Summary

It has been difficult to reconcile the absence of pathology and apparently normal behavior of mice lacking prion protein (PrP), referred to as Prnp0/0 mice, with a mechanism of prion pathogenesis involving progressive loss of PrPC-mediated neuroprotection. However, here we report that Prnp0/0 mice exhibit significant age-related defects in motor coordination and balance compared with mice expressing wild type Prnp on a syngeneic background, and that the brains of behaviorally-impaired Prnp0/0 mice display the cardinal neuropathological hallmarks of spongiform pathology and reactive astrocytic gliosis that normally accompany prion disease. Consistent with the appearance of cerebellar ataxia as an early symptom in an patients with Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), an inherited form of human prion disease, motor coordination and balance defects manifested in a transgenic (Tg) mouse model of GSS considerably earlier than the onset of end-stage neurodegenerative disease. Our results are consistent with a mechanism in which loss of normal PrPC function is an important pathological component of prion diseases.

Keywords: Prion, spongiform degeneration, PrPC neuroprotection

Introduction

The precursor-product relationship between the cellular and disease-associated forms of PrP, referred to as PrPC and PrPSc respectively, is well-established for prion replication. In contrast, the mechanism by which prions elicit brain damage and the relative contributions of PrPSc accumulation and PrPC depletion to this process remain unclear. Prion disorders are generally viewed as gain-of-function diseases with neuronal damage resulting from the accumulation of PrPSc. However, certain examples of natural and experimental prion disease occur without accumulation of detectable protease resistant PrPSc [1-4] and the time course of neurodegeneration is not equivalent to the time course of PrPSc accumulation in mice expressing lower than normal levels of PrPC [5]. Moreover, grafting experiments of PrPC-expressing neuroectodermal tissue into Prnp0/0 mouse brains convincingly demonstrated that PrPSc is not toxic to cells that do not express PrPC, even after long-term exposure [6].

While the prion resistant phenotype of Prnp0/0 mice and their inability to replicate infectivity [5, 7, 8] is in accordance with the prion hypothesis, Prnp0/0 mice have not been as definitive in resolving the physiological and possible pathological functions of PrPC. Because the gene encoding PrP is highly conserved among species and is ubiquitously expressed, it was anticipated that Prnp0/0 mice would display overt phenotypic deficits that would provide information about essential physiological functions of PrPC. In contrast to expectations, initial studies of Prnp0/0 mice produced in Zurich and Edinburgh indicated that they developed and behaved normally [9, 10]. While Prnp0/0 mice subsequently produced in Nagasaki developed a progressive ataxia and Purkinje cell degeneration at ~70 weeks of age [11], these defects were found to be the result of inappropriate and neurotoxic expression of the PrP-like protein, Doppel (Dpl), in the central nervous system (CNS) rather than loss of PrP function [12, 13].

While subtle phenotypic defects in the Zurich and Edinburgh Prnp0/0 knockout mouse strains suggested roles for PrPC in maintaining normal circadian rhythms [14], superoxide dismutase activity and protection from oxidative stress [15] and copper metabolism [16], the lack of overt phenotypic deficits raised the possibility that adaptive developmental changes might compensate for loss of PrPC function in Prnp0/0 mice. Arguing against this possibility, Tg mice in which expression of PrPC was suppressed in adult mice using a tetracycline-responsive trans-activator [17], or mice in which neuronal PrP was post-natally ablated [18], remained free of any abnormal phenotype.

Other lines of evidence contend that PrPC provides cellular protective functions, raising the possibility that their disruption features in prion pathogenesis. Hippocampal cells from Prnp0/0 mice were more sensitive than cells derived form wild-type mice to serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis, an effect rescued by PrPC or Bcl-2 [19], and cerebellar cells from Prnp0/0 mice were more sensitive to oxidative stress [20]. Also, overexpression of PrPC rescued Bax-induced cell death in primary human neurons [21]. A growing body of evidence suggests that cell surface-anchored PrPC may provide a neuroprotective signaling function [22, 23] raising the possibility that impairment of this function is a feature of prion pathogenesis. Consistent with this notion, Tg mice expressing non-membrane tethered PrP, while they replicate prions and accumulate PrPSc, do not develop clinical prion disease [24].

A neuroprotective role for PrPC raises the possibility that loss of normal PrPC function in the brains of patients expressing mutant PRNP alleles is a component of the pathology of inherited prion disorders [25]. GSS is one example of an autosomal dominant inherited prion disease in humans. A common form of GSS is linked to a missense mutation resulting in replacement of proline to leucine at codon 102, referred to as P102L. The clinical and neuropathological features of GSS have been reproduced in Tg mice overexpressing a mouse PrP gene with the corresponding mutation at codon 101 (P101L), referred to as Tg(GSS) mice [4, 26, 27].

