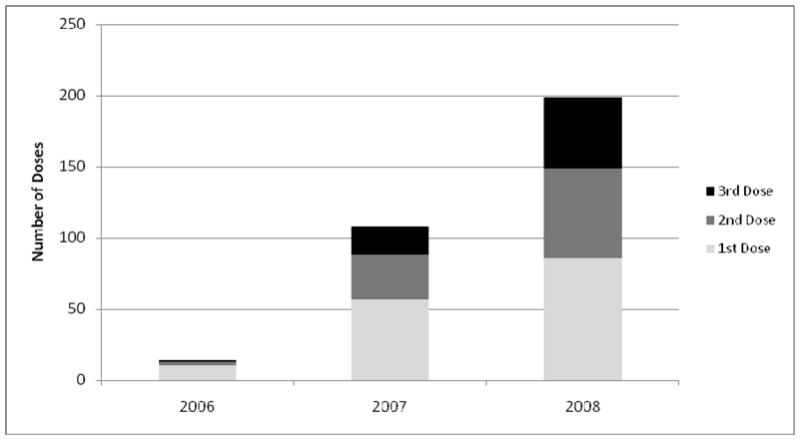

Parents reported increasing frequency of HPV vaccine initiation and completion over time (Figure 2), with most who initiated vaccine for their daughters doing so in 2008. At baseline, 12% (83/650) of parents said their daughters had initiated the three-dose HPV vaccine series. Of parents whose daughters had not initiated vaccine at baseline, 27% (149/567) reported their daughters had received vaccine by follow-up. Most parents of daughters who received any doses by follow-up reported their daughters had received all three doses (58%, 137/232) or had received one or two doses but were on schedule to complete the regimen within recommended time guidelines (28%, 60/232). Few parents reported vaccination dates that indicated their daughters were more than two months past the date recommended for the second dose (9%, 20/232) or final dose (6%, 15/232). Parents whose daughters had not initiated HPV vaccine at baseline (n=567) are the analytic sample for the rest of the paper.

Figure 2. Dates of HPV vaccine receipt by dose.

232 parents reported their daughters received 553 doses. Parents reported information on year delivered for 321 of these doses.

Reasons for not Vaccinating

At baseline, the most common reasons for not getting daughters HPV vaccine were that parents needed more information about the vaccine (21%, 110/567) and that their daughters were too young to get it (18%, 82/567) (Table 2). Only 3 parents said the main reason for not vaccinating was that it would cause their daughters to become sexually active. At follow-up, the main reason reported for not having vaccinated adolescent daughters was that they had not been to the doctor or gotten around to it yet (18%, 74/418).

Table 2.

Reasons parents gave for their daughters not receiving HPV vaccine

| Baseline (n=567) | Follow-up (n=418) | |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Needed more information | 21 | 13* |

| Daughter was too young | 18 | 9* |

| Never heard of vaccine | 12 | 7* |

| Daughter not having sex | 12 | 10 |

| Had not been to doctor/gotten around to it yet | 11 | 18 |

| Doctor did not recommend or discouraged vaccine | 9 | 6 |

| Vaccine was too new | 7 | 14* |

Note. Table presents parents’ most frequent responses to the question, “What is the main reason she has not gotten any HPV shots?” Interviewers accepted multiple answers but encouraged a single response. The 418 parents who gave answers at both interviews less often gave the first three reasons and more often gave the last one at follow-up.

p < .05.

Predictors of HPV Vaccine Initiation

Parents’ beliefs about HPV vaccine and their daughters were the main predictors of vaccine initiation (Tables 3–5). Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their daughters were associated with initiating HPV vaccination for their daughters in multivariate analyses (RR=2.04, 95%CI=1.16–3.59). During the baseline interview, 62% (348/567) of parents who had not obtained HPV vaccine for their daughters said that they intended to in the next year. However, only 38% (126/348) reported having done so by follow-up. This rate is higher than the 10% (23/219) vaccination rate among parents who did not intend to vaccinate or were unsure, but it represents a substantial number of motivated parents who were unable to fulfill their intentions. Most parents who reported at follow-up that they had not yet obtained HPV vaccine for their daughters intended to vaccinate their daughters within the next year (57%, 225/418).