Here we show that Tg mice expressing null or missense mutant Prnp alleles exhibit an age-dependent motor behavior deficit suggesting a function for PrPC in maintaining sensorimotor coordination. We also report that the brains of Prnp0/0 mice exhibit region-specific spongiform degeneration and reactive astrocytic gliosis which are neuropathological hallmarks of prion diseases. Impairment of sensorimotor function in Tg(GSS) mice prior to the onset of end-stage neurodegenerative disease suggests that loss of PrPC function is an early feature of prion pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice

The Zurich strain of Prnp0/0 mice, which were originally maintained on a mixed 129/Sv and C57BL/6 genetic background, were subsequently repeatedly crossed with wild-type FVB animals to produce FVB/Prnp0/0 mice [28]. Breeding pairs were obtained from Stanley Prusiner by way of George Carlson at the McLaughlin Research Institute, Great Falls, Montana, and an inbred colony was established and maintained at the University of Kentucky. The production and characterization of Tg(GSS)22 mice, which were originally produced on a FVB/Prnp0/0 background, has been described previously [4]. The Tg(GSS)22 line, which is homozygous for the MoPrP-P101L transgene, was also maintained as an inbred colony.

Determination of spontaneous prion disease

Groups of mice were monitored thrice weekly for the development of prion disease. The date of disease was recorded as the age at onset of progressive clinical symptoms of prion disease including truncal ataxia, hind-limb paresis, loss of extensor reflex and tail stiffening.

Histopathologic analysis

Animals whose death was obviously imminent were euthanized and their brains taken for histopathological studies. Brains were dissected rapidly after sacrifice of the animal and immersion fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and 10 μm thick coronal microtome sections were mounted onto positively charged glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for evaluation of spongiform degeneration. Following inactivation of endogenous peroxidases by incubation in 3% H2O2 in methanol, peroxidase immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the extent of reactive astrocytic gliosis using antibodies to glial fibrillary acidic protein. Detection was with Vectastain ABC reagents and slides were developed with diaminobenzidine.

Semi-Automated Lesion Profiling

Paraffin-embedded mouse brains were sectioned coronally to areas corresponding to the five levels of the brain that contained the 16 mouse brain regions of interest. Brain sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images of the each of the 16 brain regions were captured using a Photometrics Cool Snap digital camera and a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope. Each image was processed using Metamorph (Universal Imaging Corporation) version 6.2r6 software. The thresholding feature of this program was used to differentiate vacuoles from irrelevant background objects. Once a threshold was reached that maximized detection of true vacuoles, the software-processed vacuoles were measured using Metamorph’s auto-trace region tool which automatically delineates well-defined vacuole edges, records the area of each vacuole and integrates the number of vacuoles per field. Lesion density, the number of vacuoles per field, was plotted on the y-axis with the corresponding brain region on the x-axis using Prism GraphPad Prism 4 Software. Error bars represent the average number of vacuoles per field ± the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) in the brains of three age-matched mice per genotype.

Behavioral Testing

Rotarod testing was performed on groups of eight age-matched Tg(GSS)22, wild type FVB, FVB/Prnp0/0 mice using a Dual Species Economex Rotarod model #0207-003M (Columbus Instruments) Testing was initiated when mice were 60 days of age. Mice were tested within a conserved ~3 hour time period in the morning. Mice were trained for 3 consecutive days prior to the first official testing date by repeatedly placing the mice on the rod until they were able to remain on a rod rotating at a constant speed of 5 r.p.m./s. for 90 sec. In both training and official testing, during the first trial of the day, mice were placed on the stationary rod and allowed to become familiar with the environment for 1 minute before the rod motor was engaged. On each testing day, each mouse was tested for three trials with a 10 minute inter-trial resting period. For each consecutive trail, mice were allowed to become acquainted with the environment for 30 seconds. For testing, the rod motor was initially set at 5 r.p.m. with an acceleration rate of 0.3 r.p.m/sec for a maximum trial period of 180 seconds and performance was measured as latency to fall in seconds.