Table 3.

Longitudinal predictors of parent-reported HPV vaccine initiation (categorical variables in unadjusted analyses).

| No. of parents reporting at follow-up that their daughters had received HPV vaccine/total no. of parents in predictor category (weighted %) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | ||

| HPV knowledge | ||

| Had not heard of HPV | 10/90 (19.9) | 1.10 (.39–3.07) |

| Low knowledge | 43/180 (18.2) | (ref) |

| High knowledge (>60% correct) | 96/297 (37.0) | 2.04 (1.21–3.42)** |

| HPV vaccine | ||

| Intended to vaccinate daughter | ||

| Probably or definitely will not/Do not know | 23/219 (9.7) | (ref) |

| Probably or definitely will | 126/348 (38.1) | 3.93 (2.13–7.25)** |

| Believed daughter was in age group HPV vaccine is recommended for | ||

| No | 9/73 (11.7) | (ref) |

| Yes | 140/494 (30.3) | 2.59 (1.02–6.56)* |

| Believed daughter’s health insurance covered HPV vaccine | ||

| No | 11/50 (20.4) | .49 (.22–1.08) |

| Maybe/Don’t know | 94/411 (23.1) | .55 (.34-.91)* |

| Yes | 44/106 (41.6) | (ref) |

| Daughter’s doctor recommended HPV vaccine | ||

| No | 103/473 (23.0) | (ref) |

| Yes | 46/94 (51.0) | 2.22 (1.43–3.43)** |

| Reasons stated for not getting daughter HPV vaccine | ||

| Needed more information | ||

| No | 128/457 (31.7) | (ref) |

| Yes | 21/110 (10.9) | .34 (.18-.64)** |

| Daughter was too young | ||

| No | 134/485 (26.3) | (ref) |

| Yes | 15/82 (32.0) | 1.24 (.64–2.29) |

| Never heard of HPV vaccine | ||

| No | 142/514 (27.8) | (ref) |

| Yes | 7/53 (24.1) | .87 (.31–2.45) |

| Daughter not having sex | ||

| No | 135/499 (27.1) | (ref) |

| Yes | 14/68 (29.4) | 1.09 (.54–2.17) |

| Had not been to doctor/gotten around to it yet | ||

| No | 115/476 (26.1) | (ref) |

| Yes | 34/91 (25.0) | 1.44 (.91–2.30) |

| Doctor did not recommend or discouraged HPV vaccine | ||

| No | 135/524 (26.6) | (ref) |

| Yes | 14/43 (35.2) | 1.32 (.60–2.91) |

| HPV vaccine was too new | ||

| No | 137/528 (27.9) | (ref) |

| Yes | 12/39 (20.5) | .74 (.31–1.77) |

| History of HPV-related disease | ||

| Had cervical cancer (mother or someone parent cared about) | ||

| No | 98/394 (28.3) | (ref) |

| Yes | 51/173 (25.0) | .88 (.56–1.40) |

| Had genital warts (parent or someone parent cared about) | ||

| No | 122/456 (29.9) | (ref) |

| Yes | 27/111 (17.4) | .58 (.32–1.05) |

| Mother had hysterectomy1 | ||

| No | 118/439 (29.6) | (ref) |

| Yes | 23/93 (18.1) | .61 (.33–1.12) |

| Mother had abnormal pap test result1 | ||

| No | 56/212 (26.0) | (ref) |

| Yes | 62/225 (32.1) | 1.23 (.76–2.00) |

| Daughter demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 10–12 years | 34/167 (27.8) | (ref) |

| 13–15 years | 57/194 (28.5) | 1.02 (.58–1.81) |

| 16–18 years | 58/206 (25.3) | .91 (.51–1.62) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 124/468 (27.7) | (ref) |

| Public only | 17/71 (26.0) | .94 (.46–1.92) |

| None | 8/26 (29.7) | 1.07 (.48–2.38) |

| Parent demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| <40 years | 41/146 (31.3) | (ref) |

| 40+ years | 108/421 (23.3.) | .74 (.48–1.46) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 141/532 (27.4) | (ref) |

| Male | 8/35 (27.1) | .99 (.38–2.59) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 114/415 (28.6) | (ref) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 24/116 (24.9) | .87 (.48–1.60) |