Results

Sensorimotor deficits are associated with loss of PrP function

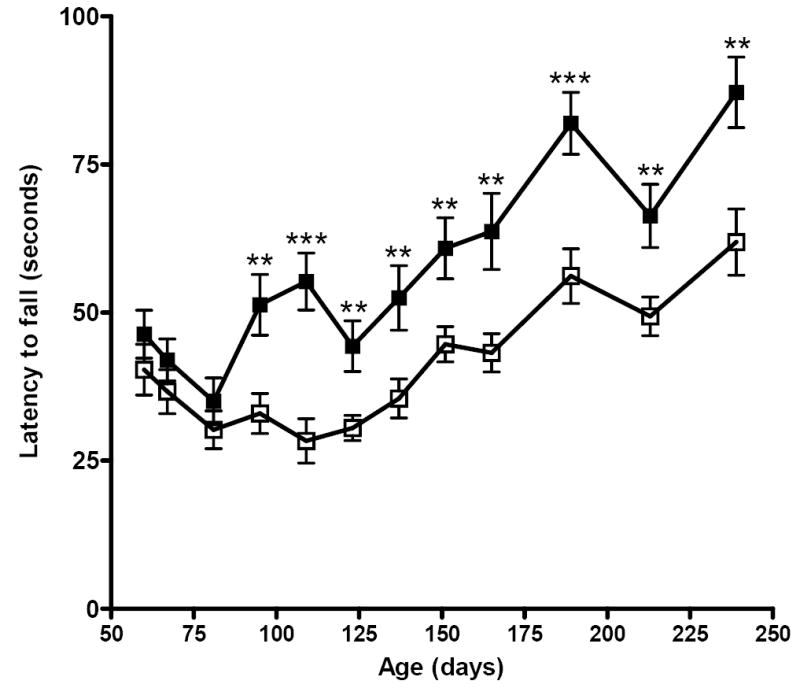

To evaluate whether loss of PrP function affected coordination and balance in Prnp0/0 mice we assessed performance on the Rotarod, a well-characterized behavioral task designed to assess motor function by requiring mice to ambulate on an accelerating rotating rod, with latency to fall as a measure of motor function. While there were no significant differences between the performances of young wild type FVB mice and Prnp0/0 mice that, apart from the Prnp null mutation, were otherwise syngeneic with FVB mice, after 95 d of age Prnp0/0 mice remained on the accelerating rod for an average of ~50% less time than wild type FVB mice over all testing dates between ~3 and 8 months of age. Differences in performance between Prnp0/0 and wild type FVB mice during this time were highly significant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Longitudinal analysis of motor and balance coordination of wild type FVB and Prnp0/0 mice on the rotarod.

Groups of 8 age-matched wild type FVB mice (filled squares) and Prnp0/0 mice (open squares) were subjected to rotarod behaviour analysis as described. Each mouse was tested three independent times on each test date. The mean latency to falling ± SEM was recorded for mice in each group on each date. Significant differences (p value < 0.05) between the mean performances of mice of different genotypes at each time point was established using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test with asterisks indicating the degree of significance between genotypes.