| Hispanic or other | 11/36 (31.5) | 1.10 (.57–2.14) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 20/114 (18.7) | (ref) |

| Some college or more | 129/453 (30.7) | 1.64 (.75–3.61) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 133/489 (25.8) | (ref) |

| Other | 16/78 (33.6) | 1.30 (.66–2.55) |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$60,000 | 55/230 (27.5) | (ref) |

| $60,000+ | 87/311 (27.8) | 1.01 (.64–1.61) |

| Missing | 6/23 (20.1) | .73 (.26–2.10) |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 83/283 (31.0) | (ref) |

| Urban | 66/284 (24.3) | .78 (.49–1.26) |

| Political affiliation | ||

| Conservative | 79/322 (26.0) | (ref) |

| Moderate or liberal | 69/242 (28.8) | 1.04 (.83–1.30) |

| Born again Christian | ||

| No | 62/199 (41.9) | (ref) |

| Yes | 86/365 (18.7) | .45 (.30-.67)*** |

Note. Predictors assessed in baseline interview, except for political affiliation and being a born-again Christian. Outcome assessed at follow-up. Analyses included parents who reported at baseline their daughters had not received any doses of HPV vaccine. RR = risk ratio. CI = confidence interval. (ref) = referent group.

p<.05,

p<.001

Asked only of mothers.

Table 5.

Longitudinal predictors of reported HPV vaccine initiation, adjusted analysis.

| aRR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Intend to vaccinate | 2.04 (1.16–3.59)* |

| HPV knowledge | |

| Had not heard of HPV | 1.17 (.57–2.42) |

| Low knowledge | (ref) |

| High knowledge | 1.49 (.96–2.30) |

| Believed daughter was in age group HPV vaccine is recommended for | 1.69 (.93–3.08) |

| Believe daughter’s health insurance covers HPV vaccine | |

| No | .82 (.36–1.88) |

| Maybe/Don’t know | .80 (.54–1.19) |

| Yes | (ref) |

| Daughter’s doctor recommended HPV vaccine | 1.20 (.83–1.74) |

| Needed more information about vaccine | .41 (.22-.76)** |

| Born again Christian | .53 (.39-.74)** |

| Perceived barriers to getting daughter HPV vaccine | .57 (.39-.83)** |

| Perceived harms of HPV vaccine | .79 (.51–1.23) |

| Perceived uncertainty about HPV vaccine | 1.12 (.84–1.53) |

| Anticipated regret (if do not get daughter HPV vaccine and she gets HPV) | 1.85 (1.13–3.02)* |

Note. Predictors assessed in baseline interview, except being a born-again Christian. Outcome assessed at follow-up. Adjusted analyses, which included parents who reported at baseline their daughters had not received any doses of HPV vaccine, controlled for all other variables in table. aRR = adjusted risk ratio. CI = confidence interval. (ref) = referent group.

p<.05,

p<.001

Doctor’s recommendation was associated with vaccine initiation, but only in bivariate analyses (Table 3). Few parents said at baseline that a health care provider had recommended they get HPV vaccine for their daughters (22%, 153/650). About half of parents who had received a doctor’s recommendation but had not acted on it before the baseline interview did so during follow-up (51%, 46/94) compared to 21% (103/473) of parents who had not received a recommendation before the baseline interview. Parents of all but a few daughters who had not initiated HPV vaccination at baseline reported they had been to their doctor between baseline and follow-up (97%, 533/563; data not available for 4 parents). Of these parents, 28% (145/533) had initiated vaccination for their daughters by follow-up. Of the remaining parents, only 1 in 3 reported receiving doctors’ recommendations for HPV vaccine (37%, 122/388), suggesting missed opportunities.

In multivariate analyses, parents were more likely to have gotten the vaccine for their daughters if they anticipated greater regret if not vaccinating did not protect their daughters from HPV infections (RR=1.85, 95%CI=1.13–3.02) (Table 5). Not initiating the vaccine was associated with being a born again Christian (RR=.53, 95%CI =.39-.74), perceiving greater barriers to getting the vaccine (RR=.57, 95%CI=.39-.83) or reporting that needing more information was the main reason for not having vaccinated at baseline (RR=.41, 95%CI=.22-.76). Removing intentions from the multivariate model did not affect any variables’ level of statistical significance. Perceived likelihood did not interact with perceived severity to predict vaccine initiation (data not shown, p= .96).

Post-hoc analyses of the five items in the perceived barriers scale found that parents who reported their daughters had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine said it would be somewhat or very hard to find a provider or clinic that stocked the vaccine (4%, 11/149) less often than parents who reported their daughters had received no vaccine doses (14%, 45/418, p<.05). Vaccinators also said it would be hard to find a provider or clinic where the vaccine would be affordable (20%, 41/149) less often than parents who reported their daughters had received no vaccine doses (35%, 143/418, p<.05). Vaccine uptake was not associated with the remaining perceived barriers items (finding a provider or clinic that is easy to get to, finding a provider or clinic that has convenient appointments, and being able to pay for the vaccine).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, predictors of HPV vaccine initiation among adolescent girls differed from those suggested by HPV vaccine acceptability studies conducted primarily before vaccine licensure.10 Many health belief model constructs that we expected would be associated with uptake were not. Instead, key predictors of initiation included anticipated regret if their daughters got HPV that the vaccine could have prevented as well as not being a born-again Christian. While many studies have examined interest in a hypothetical HPV vaccine or cross-sectional correlates of vaccine initiation,10–13,19 this study adds important new information on predictors over time.

Over two years after HPV vaccine became available to the public, only about one in three eligible girls in an area with elevated cervical cancer rates had initiated the vaccine. This vaccine uptake is similar to that found in other US studies from the same time period.7 It is also similar to coverage for another adolescent vaccine (tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis vaccine) about two years after its introduction in the US (30% in 2007).18,7 Our findings suggest missed opportunities to increase HPV vaccine uptake, including a large percentage of daughters who had been seen by their doctors but had not received an HPV vaccine recommendation, and two thirds of parents who intended to vaccinate their daughters but had not followed through with these plans a year later. One positive finding was parents’ report that most girls who had received the vaccine were on schedule to receive their next dose or had received all three doses.

In contrast to what we previously found in cross-sectional analyses of our baseline data on uptake11 and in our systematic review of acceptability,10,12 HPV vaccine initiation was not longitudinally associated with key health belief model constructs (perceived risk, perceived severity, and physician recommendation as a cue to action). The small and not statistically significant associations with risk beliefs were within the range we observed in our previous meta-analysis of vaccine use among adults.27 However, the observed associations were much smaller than associations with anticipated regret from not vaccinating. While the special predictive power of anticipated regret from not vaccinating mirrors the findings of Weinstein and colleagues,29 we additionally show that anticipated regret from vaccinating, at least with respect to sexual disinhibition, played essentially no role in vaccine decisions. This finding may be due to the different outcomes (cervical disease versus sexual disinhibition), or it may reflect different beliefs about harms caused by action and inaction.30

Doctor’s recommendation predicted reported HPV vaccine initiation in bivariate analyses, which is consistent with previous findings that doctors are uniquely credible and persuasive on issues related to medical care.25,26 The non-significant multivariate association may underestimate the importance of doctors’ recommendations, because our longitudinal analyses evaluated vaccine initiation over time according to doctors’ recommendations assessed at the baseline interview. As analyses only included those not yet vaccinated at baseline, daughters with doctor’s recommendations were those who had gotten a recommendation before baseline, but had not acted on it, and thus were perhaps less likely to be vaccinated later. Physicians could play a larger role in encouraging HPV vaccine initiation by adolescent girls and in providing information about the vaccine to parents.

Uptake was lower among parents who said they needed more information about the vaccine. Messages from doctors or other respected professionals that focus on helping parents who already plan to act and reducing perceived barriers may be especially effective in increasing HPV vaccine uptake. Conversations about consequences of vaccination, such as potential side effects, may be better redirected to focus on the consequences of not vaccinating (e.g., anticipated regret). Simply imagining–and anticipating–regretting a future in which their daughters had HPV was a powerful motivator for parents.