Neuronal vacuolar degeneration in Prnp0/0/FVB mice

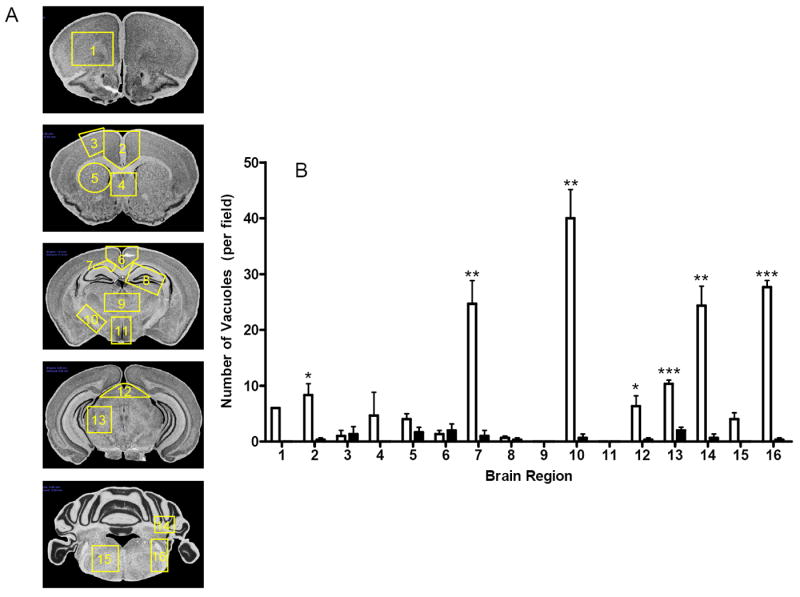

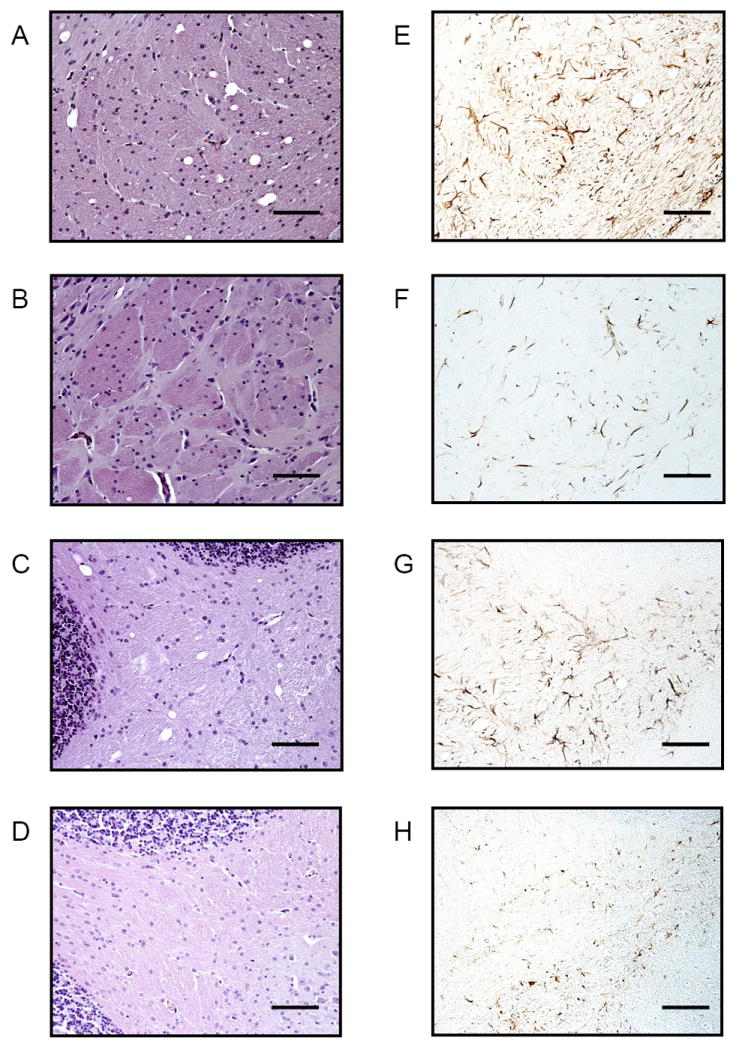

Microscopic examination of the CNS of patients or animals with prion disease typically reveals a characteristic triad of histopathological changes consisting of neuronal vacuolation and degeneration, which confers a microvacuolated or ‘spongiform’ appearance, and a reactive proliferation of glial cells. To assess whether the sensorimotor deficits we detected in older Prnp0/0 mice correlated with the presence of neuropathological lesions normally associated with prion disease, we assessed the histopathological profiles of multiple brain sections from Prnp0/0 mice and age-matched wild type FVB mice. To analyze vacuolar degeneration, we developed a semi-automated modification of the lesion profiling system developed by Fraser and Dickinson [29, 30] and quantified neuronal vacuolation in 16 brain regions (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, significant and reproducible spongiform pathology was present in the brains of Prnp0/0/FVB mice at 6 months of age (Figs. 2 and 4). Vacuolar lesion profiling showed that the corpus collosum at the level of the hippocampus (region 7), the medial globus pallidus (region 10), the cerebellum (region 14), and the inferior cerebellar peduncle and spinal trigeminal tract (region 16) were particularly affected regions in Prnp0/0 mice (Fig. 2B). Representative examples of spongiform degeneration and coincident reactive astrocytic gliosis in the brains of Prnp0/0 mice at the level of the medial globus pallidus and cerebellum are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2. Histopathological profiles of Prnp0/0 and wild type FVB mouse brains.

Using a semi-automated modification of the lesion profiling system we quantified neuronal vacuolation in 16 different brain regions shown in A. Images are adapted (with permission) from [46]. Regions are as follows: 1: forceps minor corpus collosum; 2: anterior midline cerebral cortex; 3: primary motor cortex; 4: para terminal body; 5: striatum; 6: posterior midline cerebral cortex; 7: corpus collosum at the level of the hippocampus; 8: hippocampus; 9: thalamus; 10: medial globus pallidus; 11: hypothalamus; 12: tectum (midbrain); 13: midbrain; 14: cerebellum; 15: dorsal medulla; 16: inferior cerebellar peduncle and trigeminal tract. B The mean (± SEM) number of vacuoles per field in each of 16 regions of the brains of three wild type FVB mice (solid bars) or three age-matched (at 6 months) Prnp0/0 mice (open bars) are shown. Significant differences (p value < 0.05) between the mean vacuolation score in each brain region was established using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test with asterisks indicating the degree of significance between genotypes.

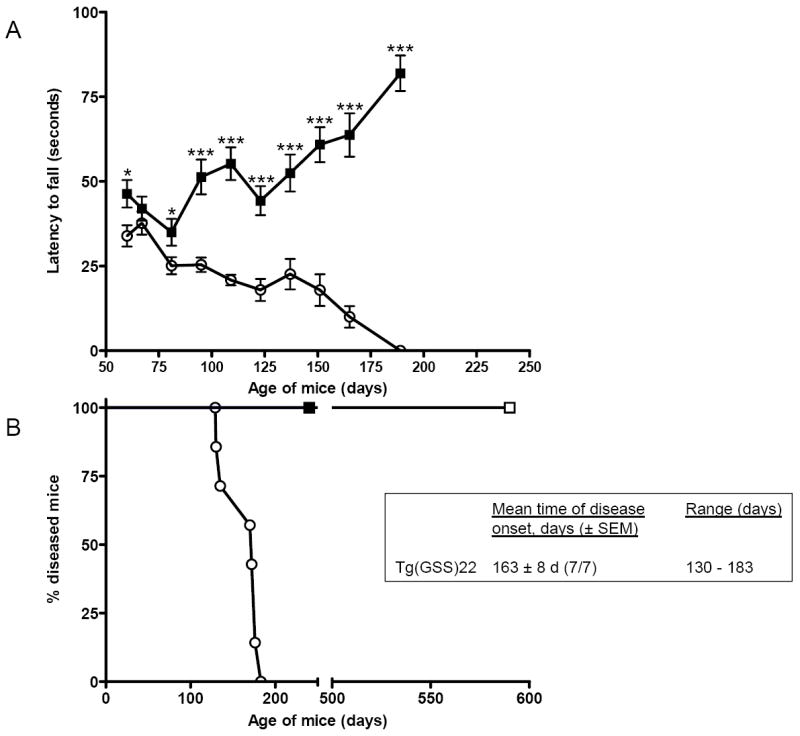

Fig. 4. Sensorimotor deficits precede the spontaneous onset of neurodegenerative disease in Tg(GSS)22 mice.