Born-again Christian parents in our study were half as likely as other parents to get their daughters HPV vaccine. This especially concerning, given that as many as 34% of the US population identify themselves in this way.20 A study in California found that born-again and evangelical Christian parents were less likely than other parents to prefer to vaccinate their daughters before age 13 than at older ages,21 but the study did not address the more fundamental question of willingness to get the vaccine at all or vaccine uptake. Our findings suggest public health programs to increase HPV vaccine uptake should make special efforts to reach born-again Christian parents.

Importantly, we found no differences in vaccine initiation by race, urbanicity, or age group. Equivalent but low uptake by whites and blacks will maintain, but not reduce, that U.S. black women’s sharply higher risk of dying from cervical cancer1. Given the current low rates of vaccine uptake in the US, additional efforts should focus in ensuring that HPV vaccine uptake is high across all groups, but these efforts should also especially focus on those at highest risk. We previously reported higher uptake among older teens in analyses of our baseline data.22 The different findings might reflect a previous desire to catch older teens up to recommended vaccine guidelines or parents now being more comfortable with recommendations to vaccinate younger adolescent girls. Because HPV vaccine is likely to be most effective if given before adolescent girls initiate sexual activity, it may even be preferable to have higher rates of uptake for younger aged adolescent girls.

Study strengths include a diverse, population-based sample of parents from high-risk areas. The study’s longitudinal design is also a strength, although we cannot completely rule out confounding by unmeasured variables. Limitations include the use of parent self-report to assess HPV vaccination of their female daughters. While studies have not yet examined accuracy of self-reported HPV vaccine initiation, adults’ self-report of having received influenza vaccine is reasonably sensitive and specific.23,24 The generalizability of the findings to other populations is not yet known.

HPV vaccine research is important in groups at highest risk for cervical cancer, including African Americans and Latinas who have high cervical cancer mortality rates and people living in rural areas with diminished access to care. Our study’s findings lay the foundation for interventions designed to increase vaccine uptake in these and likely other populations. Furthermore, interventions will increasingly need to focus on demographic groups with low rates of vaccinating their daughters against HPV.

Table 4.

Longitudinal predictors of parent–reported HPV vaccine initiation (continuous variables in unadjusted analyses).

| Weighted mean (weighted SD) | RR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated by follow-up (n=149) | Not vaccinated by follow-up (n=418) | ||

| Vaccine beliefs (CHIAS) | |||

| Perceived effectiveness of HPV vaccine 1 | 2.45 (.55) | 2.35 (.59) | 1.23 (.91–1.67) |

| Perceived barriers to getting daughter HPV vaccine 2 | 1.50 (.47) | 1.73 (.59) | .56 (.38-.83)** |

| Perceived harms of HPV vaccine 3 | 1.95 (.40) | 2.23 (.58) | .47 (.31-.70)** |

| Perceived uncertainty about HPV vaccine 3 | 2.57 (.84) | 3.01 (.74) | .62 (.46-.84)** |

| Beliefs about daughter | |||

| Anticipated regret (if do not get daughter HPV vaccine and she gets HPV) 4 | 3.92 (.36) | 3.54 (.87) | 2.64 (1.56–4.46)** |

| Anticipated regret (if daughter became more sexually active because she got HPV vaccine) 4 | 2.92 (1.26) | 2.70 (1.19) | 1.12 (.93–1.34) |

| Perceived likelihood of daughter getting cervical cancer 5 | 2.50 (.73) | 2.44 (.68) | 1.09 (.79–1.51) |

| Perceived severity of cervical cancer if daughter got it1 | 3.65 (.64) | 3.61 (.67) | 1.07 (.65–1.77) |

Note. Predictors assessed in baseline interview, except for political affiliation and being a born-again Christian. Outcome assessed at follow-up. Response scales ranged from 1 to 4, with higher values indicating stronger endorsement of the belief; see footnotes for response scale labels. CHIAS = Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale. CHIAS assessed vaccine beliefs using 2 items (effectiveness), 5 items (barriers), 6 items (harms) and 3 items (uncertainty); the remainder were single-item measures. Analyses included parents who reported at baseline their daughters had not received any doses of HPV vaccine. RR = risk ratio. CI = confidence interval. RRs report increase in vaccination associated with each unit increase in predictor.

p<.001

Response scale: slightly (coded as 1), moderately (2), very (3), and extremely (4).