A Groups of 8 age-matched wild type FVB mice and Tg(GSS)22 mice were subjected to rotarod behaviour analysis as described. Each mouse was tested three independent times on each test date. The mean latency to falling ± SEM was recorded for mice in each group on each date. Filled squares signify the performance of FVB mice, while open circles signify the performance of Tg(GSS)22 mice. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between the mean performances of mice of different genotypes at each time point was established using an unpaired t test with asterisks indicating the degree of significance between genotypes. B Spontaneous neurodegenerative disease in Tg(GSS)22 mice. Open circles signify Tg(GSS)22 mice; filled squares signify the performance of wild type FVB mice, none of which (n=8) developed disease in the same time frame; and, in accordance with previous results [27], spontaneous disease did not occur in Tg(MoPrP)4112 mice overexpressing wild type mouse PrP (open squares) up to 590 d of age (n=5 mice).

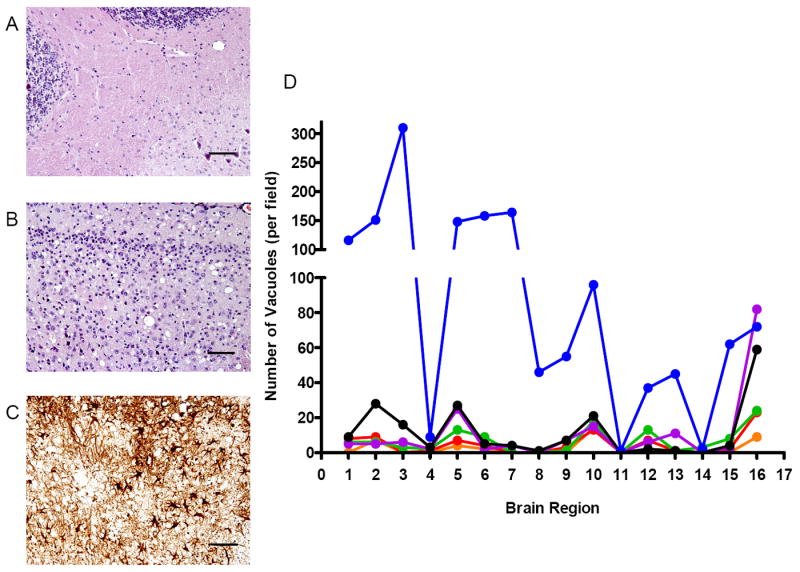

Fig. 3. Spongiform degeneration and astrocytic gliosis in the brains of Prnp0/0 mice.

The extent of spongiform degeneration in the brains of Prnp0/0 and age-matched (6 months) wild type FVB mice was determined in hematoxylin and eosin stained brain sections, while peroxidase immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the extent of reactive astrocytic gliosis using antibodies to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). A - D Hematoxylin and eosin staining, E - H GFAP immunohistochemistry of brain sections through the medial globus pallidus (region 10) and cerebellum (region 14) of Prnp0/0 and wild type FVB mice. A and E: medial globus pallidus of Prnp0/0 mice; B and F: medial globus pallidus of wild type FVB mice; C and G: cerebellum of Prnp0/0 mice; D and H: cerebellum of wild type FVB mice. Bar = 100 microns.

Sensorimotor deficits precede the onset of spontaneous neurodegeneration in Tg(GSS) mice

The neuromotor deficits and prion disease-related neuropathology in aged mice expressing a null Prnp allele suggests that loss of normal PrPC function is an important pathological component of prion disease and raises the possibility that progressive loss of PrPC function contributes to the pathogenesis of inherited prion diseases. To investigate whether motor behavioral impairments also occurred in mice expressing a missense Prnp allele, we evaluated the performances of Tg(GSS) mice of different ages and age-matched wild type FVB mice on the accelerating rotarod (Fig. 1). As reported previously [4], all Tg(GSS)22 mice overexpressing mutant mouse PrP-P101L, spontaneously developed a progressive neurological disorder with a mean age of onset of 163 ± 8 d (± standard error of the mean, n = 7) (Fig. 3A). However, sensorimotor deficits manifested considerably earlier than the onset of these neurological symptoms. Significant impairments of motor coordination and balance in Tg(GSS)22 mice were detected as early as 60 d of age, which was 70 d earlier than the time at which the first Tg(GSS)22 mice spontaneously developed neurological signs, and >100 d earlier than the mean age of spontaneous disease in Tg(GSS) mice (Fig. 3A). The performance of Tg(GSS)22 mice on the rotarod progressively deteriorated. After 95 d of age, extreme deficits in rotarod performance were consistently observed in Tg(GSS)22 mice compared to wild type FVB mice until the end stage of disease, at which point the ataxic phenotype made it impossible for Tg(GSS)22 mice to remain on the rod. As a result of the sensorimotor deficits in Prnp0/0 mice, the differences in performance between Tg(GSS)22 and Prnp0/0 mice did not become significant until mice were 123 d of age which was only one week before the first Tg(GSS)22 mice spontaneously developed neurologic signs, and 40 d earlier than the mean age of spontaneous disease.

Kinetics of vacuolar degeneration parallel PrPSc accumulation in the brains of Tg(GSS) mice

Previous studies using the PrPSc-specific monoclonal antibody (Mab) 15B3, showed that, while the levels of total MoPrP-P101L in the brains of Tg(GSS)22 mice remained constant as mice aged, substantial quantities of the pathological form of MoPrP-P101L accumulated immediately prior to the onset of clinical symptoms [4]. We were therefore interested to ascertain whether the development of neuropathological lesions in the brains of aging Tg(GSS)22 mice followed similar kinetics.