Response scale: not hard at all (coded as 1), somewhat hard (2.5), and very hard (4); except for one item which used: strongly disagree (1), somewhat disagree (2), somewhat agree (3), and strongly agree (4).

Response scale: strongly disagree (coded as 1), somewhat disagree (2), somewhat agree (3), and strongly agree (4).

Response scale: not at all (coded as 1), a little (2), a moderate amount (3), and a lot (4).

Response scale: no chance (coded as 1), low (2), moderate (3), and a high chance (4).

Acknowledgments

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (S3715-25/25) funded the study, with additional support for Dr. Brewer from the American Cancer Society (MSRG-06-259-01-CPPB) and for Dr. Reiter from the Cancer Control Education Program at Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (Grant No. R25 CA57726). Three co-authors from the CDC (SG, NL, LM) participated in conducting the study and in preparing and submitting this article, though they did not participate in the decision to fund the study. Noel T. Brewer received a research grant from Merck for an unrelated study of men’s attitudes toward HPV vaccination in 2008–2009; Jennifer S. Smith received research grants, contracts, honoraria or consulting fees during the last four years from GlaxoSmithKline and Merck.

We thank colleagues who provided feedback on the study results and on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Portions of this paper were presented at the 2009 meeting of the American Public Health Association.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benard VB, Coughlin SS, Thompson T, Richardson LC. Cervical cancer incidence in the United States by area of residence, 1998–2001. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):681–686. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000279449.74780.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(3):621–632. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, et al. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(11):1459–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn JA. Maximizing the potential public health impact of HPV vaccines: A focus on parents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(2):101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 Years --- United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(36):997–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shefer A, Markowitz L, Deeks S, et al. Early experience with human papillomavirus vaccine introduction in the United States, Canada and Australia. Vaccine. 2008;26 (Suppl 10):K68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brabin L, Roberts SA, Stretch R, et al. Uptake of first two doses of human papillomavirus vaccine by adolescent schoolgirls in Manchester: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1056–1058. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39541.534109.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, McRee AL, Smith JS. Parents’ health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(3):475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziarnowski KL, Brewer NT, Weber B. Present choices, future outcomes: Anticipated regret and HPV vaccination. Prev Med. 2009;48(5):411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, et al. Uptake of HPV vaccine: demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitudes. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes J, Cates JR, Liddon N, Smith JS, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Disparities in how parents are learning about the human papillomavirus vaccine. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(2):363–372. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Statisitics. http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats/index.php. Updated 2008.

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau. Census glossary. http://factfinder.census.gov/home/en/epss/glossary_a.html. Updated 2008.

- 17.McRee AL, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Smith JS. The Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CHIAS): Scale Development and Associations with Intentions to Vaccinate. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37(4):234–239. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c37e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broder KR, Cortese MM, Iskander JK, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-3):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimet GD, Liddon N, Rosenthal SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Allen B. Chapter 24: Psychosocial aspects of vaccine acceptability. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S3, 201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosmin BA, Keysar A, editors. American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) 2008. Hartford, CT: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT, Sternberg MR, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skull SA, Andrews RM, Byrnes GB, et al. Validity of self-reported influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status among a cohort of hospitalized elderly inpatients. Vaccine. 2007;25(25):4775–4783. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerman RK, Raymund M, Janosky JE, Nowalk MP, Fine MJ. Sensitivity and specificity of patient self-report of influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccinations among elderly outpatients in diverse patient care strata. Vaccine. 2003;21(13–14):1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Hamann T, Bernstein DI. Attitudes about human papillomavirus vaccine in young women. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(5):300–306. doi: 10.1258/095646203321605486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehner CW, Howe SR, Bernstein DI, Rosenthal SL. Viral sexually transmitted disease vaccine acceptability among college students. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(10):774–778. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078823.05041.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26:136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, Herrington J. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Ann of Beh Med. 2004;27:125–130. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinstein ND, Kwitel A, McCaul KD, Magnan RE, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Risk perceptions: assessment and relationship to influenza vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):146–51. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritov I, Baron J. Reluctance to vaccinate: omission bias and ambiguity. J Behav Decis Making. 1990;3:263–277. [Google Scholar]