Coincident with the accumulation of mutant MoPrPSc-P101L in the brains of sick Tg(GSS)22 mice, the appearance of severe spongiform degeneration and accompanying reactive astrocytic gliosis was abrupt and did not appear until the end stage of disease when Tg(GSS)22 mice displayed an overt clinical phenotype. The most profoundly affected brain regions, with more than 150 vacuoles occupying each observation field, were the primary motor cortex (region 3), striatum (region 5), the posterior mid-line of the cerebral cortex (region 6), and the corpus collosum at the level of the hippocampus (region 7) (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4 E and F). While vacuolation in the inferior cerebellar peduncle and spinal trigeminal tract (region 16) was relatively modest, lesions appeared earlier in this region and the degeneration was progressive.

Discussion

Initial behavioral tests of the Zurich Prnp0/0 mice, including swimming navigation, Y-Maze discrimination and the two-way avoidance shuttle box test, indicated that elimination of PrP expression did not compromise learning ability. Subsequent studies of learning and memory and associated hippocampal function using Prnp0/0 knockout mice have provided variable results [31-34]. Electrophysiological studies suggesting that GABAA receptor-mediated fast inhibition and long-term potentiation were impaired in hippocampal slices from Zurich Prnp0/0 mice [35, 36] were not independently confirmed [28, 37]. While progressive cognitive dysfunction is a feature of prion diseases in humans, physical problems such as ataxia, and changes in gait and posture are also typical characteristics. Therefore, in our behavioral assessments we used rotarod performance which requires postural adjustments for the maintenance of equilibrium on a rotating and accelerating rod. Rotarod performance is a commonly used task to assess motor coordination in genetically and pharmacologically modified mouse models and, while the ability to perform the rotarod task cannot be attributed to a single brain region, it has been shown to be a sensitive indicator of cerebellar abnormalities, for example in Lurcher mice [38]. While retinal degeneration in FVB mice caused by Pde6b gene mutations preclude tests of cognitive behavior that depend on vision, sight-impaired inbred mouse strains, including FVB, perform on the accelerating rotarod as well as strains that are not visually impaired, and FVB mice have been extensively used in rotarod studies [39, 40].

Cerebellar ataxia is an early symptom of GSS, preceding the onset of progressive dementia, and in some cases the clinical phase of disease may be as long as 10 years. The occurrence of sensorimotor deficits in Tg(GSS) mice similar to those observed in Prnp0/0 mice but considerably earlier than the onset of end-stage neurodegeneration, is consistent with a mechanism involving progressive loss of mutant PrPC function. In patients with inherited prion diseases such as GSS, loss of PrP function is presumably exacerbated at later times by the dominant-negative effects of mutant PrPSc. Indeed, our previous studies demonstrated that MoPrPSc-P101L accelerates prion disease in Tg(GSS) mice and that its accumulation is a late event in the course of disease [4]. Our studies suggest that the early behavioral abnormalities in Tg(GSS) mice serve as a preclinical predictor of prion disease that may be suitable for use in preclinical drug testing. Such approaches have been successfully applied using Tg models of Huntington’s disease (HD) [41, 42] which exhibit behavioral anomalies as early as 3 to 4 weeks of age.

Our results raise the question of why the neuropathological deficits reported here were not previously detected in Prnp0/0 mice. Seminal studies indicated coarse vacuolation in the Ammons horn of the hippocampus in about one third of Zurich Prnp0/0 or wild type mice analyzed [9]. Interestingly, histopathological analysis of older Zurich Prnp0/0 mice at 33 or 57 weeks post-inoculation with the Chandler prion isolate lacked vacuolation or gliosis in the molecular and pyramidal layers of the telencephalitic cortex or the ventromedial thalamic nucleus [7]. In other studies, scrapie-specific neuropathology was not detected in the brains of Prnp0/0 mice ~500 days post-inoculation with mouse adapted RML scrapie prions [43].

While the original Zurich strain of Prnp0/0 mice were maintained on a mixed 129/Sv and C57BL/6 genetic background, the Prnp0/0 mice used in these studies were derived by repeated crossing with wild-type FVB animals [28]. The resulting Prnp0/0 mice were used for the generation of Tg mice because of the large pronuclei and breeding performance of the FVB strain. In the current studies we compared mice expressing wild type and mutant Prnp alleles on syngeneic FVB/NJ (FVB) backgrounds. Our results raise the possibility that additional genetic factors may influence the development of spongiform degeneration; it may therefore be of considerable interest to assess the effect of the Prnp disruption in a variety different of inbred backgrounds. Interestingly, deficiencies in other genes, notably Mahogunin in Attractin (formerly mahogany) result in similar age-dependent spongiform neurodegeneration but without accumulation of PrPSc [44, 45]. Both mahoganoid and Atrn mutations affect coat color similar to Agouti. To explain the phenotypic overlap in Mahogunin and Attractin deficiencies, He and colleagues proposed a model in which neuronal accumulation of an unknown substrate(s) which is normally targeted for proteosomal degradation resulting from the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of Mahogunin, results in progressive vacuolation, astrocytosis, and neuronal cell death [45]. While PrP is not ubiquitinated by Mahogunin, our results raise the intriguing possibility that PrP, Atrn and Mahogunin function in the same pathway to preserve neuronal viability.

Fig. 5. Kinetics and regional distribution of spongiform degeneration in the brains of Tg(GSS)22 mice.

The extent of spongiform degeneration in the brains of spontaneously sick Tg(GSS)22 mice was determined in hematoxylin and eosin stained brain sections. For comparison, regions are shown where little or no spongiform pathology (A: cerebellum – region 14), or consistently high amounts of spongiform pathology (B: posterior midline cerebral cortex) was detected. In C, peroxidase immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the extent of reactive astrocytic gliosis in the posterior midline cerebral cortex region using antibodies to glial fibrillary acidic protein. D Neuronal vacuolation was quantified in 16 different brain regions of Tg(GSS)22 mice of different ages. Blue symbols: 6 months of age; black symbols: 5 months of age; magenta symbols: 4 months of age; green symbols: 3 months of age; red symbols: 2 months of age; orange symbols: 1 month of age.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the University of Kentucky Sanders Brown Center on Aging as well as grants from the U.S. Public Health Service RO1 NS/AI40334 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and N01-AI-25491 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lasmezas CI, Deslys JP, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin JM, Fournier JG, Hauw JJ, Rossier J, Dormont D. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science. 1997;275:402–405. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinge J, Palmer MS, Sidle KCL, Gowland I, Medori R, Ironside J, Lantos P. Transmission of fatal familial insomnia to laboratory animals (Lett.) Lancet. 1995;346:569–570. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medori R, Montagna P, Tritschler HJ, LeBlanc A, Cortelli P, Tinuper P, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P. Fatal familial insomnia: a second kindred with mutation of prion protein gene at codon 178. Neurology. 1992;42:669–670. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazor KE, Kuhn F, Seward T, Green M, Zwald D, Purro M, Schmid J, Biffiger K, Power AM, Oesch B, Raeber AJ, Telling GC. Immunodetection of disease-associated mutant PrP, which accelerates disease in GSS transgenic mice. Embo J. 2005;24:2472–2480. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Büeler H, Raeber A, Sailer A, Fischer M, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. High prion and PrPSc levels but delayed onset of disease in scrapie-inoculated mice heterozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Mol Med. 1994;1:19–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandner S, Isenmann S, Raeber A, Fischer M, Sailer A, Kobayashi Y, Marino S, Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Normal host prion protein necessary for scrapie-induced neurotoxicity. Nature. 1996;379:339–343. doi: 10.1038/379339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R-A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manson JC, Clarke AR, McBride PA, McConnell I, Hope J. PrP gene dosage determines the timing but not the final intensity or distribution of lesions in scrapie pathology. Neurodegeneration. 1994;3:331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büeler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H-P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356:577–582. doi: 10.1038/356577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, Hope J. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:121–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02780662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Nishida N, Moriuchi R, Shigematsu K, Sugimoto T, Nakatani A, Kataoka Y, Houtani T, Shirabe S, Okada H, Hasegawa S, Miyamoto T, Noda T. Loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in aged mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Nature. 1996;380:528–531. doi: 10.1038/380528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore RC, Lee IY, Silverman GL, Harrison PM, Strome R, Heinrich C, Karunaratne A, Pasternak SH, Chishti MA, Liang Y, Mastrangelo P, Wang K, Smit AFA, Katamine S, Carlson GA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Melton DW, Tremblay P, Hood LE, Westaway D. Ataxia in prion protein (PrP) deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:797–817. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi D, Cozzio A, Flechsig E, Klein MA, Rulicke T, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Onset of ataxia and Purkinje cell loss in PrP null mice inversely correlated with Dpl level in brain. Embo J. 2001;20:694–702. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobler I, Gaus SE, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rülicke T, Moser M, Oesch B, McBride PA, Manson JC. Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature. 1996;380:639–642. doi: 10.1038/380639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DR, Besinger A. Prion protein expression and superoxide dismutase activity. Biochem J. 1998;334:423–429. doi: 10.1042/bj3340423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown DR, Qin K, Herms JW, Madlung A, Manson J, Strome R, Fraser PE, Kruck T, von Bohlen A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Giese A, Westaway D, Kretzschmar H. The cellular prion protein binds copper in vivo. Nature. 1997;390:684–687. doi: 10.1038/37783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tremblay P, Meiner Z, Galou M, Heinrich C, Petromilli C, Lisse T, Cayetano J, Torchia M, Mobley W, Bujard H, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Doxycyline control of prion protein transgene expression modulates prion disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12580–12585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallucci GR, Ratte S, Asante EA, Linehan J, Gowland I, Jefferys JG, Collinge J. Post-natal knockout of prion protein alters hippocampal CA1 properties, but does not result in neurodegeneration. Embo J. 2002;21:202–210. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuwahara C, Takeuchi AM, Nishimura T, Haraguchi K, Kubosaki A, Matsumoto Y, Saeki K, Yokoyama T, Itohara S, Onodera T. Prions prevent neuronal cell-line death. Nature. 1999;400:225–226. doi: 10.1038/22241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DR, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. Prion protein-deficient cells show altered response to oxidative stress due to decreased SOD-1 activity. Exp Neurol. 1997;146:104–112. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bounhar Y, Zhang Y, Goodyer CG, LeBlanc A. Prion protein protects human neurons against Bax-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39145–39149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouillet-Richard S, Ermonval M, Chebassier C, Laplanche JL, Lehmann S, Launay JM, Kellermann O. Signal transduction through prion protein. Science. 2000;289:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. Embo J. 2002;21:3317–3326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chesebro B, Trifilo M, Race R, Meade-White K, Teng C, LaCasse R, Raymond L, Favara C, Baron G, Priola S, Caughey B, Masliah E, Oldstone M. Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie. Science. 2005;308:1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1110837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samaia HB, Brentani RR. Can loss-of-function prion-related diseases exist? Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:196–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsiao KK, Scott M, Foster D, Groth DF, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Spontaneous neurodegeneration in transgenic mice with mutant prion protein. Science. 1990;250:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1980379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telling GC, Haga T, Torchia M, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Interactions between wild-type and mutant prion proteins modulate neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lledo P-M, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Nicoll RA. Mice deficient for prion protein exhibit normal neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2403–2407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser H, Dickinson AG. The sequential development of the brain lesions of scrapie in three strains of mice. J Comp Pathol. 1968;78:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(68)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser H, Dickinson AG. Scrapie in mice. Agent-strain differences in the distribution and intensity of grey matter vacuolation. J Comp Pathol. 1973;83:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(73)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipp HP, Stagliar-Bozicevic M, Fischer M, Wolfer DP. A 2-year longitudinal study of swimming navigation in mice devoid of the prion protein: no evidence for neurological anomalies or spatial learning impairments. Behav Brain Res. 1998;95:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roesler R, Walz R, Quevedo J, de-Paris F, Zanata SM, Graner E, Izquierdo I, Martins VR, Brentani RR. Normal inhibitory avoidance learning and anxiety, but increased locomotor activity in mice devoid of PrP(C) Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;71:349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coitinho AS, Roesler R, Martins VR, Brentani RR, Izquierdo I. Cellular prion protein ablation impairs behavior as a function of age. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1375–1379. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000078541.07662.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Criado JR, Sanchez-Alavez M, Conti B, Giacchino JL, Wills DN, Henriksen SJ, Race R, Manson JC, Chesebro B, Oldstone MB. Mice devoid of prion protein have cognitive deficits that are rescued by reconstitution of PrP in neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collinge J, Whittington MA, Sidle KC, Smith CJ, Palmer MS, Clarke AR, Jefferys JGR. Prion protein is necessary for normal synaptic function. Nature. 1994;370:295–297. doi: 10.1038/370295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colling SB, Collinge J, Jefferys JGR. Hippocampal slices from prion protein null mice: disrupted Ca2+-activated K+ currents. Neurosci Lett. 1996;209:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12596-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herms JW, Kretzschmar HA, Titz S, Keller BU. Patch-clamp analysis of synaptic transmission to cerebellar purkinje cells of prion protein knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:2508–2512. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hilber P, Caston J. Motor skills and motor learning in Lurcher mutant mice during aging. Neuroscience. 2001;102:615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFadyen MP, Kusek G, Bolivar VJ, Flaherty L. Differences among eight inbred strains of mice in motor ability and motor learning on a rotorod. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:214–219. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadler JJ, Zou F, Huang H, Moy SS, Lauder J, Crawley JN, Threadgill DW, Wright FA, Magnuson TR. Large-scale gene expression differences across brain regions and inbred strains correlate with a behavioral phenotype. Genetics. 2006;174:1229–1236. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hickey MA, Gallant K, Gross GG, Levine MS, Chesselet MF. Early behavioral deficits in R6/2 mice suitable for use in preclinical drug testing. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schilling G, Coonfield ML, Ross CA, Borchelt DR. Coenzyme Q10 and remacemide hydrochloride ameliorate motor deficits in a Huntington’s disease transgenic mouse model. Neurosci Lett. 2001;315:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prusiner SB, Groth D, Serban A, Koehler R, Foster D, Torchia M, Burton D, Yang S-L, DeArmond SJ. Ablation of the prion protein (PrP) gene in mice prevents scrapie and facilitates production of anti-PrP antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10608–10612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bronson RT, Donahue LR, Samples R, Kim JH, Naggert JK. Mice with mutations in the mahogany gene Atrn have cerebral spongiform changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:724–730. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.7.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He L, Lu XY, Jolly AF, Eldridge AG, Watson SJ, Jackson PK, Barsh GS, Gunn TM. Spongiform degeneration in mahoganoid mutant mice. Science. 2003;299:710–712. doi: 10.1126/science.1079694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen G, La Porte N, Diechtiaref fB, Pung C, Nissanov J, Gustafson C, Bertrand L, Gefen S, Fan Y, Tretiak O, Manly K, Park M, Williams A, Connolly M, Capra J, Williams R. Informatics center for mouse genomics: the dissection of complex traits of the nervous system. Neuroinformatics. 2003;1:327–342. doi: 10.1385/NI:1:4:327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]